1. Introduction

This paper is concerned with Regional Organisations (ROs) which may be defined in terms of the degree of integration and cooperation among governments or non-governmental institutions in three or more geographically proximate and interdependent countries for the mutual gain of its membership in one or more issue-areas. Regional integration is largely dependent on the ability of an RO to broker and forge convergence among its agent member states [

1], and for Kelly [

2] this hinges on the degree of heterogeneity in its population of actors. It also depends on cooperation [

3], this being a function of strategic substructural regulations from which arise the structural rules that agents should abide by and the consequential behaviours that arise, and which can, in turn, shape the development of regional integration. The primary purpose of this paper is to explore RO efficacy in mission servicing, where a mission is an expression of its purpose and aspiration. This involves an appreciation of the RO social organisation and the substructural attributes that form it. Firth ([

4]: 1) explains that social organisation is a dynamic concept with both a narrow and broad context: “In a narrow context, organisation implies a systematic ordering of positions and duties which defines a chain of command and makes possible the administrative integration of specialized functions towards a recognized limited goal. In a broader context, it implies a diversity of the ends and activities of individuals in society, a pattern for their co-ordination in some particular sphere, and specific integration of them there by processes of choice and decision into a coherent system, to yield some envisaged result. It can be phrased again as that continuous set of operations in a field of social action which conduces to the control and combination of elements of action into a system by choice and limitation of their relations to any given ends.” The substructure is responsible for the pattern that develops.

Satisfying the primary purpose requires a secondary purpose, which is to explore ROs pragmatically, this calling on a case study approach, which is “particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context” ([

5]: 1), where theory and any capacity for mensuration underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies. The case we shall adopt is that of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). To obtain an initial sense of an RO, it is always useful to look at its mission. The mission of ASEAN is to maintain political security in its community, and to provide for its well-integrated economics and a socioculture that enhances the quality of life among the citizens of its member states [

6]. These are underpinned by its values, which may be identified as “respect, peace and security, prosperity, non-interference, consultation/dialogue, adherence to international law and rules of trade, democracy, freedom, promotion and protection [of dignity and equality as] human rights, unity in diversity, inclusivity, and ASEAN centrality in conducting external relations” ([

7]: 1). How these values are manifested strategically and behaviourally is at least reflected in RO social organisational differences.

Any study of ROs is essentially problematic because according to de Lombaerde et al. ([

8]: 731) “there is virtually no systematic debate on the fundamentals of comparative research in the study of international regionalism. The field of research is very fragmented and there is a lack of communication between scholars from various theoretical standpoints and research traditions. Related to these two divides is the tension between idiographic and nomothetic methodology.” Ideographic methodology relates to the study of a group entity with specific individualistic properties, while the nomothetic form relates to the generalised properties of a given context. This tension can be responded to using systems and indeed cybernetic modelling, which is capable of systematically organising effective ways of modelling organisations and their contexts while understanding the impact of reflexive processes, and enabling specific cases to be visited.

ASEAN is interested in developing friendly relations and mutually beneficial dialogues, cooperation and partnerships with countries and sub-regional, regional and international organisations and institutions [

9]. Understanding the consequences of this positioning for the RO in terms of its social organisation, policies, and the potential it has for coherent policy and its implementation, is important if one is to create future expectations about its behaviour in varying contexts. To achieve this, connecting relevant cross-disciplinary theories in the analysis of ROs can help to better understand and improve the capacity and quality of cooperation among member states, and this is central to RO mission and aims. This is because it can help to address different aspects of multifaceted complex phenomena that affect ROs by introducing different related perspectives. The complexity of RO processes for the purposes of analysis is recognised when one considers that they are not simple or static entities, but rather complex and dynamic systems that interact with multiple and changing environments. A cross-disciplinary approach can help to challenge and improve existing theories that are disciplinary or conventional, by offering complementary propositions that add dimensionality. Theory cross-disciplinarity can occur through configurative processes, involving the interconnection of models through patterns or arrangements of elements or components to form a greater model. Configurations have inherent coordinative structures that can respond to the needs of complexity modelling by incorporating connecting schemas representing processes of change [

10]. Core to RO development is the issue of cooperation. This complex phenomenon can be influenced by various factors such as social relationships, cognitive styles, values, behaviours, mindsets, agencies and pathologies. By configuring insights from relevant theories in say sociology, cultural anthropology and social psychology, one can provide improved explanations on how, for instance, motivations, incentives, expectations and outcomes of cooperation occur in different ROs.

The issue of ROs diversity also enters into any analysis of these organisation, especially where they are composed of heterogeneous and diverse member states that have overlapping and not necessarily synergistic goals and logic. This diversity can be described in a western context as a “spaghetti bowl’ [

11,

12], or in an Asian context as a “noodle bowl” [

13,

14]. That there is such complexity delivers a realisation of the need for regional integration, this helping agency to overcome the agent divisions that impede the flow of goods, services, capital, people and ideas, the divisions constraining economic growth [

15]. ROs may be seen to be successful when they can generate and engage in multinational arrangements. These may be coordinated, but where they are not, a growing repertoire of non-coordinated multilateral agreements can negatively impact regional integration by creating geopolitical tensions that have the potential to distort trading incentives [

16]. This reflects on the capacity of ROs to adequately cooperate, and this in turn impacts on their capacity to efficaciously generate collective actions. It also refers to any action that an agent engages in on behalf of its agency to achieve group goals [

17], though this may arise from different orientations in social organisation. RO agent cooperation is often motivated by national self-interest and viewed as a necessary vehicle to resolve common problems and pursue complementary interests. However, degrees of cooperation may vary with different agencies.

To explore ROs, we use metacybernetic models that see ROs as complex adaptive systems. This combines a realist ontology (the assumption that there is a reality independent of our perception) with a relativist epistemology (the assumption that our knowledge of reality is socially constructed and fallible). It is concerned with complex dynamic phenomena that have multiple layers of meaning and hidden causation. The approach it adopts goes beyond observable phenomena, seeking to identify a substructural model that will create structural and behavioural imperatives. It is a retroductive approach to inquiry that connects empirical observations with causative propositional explanations, creating an a-priori approach. It is also a cybernetic approach that recognise ROs as complex adaptive systems that can help understand and predict the dynamic behaviour of those systems that are otherwise difficult to model with more traditional approaches. It provides a way of thinking about and analysing complex situations by recognising their complexity and their patterns and interrelationships, rather than only examining their cause and effect [

18].

Complex adaptive systems thinking suggests that in any agency, the agents in its population are components of that system, and they interact with each other in ways that are globally (with respect to the agency) unpredictable and unplanned, while the rationality of those interactions is a local function of the interactive agents. When a complex adaptive system is expressed in terms of autopoiesis (the self-production of elements of itself deemed to be requisite for adaptive processes), it may also be referred to as a generic living system. This provides a rationale for our choice of modelling ROs through Cultural Agency Theory (CAT). This is a complex adaptive system modelling approach which derives from metacybernetic theory [

19], a reflexive schema that can provide greater insights into the development potential and pathologies of ROs like ASEAN. While some studies of intergovernmental alliances offer behavioural analyses that consider only tangible variables (those that can be directly measured), CAT provides an analytical approach that can explore both tangible and intangible variables to explain their differences. The tangible variables emanate from a behavioural system that operates as the organisational residence of a population of related agents, and the action that results occurs as mutual interaction. The intangible variables emanate from a substructure that cannot be directly measured. CAT has, as part of its structure, autonomous and adaptive and mutually interactive formative traits that determine agency character. It has two modelling derivatives. One of these is Multiple Identity Theory (MIT), from which one may see identity as an emergent phenomenon resulting from the interactions occurring between agency traits. The usual horizontal model of MIT considers how identity changes with context. The less considered vertical model involves classes of identity that are ontologically distinguished in a functional hierarchy, and there is a correlation between identity pathologies and schisms that occur between the ontological components. The other modelling derivative is Mindset Agency Theory (MAT), formulated as a methodology by Yolles and Fink [

10], from which qualitative and qualitative empirical methods are possible, and which we will here qualitatively apply to ASEAN.

This paper is set up in two parts: part one is theoretical, extending the configurations of metacybernetics to enable improved analysis of ROs; and part two which applies the theory to ASEAN, selected due to the inherent paradoxes that plague its operations. The two-part paper should be seen as a development of Rautakivi and Yolles [

20]. The structure of this part one is as follows. In

Section 2 we introduce metacybernetics and develop it further by reconfiguring it to include Tönnies social organisation approach that considers, in the context here, sociopolitical relationships. In

Section 3 we discuss our considerations and provide a conclusion.

2. Modelling Regional Organisations with Metacybernetics

According to Yang and Cormican [

21], problems can arise in organisations like lack of integration, this having an impact on communication and fragmenting responses in relation to known issues. This can be overcome by untangling the complexity of organisational processes and interactions through theories of complex adaptive systems. Now, ROs may be seen as complex adaptive agencies that are defined by a community of agents that necessarily interact. This realisation is consistent with theory applied to communities, as noted by Luloff and Bridger [

22]. They note that agents behave and act purposively in response to the concept they have and in their connections with others. From this start, they are led to a discussion of the use of Tönnies sociological model of social organisation that has been applied in the study of communities. However, ROs are both communities and complex adaptive agencies, and so it is appropriate to adopt an appropriate theory, and preferably one that involves configurations, to model them.

Metacybernetics is built on principles provided by Eric Schwarz [

23] for complex adaptive systems, but is designed as configurative framework [

10]. Its Cultural Agency Theory(CAT) derivative is a cybernetic model based on the idea that culture is a system of shared meanings that agents use to interpret and make sense of their environment, and postulates that the nature of an agency is determined by a set of formative traits. In order to satisfy the complexity needs of ROs, it will be developed through configuration connecting three dichotomous paradigms: the Tönnies sociological paradigm of social organisation (with values of Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft); the psychology cognitive style paradigm of Witkins et al. and Shotwell et al. (with values of Patternism and Dramatism); and the Triandis social psychology paradigm of connective disposition (with values of Collectivism and Individualism). If identity is considered to emerge from the interaction of the CAT formative traits, the values they take defining character, then the interactive combinations will enable different identities to emerge under the influence of changing contexts. Multiple Identity Theory (MIT) provides a nuanced view of identity and its nature, recognising that agencies create and maintain context-sensitive horizontal and vertical variations in identity. Horizontal variations allow for different identities to be manifested under different contextual conditions. Vertical variations are concerned with the internal consistency of agency identity. Mindset Agency Theory (MAT) is a direct development from CAT, and offers a capacity for empirical inquiry. It is a psychology model that is based on the idea that agencies have different mindsets or ways of thinking about their environment. It is also concerned with how these mindsets influence agent behaviour and decision-making processes.

In this section we shall explore these paradigms and establish a suitable configuration for them. It will be seen that CAT offers a general reflexive model able to investigate complex organisations. This vertical model has some connection with Carl Jung’s theory of Individuation in which the psyche is seen as a self-regulating system that seeks to maintain a balance between opposing qualities [

24,

25]. MIT explains how identity reflexively and interactively connects with CAT traits, and where any identity schisms experienced have reflections in relevant trait relationships. These reflections will be important for trait theory development relating to agency stability and coherence, and also for pragmatic purposes when ASEAN is later explored. Finally, Mindset Agency Theory (MAT) will be used to identify and illustrate how traits, and thus mindsets, can be qualitatively measured. The new theory that develops will be shown to quite simply indicate stability/coherence or instability/incoherence in complex adaptive agencies like ROs.

2.1. The Social Organisation Paradigm

Tönnies [

26] was interested in providing a way by which social organisation could be understood, this being based on the dichotomous concept of social action and agency behaviour as expressed through the notions of Gemeinschaft (community service) and Gesellschaft (company service) [

27]. Here, we shall consider this paradigm, and explore how it may be related to collective action.

Gemeinschaft is a structural condition of community that is enabled by norms, values and beliefs, while Gesellschaft is rather a condition that relates to society in which structural relationships are driven by self-interest as a primary justification. This distinction directs the actions of social agents. Social agents, in this theory, can be individuals, communities, societies, or a state or region. While Gemeinschaft creates a location for productive work, Gesellschaft does not produce any utilities at all [

28].

Gemeinschaft arises structurally when there are shared values and collective goals, and involves the subjective experience of group membership—an enduring, trans-situational affective attachment that binds people to groups [

29,

30,

31]. It includes a sense of collective self-identity [

32] and perceptions and feelings of social solidarity [

33]. For Willer [

34], it is an identification with the group. It also involves strong altruistic feelings, illustrated for instance by the idea of the spirit of public goods [

35].

Gesellschaft arises structurally through values that are based on rationality, and hence goal rationality is the dominant attribute and means by which certain goals can be achieved; it is also instrumental and calculating [

35]. More, a characteristic of the Gesellschaft perspective is that the world should be left unchanged and unimproved. This perspective shares similar characteristics to the idea of harmony, where the world should be understood and appreciated rather than exploited. Gesellschaft decisions are based on instrumental (i.e., goal-directed) and (optimal) economical calculations, and it is blind to feelings of security, trust and intimacy between members of a community ([

35]:6). Associates are defined in terms of objectives rather than in inter-agent relationships, and sensitive to time, location and situation [

28].

Following Rodriguez [

36], Gemeinschaft is driven by natural and spontaneously arising emotions and expressions of sentiment (

Wesenwille, or natural will). However, Gesellschaft is connected with bureaucratic processes, and with rational self-interest and calculating conduct act that weakens the traditional bonds of family, kinship, and religion (

Kürwille, or rational will). Gesellschaft operates within the Gemeinschaft structure, and when connected with human relations is more impersonal and indirect, where rationally is constructed in the interest of efficiency or other economic and political considerations.

Thus, in large agency contexts, agents have neither pure Gemeinschaft nor Gesellschaft structural relationships. This varies in a way that depends on the characteristics that dominate the organisation. The paradigm as constructed in the 1880s was relevant to a European social structure in which there was a different dominating culture. In those days, social and economic inequality was normal, and not something to be overcome. Tönnies argued that members of the society obtain status by birth (Gemeinschaft), and 19 century Europe was an unequal class society. A Gesellschaft orientation indicates that membership in a society is determined by status, education and work. This is not so relevant to the current situation in Asia, where societies embrace class and hierarchy, and where social status depends on birth and family. In other words, the Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft paradigm is Western-centric.

2.2. The Tönnies-Triandis Connection

The Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft paradigm of Tönnies looks at the social organisation in terms of intangibles conditions that reflect on agent behaviour and social action, linking to other intangibles like values. Triandis [

37] rather came to a similar consideration from the connective disposition paradigm intangibilities, and this has consequences for both social organisation and agent behaviour. These are dichotomous values that can be used to describe differences in behaviour. The variable of connective disposition corresponds to the degree to which agencies identify with self rather than society. Collectivists view themselves primarily as parts of a whole and tend to be motivated by the norms and duties imposed by the collective. Individualists, on the other hand, view themselves as independent entities that are primarily motivated by their own goals and desires. Triandis came to his paradigm from a detailed examination of Hofstede’s [

38] propositions concerning the cultural dimensions of cross-cultural communication. Like the Tönnies paradigm, that of Triandis has had significant interest over the last two generations [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. This is illustrated by its manifestation in other fields of study, for instance in economics which adopts the terms ‘Methodological Individualism’ versus ‘Methodological Institutionalism’ [

46], and in politics with ‘Transactional Individualism’ versus ‘Relational Collectivism’ [

47]. However, Schwartz ([

48]: 139) noted three criticisms of the connective disposition paradigm due to its over-generality: “The dichotomy leads one to overlook values that inherently serve both individual and collective interests (e.g., wisdom), it ignores values that foster the goals of collectivities other than the ingroup (e.g., universal values like social justice), and it promotes the mistaken assumption that Individualistic and Collectivistic values each form coherent syndromes that are in polar opposition.” In his research involving a more fine-tuned analysis of ten types of values he postulated to be present in all cultures [

49], analysis from extensive empirical studies revealed meaningful group differences that are obscured by the connective disposition dichotomous values of Individualism-Collectivism. He, therefore, developed what he considered to be an alternative value system theory that was devoid of the concept of “connective disposition. As if in a full circle, however, his theory has been returned include connective disposition paradigm by Yolles and Fink [

50]. This Mindset Agency Theory arises through configurations that include Schwartz’s value system theory [

51], set within the context of Maruyama’s [

52] Mindscape theory. From these beginnings, a set of cognitive traits were formulated that coalesce into a variety of mindsets, neatly falling into a variety of Collectivistic and Individualistic categories. The construct enables that, for a given agency, the Tönnies paradigm can be shown to be ontologically distinguishable from the Triandis paradigm. Epistemologically, the two paradigms operate with relatable knowing about values and structural relationships in social organisations, but they are ontologically distinct. It also includes the concept of the normative personality, which is the collective personality that emerges from the interactions of the agents of an agency. This is slightly different from the more common psychology idea of the term, which refers to changes in agent personality over its lifespan.

Neff [

53] examines the relationship between the connective disposition paradigm involving Collectivism-Individualism, and explains that it strongly echoes the social organisation paradigm of Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft. A Gemeinschaft agency operates through collective structural relationships with collective goals and understandings, and its agents are connected with shared customs and traditions. Gesellschaft agencies are associated with explicit contracts and pursue rational self-interest that overrides any concern they may have with others. Individualist agencies have weak group boundaries and reduced constraints on individual activities and are characterised as having an autonomous view of life, adopting abstract principles of morality, and seeing themselves as independent, competitive, creative, and self-reliant, with personal goals placed ahead of group goals. Greenfield [

45] is consistent in this by noting that sociocultural environments are not static either in the developed or the developing world and should be considered to involve dynamic processes. Agencies can adapt to changing situations. Through their adaptive processes, social variables may shift between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. These are coherent with cognitive shifts of connective disposition towards either Collectivism or Individualism.

Connective disposition creates social adaptative imperatives for social orientation. Independence and interdependence are more psychological variations of the same concepts. In Collectivism, sharing occurs among agents and is adapted to the daily practices that occur in Gemeinschaft environments like

sharing a social good. Individualistic values like privacy are adapted to the characteristics of Gesellschaft environments like

distinguishing attributes of social good. However, the terms Collectivism and Individualism are not adequate to describe cognitive adaptation in the two classes of the social environment. Connective disposition summarises social adaptations as two types of the environment, Collectivism with interdependence and Individualism with independence. However, due to their cultural values origin, they do not immediately explain causal behaviour [

54]. Connecting with other value theories, like that of the sociocultural dynamics of Sorokin [

55], both the Tönnies and Triandis paradigms can be elaborated on through configuration processes [

10].

The connective disposition paradigm represents is indicative of agency attitude, this created through manifestation of values collected in one or the other of the dichotomous options [

56,

57]. To illustrate this, agencies with Collectivist attitudes have firm group boundaries with strong collective constraints on individual activities. Such agencies have a connected view of self (being socio-centric), placing value on attachment and interdependence, with the moral world seen in terms of interpersonal responsibilities of care and duty. While the Tönnies paradigm has been usefully applied to agencies in the past, the developments that have occurred in the Triandis paradigm make it more suitable for the analysis of ROs.

Essentially, Collectivism when influencing social orientation promotes the well-being of the agency as a collective, whereas Individualism is rather directed toward the well-being of its agents as individuals. Collectivism ideally relates to people coming together in a collective to act unitarily through normative processes to satisfy some commonly agreed and understood purpose or interest [

58]. In contrast, Individualism is the doctrine that all social phenomena, including their structure and potential towards change, are in principle explicable only in terms of agents and, for instance, their properties, goals, and beliefs. Agencies that are either Collectivistic or Individualistic have realities that are differently framed. They, therefore, maintain ontological distinctions the boundaries of which determine their frames of reality and influence the capacity of agencies for coherent and meaningful communications.

2.3. The CAT Model of Metacybernetics

Beer [

59] studied the relationship between the system and metasystem, arguing for a 2nd order cybernetic model in which the system that delivers behaviour is cognitively informed by its hierarchically related metasystem. This connection between the system and metasystem is logically closed, so that its processes are driven by internal contexts, not environmental ones which can only stimulate it. Schwarz [

23] developed a 3rd order model representative of living systems in which the derivation of metasystem processes starts to become transparent. As a living system theory, it involves processes of autopoiesis [

60] and its higher-order form called autogenesis. Autopoiesis is a network of processes that satisfies the strategic needs of a system and operates as a process of intelligence autogenesis (or self-creation). Autogenesis, as a higher-order strategic process, stabilises autopoietic processes. Yolles [

61] has connected these networks of processes with Piaget’s [

62] notions of operative and figurative intelligence, and incidentally sets the scene to demonstrate that ROs can be characterised in terms of a normative personality. Operative intelligence is taken as the active aspect of intelligence, involving all actions, overt or covert, undertaken to enable an agency to follow, recover, or anticipate the transformations of effects that are of interest. Figurative intelligence is a more or less static aspect of intelligence and involves the means of representation used to retain transformational states of mind. However, if figurative intelligence is seen to have a reflexive relationship with operative intelligence, that the former relative to the latter has its own activity role. Thus, autopoiesis enables the system to self-produce those strategic processes required for its self-maintenance and to adapt to changing environmental contexts. Understanding derives from operative intelligence, and its medial figurative intelligence is dependent on operative intelligence to derive meaning, since cognitive states do not exist independently of the adaptive transformations that interconnect them.

In the theory of autonomous complex adaptive systems theory developed by Schwarz [

23], autopoiesis (or rather operative intelligence) is essential to the viability of a system since it enables it to “digest” any unexpected fluctuation. It does this through what he calls entropic drift to regenerate the system’s structure, and through autopoiesis by modifying structural form and the behaviour of the organisation. The higher-order intelligence of autogenesis (or figurative intelligence as a reflexive to operative intelligence) acts to stabilise the relationship between the metasystem and the structural operative system.

We can focus on an RO as being an agency with an operative system composed of a population of agents each with their own operative system, and each an independent member state, the agents being in mutual interaction. From a cybernetic perspective, the relationship between a set of interactive systemic objects can be explored through purpose, teleology, control and feedback ([

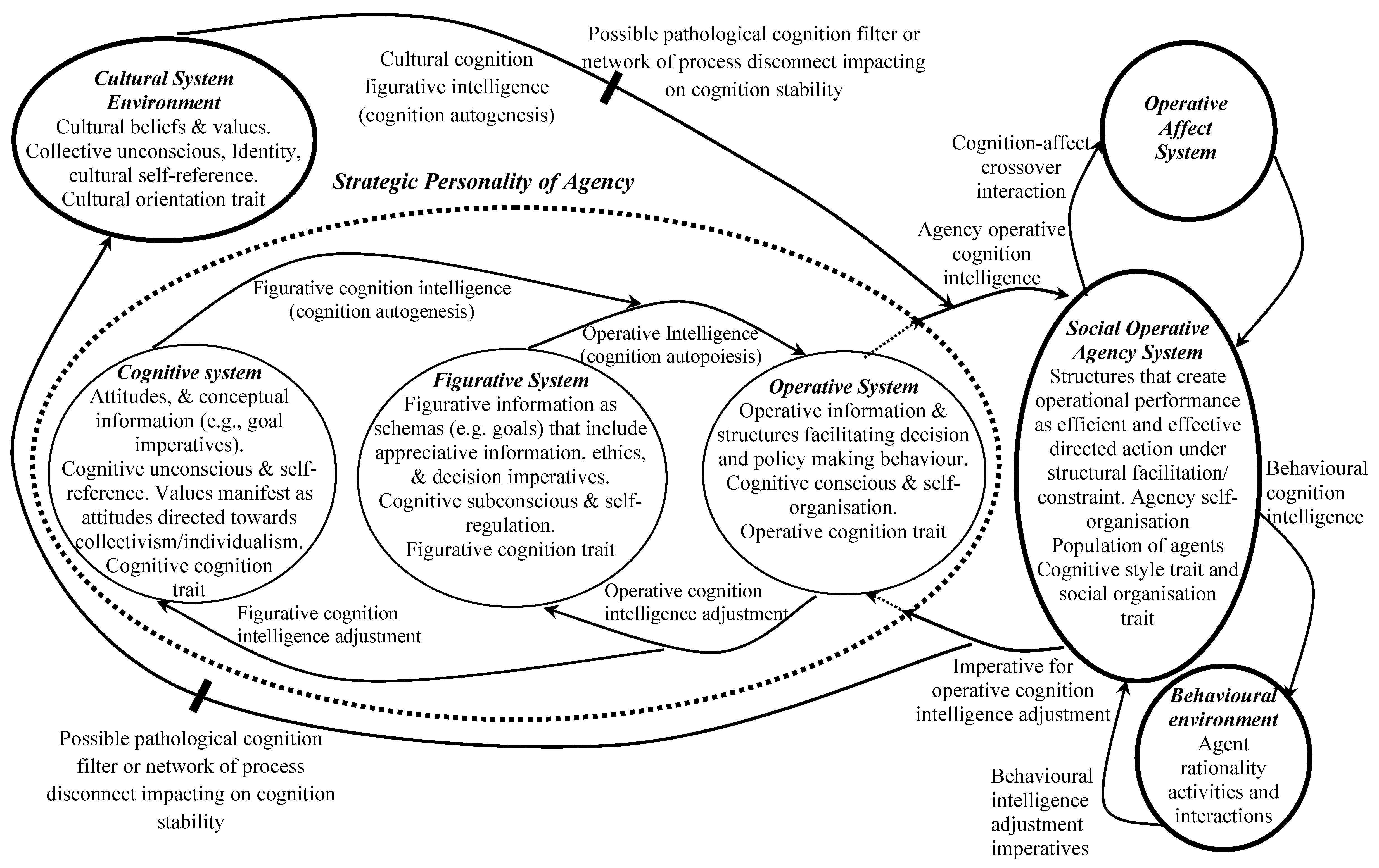

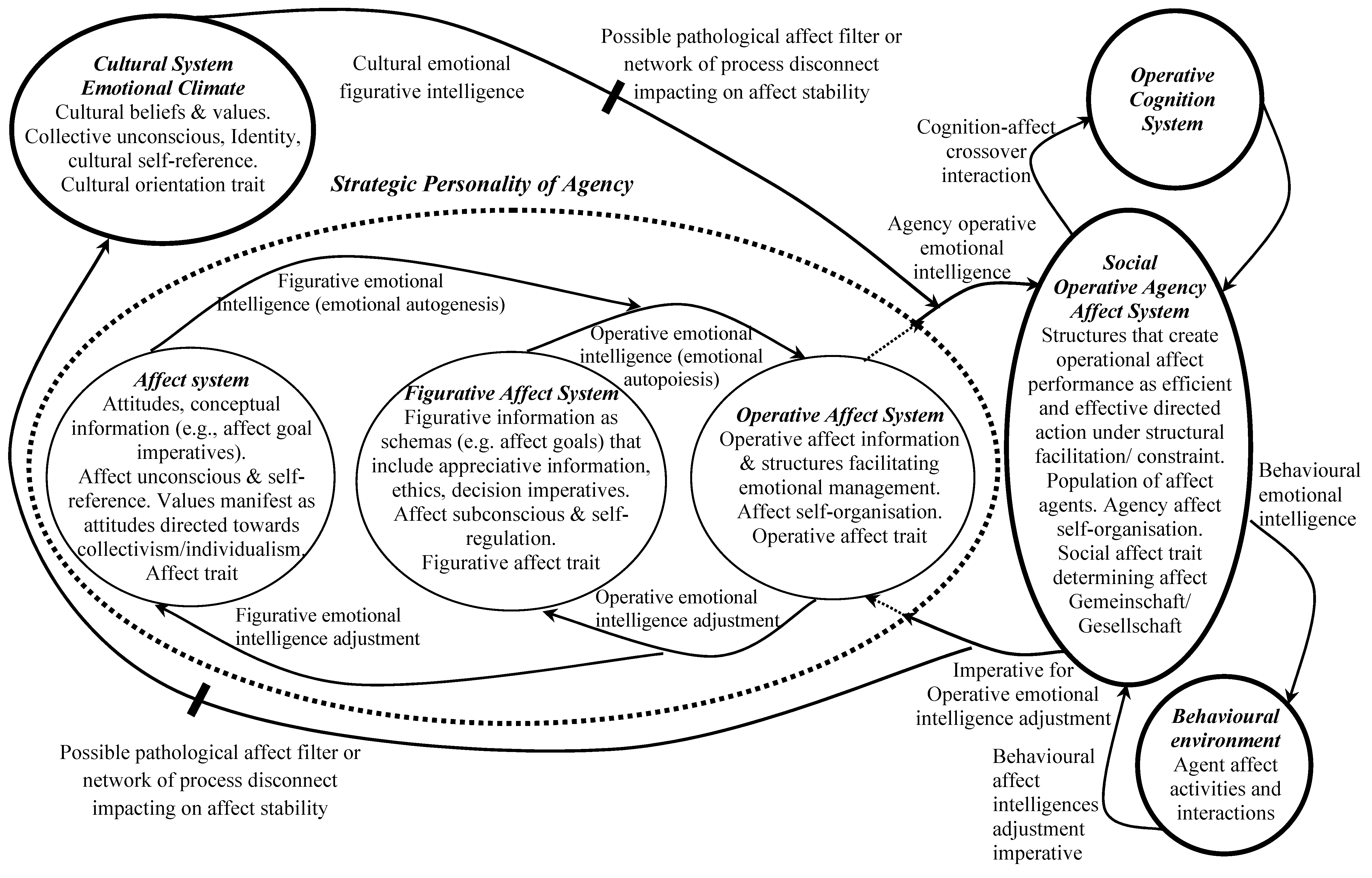

63]: 4). A model that satisfies this can be represented through a third-order cybernetic model of CAT. In

Figure 1 this is represented as a cognition processes and

Figure 2 as an affect processes. Lateral reflexive crossover between cognition and affect occurs through the operative system so cognition is influenced by affect, and vice versa [

19]. The feedback processes enable the present state of a system to be seen as a function of its preceding states so that the future is always a result of the past. Feedback systems may be susceptible to pathologies that inhibit two-way communications between agents that do not allow for responsive behaviours to a given set of actions. Pathologies may also occur within agency, for instance through a pathological filter or a network of processes disconnect in the intelligences, such a situation being indicated in both

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 concerning figurative intelligence. A disconnect here means that the RO functions instrumentally, responding to situations according to its existing repertoire of strategies, and unable to either learn or apply what it has learned.

Agency refers to autonomous social human groups. Autonomy creates organisational capabilities, procedures and implementation of policy without pressure or interest from social forces or social groups [

64] and provides a platform for critical thinking. Cerinšek and Dolinsek [

65] notes that autonomy and thinking critically are also relevant for innovation. These can be modelled as systems that are “self-organising, proactive, self-regulating, and self-reflecting, and they are participative in creating their own behaviour and contributors to their life circumstances linked to information processes with both the self-efficacy (the belief one has about one’s efficacy) of an agency and its ‘collective efficacy’ (the collective belief about its efficacy). Efficacy is conditioned by emotive imperatives (deriving from emotions and feelings) that can be controlled [

66] by emotional intelligence [

67].

The autopoietic nature of an agency provides it with the capability of producing for itself essential aspects of itself that enables it to self-maintain and adapt by producing a self-image and its future as a pattern of behaviour. Beer ([

59]: 408-412) highlights a particular issue that sometimes arises for agencies, called pathological autopoiesis. To understand this, consider that its strategic personality is responsible for its regulatory processes, and these are invoked to enable it to control itself such that its purposes can be achieved behaviourally. However, pathologies might arise when its regulative capacity is repurposed as a thing in itself, so that agency strategic purpose becomes subsumed to the function of control itself, and is a possible indicator of (pathological) narcissistic personality disorder [

68,

69]. So, pathological autopoiesis is a condition in which agency becomes locked into its image so that operative intelligence inputs from its environment are pathological. Following Yolles [

70], this leads agency to a stationary image of itself and its future. It may adapt, but if none of the possibilities available within that image is adequate to deal with the changing environment, then its capacity for adaptation is bounded by its stationarity. In general, while it might appear that an evolutionary process is underway, this is not the case since a host of variations available to its environment will be called on, but no new evolutionary ones will develop. As a consequence, there is no possibility for a co-evolutionary process.

2.4. The Intelligences

Operative intelligence is, in essence, a network of processes that arises from Piaget [

62] and is not a theory of general intelligence [

71,

72] the nature of which is different. Intelligence is the ability to understand and realize one’s knowledge of the environment to construct new knowledge and convert information about its experiences and past, and thus pursue its goals. Intelligences enable the consideration of interests and influences of the external environment, an agency’s own goals, the goals of others, and facilitation of the development of ideas about the possible reactions of others concerning the action taken by the agency [

73]. intelligence is the capacity of an agent to discover its own knowledge and information about its environment, to construct new knowledge converted from information and experiences from the past, and to pursue its goals effectively and efficiently; all of which are terms associated with the concept of efficacy.

For any system or organisation to be efficacious and viable, it needs a meta-system, which defines the relationship between the operative system and figurative system. The metasystem includes executive and control systems, which interact between operative systems which represent an organisation’s operations, management and process. It is also the simplest model of a living system following Maturana and Varela [

60]. The core idea of the relationship between the two traits is autopoiesis, mediated by system controls.

The operative system needs operative intelligence which can be explained in the following way: operative intelligence (often referred to as autopoiesis) is a network of processes capable of agency self-production, defines a living system and creates an operative couple between the figurative and operative systems [

23,

74]. As a living system, it regenerates its operational codes, implements its system requirements, and follows its own laws and regulations. Operative intelligence is a term coined by Piaget [

62] and is representable as a form of autopoiesis, defined here as a network of processes that can manifest information between trait systems. Following both Piaget and Bandura [

75,

76], operative intelligence may be taken to have an efficacious capacity in an agency to create a cycle of activity that manifests figurative objects as operative objects, hence operative intelligence provides for a capacity to evidence its figurative attributes. A summary of the different intelligences can be given as follows (adapted from Yolles [

77]):

Behavioural intelligence connects environmental parameters with the operative system. Its action enables the contextual and perhaps dynamic parameters in the environment to be identified, selected and measured. The intelligence structures the data used as a data model used for operations. The intelligence works in two directions, towards the environment where it informs agent behaviour, and towards the operative system where structured data can be updated.

Operative intelligence enables autopoiesis (self-production through its network of processes) that connects the operative and figurative systems, wh [

67]ere autopoiesis services the processes of agency self-regulation. Structural information is acquired from the structure data deriving from the environment, and this is transformed autopoietically so that it can be referred to by the figurative system. Autopoietic circular causality occurs when the regulatory map is updated enabling new regulatory processes to arise, and an alternative flow can adjust the structured data model.

Figurative intelligence enables autogenesis (self-creation). It acquires information from parameters in the agency personality, and it determines if there are any indications of instability in that personality. Where there are, it determines the causes and takes self-stabilising control action to correct this. The reverse action also occurs to enable adjustments.

We are aware that the intelligences can refer to cognition or affect. Cognition intelligence is part of the cognition system from which rationality emanates, and it is responsible through its network of processes for efficacious action [

77]. The second is affect/emotional intelligence which is responsible for controlling and manifesting emotion, as well as recognising it in a social setting. The notion of emotional intelligence arises from Salovey and Mayer ([

67]: 185), who define it as a “set of skills that contribute to the accurate appraisal and expression of emotion in oneself and others, the effective regulation of emotion in self and others, and the use of feelings to motivate, plan, and achieve in one’s life.” Cognition and affect forms of intelligence are independent, but they are also mutually responsive to influences that occur through cognition and affect crossover interaction.

2.5. Agency and Multiple Identity Theory

Agency is a sociopolitical entity with a mindset that is influenced by its formative traits that determine its character and patterns of behaviour. The interaction between the traits is a complex process from which one envisages there emerges the agency’s identity, this giving it a sense of self and purpose. Agency is the capacity of an actor to act in a given environment to use its power and autonomy on its relationships and the sociopolitical and other forces that it recognises, which can limit or facilitate options for behaviour. Its identity refers to the distinctive qualities or traits that make an agency unique, and it is associated with the concept of self, and with self-image and self-esteem. Identity is seen differently in different disciplines. Thus, “a brief summary of sociological theories concerning the development of identity states that it emerges through the interactions between individuals and society, implying that the individual is unable to attain an identity in an autonomous manner” [

78]. This sociological view focuses on society’s impact on the self. In contrast, the view from psychology focuses on an individual’s sense of self, noting external influences. Such a view would deny that “agency is unable to attain an identity in an autonomous manner,” and would rather hold that both autonomous processes and environment are important.

Multiple identity theory comes out of the discipline of psychology with two conceptual prongs. One takes a horizonal perspective that recognises that agencies can have different identities that are activated in different contexts and situations [

79]. The other takes a vertical perspective that there are levels of identity, and that the levels are arranged in ontological hierarchies [

80]. It suggests that identities are real entities that belong to different levels of being or reality, and that the hierarchy of identity salience (or prominence) corresponds to the hierarchy of ontological priority [

79]. While the horizontal perspective is taken as given, our interest here lies in the vertical perspective.

From a complexity perspective, let us propose that agency is psychologically composed of autonomous and adaptive formative traits that interact, and from these interactions there emerges properties of identity. The traits and that which emerges co-evolve, and interact through reflexive processes. The reflexivity enables the emergent phenomena to constrain and facilitate trait behaviour which can in turn adjust and sustain the emergent phenomenon.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 can then be considered in different terms, as an ontological hierarchy of emergent identities. Internal agency identity conflicts can then have an autopoietic explanation, and provide illustration of how such conflicts can be represented as behavioural pathologies, a theory adopted by Yolles and Fink [

10], where they distinguish between three ontologically distinct levels:

Private identity is agency’s primary identity in that it constitutes a mind that reflects personal values, beliefs, goals, and motivations and influenced by emotions, memories, and experiences. This identity is not usually shared with others, unless there is a high level of trust and intimacy.

Personal identity is agency’s secondary identity that an agency displays to others in interpersonal interactions, which reflects their self-image, self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-expression. It is influenced by its personality and knowledge. This identity may vary depending on the context and the audience, but it is generally consistent with private identity.

Public identity is agency’s tertiary identity that an agent has in relation to a larger social environment, and reflects social roles, norms, expectations, and obligations. It is influenced by cultural factors and other social categories. This identity may be imposed or chosen by the agency, but it is usually visible and recognisable by others.

That identity emerges from trait interactions recognises that there is a distinction between identity and mindset traits. This distinction is shown using the Hijman [

81] Dynamic Identity Model related to media-image, which explains identity as the link between the personal/psychological and the social/cultural, and results in the illustration that there are connections between agency personality/sociocultural mindset traits [

10]. This is also supported by Kaplan and Garner [

82] who independently explain that personal identity is a complex dynamic system that is mediated by, among other things, implicit dispositions, where dispositions are indicative of mindset traits. They also note that identity (like mindset) is not static, but changes over time and with context. Thus, identity and mindset traits are integrally related, enabling us to propose a relationship between personal identity and personality mindset. Personality mindset traits affect personal identity by shaping how agency relates to others and to itself. Personal identity affect personality mindset traits by reflecting how an agency perceives itself, and its possibilities in relation to its environment. In other words, there is a close correspondence between identity and mindset of the personality, and this could be reflected in variations of

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

2.6. Configuring Traits

CAT has been formulated as a personality theory of cognition/affect that is hierarchically and recursively embedded in agency. Its autopoietic nature is delivered through operative intelligence, referring to the capacity for beliefs, values, emotions, attitudes and knowledge that can be assembled in an operative function. In the normative personality, ontologically distinct traits exist, each having bipolar options with different epistemic states. Consider the operative system of the personality with a cognition trait that may take one of two bipolar values: Hierarchy and Egalitarianism. The hierarchical distribution of roles is taken for granted and to comply with the obligations and rules attached to their roles ([

83]:16). An egalitarian approach promotes the view that people recognise one another as moral equals who share basic interests. There is an internalisation of a commitment towards cooperation and to feelings of concern for everyone’s welfare. There is an expectation that people will act for the benefit of others as a matter of choice. Sagiv and Schwartz, ([

51]: 179-180) were concerned with cultural values in the organisation and distinguished between them by assigning two bipolar states to each identified value. In hierarchy, agents belonging to an agency population, are expected to comply with role obligations and to put the interests of the organisation before their own. Egalitarian organisations are built on cooperative negotiation among employees and management ([

51]: 180). Concerning affect, the operative system also has the two options of Dominance (relating to the imposition of control) and Submission (relating to compliance). These interact with other traits through emotional forms of intelligence.

The figurative system of the personality model also involves the figurative trait, which can take one of the values of Mastery plus Affective Autonomy, and Harmony. The former is concerned with self-assertion and egocentric/altruistic ends, the latter with an appreciation of others as opposed to their exploitation. The third domain of personality is the cognition/affect system. The cognition system has a trait that may take values of either Intellectual Autonomy or Embeddedness. Since this system provides self-stabilisation for the personality, whether it has an Intellectual Autonomy or an Embeddedness orientation respectively determines whether it is Collectivist or Individualist in its nature. In the affect system, the affect trait may take values of either Stimulation towards the ascendency of emotional attitude or a balance with Containment. Containment is the other value the trait can adopt which delivers dependability and restraint. The tri-domain personality model sits inside an agency model that has cultural and social functionality in both cognition and affect. Cultural functionality provides agency self-stabilisation, and social functionality determines its mode of interaction with its environment. The trait for the cultural system in cognition arises from Sorokin [

55] and may take the values of Sensate (materialism) or Ideational (ideas). The social trait is an imperative for social behaviour, determines agency’s orientation in the environment, and directs its potential for actions, interactions, and reactions that (re)constitute the social environment [

83]. These cultural values mutually interact in any culture, and over time may take ascendency over the other as societies change. Idealistic cultures combine elements of Sensate and Ideational cultures in a balance.

The cognition social trait is ultimately responsible for how policy will be applied (cf. [

84]), this influenced by the social affect trait. This trait originates from the cognitive style theory of Witkins et al. [

85] for whom an event occurs in a field that defines an environment or context. They then differentiated between field-dependent individuals who are likely to be Patterners and Field-independent individuals are likely to be Dramatisers. Patterners tend to focus on details while Dramatists tend to rather see the big picture. Shotwell et al. [

86] then adopted these concepts of Dramatising and Patterning in their study on cognitive style. Seitz [

87] notes that in their investigation of cognitive style, they recognised the dual modes of engagement relating to either constructive or symbolic play. Constructive-object play by “Patterners” produced a relatively high incidence of metaphoric behaviours connected with perceptual and enactive metaphors. In contrast symbolic play by “Dramatists” produce a relatively low incidence of metaphoric behaviours. Constructive behaviour pertains to physically manipulating objects, while metaphoric behaviour uses symbols and metaphors to represent abstract concepts. For Rosenberg [

88], cognitive style can be seen as a trait with dynamic properties.

Distinction between Dramatists and Patterners has developed (cf. [

83,

89]). Dramatist are motivated by individual goals and interests, shaped by the situation and the means available. Agents act in self-interest and form social contracts with others based on mutual advantages and expectations. Communication and individual relationships are essential for creating meaning and identity. Dramatists prefer symbolic and social activities, and are comfortable with narrative and persuasion. They express their social contracts through social interaction, and value communication and individual relationships as sources of meaning and identity. In contrast, Patterners are people who seek knowledge and competence, and who are interested in understanding how things work and finding logical solutions. They form social contracts with others based on mutual respect and competence, and they value communication and individual relationships as a way of learning and improving. They prefer constructive and mechanical activities, and pursue their own goals and interests through the use of logic and rationality. They are exploratory in their use of logic and symbols. Patternism as distinct from Dramatising, has the key values of symmetry, pattern, balance, and the dynamics of social relationships. There is some connection between Dramatising social orientation and Sensate cultural orientation, while Patterning social orientation is likely to be more connected with Ideational cultural orientation ([

90]:16). Park [

90] tested the performance of organisations under the influence of culture and has shown that that of Dramatisers was significantly more successful than those of Patterners. Any agency develops its own schema (or self-schema) as part of the figurative system. This will include ideology, ethics and goals, and can serve as a self-script for a Dramatising appearance in a given social context. If in a specific social context, the figurative self-schema is appropriate then self-script Dramatising will turn out to be effective, and it will contribute to success. In the affect system, emotional climate traits may be either missionary or empathy, the former imposing perspectives on others, the latter being responsive to others. In the affect agency, the cultural domain is concerned with emotional climate through values of either fear or security and the social domain where the trait may take missionary or empathetic values.

2.7. Configuring Sociocognitive Style

While social relationships can influence cognitive style by affecting, for example, social learning or social influence on cognition, cognitive style can influence social relationships by affecting, for example, social network diversity. Social relationships and cognitive style can also interact to influence outcomes. The explanation for this is as follows. Cognitive styles affect social relationships [

91], for instance, by influencing how agents perceive, think, solve problems, interact, how they form social bonds, and how interactive influence develops, and the formation of inter-agent compatibility or conflict. Similarly, social relationships affect how people develop and modify their cognitive style through social learning, and this then links to the formation of social relationships [

75].

At this point we shall see that there is value in relating the concepts of Patternism/Dramatism to those of Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft. Summarising, Gemeinschaft is connected with informal arrangements and emotion, while Gesellschaft is connected with formal arrangements (like contracts) and rationality. In contrast, Patternism is about symmetry, pattern, balance, and the dynamics of social relationships, while Dramatism is about goal formation for self-centred benefit and social inter-agent contracts. Hence, there is a relative connection between Gemeinschaft and Patternism and Gesellschaft and Dramatism, and while they may not be coincident broadly there is a respective connection between Patternism/Dramatism and Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft.

However, it is important to remember that Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft become modes of expression (and effectively trait values) that describe social relationships, and these enable and shape interactions between agents in various contexts. Patterning/Dramatising are cognitive style trait values that describe the way in which agents process information. One can produce a new configuration that links the possible acquirable values of social relationship and cognitive style. This will result in what we shall call a sociocognitive style, having both a social (this embracing the political) and a cognitive dimension that better describes social organisation, or more appropriately, sociocognitive organisation.

The new configuration of sociocognitive style is a formative mindset determined through combinations of the dualities (Gemeinschaft, Gesellschaft) and (Patternism, Dramatism). In the same way that Gesellschaft social organisational structures may be embedded within Gemeinschaft ones or vice versa, so Dramatist operative trait values may combine in some way with the Patterning operative trait value to provide interactive context that is sensitive to influences on behaviour. The sociocognitive style configuration redefines the nature of sociocognitive organisation as related to the work of Tönnies. Now, we are aware that Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft are concepts from sociological theory that describe different types of agency based on their inter-agent (social) relationships, recognising that while these relationships are of primary importance, a multiplicity and interplay of other influences shape sociocognitive organisation that derive from other traits represented in Mindset Agency Theory, relative to context. Patterning and Dramatising are concepts used in cultural anthropology to describe different ways in which agencies create meaning and order. The overlap between the two pairs of dualities may be relatively easily identified in terms of the relationships among the agents of an agency. The similarities between Gemeinschaft and Patterning occur because both are associated with agencies that have strong bonds of solidarity, loyalty, and trust among agents. They tend to have a low degree of differentiation, complexity, and conflict among them, and a high degree of stability, continuity, and harmony in their interactions. Gesellschaft and Dramatising are both associated with agencies having weak bonds of solidarity, loyalty, and trust among agents. Due to their characterisation of being associated with impersonal and formal relationships, they also tend to have a high degree of differentiation, complexity, and conflict, with a low degree of stability, continuity, and harmony in their interactions. However, the differences between the pair of dualities is that Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft are optional trait values that describe intangible qualities in structural relationships. These provide an operative agency potential, delivering such phenomena as polity and laws. Patterning and Dramatising are trait values that relate to cognitive style, this also reflecting on the intangible psychological processes and patterns of behaviour that influence the cognitive-affective processes and actions of agents. These are shaped by agent experiences, cultural norms, and other social factors. It is therefore plausible that there is a connection between social relationship and cognitive style represented through sociocognitive style. This trait may deliver operative coherence if there is a similarity match between social relationships and cognitive style, but operative incoherence if there is a mismatch between them. This suggests that the sociocognitive style trait can take values from a coherence-incoherence duality. Sociocognitive style can also take intermediate values that reflect different degrees of operative coherence or incoherence. A high degree of coherence means that in sociocognitive style, the agency’s social relationships and cognitive style take values that are consistent with each other, while a low degree of coherence means that they are inconsistent with each other.

2.8. Multiple Contexts

One possible way to distinguish between the multiple contexts is to consider whether one is looking at the macro-level or the micro-level of social phenomena, and whether focus occurs on the similarities or the differences among the agents. Additionally, there may be contexts within contexts that influence how agents perceive and interact with each other in different situations. For example, consider an agency that has a Gesellschaft context at the macro-level, where the agents have weak bonds of solidarity, loyalty, and trust, and where they face a high degree of differentiation, complexity, and conflict in their interactions. However, at a more micro-level of specific subgroups or individuals, like ethnic minorities, civil society organisations, or political leaders, there might be a Gemeinschaft context, where there exist strong bonds of solidarity, loyalty, and trust, and where there is a low degree of differentiation and complexity. Other ways of defining context are also possible, for instance where the agency maintains a set of principles that requires Gemeinschaft related processes, even where they might be underlying Gesellschaft processes at work.

In this potential for increased complexity, an agency may have a coherent sociocognitive style trait if its cognitive style matches its social relationships at the relevant level of analysis and context. For example, an agency may have a coherent sociocognitive style trait if it has a Patterning-type cognitive style at the macro-level with a Gemeinschaft-type social relationship, or if it has a Dramatising-type cognitive style at the micro-level where it has a Gesellschaft-type social relationship. Conversely, an agency may have an incoherent sociocognitive style trait if its cognitive style mismatches its social relationships at the relevant level of analysis and context. The degree of coherence or incoherence in an agency’s sociocognitive style trait may have implications for its performance and outcomes in different situations and contexts.

Now, an agency with operative intelligence/autopoietic processes has the capability of maintaining its identity and viability through self-regulation. Its stability can be expressed in terms of the degree to which it can sustain its autopoietic processes in different situations and contexts. This can be related to the sociocognitive style trait. An incoherent sociocognitive style might affect the stability of the agency by disrupting its autopoietic processes. The mismatch between cognitive style and social relationships might impair the agency’s ability to produce and regulate its own structures, functions, and behaviours that define its identity and viability. The more severe, frequent, and prolonged the incoherence is, and the more critical the level of analysis and context is for the system’s autopoiesis, the more likely the agency is to lose its coherence, integrity, or adaptability. This might compromise the agency’s capacity to cope with environmental changes, internal disturbances, or external challenges.

Furthermore, focusing on similarities among the agents in an agency, there may be a coherent sociocognitive style trait, where they have a Patterning cognitive style that matches their Gemeinschaft social relationship. They share common values, norms, and beliefs that guide their behaviour and communication. Focusing instead on the differences among the agents, they may have an incoherent sociocognitive style trait, where they have a Gesellschaft social relationship that mismatches their Dramatising cognitive style. They express their individuality, creativity, and diversity through their behaviour and communication. Therefore, distinguishing between the contexts may depend on the perspective and the purpose of an analysis, and there may not be a clear-cut distinction between coherent and incoherent sociocognitive style traits, but instead a continuum or a spectrum of possibilities.

2.9. The Determinant for Sociocognitive Style

Until now we have discussed the sociocognitive style trait, but we have not considered how it determines its values of coherence/incoherence. We are aware that sociocognitive style is defined by the connection between social (or more broadly, sociopolitical) relationships and cognitive style. Social relationships refer to the predominant use of either communal or contractual bonds to relate to others, while cognitive style refers to the predominant use of either patterns or narratives to organise and interpret information. We have explained that sociocognitive style can be expressed in terms of the four traits: Gemeinschaft, Gesellschaft, Patterning, and Dramatising. Summarising: Gemeinschaft is the social relationship trait that involves using emotional, personal, and cooperative bonds to form and maintain close and loyal groups; Gesellschaft is the social relationship trait that uses rational, impersonal, and competitive bonds to form and maintain remote and contractual groups. Patterning is the cognitive style trait, and uses logical, analytical, and abstract thinking to create and apply general rules and principles; Dramatising is the cognitive style trait and uses intuitive, creative, and concrete thinking to create and apply specific stories and scenarios. We earlier noted that social relationships and cognitive style interact, resulting in a dominating pairing between their traits.

This has relevance to Multiple Identity Theory. Public identity, principally determined by operative trait interaction with other traits, is an agency self-schema projected to the social environment in order to represent itself as it wishes. It is both a determinant and is determined by cognitive style. Personal identity, similarly principally determined by figurative trait interactions with other traits, is a personality self-schema that the agency has in relation to itself, and reflects how it feels and thinks about itself. It influences social relationships by shaping how people perceive, interpret, communicate, cooperate, and collaborate with others and with themselves in different social contexts and situations.

When personal and public identities are coherent together, agency can express its true self and values in different contexts to which identity is sensitive. It can also pair its social relationship and cognitive style traits in a way that suits its identity and purpose. When personal and public identities experience a schism, then this will be a consequence of the interactions between traits. In this case public identity may become a false self, when psychological disturbances are possible that can result from conflict or stresses that the fracture has delivered. Identity schisms can be reflected in sociocognitive organisation by affecting trait formation and the relationship between social organisation and cognitive style. The interaction between cognitive style and social organisation can be seen as a schema in the sense that it is a cognitive structure that serves as a framework for one’s knowledge about people, places, objects, and events. The mechanism that is caused by the interaction between cognitive style and social organisation is the sociocognitive mechanism. This, and its accompanying processes, involves schema activation, and the conscious organisation of experiences and categories that structure the environment, including the influences of other traits.

Just as mindset traits influence behaviour, so does identity [

10], and both are dynamic and adapt to changing contexts, and interact through mutually reflexive processes. Identity may be thought of as a self-schema that connects an agency to others, reflecting feelings and thought about self and how it wishes to be seen and treated by others. It is influenced by factors like emotions, memories, experiences, personality, knowledge, values, beliefs, goals, motivations, culture, and social categories. Mindset traits are the distinctive agency qualities or characteristics that influence and reflect perception, feeling, thinking, and behaviour with respect to context and situation.

Recall the proposition that identity is an emergent phenomenon resulting from the interaction between mindscape traits. The emergent phenomenon provides mindset context that feeds back to the interactive traits, and this can affect all traits resulting, for instance, in adjustments in behaviour, cognition, affect, and motivation, and perceptions of context can be altered. Its emergence is a self-schema that relates an agency to others, reflecting its feelings and thoughts about itself, and how it wants to be seen and treated by others. Identity is influenced by various factors, such as emotions, memories, experiences, knowledge, values, beliefs, goals, motivations, culture, and social categories. However, mindscape traits are also part of these factors, as they reflect how the agency perceives itself and its possibilities in relation to its environment. Therefore, identity emerges from the interaction and feedback between mindscape traits and other factors that shape the agency’s sense of self.

2.10. From Traits to Mindsets

We are aware that collective action is identity dependent. Following Yolles and Fink [

10], one can identify possible organisational mindsets, and these indicate the normative orientation of an agency that creates its personality attributes. Five ontologically distinct traits correspond to

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. We present the cognition and affect traits in

Table 1 and

Table 2 respectively.

The relationship between cognition and affect traits is shown in

Table 3. The traits can coalesce into groups that define cognition and affect mindsets, as shown in

Table 4. These are strategic personality mindsets since they are composed of only three personality traits. Another agency mindset model can be constructed for agency cognition and affect mindsets [

10], where each mindset is composed of five traits. They have also delivered a methodology that can establish whether there are likely to be agency-personality identity conflicts, resulting in a comparison between personality and agency mindsets. The methodology developed by Yolles and Fink involves differentiating between the agency and personality identities as indicated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. These two forms of identity are equivalent to the personal and social identities where for Lupien [

92], personal identity refers to self-definition in terms of personal attributes, and social identity refers to self-definition in terms of social category memberships. For Ashforth and Mael [

93], the latter provides the mental mechanisms that make group behaviour possible. Differences indicate an identity conflict, the nature of which is determined by the mindsets involved. This can occur concerning the cognition system or the affect system. The theory recognises that there are two forms of identity, cognitive and emotional. Cognitive identity is meant a cognitive structure that provides a frame of reference for interpreting self-relevant cognitive information for solving problems, and making decisions (cf. [

94]). Emotional identity is an agency’s awareness of affective attributes associated with social interactions and includes how agencies define themselves by their (handling of) emotions and how others may use emotions as social markers to define an agency or its agents [

95]. It involves an affect structure that provides a frame of reference for interpreting self-relevant emotional information for recognising and imitating the attitudes, thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of others or groups and becomes assimilated when it becomes the internal motivation for cognitive identity (cf. [

96]).

Personal and agency identities are different, and identity conflicts may arise which give a sense of discrepancy between the beliefs, norms and expectations held by an individual [

97]. When identity conflicts occur that can be classed as cognition identity conflict, a consequence can be irrational behaviours [

98]. Similarly, when affect identity conflicts arise, a consequence may be an internal emotional tension that creates an emotional climate/emotional attitude dilemma (an elaboration of the security dilemmas of Heraclides [

99], and leads to recalcitrant emotions: those emotions that are in tension with agency’s evaluative (cognition) judgements [

100].

Noting that all conflicts are identity conflicts [

101], a methodology has been developed that provides a relatively simple theoretical and pragmatic approach to evaluate whether an agency has a cognition identity conflict [

10], here extended to affect identity conflicts. In Table 8 we present personality mindsets. However, the Collectivist or Individualist nature of agency may not only depend on the tendency of its personality but also on its cultural and operative orientations. Here, then, it is clear that Collectivism is directly associated with embeddedness and Individualism with Intellectual Autonomy.

In

Table 5 we present both personality as 3-trait mindsets, and agency as 5-trait mindsets for both affect and cognition. The methodology uses analyses texts produced by agencies by looking for trait keywords associated with each mindset type, statistically evaluated, and the 3-trait personality and 5-trait agency mindsets compared for the best fit, from which identity conflicts can be inferred. Where the two mindsets are the same, there is no identity conflict, but where they are different, there will be, its severity depending on the nature of the personality-agency mindsets identified. While it is not certain how affect and cognition mindsets relate, we have connected them in

Table 5 according to a particular rationale. This is because connecting ‘Intellectual Autonomy’ with ‘Stimulation’ implies that the affect ‘Stimulation’ is cognitively directed primarily at freedom, creativity, curiosity, and broad-mindedness and only secondary to values of ‘Affective Autonomy.’ It is similarly possible to make connections between embeddedness and containment. Thus, for instance, following Matsumoto [

102], containment is a means by which power holders organise relationships through which embeddedness occurs. Now, in

Table 5 only some of the mindset types are listed. This is because 32 agency mindset types are possible using the various combinations of the five trait types, though it is not currently known if all of these are stable. Those that are listed are quite possibly stable, though research here is wanting. So, it does need to be tested as to whether Stimulation-oriented agencies tend to see Security, but vary according to whether they are Missionary or Fear oriented, and Containment-oriented agencies are driven by Empathy.

Yolles and Fink [

10] undertook the above identity analysis for Donald Trump, the US president during the period 2017 to 2021. It uncovered an identity conflict that would be consistent with a narcissistic personality disorder. Such an analysis could similarly be applied to ROs to determine whether they have identity conflicts. Now, identity conflict happens when an agency encounters difficulties in reconciling different components of identity that prescribe behaviours which are incompatible with each other [

103]. Identity is important to collective action because it explains the coherence and organisation of agencies as collective actors [

104]. This is elaborated on by Yolles and Fink ([

10]: 65), who explain that the development of identity pathologies can be reflected in the multiple identity literature and that a theory of cleavage between multiple identities can arise that is indicative of trait instabilities and personality pathologies. Trait instabilities result in the development of uncertainties in processes of communication and cooperation, leading to likely instabilities in any capacity to organise collective action.

It is likely that where there is a conflict between personality mindset and agency mindset (the latter also involving cultural and social traits), so that inherent potential conflicts are agency medial, i.e., arise internally. Thus, for instance, where personality is Individualist and agency involves Ideational culture and Pattering traits, Individualism is converted to a form of uncommitted conflictual Collectivism that lies in conflict with its personality imperatives.

It must be noted here that while agencies can be associated with mindsets, these can change with qualitatively distinct contexts, the qualities being defined by a set of parameters that are different from those in another distinct context. This has been shown by Tamis-LeMonda et al. [

105] (cf. [

10]), who were interested in the socialisation of children by their parents concerning the dominating influence of Collectivist and Individualistic mindsets, thus indicating a potential for adaptive mindsets with contextual change. While we have shown that there are a variety of Collectivist and Individualist mindsets, there is still an effective but nuanced variety of Collectivism-Individualism dualities. This is dynamic in that the duality of coexisting cultural value systems often has one which dominates to some degree over time. This duality may be viewed as being conflicting, additive, or functionally dependent, and the interaction between the dual parts, which are individually dynamic, can change across situations, develop over time, and have responsiveness to sociopolitical and economic contexts. The dominant cultural tendency as set in a given situation should be seen as a variable that is sensitive to fluctuating contexts, contained within a single continuum that maintains characteristics that can embrace both value sets. This is reflected in the different traits that may be associated with any of the Collectivist or Individualist mindsets. The dynamic nature of the Collectivist-Individualist relationship also implies discontinuities in mindset shifts that impact behaviour so that while the traits that compose mindsets may be subject to continuous variation, they coalesce into only a few stable personality states that can result in particular modes of behaviour. It may also be noted that the potential for a shifting Collectivism-Individualism orientation is reflected in the Gemeinschaft/Pattering and Gesellschaft/Dramatising duality dynamics.

This also applies to the political sphere, where the context may be identified in terms of collections of cultural values. For Boeree [

106] these can coalesce into 7 worldviews, and within the context of this paper, the two that are of particular relevance are: (a) political epistemological liberalism characterised by tolerance towards political differences, through variations like the shift towards political neoliberalism, characterised by neoliberalism migrated to right-wing political conservatism, and a trending intolerance toward other political positions [

107]; and (b) political authoritarianism characterised by intolerance towards political differences through the rejection of political plurality, and the use of strong central power to preserve the political status quo, but with variations like mercantile authoritarianism represented by market capitalism, rule by law, and nationalism [

108].

3. Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has reconfigured Cultural Agency Theory by integrating Tönnies concept of social organisation, and connected the adaptation to the derivative mensurable Mindset Agency Theory. This theory will in due course be applied to ASEAN to explore its mindset in the following part-2 paper. The theoretical approach is one of complex adaptive systems that is well founded on cybernetic principles, and is an approach that conforms to critical realism [