1. Introduction

Nowadays, community pharmacists (CP) are considered to be healthcare providers [

1]. In Europe, pharmaceutical care is defined as “the pharmacist’s contribution to the care of individuals in order to optimize medicines use and improve health outcomes” [

2,

3]. Changes in the role of pharmacies in the community underlie this description of the pharmacist’s function. Day-to-day pharmacy practice is no longer restricted to the dispensation of medicines. Professional pharmacy services currently include vaccinations, triage services, medication reviews and pharmaceutical planning [

4].Over time, for many patients the CP has become their first contact with the healthcare system. In France, less restricted access to medicines has made this possible. Indeed, the offer of over-the-counter (OTC) medications has expanded and now includes the dispensing of drugs previously available only on prescription. The CP is also perceived as a privileged interlocutor for complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) (with around 100 hours of initial training in CAMs), making a bridge between conventional medicines and natural health products [

5]. Finally, changes in French legislation over the past 10 years have changed the CP from a simple retailer to a pharmaceutical services provider [

1], not only for patients but also for other healthcare professionals, including physicians. The CP has become a co-decision-maker, especially when working in an integrated-care environment.

“With greater power comes greater responsibility” [

6]: could be the statement describing this change in function that ranges from the management of minor ailments to the provision of pharmaceutical care for patients with chronic conditions [

7]. Responsible practice implies that it is Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) [

8]. The adoption by CPs of an approach based on EBP has been studied in terms of perceptions [

9,

10,

11,

12], evaluation of professional practices [

13,

14,

15], the evaluation of interventions during initial training [

16,

17] or in everyday practice [

18,

19].

The studies that have evaluated EBP in the community pharmacy setting have mainly focused on OTC drugs. In contrast, the primary objective of the present study was to assess attitudes and the application of EBP, whatever the nature of the health product (OTC medication, CAMs or prescription-only medicines).

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out among CPs and 6th (final) year pharmacy students practicing in a community pharmacy or studying in France. In France final-year pharmacy students taking the CP speciality undertake an internship of 6 months in a community pharmacy. Pharmacy technicians and students at earlier stages in their pharmacy studies were not included. The 40-item online questionnaire (Supplementary Material S1) was sent between 1st April and 1st June 2018 using a public email database containing more than 7,000 different contacts of CPs. The questionnaire was also posted on five Facebook groups (restricted to CPs and pharmacy students).

The primary objective of this study concerned the multiple-choice part of the questionnaire that presented four fictional cases typical of those encountered in the daily practice of community pharmacists. The topics were the replacement of influenza vaccination by a homeopathic product, a dietary supplement (red yeast rice) as a substitute for statins, the use of the herbal preparation St. John's Wort for moderate depression, and the choice of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (supplementary material S1). For each case, the respondents had to choose one of the four proposed responses that best corresponded to their current professional practice.

To give the respondents confidence and to encourage them to complete and return the questionnaire, for one case (n° 2 – St John’s Wort) all the answers proposed corresponded to good EBP. This was also to show that the questionnaire was not intended to judge CAM if its use was backed-up by scientific evidence. The pharmacists’ choices of response to this case were not analyzed. The questionnaire also collected socio-demographic data about the respondents, the sources of information they usually consulted concerning allopathic medicines and CAM, and any continuing education they pursued (supplementary material S1).

A pilot version of the questionnaire had been tested by 11 community pharmacists, physicians, university lecturers and hospital pharmacists, and 30 pharmacy students.

The primary outcome was the total score from the multiple-choice responses to the clinical cases. For each case, 4 points were attributed for the response closest to EBP, 3 points if the respondent knew the best EBP response but felt they could not say that to the patient, 2 points if the respondent did not know the appropriate EBP answer, and 1 point if the response was counter to EBP. Thus, the minimum total score was 3 and the maximum score 12. The ranking attributed to responses had been justified by a review of the literature that included the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the French “La Revue Prescrire” (a French independent publication on professional practice & drugs, produced by a network of volunteer experts) and the recommendations of the French health authorities and/or professional associations if necessary (Supplementary material S2) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Based on the distribution of multiple-choice scores a threshold was determined such that respondents could be categorised into two groups, EBP positive (higher score) and EBP negative (lower score).

The second part of the questionnaire collected data on the type of pharmacy where the CP worked and the pharmacist’s status, whether they attended any continuing education and the sources of information they usually consulted.

Analysis: We present qualitative variables using number and frequency, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. To compare mode of continuing education according to pharmacist’s status, we used the Chi2 test. Univariate tests were conducted to evaluate the association between responses and the profile of the participants and the pharmacies where they worked. A multivariate analysis with logistic regression was conducted using variables selected from the univariate analyses (having a p ≤ 0.20) that might explain the adherence of participants to EBP (EPB +, or EBP -). The final model was selected after a manual step-down selection procedure. An a priori alpha of less than 0.05 was considered as significant. Stata 15 software for OSX was use for data analyses

The statistical analysis and content of this article are consistent with STROBE international recommendations to report cross-sectional studies (if applicable).

3. Results

Out of the 599 pharmacists and 6th year pharmacy students who returned the survey, four questionnaires were incomplete. Finally, 595 completed questionnaires were included in the database for statistical analysis. The mean age of the respondents was 38 ± 11.7 years and they came from all 13 metropolitan regions of France, as well as the overseas territories (

Table 1). Given the use of Facebook groups for which the number of pharmacists who accessed the site but did not respond to the questionnaire was not known, the response rate could not be calculated.

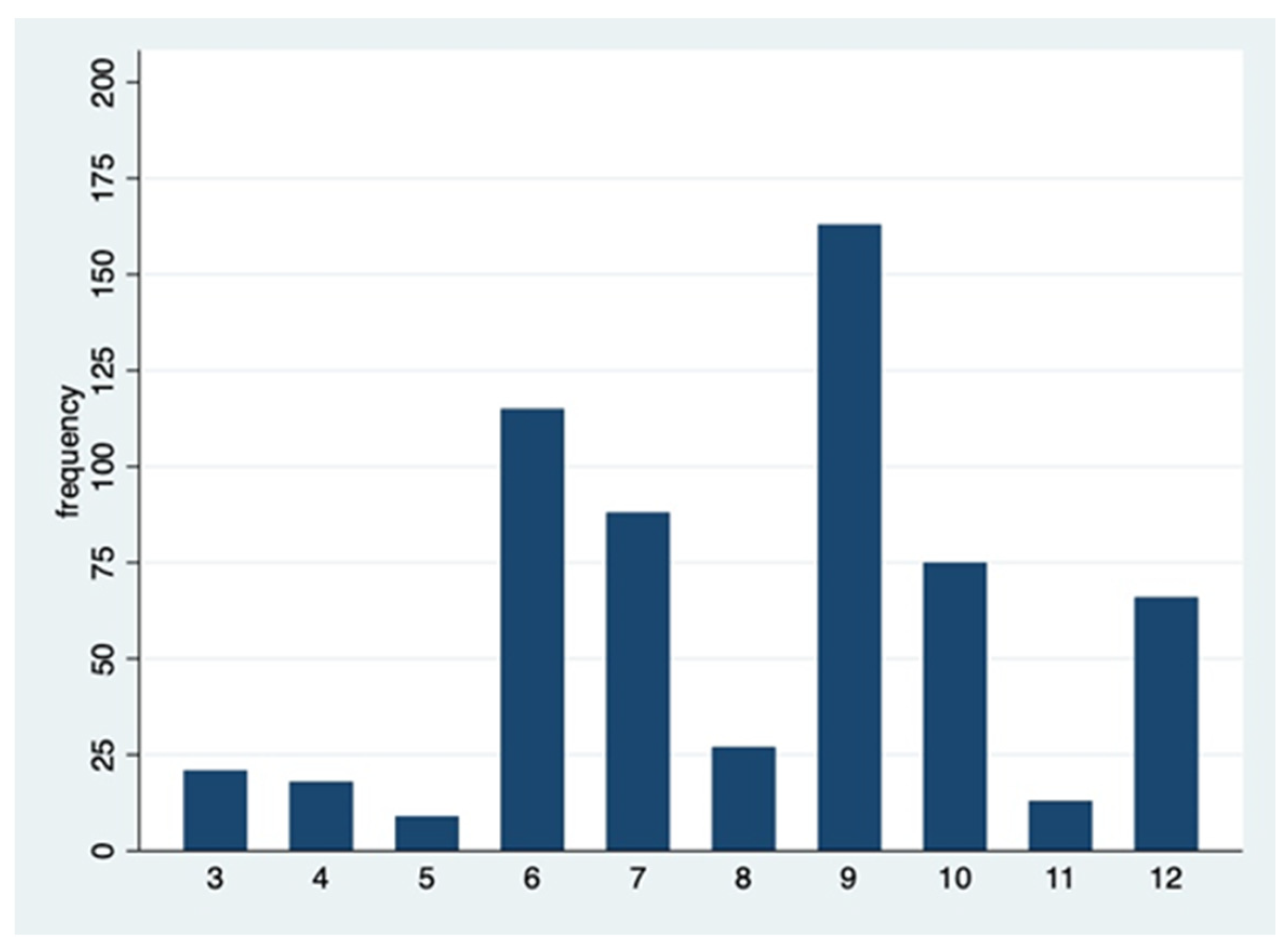

Table 2 shows the distribution of pharmacists’ responses to the cases presented in the questionnaire (except case 2 which was not scored as all responses were good EBP) and

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the total score, supporting the categorization of responders into 2 groups with a threshold between 7 and 8 (EPB negative: score ≤7 and EBP positive: score ≥8).

French pharmacists use a variety of continuing education methods (both self-instruction or following organized courses) to increase their knowledge and keep up-to date with developments concerning both conventional medications, devices etc. and CAMs (

Table 3).

“La Revue Prescrire” (or “Prescrire”) is a monthly publication of mainly reviews in French that address developments in disease management, medications, and medical techniques and technologies. Prescrire contains no advertising, and is financed by subscriptions. Prescrire mainly publishes reviews prepared by its own staff. It is run by a not-for-profit organization and is independent of the pharmaceutical industry

After qualifying as a pharmacist in France (Pharm D: 6 years of pharmaceutical studies plus an internship) the most frequent post-graduate courses taken by CPs were orthopedics (mandatory diploma to counsel for medical devices in orthopedics) 48.6% (289/595); homeopathy (these diploma courses were recently withdrawn in public sector schools of pharmacy) 8% (48/595); and home care (diploma in helping dependent patients remain in their homes) 7% (42/595). Many participants had not completed any post-graduate diploma course.

Concerning the topics broached in the cases presented in the questionnaire (homeopathic product instead of influenza vaccination, dietary supplements to replace statins, and CAM instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) the most commonly consulted sources of information are shown in

Table 4.

The logistic regression selected the variables that were positively or negatively associated with the group using EBP (EBP positive) or the group ignoring EBP ((EBP negative). An odds ratio (OR) >1 was positively correlated with the proper use of the EBP and an OR < 1 was negatively correlated with the good use of the EBP. The factors positively correlated with use of EBP were: being a final year student or junior CP (compared to being a pharmacy owner (p <0.01), frequent use of health agency recommendations for guidance p <0.01) as well as reading ”

Prescrire” (p = 0.010), compared to not consulting them. The factors negatively correlated with the proper use of EBP were: the frequent use of information provided by pharmaceutical laboratory sales representatives (p = 0.012), relying on personal experience (p = 0.016), and/or having a diploma in homeopathy (p = 0.024) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

The choice of responses to a questionnaire that presented different clinical cases gave us some insights into the knowledge and use of EBP by community pharmacists and associated factors such as their status in the pharmacy, the sources of information they usually use and whether they pursued any continuing education. Most previous surveys focusing on EBP in community pharmacies used qualitative methods, questionnaires with multiple open text answers, or ordered and Likert scales [

10,

11,

12,

14].

More than 80% of questionnaire respondents checked influenza vaccine as the first-line measure for influenza prevention. However, 12% affirmed that they would advise replacing influenza vaccine by the homeopathic product “Influenzinum” (a homeopathic product in the form of granules containing a dilution of the current year’s influenza vaccine), and considered it as an effective option, despite any scientific proof. These answers need to be to be considered in the context of French attitudes towards influenza vaccine and homeopathy at the time the questionnaire was distributed (2018). The authorisation for community pharmacists to perform influenza vaccinations was introduced in 2018. Likewise, homeopathy has been reimbursed by the French national health insurance scheme for decades. However, its place in drug therapy and its reimbursement by the French social security has been criticized for several years by both the pharmaceutical and medical professions. This controversy finally led most French universities to discontinue their university diploma courses in homeopathy. Moreover, the study shows that pharmacists who hold a university diploma in homeopathy are more inclined to make decisions that are not supported by EBP. Thus, the impact of homeopathy courses does not seem to be confined to the sole practice of homeopathy itself. Perhaps, the fact of undergoing training in homeopathy reflects adherence to a mode of reasoning based on beliefs (or theories) without taking into account scientific evidence.

The survey showed that some pharmacists are directed to non-EBP information sources in courses run by the pharmaceutical industry, rely on their personal experience and consult informal non-peer reviewed handbooks (often provided by sales representatives and available in the dispensary). Indeed, Hanna et al. [

11] suggested that decisions taken regarding OTC medications and CAMs are mostly the result of personal experience (individual, familial or patient feedback). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the product’s safety seems more important than the product’s efficacy for some pharmacists [

11,

13,

14,

15]. In view of the results of qualitative studies on OTC sales conducted by Hanna [

11] and Rutter [

13], when in doubt and faced with commercial pressure, some pharmacists choose to secure the sale rather than giving EBP advice. However, in the present study, for some pharmacists, an alternative stance was seen in all three cases. This consisted of giving the patient the non-EBP product while at the same time recognizing their action was not EBP.

The case concerning red yeast rice is interesting because it concerns a CAM product containing a phytotherapeutic molecule identical to lovastatin (monacolin K). This active agent in red yeast rice has been assessed according to EBP criteria, however the few randomised studies are relatively small in size [

32]. The monacolin K concentration varies according to how the red rice is prepared and can sometimes contain traces of toxic substances [

33]. The survey showed that nearly half of the respondents would deliver red yeast rice to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients who experienced adverse muscular side effects with a statin and had to discontinue it. While it seems that the pharmacist is making a therapeutic choice based on patient safety, the answers to this clinical case raise questions as to how pharmacists are trained to evaluate the benefit/risk balance.

The survey revealed that the majority of pharmacists still use information sources that are subject to bias. Indeed, the majority of sources used by community pharmacists for documentation on CAM are subject to bias (training from the pharmaceutical industry, personal experience and informal CAM handbooks). This is possibly because high quality randomized trials of CAM are difficult to fund and often have negative results making them difficult to publish (publication bias). These broad figures (except on CAM) are comparable to those from Mamiya et al., [

34] in another international setting: concerning tools for continuing self-development, 34.8% of respondents answered “at home using books purchased by themselves and web searches”, 24.2% “study meeting of medical associations such as Japanese Society of Hospital Pharmacists or Japan Pharmaceutical Association” and 10.8% respondents answered “pharmaceutical companies (wholesalers) study meetings. It should be noted that some pharmacists are not at ease reading English language information, and this might make it more difficult to access reports of high-quality studies published in international journals. Furthermore, it appears that some respondents rely on information from the regulatory authorities, but are often not up-to-date with changes, because they rely on the package inserts only. The results of the multivariate analysis confirm the importance of the source of information used in the choices made, with the use of sources less subject to bias, such as the French review “Prescrire” (the only independent source of information on Drugs in French language, funded entirely by its subscribers), being associated with science-based decisions. The reliance on personal experience and pharmaceutical industry-related training was correlated with decisions not supported by scientific evidence. The results also suggest that making science-based decisions is more frequent among junior pharmacists who use multiple and varied sources of information, unlike more senior pharmacists with more years of experience, but possibly less inclined or with less time to explore news sources. This might also be explained by recent changes in the pharmacy curriculum. Initial training now incorporates teaching modules aimed at developing an EPB culture among pharmacy students. This is particularly the case for teaching modules concerning the critical reading of articles or those in clinical pharmacy. The study was transversal, so conclusions regarding either a change in attitude according to generation (age), or to a phenomenon of erosion during professional exercise cannot be advanced.

As a specification of Evidence based-medicine, evidence-Based Practice in Pharmacy relates to the promotion of “judicious, appropriate and safe use of medicines” [

35]. One of the key issues is education. One of the most important determinants of adult learning is its relevance to clinical practice [

36]. Teaching healthcare professionals to discern the most relevant and independent information source so that they can use it in their practice is essential. It also appears necessary to integrate lessons based not only on EBP but also on applying the principals of EBP to clinical practice in all continuing education courses. It seems unrealistic to expect French community pharmacists to routinely search and critically appraise clinical trial reports in the international literature, particularly due to the language barrier. This is why the regular consultation of up-to-date simplified review articles in independent publications such as “Prescrire” should be encouraged.

There are several potential biases and limitations to our study, particularly concerning the representativeness of the sample. The large number of respondents provides a broad overview of the practices of community pharmacists practicing in France, the respondent profile being comparable to the French pharmacist population in terms of sex ratio. and age. Data collection was carried out via an online questionnaire that had been tested by several community pharmacists, university hospital practitioners and pharmacy students to ensure its coherence, feasibility, and quality. Our sample is slightly younger than that of French pharmacists as a whole, which can be explained by our decision to include student pharmacists in their end-of-study internship in the 6th year. The percentage of pharmacy owners is comparable to national figures. For logistical reasons, we did not contact all French regions, but

Table 1 shows that each targeted region has a weighting in the sample close to its weighting in the national demography of community pharmacists. The questionnaire could be completed in the pharmacist’s free time, allowing the respondent to focus on the benefit/ risk evaluation. It did not take into consideration the external constraints that usually accompany such decision making (restricted time, patient/customer or managerial pressure etc). The self-declarative format of the questionnaire may have induced a bias towards respondents giving what they considered to be the desired responses rather than ones reflecting the pharmacist’s actual everyday practise.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

The data collected from 595 pharmacists allowed us to make an overview of Evidence-Based Practice among French community pharmacists and to highlight some factors influencing their choices. Junior community pharmacists tend to be more willing to apply EBP compared to their more senior colleagues. The sources of information mainly consulted by the pharmacist were also linked to their respect of EBP. These results should be confirmed in a larger study. However, in the meantime one could hypothesize that teaching pharmacy students simple methods to access non-biased sources of information can lead to better EBP. This should also be a challenge for practising pharmacists, who need to keep their knowledge and skills up to date instead of working “from their own experience”.

The EBP approach is still at its beginning among French community pharmacists. Even if our methodology is open to improvement (we don't have a gold-standard for evaluating this EBP approach among pharmacists), our study highlights some encouraging signs: around 40% of pharmacists surveyed have adopted an EBP-compatible approach, a figure indeed overestimated given the over-representation of young pharmacists in our sample. However, more interesting is the qualification of this positioning: in particular, a greater consideration of evidence in decision-making on the part of young pharmacists, combined with greater use of scientifically valid sources of information (recommendations for practice such as those in the "Prescrire" journal). In fact, the two key issues to continuing the EBP trend in community pharmacy practice are to include EBP in the initial and continuing training of pharmacists, and to help them access independent, synopsis and practice-oriented sources of information.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Questionnaire S1: Community pharmacists and their daily therapeutic choices; Table S2: Evidence Based Practice Scoring of Multiple-choice answers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B., B.A. and J-L.B.; methodology, J-L.B..; validation, J-L.B.., formal analysis, C.V.; investigation, L.B. F.V., J- D.B.; data curation, L.B. F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B., F.V. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, B.A, J-D.B., C.V. and <J-L.B. supervision, J-L.B and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Grenoble Alpes University Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, “Ethical review and approval were not applicable as no patients, healthy volunteers or animals were involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available for academic use on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rousseau M-C, Bardet J-D, Bellet B, Allenet B. [How is Clinical Pharmacy perceived by community pharmacists?: “it is to put the patient at the center of the activity, to be interested in his environment, to know how he lives. It is to integrate all of this, well beyond the simple medication”]. Pharm Hosp Clin. 2020;55:377–90. [CrossRef]

- Allemann SS, van Mil JWF, Botermann L, Berger K, Griese N, Hersberger KE. Pharmaceutical Care: the PCNE definition 2013. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:544–55. [CrossRef]

- Allenet B. Let's endorse the international terms: Go for pharmaceutical care ! Pharm Hosp Clin 2021; 56: 227–228.

- Barra M de, Scott CL, Scott NW, Johnston M, Bruin M de, Nkansah N, et al. Pharmacist services for non-hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 23]; Available from: http://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013102/abstract.

- Kwan D, Boon HS, Hirschkorn K, Welsh S, Jurgens T, Eccott L, et al. Exploring consumer and pharmacist views on the professional role of the pharmacist with respect to natural health products: a study of focus groups. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:40. [CrossRef]

- Lee S. Amazing Fantasy #15. Marvel; 1962.

- Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–43. [CrossRef]

- Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. Defining professional pharmacy services in community pharmacy. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9:989–95. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell CA. Attitudes and knowledge of primary care professionals towards evidence-based practice: a postal survey. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10:197–205. [CrossRef]

- Burkiewicz JS, Zgarrick DP. Evidence-based practice by pharmacists: utilization and barriers. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1214–9. [CrossRef]

- Hanna L-A, Hughes C. The influence of evidence-based medicine training on decision-making in relation to over-the-counter medicines: a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20:358–66. [CrossRef]

- McKee P, Hughes C, Hanna L-A. Views of pharmacy graduates and pharmacist tutors on evidence-based practice in relation to over-the-counter consultations: a qualitative study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:1040–6. [CrossRef]

- Rutter P, Wadesango E. Does evidence drive pharmacist over-the-counter product recommendations? J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20:425–8. [CrossRef]

- Castelino RL, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Are interventions recommended by pharmacists during Home Medicines Review evidence-based? J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:104–10. [CrossRef]

- Hanna L-A, Hughes CM. Pharmacists’ attitudes towards an evidence-based approach for over-the-counter medication. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:63–71. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa IC, de Lima David JP, Noblat L de ACB. A drug information center module to train pharmacy students in evidence-based practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77:80. [CrossRef]

- Aranda JP, Davies ML, Jackevicius CA. Student pharmacists’ performance and perceptions on an evidence-based medicine objective structured clinical examination. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11:302–8. [CrossRef]

- Watson MC, Bond CM, Grimshaw JM, Mollison J, Ludbrook A, Walker AE. Educational strategies to promote evidence-based community pharmacy practice: a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT). Fam Pract. 2002;19:529–36. [CrossRef]

- Gilson AM, Xiong KZ, Stone JA, Jacobson N, Chui MA. A pharmacy-based intervention to improve safe over-the-counter medication use in older adults. Res Soc Adm Pharm RSAP. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Prescrire. Homéopathie : toujours pas de preuve d’éfficacité. [Homeopathy: still no proof of effectiveness] Rev Prescrire. juin 2012;32(344):446. Available at https://www.prscrire.org/Fr/3/31/47896/0/NewsDetails.aspx.

- Ernst E. Homeopathy: what does the “best” evidence tell us? Med J Aust. 19 avr 2010;192(8):458-60. [CrossRef]

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Ferroni E, Thorning S, Thomas R, et al. Vaccines for preventing seasonal influenza and its complications in people aged 65 or older | Cochrane. Cochrane Syst Rev [Internet]. 1 févr 2018 Available at https://www.cochrane.org/CD004876/ARI_vaccines-preventing-seasonal-influenza-and-its-complications-people-aged-65-or-older.

- Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CYX. Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s Wort) in depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 01 2017;210:211-21. [CrossRef]

- Linde K, Berner M, Kriston L. St. John’s Wort for treating depression. Cochrane Syst Rev [Internet]. 8 oct 2008 [cité 5 août 2018]; Available at https://www.cochrane.org/CD000448/DEPRESSN_st.-johns-wort-for-treating-depression.

- Prescrire. Millepertuis et états dépressifs. [St. John's wort and depression]. Rev Prescrire. 2004;24(250):362-9.

- ANSES. Avis de l’Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail” relatif aux risques liés à la présence de « Levure de riz rouge » dans les compléments alimentaires. [Opinion of the National Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health Safety” relating to the risks associated with the presence of “Red yeast rice” in food supplements]. Maison-Alfort; 2014 p1-34. Report No.: 2012-SA-0228.

- Klimek M, Wang S, Ogunkanmi A. Safety and Efficacy of Red Yeast Rice (Monascus purpureus) as an Alternative Therapy for Hyperlipidemia. Pharm Ther. 2009;34(6):313-27.

- swissmedic. La commercialisation de préparations à base de Monascus purpureus (levure de riz rouge) est illicite en Suisse. [The marketing of preparations based on Monascus purpureus (red yeast rice) is illegal in Switzerland]. Swissmedic; 2012 p.1-4.

- Prescrire. Levure de riz rouge. [Red rice yeast ]. Rev Prescrire. janv 2015;35(375):18.

- Solomon DH. Nonselective NSAIDs : Adverse cardiovascular effects. UpTodate. 2018.

- Prescrire. AINS et troubles cardiovasculaires graves : surtout les coxibs et le diclofénac. [NSAIDs and serious cardiovascular disorders: especially coxibs and diclofenac]. Rev Prescrire. oct 2015;35(384).

- Ong YC, Aziz Z. Systematic review of red yeast rice compared with simvastatin in dyslipidaemia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016 Apr;41(2):170-9. [CrossRef]

- Dujovne CA. Red Yeast Rice Preparations: Are They Suitable Substitutions for Statins? Am J Med. 2017 Oct;130(10):1148-1150. [CrossRef]

- Mamiya KT, Takahashi K , Iwasaki T and Irie T. Japanese Pharmacists’ Perceptions of Self-Development Skills and Continuing Professional Development. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 73. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield K, Coombes I, Denaro C and Donovan P. Medication Utilisation Program, Quality Improvement and Research Pharmacist—Implementation Strategies and Preliminary Findings. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 182. [CrossRef]

- Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ. 2004 Oct 30;329(7473):1017. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).