Submitted:

06 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

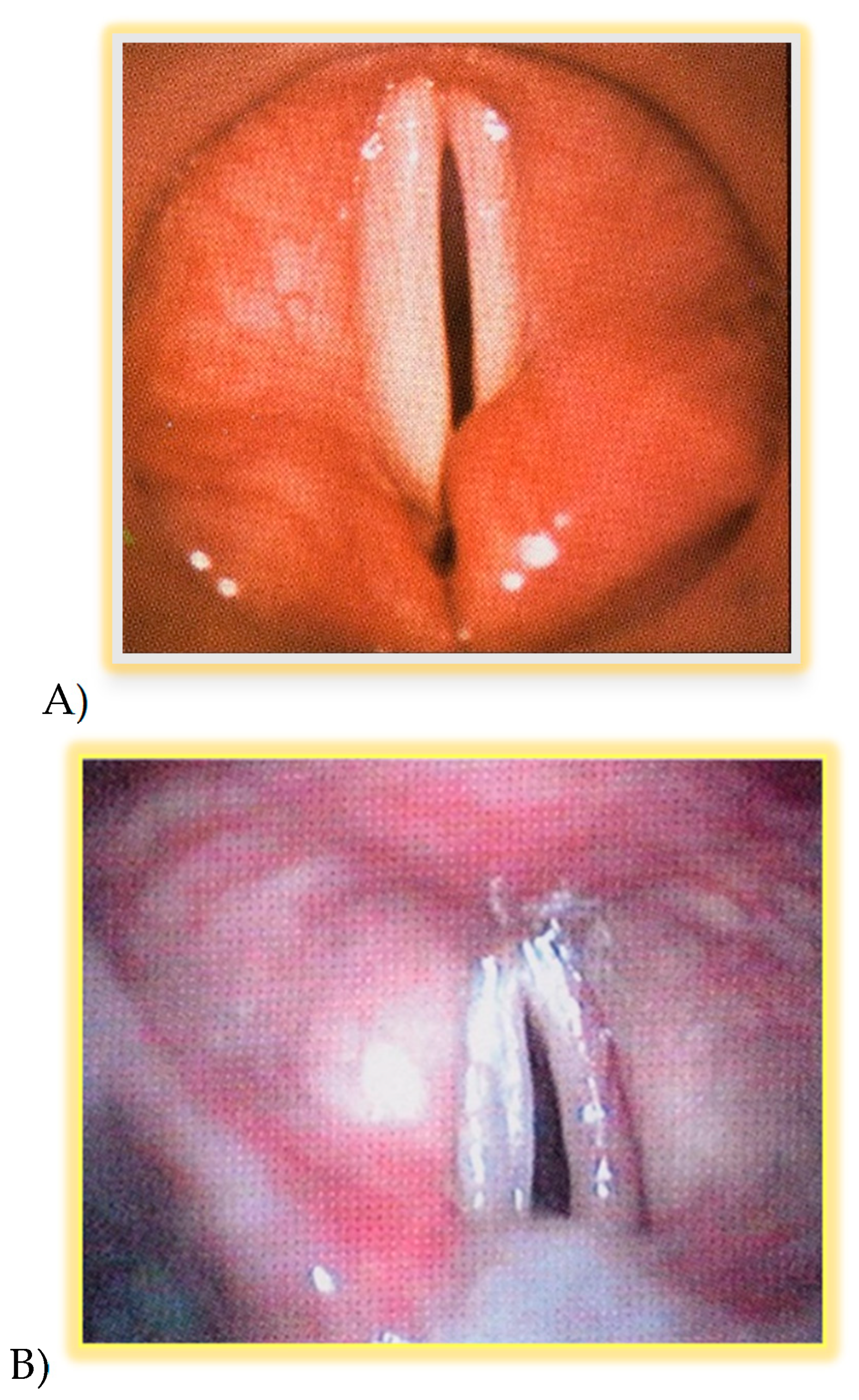

- Vocal folds position following thyroid surgery (glottal gap);

- Timing and resolution of laryngeal defects in total or partial impairment of vocal folds motility;

- The percentage of patients with BVFP who have benefited from voice therapy;

- The percentage of patients with BVFP who underwent laryngeal surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

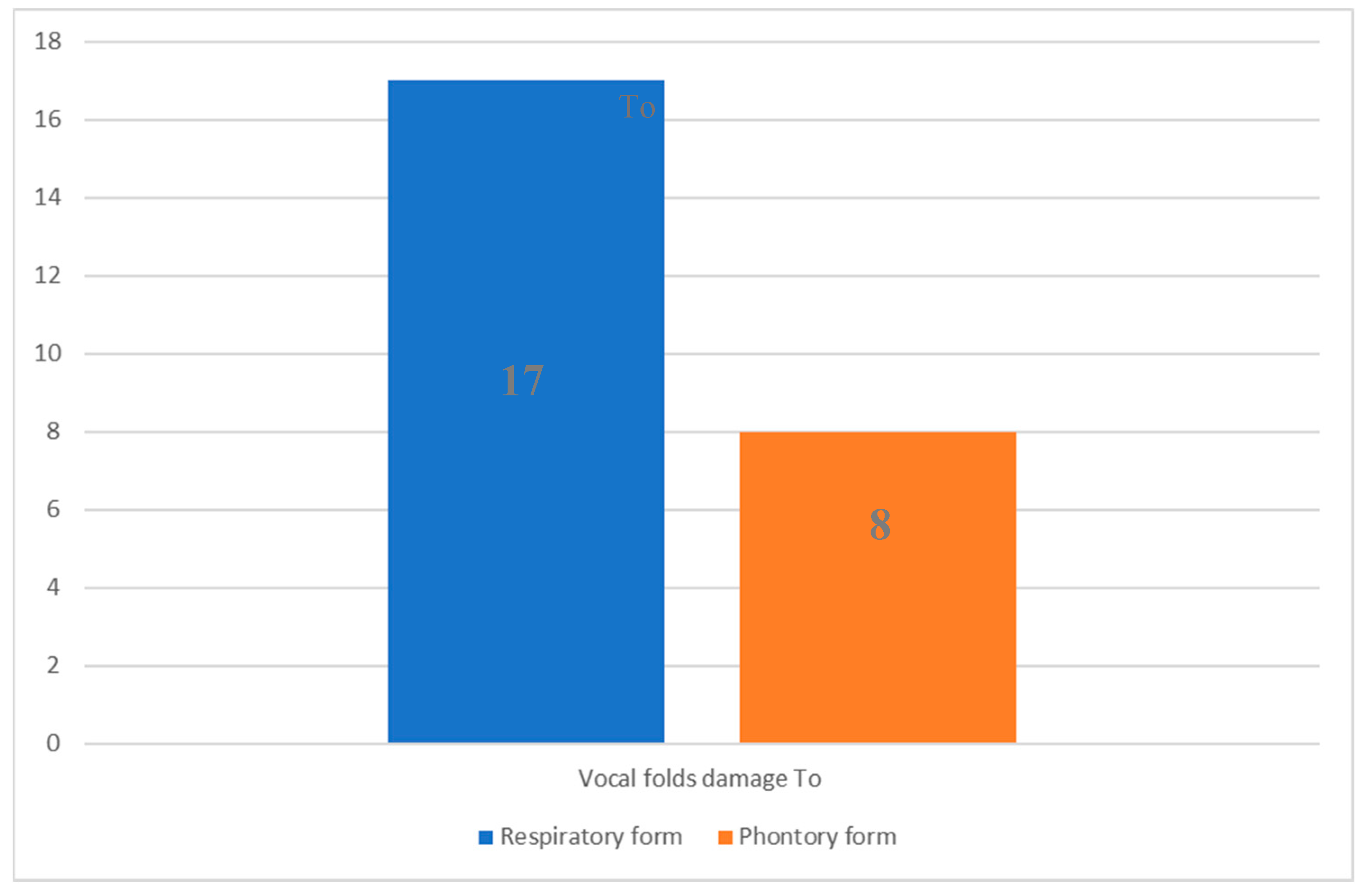

3. Results

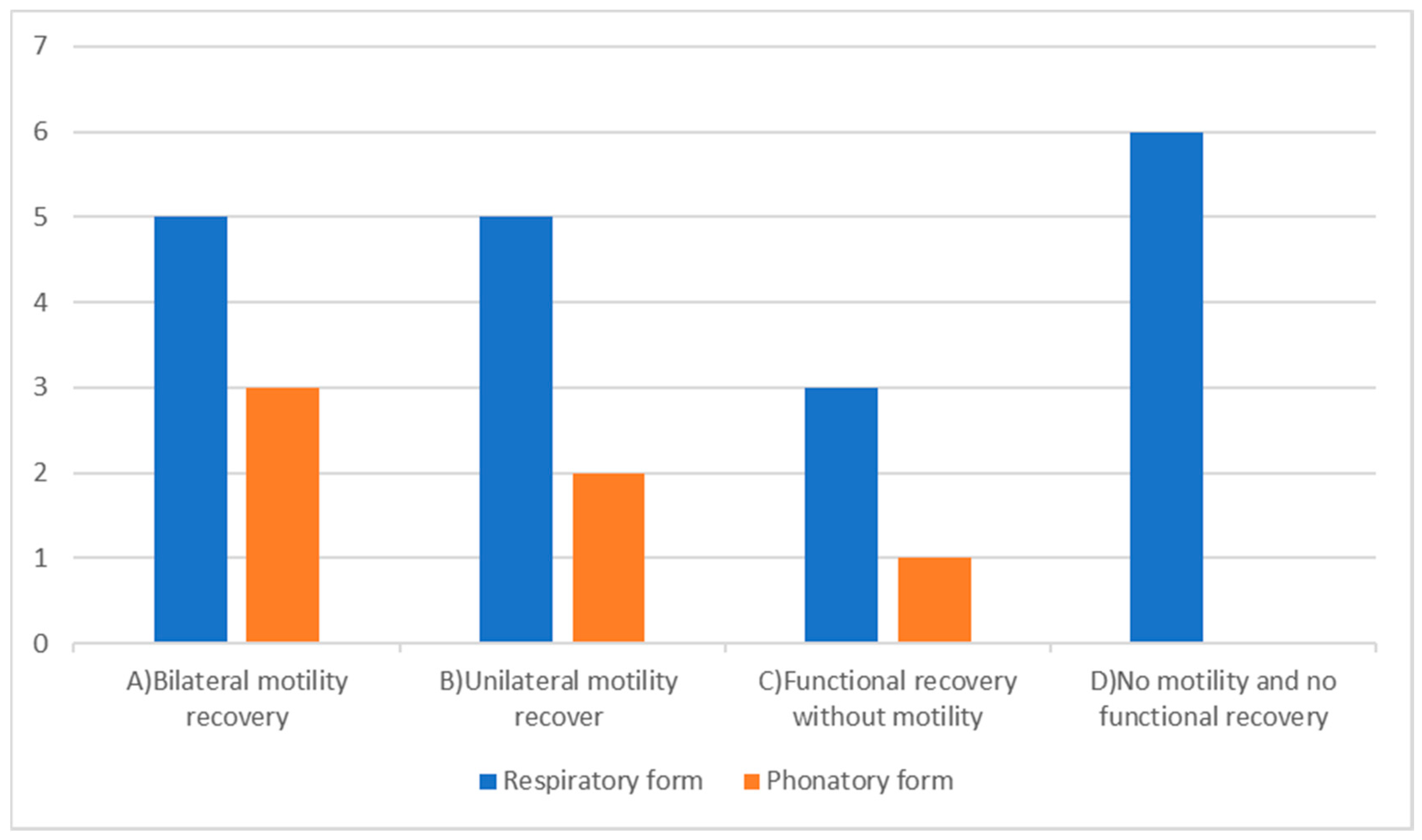

- Bilateral motility recovery occurred in 8 (32%) patients, 5 (20%) with the respiratory form and 3 (12%) with the phonatory one. The vocal fold motility restoration was achieved at a mean of 90 days (T1) after our assessment. In response to recovery patients concluded their voice therapy (Table 2-A);

- Unilateral mobility recovery occurred in 7 (28%) patients, 5 (20%) with the respiratory form and 2 (8%) with the phonatory form. The unilateral vocal fold motility restoration was obtained at a mean of 180 days (T2) after our evaluation; subjects continued voice therapy, as UVFP protocols, achieving good outcomes (Table 2-B);

4. Discussion

- Severe aerodynamic incoordination due to post-polio syndrome in one case [36]. However, this patient reached a good improvement in vocal and psychological aspects, attested by results at VHI scores and by the return to work;

- Allergies and asthmatic forms [39] in two cases;

- Depression [40] in one case;

- Multiple sclerosis [41] in one case.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christou N., Mathonnet M.: Rewiew: Complications after total thyroidectomy Journal of Visceral Surgery (2013) 150, 249—256. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar S.S, Randolph J.W. Seidman, M.D., Rosenfeld R. M.,Peter Angelos P., Barkmeier-Kraemer J.,Benninger M.S.,Blumin J.H., Gregory Dennis G., Hanks J., Haymart, M.R., Kloos R.T., Seals B., Schreibstein J.M.,Thomas, M.A.,Waddington C., Warren B., and Robertson P.J.: Clinical Practice Guideline: Improving Voice Outcomes after Thyroid Surgery. American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck, Surgery Foundation 2013 Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (2013)148(6S) S1– S37. [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, V., Motta, G., Tenore, G., Coletta, M., Guariglia, A., & Testa, D. (2018). The role of heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the oncogenesis of head and neck tumors and thyroid diseases: a pilot study. Biometals, 31(2), 285-295. [CrossRef]

- Rosato L., Miccoli P., Pinchera A., Lombardi G., Romano M., Avenia N., Bastagli A., Bellantone R., De Palma M., De Toma G., Gasparri G., Lampugnani R., Marini , Nasi P.G., Pelizzo M.R., Pezzullo L., Piccoli M, Testini M: Protocolli Gestionali Diagnostico-Terapeutico-Assistenziali in Chirurgia Tiroidea. 2ª Consensus Conference G Chir Vol. 30 - n. 3 - pp. 73-86 Marzo 2009.

- Pisello F., Geraci G., Sciumè C., Li Volsi F., Facella T., Modica G.,: Prevenzione delle complicanze in chirurgia tiroidea: la lesione del nervo laringeo ricorrente. Esperienza personale su 313 casi, Ann. Ital. Chir., LXXVI, 1, 2005.

- Ferraro F., Gambardella C., Testa D., Santini L., Marfella R., Fusco P., Lombardi CP., Polistena A., Sanguinetti A., Avenia N., Conzo G. Nasotracheal prolonged safe extubation in acute respiratory failure post-thyroidectomy: An efficacious technique to avoid tracheotomy? A retrospective analysis of a large case series. Int J Surg. 2017 May;41 Suppl 1: S48-S54. [CrossRef]

- Xuhui Chen, Ping Wan, Yabin Yu, Ming Li, Yanyan Xu, Ping Huang, and Zaoming Huang: Types and Timing of Therapy for Vocal Fold Paresis/Paralysis After Thyroidectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,Journal of Voice, Vol. 28, No. 6, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Joliat G.R., Guarnero V., Demartines N., Schweizer V., Matter M.:Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after thyroid and parathyroid surgery Incidence and postoperative evolution assessment Medicine (2017) 96:17(e6674). [CrossRef]

- Hayward N.J., Grodski S., Yeung M., Johnson W.R., and Serpell J.: Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in thyroid surgery: a review, ANZ J Surg 83 (2013) 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Higgins TS, Gupta R, Ketcham AS, Sataloff RT, Wadsworth JT, Sinacori JT. Recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring versus identification alone on post-thyroidectomy true vocal fold palsy: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2011; 121: 1009–17. [CrossRef]

- Dionigi G., Boni F., Rovera F., Rausei S., Castelnuovo P., Dionigi R. :Postoperative laryngoscopy in thyroid surgery: proper timing to detect recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, Langenbecks Arch Surg (2010) 395:327–331. [CrossRef]

- Li Y., Garrett G., Zealear D.: Current Treatment Options for Bilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis: A State-of-the-Art Review, Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology (2017) 10, 3: 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Testa D.,Guerra G., Landolfo P.G., Nunziata M.,Conzo G., Mesolella M., Motta G.: Current therapeutic prospectives in the functional rehabilitation of vocal fold paralysis after thyroidectomy: CO2 laser aritenoidectomy International Journal of Surgery (2014) 12 548-551. [CrossRef]

- Rubin A.D., Sataloff R.T.: Vocal Fold Paresis and Paralysis, Otolaryngol Clin N Am (2007) 401109–1131. [CrossRef]

- Motta S, Moscillo L, Imperiali M, Motta G.: CO2 laser treatment of bilateral vocal cord paralysis in adduction. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003 Nov-Dec;65(6):359-65. [CrossRef]

- Lawson G., Remacle M., Hamoir M., Jamart J: Posterior cordectomy and subtotal arytenoidectomy for the treatment of bilateral vocal fold immobility: Functional results, Journal of Voice Volume 10, Issue 3, 1996, 314-319. [CrossRef]

- Nawka T, Gugatschka M, Kölmel JC, Müller AH,Schneider-Stickler B, Yaremchuk S, Grosheva M, Hagen R, Maurer JT, Pototschnig C, Lehmann T, Volk GF, Guntinas-Lichius O: Therapy of bilateral vocal fold paralysis: real world data of an international multicenter registry, Published: April 29, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216096. [CrossRef]

- Muller A.H. Therapie von Rekurrensparesen, HNO June 2017, 65:621-630. [CrossRef]

- Susan Miller Voice therapy for vocal fold paralysis, Otolaryngol Clin N Am37 (2004) 105–119. [CrossRef]

- Schindler A., Bottero A., Capaccio P., Ginocchio D., Adorni F., and Ottaviani F. : Vocal Improvement After Voice Therapy in Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis, Journal of Voice, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Behrman A. Evidence-based treatment of paralytic dysphonia: making sense of outcomes and efficacy data. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 2004, 37 75–104. [CrossRef]

- Bartolini L., Luppi M.P., Benini M., Terenzi M. Terapia logopedica e fono chirurgia in Fonochirurgia endolaringea Quaderno monografico di aggiornamento A.O.O.I. Pacini Editore, Ospedaletto 1997, 181-197.

- Wing-Hei Viola Yu, Che-Wei Wu Speech therapy after thyroidectomy. Gland Surg 201, ;6(5):501-509. [CrossRef]

- Nawka, T., Sittel, C., Arens, C., Lang-Roth, R., Wittekindt, C., Hagen, R., Mueller, A. H., Nasr, A. I., Guntinas-Lichius, O., Fredrich, G. and Gugatschka, M. (2015), Voice and respiratory outcomes after permanent transoral surgery of bilateral vocal fold paralysis. The Laryngoscope, 125: 2749-2755. [CrossRef]

- Randolph GW. and Dralle H. with the International Intraoperative Monitoring Study Group. Electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: international standards guideline statement. Laryngoscope 2011; 121: S1-S16. [CrossRef]

- Dionigi G, et al. Why monitor the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery? J Endocrinal Invest. 2010; 33: 819-822. [CrossRef]

- Chiang FY, et al. Standardization of intraoperative neuromonitoring of recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid operation. World J Surg. 2010 Feb; 34 (2) : 223-9. [CrossRef]

- NICE 2017: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101/chapter/1-Guidance (23 February 2017, date last accessed).

- Gold 2011 (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Airways Disease): Jones PW., Adamek L., Nadeau G. et al: Comparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in COPD: implication for the Gold 2011 classification. Eur Respir J 2013; 42:647-654. [CrossRef]

- Bestall JC., Paul EA., Garrod R., Garnham R., Jones PW., Wedzicha JA. : Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999; 54: 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli R., Cocconcelli E., Lanini B., Romagnoli I., Florini F., Castaniere I., Andrisani D., Cerri S., Luppi F., Fantini R., Marchioni A., Beghè B., Gigliotti F. and Clini EM.: Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with interstitial lung disease of different etiology: a multicenter prospective study, Pulmonary Medicine (2017) 17:130 DOI 10.1186/s12890-017-0476-5. [CrossRef]

- Vagvolgyi A., Rozgonyi Z., Kerti M., Vadasz P., Varga J.: Effectiveness of perioperative pulmonary rehabilitation in thoracic surgery, J Thorac Dis 2017;9(6):1584-1591. [CrossRef]

- Longo L., De Vita R., Goretti P., Morelli M. : Paralisi ricorrenziali, valutazione e trattamento. L’utilizzo del VHI-test come indicatore dell’efficacia terapeutica, Prevent Res, published on line 05 Aug. 2013, P&R Public. 55. Available from: http://www.preventionandresearch.com/ . [CrossRef]

- Ricci Maccarini A., Lucchini E. : La valutazione soggettiva ed oggettiva della disfonia. Il protocollo SIFEL. Acta Phon Lat. 2002; 24(1–2):13–42.

- Salik I., Winters R. Bilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis. 2021 Jul 15. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 32809687.

- Orsini M., Lopes A.J., Guimarães F.S., Freitas M.R.G., Nascimento O.J.M., de Sant’ Anna JuniorM., Filho P.M., Fiorelli S., Ferreira A.C.A.F., Pupe C., BastosV.H.V., Pessoa B., Nogueira C.B., Schmidt B.,Souza O.G., Davidovich E.R., Oliveira A.S.B., Ribeiro P. Currents issues in cardiorespiratory care of patients with post-polio syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016, 74(7):574-579. [CrossRef]

- Littleton S.W. Impact of obesity on respiratory function. Respirology 2012, 17, 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Ling Ching-Kai and Ling Ching-Chi Work of breathing and respiratory drive in obesity. Respirology 2012, 17, 402–411. [CrossRef]

- Heffern WA., Davis TM., Ross CJ. A case study of comorbidities: vocal cord dysfunction, asthma and panic disorder. Clin Nurs Res. 2002 Aug; 11 (3):324-40. [CrossRef]

- Sardinha A., Freire RC, Zin WA, Nardi AE Respiratory manifestation of panic disorder: causes, consequences and therapeutic implication. J Bras Pneumol. 2009 Jul; 35 (7): 698-708. [CrossRef]

- Fry DK, Pfalzer LA, Chokshi AR, Wagner MT, Jackson ES Randomizzed control trial of effects of a 10-week inspiratory muscle training program on measures of pulmonary function in person with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007 Dec; 31 (4):162-72. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).