1. Introduction

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has posed an unprecedented burden to health-delivery systems globally. Since December 2019, COVID-19 has infected millions worldwide, dramatically forcing billions into social distancing [

1]. At an institutional level, the pandemic has disrupted outpatient care and elective surgeries, driving healthcare providers to quickly adapt to new guidelines on delivering care. A recent international survey in early 2020 and 2021 found that most general pediatric orthopedic surgeons paused all elective procedures, reported a decrease in average number of weekly surgeries and elective outpatient appointments, and increased usage of virtual modes of communication for the first time [

2].

Given that individualized, longitudinal, and intensive treatment is crucial to children with chronic complex conditions (CCC), COVID-19 has presented a tremendous, ongoing hurdle to their care. CCC is defined as any medical condition expected to last at least 12 months, involve at least one organ system requiring subspecialty care, and warrant hospitalization in a tertiary care center [

3]. Neuromuscular chronic complex conditions (NCCC)—one of 12 CCC categories—encompass cerebral palsy (CP), spina bifida, brain malformations, muscular dystrophy, and seizure disorders [

4]. Many patients with CP rely on frequent medical appointments and therapies to combat progressive muscle spasticity and contracture, in addition to orthopedic surveillance and surgical intervention to prevent progression of neuromuscular hip dysplasia.

While sparse, the extant literature suggests the COVID-19 pandemic has taken an exceptional toll on children with CP and their caregivers. Children with CP were found to have worse mobility, physical function, muscle cramps, pain, spasticity, and quality of life scores in the setting of delayed botulinum toxin administration, reduced therapies, and lack of access to support [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Caregivers reported decreased routine follow-up and physical rehabilitation sessions, with a significant decline in caregiver physical and mental quality of life [

6,

7,

9,

10]. Telerehabilitation and online-offline hybrid exercise programs have proven somewhat effective as temporizing measures, though limited in improving gross motor function, well-being, and reintegration to normal living in children with CP [

11,

12,

13].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate COVID-19-related challenges and modifications in healthcare practice, delivery, and resource utilization for children with NCCC. To our knowledge, this is the first international study surveying multidisciplinary pediatric practitioners of children with NCCC.

2. Materials and Methods

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, an electronic REDCap survey was administered between May and August 2020 to an international group of pediatric medical professionals who cared for children with NCCC [

14,

15]. The survey was distributed using national list-serves, Twitter, and national society chat rooms among members of the American Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM) and other international academic medical networks utilized by the Cerebral Palsy Center at our institution. Inclusion criteria included English-speaking medical professionals (MD, NP, RN, PA, PT, OT, etc.) associated with AACPDM who treat patients with CP and were currently practicing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adapted from a prior questionnaire created by Gibbard et al. for general pediatric orthopedic surgeons [

2], our current survey comprised open- and closed-ended questions on provider demographics, clinical background, pediatric neuromuscular care before and during the pandemic, and clinic/hospital guidelines for procedures and orthopedic surgeries. Provider demographic and clinical data were described in tabular form. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square analysis was utilized to determine if there were any differences in visit options before COVID and during COVID. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Thematic analysis was used for qualitative responses.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

A total of 79 responses were received between May and August 2020 from providers across 8 countries (

Table 1). Respondents were primarily pediatric orthopedic surgeons (25/79, 32%), pediatricians (24/79, 30%), and pediatric physiatrists (18/79, 23%), and 66% had over 10 years of experience since graduating from residency/professional training (50/76). Most were 100% pediatrics-based (62/77, 81%) with a significant focus on neuromuscular disease (54/77, 70%). Over half of all providers, regardless of medical profession, completed more advanced “fellowship” training covering care for children with NCCC, such as pediatric orthopedics, pediatric rehabilitation medicine, neurodevelopmental disabilities, and pediatric complex care (45/77, 58%).

3.2. Clinical Practice

Most respondents (47/79, 59%) felt it was especially difficult to provide effective care to children with NCCC during the pandemic, though a minority (31/79, 39%) reported it was equally as difficult to treat both NCCC and non-NCCC patients alike. Fewer (21/78, 27%) felt the pandemic affected their ability to provide urgent and emergent care for children with NCCC. Given that all elective procedures were almost universally stopped by the time of survey, most providers decided to take a break and resume treatment once the pandemic eased and elective cases were permitted again (51/72, 71%), while 24% opted to book these cases as “semi-urgent” and requested special permission from hospital administration on a case-by-case basis (17/72).

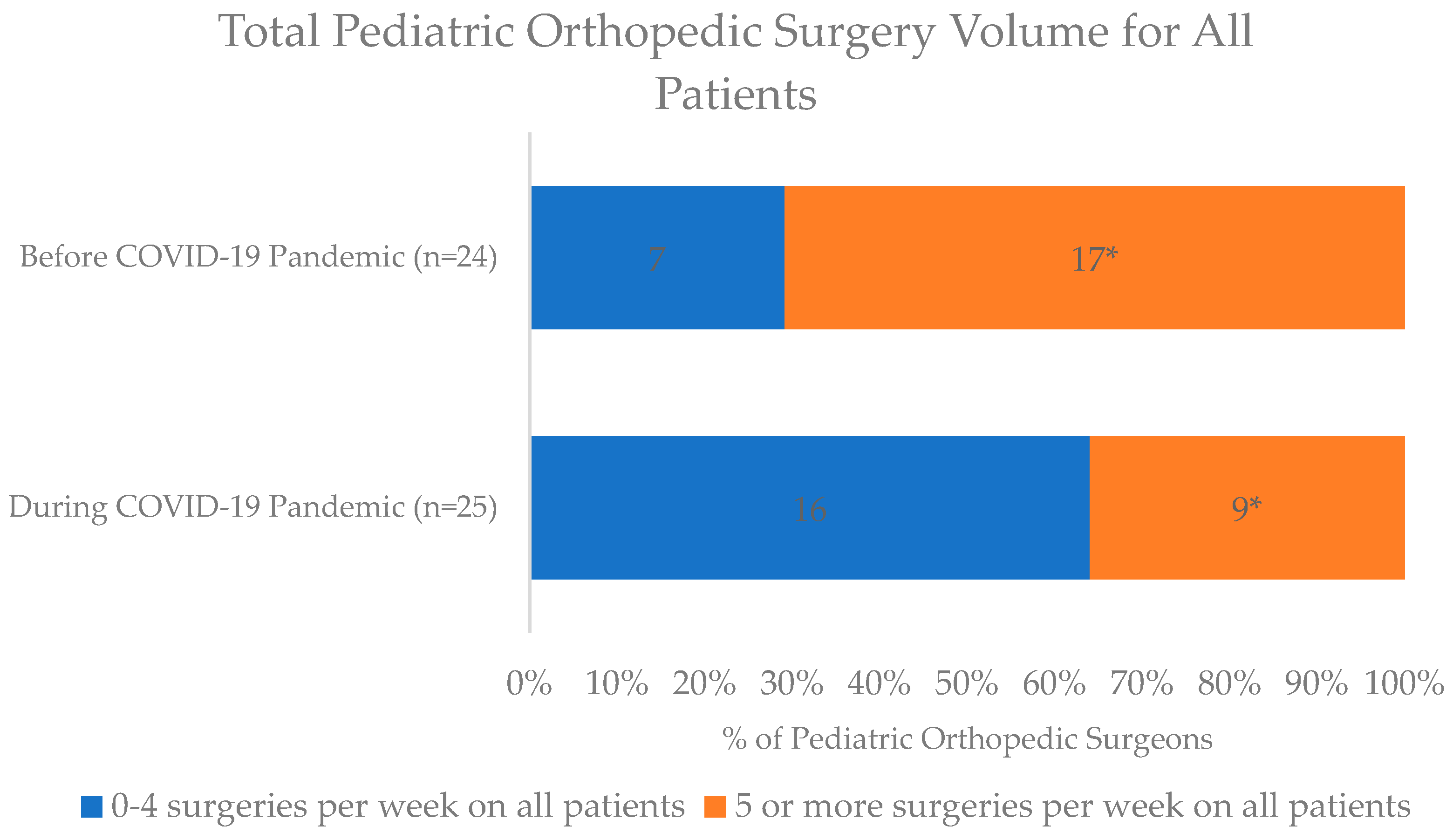

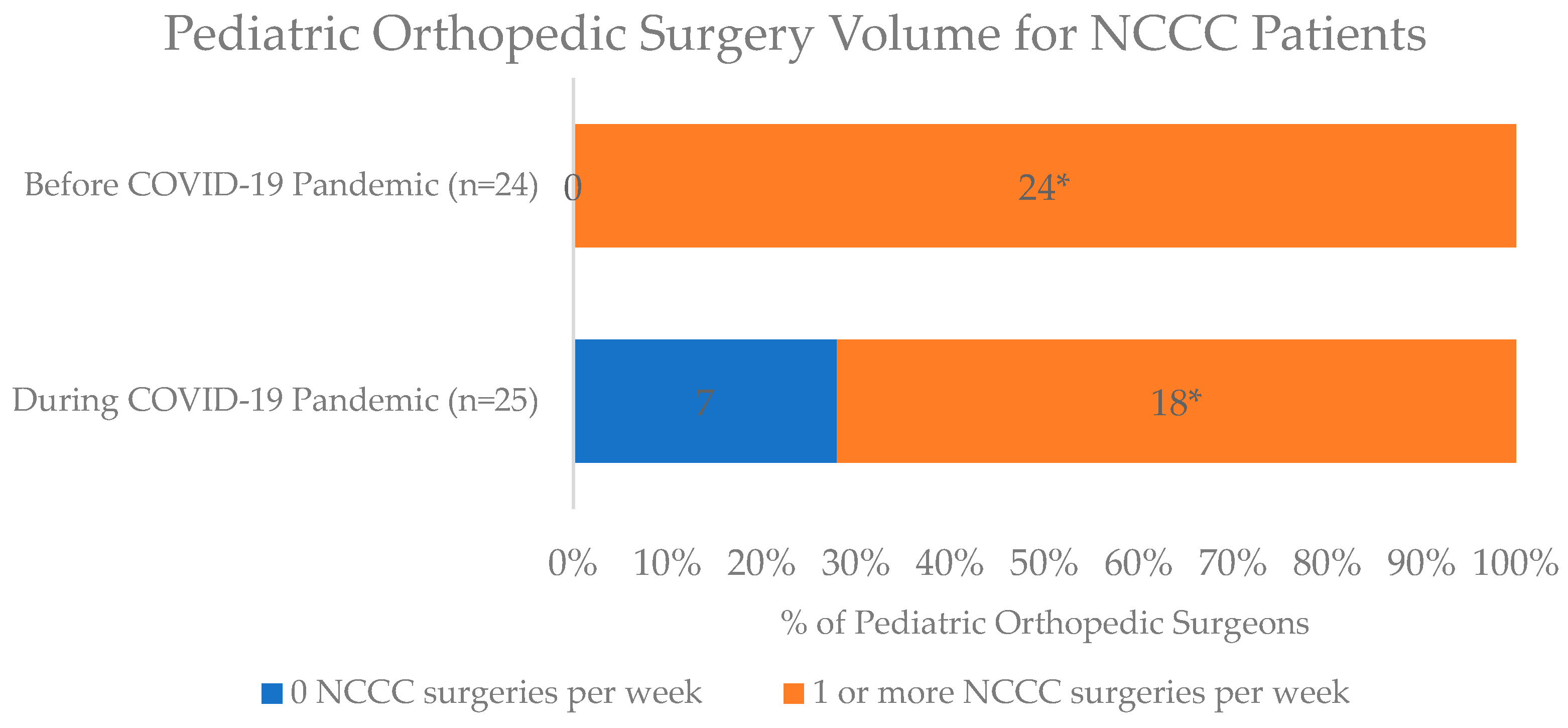

For surgical care, most respondents were aware that elective surgeries at their respective institutions had been deferred since March 2020 (73/77, 95%). Among pediatric orthopedic surgeons (n=25), 68% (17/25) were performing both elective and urgent/emergent procedures, 28% (7/25) were performing only urgent/emergent procedures, and only 4% (1/25) were exclusively performing elective procedures during the pandemic—compared to before the pandemic, when most 83% (20/24, 83%) were exclusively elective and 17% (4/24) did urgent/emergent procedures. A significantly lower percentage of orthopedic surgeons reported performing at least 5 surgeries per week on all patients at the peak of the pandemic in April 2020 (36%, 9/25) relative to prior to the pandemic (17/24, 71%; p=0.01). Furthermore, while all (100%, 24/24) orthopedic surgeons performed at least one surgery on NCCC patients per week prior to the pandemic, only 72% (18/25) continued at this rate during the pandemic (p=0.005), with 7 orthopedic surgeons completely stopping surgeries for NCCC patients altogether (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

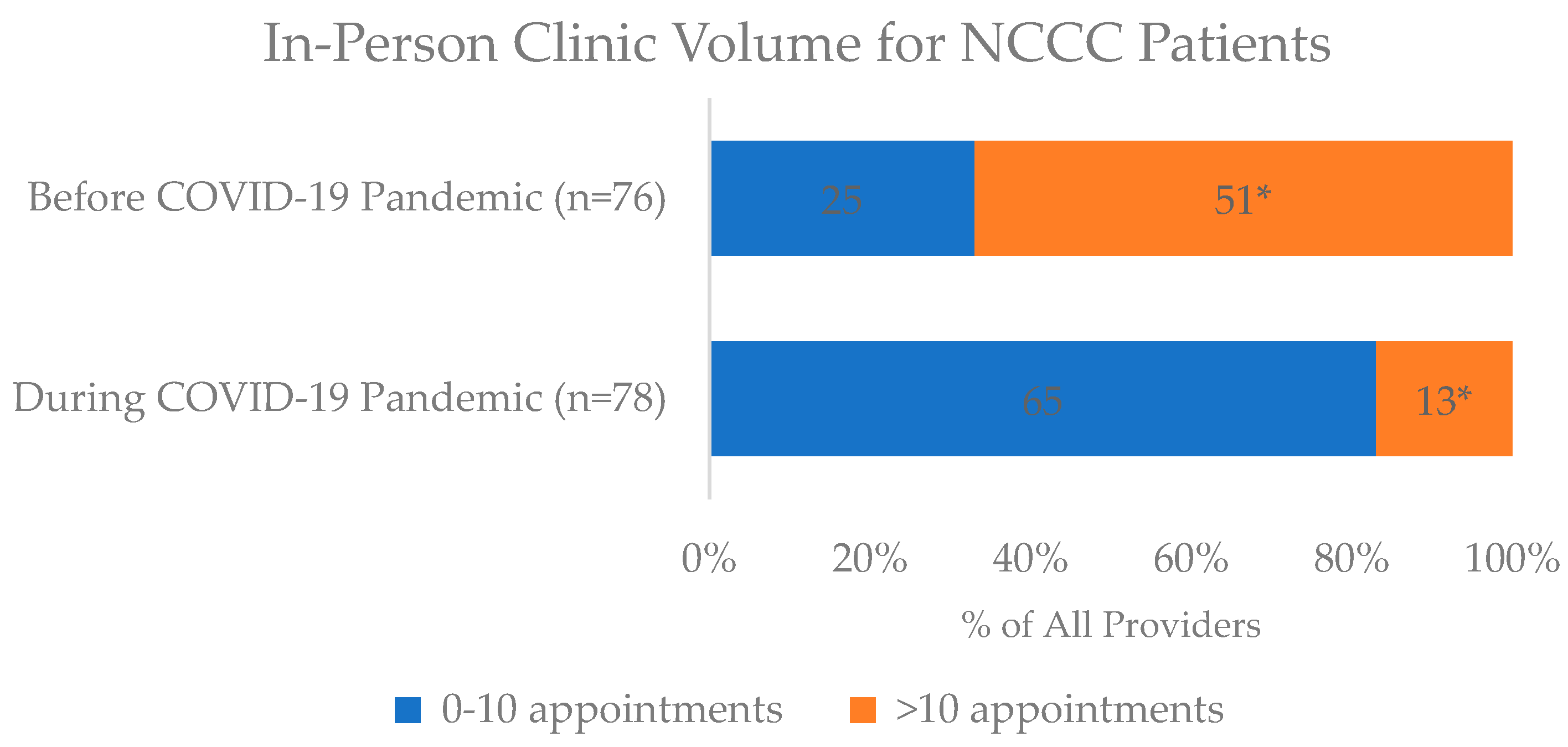

For outpatient care, many providers reported routine clinic appointments also stopped across all hospital and clinic settings (64/78, 82%) by mid-April 2020. At the height of the pandemic, most providers (44/79, 56%) did not continue to see NCCC patients in person. There was a sharp decrease in providers who had more than 10 in-person NCCC clinic appointments per week from before the pandemic (51/76, 67%) to during the pandemic (13/78, 17%; p<0.001) (

Figure 3). Additionally, only 18% (14/77) continued in-person multidisciplinary appointments during the pandemic compared to 82% (62/76) prior to COVID (p<0.001). About half (38/79, 48%) reported their patients were no longer receiving in-person physical or occupational therapy, though most (70/78, 90%) said patients were still receiving some therapy (e.g., speech) via telehealth.

In March 2020 of the pandemic, 63% (22/35) and 84% (27/32) of providers stopped administering botulinum toxin/phenol injections in the clinic and operating room, respectively, with expected date of resumption 2-4 months later. Reassuringly, braces continued to be modified (56/76, 74%) generally in the following settings: hospital/clinic-based orthotic clinic, private orthotics office, orthotic house call, or other.

3.3. Employer and Professional Society Guidelines

At the time of survey, almost all providers (71/77, 92%) said their workplace had an Emergency Operations Center/COVID-19 Task Force disseminating daily COVID-19 updates (61/76, 80%) and received guidance from their national professional society (64/76, 84%). A majority (65/73, 89%) indicated their respective hospitals provided guidelines regarding emergency and elective surgeries on COVID-positive patients. Nearly all (71/74, 96%) reported that hospitals were routinely screening patients prior to surgery, personal protective equipment (PPE) was provided by their institutions (68/74, 92%), clinicians were not expected to procure PPE at their own cost (73/77, 95%), and they were not recruited to assist in non-subspecialty trained care in the intensive care unit or emergency department (ED) (69/79, 87%).

While nearly everyone (70/77, 91%) had to rearrange their work practice (e.g., limited physical contact, no x-rays), most (47/77, 61%) were not required to go to the hospital every day during the pandemic. About half (40/76, 53%) of hospitals/clinics had back-up personnel to perform duties in case providers were sick, with teams to provide on-call services (39/65, 60%).

3.4. Technology

Prior to the pandemic, most providers had never used telemedicine for patient appointments (51/75, 68%) due to lack of hospital/clinic approval (26/49, 53%), unavailability (8/49, 16%), provider preference (7/49, 14%), patient preference (1/49, 2%), or other reasons (7/49, 14%). During the pandemic, almost all providers (75/78, 96%) adopted virtual clinical platforms, which was significantly higher than prior (22/75, 29%; p<0.001). Most providers reported their medical council/state licensure relaxed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance for the duration of the pandemic (43/79, 54%), and many (43/74, 58%) saw virtual patients in additional jurisdictions as a result. Almost all providers stated that virtual visits were permitted by their medical council/state legislature (74/78, 95%).

Popular types of NCCC telemedicine appointments during the pandemic were follow-ups (72/75, 96%) and new patient visits (41/75, 55%). Post-operative (28/75, 37%), gait lab/tests results review (19/75, 25%), and other visit types (6/75, 8%) were less common. Most providers were able to hold multidisciplinary appointments virtually (46/75, 61%). Of those utilizing telemedicine during the pandemic, 74% had 10 or fewer virtual visits per week (54/73), while just 26% of providers (19/73) had greater than 10 visits weekly. Although more than half (40/73, 55%) were not able to provide scanned written prescriptions during virtual visits, nearly everyone (67/74, 91%) expressed being able to bill. Of those who said they were able to bill, just over half were able to charge the same amount as in-person visits (34/67, 51%), while 28% were billed for less (19/67, 28%), and others did not know (14/67, 21%).

Challenges were frequently encountered when assessing NCCC patients via telehealth (51/73, 70%), especially with the physical exam, which was acceptable for general assessments (incisions, overall appearance) but more limited for spasticity, tone, strength, range of motion, gait, orthotic fit, anthropometrics, and subtle findings in conditions such as scoliosis and hip dysplasia. Thematic analyses of participant qualitative responses revealed that providers had to draw from patient, family, and caregiver participation to assist with the physical exam, which was less reliable and feasible. Some providers even sent patients to the ED for in-person exams regarding issues otherwise appropriate for outpatient.

Many providers also highlighted communication struggles with patients and families over virtual visits. Relying on families to report patient progress can be less accurate than in-person observation, and verbally explaining how to perform certain exam maneuvers virtually can be unwieldy. An even greater burden was placed on families requiring interpreters.

Another theme among the qualitative data was the challenge of finding a proper setting for telehealth/virtual visits. It was arduous for families and patients to access quiet, private locations without distractions. For patients necessitating imaging, providers had to either forgo or separately coordinate radiology visits if possible. A final common obstacle was the technology itself, which was often slow and cumbersome, increasing fatigue for both parents and providers. Learning the skills to be technologically savvy and acquiring adequate electronic resources/equipment (e.g., laptop, cellphone), internet, and video/audio quality were barriers. For providers, virtual visits were sometimes reported to be less efficient and demanded more time/energy spent on navigating technology, as well as reviewing and documenting supplemental media.

3.5. Provider Connection and Wellness

Most providers (73/78, 94%) continued formal meetings with colleagues during the pandemic using mostly video calls—sometimes phone calls—on Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Skype, and other platforms (e.g., Webex, BlueJeans, Attend Everywhere). Staff wellness activities were implemented at most hospitals, including chaplain “check-ins,” peer-led counseling, free food, mindfulness, and compassion rounds (48/76, 63%). The majority felt their administration cared about their well-being (68/76, 89%) and felt safe at work (67/77, 87%).

4. Discussion

The multidisciplinary, collaborative nature of caring for children with NCCC makes the restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic particularly problematic. At the beginning of the pandemic, significant changes to healthcare delivery led to negative outcomes for children with NCCC and their caregivers, as reported in prior studies [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Now, documenting the perspective of their providers, our study results support these findings, with most providers acknowledging it was inordinately more difficult to care for this patient population during the pandemic.

Institutional and regional regulations, such as restrictions on elective procedures and in-person clinic visits, in addition to concerns about contracting COVID-19, were common challenges. Given these newfound obstacles, nearly all providers adopted a telemedicine platform. Despite its shortcomings, telemedicine played a large role in ensuring continuity of care for NCCC patients outside of standard settings. Though unable to completely substitute face-to-face clinic visits, telemedicine can be strategically used as an adjunct to in-person clinical visits. If the focus on telemedicine continues, we recommend additional development and validation of components of the physical exam which can be completed on a telemedicine platform (e.g., gait, range of motion, scoliosis, etc). Informational videos and documents are needed for providers and parents/patients to improve the telemedicine visit utility. Patients and families should also be asked about their proficiency in and access to technological equipment, and be referred for adequate assistance if deemed disadvantaged or lower-resourced. As the care for children with NCCC requires a unique and more nuanced approach, this needs assessment should be made a priority to optimize the value of each telemedicine appointment.

The strengths of this study are twofold: informing future best practice guidelines in the setting of future pandemics and highlighting areas for continued investigation/improvement. Given that scientists estimate approximately 1.7 million undiscovered viruses, there is risk for another deadly, easily transmissible pathogen [

16]. The new monkeypox outbreak of 2022-2023 is one such example [

17]. To avoid repeating similar disruptions in healthcare delivery, steps can be taken now to mold resilient systems that facilitate continuity of care for children with NCCC. Applying the science of quality improvement (e.g., plan-do-study-act cycles) to the pressurized circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic can ensure a methodical, sensitive, and pragmatic approach for tackling procedural and structural changes [

18,

19]. For patients sustaining unexpected setbacks during COVID-19, the medical community has a duty to ensure these children are given opportunities to thrive in this new norm. These lessons can also be applied to children with other CCC, as well as to lower-resource settings vulnerable to these disruptions.

This study is not without limitations. Recall and selection biases are inherent in self-reported responses. Additionally, though this survey intended to gather international experiences, having few responses outside of the United States limits generalizability. Furthermore, many advances in COVID-19 response/treatment have been made since the study data were collected in 2020, warranting a more updated look; however, capturing the same respondents at a second time point was not feasible for this study. Finally, while our study demonstrated most providers had access to staff wellness programs, it is unclear how these have influenced morale, mental health, and performance. Provider burnout, amplified during the pandemic, impacts both occupational workers and patients, with recent reviews suggesting a link between physician burnout and negative outcomes for patient care, such as increased medical errors [

20]. Additional exploration to promote a healthier work environment will ultimately improve the quality of care delivered to children with NCCC during these stressors.

5. Conclusions

Our study revealed that practices across multiple disciplines suffered during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, with providers perceiving that suboptimal care for children with CP and NCCC transpired. As we transition to living with the reality that similar pandemics are possible, rigorously examining and understanding the barriers from COVID-19 can inform the development of sustainable solutions to prevent our healthcare system from coming to a halt again and improving the overall care of children with NCCC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and B.S.; methodology, B.S. and D.C.; validation, H.N. and D.C.; formal analysis, D.C.; resources, B.S.; data curation, H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.; writing—review and editing, H.N., N.M., D.C., M.G., W.S., R.S., K.M., and B.S.; visualization, H.N.; supervision, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Boston Children’s Hospital (IRB-P00035668 and date of approval May 21, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johns Hopkins University C for SS and, E. Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV). COVID-19 Dashboard 2022. Available online: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Gibbard, M.; Ponton, E.; Sidhu, B.V.; Farrell, S.; Bone, J.N.; Wu, L.A.; et al. Survey of the impact of COVID-19 on pediatric orthopaedic surgeons globally. J Pediatr Orthop 2021, 41, E692–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feudtner, C.; Christakis, D.A. ACF Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997 - PubMed. Pediatrics 2000. (accessed , 2022). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10888693/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Shore, B.J.; Hall, M.; Matheney, T.H.; Snyder, B.; Trenor, C.C.; Berry, J.G. Incidence of Pediatric Venous Thromboembolism After Elective Spine and Lower-Extremity Surgery in Children With Neuromuscular Complex Chronic Conditions: Do we Need Prophylaxis? J Pediatr Orthop 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogruoz Karatekin, B.; İcagasioglu, A.; Sahin, S.N.; Kacar, G.; Bayram, F. How Did the Lockdown Imposed Due to COVID-19 Affect Patients With Cerebral Palsy? Pediatr Phys Ther 2021, 33, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino, D.; Gnasso, R.; Migliore, F.; Iommazzo, I.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic countermeasures on patients receiving botulinum toxin therapy and on their caregivers: a study from an Italian cohort. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 3071–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, E.N.; Francis, L.S.; Francis, S.M.; Lench, D.H.; Nemanich, S.T.; Krach, L.E.; et al. Disrupted Access to Therapies and Impact on Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic for Children With Motor Impairment and Their Caregivers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2021, 100, 821–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, A.R.; Gad, M.V.; Rathod, C.M. Impact of COVID Pandemic on the Children with Cerebral Palsy. Indian J Orthop 2022, 56, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cankurtaran, D.; Tezel, N.; Yildiz, S.Y.; Celik, G.; Unlu Akyuz, E. Evaluation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with cerebral palsy, caregivers’ quality of life, and caregivers’ fear of COVID-19 with telemedicine. Ir J Med Sci 2021, 190, 1473–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P A, I A, F UO, A A, M YK, K C. Rehabilitation status of children with cerebral palsy and anxiety of their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. North Clin Istanbul 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Cristinziano, M.; Assenza, C.; Antenore, C.; Pellicciari, L.; Foti, C.; Morelli, D. Telerehabilitation during Covid-19 lockdown and gross motor function in cerebral palsy: an observational study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.; Han, A.; Lee, M.; Kim, M. The Effects of an Online-Offline Hybrid Exercise Program on the Lives of Children with Cerebral Palsy Using Wheelchairs during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarti, D.; De Salvatore, M.; Pagliano, E.; Granocchio, E.; Traficante, D.; Lombardi, E. Telerehabilitation and Wellbeing Experience in Children with Special Needs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Child (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009, 42, 377–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brulliard, K. The next pandemic is already coming, unless humans change how we interact with wildlife, scientists say - The Washington Post. Washington Post 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2020/04/03/coronavirus-wildlife-environment/#comments-wrapper (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s statement at the press conference following IHR Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox - 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-the-press-conference-following-IHR-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi--country-outbreak-of-monkeypox--23-july-2022 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Mondoux, S.; Thull-Freedman, J.; Dowling, S.; Gardner, K.; Taher, A.; Gupta, R.; et al. Quality improvement in the time of coronavirus disease 2019 – A change strategy well suited to pandemic response. CJEM 2020, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Pereira, P.; Tuma, P. Quality improvement at times of crisis. BMJ 2021, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangory, K.Y.; Ali, L.Y.; Rø, K.I.; Tyssen, R. Effect of burnout among physicians on observed adverse patient outcomes: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).