1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an epidemic disease associated with severe respiratory syndromes, and in 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a global public health emergency (Stasi, Fallani, Voller, & Silvestri, 2020). To curb the spread of the COVID-19 virus, social distancing measures were implemented worldwide during the pandemic, leading to the closure of schools and public facilities and limiting non-essential gatherings (Dawson, Ashcroft, Lorenz-Dant, & Comas-Herrera, 2020; E.-A. Kim, 2020; H. Kim, 2020).

Despite their effectiveness in reducing virus transmission, these necessary measures have unintended health-related consequences for children and adolescents. Specifically, the restrictions have resulted in decreased participation in physical activity (PA) (Bates et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2020; Zenic et al., 2020), increased sedentary behavior (SB) (Bates et al., 2020; Margaritis et al., 2020; Vanderloo et al., 2020), and disrupted sleep patterns (Bates et al., 2020; Becker & Gregory, 2020; J. Lee, 2020) among the youth. Such reductions in PA and increased SB carry significant risks for the long-term health of young individuals, potentially contributing to the development of various chronic diseases that may persist into adulthood (Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2008). In light of these concerns, the WHO issued guidelines in 2020, recommending that children and adolescents engage in a minimum of 60 minutes or more of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) daily, including regular aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities at least three days a week (Chaput et al., 2020). Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent restrictions have limited the opportunities for youth to engage in PA-related activities (Schmidt et al., 2020).

In addition to its direct impact on the youth’s health, the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent restrictions have had a substantial effect on families’ socioeconomic status (SES), including the economic crisis, income loss, and unemployment (Dang & Nguyen, 2021). These socioeconomic changes are indirectly associated with the health-related behaviors of the youth (Buzek et al., 2019; Reiss et al., 2019). Extensive research has consistently demonstrated significant associations between family SES and health-related behaviors among youth individuals. Studies have revealed that adolescents from high-income families tend to engage in more MVPA and experience lower levels of inactivity compared to counterparts from low-income families (Bauman et al., 2012; Bauman, Sallis, Dzewaltowski, & Owen, 2002; Gordon-Larsen, McMurray, & Popkin, 2000). Conversely, research has indicated that children from low SES families face a higher risk of various health-related issues, such as sleep deficiency, overweight, academic stress, and other mental health problems (Bagley & El-Sheikh, 2013; Buzek et al., 2019; Hassan, Davis, & Chervin, 2011; Reiss et al., 2019). Additionally, several studies have emphasized the significant association between parental support and youth’s engagement in PA (Rhodes & Lim, 2018; Rhodes et al., 2019; Yun et al., 2018). Considering this existing evidence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 may influence children’s daily PA, possibly mediated by parental support (Moore et al., 2020).

In light of the importance of exploring the interplay between external factors, family processes, and children’s perceptions (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010; Goodenow, 1993), it becomes essential to consider the impact of COVID-19 on family SES and how it may have influenced children’s perception of their family’s SES, irrespective of the actual family SES. Thus, alongside actual family SES, gaining insight into children’s perception of their family SES becomes imperative to fully comprehend the multifaceted relationship between socioeconomic factors and health-related behaviors in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the associations between PA, SB, and perceived stress among Korean adolescents. Specifically, we aim to focus on changes in the perception of family SES during the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, a period characterized by widespread implementation of social distancing measures and restrictions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The KYRBS is a cross-sectional survey that was initiated in 2005 by the Korean Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCP). The survey is designed to evaluate the risk of health-related behaviors in 15 areas (e.g., SES, PA, and mental health) among youths in South Korea. The validity and reliability of KYRBS’s questionnaire have been demonstrated in previous studies (Bae et al., 2010). In this study, we assessed the variables of PA, SB, stress, and perception of changes in SES were assessed in adolescents aged 12–18 years who agreed to participate in the 16th year (2020) of the KYRBS. Since this survey is an online anonymous survey that does not collect any personal information of the participants, it was not necessary to obtain ethical approval from an institutional review board (IRB). The data of KYRBS is the government-approved statistical survey (No. 117058) based on Article 18 of the Statistical Act of the Republic of Korea.

2.2. Study participants

A total of 57,925 Korean adolescents from 800 schools (400 from middle schools and 400 from high schools) responded to the 2020 KYRBS survey. After excluding adolescents who did not respond and missing data, the final sample consisted of 54,948 participants. The current study divided the participants into two groups: those who responded that their family’s SES had been lower after COVID-19 (Lower SES; n = 3072) and those who responded that their family’s SES did not change (Non-changed = 3072). To ensure that the two groups were comparable, participants who responded that their family’s SES did not change were matched in age, gender, and BMI to the Lower SES group. Therefore, a total of 6144 participants were included in this study.

Table 1 summarizes the participants’ demographic information. The study participants consisted of 54.9% of boys and 45.1% of girls who were in middle school or high school. The participants’ anthropometric information was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The mean height, weight, and BMI for boys were 171.24 ± 7.84 cm, 65.80 ± 13.78 kg, and 22.33 ± 3.91 kg·m

-2, respectively, and the mean height, weight, and BMI for girls were 161.10 ± 5.38 cm, 53.86 ± 9.42 kg, and 20.72 ± 3.22 kg·m

-2, respectively. The results of the independent

t-test showed no significant differences in height, weight, and BMI between the two groups (

p > 0.05). The Low SES group had a higher percentage of individuals with academic performance in the low to middle level (67.5%), whereas the Non-changed SES group had more individuals in the middle to high level (77.1%). Additionally, the Lower SES group had a larger population of individuals in the low to middle classes of actual family SES (73.9%), while the Non-changed SES group had a higher representation in the middle to high classes (95.9%). A detailed description is presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Measures

Physical Activity. The daily PA was assessed using the following questions from the KYRBS; Total PA was asked as “How many days do you usually do a total of 60 minutes or more of moderate-intensity PA (any type) for a week?”. An 8-point scale (i.e., 1 = Never, 2 = 1 day, 3 = 2 days, 4 = 3 days, 5 = 4 days, 6 = 5 days, 7 = 6 days, and 8 = every day) was added to the former question. The VPA and muscular strength activities were asked as “How many days do you usually do 20 minutes or more of VPA (i.e., jogging, playing soccer, basketball, taekwondo, mountain climbing, riding a bicycle or swimming at high speed, and carrying heavy objects) for a week?”, and “How many days do you usually do muscular strength activities (i.e., push-ups, sit-ups, lifting weights, dumbbells, chin-up bar, and parallel bar) for a week?”. Further, a 6-point scale (i.e., 1 = Never, 2 = 1 day, 3 = 2 days, 4 = 3 days, 5 = 4 days, and 6 = More than 5 days) was added to the former questions. The participants were grouped into 3 categories based on the number of days of participation in PA: an active group (> 3 days (4–7 days)), a normal active group (≤ 3 days (2–3 days)), and an inactive group (≤ 1 day (0–1 day)).

Sedentary Behavior. The SB variable was assessed by asking the following question; “How many hours do you usually sit in a day (i.e., sitting at a desk for studying or doing assignments, sitting with friends, moving by car, bus, or train, reading a book, writing, playing a card game, watching TV, playing a video/computer game, and using the Internet)?”. The SB was calculated as the amount of sitting time (minutes per week). The participants were grouped into 3 categories based on their weekly sitting time (i.e., High SB (≥ 1380 minutes), Medium SB (920–1379 minutes), and Low SB (< 920 minutes)) for comparing differences in SB levels.

Stress. The perception of stress was assessed through the following question; “How much stress do you usually feel in your daily life?”. A 5-point Likert Scale (i.e., 1 = Very Severe, 2 = Severe, 3 = Moderate, 4 = Mild, and 5 = Very Mild) was used for the perceived stress question.

Data analysis. All data obtained in this study were summarized by SPSS 26.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The participant’s personal information (i.e., age, education, and socio-economic status) was examined by descriptive statistics, and anthropometrics information (i.e., height, weight, and BMI) were analyzed by an independent t-test to investigate the differences between the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group. Multinominal logistic regression was used to predict the impact of perception of family SES on the PA, SB, and stress variables comparing the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group by adjusting actual family SES and participants’ academic performance, which is measured categorically as responded by high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, and low. The results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Additionally, we conducted a comparative analysis by presenting average participation days in PA, the time spent in SB per week, and stress levels between the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group. All statistical significances were set by p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 2 presents the findings of multinomial logistic regression analysis investigating the influence of family SES perception on PA, SB, and stress levels while adjusting for actual family SES and participants’ academic performance. The results reveal notable differences between the Lower SES group and the Non-changed group. Regarding PA, adolescents who perceived a lower family SES during COVID-19 were 1.40 times more likely to engage in VPA for less than 1 day (OR = 1.40; CI = 1.14–1.73;

p = 0.001) and 1.3 times more likely to do so for less than 3 days (OR = 1.30; CI = 1.11–1.51;

p < 0.001) compared to the Non-changed SES group. Similarly, for muscular strength activities, the odds of participation for less than 1 day (OR = 1.38; CI = 1.15–1.67;

p < 0.01) and less than 3 days (OR = 1.31; CI = 1.11–1.54;

p = 0.001) were higher in the lower SES group. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in participating in total PA less than 1 day (OR = 0.90; CI = 0.74–1.09;

p > 0.05) and less than 3 days (OR =0.99; CI = 0.86–1.13;

p > 0.05). Regarding SB, there were significant differences between the two groups. Adolescents in the Lower SES group had a 33 % lower likelihood of being classified as High SB (OR = 0.67; CI = 0.58–0.77;

p < 0.001) and a 21% lower likelihood of being categorized as Medium SB (OR = 0.79; CI = 0.68–0.91;

p < 0.001) compared to the Non-changed SES group. Concerning stress levels, adolescents in the Lower SES group were 2.3 times more likely to experience a very severe level of stress (OR = 2.27; CI = 1.67–3.09;

p < 0.001) and 41% less likely to experience mild-level of stress (OR = 0.59; CI = 0.44–0.78;

p < 0.001) than their counterparts in the Non-changed SES group.

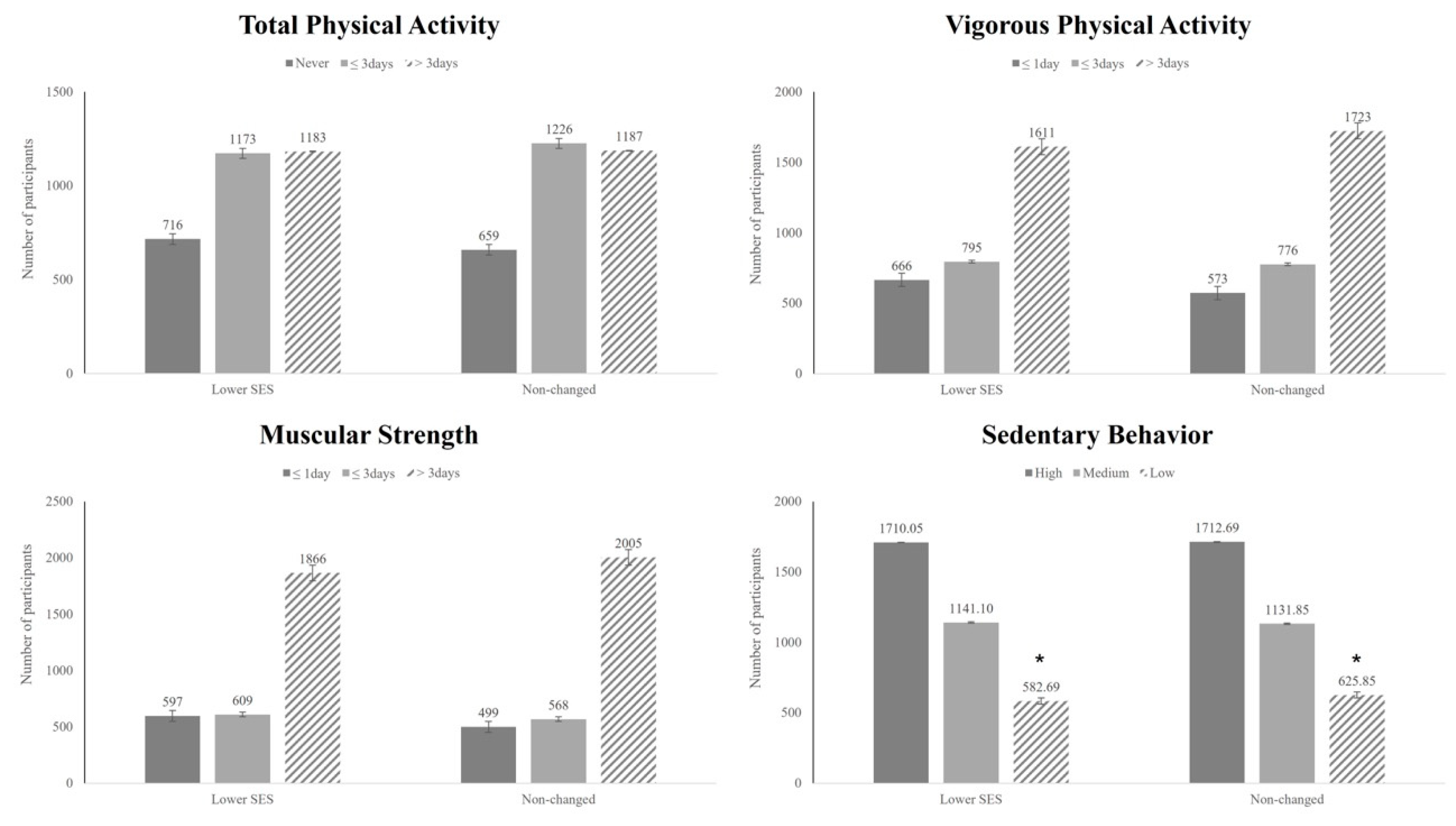

Figure 1 presents the comparative analysis of average participation days in PA and the time spent in SB per week between the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group. In the Lower SES group, 1610 individuals participated in total PA for 1 day or less per week, 746 individuals participated for 3 days or less per week, 746 individuals participated for 3 days or less per week, and 716 individuals participated for more than 3 days per week. In contrast, the Non-changed SES group had 1641 participants engaging in total PA for 1 day or less per week, 772 participants for 3 days or less per week, and 659 participants for more than 3 days per week. for total PA. Regarding VPA, the Lower SES group had 666 individuals participating for 1 day or less per week, 795 individuals for 3 days or less per week, and 1611 individuals for more than 3 days per week. Conversely, the Non-changed SES group had 573 participants for 1 day or less per week, 776 participants for 3 days or less per week, and 1723 participants for more than 3 days per week in VPA. For muscular strength activities, the Lower SES group had 597 individuals participating for 1 day or less per week, 609 individuals for 3 days or less per week, and 1866 individuals for more than 3 days per week. The Non-changed SES group, on the other hand, had 499 participants for 1 day or less per week, 568 participants for 3 days or less per week, and 2005 participants for more than 3 days per week in muscular strength activities.

Overall, there were no significant differences in the number of participants engaging in total PA, VPA, and muscular strength activities between the two groups (p > 0.05). However, the Lower SES group exhibited a lower prevalence of VPA and muscular strength activities (i.e., ≤ 1 day and ≤ 3 days) compared to the Non-changed SES group. Notably, the total time spent in SB (minutes per week) showed a significant difference between the two groups only for Low SB (p = 0.00; 95% CI = -64.87–-21.44). The Lower SES group spent 582.69 ± 256.94 minutes per week in Low SB, while the Non-changed SES group spent 625.85 ± 237.48 minutes per week. For High SB, the Lower SES group spent 1710.05 ± 284.63 minutes per week, and for Medium SB, they spent 1141.10 ± 124.91 minutes per week. In comparison, the Non-changed SES group spent 1712.69 ± 284.46 minutes per week for High SB and 1131.85 ± 125.49 minutes per week for Medium SB.

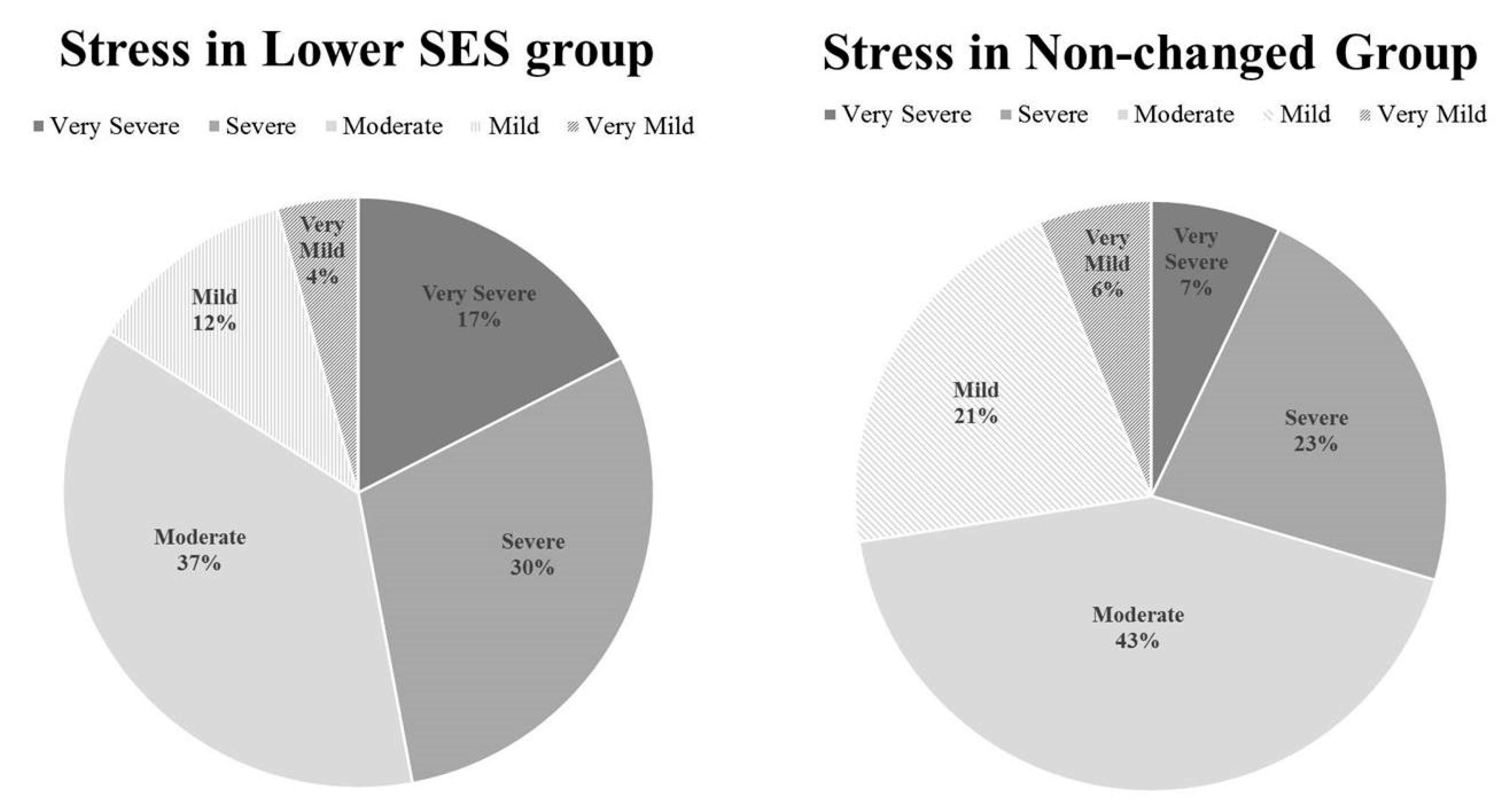

Figure 2 illustrates a graphical depiction of the daily stress levels comparison between the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group. In the Lower SES group, the highest proportion of participants reported experiencing a moderate level of stress, accounting for 37% of the sample. This was followed by 30% of participants reporting a severe level of stress and 17% reporting a very severe level of stress. In contrast, in the Non-changed SES group, the majority of participants (43%) reported experiencing a moderate level of stress. Subsequently, 23% of participants reported a severe level of stress, and 21 reported a mild level of stress.

4. Discussion

Adequate PA plays a crucial role in promoting the healthy development of youth, encompassing various physical, mental, and social health benefits (Janssen & LeBlanc, 2010; Poitras et al., 2016). However, the outbreak of COVID-19 and subsequent restrictions have significantly limited opportunities for youth to engage in PA and exercise (Schmidt et al., 2020). These restrictions have also led to economic crises and recessions, impacting the family SES (Dang & Nguyen, 2021). Previous studies have highlighted the significant association between a family SES and health-related behaviors among young individuals (Bauman et al., 2012; Bauman et al., 2002; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2000). Considering the crucial interplay between external factors, family processes, and children’s perceptions (Conger et al., 2010; Goodenow, 1993), it becomes essential to investigate the impact of children’s perception of changes in family SES during COVID-19, regardless of actual SES, as it may serve as an essential determinant of youth’s health-related behavior. However, there remains a dearth of research examining the associations of PA, SB, mental health, and perception of family SES among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, this study aimed to examine the associations between PA, SB, and perceived stress among Korean adolescents, specifically focusing on the changes in the perception of family SES in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020.

The current study compared the association of PA, SB, and stress levels among adolescents in the Lower SES group and the Non-changed SES group based on changes in family SES perception. Our findings revealed that adolescents in the Lower SES group were less likely to participate in VPA and muscular strength activities compared to the Non-changed SES group (p < 0.001). Specifically, adolescents in the Lower SES group had 1.40 times higher odds of participating in VPA for less than 1 day (p = 0.001, OR = 1.15), 1.30 times higher odds of participating in VPA for less than 3 days (p < 0.001, OR = 1.30), 1.38 times higher odds of participating in muscular strength activities for less than 1 day (p < 0.001, OR = 1.38), and 1.31 times higher odds of participating in muscular strength activities for less than 3 days (p = 0.001, OR = 1.31) compared to the Non-changed SES group. However, there were no significant differences in total PA between the two groups (p > 0.05).

It is widely acknowledged that SES is closely linked to health outcomes (House, 2002), and numerous studies have explored the association between SES and health-related behaviors, particularly in relation to PA or SB (Grzywacz & Marks, 2001; R. E. Lee & Cubbin, 2002). In our study, we observed that the Lower SES group had a larger population of individuals in the low to middle classes of actual family SES (73.9%), while the Non-changed SES group had a higher representation in the middle to high classes (95.9%). Based on this observation, we propose that adolescents from low SES families were more likely to perceive changes in their family SES compared to those from high SES families during the COVID-19 pandemic. This perception of the economic downturn may have influenced reduced participation in VPA and muscular strength activities among adolescents in the lower SES group.

Although we accounted for actual family SES as a covariate for adjustment using categorical variables (i.e., high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, and low). It is essential for future research to incorporate more precise measures of parents’ actual income levels. Additionally, our findings align with previous observations that adolescents with higher SES backgrounds tend to engage in more PA compared to their counterparts from lower SES backgrounds (Stalsberg & Pedersen, 2010). The lower levels of PA observed in adolescents from low SES families can be attributed to economic factors, including unfavorable neighborhood environments characterized by a lack of recreational areas and longer distances to access PA facilities (Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page, & Popkin, 2006). Given that the Lower SES group in our study primarily consisted of adolescents from the lower classes of SES and they perceived a decline in their family SES following the COVID-19 outbreak, it is reasonable to inform that these adolescents may have limited opportunities to participate in VPA and muscular strength activities, which often require parental financial support and access to sports facilities or academies.

Reciprocally, SB exhibited divergent outcomes when compared to PA, with significant discrepancies noted between the two cohorts. Our study focused on the examination of adolescents belonging to the Lower SES group, evaluating their weekly sitting duration (in minutes) relative to the Non-changed SES group. The data indicated a marked reduction of 40% in high SB (p < 0.001, OR = 0.67) and 25% in medium SB (p < 0.001, OR = 0.79) within the Lower SES group, in contrast to their peers in the Non-changed SES group. These findings presented a departure from prior research, which had previously established an inverse correlation between SB and SES in adolescents (Mielke, Brown, Nunes, Silva, & Hallal, 2017). One plausible interpretation for these observed SB patterns in our study is linked to the prevailing emphasis on academic excellence in South Korea, where education attainment holds substantial significance within the SES construct (Robinson, 1994; Son, 2004). Adolescents from high-SES households may exhibit an increased allocation of SB hours compared to their low-SES counterparts due to heightened involvement in private tutoring or after-school academies (J. Kim, 2013; J.-S. Kim & Bang, 2017; Park, 2009). In light of this empirical evidence and considering the perceived decline in family SES and lower level of academic performance among the Lower SES group in our study, it is conceivable that their perception of family SES might indirectly correlate with educational engagement and reduced SB. To ensure a comprehensive comprehension of the association observed, it is imperative to note that our analysis incorporated academic performance as a covariate, serving as a reflection of their educational involvement. Nonetheless, future investigations should account for other pertinent factors related to SB.

Furthermore, within our study, adolescents from the Lower SES group manifested a 2.27-fold higher likelihood of encountering very severe levels of stress level (p < 0.001, OR = 2.27) and a 1.23-fold higher likelihood of experiencing severe stress levels, though the latter did not attain statistical significance. These escalated stress levels among adolescents can be attributed to a multitude of factors, encompassing economic deterioration resulting in heightened financial burdens, adverse shifts in parental mental health, disruptions in marital interaction, and potential declines in parenting quality (Solantaus, Leinonen, & Punamäki, 2004). The imposition of economic constraints during the COVID-19 pandemic likely accentuated these stressors, disproportionately affecting the Lower SES group in our study, who perceived a decline in their family SES.

Adolescents, due to their sensitive and critical developmental stage, are particularly susceptible to the deleterious effects of chronic stress (Kong, So, & Jang, 2021). Notably, Kong et al. reported that stress could profoundly impact both the physical and mental health of individuals, contributing to conditions such as depression, suicide, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular disease, and compromised immune function (Kong et al., 2021). Concurrently, extant research has demonstrated the beneficial role of PA and exercise in promoting mental health (Khalsa, Hickey-Schultz, Cohen, Steiner, & Cope, 2012; O’Dougherty, Hearst, Syed, Kurzer, & Schmitz, 2012; Scott et al., 2012). Significantly, Kong et al. elucidated a noteworthy association between engaging in more than 20 minutes of VPA at least three times per week and experiencing lower stress levels among adolescents (Kong et al., 2021). Similarly, Adams et al. emphasized the relationship between engaging in muscular strength activity and improved mental health (Adams, Moore, & Dye, 2007). Therefore, based on the existing evidence, augmenting involvement in VPA and muscular strength activities may serve as a potential strategy to ameliorate daily stress levels and enhance mental health, particularly among adolescents in the Lower SES group in our study. Nonetheless, it is essential to acknowledge that the findings generated inconsistent results, with the Lower SES group exhibiting a lower likelihood of experiencing mild-stress levels compared to the Non-changed SES group. Consequently, further investigations are necessary to explore additional pertinent factors that could influence stress levels among adolescents.

5. Strength and Limitations

The present study demonstrates several noteworthy strengths. Firstly, it represents the inaugural investigation to explore the association between PA, SB, and stress, particularly among age-matched adolescents, by categorizing the cohorts based on their perception of changes in family SES during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, our research yields novel findings by analyzing significant disparities in PA, SB, and stress among adolescents, taking into account their perception of family SES during the COVID-19 period. Nonetheless, the study is not without its limitations, which necessitate acknowledgment. First, the data on PA and SB were derived from self-reported responses, potentially leading to either underestimation or overestimation by individuals (Cerin et al., 2016). Moreover, the PA data were collected based on participation dates rather than precise time measurements, making direct comparison with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) PA guidelines challenging. Additionally, the study did not incorporate the actual income level of parents due to the lack of accurate specifications for categorizing their income levels in the survey. Instead, we utilized an actual family SES variable as a covariate, which was categorized into the five hierarchical classes based on the survey data. To improve the validity of study results, future research should utilize reliable data on the actual family income levels as an SES measure.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the study has identified notable variations in levels of PA, SB, and stress levels among Korean adolescents, contingent on their perception of family SES in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. These findings offer valuable insights into the potential significance of promoting VPA and muscular strength activities among adolescents to bolster their physical and mental well-being during future pandemics. Based on the findings, we propose the implementation of targeted policies aimed at adolescents from low SES families or those susceptible to experiencing a decline in family SES following the future disease pandemic. Moreover, to enhance comprehension, it is crucial to gather further evidence from diverse countries worldwide to investigate the association between PA, SB, mental health, SES, and perception of SES among adolescents during disease pandemics.

Author Contributions

Data curation, J.S.K., and J.-M.L.; formal analysis, J.-M.L.; investigation, J.S.K.; methodology, J.-H.P.; project administration, J.-M.L.; writing—original draft, J.S.K.; writing review and editing, J.-H.P., I.-W.H., Y.-D.K., and J.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from Kyung Hee University in 2022 (KHU-20220924).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

All authors like to thank all adolescents who participated in the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Adams, T.B.; Moore, M.T.; Dye, J. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Mental Health in a National Sample of College Females. Women Heal. 2007, 45, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.; Joung, H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kwon, K.N.; Kim, Y.T.; Park, S.-W. Test-Retest Reliability of a Questionnaire for the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. J. Prev. Med. Public Heal. 2010, 43, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, E.J.; El-Sheikh, M. Familial Risk Moderates the Association Between Sleep and zBMI in Children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.C.; Zieff, G.; Stanford, K.; Moore, J.B.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Hanson, E.D.; Barone Gibbs, B.; Kline, C.E.; Stoner, L. COVID-19 Impact on Behaviors across the 24-Hour Day in Children and Adolescents: Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep. Children 2020, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, A. E. , Reis, R. S., Sallis, J. F., Wells, J. C., Loos, R. J., Martin, B. W., & Group, L. P. A. S. W. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? The lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar]

- E Bauman, A.; Sallis, J.F.; A Dzewaltowski, D.; Owen, N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: The role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.P.; Gregory, A.M. Editorial Perspective: Perils and promise for child and adolescent sleep and associated psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2020, 61, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzek, T. , Poulain, T., Vogel, M., Engel, C., Bussler, S., Körner, A.,... Kiess, W. Relations between sleep duration with overweight and academic stress—just a matter of the socioeconomic status? Sleep health 2019, 5, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Cain, K.L.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Owen, N.; Conway, T.L.; Cochrane, T.; VAN Dyck, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Mitáš, J.; Toftager, M.; et al. Correlates of Agreement between Accelerometry and Self-reported Physical Activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.B.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: summary of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R. D. , Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of marriage and family 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.-A.H.; Nguyen, C.V. Gender inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic: Income, expenditure, savings, and job loss. World Dev. 2020, 140, 105296–105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, W. D. , Ashcroft, E. C., Lorenz-Dant, K., & Comas-Herrera, A. (2020). Mitigating the Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Review of International Measures to Support Community-Based Care Services: A Review of Initial International Policy Reponses. Report in LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE, 19 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow, C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools 1993, 30, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; McMurray, R.G.; Popkin, B.M. Determinants of Adolescent Physical Activity and Inactivity Patterns. Pediatrics 2000, 105, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Page, P.; Popkin, B.M. Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity. PEDIATRICS 2006, 117, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Social Inequalities and Exercise during Adulthood: Toward an Ecological Perspective. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 202–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.D.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Rhodes, R.E.; Faulkner, G.; Moore, S.A.; Tremblay, M.S. Canadian children's and youth's adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic: A decision tree analysis. J. Sport Heal. Sci. 2020, 9, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Davis, M.M.; Chervin, R.D. No Independent Association between Insufficient Sleep and Childhood Obesity in the National Survey of Children's Health. Sleep Med. 2011, 7, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2008). Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008, A1-H14.

- House, J.S. Understanding Social Factors and Inequalities in Health: 20th Century Progress and 21st Century Prospects. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.B.S.; Hickey-Schultz, L.; Cohen, D.; Steiner, N.; Cope, S. Evaluation of the Mental Health Benefits of Yoga in a Secondary School: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Behav. Heal. Serv. Res. 2011, 39, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-A. Social Distancing and Public Health Guidelines at Workplaces in Korea: Responses to Coronavirus Disease-19. Saf. Heal. Work. 2020, 11, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-J.; Lee, H.-J. Relationship between the Toothbrushing Behavior and Hand Hygiene Practices of Korean Adolescents: A Study Focused on the 15th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey Conducted in 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on long-term care in South Korea and measures to address it. Report in LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE, 7 May 2020.

- Kim, J. (2013). Stratification phenomenon of educational aspirations-with a focus on ‘cooling-down pattern’of educational aspirations among the working-class. Asia-Pacific Collaborative Education Journal, 9(1), 27-39.

- Kim, J.-S.; Bang, H. Education fever: Korean parents’ aspirations for their children’s schooling and future career. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2016, 25, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; So, W.-Y.; Jang, S. The Association between Vigorous Physical Activity and Stress in Adolescents with Asthma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.E.; Cubbin, C. Neighborhood Context and Youth Cardiovascular Health Behaviors. Am. J. Public Heal. 2002, 92, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritis, I.; Houdart, S.; El Ouadrhiri, Y.; Bigard, X.; Vuillemin, A.; Duché, P. How to deal with COVID-19 epidemic-related lockdown physical inactivity and sedentary increase in youth? Adaptation of Anses’ benchmarks. Arch. Public Heal. 2020, 78, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; Brown, W.J.; Nunes, B.P.; Silva, I.C.M.; Hallal, P.C. Socioeconomic Correlates of Sedentary Behavior in Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 47, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Dougherty, M.; Hearst, M.O.; Syed, M.; Kurzer, M.S.; Schmitz, K.H. Life events, perceived stress and depressive symptoms in a physical activity intervention with young adult women. Ment. Heal. Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-K. ‘English fever’in South Korea: Its history and symptoms. English Today 2009, 25, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.-K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Lim, C. Promoting Parent and Child Physical Activity Together: Elicitation of Potential Intervention Targets and Preferences. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2017, 45, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Berry, T.; Faulkner, G.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; O’reilly, N.; Tremblay, M.S.; Vanderloo, L. Parental support of the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: prevalence and correlates. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Social Status and Academic Success in South Korea. Comp. Educ. Rev. 1994, 38, 506–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.C.E.; Anedda, B.; Burchartz, A.; Eichsteller, A.; Kolb, S.; Nigg, C.; Niessner, C.; Oriwol, D.; Worth, A.; Woll, A. Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: A natural experiment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.M.; Hermens, D.F.; Glozier, N.; Naismith, S.L.; Guastella, A.J.; Hickie, I.B. Targeted primary care-based mental health services for young Australians. The Medical Journal of Australia 2012, 196, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solantaus, T. , Leinonen, J., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2004). Children’s mental health in times of economic recession: replication and extension of the family economic stress model in Finland. Developmental psychology, 40(3), 412-429.

- Son, M. (2004). Commentary: why the educational effect is so strong in differentials of mortality in Korea? International journal of epidemiology, 33(2), 308-310.

- Stalsberg, R.; Pedersen, A.V. Effects of socioeconomic status on the physical activity in adolescents: a systematic review of the evidence. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Fallani, S.; Voller, F.; Silvestri, C. Treatment for COVID-19: An overview. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 889, 173644–173644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, C.; Fallani, S.; Voller, F.; Silvestri, C. Treatment for COVID-19: An overview. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 889, 173644–173644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderloo, L.M.; Carsley, S.; Aglipay, M.; Cost, K.T.; Maguire, J.; Birken, C.S. Applying Harm Reduction Principles to Address Screen Time in Young Children Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, L.; Vanderloo, L.; Berry, T.R.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; O’reilly, N.; Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Tremblay, M.S.; Faulkner, G. Assessing the social climate of physical (in)activity in Canada. BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenic, N.; Taiar, R.; Gilic, B.; Blazevic, M.; Maric, D.; Pojskic, H.; Sekulic, D. Levels and Changes of Physical Activity in Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Contextualizing Urban vs. Rural Living Environment. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).