Submitted:

07 September 2023

Posted:

08 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

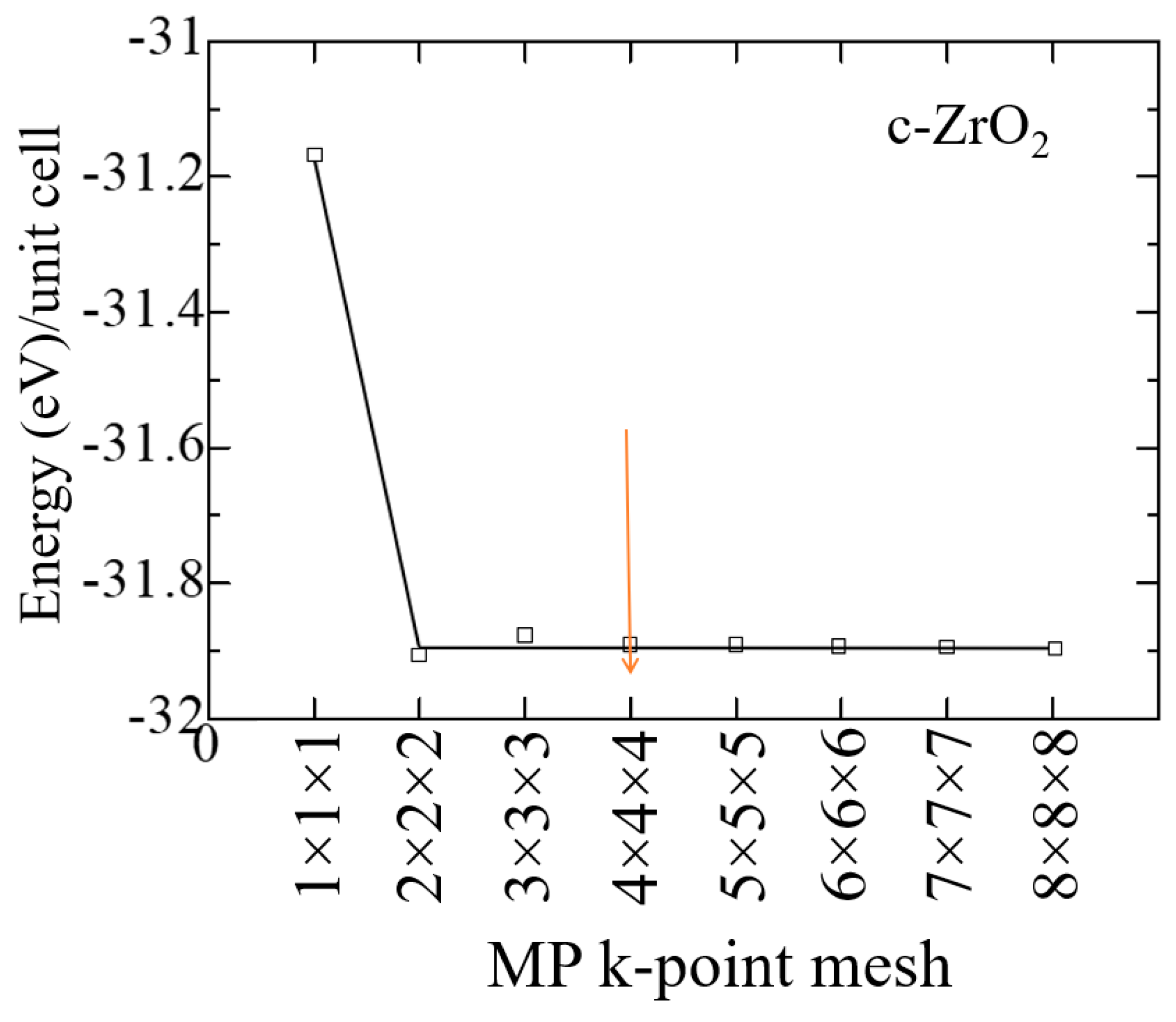

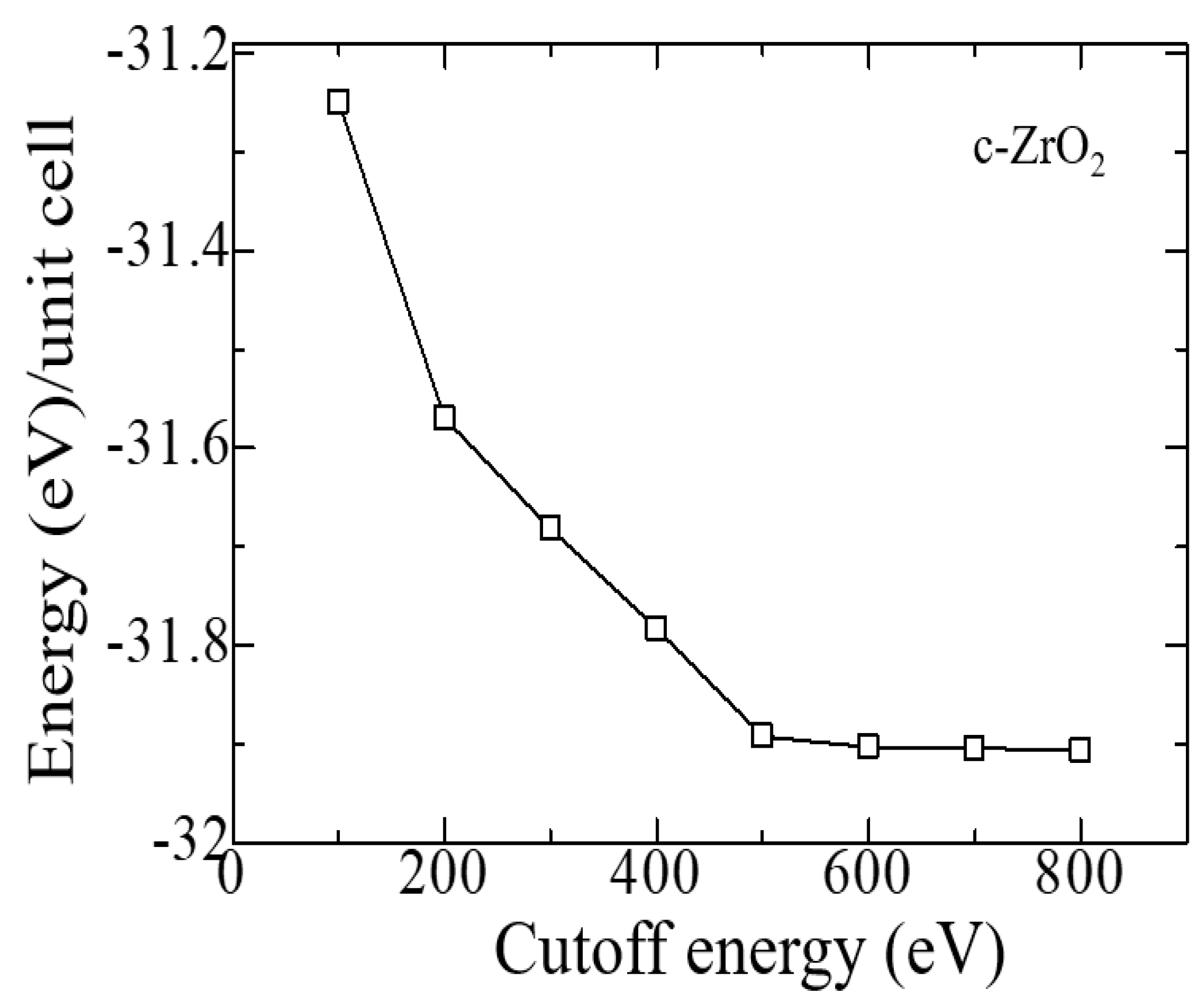

2. Ab-initio simulation details

3. Results and discussion

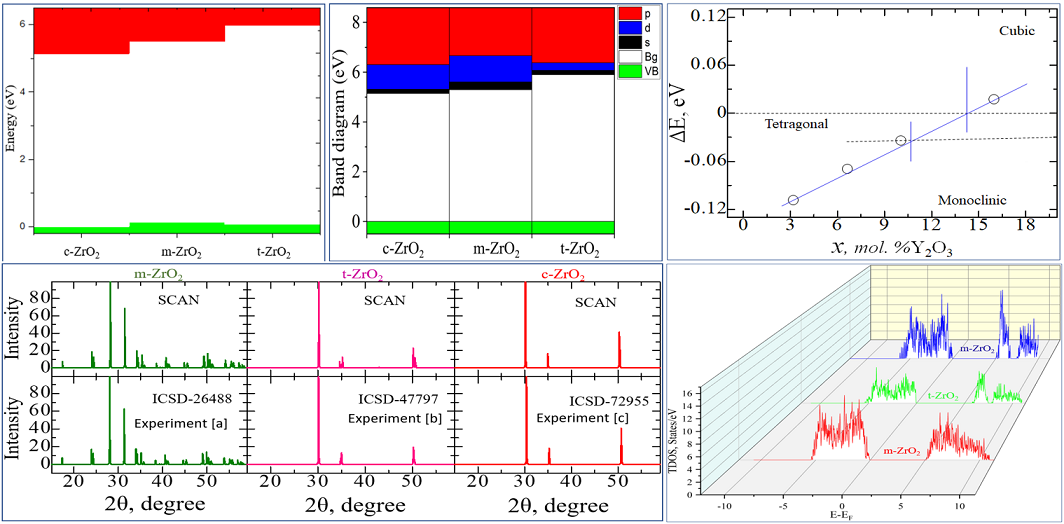

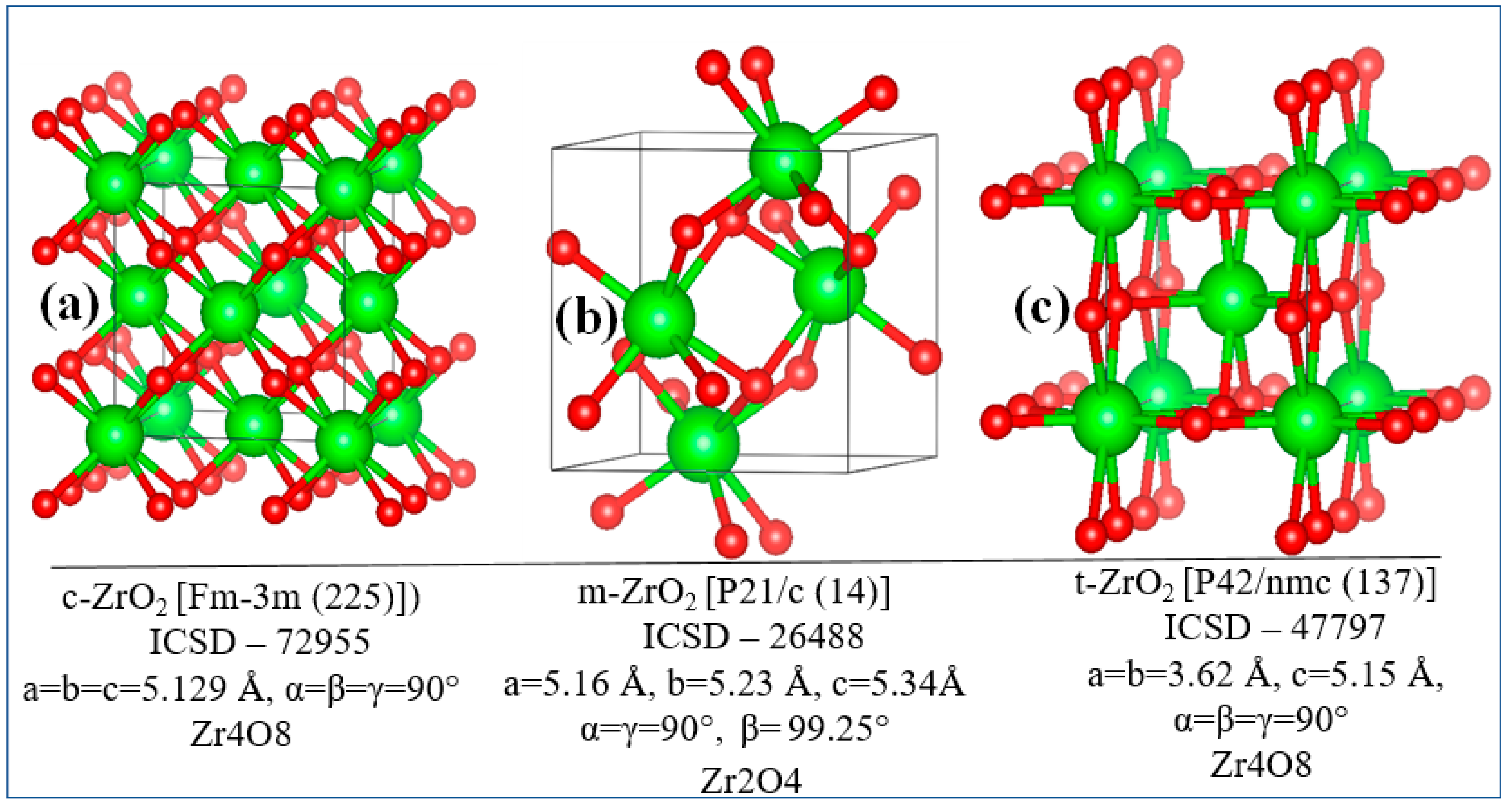

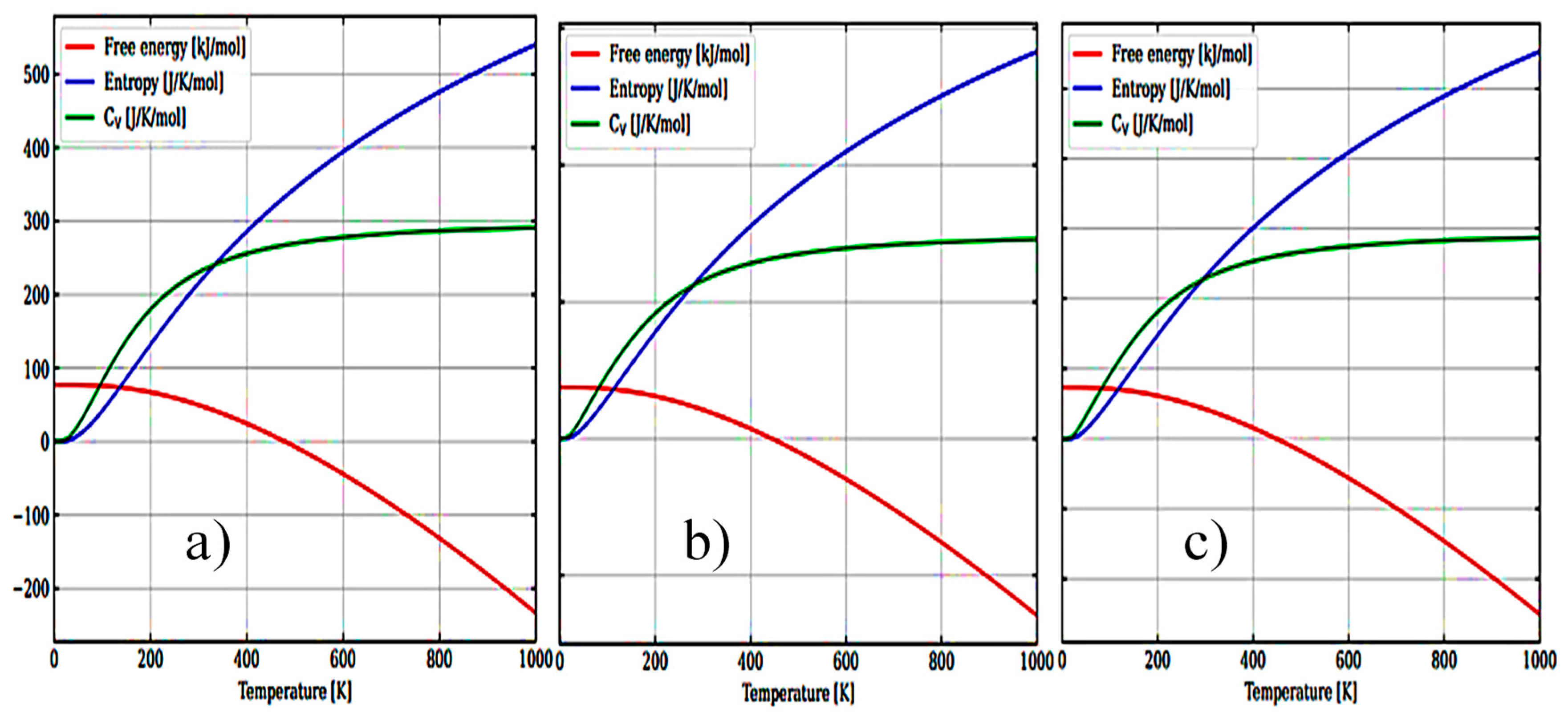

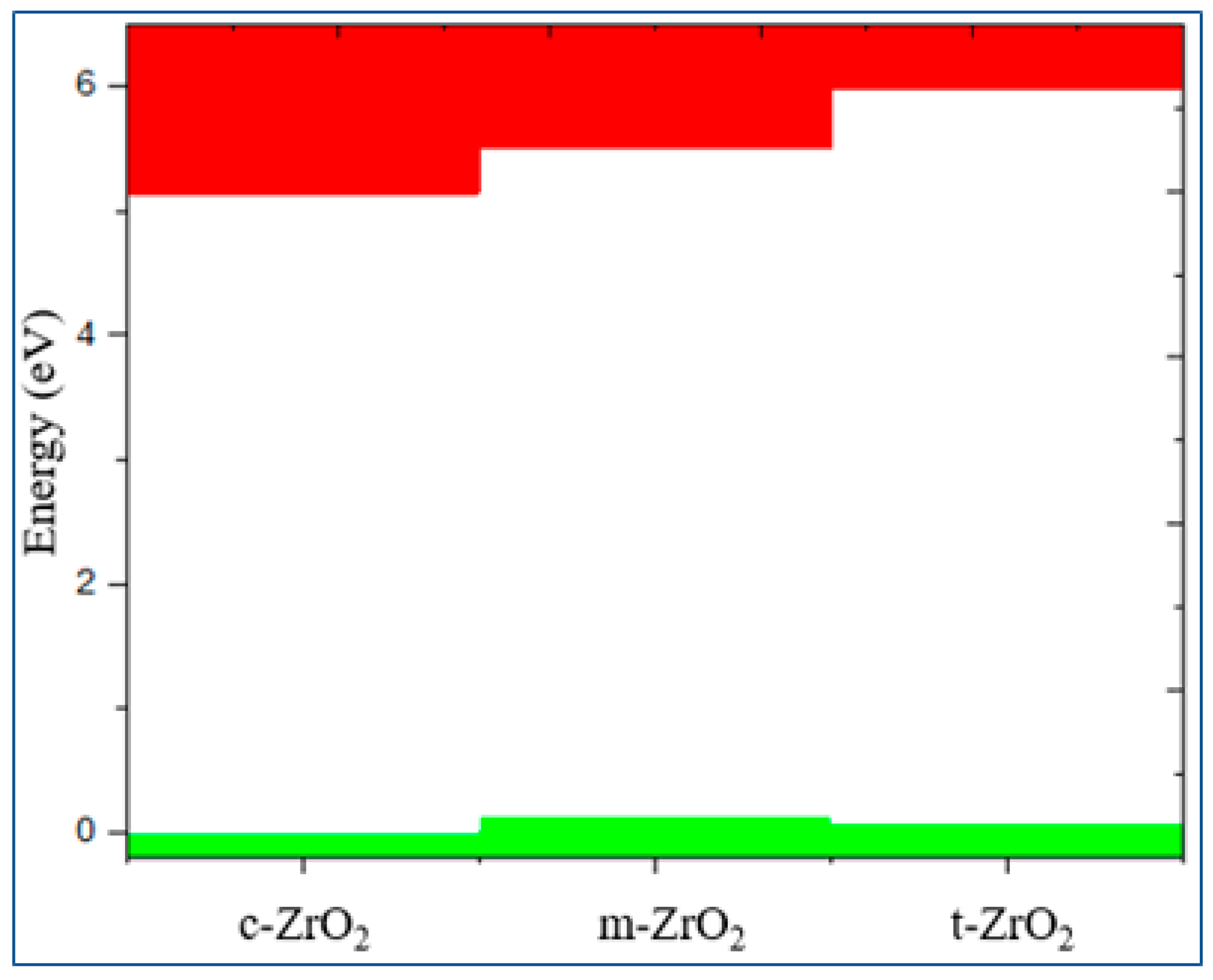

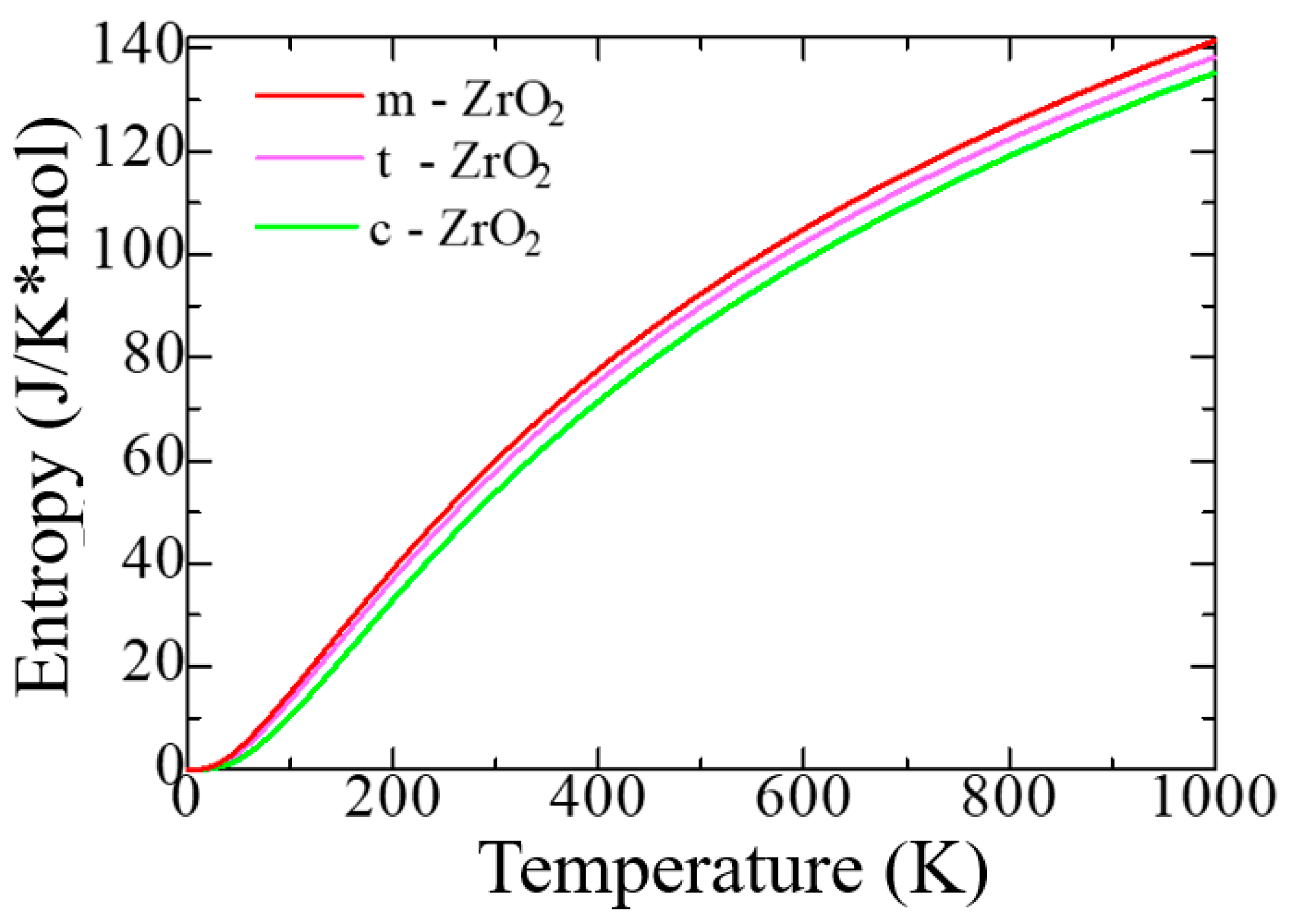

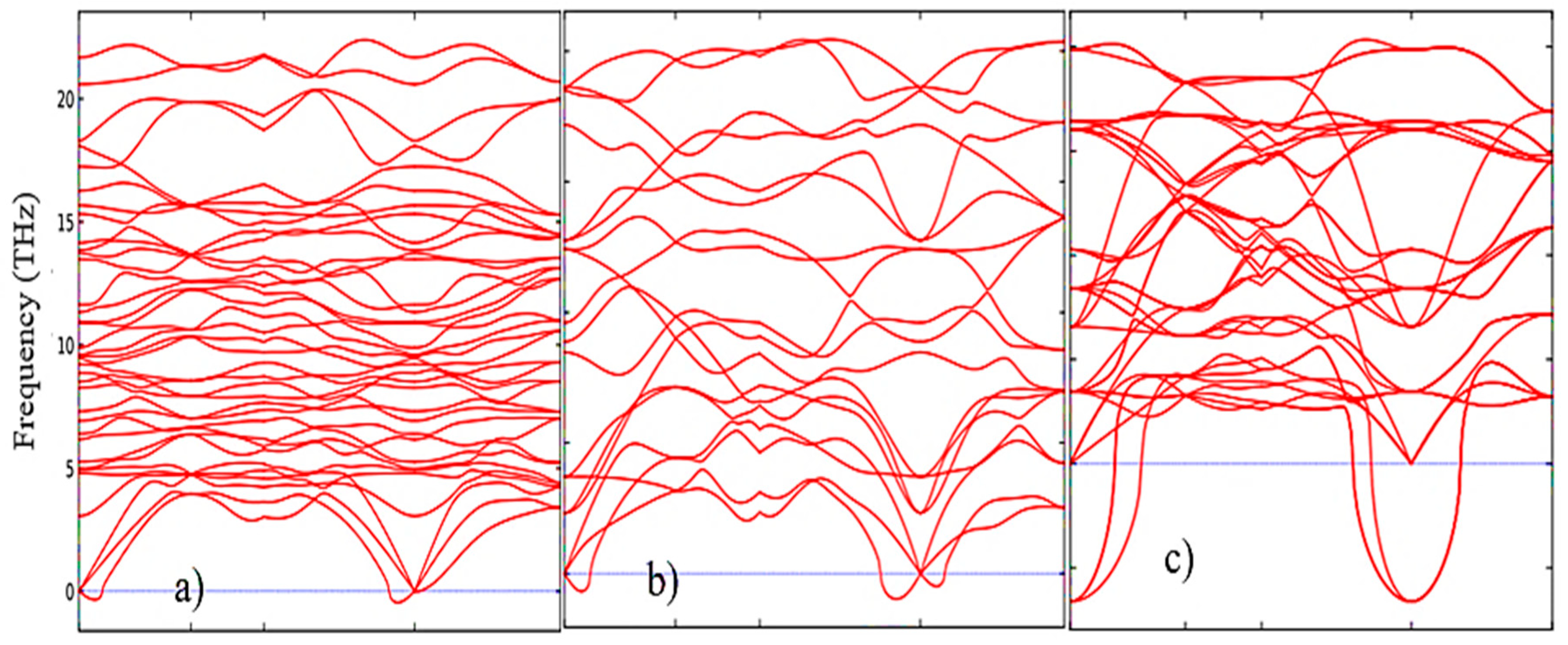

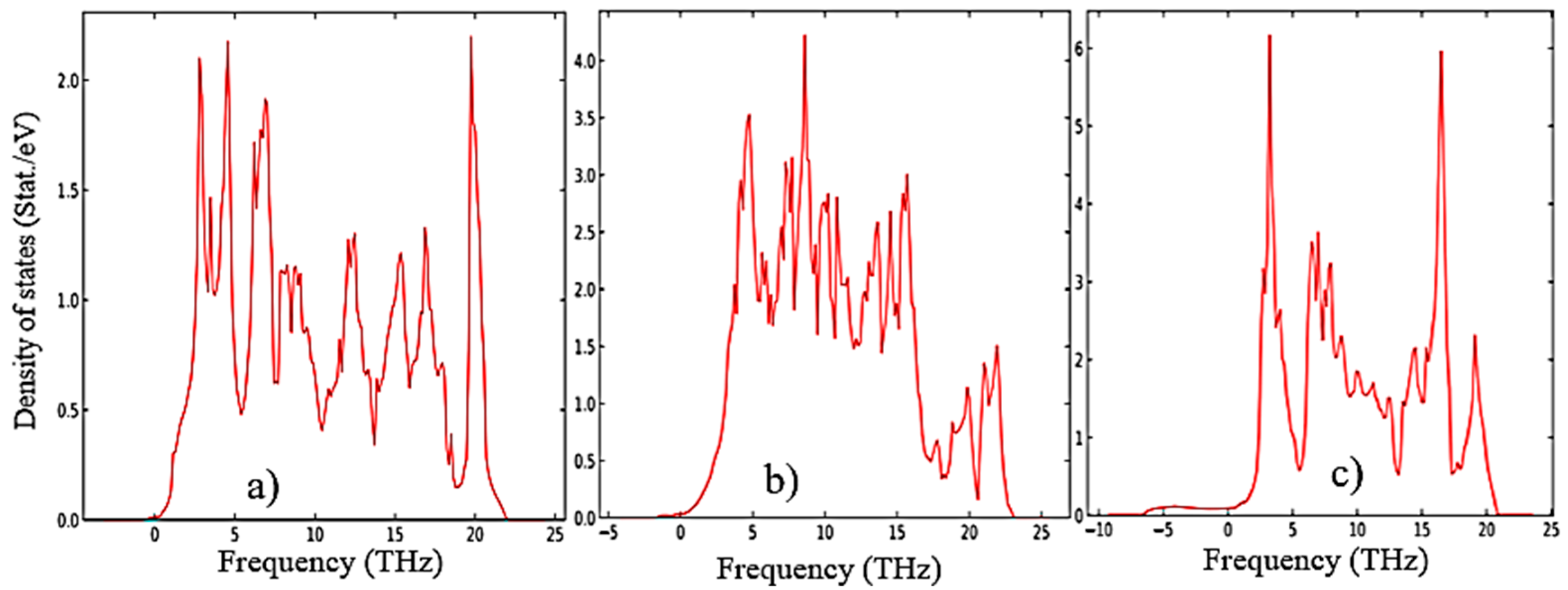

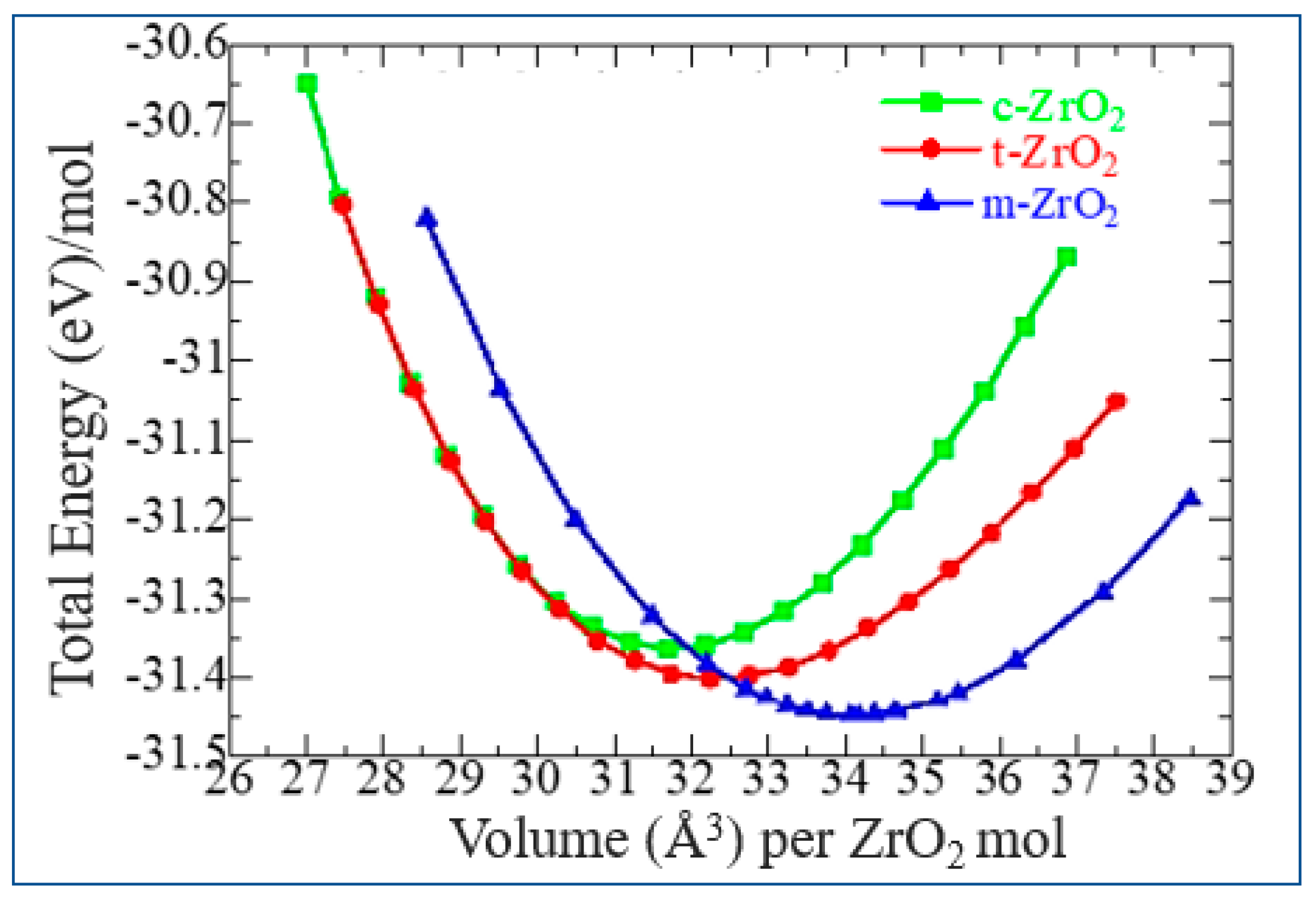

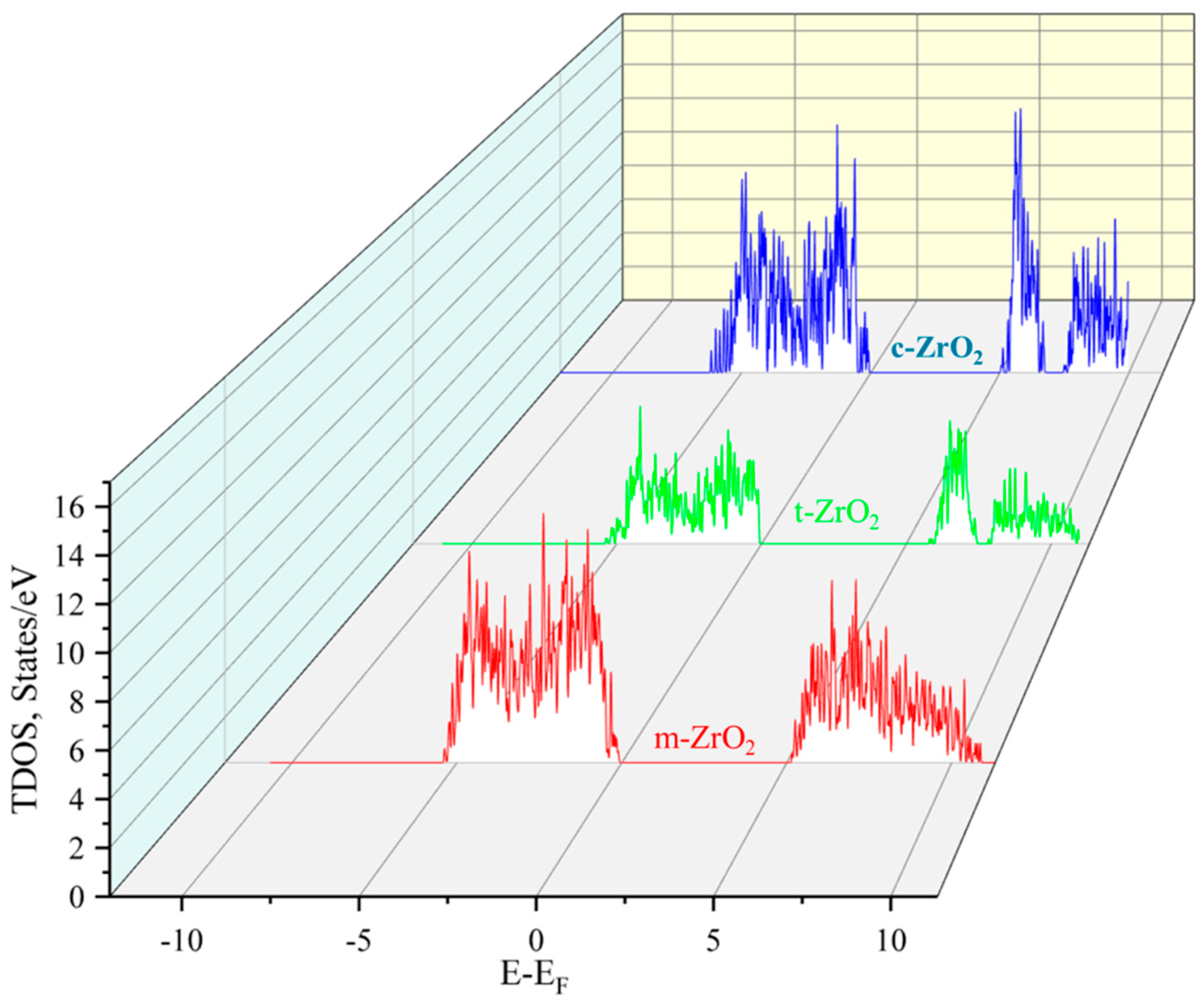

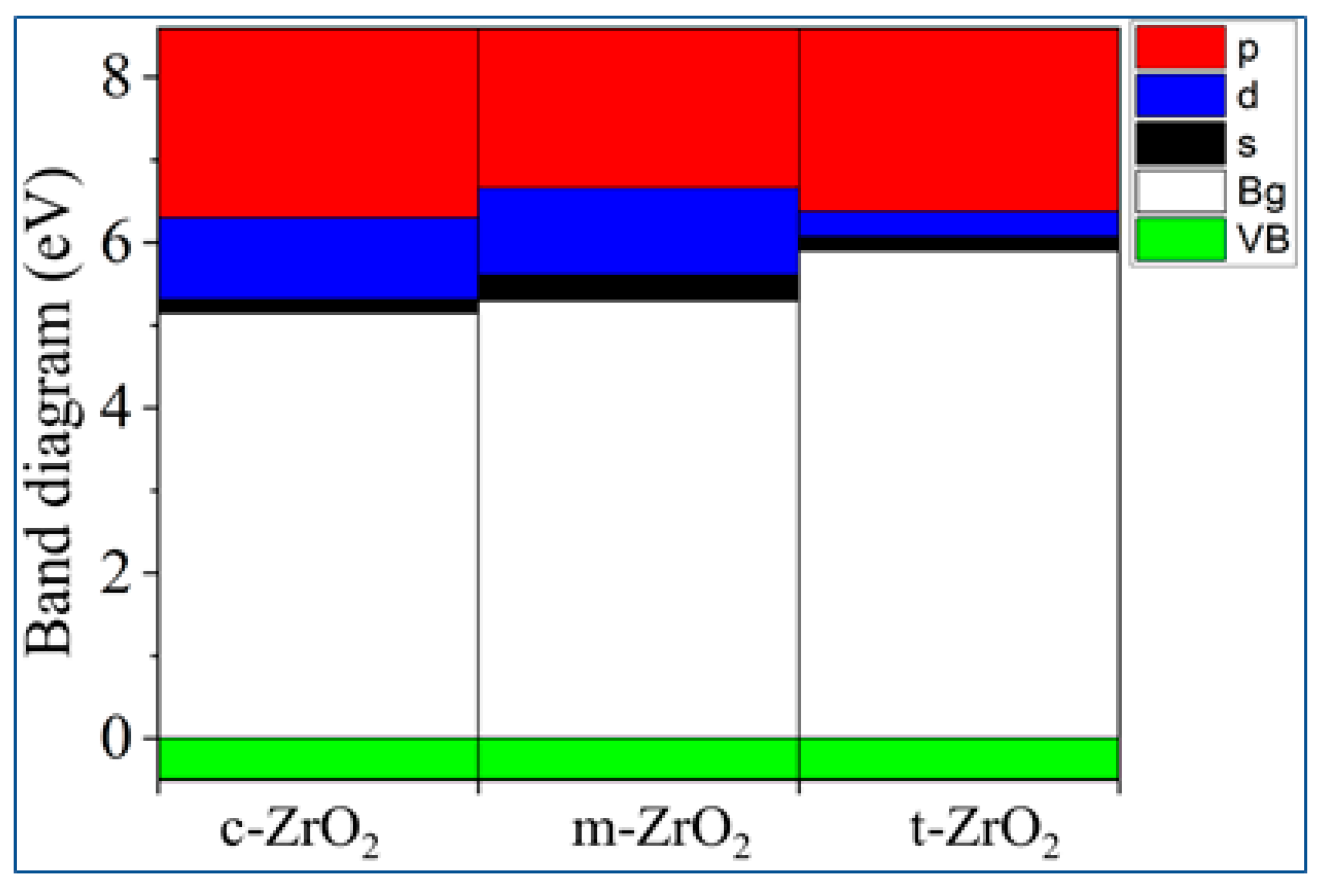

3.1. Structural, electronic and phonon properties of ZrO2

3.2. Stabilization of m-ZrO2 and electronic properties of YSZ

4. Conclusion

Funding

References

- Chu, S., Cui, Y., & Liu, N. (2016). The path towards sustainable energy. Nature Materials, 16(1), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S., & Majumdar, A. (2012). Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature, 488(7411), 294–303. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D., Xiao, M., Zou, G., Liu, L., Duley, W. W., & Zhou, Y. N. (2018). Self-Powered Wearable Electronics Based on Moisture Enabled Electricity Generation. Advanced Materials, 30(18), 1705925. [CrossRef]

- Shao, C., Ji, B., Xu, T., Gao, J., Gao, X., Xiao, Y., Zhao, Y., Chen, N., Jiang, L., & Qu, L. (2019). Large-Scale Production of Flexible, High-Voltage Hydroelectric Films Based on Solid Oxides. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 11(34), 30927–30935. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Ohtake, K., Arashi, H., Kakihana, M., & Yoshimura, M. (1993). Determination of cubic-tetragonal phase boundary in Zr1− XYX O2− X/2 solid solutions by Raman spectroscopy. Journal of applied physics, 74(12), 7603-7605.

- Yashima, M., Sasaki, S., Kakihana, M., Yamaguchi, Y. A. S. U. O., Arashi, H. A. R. U. O., & Yoshimura, M. A. S. A. H. I. R. O. (1994). Oxygen-induced structural change of the tetragonal phase around the tetragonal–cubic phase boundary in ZrO2–YO1. 5 solid solutions. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, 50(6), 663-672. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Kakihana, M., & Yoshimura, M. (1996). Metastable-stable phase diagrams in the zirconia-containing systems utilized in solid-oxide fuel cell application. Solid State Ionics, 86, 1131-1149. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Ohtake, K., Kakihana, M., Arashi, H., & Yoshimura, M. (1996). Determination of tetragonal-cubic phase boundary of Zr1− XRXO2− X2 (R= Nd, Sm, Y, Er and Yb) by Raman scattering. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 57(1), 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Ishizawa, N., & Yoshimura, M. (1993). High-Temperature X-ray Study of the Cubic-Tetragonal Diffusionless Phase Transition in the ZrO2─ ErO1. 5 System: I, Phase Change between Two Forms of a Tetragonal Phase, t′-ZrO2 and t ″-ZrO2, in the Compositionally Homogeneous 14 mol% ErO1. 5-ZrO2. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 76(3), 641-648. [CrossRef]

- Leger, J. M., Tomaszewski, P. E., Atouf, A., & Pereira, A. S. (1993). Pressure-induced structural phase transitions in zirconia under high pressure. Physical Review B, 47(21), 14075. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. G. (1980). New high pressure phases of ZrO2 and HfO2. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 41(4), 331-334. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Mitsuhashi, T., Takashina, H., Kakihana, M., Ikegami, T., & Yoshimura, M. (1995). Tetragonal—monoclinic phase transition enthalpy and temperature of ZrO2-CeO2 solid solutions. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 78(8), 2225-2228. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Jin, Z., & Huang, P. (1991). Thermodynamic Assessment of the ZrO2─ YO1. 5 System. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 74(7), 1569-1577. [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M., Hirose, T., Katano, S., Suzuki, Y., Kakihana, M., & Yoshimura, M. (1995). Structural changes of ZrO 2-CeO 2 solid solutions around the monoclinic-tetragonal phase boundary. Physical Review B, 51(13), 8018. [CrossRef]

- Clearfield, A. (1964). Crystalline hydrous zirconia. Inorganic Chemistry, 3(1), 146-148. [CrossRef]

- Doroshkevich, A. S., Nabiev, A. A., Pawlukojć, A., Doroshkevich, N. V., Rahmonov, K. R., Khamzin, E. K., ... & Ibrahim, M. A. (2019). Frequency modulation of the Raman spectrum at the interface DNA-ZrO 2 nanoparticles. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry, 62(2), 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Kvist, in: Physics of Electrolytes, Vol. 1, ed. J. Hladik (Academic Press, London, 1972) p. 319.

- Lughi, V., & Sergo, V. (2010). Low temperature degradation-aging-of zirconia: A critical review of the relevant aspects in dentistry. Dental materials, 26(8), 807-820. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K., Kuwajima, H., & Masaki, T. (1981). Phase change and mechanical properties of ZrO2-Y2O3 solid electrolyte after ageing. Solid State Ionics, 3, 489-493. [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P., & Kohn, W. (1964). Inhomogeneous electron gas. Physical review, 136(3B), B864. [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J. P., Burke, K., & Ernzerhof, M. (1996). Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters, 77(18), 3865. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A., & Perdew, J. P. (2015). Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Physical review letters, 115(3), 036402. [CrossRef]

- Kresse G, Furthmuller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996; 6:15–50. [CrossRef]

- Howard, C. J., Hill, R. J., & Reichert, B. E. (1988). Structures of ZrO2 polymorphs at room temperature by high-resolution neutron powder diffraction. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, 44(2), 116-120. [CrossRef]

- Teufer, G. (1962). The crystal structure of tetragonal ZrO2. Acta Crystallographica, 15(11), 1187-1187. [CrossRef]

- Martin, U., Boysen, H., & Frey, F. (1993). Neutron powder investigation of tetragonal and cubic stabilized zirconia, TZP and CSZ, at temperatures up to 1400 K. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, 49(3), 403-413. [CrossRef]

- Martin, U., Boysen, H., & Frey, F. (1993). Neutron powder investigation of tetragonal and cubic stabilized zirconia, TZP and CSZ, at temperatures up to 1400 K. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science, 49(3), 403-413. [CrossRef]

- Pascal, R., & Pross, A. (2015). Stability and its manifestation in the chemical and biological worlds. Chemical Communications, 51(90), 16160-16165. [CrossRef]

- Teter, D. M., Gibbs, G. V., Boisen Jr, M. B., Allan, D. C., & Teter, M. P. (1995). First-principles study of several hypothetical silica framework structures. Physical Review B, 52(11), 8064.

- Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E., & Ernzerhof, M. (2003). Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. The Journal of chemical physics, 118(18), 8207-8215. [CrossRef]

- Verma P, Truhlar D. HLE16: A Local Kohn-Sham Gradient Approximation with Good Performance for Semiconductor Band Gaps and Molecular Excitation Energies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:380–87. [CrossRef]

- Asgerov, E.B.; Beskrovnyy, A.I.; Doroshkevich, N.V.; Mita, C.; Mardare, D.M.; Chicea, D.; Lazar, M.D.; Tatarinova, A.A.; Lyubchyk, S.I.; Lyubchyk, S.B.; Lyubchyk, A.I.; Doroshkevich, A.S. Reversible Martensitic Phase Transition in Yttrium-Stabilized ZrO2 Nanopowders by Adsorption of Water, Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3, 435. [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D. D., Kholmurodov, K. T., Husenzoda, M. A, Lyubchyk, A., & Burhonzoda, A. S. (2022). Molecular Adsorption of H2O on TiO2 and TiO2: Y Surfaces. Journal of Human, Earth, and Future, 3(2), 213-222. [CrossRef]

- Nematov D. Influence of Iodine Doping on the Structural and Electronic Properties of CsSnBr3. International Journal of Applied Physics 2022; 7:36-47.

- Nematov D, Kholmurodov K, Yuldasheva D, Rakhmonov K, Khojakhonov I. Ab-initio Study of Structural and Electronic Properties of Perovskite Nanocrystals of the CsSn[Br1−xIx]3 Family. HighTech and Innovation Journal 2022; 3:140-50. [CrossRef]

- Davlatshoevich D.N. Investigation Optical Properties of the Orthorhombic System CsSnBr3-xIx: Application for Solar Cells and Optoelectronic Devices. Journal of Human, Earth, and Future, 2021; 2, 404-411. [CrossRef]

- Davlatshoevich N. D, Ashur K, Saidali B.A, Kholmirzo Kh, Lyubchyk A, Ibrahim M. Investigation of structural and optoelectronic properties of N-doped hexagonal phases of TiO2 (TiO2-xNx) nanoparticles with DFT realization: Optimization of the band gap and optical properties for visible-light absorption and photovoltaic applications. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2022; 12:3836-48.

- Nematov D, Burhonzoda A, Khusenov M. First Principles Analysis of Crystal Structure, Electronic and Optical Properties of CsSnI3–xBrx Perovskite for Photoelectric Applications. J. Surf. Invest. 2021; 15:532–533. [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D.D. Kh.T. Kholmurodov, S.Aliona, K. Faizulloev, V.Gnatovskaya,T. Kudzoev, “A DFT Study of Structure, Electronic and Optical Properties of Se-Doped Kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTSSe),” Letters in Applied NanoBioScience, 2022, 12(3), p. 67.

- Nematov D, Makhsudov B, Kholmurodov Kh, Yarov M. Optimization Optoelectronic Properties ZnxCd1-xTe System for Solar Cell Application: Theoretical and Experimental Study. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2023; 13:90. [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D., Burhonzoda, A., Khusenov, M., Kholmurodov, K., Doroshkevych, A., Doroshkevych, N., ... & Ibrahim, M. (2019). Molecular dynamics simulations of the DNA radiation damage and conformation behavior on a zirconium dioxide surface. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry, 62(The First International Conference on Molecular Modeling and Spectroscopy 19-22 February, 2019), 149-161. [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D. D., Burhonzoda, A. S., Khusenov, M. A., Kholmurodov, K. T., & Ibrahim, M. A. (2019). The quantum-chemistry calculations of electronic structure of boron nitride nanocrystals with density Functional theory realization. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry, 62(The First International Conference on Molecular Modeling and Spectroscopy 19-22 February, 2019), 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Nizomov Z, Asozoda M, Nematov D. Characteristics of Nanoparticles in Aqueous Solutions of Acetates and Sulfates of Single and Doubly Charged Cations. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2022, 47, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, I., Gorban, O., Maksimchuk, P., Viagin, O., Malyukin, Yu., Gorban S., Volkova, G., Glasunova, V., Guadalupe Mendez-Medrano, M., Colbeau-Justin, Ch., Konstantinova, T., Lyubchyk, S. Photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanopowders: The role of production techniques in the formation of structural defects. Catalysis Today 2019, 328, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, I., Gorban, O., da Costa Zaragoza de Oliveira Pedro, P.M, Viegas, J., Shapovalova, O., Akhozov, L., Konstantinova, T., Lyubchyk S., Photocatalytic Composite Nanomaterial and Engineering Solution for Inactivation of Airborne Bacteria, Topics in Catalysis 2021, 64, 772–779. [CrossRef]

- Dilshod, N., Kholmirzo, K., Aliona, S., Kahramon, F., Viktoriya, G., & Tamerlan, K. (2023). On the Optical Properties of the Cu2ZnSn [S1− xSex] 4 System in the IR Range. Trends in Sciences, 20(2), 4058-4058. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, E. G., Shevchenko, Y. V., Snitsarev, V., Gorbach, V.V., Ragulya, A. V., Lyubchik, S. Features of superexchange nonresonant tunneling conductance in anchored molecular wires, AIP Advances 2019, 9, 115120. [CrossRef]

| mol. %Y2O3 | Zr | Y | O | O vacancy | System |

| 0 | 32 | 0 | 64 | 0 | Zr32O64 |

| 3.23 | 30 | 2 | 63 | 1 | Zr30Y2O63 |

| 6.67 | 28 | 4 | 62 | 2 | Zr28Y4O62 |

| 10.35 | 26 | 6 | 61 | 3 | Zr26Y6O61 |

| 16.15 | 22 | 10 | 59 | 5 | Zr22Y10O59 |

| Lattice constants | This work | Exp. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | SCAN | |||

| m-ZrO2 [P2_1/c] | a (Å) | 5.191 | 5.115 | 5.0950 [24] |

| b (Å) | 5.245 | 5.239 | 5.2116 [24] | |

| c (Å) | 5.202 | 5.304 | 5.3173 [24] | |

| β◦ | 99.639 | 99.110 | 99.230 [24] | |

| V (Å3) | 144.410 | 139.400 | 140.88 [24] | |

| t-ZrO2 [P4_2/nmc] | a=b (Å) | 3.593 | 3.622 | 3.6 4[25] |

| с (Å) | 5.193 | 5.275 | 5.27 [25] | |

| c/a | 1.445 | 1.456 | 1.45 [25] | |

| V (Å3) | 67.05 | 69.214 | 69.83 [25] | |

| dz | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.046 [25] | |

| c-ZrO2 [Fm-3m] | a=b=c (Å) | 5.075 | 5.12 | 5.129 [26,27] |

| V(Å3) | 130.709 | 134.06 | 134.9 [26,27] | |

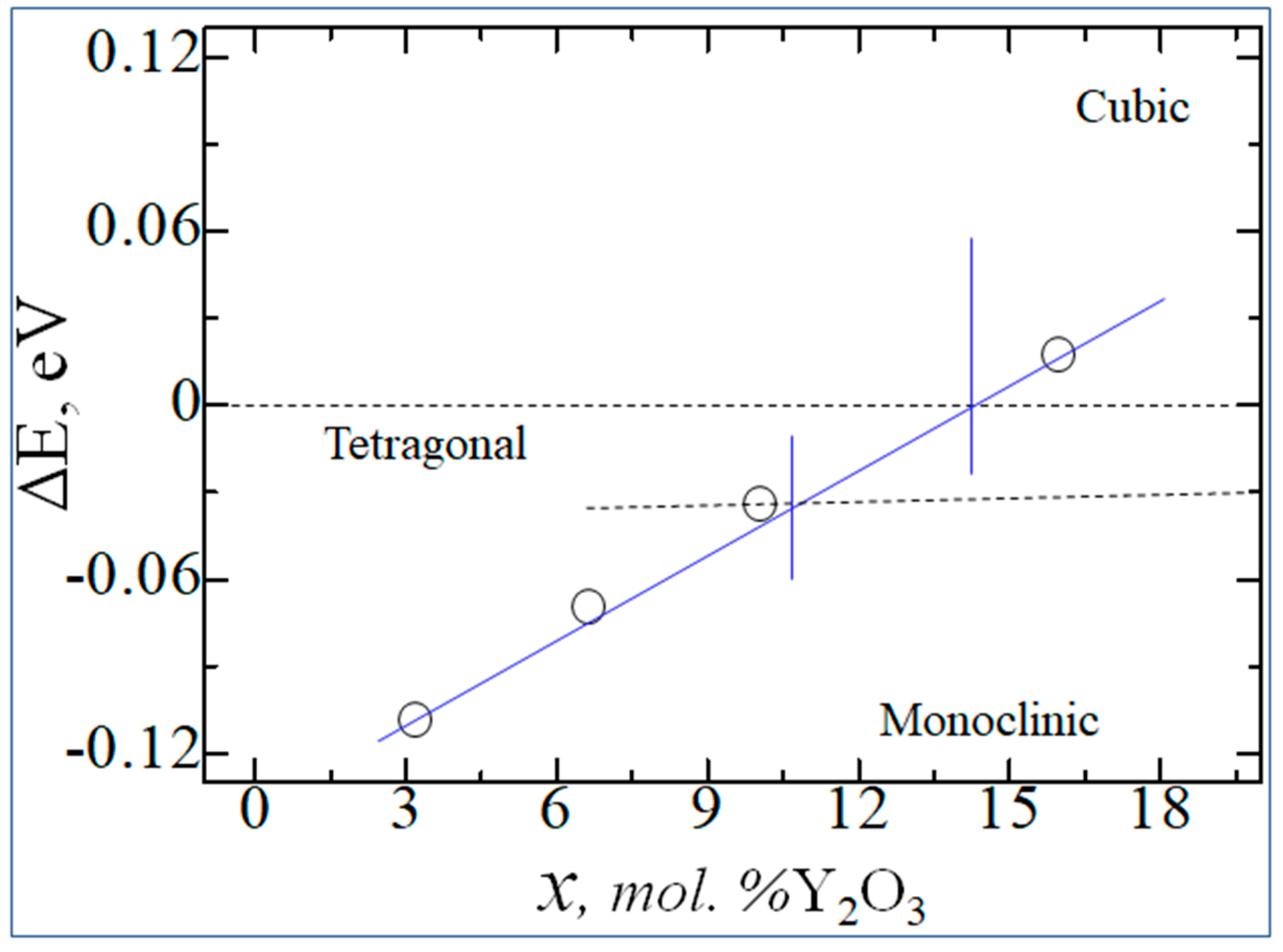

| System | Energy | ΔE |

| m-ZrO2 | -28.7947 | 0 |

| t-ZrO2 | -28.6885 | 0.106 |

| c-ZrO2 | -28.5865 | 0.201 |

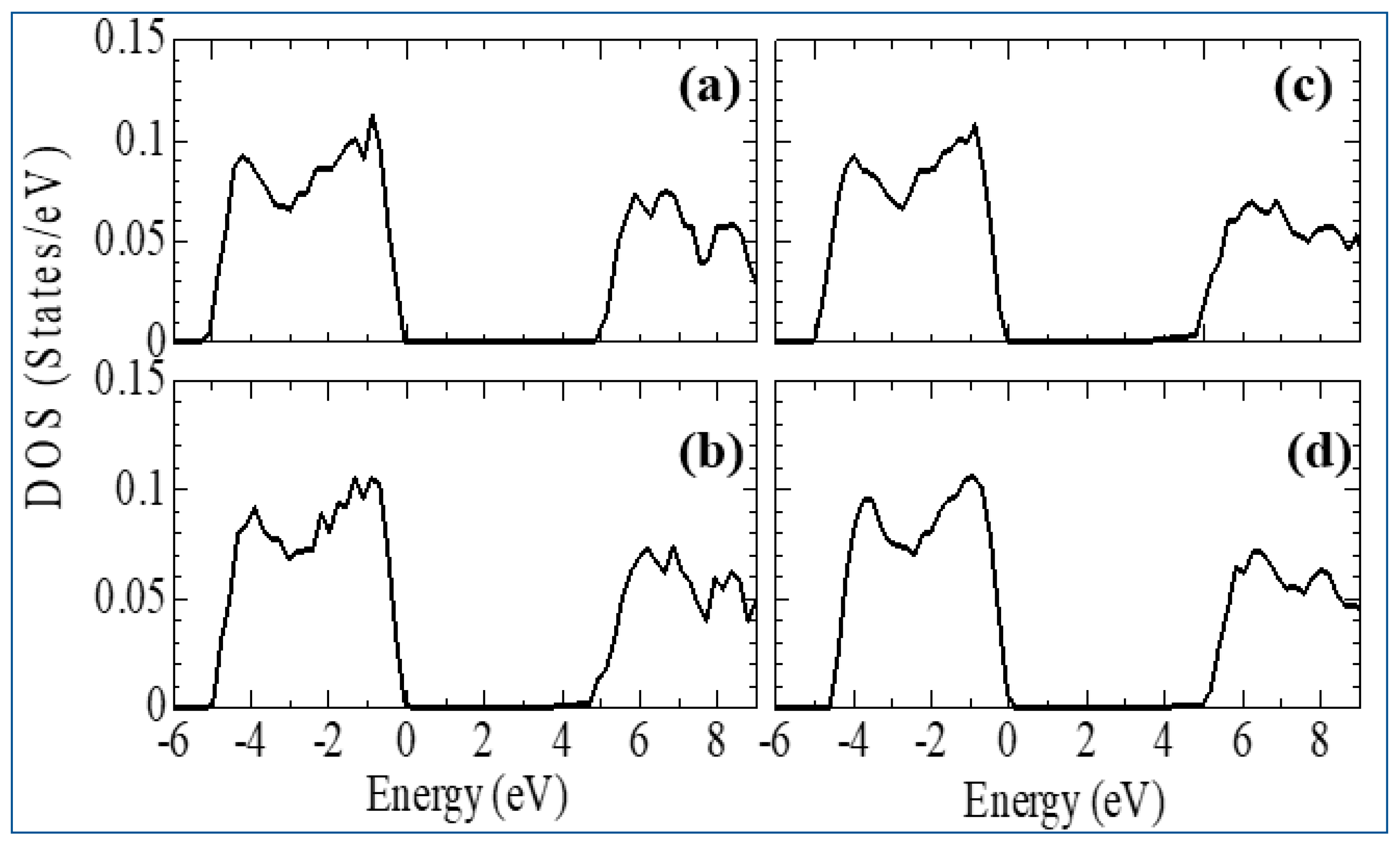

| System | This work | Experiment [30] | ||

| GGA | SCAN | HSE06 | ||

| m-ZrO2 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 5.288 | 5.78 |

| t-ZrO2 | 4.42 | 4.37 | 5.898 | 5.83 |

| c-ZrO2 | 4.03 | 3.93 | 5.140 | 6.10 |

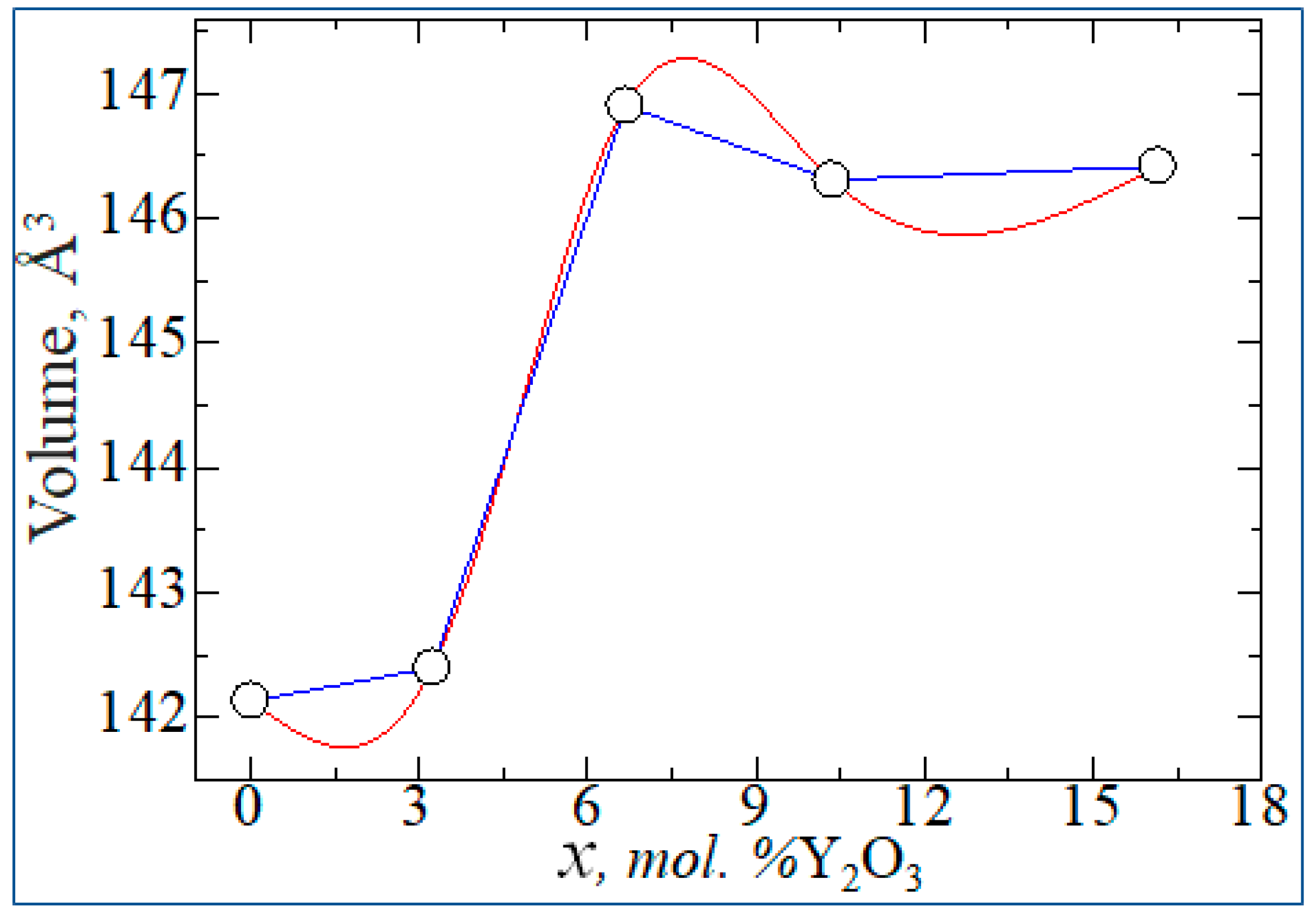

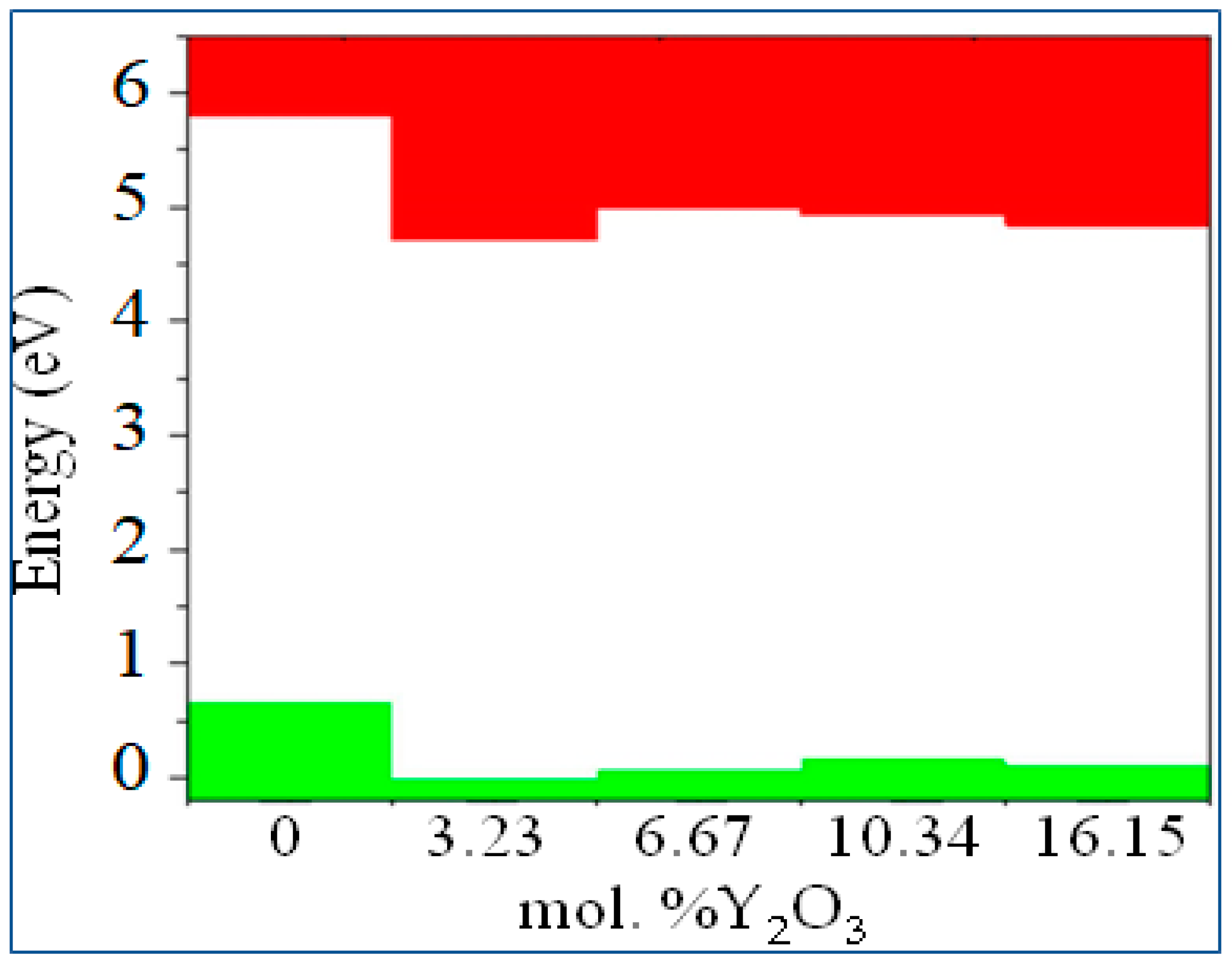

| System | Lattice parameters | Phase | |||||

| a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | α (◦) | β (◦) | γ (◦) | ||

| 0 | 10.23 | 10.478 | 10.608 | 90 | 99.64 | 90.00 | m - YSZ |

| 3.23 mol. %Y2O3 | 10.274 | 10.524 | 10.536 | 90.21 | 98.84 | 89.94 | m - YSZ |

| 6.67 mol. %Y2O3 | 10.512 | 10.544 | 10.603 | 89.90 | 90.12 | 89.62 | t - YSZ |

| 10.35 mol. %Y2O3 | 10.529 | 10.541 | 10.546 | 89.98 | 90.09 | 90.08 | t - YSZ |

| 16.15 mol. %Y2O3 | 10.540 | 10.541 | 10.543 | 90.08 | 90.00 | 90.02 | c - YSZ |

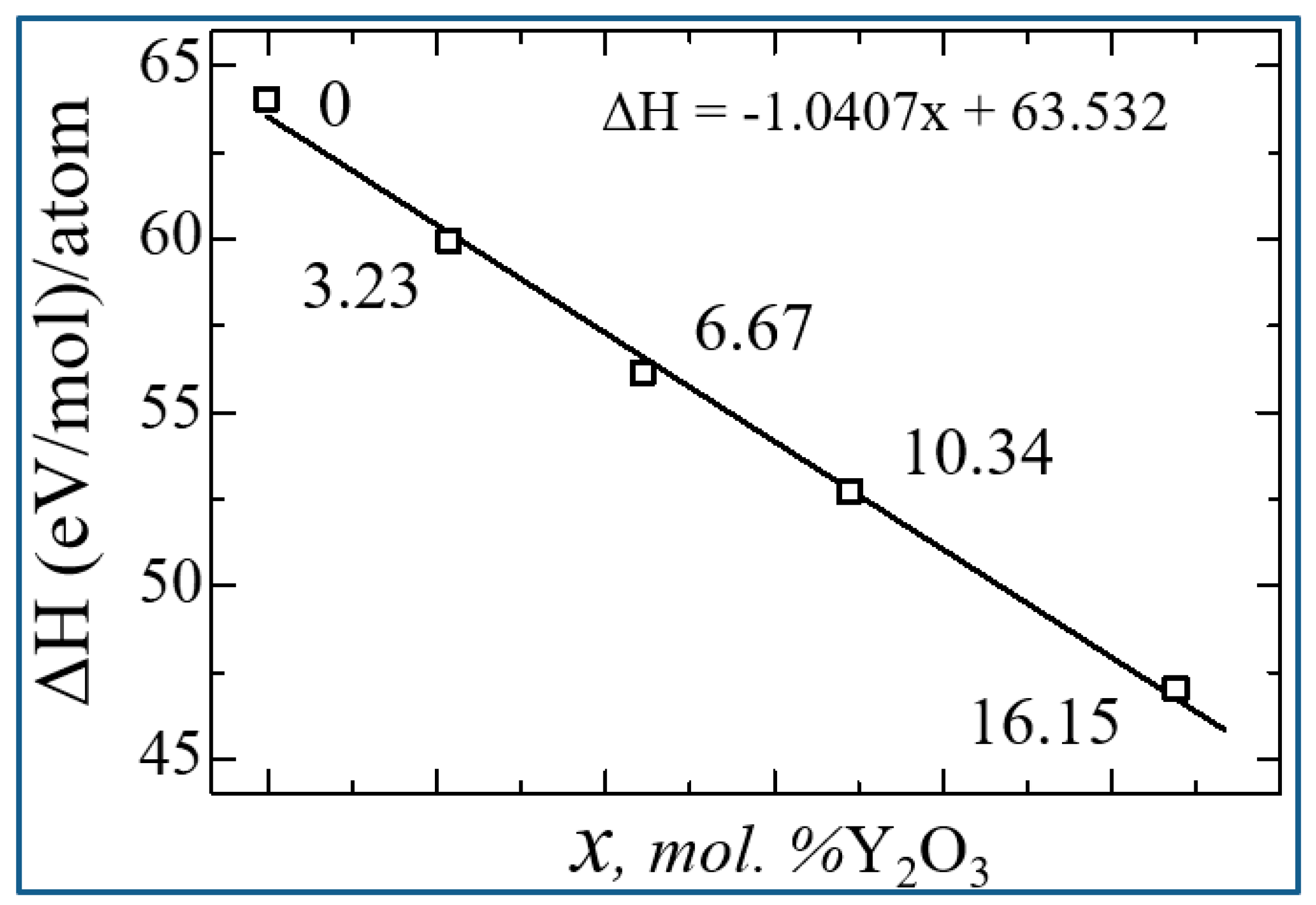

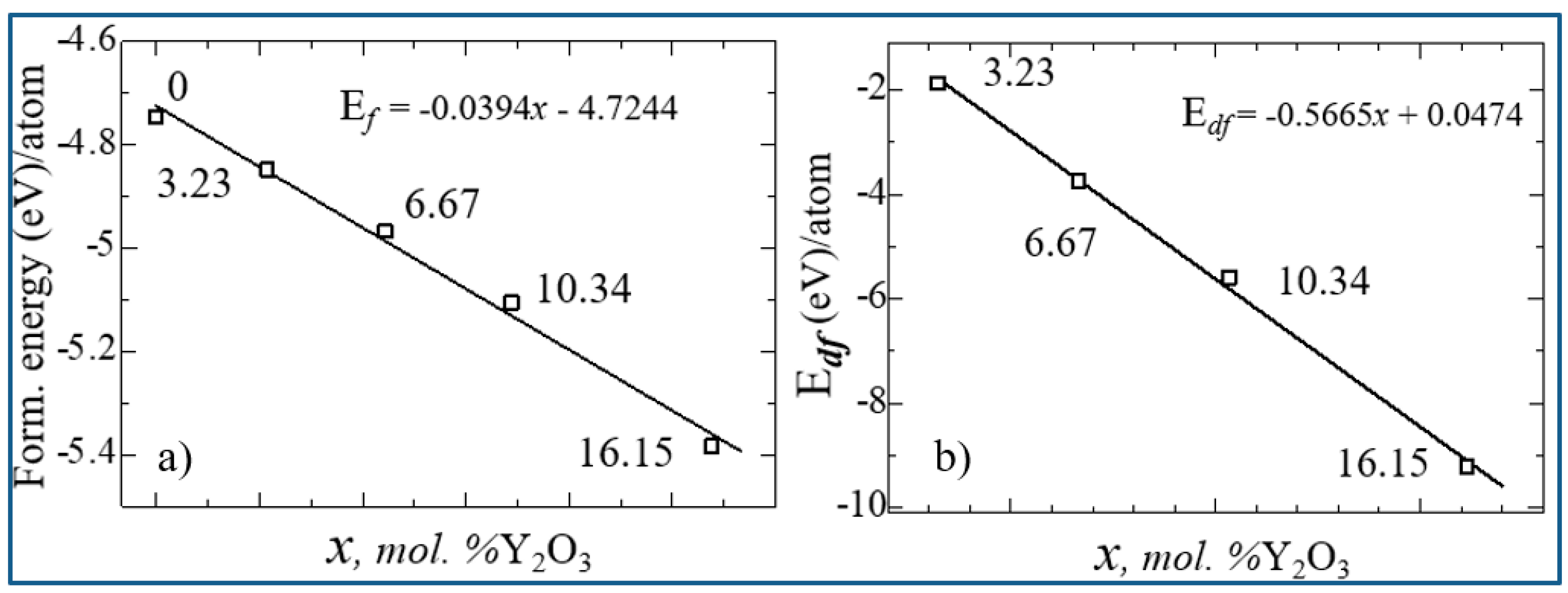

| System | ΔН | Еf | Еdf |

| 0 | 64.02917222 | -4.747216667 | 0 |

| 3.23 mol. %Y2O3 | 59.91124404 | -4.848422632 | -1.874577368 |

| 6.67 mol. %Y2O3 | 56.13271879 | -4.967857447 | -3.739875532 |

| 10.35 mol. %Y2O3 | 52.7041267 | -5.106527419 | -5.596013441 |

| 16.15 mol. %Y2O3 | 47.00229139 | -5.384704945 | -9.220196154 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).