I. Introduction and Context

Evidence shows persistent upward trends in development indicators in Bangladesh during the last four decades. Kausik Basu, the former World Bank Chief Economist, was amazed to see Bangladesh making remarkable progress in many economic and social indicators (Basu, 2018). On the contrary, Bangladesh performed consistently lower in all indicators of governance as shown in the Governance Matters report based on World Bank data (Kaufman, Kraay & Mastruzzi, 2010; Khan, 2015; Khan, 2013). This unconventional relationship between governance and development in Bangladesh has been characterized as the Bangladesh Conundrum (World Bank, 2011).

Education is one of the sectors echoing the same conundrum. In Bangladesh, many indicators have increased, like literacy levels, the female proportion of literacy, number of schools, colleges, universities, and technical institutions, availability of free course materials, etc. (ADB, 2008; World Bank, 2013). However, problems of mismanagement and mismanaged reforms remain a constant impediment (World Bank 2016). This poor management of reforms is also evident in ‘isomorphic mimicry’ of institutional reforms and excessive development showing much less impact, for example, schools are built but in which children do not learn (Pritchett, Woolcock & Andrews, 2013; Andrews, Pritchett & Woolcock, 2017).

While there are many studies from liberal arts point of view discussing the colonial context, history and impact on education sector in Bangladesh (for example, Chowdhury & Sarkar, 2018; Roshid, Siddique, Sarkar, Mojumder & Begum, 2015; Rahman, Hamzah, Meerah & Rahman, 2010), many other contemporary studies focused on particular levels and sub-sectors of education and or thematic area like ICT in education, English language in Education, etc. (For example, Siddik & Kawai, 2020; Rahman, Nakata & Nagashima, 2019; Kono, Sawada & Shonchoy, 2018; Khan, Hasan & Clement, 2012). These and other studies investigated the education sector from variety of important dimensions, interventions and associated statistics available. Despite all these, studies containing real life citizen experience and ground level realities are rare.

What is the citizen experience in the education sector? With this central question, the author started examining media reports. Author perused more than five leading newspapers and compiled a shortlist from many articles. Items with repeated nature were deliberately excluded and items of varied nature were included to illustrate the full range or collated view of the problem.

The objective was NOT to identify the statistical distribution of any particular type of problem (literacy rate, dropout rate, graduation rate, etc.) across the institutions or measure the attitude and perception of the people regarding education sector problems or conduct factor analysis. Rather, the objective is to understand the pattern, type, scope, and nature of education sector problems, which have become very common across the country and can be categorized ‘as a matter of management’ (or lack of it).

So many things improved in quantity, but qualitative improvement remained mysteriously low, despite government intention to increasing quality, along with quantity. Perennial gaps remain in the management of resources, including planning, implementation, monitoring, and strategic analysis of the basic problems in the education sector, like elsewhere. The assumption is if we can understand the problem from management and HRM perspectives, then the education sector problems can be resolved to a great extent.

II. Case Development Methodology

Since our objective is to understand in-depth, the nature of the problem, the qualitative approach was deemed appropriate (Creswell, 1994; Bryman & Bell, 2011; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2012). Case development is a particular type of qualitative approach where systemically detailed examination combines various methods of inquiry to understand the phenomenon within a particular context (Yin, 1994, 2003; Creswell, 1994; Scappens, 1990). Case study research not only explores but helps to understand the world within a particular context, uses multiple methods for collecting data.

In the present context, the education sector is a case where many instances of the education sector have been consolidated to understand the overall problem of management in governance for aiding understanding and analysis. This approach seemed more appropriate than another education sector-specific metrics study, which is abundant from government, non-government, and donor sources. To understand the main problems in the Bangladesh education sector, both primary and secondary information was gathered as follows:

Secondary: secondary sources, i.e. newspaper reports on education, from the 2010 – 2020 time period in two distinct phrases. Leading newspapers were randomly selected and articles related to education were selected up to the point that all levels of education and problems are represented in the sample.

Primary: field visits, observations, and citizen interviews were undertaken on-site and off the site.

An ethnographical approach was followed to understand the nature of the study problem (Yin, 2003; Creswell & Creswell, 2017). For example, living and observing in the setting for an extended period were done to build the case.

III. Analysis and Discussion: Secondary Sources

The first phase covered the period from 2009 – 2012 having a sample of reports from the leading dailies. We did the same for the current period, as of 2019, but did not repeat all types of problems, because most of these remained almost the same in nature; only the name of the district and sub-district (Upazila) might change. However, for the second phase, the study selected media reports from 2016 to 2020, relating to ‘teacher shortage’ to make the point that we needed to develop the ‘management’ view of the problem.

The first phase (2009-2012):

- -

People with qualifications of class v and class viii will run educational institutions (managing committee). Source: Prothom Alo, September 3, 2009

- -

12 govt. and 70 non-govt. schools have no headmasters in 9 upazilas in Noakhali district. Source: Daily Star, October 11, 2009

- -

Government plan special incentive for English teachers. Source: New Age, December 6, 2009:

- -

16,000 non-govt. primary school teachers are going to get special consideration. Source: Prothom Alo, July 19, 2009

- -

Most government schools run without headmasters and assistant headmasters. Source: Daily Star, July 23, 2009

- -

School running with only 1 teacher in Nandail, Mymensingh district. Source: Prothom Alo, April 1, 2010.

- -

67 teachers have been appointed with fake certificates in Kishoregonj district. Source: Prothom Alo, October 2, 2010.

- -

Bachelor (honors) course was introduced 12 years ago but no teacher has been appointed so far in Magura Government College. Source: Prothom Alo, March 23, 2010.

- -

Porshuram (Feni) Govt. College: No teacher available for nine subjects including English. Source: Prothom Alo, November 2, 2010

- -

Government loans to good but insolvent students on the anvil. Source: New Age, January 29, 2010.

- -

Primary education system in crisis: Bashkhali upazila, Chittagong district. Source: Daily Purbokone, March 8, 2011.

- -

Gohinkhali Govt. Primary School, Golachipa upazila (Potuakhali): No Headmaster for 12 years; Teaching going on by a hired teacher. Source: Prothom Alo, March 27, 2011.

- -

Only one teacher for 96 students at Brikbanupur (Raujan, Chittagong) Govt. Primary School. Source: Shamakal, April 19, 2011.

- -

The School at Sonadia, Moheshkhali (Cox’s Bazar District) is running with only one teacher. Source: Prothom Alo, February 24, 2011.

- -

Classes cancelled for Fair in the school playground, fair organized by political party student wing, vulgar show in the name of cultural programs. Source: Prothom Alo, March 11, 2011.

- -

Schools in the rural area face an acute shortage of English teachers. Source: Dhaka Mirror, March 15, 2011.

- -

Jarailtoli high school, Ramu upazila, Cox’s Bazaar district: 15 teachers and staff are not getting any salary for 3 months. Source: Prothom Alo, March 20, 2011.

- -

No female teachers in 50 govt. girls high schools in the country. Source: Amar Desh, April 19, 2011.

- -

Vandaria (Pirojpur district) government college: teacher shortage. Source: Kaler Kontho, February 28,2011.

- -

Tardy recruitment system keeps 3677 posts vacant in 253 colleges. Source: Daily Star, March 9, 2011.

- -

Teacher crisis at Chittagong University; some departments are having acute shortage; student-teacher ratio up to 46 to 1. Source: Jugantor, April 8, 2011.

- -

Department of computer science, Chittagong University: Teacher in study leave without approval for 5 years. Source: Prothom Alo, 2011.

- -

Waiting for President and Prime minister’s approval: More than 1500 medical college teachers are awaiting promotion after 8-10 years. Source: Jugantor, February 23, 2011.

- -

Intense Teacher Crisis in College of Leather Technology: requires 80 teachers, has only 6 teachers, new admission postponed. Source: Prothom Alo, 2011.

- -

Technical education has become certificate oriented due to crisis of teachers. Source: Prothom Alo, April 27, 2012.

Then we move to second phase media reporting and review the situation in the education sector management. In this phase we collect news items in the education sector during 2016 to 2020.

The second phase (2016-2020):

- -

College teacher shortage: The teachers must realize sincere execution of their duties is more important than trying to get city postings. Source: Independent, September 22, 2016.

- -

Teacher shortage plagues 60pc Bangladesh pry schools. Source: NewAge, July 6, 2018.

- -

Teacher shortage cripples public college in Feni: The institution—which has about 1500 enrolled students—is basically situated in an abandoned building, and there isn’t even a principal appointed. Source: Dhaka Tribune, July 4, 2019

- -

6500 teachers shortage in Chittagong Division; 1260 headmaster shortage. Source: Azadi, Sep 15, 2019

- -

Teacher-shortage hampers education in 13 Naogaon pry schools. Source: Financial Express, March 12, 2020.

- -

Teacher shortage hinders studies at century-old Bagerhat school. Source: UNB News, February 03, 2020.

Reports from the second phase show that the nature of the problem in the education sector, remained similar between ten years (2009 and 2019). For example, in the teacher shortage problem category, the basic problem of HR planning remained the same despite well-known, visible, and indicator-based improvements.

In the past, many non-government schools recruited teachers at low wages, whenever they needed. Now they demand nationalization from the government or at least MPO (monthly pay order, a budget allocation from government to pay the salary part of the teachers and some non-teaching staff) facility. Many of them actually are not qualified as per NTRA (national teachers’ recruitment authority) criteria. But they have been serving for many years and presumably providing low quality education. This is a problem of the regulatory environment of management in the education sector, talent acquisition problem, and a recruitment process within broader HRM (human resource management) within government bodies.

Ministers and Parliament Members promise informally about government intention to improve education and the facilities or conditions for all in the education sector. Sometimes that creates a negative impression in the end, due to a lack of coherent planning. In Management terms, this is a lack of coherent vision and activities or a lack of goal alignment. The government may not be skilled at managing the huge supply chain management task of supplying books and educational equipment and materials timely to all schools.

School buildings and premises get destroyed in cyclones, floods, and other disasters. It takes time to repair and rebuild them. The Government cannot claim to have any sound prioritization mechanism in place. And needless to mention, it is more procedure-oriented rather than crisis management oriented.

Even government teachers with government pay scale and other benefits are not interested to work in rural and remote areas, due to communication difficulties and lack of amenities. One the one hand, there is a lack of job rotation, transfer, and promotion mechanisms. On the other hand, compensatory wage mechanism is not in practice that rewards or compensate for ‘unpleasant work conditions’.

In a diverse education sector, retirement is a usual phenomenon. Vacancies are created and it takes time and process to fill those vacancies. On the surface, it may appear that there is a huge competition and a long queue for teaching jobs. But there are perennial problems of 'teacher shortages’ at every level of educational institutions. But this ‘staffing’ need is very much predictable and is a routine HRM (human resource management) issue for the education sector. However, government agencies do not seem to have this basic capability of HRP (Human Resource Planning), or managing the HRP process, that keep many schools in perennial shortage of teachers and even, headmasters. There is hardly any effective succession planning to fill up the vacancies.

Apart from ‘recruitment’ and ‘training’, motivation is a major problem in the education sector. It may seem like there is huge interest for teaching jobs. But on the job, lack of motivation is found to be an everyday problem. Teachers are not present in the schools, or not committed to their ‘regular’ classes, administrative monitoring is poor, and all sorts of demotivating behaviors are observed. That means these recruits are not ‘teachers by choice’. They just wanted the ‘government job’ and lifetime employment, sometimes even with the help of corrupt officials and school management committee members. This is a problem of assessment tool or recruitment and selection procedure, ending up in poor placement or position filling. And there are hardly any On-the-job-Training or Off-the-job training that can address the psychological issues of position placementto improve their intrinsic motivation of the job itself.

IV. Analysis and Discussion: Primary Sources, Citizen Experiences

In parallel to analyzing secondary sources, we observed the instances from the social setting and conducted citizen interviews at appropriate places to develop the narratives about the 'problem' related to the 'education sector from the citizen perspectives.

In line with the objective of insight-rich observations, non-probability sampling were deployed. This required small sample (here around twenty citizen participants), but with logical relationship and with purpose (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2012) for site visits and interview to generate theoretical saturation from theoretical sampling as evident in grounded theory approach, where researchers collects, codes, and analyzes the data from the ground, simultaneously (Glaser & Strauss, 2014, 2017). Thus, rather than the sample size, theoretical saturation is more important, a situation when no significantly new and relevant data is left for further sampling (Bryman & Bell, 2011; Saunders et al., 2012).

Following is a narrative summary and analysis of citizen discourse on the education sector:

Coaching centers: Without coaching centers education has become unthinkable. Certain students need extra ‘help’ beyond regular school classes. Going to teachers who are knowledgeable in that subject has been around in our country for a long time. However, the form of ‘coaching’ as seen today is not a desired one by the citizens.

From the citizen’s survey, it emerged that among the problems people are facing in the education sector, the pervasiveness of coaching centers is the most significant one. Whether it is the urban or rural area, male or female, good school or ordinary school, lower-level classes or upper level, ‘coaching culture’ has been included with mainstream education as an important and undeniable requirement.

From pre-school to high school admission coaching, cadet college coaching, to ‘all class all subject-based coaching', PECE (class 5) coaching, JSC (class 8) coaching, SSC (class 10) coaching, HSC coaching, etc. are common elements of today’s education scenario. After HSC, there is admission test coaching: medical, engineering, university different units (A, B, C, D, etc. At the university level, there is subject coaching, mainly for many national university (NU) degree programs. In many cases, for public and private universities, etc. there are established subject-based coaching centers (for example, mathematics, statistics, accounting, economics, etc.)

Admission hassle in the few good schools: There are only a few good schools in major cities and towns. From taking admission form, admission coaching (often under a school teacher), taking the children to schools for admission tests, getting them back after the test, admission formalities, fees, etc. are common hassles faced by guardians and prospective students.

Total seats in all schools are not short compared with total demand. But yet people and parents undergo this hassle because, most of the schools, government or private, are of low quality and show ordinary performance, year after year. The Government was unable to do anything to change the ranking of the schools. The same schools do better for years; new schools do not get better. Which ultimately make guardians scramble for good schools.

No quality control in teaching: The concept of quality in education is vague. Is it good teacher, good students, good system, good SSC, HSC results? In most cases, the teacher’s salary is very poor. In some private schools run like a for profit business, earn a huge amount from the students in forms of tuition fee, school dress, stationeries, etc., the teachers’ salary structure is low due to a surplus in the labor supply. So the teaching profession does not attract better-qualified people and is unable to motivate the existing ones.

Teacher shortage in English, Maths, Science: Many educated youths are unemployed. On the other hand, there are vacant posts in the schools due to a long, bureaucratic recruitment procedure. Add to that low remuneration levels, and as a result, better human resources are not available in the education sector. This phenomenon becomes more visible when it comes to subjects like English, Math, and Science.

The urban-Rural disparity in education quality: Though Bangladesh is a developing country, there have been reputed schools and colleges in rural and district towns since the British period. From these schools and colleges graduated renowned personalities of present times. But now the situation is different. Good graduates are not produced from rural areas except in a number of statistical outlier institutions.

Poor service experience with education boards: Students and parents have to visit the education boards for many reasons. For example, correcting student name, father's name, mother's name, and other spelling mistakes in the certificates, etc. There is the case of delay and procrastination, and rent-seeking behavior of the staff. However, nowadays many services have become digital.

Opening and Running private (non-government) schools: For Bangladesh, it is difficult for the Government to provide public education (government schools) for all students. So, private sector participation is encouraged in principle. But when a potential school promoter goes to the education board, he finds no one-stop guideline. One has to depend on the whims of the officials. Private sector parties have to ‘manage’ the officials and procedural bureaucracy. The environment discourages compliance and encourages malpractice. So schools in the private sector (non-government schools) are opened and run by profit minded investors, with little orientation with education.

Notebook or Guidebook Confusion: At different times, the Government banned notebooks or guidebooks in the market. Sporadically the Government conducted ‘mobile courts’ (regulatory drive) to seize the guidebooks from bookshops and penalize the sellers. But it is there in the market all year round. Many guidebooks are of a high standard. Those help to supplement or complement the textbooks, which are perceived to be of the lower standard at times. Some notebooks are of so poor quality that it needs a regulatory authority to penalize them. Parents and students do not think it is a good idea to ban the guidebooks.

Governance and general mismanagement of the institutions: Governance and managing committees, if there are any, are only in paperwork and bureaucracy. Most educational institutions do not have any sound governance and management mechanism considering all stakeholders into account. In many cases, these are just pocket committees or country club committees of politicians, businessmen, and a few influential local people. So mismanagement of school administration, logistics, and the fund is very common. This management problem can be consolidated as follows: The institutions do not provide sufficient logistic facilities for the students. They cannot ensure the quality of teaching and the teachers. They do not provide good salaries to teachers because due to the common thinking that many unemployed young graduates are easy to find with minimal salaries. The private and for profit schools charge tuition and other fees at their will and also increase them annually at will. They do not entertain the voices of parents, students, and teachers. In a word, they do not have sound management and governance mechanism.

V. Policy Implication: A More Management Problem than Budget or Education Issues

The objective of this paper was to draw an overall picture of the problems prevalent in the education sector, and see how those fall into the ‘management’ category. Most of the people working in the education sector, media, and many citizens quickly assumed and concluded that the main problem of education sector is budget as a percentage of GDP (gross domestic product – a measure of national income), that means lack of sufficient fund allocation in the education sector. But according to our observation and analysis, many cases are simply due to not knowing ‘how to manage the available fund’ effectively and efficiently.

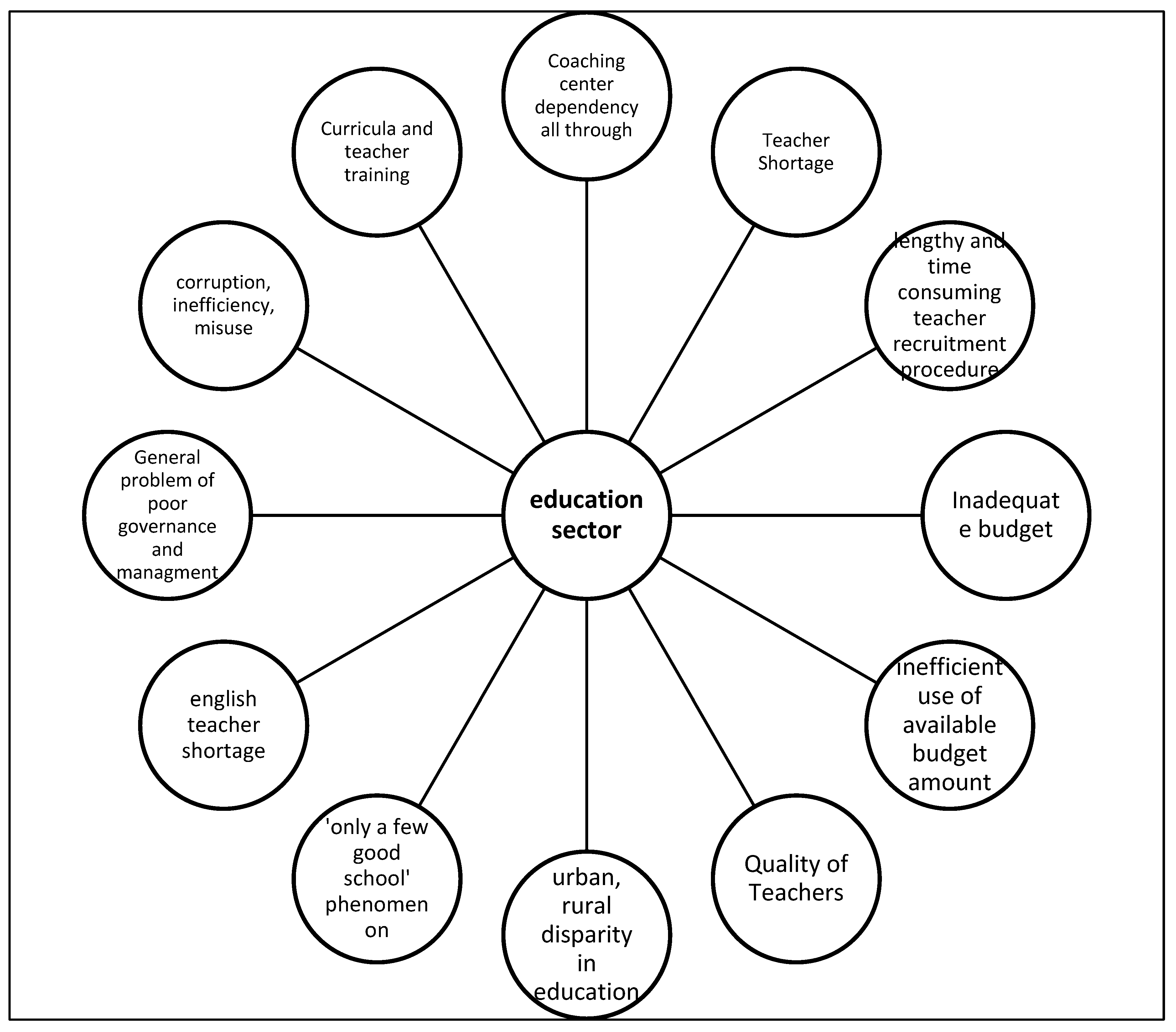

As seen in the

Figure 1, there are many problems in education sector or the education sector problems have many dimensions. The problems are very much well-known and repetitive. It is not problem number one, two, and three, and so on. There are

multiple dimensions of a single problem. Again,

multiple problems have a common dimension. So it is better to show as a circular network diagram rather than a numbered list.

Management in the Government seems to be lacking managerial acumen in managing the process, system, and structure. Education sector is just one case. For example, managing the process of teacher recruitment, training, retirement, and staffing the vacant positions. We observed that there are many ‘authorities’ in the education sector – education board, Education Office (thana office, district office, up to Education Directorate), DC office (deputy commissioner, Jela Proshashok, in Bangla), Divisional Commissioner office, etc. All are needed for reasons, whatsoever. However, there are inconsistencies, overlapping, and incoordination in their work scope and approaches. There is a clear need of ‘coordination’ and ‘collaboration’, which, again, are the matters of ‘management’, not of education budget or teaching methods problems.

On the part of public management or management in government in the education sector, from ministry to directorates to institution level, we need a greater understanding of the sector and citizen level problems.

VI. Conclusion and Further Research

The paper is qualitative and subjective in nature, but it contains thick descriptions of the scenario, which is not possible in the indicator or figure-based descriptive studies. There are many indicator-based studies and discussions in the area of education in Bangladesh, and most of them show quantity in progress. But at the next level, we need to take a look at the quality, in line with SDG 4 (sustainable development goal number 4) Quality Education for All, amid ‘tensions, challenges, and opportunities within SDG 4’ (Wulff, 2020). COVID pandemic made it even more imperative (Spiteri, 2021). It is a ‘responsibility shared’ among individuals, education and training institutions, and regulating governments (Boeren, 2019).

This case-based exploratory study may lead to further inquiry. For example, how to differentiate management factors and other factors like political, social, and cultural; Can management be improved without other factors or the other factors in place as it is; what could be an implementable management framework for improving qualitative dimension in the education sector; how to reduce the negative impact of political pressures in recruitment and overall HRM (human resource management) in the education sector, how to strategize in different phases in different subsectors of education – primary, secondary, higher secondary, tertiary, technical; and so on.

Bottom line is, management needs to be technically understood and appreciated by the Government, Education Ministry, Education Department and directorates, and citizens. We cannot expect a sustainable solution to the problem without a qualitative understanding of management (or lack of it) issues. Only increasing institutions, increasing teachers or manpower, or increasing their salaries and scales, will not systemically improve quality or solve education sector problems. We need a closer, comprehensive, holistic, and strategic look at the bottom. Further research as mentioned above, can help in that direction.

References

- ADB (2008). Education Sector in Bangladesh: What Worked Well and Why under the Sector-Wide Approach?. Washington, D.C.

- Andrews, M., Pritchett, L., & Woolcock, M. (2017). Building state capability: Evidence, analysis, action. Oxford University Press.

- Basu, K. (Apr 23, 2018). Why Is Bangladesh booming? Retrieved from https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/bangladesh-sources-of-economic-growth-by-kaushik-basu-2018-04.

- Boeren, E. (2019). Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “quality education” from micro, meso and macro perspectives. International Review of Education, 65(2), 277-294. [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2011). Business research methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chowdhury, R., & Sarkar, M. (2018). Education in Bangladesh: Changing contexts and emerging realities. Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2014). Applying grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 13(1), 46-50.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Kaufman, D., Kraay, A. R. A. T., & Mastruzzi, M. A. S. S. I. M. O. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Khan, A. A. (2015). Gresham's law syndrome and beyond. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

- Khan, M. M. (2013). Administrative reforms in Bangladesh. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

- Khan, M. S. H., Hasan, M., & Clement, C. K. (2012). Barriers to the introduction of ICT into education in developing countries: The example of Bangladesh. International Journal of instruction, 5(2).

- Kono, H., Sawada, Y., & Shonchoy, A. S. (2018). Primary, secondary, and tertiary education in Bangladesh: achievements and challenges. Economic and Social Development of Bangladesh: Miracle and Challenges, 135-149. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, L., Woolcock, M., & Andrews, M. (2013). Looking like a state: techniques of persistent failure in state capability for implementation. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., Hamzah, M. I. M., Meerah, T., & Rahman, M. (2010). Historical Development of Secondary Education in Bangladesh: Colonial Period to 21st Century. International education studies, 3(1), 114-125. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T., Nakata, S., Nagashima, Y., Rahman, M., Sharma, U., & Rahman, M. A. (2019). Bangladesh tertiary education sector review. [CrossRef]

- Roshid, M. M., Siddique, M. N. A., Sarkar, M., Mojumder, F. A., & Begum, H. A. (2015). Doing educational research in Bangladesh: Challenges in applying Western research methodology. In Asia as method in education studies (pp. 129-143). Routledge.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd/Pearson.

- Scappens, R. W. (1990). Researching management accounting practice: The role of case study methods. British Accounting Review, 22, 259-81. [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M. A. B., & Kawai, N. (2020). Government Primary School Teacher Training Needs for Inclusive Education in Bangladesh. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 16(2), 35-69.

- Spiteri, J. (2021). Quality early childhood education for all and the Covid-19 crisis: A viewpoint. Prospects, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

- World Bank. (2011). Governance matters. Washington, D.C.

- World Bank. (2013). Bangladesh Education Sector Review - Seeding Fertile Ground: Education That Works for Bangladesh. Washington, D.C.

- World Bank. (2016). Bangladesh: Ensuring Education for All Bangladeshis. https://www.worldbank.org /en/results/2016/10/07/ensuring-education-for-all-bangladeshis. Retrieved on September 15, 2019.

- Wulff, A. (2020). "Chapter 1 Introduction". In Grading Goal Four. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).