Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Teacher Professional Identity

1.2. Teacher Leadership and Extended Professionality

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Research Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlations

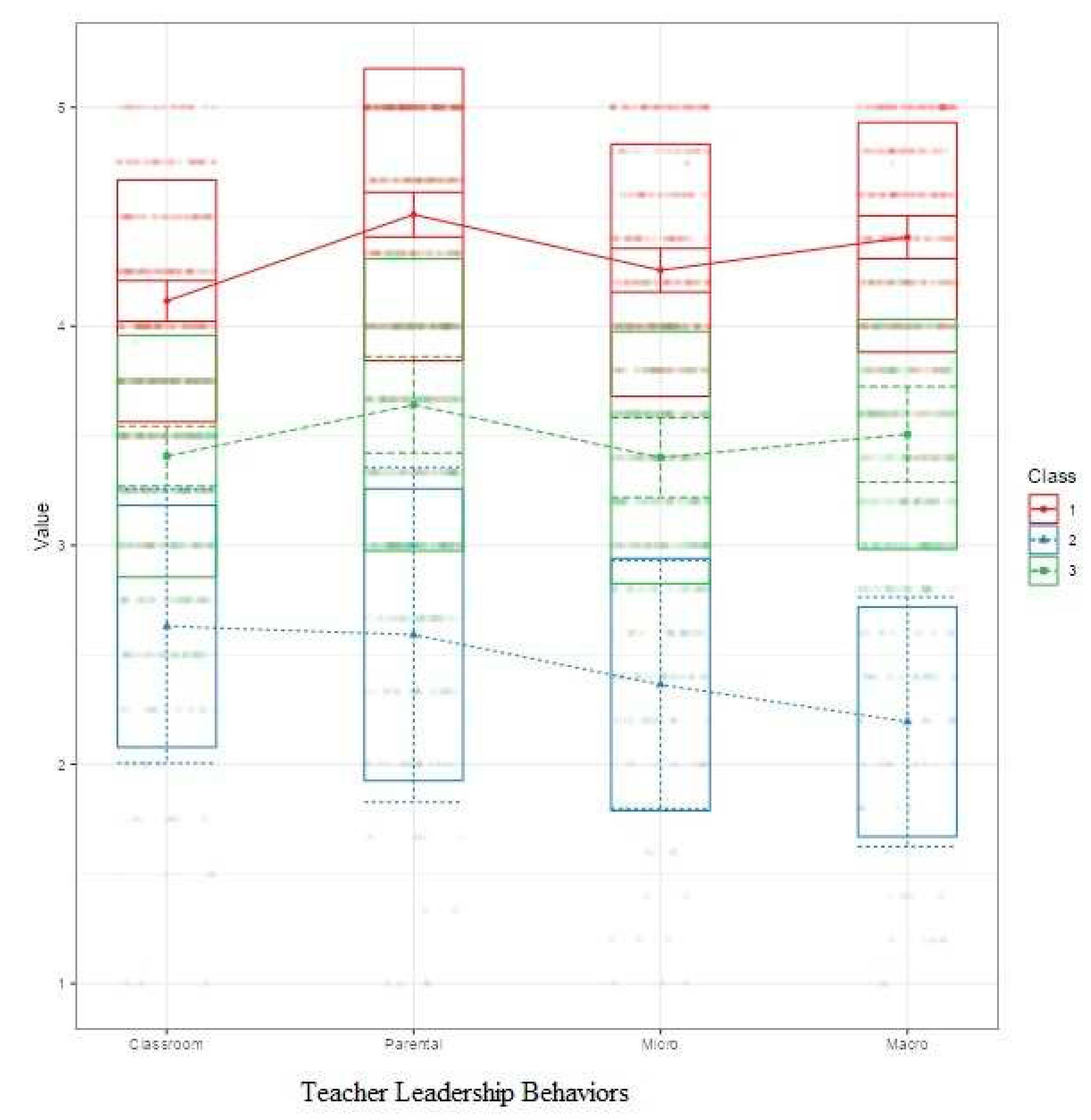

3.2. Profiles of the Teacher Leadership Behaviors

3.3. The Univariate Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Teacher Self-Efficacy Self Esteem Scale and Openness to Authority of Teachers.

4. Discussion

4.1. Suggestions and future directions for research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoyle, E. Professionality, professionalism and control in teaching. London Educational Review 1974, 3, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.P. Distributed leadership theory for investigating teacher librarian leadership. International Association for Librarianship. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrou, A.; Swaffield, S. (Eds.) Teacher leadership and professional development; Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hilty, E. B. (Ed.) Teacher leadership – the “new” foundations of teacher education; Peter Lang, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schott, C.; van Roekel, H.; Tummers, L.G. Teacher leadership: A systematic review, methodological quality assessment and conceptual framework. Educational Research Review 2020, 31, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. From professional practice to practical leader: Teacher leadership in professional learning communities. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 2016, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.W. The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers' professional relations. Teachers College Record 1990, 91, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Strengthening the Teaching Profession. Teacher leadership skills framework. Available online: http://cstp-wa.org/cstp2013/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Teacher-Leadership-Framework.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Leithwood, K.; Patten, S.; Jantzi, D. Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educational Administration Quarterly 2010, 46, 671–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, A. A Learning Odyssey: The trials, tribulations and successes of the educational institute of Scotland’s further education and teacher learning fepresentatives. Research in Post-Compulsory Education 2015, 20, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wu, H.; Reeves, P.; Zheng, Y.; Ryan, L.; Anderson, D. The association between teacher leadership and student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 2020, 31, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunzicker, J.L. Is it teacher leadership? Validation of the five features of teacher leadership framework and self-determination guide. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 2022, 11, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza, M.N. Defining teacher leadership: Affirming the teacher leader model standards. Issues in Teacher Education 2015, 24, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenmeyer, M.; Moller, G. Awakening the sleeping giant: Helping teachers develop as leaders; Corwin Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, S.; Markholt, A. Leading for instructional improvement: How successful leaders develop teaching and learning expertise; John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium. Teacher Leader Model Standards. 2012. Available online: https://www.nea.org/resource-library/teacher-leader-model-standards (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Smulyan, L. Symposium introduction: Stepping into their power: The development of a teacher leadership stance. Schools 2016, 13, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D. HertsCam: A teacher-led organisation to support teacher leadership. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 2018, 9, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wenner, J.A.; Campbell, T. The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A Review of the literature. Review of Educational Research 2016, 87, 134–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, A.; Newton, P.; da Costa, J. From teachers to teacher-leaders: A case study. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 2013, 4, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, V. The HertsCam teacher led development work program. In Transforming education through teacher leadership; Frost, D., Ed.; LfL: Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bangs, J.; Frost, D. Non-positional teacher leadership: Distributed leadership and self-efficacy. In Flip the System; Routledge, 2015; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, J.; Huggins, K.S. Distributed but undefined: New teacher leader roles to change schools. Journal of School Leadership 2012, 22, 953–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.Y.; Gimbert, B.; Nolan, J. Sliding the door: Locking and unlocking possibilities for teacher leadership. Teachers College Record 2000, 102, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.; Byrd, A.; Wieder, A. Teacherpreneurs: Innovative teachers who lead but don't leave; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carrion, R.G.; García-Carrión, R. Transforming education through teacher leadership. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management 2015, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L. A framework for shared leadership. Educational Leadership 2002, 59, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D.; Durrant, J. Teachers as leaders: Exploring the impact of teacher-led development work. School Leadership & Management 2002, 22, 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, B.; Doucet, A.; Owens, B. Teacher leadership in the aftermath of a pandemic: The now, the dance, the transformation. Independent report written to inform the work of Education International. Available online: https://issuu.com/educationinternational/docs/2020researchcovid19nowdancetransformation?fr=sZDU1MzE0MTkwMTA (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Ding, Z.; Thien, L.M. Assessing the antecedents and consequences of teacher leadership: A partial least squares analysis. International Journal of Leadership in Education 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunzicker, J. From teacher to teacher leader: A conceptual model. International Journal of Teacher Leadership 2017, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.L. Transforming identities: The transition from teacher to leader during teacher leader preparation. Journal of Research on Leadership Education 2016, 11, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helterbran, V.R. Teacher leadership: Overcoming 'I am just a teacher' syndrome. Education 2010, 131, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Beijaard, D. Learning teacher identity in teacher education. In The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education; Clandinin, D. J., Husu, J., Eds.; Sage, 2017; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman, S. F.; Meijer, P. C. A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 2011, 27, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Verloop, N.; Vermunt, J.D. Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education 2000, 16, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.Y. Pre-service and beginning teachers' professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education 2010, 26, 1530–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahan, P.L. Work environment stressors, social support, anxiety, and depression among secondary school teachers. AAOHN Journal 2010, 58, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclure, M. Arguing for your self: Identity as an organizing principle in teachers’ jobs and lives. British Educational Research Journal 1993, 19, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, P.S.; Serpe, R.T.; Stryker, S. Role-specific self-efficacy as precedent and product of the identity model. Sociological Perspectives 2018, 61, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper-Giveon, A.; Shayshon, B. Educator versus subject matter teacher: The conflict between two sub-identities in becoming a teacher. Teachers and Teaching 2017, 23, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. Teacher education and the development of professional identity: Learning to be a teacher. In Connecting policy and practice: Challenges for teaching and learning in schools and universities; Denicolo, P., Kompf, M., Eds.; Routledge, 2005; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Mogarro, M.J. Student teachers’ professional identity: A review of research contributions. Educational Research Review 2019, 28, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, E.; John, P. Professional Knowledge and Professional Practice; Cassell: London, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen, K.; Sleegers, P.; Bergen, T.; Klaassen, C. Professional orientations of secondary school teachers towards their work. Teaching and Teacher Education 2001, 17, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qanay, G.; Frost, D. The teacher leadership in Kazakhstan initiative: Professional learning and leadership. Professional Development in Education 2022, 48, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D. Identity-based motivation: Implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2009, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Jin, T. Teacher professional identity and the nature of technology integration. Computers & Education 2021, 175, 104314. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Geertshuis, S. Professional identity and the adoption of learning management systems. Studies in Higher Education 2021, 46, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, E. Changing conceptions of teaching as a profession: Personal reflections. In Professional Knowledge and Professional Practice; Hoyle, E., John, P. D., Eds.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jongmans, K.; Biemans, H.; Beijaard, D. Teachers' professional orientation and their involvement in school policy making: Results of a Dutch study. Educational Management & Administration 1998, 26, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D. The concept of ‘agency’in leadership for learning. Leading & Managing 2006, 12, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Collay, M. Discerning professional identity and becoming bold, socially responsible teacher-leaders. Educational leadership and administration: Teaching and Program Development 2006, 18, 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Poekert, P.; Alexandrou, A.; Shannon, D. How teachers become leaders: An internationally validated theoretical model of teacher leadership development. Research in Post-Compulsory Education 2016, 21, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A.; Friedrich, L. D. How teachers become leaders: Learning from practice and research. Series on school reform; Teachers College Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gaikhorst, L.; Beishuizen, J.J.; Zijlstra, B.J.; Volman, M.L. Contribution of a professional development program to the quality and retention of teachers in an urban environment. European Journal of Teacher Education 2015, 38, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, C. Irish teachers’ experience of professional development: Performative or transformative learning? Professional Development in Education 2011, 37, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akogul, S.; Erisoglu, M. An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy 2017, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, Ö. Öğretmen Liderliği Davranış Ölçeği: Geçerlilik ve Güvenilirlik Çalışması. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Buca Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 2023, 56, 1033–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: the role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology 1998, 83, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C.; Feldlaufer, H.; Eccles, J.S. Change in teacher efficacy and student self-and task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology 1989, 81, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg. 1965.

- Bolat, Ö.; Antalyalı, Ö.L. PS kişisel eğilimler envanterinin psikometrik özellikleri. Turkish Studies - Education 2023, 18, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from MRAN snapshot 2022-01-01).

- osenberg, J., Beymer, P., Anderson, D., Van Lissa, C.; Schmidt, J. tidyLPA: Easily Carry Out Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) Using Open-Source or Commercial Software. [R package]. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyLPA.

- Degnan et al., 2008.

- Williams, G.A.; Kibowski, F. Latent class analysis and latent profile analysis. Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods 2016, 15, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Annals of Statistics 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory; Petrov, B. N., Csaki, F., Eds.; Akademiai Kiado, 1973; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J. A primer to latent profile and latent class analysis. In Methods for Researching Professional Learning and Development: Challenges, Applications and Empirical Illustrations; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Variable-specific entropy contribution. Technical appendix. Muthen & Muthen 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, C.A.; Willoughby, T. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A latent class analysis among young adults. PloS one 2013, 8, e59955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, M. De professionele ontwikkeling van leerkrachten basisonderwijs. De spanning tussen autonomie en collegialiteit (Professional development of primary school teachers. The tension between autonomy and collegiality). Dissertation, University of Leuven, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. M.; Landman, J. “Sometimes bureaucracy has its charms”: The working conditions of teachers in deregulated schools. Teachers College Record 2000, 102, 85–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chval, K.B.; Arbaugh, F.; Lannin, J.K.; van Garderen, D.; Cummings, L.; Estapa, A.T.; Huey, M.E. The transition from experienced teacher to mathematics coach: Establishing a new identity. The Elementary School Journal 2010, 111, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. L. Getting recognized: Teachers negotiating professional identities as learners through talk. Teaching and Teacher Education 2010, 26, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Adams, A.; Bondy, E.; Dana, N.; Dodman, S.; Swain, C. Preparing teacher leaders: Perceptions of the impact of a cohort-based, job-embedded, blended teacher leadership program. Teaching and Teacher Education 2011, 27, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Classroom leadership | — | |||||||

| 2. Parental leadership | .53*** | — | ||||||

| 3. Micro-level leadership | .51*** | .45*** | — | |||||

| 4. Macro-level leadership | .52*** | .54*** | .64*** | — | ||||

| 5. Job satisfaction | .40*** | .33*** | .31*** | .38*** | — | |||

| 6. Teacher self-efficacy | .50*** | .42*** | .37*** | .46*** | .51*** | — | ||

| 7. Self esteem | .45*** | .36*** | .37*** | .37*** | .50*** | .53*** | — | |

| 8. Openness to authority | .36*** | .28*** | .32*** | .45*** | .29*** | .33*** | .44*** | — |

| The Number of Profiles | BIC | AIC | AWE | CLC | KIC | SABIC | Entropy | BLRTP | Profile size | Sample<5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6888 | 6852 | 6963 | 6838 | 6863 | 6863 | - | - | 710 | No |

| 2 | 6224 | 6165 | 6347 | 6140 | 6181 | 6183 | 0.77 | p<0.01 | 447,263 | No |

| 3 | 6018 | 5936 | 6189 | 5902 | 5957 | 5961 | 0.80 | p<0.01 | 341,54,254 | No |

| 4 | 5956 | 5851 | 6175 | 5807 | 5877 | 5883 | 0.78 | p<0.01 | 316,11,104,279 | Yes |

| Variables | Class | Mean score | Df | F | p | Eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction | extended professionality | 4,1946 | 2 | 62,793 | .000*** | 0,151 |

| restricted professionality | 3,1751 | |||||

| intermediate professionality | 3,7845 | |||||

| Teacher Self-Efficacy | extended professionality | 4,1232 | 2 | 96,071 | .000*** | 0,214 |

| restricted professionality | 3,2871 | |||||

| intermediate professionality | 3,7249 | |||||

| Self Esteem Scale | extended professionality | 5,9521 | 2 | 72,733 | .000*** | 0,171 |

| restricted professionality | 4,8564 | |||||

| intermediate professionality | 5,2757 | |||||

| Openness to authority | extended professionality | 5,5626 | 2 | 61,263 | .000*** | 0,148 |

| restricted professionality | 4,0079 | |||||

| intermediate professionality | 4,6150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).