1. Introduction

Cranial cruciate ligament deficits progress to secondary osteoarthritis and are the most common orthopedic diseases that cause lameness and limping [

5,

6]. Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) was a surgical technique designed in 1993 to stabilize the stifle joint during weight-bearing without relocating ligaments and with neutralization of the cranial drawer sign [

20]. Similar to orthopedic surgery, intraoperative or postoperative complications involving soft tissues, bones, implants, or complex elements can occur in TPLO [

2]. After TPLO surgery, 6 months of rehabilitation compared to the group that did not experience rehabilitation showed a rapid recovery in reducing the progression of osteoarthritis, increasing mild or moderate activity, and improving maximum vertical force (MVF) [

1]. Infrared thermographic imaging is an evaluation method that does not cause invasive pain to the patient and can objectify the condition of the disease or abnormality by showing visual differences. When the body is inflamed, it is confirmed that the body temperature rises compared with the contralateral side [

4,

16] . When the weight load occurred on the affected limb of the patient with lameness, the MVF on the affected limb decreased compared with that on the unaffected limb. After TPLO, subtle lameness is not visually accurate and may interfere with patient recovery. Most importantly, because the initial rehabilitation can fail and become chronic, rehabilitative intervention through gait analysis is essential for recovery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient

A neutered 5.1 kg, 7-year-old Maltese dog who underwent TPLO surgery 42 days ago for a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament of the right hind limb presented for rehabilitation. After the surgery, the owner reported that the patient did not seem to support the weight well and seemed uncomfortable, had never undergone rehabilitation, and was asked by a veterinary surgeon to perform passive range of motion exercises and walk at home for a short time. There was no abnormality in the complete blood cell count at the time of surgery, and there was an increase in alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl peptidase and a decrease in creatinine in serum chemical analysis. Medical tests on the liver and biliary system were also conducted. On physical examination, there was second-grade medial patellar luxation on the left hindlimb, and the right hindlimb had no difficulty flexing the stifle joint but showed a whining pain reaction at the end of the extension. The patient participated in rehabilitation treatment six times a month, and no internal medicine was prescribed.

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Digital Thermal Image

The unaffected and affected sides in the front and medial views were simultaneously measured using a digital thermal imaging device (Digatherm®, IR-Pad 320, INFRARED CAMERAS INC., USA) with a spectral band between 7 and 14 µm a resolution of 336 × 256 pixels. The dog had limited exercise and was maintained in temperature-controlled runs and was measured at room temperature and moisture (20–24 °C, 40-45%) at 50-60 cm from the camera.

2.2.2. Gait Analysis

To establish a treadmill exercise plan, the evaluator asked the owner to leash the dog and walk as usual and measured MVF and symmetry index (SI) using a gait analysis device (FDM-TPROF CanidGait®, Zebris Medical GmbH, Germany).

2.2.3. Helsinki Chronic Pain Index

The Helsinki chronic pain index (HCPI) was used to assess chronic pain in dogs. It is used as an assessment tool for chronic pain at the beginning and end of rehabilitation.

2.2.4. Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation

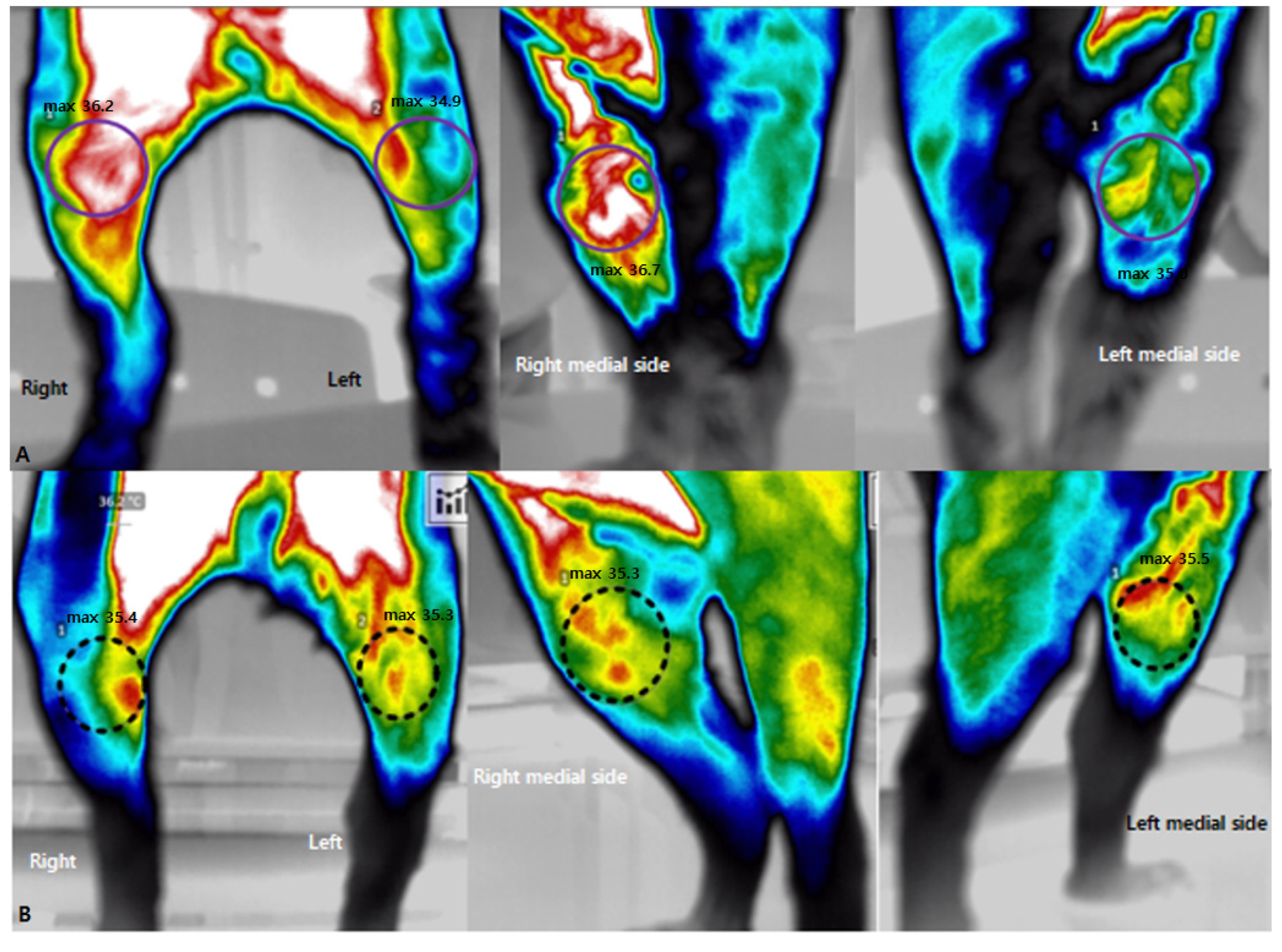

In the first evaluation using gait analysis, the difference in the bilateral hind limbs in MVF was 34%. On the digital thermal image device, the medial view of the stifle joint in the affected limb was 1.3 °C higher than the opposite side in the body temperature; thus, a cold pack was applied for 15 min before exercise (

Figure 1A). Exercise was then performed for 5 min at a speed of 1.5 km/h of comfortable walking on a treadmill and for 3 min at rest. A total of four sets were applied (

Figure 1B). After 5 min of rest, two electrodes were contacted medial and lateral on the stifle joint using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (PT3010-P, S+B medVET GmbH, Germany) to control pain and applied at 80–120 Hz and 25 us for 20 min with high frequency and low intensity (

Figure 1C). A cold pack was applied for 15 min to reduce the temperature around the stifle joint.

In the second gait analysis, the difference in the bilateral hind limbs in MVF was 26%; therefore, rehabilitation was applied as in the first treatment method. In the third gait analysis, it was confirmed that the difference in the MVF of the affected limb compared with the unaffected limb was slightly improved to 18%, and physical examination showed a decrease in pain reaction during full extension. A cold pack was applied for 20 min before the treadmill exercise, 5 min of treadmill exercise was applied at 2.0 km/h, and then 3 min break was performed in two sets. Five minutes of treadmill exercise was applied at 2.5 km/h, and 3 min break was performed in two sets. TENS was applied in the same manner for 20 min, and a cold pack was applied again for 15 min.

In the fourth gait analysis, compared with the unaffected hindlimb, it was confirmed that the difference gradually improved to 9%. Five minutes of treadmill exercise was applied at 2.0 km/h, and then a 3 min break was performed in three sets. Five minutes of treadmill exercise was applied at 2.5 km/h, and 3 min break was performed. The TENS and cold packs were applied in the same manner.

In the fifth evaluation using a gait analysis device, it was confirmed that the affected limb showed a 4% difference compared with the unaffected limb and improved by 30% compared with that before treatment. In the same manner, a cold pack was applied before the treadmill exercise, and the treadmill exercise started at 2.5 km/hr and increased by 0.5 km/hr over three times to 4.0 km/hr, which was also applied for 5 min and rested for 3 min. There was no longer any pain response in the range of the stifle joint. Therefore, TENS was not applied, and only a cold pack was used.

In the sixth evaluation using the gait analysis device, it was confirmed that MVF in the affected limb increased by 6% compared with the unaffected hind limb. The treadmill exercise proceeded with the same protocol as the fifth exercise, and the cold pack was applied in the same manner. Rehabilitation was completed, and the owner was notified that it was the last treatment.

3. Results

3.1. Digital Thermal Imaging

Digital thermal imaging devices have not only the advantage of providing quantitative image information of thermal alteration but also non-invasiveness, high versatility, and the absence of contamination. It has been used for tumor diagnosis and orthopedic and neurological disease evaluation [

21]. It was possible to evaluate changes in tissue perfusion for a specific area identified on a computer. The medial and lateral sides around the stifle joint were set as the regions of interest, and the affected and unaffected sides were compared. Before physiotherapy and rehabilitation, the patient’s body temperature around the stifle joint was measured using a digital thermal imaging device. As a result of the measurement from the front, the maximum point on the medial view of the right stifle was 36.2 °C, and the maximum point of the left stifle was 34.9 °C. The medial side was also measured for a more detailed evaluation. A maximum temperature of 36.7 °C was measured on the medial side of the stifle joint of the right hindlimb, and a maximum temperature of 35 °C was measured on the medial side of the left stifle joint (

Figure 2A). After the sixth physical therapy and treadmill exercises, the body temperature around the stifle joint in the front was measured at a maximum temperature of 35.4 °C on the right and 35.3 °C on the left. On the medial side, a maximum temperature of 35.3 °C on the right and 35.5 °C on the left were measured. No significant thermal differences were observed (

Figure 2B).

3.2. Gait Analysis

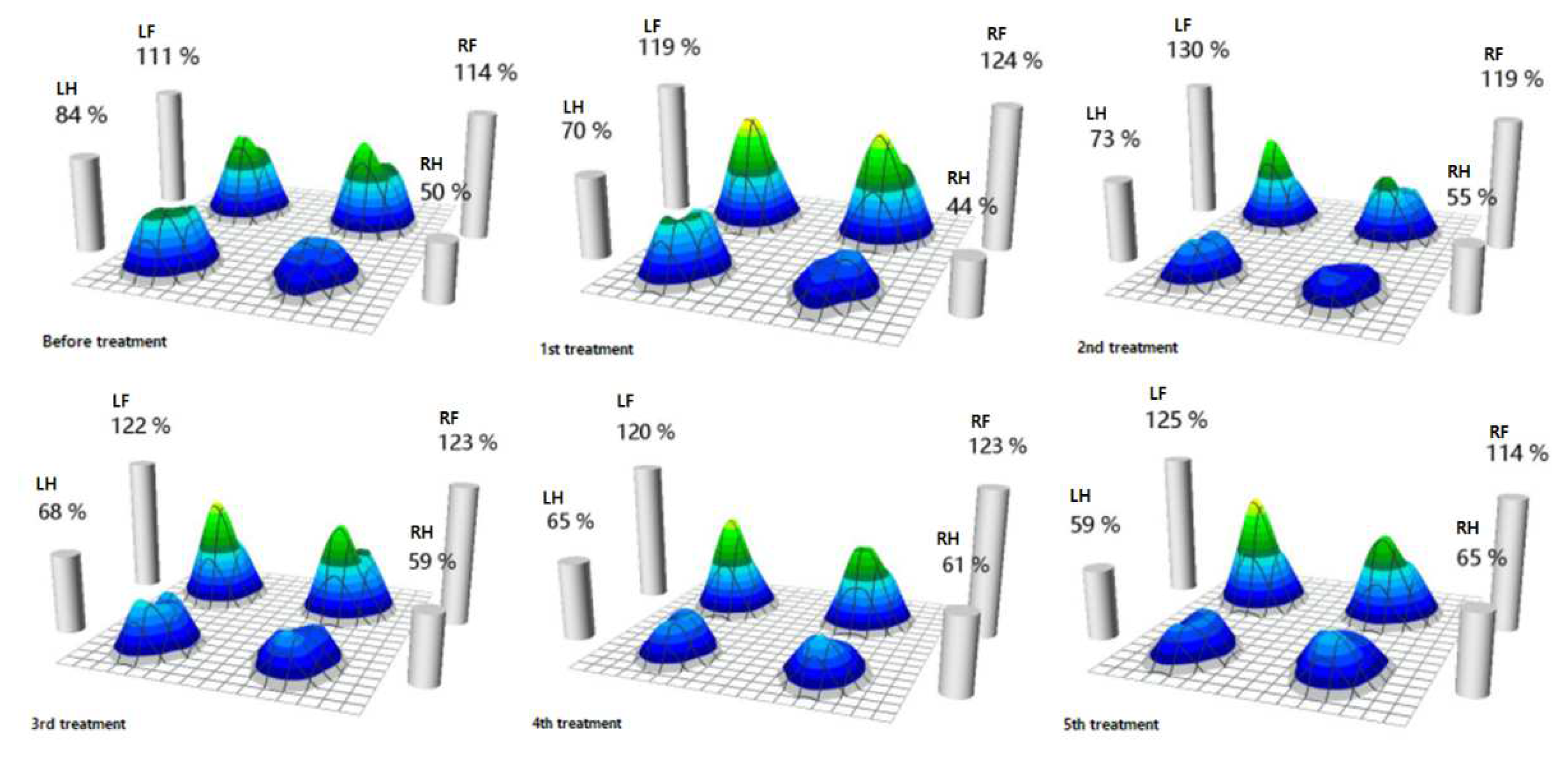

Before physiotherapy and rehabilitation, the patient's affected hind limb had a 34% decrease in MVF compared with the unaffected hind limb. As physical therapy and treadmill exercise were repeated, MVF in both hind limbs improved in balance, so the difference in MVF on the affected and unaffected hind limbs was only 6% in the fourth treatment. The MVF increased further in the right hind limb after the fifth treatment (

Figure 3).

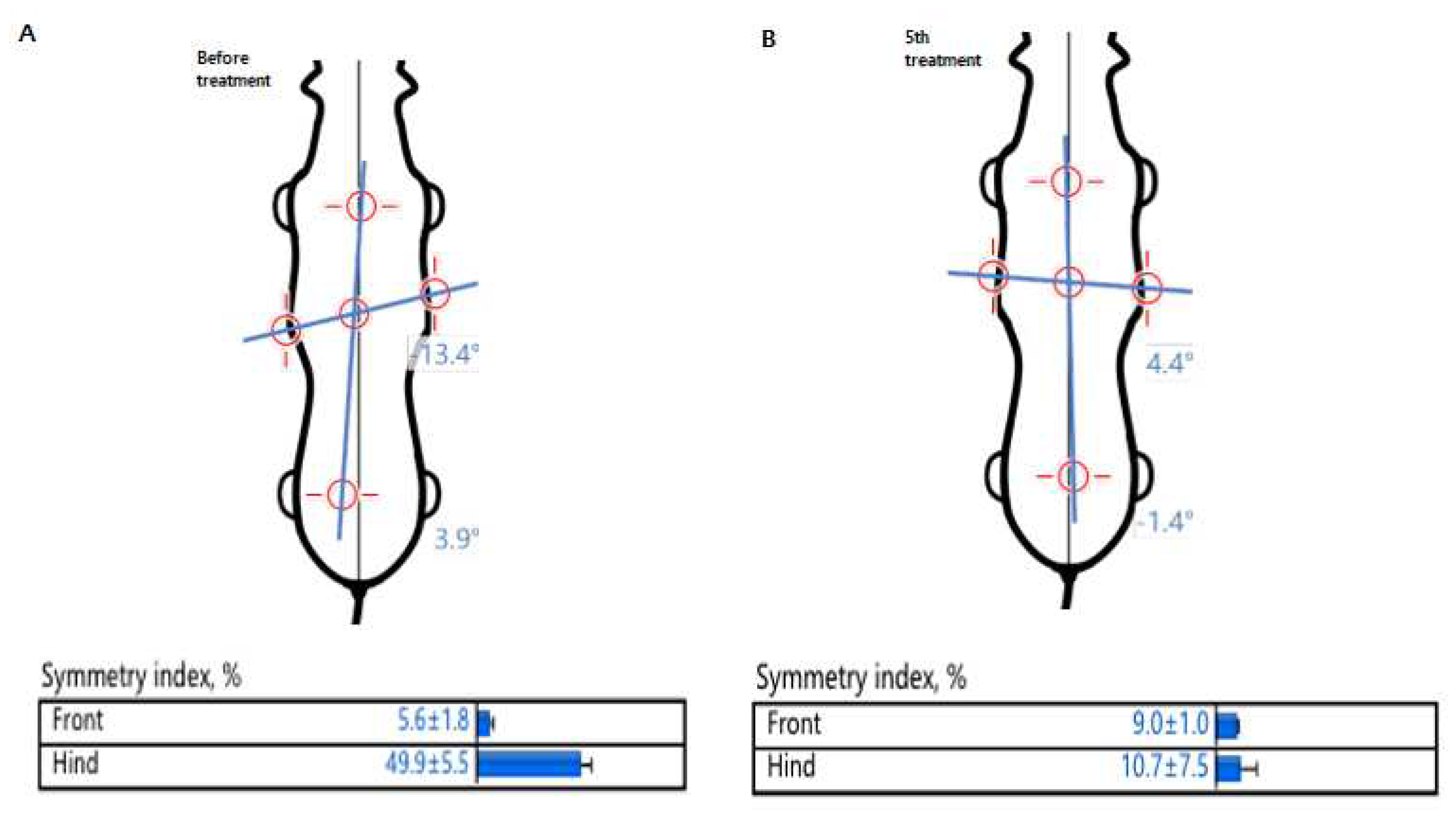

In addition, comparing pre-and post-physiotherapy and rehabilitation in terms of body symmetry, the longitudinal tilt was significantly reduced, moving the axis to the center of the body. The SI also decreased after rehabilitation, confirming that the patient improved to a symmetric gait (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Loss of function of the cranial cruciate ligament progresses in the order of gradual stretch, partial rupture, and complete rupture and is the most common orthopedic problem in the hindlimbs of adult dogs [

5,

14]. The cruciate ligament serves as a primary stabilizer for the stifle joint to limit excessive forward displacement of the tibia to the femur by preventing internal rotation and hyperextension of the stifle joint [

6,

18].

In horses, the variables of body temperature change were caused by tissue vascularization and metabolism and showed symmetry; dogs had similar patterns. These results suggest that, when evaluating patients with unilateral diseases, the region of interest can be used as a control image for comparative purposes [

8,

17]. Based on previous research results, this study attempted to confirm the presence or absence of abnormalities by using digital thermography imaging of the front and medial sides around the stifle joints of a dog with lameness after TPLO. As a result of measuring body temperature on the left and right sides in horses with asymmetrical swelling and lameness in the right hindlimb’s tarsal and metatarsal joints, the temperature difference of 1.3 °C and 1.6 °C, respectively, compared with the contralateral side was measured, and cartilage damage was confirmed through an autopsy [

16]. In humans with patellofemoral arthralgia, the anterior knee view shows an increase in body temperature on the medial side of the patella, whereas the medial knee view shows that this body temperature rise radiates from the patellar insertion of the vastus medialis into the muscle itself [

3]. In this case, it was confirmed that the body temperature of the affected hindlimb with lameness was increased by 1.7 °C compared with the unaffected hindlimb, especially on the medial side. In TPLO surgery, it is considered to result from a temperature rise radiating to the surrounding tissues due to noninfectious inflammatory reactions caused by incomplete recovery of soft tissue and connective tissue through inner access. After the fifth rehabilitation, the maximum temperature was 35.4 °C on the right stifle joint and 35.3 °C on the left stifle joint in the front view, and the right and left stifle joint was measured at 35.3 °C and 35.5 °C, respectively, on the medial view. We confirmed that there is a slight difference.

After the extracapsular technique, edema was most frequently reduced in the group where only cold compression was applied to reduce stifle joint edema [

19]. Cold treatment is effective in reducing pain, edema, collagenolysis, synovial cystitis, and joint damage caused by chronic arthritis diseases, enough to reduce the use of painkillers [

10]. Cooling the tissue lowers the response and metabolic rates of acute inflammation, minimizes histamine secretion, reduces tissue damage, and decreases the rate of firing of muscle spindles and spasms [

9,

15]. In this case, the increased body temperature identified on the affected hind limb through the digital thermal imaging device was regarded as inflammation of the tissue around the joint after TPLO, and the inflammation was alleviated by applying a cold pack, which helped reduce tissue damage.

Gait analysis can be used to evaluate the stabilization of the stifle joint before and after TPLO and is a useful method for objective and repetitive measurement of the limb [

10]. The SI for MVF in the affected limbs of dogs subjected to intensive physical therapy, including diet for weight loss and TENS, was significantly improved over a period of 60–180 days of application [

11]. In a dog with delayed rehabilitation for 6 months due to degenerative arthritis and sciatic nerve injury, symmetry improved after the seventeenth rehabilitation session [

7]. In this case, cold packs and TENS were used for physical therapy, and the MVF and SI were confirmed using a gait analysis device. Compared with before treatment, it was confirmed that MVF in the affected hindlimb was improved, and SI was also improved symmetrically as the difference in MVF on the unaffected and affected hindlimb decreased, and the result was symmetrically improved. However, the increase in MVF in the affected hind limb of the patient in the sixth gait analysis needs to be confirmed by repeated analyses. In addition, because the unaffected hind limb had second-grade medial patellar luxation, it can be considered that the MVF on the affected side was improved over that on the unaffected side. There was no significant difference between the physical therapy and home exercise groups 6 weeks after surgery in terms of the willingness to bear weight on the affected hind limb and the willingness to lift the contralateral hind limb [

13]. However, in this case, continuous lameness was observed for 6 weeks after surgery using a gait analysis device. The patient gradually resolved lameness through physical therapy and treadmill exercise.

5. Conclusions

31.1% of dogs who scored more than 12 points in 253 HCPI questionnaires after cranial cruciate ligament surgery continuously were indicated for chronic pain with lameness [

12]. In this case, pain was also identified in the range of motion, and the patient was evaluated as having serious pain by scoring 24 points on the HCPI before physiotherapy and rehabilitation. After physiotherapy and rehabilitation, the HCPI score was 2, confirming that the patient was free from pain. Rehabilitation is often neglected in the clinical veterinary practice. Rehabilitative intervention and evaluation are essential to closely observe the pain and lameness that may occur after cranial cruciate ligament surgery and to quickly return to activities of daily living without becoming chronic.

Author Contributions

S.H.L., J-H.C., C-H.K and D.L. contributed to the data collection and execution. S.H.L., J-H.C., C-H.K and D.L. contributed to the data interpretation. S.H.L and D.L. contributed to the study design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baltzer, W.I.; Smith-Ostrin, S.; Warnock, J.J.; Ruaux, C.G. Evaluation of the clinical effects of diet and physical rehabilitation in dogs following tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018, 252, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, M.S.; Peirone, B. ; Complications of tibial plateau levelling osteotomy in dogs. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2012, 25, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devereaux, M.D.; Lachmann, S.M. Patello-femoral arthralgia in athletes attending a sports injury clinic. Br J Sports Med. 1984, 18, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, L.C.; Gaughan, E.M.; Gorondy, D.A.; Hogge, S. Spire, M.F. The effect of perineural anesthesia on infrared thermographic images of the forelimb digits of normal horses. Can. Vet. J. 2003, 44, 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.A.; Austin, C.; Breur, G.J. Incidence of canine appendicular musculoskeletal disorders in 16 veterinary teaching hospitals from 1980 through 1989. Veterinar y and Comparative Or thopaedics and Traumatology. 1994, 7, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Johnson, A.L. Cranial cruciate ligament rupture. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and postoperative rehabilitation. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1993, 23, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. The Effect of Animal Physiotherapy on Balance and Walking in Dog with Sciatic Nerve Injury and Degenerative Joint Disease, Case Report. Phys Ther Rehabil Sci. 2022, 11, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughin, C.A.; Marino, D.J. Evaluation of thermographic imaging of the limbs of healthy dogs. Am. J Vet Res. 2007, 68, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaster, W. A. literary review on ice therapy in injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1977, 5, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millis, D.L.; Levine, D. Canine Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2014. 2nd Edition. p222-224, 316.

- Mlacnik, E et al: Effects of caloric restriction and a moderate or intense physiotherapy program for treatment of lameness in overweight dogs with osteoarthritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006, 229, 1756–1760. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mölsä, S.H.; Hyytiäinen, H.K.; Hielm-Björkman, A.K.; Laitinen-Vapaavuori, O.M. Use of an owner questionnaire to evaluate long-term surgical outcome and chronic pain after cranial cruciate ligament repair in dogs: 253 cases (2004–2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013, 243, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, M.L.; Preston, C.A.; McGowan, C.M. Effects of early intensive postoperative physiotherapy on limb function after tibial plateau leveling osteotomy in dogs with deficiency of the cranial cruciate ligament. Am J Vet Res. 2006, 67, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ness, M.; Abercromby, R.; May, C.; Turner, B.; Carmichael, S. A survey of orthopaedic conditions in small animal veterinar y practice in Britain. Veterinar y and Comparative Or thopaedics and Traumatology. 1996, 9, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J.; Stravino, V. A review of cryotherapy. Phys Ther. 1972, 52, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H. J et al. Use of thermography in lameness caused by musculoskeletal disease in Thoroughbred mare. Korean J Vet Serv. 2012, 35, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, R.C.; McCoy, M.D. Thermography in the diagnosis of inflammatory processes in the horse. Am J Vet Res. 1980, 41, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reif, U.; Hulse, D.A.; Hauptman, J.G. Effect of tibial plateau leveling on the stability of the canine cranial cruciatedeficient stifle joint: an in vitro study. Vet Surg 2002, 31, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rexing, J.; Dunning, D.; Siegel, A. R et al. Effects of cold compression, bandaging, and microcurrent electrical therapy after cranial cruciate ligament repair in dogs. Vet Surg. 2010, 39, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slocum, B.; Slocum, T.D. Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy for repair of cranial cruciate ligament rupture in the canine. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1993, 23, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, S.; Bruno, E.; Nanni, C.; Musella, V.; Antonucci, M.; Spinella, G. Superficial heating evaluation by thermographic imaging before and after tecar therapy in six dogs submitted to a rehabilitation protocol: A pilot study. Animals. 2021, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).