Submitted:

08 August 2023

Posted:

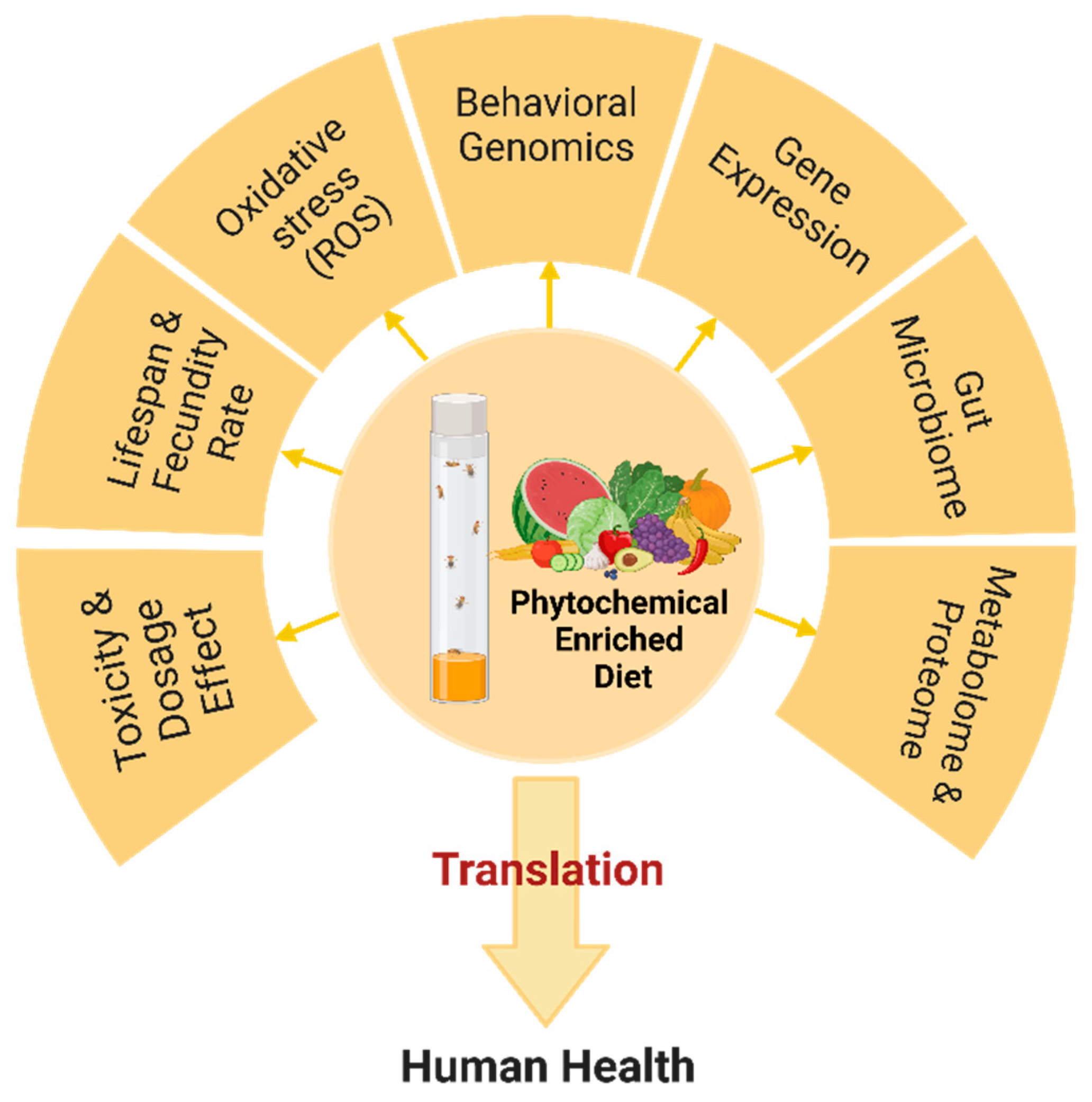

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Phytochemicals and Their Potential Therapeutic Benefits

3. Advantages of Using Drosophila as a Translational Model for Testing Phytochemicals

4. Methods for Testing the Efficacy of Phytochemicals in Drosophila

5. Studies Evaluating the Effect of Phytochemicals by Using Drosophila

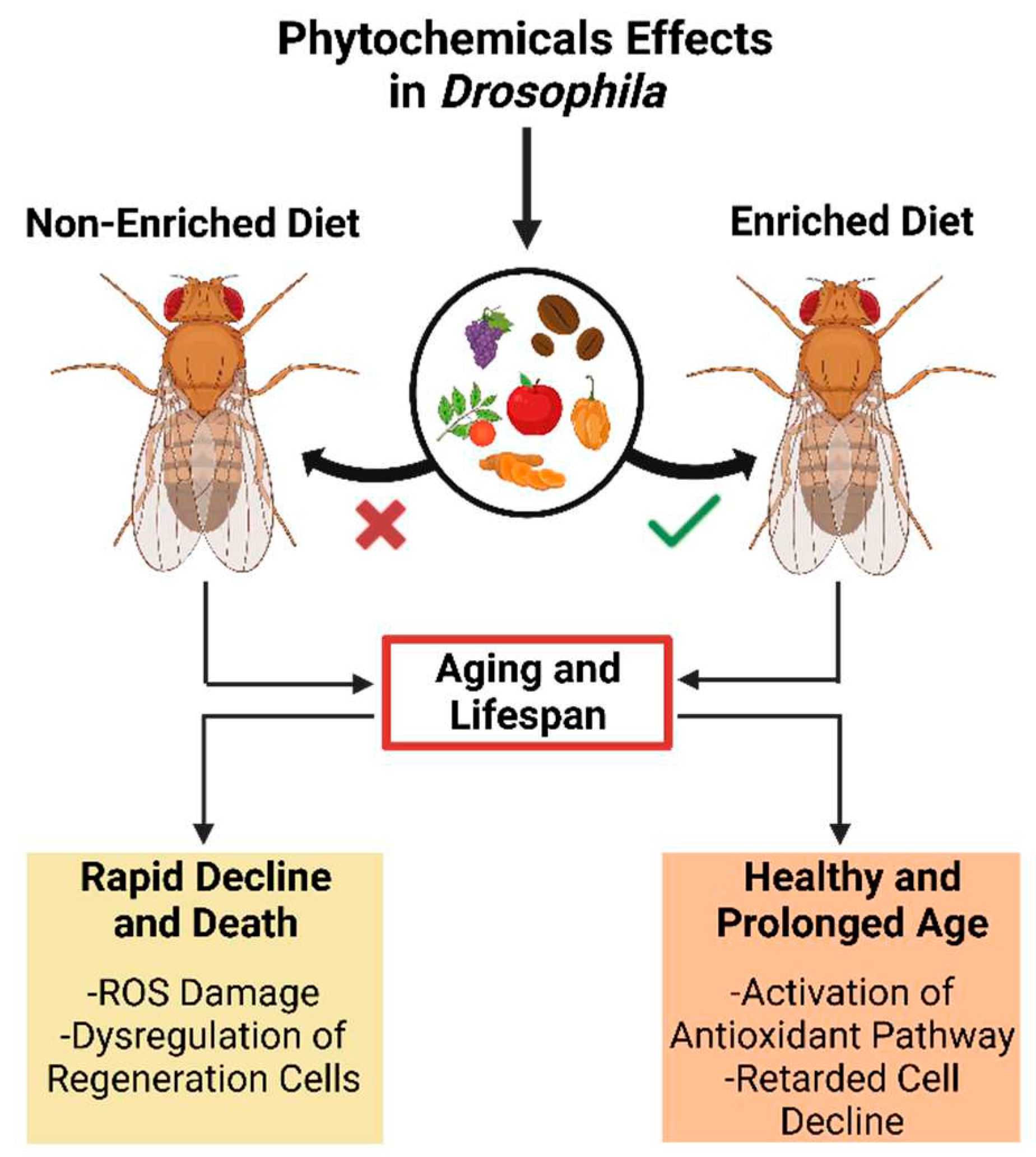

5.1. Phytochemical Effect on Aging

5.2. Development and Lifespan

5.3. Metabolism

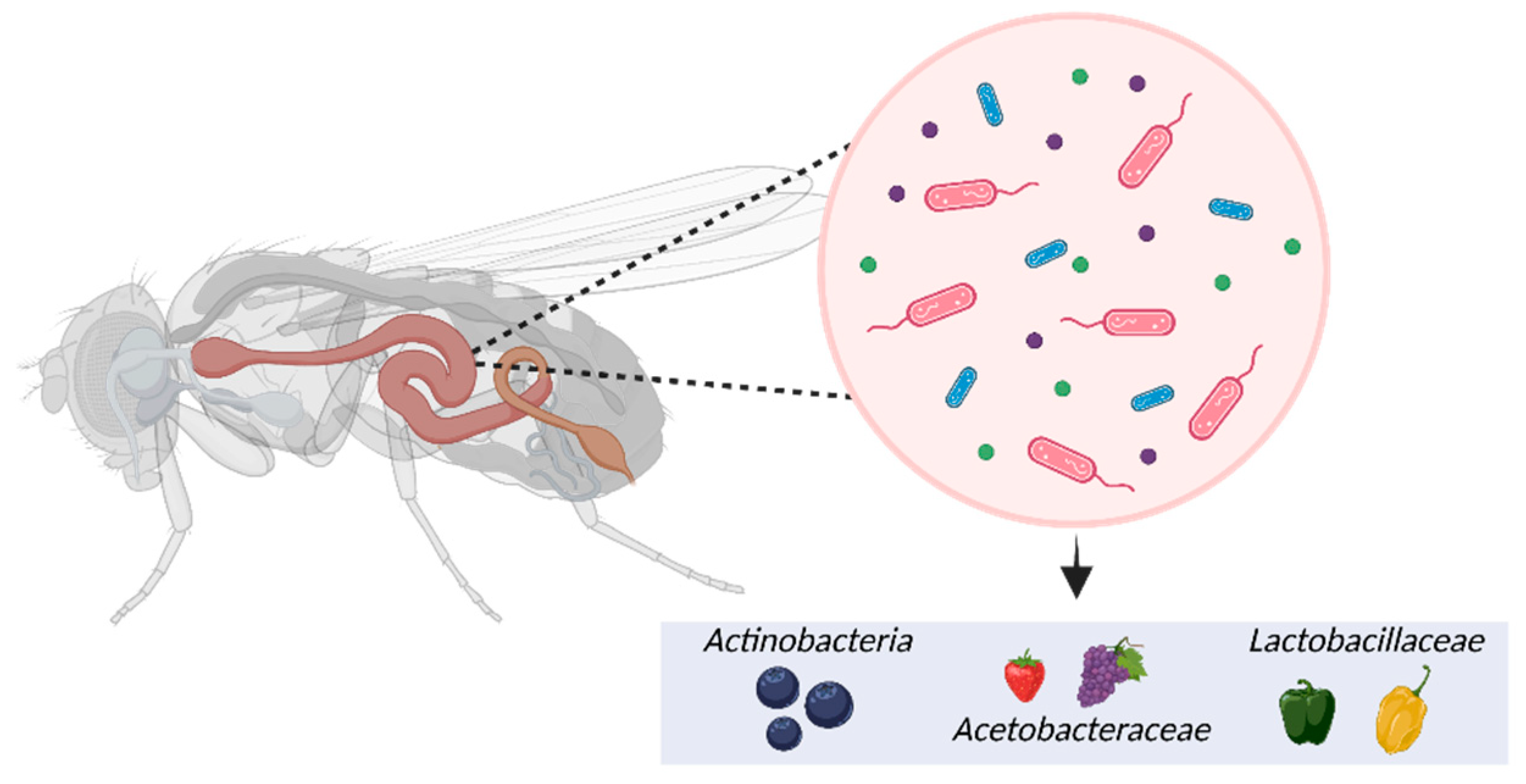

5.4. Microbiome

5.5. Neurodegenerative Diseases

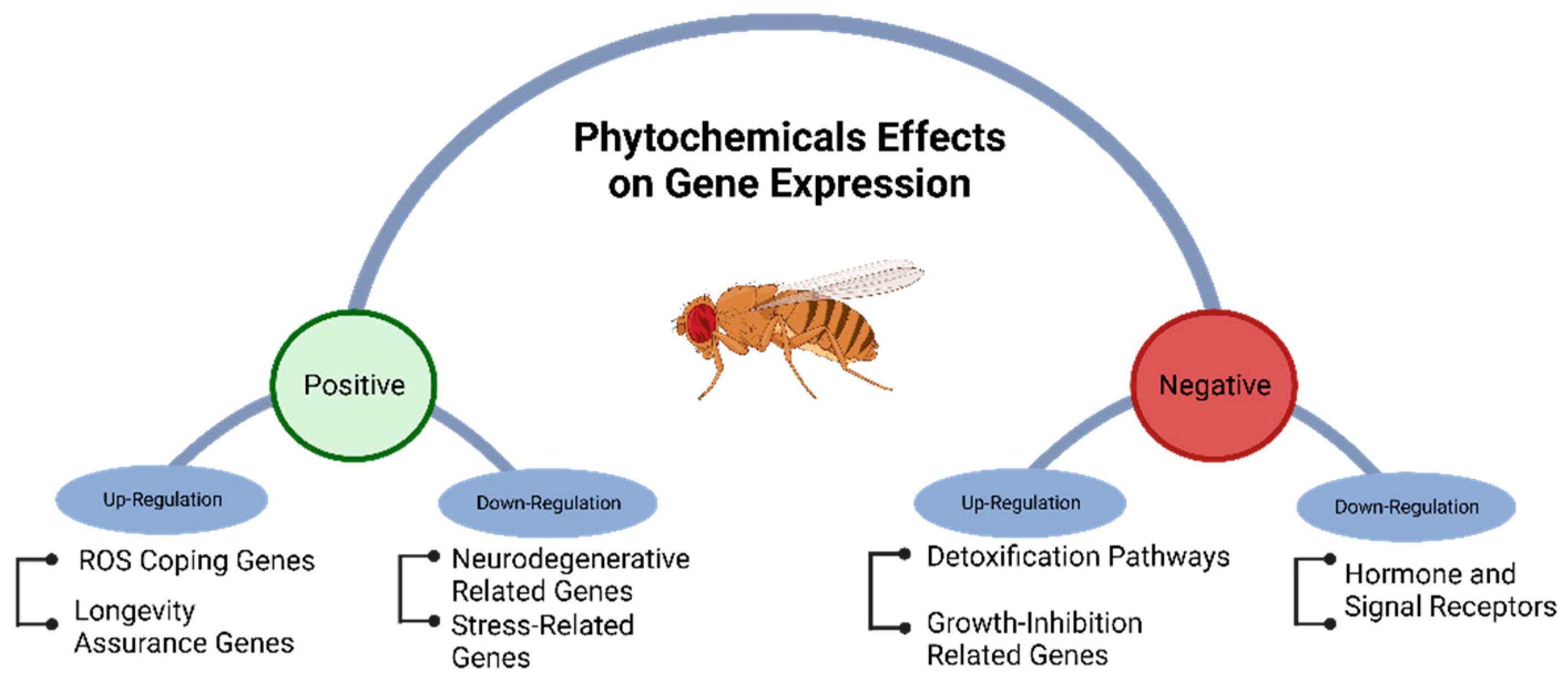

6. Gene Regulation Induced by Phytochemicals in Drosophila

7. Challenges and Limitations of Using Drosophila as a Translational Model

8. Future Directions and Opportunities for Using Drosophila to Test Phytochemicals

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oladipo, A.; et al. Production and functionalities of specialized metabolites from different organic sources. Metabolites 2022, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; et al. Major Phytochemicals: Recent Advances in Health Benefits and Extraction Method. Molecules 2023, 28, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.; et al. Phytochemicals as candidate therapeutics: An overview. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research 2010, 3, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, A.P. and B.H. Arjmandi, Health benefits of plant-based nutrition: focus on beans in cardiometabolic diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; et al. Antioxidant phytochemicals for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Molecules 2015, 20, 21138–21156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; et al. Antidiabetic phytochemicals from medicinal plants: prospective candidates for new drug discovery and development. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.-C.; et al. Effects of phytochemicals on cellular signaling: reviewing their recent usage approaches. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2020, 60, 3522–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-I.; et al. Drosophila as a model system for studying lifespan and neuroprotective activities of plant-derived compounds. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 2011, 14, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; et al. Comprehensive review on nutraceutical significance of phytochemicals as functional food ingredients for human health management. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2019, 8, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; et al. Evaluation of Safety and Efficacy of Nutraceuticals Using Drosophila as an in vivo Tool. Nutraceuticals in Veterinary Medicine 2019, 685–692. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, K.C. and J. Montagne, Drosophila melanogaster: A powerful tiny animal model for the study of metabolic hepatic diseases. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12.

- Pratomo, A.R.; et al. Drosophila as an Animal Model for Testing Plant-Based Immunomodulators. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.L. Olfactory memory formation in Drosophila: from molecular to systems neuroscience. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 28, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montell, C. Drosophila sensory receptors—a set of molecular Swiss Army Knives. Genetics 2021, 217, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapatna, V.A., R.L. Cagan, and T.K. Das, Drosophila cancer models. Developmental Dynamics 2012, 241, 107–118.

- Yadav, A.K., S. Srikrishna, and S.C. Gupta, Cancer drug development using drosophila as an in vivo tool: from bedside to bench and back. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2016, 37, 789–806. [CrossRef]

- Himalian, R., S.K. Singh, and M.P. Singh, Ameliorative role of nutraceuticals on neurodegenerative diseases using the Drosophila melanogaster as a discovery model to define bioefficacy. Journal of the American Nutrition Association 2022, 41, 511–539. [CrossRef]

- Luthra, R. and A. Roy, Role of medicinal plants against neurodegenerative diseases. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 2022, 23, 123–139. [CrossRef]

- Samtiya, M.; et al. Potential health benefits of plant food-derived bioactive components: An overview. Foods 2021, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; et al. Oxidative stress: an essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiological reviews 2014, 94, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.N. Bioactive phytochemicals in Indian foods and their potential in health promotion and disease prevention. Asia Pacific Journal of clinical nutrition 2003, 12. [Google Scholar]

- AlAli, M.; et al. Nutraceuticals: Transformation of conventional foods into health promoters/disease preventers and safety considerations. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, M.; et al. Phytochemistry of medicinal plants. Journal of pharmacognosy and phytochemistry 2013, 1, 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga, C.G.; et al. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food & function 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, A.; et al. Health benefits of polyphenols: A concise review. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2022, 46, e14264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, M., C. Riva, and A. Vinet, Effects of dietary polyphenols on metabolic syndrome features in humans: a systematic review. Obesity reviews 2016, 17, 573–586. [CrossRef]

- Gombart, A.F., A. Pierre, and S. Maggini, A review of micronutrients and the immune system–working in harmony to reduce the risk of infection. Nutrients 2020, 12, 236. [CrossRef]

- Basith, S.; et al. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of capsaicin and its analogues in pain and other diseases. Molecules 2016, 21, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; et al. Biological properties, bioactive constituents, and pharmacokinetics of some Capsicum spp. and capsaicinoids. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; et al. Capsaicin—the major bioactive ingredient of chili peppers: Bio-efficacy and delivery systems. Food & function 2020, 11, 2848–2860. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ortiz, C.; et al. Peppers in Diet: Genome-Wide Transcriptome and Metabolome Changes in Drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoncini-Silva, C.; et al. Bioactive dietary components—Anti-obesity effects related to energy metabolism and inflammation. BioFactors 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, H.S.; et al. The benefits and risks of certain dietary carotenoids that exhibit both anti-and pro-oxidative mechanisms—A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, V.; et al. From carotenoid intake to carotenoid blood and tissue concentrations–implications for dietary intake recommendations. Nutrition Reviews 2021, 79, 544–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S. and T. Ramachandra, Phytochemical and pharmacological importance of turmeric (Curcuma longa): A review. Research & Reviews: A Journal of Pharmacology 2019, 9, 16–23.

- Micek, A.; et al. Dietary flavonoids and cardiovascular disease: a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis. Molecular nutrition & food research 2021, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Metsämuuronen, S. and H. Sirén, Bioactive phenolic compounds, metabolism and properties: A review on valuable chemical compounds in Scots pine and Norway spruce. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 18, 623–664. [CrossRef]

- Pizarroso, N.A.; et al. A review on the role of food-derived bioactive molecules and the microbiota–gut–brain axis in satiety regulation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolwinski, N.S., Introduction: Drosophila—A model system for developmental biology. 2017, MDPI. 9.

- Pandey, U.B. and C.D. Nichols, Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacological reviews 2011, 63, 411–436. [CrossRef]

- Jeibmann, A. and W. Paulus, Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism of brain diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 2009, 10, 407–440. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fuentes, C.; et al. A natural solution for obesity: Bioactives for the prevention and treatment of weight gain. A review. Nutritional neuroscience 2015, 18, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, R.S. Genetic analysis of insulin signaling in Drosophila. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2002, 13, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah, E. and N. Perrimon, Modeling metabolic homeostasis and nutrient sensing in Drosophila: implications for aging and metabolic diseases. Disease models & mechanisms 2014, 7, 343–350.

- Chatterjee, N. and N. Perrimon, What fuels the fly: Energy metabolism in Drosophila and its application to the study of obesity and diabetes. Science Advances 2021, 7.

- Catalkaya, G.; et al. Interaction of dietary polyphenols and gut microbiota: Microbial metabolism of polyphenols, influence on the gut microbiota, and implications on host health. Food Frontiers 2020, 1, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N. and A.E. Wagner, Drosophila melanogaster as an alternative model organism in nutrigenomics. Genes & nutrition 2019, 14, 1–11.

- Maitra, U., C. Stephen, and L.M. Ciesla, Drug discovery from natural products–Old problems and novel solutions for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2022, 210.

- Deshpande, P., N. Gogia, and A. Singh, Exploring the efficacy of natural products in alleviating Alzheimer’s disease. Neural regeneration research 2019, 14.

- Lee, S.-H. and K.-J. Min, Drosophila melanogaster as a model system in the study of pharmacological interventions in aging. Translational Medicine of Aging 2019, 3, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Lucanic, M., G.J. Lithgow, and S. Alavez, Pharmacological lifespan extension of invertebrates. Ageing research reviews 2013, 12, 445–458. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. Dietary polyphenols: regulate the advanced glycation end products-RAGE axis and the microbiota-gut-brain axis to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J.; et al. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature 2019, 571, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, T. and M. Tatar, Age-specific mortality and reproduction respond to adult dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of insect physiology 2001, 47, 1467–1473. [CrossRef]

- Rand, M.D. Drosophotoxicology: the growing potential for Drosophila in neurotoxicology. Neurotoxicology and teratology 2010, 32, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, I. and S.K. Abraham, Ameliorative effects of gallic acid, quercetin and limonene on urethane-induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicology mechanisms and methods 2017, 27, 286–292. [CrossRef]

- Tello, J.A.; et al. Animal models of neurodegenerative disease: Recent advances in fly highlight innovative approaches to drug discovery. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.E.; et al. An integrative omics perspective for the analysis of chemical signals in ecological interactions. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47, 1574–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diegelmann, S.; et al. The CApillary FEeder assay measures food intake in Drosophila melanogaster. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2017, e55024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; et al. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, C.; et al. Beneficial role of phytochemicals on oxidative stress and age-related diseases. BioMed research international 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rani, N.Z., K. Husain, and E. Kumolosasi, Moringa genus: a review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 108. [CrossRef]

- Iorjiim, W.M.; et al. Moringa oleifera leaf extract promotes antioxidant, survival, fecundity, and locomotor activities in Drosophila melanogaster. European Journal of Medicinal Plants 2020, 31, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagun-Ogunleye, O., A. Adedeji, and M. Vicente-Crespo, Moringa oleifera ameliorates age-related memory decline and increases endogenous antioxidant response in Drosophila melanogaster exposed to stress. African Journal of Biomedical Research 2020, 23, 397–406.

- Singh, A.; et al. Withanolides: Phytoconstituents with significant pharmacological activities. International Journal of Green Pharmacy (IJGP) 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabey, K.; et al. Withania somnifera and Centella asiatica Extracts Ameliorate Behavioral Deficits in an In Vivo Drosophila melanogaster Model of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holvoet, H.; et al. Withania somnifera Extracts Promote Resilience against Age-Related and Stress-Induced Behavioral Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster; a Possible Role of Other Compounds besides Withanolides. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, S. Obesity: causes and consequences. Women's health medicine 2004, 1, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C., R. Wang, and C.-C. Wei, Anti-aging effects of dietary phytochemicals: From Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, rodents to clinical studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 1–26.

- Sheng, X.; et al. Antioxidant effects of caffeic acid lead to protection of drosophila intestinal stem cell aging. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; et al. Green tea catechins and broccoli reduce fat-induced mortality in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2008, 19, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.E.; et al. Epigallocatechin gallate affects glucose metabolism and increases fitness and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Oncotarget 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; et al. Impacts of turmeric and its principal bioactive curcumin on human health: Pharmaceutical, medicinal, and food applications: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suckow, B.K. and M.A. Suckow, Lifespan extension by the antioxidant curcumin in Drosophila melanogaster. International journal of biomedical science: IJBS 2006, 2, 402.

- Lee, K.-S.; et al. Curcumin extends life span, improves health span, and modulates the expression of age-associated aging genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Rejuvenation research 2010, 13, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiley, T.A.; et al. Life span extension in Drosophila melanogaster induced by morphine. Biogerontology 2011, 12, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buescher, J.L.; et al. Evidence for transgenerational metabolic programming in Drosophila. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2013, 6, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Colombani, J. and D.S. Andersen, The Drosophila gut: a gatekeeper and coordinator of organism fitness and physiology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology 2020, 9, e378. [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.D. and C.S. Thummel, Diabetic larvae and obese flies—emerging studies of metabolism in Drosophila. Cell metabolism 2007, 6, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, A. and D.Y.R. Stainier, Lessons from “lower” organisms: what worms, flies, and zebrafish can teach us about human energy metabolism. PLoS genetics 2007, 3, e199.

- Singla, P., A. Bardoloi, and A.A. Parkash, Metabolic effects of obesity: a review. World journal of diabetes 2010, 1, 76. [CrossRef]

- Heinrichsen, E.T.; et al. Metabolic and transcriptional response to a high-fat diet in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular metabolism 2014, 3, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S. Obesity in midlife: lifestyle and dietary strategies. Climacteric 2020, 23, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, Y. and V. Benítez, Phytochemicals: Dietary sources, innovative extraction, and health benefits. Foods 2021, 11, 72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; et al. Dietary capsaicin and its anti-obesity potency: from mechanism to clinical implications. Bioscience reports 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa-Rivera, M.G. and N. Ochoa-Alejo, Chili pepper carotenoids: Nutraceutical properties and mechanisms of action. Molecules 2020, 25.

- Chung, J.H., V. Manganiello, and J.R. Dyck, Resveratrol as a calorie restriction mimetic: therapeutic implications. Trends in cell biology 2012, 22, 546–554. [CrossRef]

- Bayliak, M.M.; et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate attenuates toxic effects of sodium nitroprusside and hydrogen peroxide in Drosophila melanogaster. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2015, 40, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adefegha, S.A., O.B. Ogunsuyi, and G. Oboh, Purple onion in combination with garlic exerts better ameliorative effects on selected biomarkers in high-sucrose diet-fed fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). Comparative Clinical Pathology 2020, 29, 713–720. [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; et al. Metabolic activity of radish sprouts derived isothiocyanates in drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.U.; et al. Herbal medicines for diabetes mellitus: a review. Int J PharmTech Res 2010, 2, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Ugbedeojo, S.P.; et al. The phytochemical constituents, hypoglycemic, and antioxidant activities of Senna occidentalis (L.) ethanolic leaf extract in high sucrose diet fed drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology 2021, 24, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Saliu, J.A., A.M. Olajuyin, and A. Akinnubi, Modulatory effect of Artocarpus camansi on ILP-2, InR, and Imp-L2 genes of sucrose–induced diabetes mellitus in Drosophila melanogaster. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2021, 246.

- De Filippis, F.; et al. Specific gut microbiome signatures and the associated pro-inflamatory functions are linked to pediatric allergy and acquisition of immune tolerance. Nature Communications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; et al. Biogenic phytochemicals modulating obesity: From molecular mechanism to preventive and therapeutic approaches. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamanu, E. and S.N. Rai, The link between obesity, microbiota dysbiosis, and neurodegenerative pathogenesis. Diseases 2021, 9, 45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, A.E. The Drosophila model for microbiome research. Lab animal 2018, 47, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehrke, L.; et al. The impact of genome variation and diet on the metabolic phenotype and microbiome composition of Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.C.-N., A.J. Dobson, and A.E. Douglas, Gut microbiota dictates the metabolic response of Drosophila to diet. Journal of Experimental Biology 2014, 217, 1894–1901.

- Xu, Z. and R. Knight, Dietary effects on human gut microbiome diversity. British Journal of Nutrition 2015, 113, S1–S5.

- Garcia-Lozano, M.; et al. Effect of pepper-containing diets on the diversity and composition of gut microbiome of drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekhnovich, E.I.; et al. The effects of Levilactobacillus brevis on the physiological parameters and gut microbiota composition of rats subjected to desynchronosis. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Padilla, Y.; et al. Persistence of diet effects on the microbiota of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). The Canadian Entomologist 2020, 152, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.D. and A.E. Douglas, Interspecies interactions determine the impact of the gut microbiota on nutrient allocation in Drosophila melanogaster. Applied and environmental microbiology 2014, 80, 788–796. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binda, C.; et al. Actinobacteria: a relevant minority for the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Digestive and Liver Disease 2018, 50, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayarathne, S.; et al. Protective effects of anthocyanins in obesity-associated inflammation and changes in gut microbiome. Molecular nutrition & food research 2019, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, S., N. Lomis, and S. Prakash, A novel polyphenolic prebiotic and probiotic formulation have synergistic effects on the gut microbiota influencing Drosophila melanogaster physiology. Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology 2018, 46, 441–455. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; et al. Use of dietary phytochemicals to target inflammation, fibrosis, proliferation, and angiogenesis in uterine tissues: promising options for prevention and treatment of uterine fibroids? Molecular nutrition & food research 2014, 58, 1667–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Hernández, D.; et al. Black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) polyphenolic extract exerts antioxidant and antiaging potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; et al. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside represses tumor growth and invasion in vivo by suppressing autophagy via inhibition of the JNK signaling pathways. Food & function 2021, 12, 387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.S.; et al. Amyloid β-protein oligomers promote the uptake of tau fibril seeds potentiating intracellular tau aggregation. Alzheimer's research & therapy 2019, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, A.; et al. Potential of Pueraria tuberosa (Willd.) DC. to rescue cognitive decline associated with BACE1 protein of Alzheimer's disease on Drosophila model: An integrated molecular modeling and in vivo approach. International journal of biological macromolecules 2021, 179, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.; et al. Understanding Pathophysiology of Sporadic Parkinson's Disease in Drosophila Model: Potential Opportunities and Notable Limitations. 2016, IntechOpen.

- Maitra, U.; et al. GardeninA confers neuroprotection against environmental toxin in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Communications Biology 2021, 4, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Y.H.; et al. Lemongrass Extract Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Delayed the Loss of Climbing Ability in Transgenic Drosophila Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Letters in Drug Design & Discovery 2021, 18, 987–997. [Google Scholar]

- Ssempijja, F.; et al. Attenuation of Seizures, Cognitive Deficits, and Brain Histopathology by Phytochemicals of Imperata cylindrica (L.) Beauv (Poaceae) in Acute and Chronic Mutant Drosophila melanogaster Epilepsy Models. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing-Simmons, E.; et al. Independence of chromatin conformation and gene regulation during Drosophila dorsoventral patterning. Nature genetics 2021, 53, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, J.; et al. REDfly: the transcriptional regulatory element database for Drosophila. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, D828–D834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fear, J.M.; et al. Buffering of genetic regulatory networks in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2016, 203, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-g.; et al. Effect of curcumin on aged Drosophila Melanogaster: a pathway prediction analysis. Chinese journal of integrative medicine 2015, 21, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; et al. Neuroprotective properties of phytochemicals against paraquat-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Pesticide biochemistry and physiology 2012, 104, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedara, A.O.; et al. An assessment of the rescue action of resveratrol in parkin loss of function-induced oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, S.; et al. Dietary resveratrol does not affect life span, body composition, stress response, and longevity-related gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grondin, J.A.; et al. Mucins in intestinal mucosal defense and inflammation: learning from clinical and experimental studies. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.H. and R.J. Seeley, Reg3 proteins as gut hormones? Endocrinology 2019, 160, 1506–1514. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrese, E.L. and J.L. Soulages, Insect fat body: energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annual review of entomology 2010, 55, 207–225. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 1 Expression Promotes Chemoresistance in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.E., A.G. Vaughan, and R.I. Wilson, A mechanosensory circuit that mixes opponent channels to produce selectivity for complex stimulus features. Neuron 2016, 92, 888–901. [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Annotation | Human Orthologue | Disease | Plant Extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBgn0003079 | Raf | Encodes a serine-threonine protein kinase; it activates the MEK/ERK pathway to regulate cell proliferation. | Raf-1 | Cancer | Phaseolus vulgaris |

| FBgn0032049 | Bace | Beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme encodes an aspartic protease that cleaves amyloid precursor proteins. | BACE1 | Alzheimer | Pueraria tuberosa |

| FBgn0026420 | SNCA | Engineered foreign gene involves several processes, including negative and positive transport regulation and protein metabolic process. | SNCA | Parkinson | Lemongrass |

| FBgn0285944 | para | A gene is required for locomotor activity. It encodes an α-subunit of voltage-gated sodium channels. | SCN | Epilepsy | Imperata cylindrica |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).