1. Introduction

Clubfoot, also known as congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) is one of the most common congenital musculoskeletal deformities. The prevalence of clubfoot births in Africa is estimated to be 1.11 (95 percent CI 0.96–1.26) per 1000 live births [

3]. The Global Clubfoot Initiative (GCI) (a not-for-profit collaborative initiative) estimates that around 174,000 infants are born with clubfoot each year, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) accounting for 91 percent of those affected. The Ponseti technique of treatment, which is primarily non-surgical, can successfully treat clubfoot in up to 95 percent of cases [

4].

The Ponseti technique of treatment is divided into two stages for treating infant clubfoot. In the first phase, foot deformity correction is performed with foot manipulation and weekly plaster cast changes. The cavus deformity is treated first, followed by the adductus deformity. When the talar head is covered, a percutaneous Achilles tendon tenotomy is usually performed to correct the ankle equinus. In the second (maintenance) phase, the corrected position of the clubfoot is maintained using a Foot Abduction Brace (FAB) to prevent relapse of the deformity. The FAB is worn for 23/24 hours for the first 12 weeks, and thereafter during sleep until the child is 4–5 years old [

5].

A major barrier to the provision of clubfoot treatment in Africa is the critical shortage of healthcare providers [

6] and a lack of providers’ knowledge and skills [

7]. The authors of that study conclude that ‘structured training programs that support conservative manipulative methods to manage CTEV should be initiated globally’. To address this need, a health partnership was established between the University of Oxford, CURE Children’s Hospital of Ethiopia, CURE Clubfoot and GCI. In 2017, they developed the Africa Clubfoot Training (ACT) basic and advanced provider courses, which have standardized the delivery of clubfoot training in Africa. These courses have been rolled out across the continent in English, French and Portuguese. The two courses focus on the Ponseti method of treatment for children under two years and course feedback has indicated a need for more training on treatment of the older child with clubfoot.

Treatment of delayed presenting clubfoot is more challenging in older children and in those with greater deformity [

8]. ‘Delayed presenting clubfoot’ (DPC) refers here to clubfoot abnormalities, of idiopathic cause, present at birth and not treated before walking stage [

2]. We use ‘Delayed Presenting Clubfoot’ (DPC) in this paper as a preferred nomenclature as the term ‘neglected clubfoot’ infers a degree of blame and deliberate inaction. DPC is common in LMICs, particularly in rural and remote places, due to a lack of access to clubfoot treatment. The rigidness of the deformity increases as a child gets older in part due to the changing viscoelastic properties of the soft tissues and in part as the bony skeleton matures. While the Ponseti method is proven to be extremely effective at managing clubfoot when used early in life, particularly in infancy, there is comparatively less published literature on DPC. However, there are a growing number of reports of older children being successfully treated utilising Ponseti principles of management [

9,

10,

11].

In 2020, the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS) at University of Oxford and CURE Children’s Hospital of Ethiopia were awarded a project grant from the Tropical Health Education Trust (THET) Africa Mother & Child Grants Programme, funded by Johnson & Johnson Foundation Scotland to develop a training course for treatment and surgical care for walking children with DPC in Ethiopia (referred to in this study as ‘the project’), as a follow-on course from the ACT basic and advanced provider courses. The project team reviewed lessons learned from the process evaluation of the development of the ACT provider courses and undertook formative research to inform the design of the DPC course content.

The objectives of this formative research study were to:

- explore current treatment techniques and approaches for management of older children with clubfoot, to gain insight on all aspects of care within a multidisciplinary team, including typical pitfalls;

- identify areas of management consensus as well as to define controversial aspects that would be useful for future research projects;

- inform the development of a new training course on management of DPC in a resource limited setting.

This paper uses the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guideline for reporting qualitative research [

12].

2. Materials and Methods

Limited published data exists on current practice and practitioners’ rationale for DPC management approaches. We used a mixed-methods approach for this formative research study to gain a deeper understanding of current management of DPC that could influence the design of a new training course. We conducted an online cross-sectional self-reported survey among clubfoot practitioners, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive context for treatment decisions. The survey included multiple choice questions to collect measurable data on frequency or preferences for various management options. Additionally, we used an inductive descriptive qualitative approach to investigate the complex views and beliefs related to decision-making processes related to DPC management options, and to understand clinical and contextual reasons for these.

The multi-disciplinary study team included the project directors (CL and TN, both consultant orthopaedic surgeons), project manager (GD), two children’s physiotherapists (TS and Rosalind Owen), and a research coordinator (FD) based at CURE Children’s Hospital of Ethiopia. CL, TN, RO and TS all have direct experience of clubfoot treatment, training and research in the UK and Africa over the past 15 years. TN is based at the largest children’s orthopaedic service in Ethiopia which receives referrals from across the country and treats around 120 children with DPC per year. Some of the survey respondents were known to members of the study team through professional networks and collaboration on regional training and service delivery; therefore, the data were anonymised for data collection and analysis.

The study aimed to include practitioners from various disciplines regularly treating older children with clubfoot in a LMIC setting. This encompassed surgeons, doctors, physiotherapists and clinical officers, as clubfoot care may be provided by different cadres in settings with limited resources and a scarcity of trained providers. The team also sought to understand the multidisciplinary factors influencing DPC treatment at different stages. The project team decided to target the survey invitation to experienced practitioners to increase the validity and quality of responses and to more efficiently analyse the volume of data from the detailed survey. The project team identified 20 experienced clubfoot practitioners known professionally to the team through regional clubfoot training collaboration. One of the study project partners, Global Clubfoot Initiative (representing over 30 organisations involved in clubfoot service delivery and training in LMICs), also cascaded an invitation to the survey through its member organizations requesting practitioners experienced in treating older children with clubfoot to participate. GCI also specifically invited the 18 members of the Global Clubfoot Initiative Advisory Board to complete the survey. Due to time and resource constraints, the survey was conducted in English only. Although the training course was designed primarily for use in Ethiopia and piloted in Addis Ababa, we included responses from all countries where DPC is commonly seen.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as assessed by the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee protocol, University of Oxford. The data were anonymised for the purpose of data analysis. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

We selected an electronic survey as a data collection tool using multiple choice questions to collect data with measurable variables on preferred casting, surgical and rehabilitation techniques, and open text questions to collect qualitative data to help understand the context in which these decisions are taken. The cross-sectional survey enabled us to collect consistent data over the same time frame i.e. in parallel with the course content design.

We included questions on all phases of multidisciplinary management of delayed presenting clubfoot, based on data provided by Global Clubfoot Initiative from a 2018 pilot project surveying referral pathways and rehabilitation protocols in low resource settings for the older child with clubfoot, and from trainers’ feedback from the teaching session on treatment of older children in the ACT advanced course. We accordingly divided the survey into sections on decision-making, casting, the role of imaging, type of surgery and need for orthotics, rehabilitation and post-operative management, multi-disciplinary approach and contextual factors.

We refined the scope of the survey to management protocols for children aged 2-10 years with congenital idiopathic clubfoot that can benefit from the principles of the Ponseti technique. ‘Ponseti principles’ is here defined as serial casting to achieve foot correction starting with cavus elimination followed by adduction correction, followed by surgical correction of equinus at the ankle. This survey excluded protocols for patients who had skeletally mature feet, had cast resistant clubfoot following extensive correction casts, severe deformity that required osteotomies or arthrodesis, or external fixation treatment of residual deformity. Further exclusions were protocols for syndromic or neurogenic clubfoot.

We undertook a cross-sectional electronic survey between 12 October and 10 November 2020 using JISC Online Surveys platform. The project directors CL and TN sent the survey by email invitation to 38 experienced practitioners (20 practitioners selected by the study team through professional experience, and 18 Global Clubfoot Initiative Advisory Board members). Global Clubfoot Initiative also sent the survey invitation to 50 member contacts to cascade directly to experienced practitioners worldwide. The collected survey data was held on a secure survey platform.

There were 50 survey respondents out of 88 contacts who were sent the survey, which is a response rate of 56.8%. Forty-nine of the respondents currently treated older children with clubfoot. The one respondent who did not currently treat older children had recent clinical experience with DPC as a visiting surgeon in a low-resource setting and therefore the study team decided to include this response due to relevant experience. Participant demographics are shown in

Figure 1 in Results.

We evaluated both qualitative and quantitative data to gain a deeper understanding of the research findings. The quantitative data were analysed by FD and TN using descriptive statistics where appropriate. GD, TN and FD collated the responses to the open-ended questions into a word document and undertook a qualitative content analysis using the questions as the codes. We grouped similar responses, titled these, and counted the number of responses. Using conventional content analysis, coding groups were derived directly from the text data. We analysed qualitative questions thematically and undertook a narrative description of themes raised in the electronic survey.

The survey data were summarized and presented in written format to the project’s multidisciplinary technical advisory group (composed of invited highly experienced trainers in management of DPC in low-resource settings) and project stakeholders’ group in December 2020. We held online meetings with these two focus groups to review common survey results themes for triangulation, asking them to verify the accuracy or resonance with their perspectives, and to determine which management aspects would be appropriate in developing the DPC course.

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

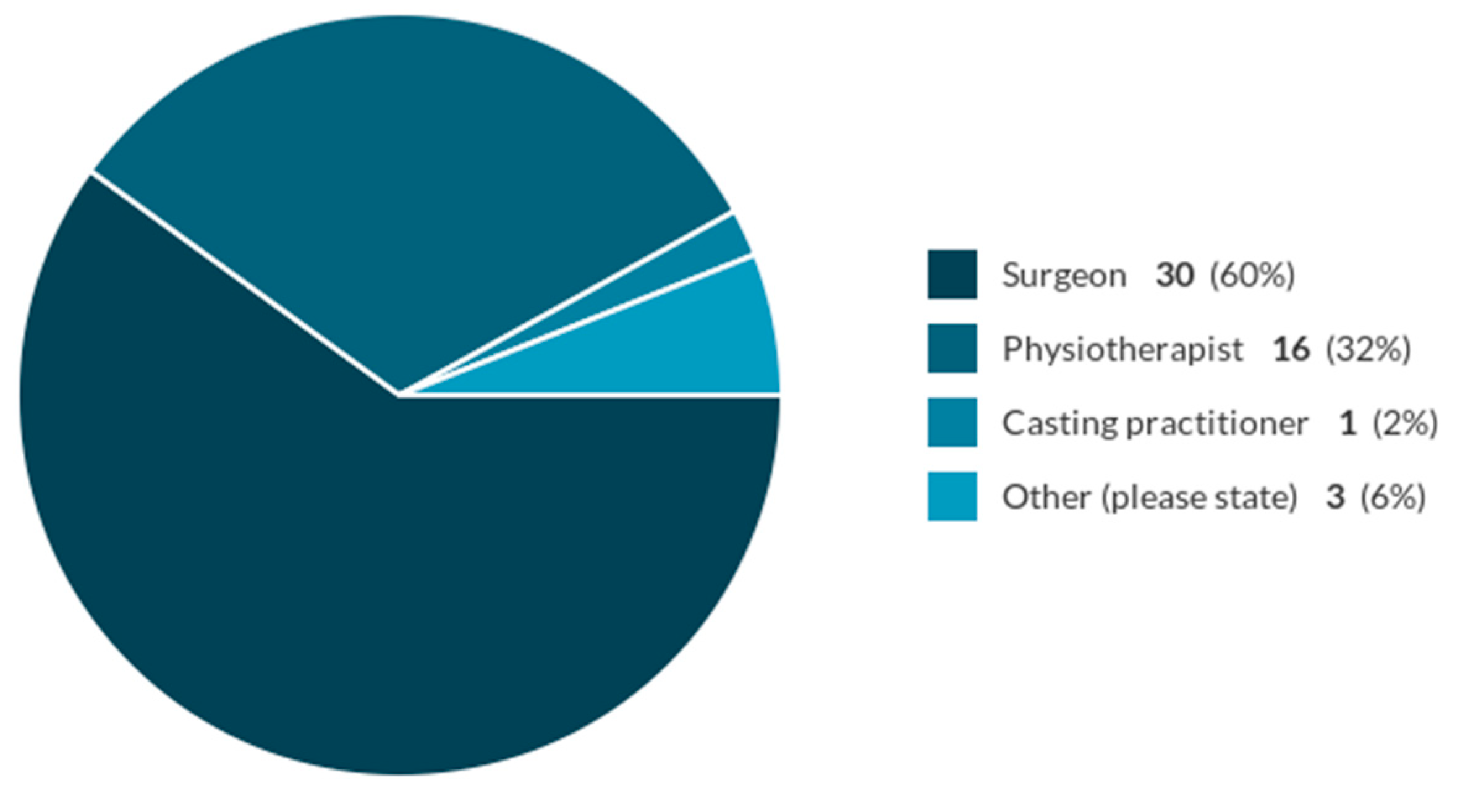

There were 30 (60%) surgeons, 16 (32%) physiotherapists, 1 (2%) casting practitioner and 3 (6%) ‘other’ respondents to the survey (see

Figure 1).

Thirty-seven of the respondents specified their country of work (here listed in alphabetical order): Australia, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mali, Mexico, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Norway, Philippines, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Spain, Tanzania, United Kingdom, United States of America, and Zimbabwe. The remaining thirteen did not specify. The most common country of work cited was ‘Ethiopia’ (7 respondents).

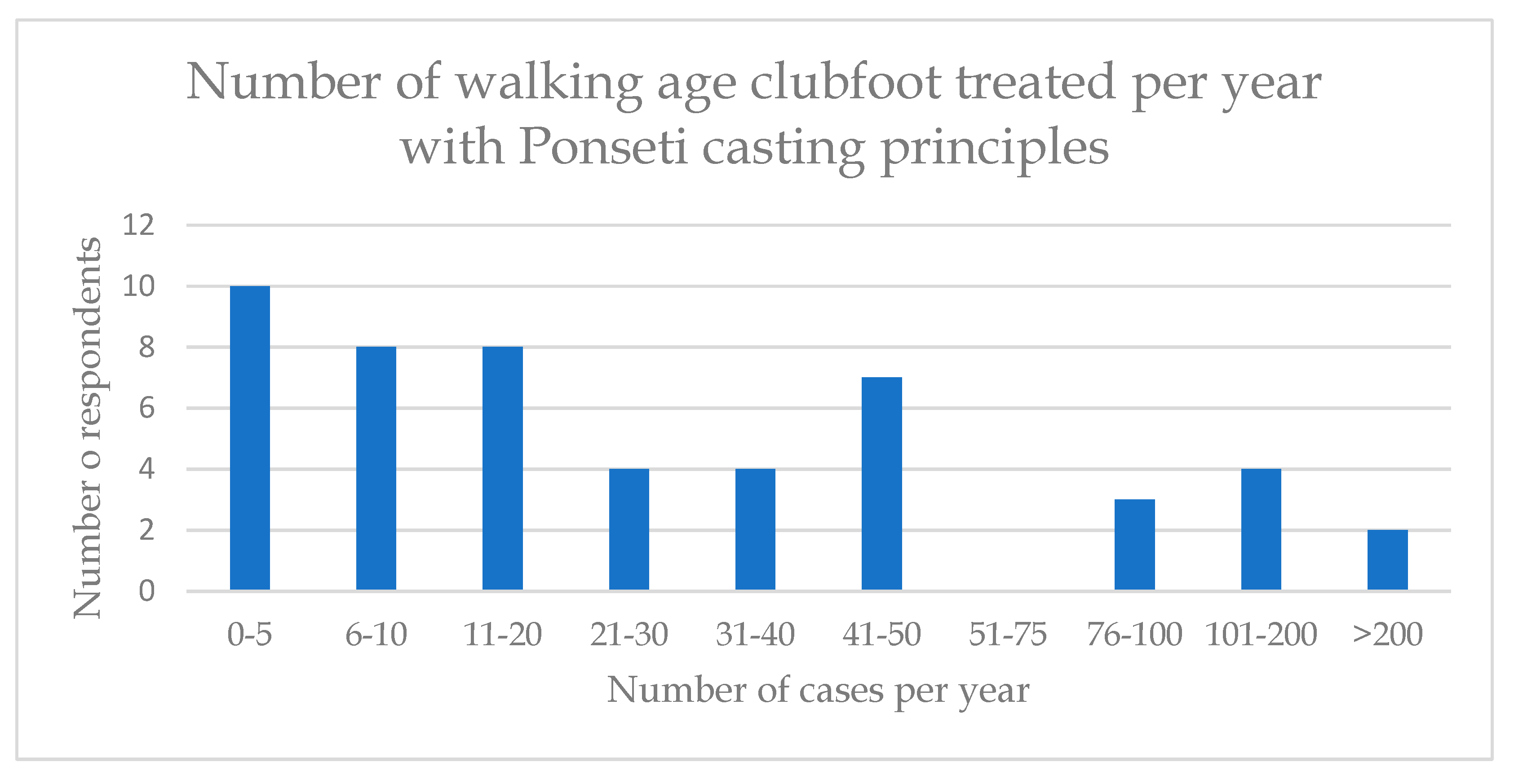

The number of DPC cases treated by the respondents per year were quite variable (

Figure 2).

3.2. Decision-making

During assessment, most practitioners reported that they would try to evaluate the severity of the deformity and the clubfoot flexibility. Practitioners also stated that they reviewed the spine, the neurological status, the tendon motors function the foot, the standing position of the foot and the walking pattern. The scoring systems that respondents most commonly used to assess children with DPC were the Pirani score (cited by 22 respondents), followed by the PAVER score (cited by 15 respondents). Several respondents noted that, although the Pirani score was used, it was not designed, validated, or well suited for the walking child.

Practitioners also factored in several contextual considerations when making treatment decisions. These considerations included the patients’ distance from the facility, patients’ financial situation, home environment, nutritional evaluation, damage to cast, and factors related to the patient dropping out of treatment or missing follow-up appointments.

3.3. Casting

Long leg casts were favoured by a large majority of respondents 83.7% (n=41) instead of short leg casts. Most respondents 54% (n=27) gave non-weight bearing instructions, whilst 20%(n=10) recommended weight-bearing and 26% (13) said it depended, for example, on factors such as age, mobility, family circumstances. Children who have bilateral clubfoot can have both treated at the same time and 82% (n=41) of respondents would prefer this. Social factors, schooling and the size of the child were amongst reasons cited for sequential correction of bilateral clubfeet.

The commonest cast change interval was weekly (48%, n=24), followed by a cast change every 2 weeks (40%, n=20). Again, age of the child and social factors were qualifiers in the responses, with advice for younger children to receive weekly cast changes. Respondents defined indications of a ‘successful cast’ in terms of correction of deformity, a plantigrade foot, and reduction of the talar head.

We asked respondents when they would ‘abandon casting and pronounce the foot as “cast resistant”’. There was a range of answers and no clear consensus on number of casts attempted or maximum duration for serial casting but, in general, practitioners were looking to see progress with deformity correction through serial casting and would stop when they did not see any further improvement.

3.4. Orthotics

When we asked practitioners if they recommend orthotics, 84% (n=42) said ‘yes’, 12% (n=6) said ‘no’, and 4% (n=2) said they ‘don’t know’. Some qualified their response according to whether they believed there was going to be compliance, whether the facility was available, or a tendon balancing procedure was performed. Foot abduction braces (FABs) and ankle foot orthoses (AFOs), used as night splints were common orthotic preferences.

3.5. Surgical options

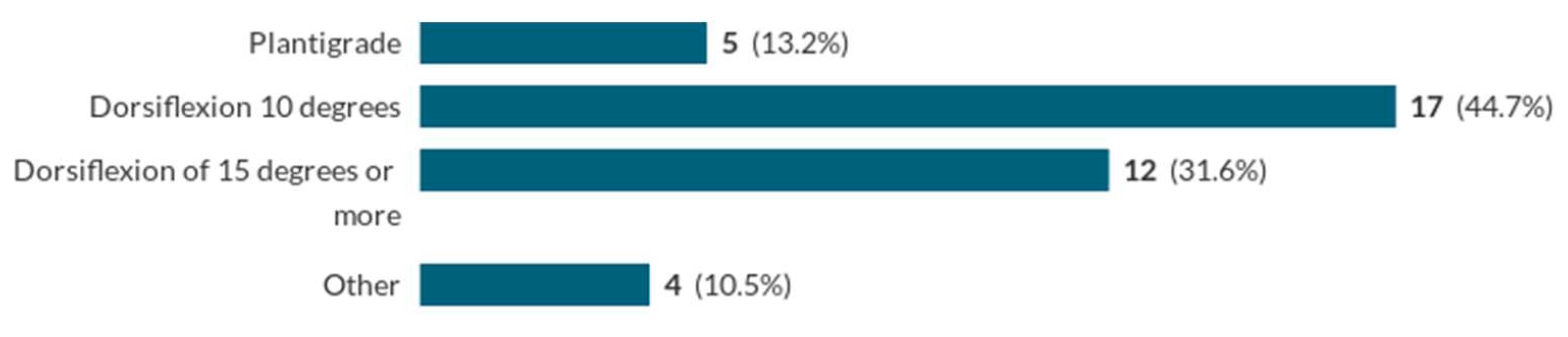

Respondents were asked about the dorsiflexion goal of surgical correction of the equinus deformity. An ability to achieve the dorsiflexion goal of 15 degrees was seen as satisfactory (see

Figure 3):

If the dorsiflexion goal was not achieved, the most common response (cited by eight practitioners) was to perform serial casting again, followed by managing the problem with osteotomies (cited by six practitioners). Posterior ankle capsular release is ‘always’ included in the protocol of 7.9% (3) practitioners, ‘sometimes’ in 68.4% (n=26), and ‘never’ in 15.8% (n=6). 35.1% (n=13) of respondents perform cast wedging to gain further dorsiflexion and 59.5% (n=22) do not do this.

The most commonly suggested indications for Tibialis Anterior Tendon Transfer following full correction (TATT) were dynamic supination (cited by 4 respondents) and expected low compliance with bracing in their setting (cited by 3 respondents). Eleven out of 18 respondents (61.1%) would transfer the tendon in a TATT to the lateral cuneiform; with a few respondents opting for the intermediate cuneiform.

Regarding preferred technique for Achilles tendon lengthening,18.4% (n=7) of respondents use Achilles tendon lengthening, 23.7% (n=9) use tenotomy, and 57.9% (n=22) of respondents use either technique.

3.6. Imaging

47.4% (n=18) of respondents use pre-operative imaging; 52.6% (n=20) do not. Of the 50% (n=19) of respondents who perform Tibialis Anterior Tendon Transfer following full correction (TATT), 36.8% (n=7) use intra-operative imaging whereas 63.2% (n=12) do not. For clubfeet with resistant equinus, the use of lateral radiographs or intraoperative fluoroscopy was suggested as helpful. This helps by defining the cause, which could be due to a hidden midfoot cavus/plantaris deformity which can be difficult to clinically appreciate.

3.7. Anaesthesia

65.8% (n=25) respondents use general anaesthesia for Achilles tendon lengthening for children aged 2-10, 13.2% (n=5) use local anaesthesia, and 21.1% (n=8) said ‘it depends’. There was no common theme in the reasons given for different anaesthesia choices. It was unclear from the responses if there was a consensus on age threshold for the use of general anaesthesia.

3.8. Recurrence

82% (n=41) of respondents said that they had seen recurrences of the clubfoot deformity and 12% (n=6) had seen over-corrections in DPC management. (Findings from a study in New Zealand similarly reported recurrence as a common problem, where twenty-one (41%) of the fifty-one patients had a recurrence, which was major in twelve of them and minor in nine [

13]. The most common cause of deformity recurrence (suggested by 34% (n=17) of respondents) was the lack of adherence to the treatment protocol. Other factors commonly suggested were that patients were lost in follow-up, or that the clubfoot may have been under-corrected. The most common management approach for DPC recurrence cases was to perform serial casting again and surgery.

3.9. Rehabilitation and post-operative management

52% (n=26) of respondents perform post-operative casting, whereas 38% (n=19) did not. Of those who do post-operative casting, both the mean and median time point post-operation for changing the cast was two weeks. In terms of post-surgery weight bearing status in cast, 63.2% (n=24) of respondents would recommend non-weight bearing, 26.3% (n=10) would recommend ‘weight bearing as tolerated’, and 10.5% (n=4) would recommend partial weight-bearing.

The most common rehabilitation exercises suggested focused on strengthening and improving the flexibility of the foot and ankle. These exercises aimed to enhance range of motion, muscle strength, and proprioception. Specific stretches included those for the calf muscles. Other exercises involved toe curls, ankle range of motion exercises, and balancing activities to improve stability. There was some focus on rehabilitation exercises for the whole child, including core and hip strength.

3.10. Multi-disciplinary approach

Most practitioners recommended that Multi-Disciplinary Teams (MDT) (which may include surgeons, physiotherapists, doctors, orthotists and social workers) are involved in the management of older children with clubfoot, with a team approach to planning, decision-making, follow-up and rehabilitation. Respondents suggested that the most important process for enhancing a multidisciplinary approach is frequent collaborative team communication throughout the treatment pathway, extending to clear communication to parents and caregivers.

4. Discussion

The study included responses from 50 participants, including surgeons, physiotherapists, and casting practitioners from high-, middle-, and low-income countries, representing a total of over 23 countries. Information provided by respondents highlights key findings regarding decision-making, casting, orthotics, surgical options, imaging, anesthesia, recurrence, rehabilitation, and the multidisciplinary approach in the management of clubfoot deformity in older children. Regarding decision-making, practitioners consider various factors during assessment, indicating a comprehensive approach. However, the limitations of the Pirani score for walking children are acknowledged, suggesting the need for more suitable assessment tools. The consideration of contextual factors reflects a holistic approach to treatment planning. The majority of practitioners recommend orthotics, particularly foot abduction braces (FABs) and ankle foot orthoses (AFOs). This emphasises the view that it is important to provide external support to maintain correction and facilitate proper foot positioning. The range of surgical options available indicates a tailored approach based on individual cases, with an emphasis on achieving dorsiflexion goals and addressing specific deformities. The utilisation of pre-operative and intra-operative imaging varies among practitioners, suggesting a lack of consensus on their necessity. Anaesthesia choices for Achilles tendon lengthening vary, with general anesthesia being the most common approach. The recurrence of clubfoot deformity and over-corrections indicate the challenges in long-term management, with non-adherence to treatment protocols being a prominent factor. Serial casting and surgery are the main strategies for managing recurrence cases.

Whilst the numbers of patients presenting with DPC is small in high-income settings, the volume of cases is significant in low-income countries where healthcare provision is limited. Respondents from low-income countries had a large volume and experience of this treatment. In combination with the prevalence of this untreated condition, the social factors for prolonged treatment and disruption to families and livelihoods are also disproportionately higher in the low-income settings. Contextual factors, including social and family issues are therefore much more relevant in these settings and are large influences on the choice of treatment options [

14]. As we saw clearly from the survey, decisions on timing of treatment start, timing of cast change, bilateral treatment are closely related to the availability of accommodation close to the treatment facility and ability to access to care throughout the serial casting, surgical and rehabilitation phases. In terms of assessment of the clubfoot deformity, the continued use of the Pirani score for assessment of clubfoot in older children was a surprise to the study team, as many of the components of the score are not relevant to older children of walking age, which was also noted by several respondents. (For example, posterior creases are not seen in this population, medial plantar creases are uncommon, and differentiation of the ‘empty heel’, different degrees of ‘curved lateral boarder’ and ‘talar head coverage’ are all poorly discriminating factors in walking age children.)

We observe there is variation in DPC casting protocols in terms of short and long leg casts, how many serial casts are attempted, instructions on weightbearing, and whether bilateral feet are treated at the same time or sequentially, and how these are related to important contextual factors such as child’s age, size, mobility, the strength of caregivers (to lift a child), family and socio-economic situation, and schooling. The preferred cast change interval time is usually every one or two weeks. Despite the variations in technique, in general, practitioners are applying principles of the Ponseti method to sequentially correct the clubfoot deformity as far as possible with long leg serial casting and manipulation. Contextual factors also influenced the variability of the use of orthotics and the need for a Tibialis Anterior Tendon Transfer (TATT) to the lateral cuneiform, with reasons provided for the use of each according to availability and perceptions about compliance. For example, patients who were traveling long distances at great expense would not be able to afford a continued orthotic management regime.

The survey results identify key physiotherapy exercises whilst casting and following removal of cast to aid fast and optimal recovery, especially for bilateral clubfoot cases. This is important as children with clubfoot have a specific way of walking that aims to compensate for their condition. They may walk with their knees in hyperextension and their pelvis tilting forward, which causes their lower back to arch. This happens because their center of gravity has shifted backward, and their feet and ankles do not provide enough push. As a result, their core muscles and foot muscles become weak. After being treated with casts, clubfoot patients not only need to regain their muscle strength, but also work on their core muscles. The survey results underline the importance of a holistic and multidisciplinary approach, including physiotherapy involvement, through all phases of treatment planning, deformity correction, maintenance phase and rehabilitation.

These survey findings contribute to the collective knowledge and understanding on existing practice of multidisciplinary treatment of clubfoot in older children in resource-limited settings. The formative research findings have been reviewed by the study team, project technical advisory group and project stakeholders group to triangulate data to influence the design of content of a training course on Principles of Management for Delayed Presenting Clubfoot (in walking age children 2-10 years). This new interactive course dovetails with existing training courses on clubfoot in infants, and it meets a key training need identified by regional expert trainers. The one-day course was piloted in 2021, completed in 2022, and has since been rolled out in Ethiopia to train physiotherapists, doctors and surgeons. Further roll-out of training DPC courses in sub-Saharan Africa is planned through Global Clubfoot Initiative partners.

We suggest further research may be beneficial on areas where there is no consensus and/or limited evidence base, such as rehabilitation exercises in or out of post-op casts, management approaches for recurrence, use of orthotics, whether there is a maximum age for weekly cast changes, criteria and evidence for treating bilateral clubfeet at the same time or sequentially, identifying causes of recurrence and best management options, and documenting adaptive gait disturbances in clubfoot and efficacy of directed physiotherapy interventions.

As the survey was undertaken in English only, the results are limited in that they do not reflect experiences of French or Portuguese-speaking practitioners in Africa. The sample for some of the questions is smaller (e.g. the surgical technique questions that were not applicable to all respondents) which may reduce the generalizability of these results, therefore we have stated number counts as well as percentages. Selection bias could be present due to the sampling strategy to target known experienced practitioners, however the cascaded invitation through Global Clubfoot Initiative members sought to provide opportunity to collect a broader range of experienced practitioners. Interpretation bias could be present as some of the study team and technical advisory group have previously developed and published protocols on management of DPC using Ponseti principles; however, we have sought to mitigate this through inclusion of researchers and focus group participants who have not been involved.

5. Conclusions

The survey findings identify key areas of consensus in the overall principles of management for delayed presenting clubfoot in walking age children and the implementation of Ponseti principles for this patient group. Some differences that exist in the approach may reflect adaptations by practitioners to the surgical and rehabilitation resources available in the local context and the socio-economic situation of the patient and the family. Although the technique for DPC management is not yet standardized, the experience of the practitioners surveyed demonstrate how the principles can be adapted well for different geographical and healthcare contexts and tailored to the context of the patient and family, as part of a holistic and flexible approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TN, GD, CL; Methodology, TN, TS, GD; Validation, GD, TN; Formal Analysis, GD, TN, FD, TS; Investigation, TN, GD.; Resources, GD.; Data Curation, GD, TN; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, TN; Writing – Review & Editing, TN, GD, CL, TS, FD.; Supervision, CL; Project Administration, GD. All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Funding

This research is an output from the Africa Mother and Child Grants Programme Fund, funded by the Johnson & Johnson family of companies for the benefit of the UK and partner country health sectors, and managed by Tropical Health Education Trust. The views expressed are not necessarily those of Johnson & Johnson or THET. This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), UK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as assessed by the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee protocol, University of Oxford.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, GD. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Global Clubfoot Initiative for assistance in distribution of the survey, all the practitioners who participated, and the technical advisory group and project stakeholders group who voluntarily gave their time to review the survey findings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Johnson & Johnson family of companies. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Dyer PJ, Davis N. The role of the Pirani scoring system in the management of club foot by the Ponseti method. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006, 88, 1082–1084. [CrossRef]

- Nunn TR, Etsub M, Tilahun T, et al. Development and validation of a delayed presenting clubfoot score to predict the response to Ponseti casting for children aged 2–10. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Smythe T, Kuper H, Macleod D, Foster A, Lavy C. Birth prevalence of congenital talipes equinovarus in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Cooper DM, Dietz FR. Treatment of idiopathic clubfoot: A thirty-year follow-up note. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1995, 77. [CrossRef]

- Ponseti, IV. Treatment of congenital club foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992, 74, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancedda C, Farmer PE, Kerry V, et al. Maximizing the Impact of Training Initiatives for Health Professionals in Low-Income Countries: Frameworks, Challenges, and Best Practices. PLoS Med. 2015, 12. [CrossRef]

- Johnson RR, Friedman JM, Becker AM, Spiegel DA. The Ponseti Method for Clubfoot Treatment in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Solutions to Service Delivery. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2017, 37. [CrossRef]

- Adegbehingbe OO, Adetiloye AJ, Adewole L, et al. Ponseti method treatment of neglected idiopathic clubfoot: Preliminary results of a multi-center study in Nigeria. World J Orthop. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço AF, Morcuende JA. Correction of neglected idiopathic club foot by the Ponseti method. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series B. 2007, 89. [CrossRef]

- Ayana B, Klungsøyr PJ. Good results after Ponseti treatment for neglected congenital clubfoot in Ethiopia. A prospective study of 22 children (32 feet) from 2 to 10 years of age. Acta Orthop. 2014, 85. [CrossRef]

- Mehtani A, Banskota B, Aroojis A, Penny N. Clubfoot Correction in Walking-age Children: A Review. Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery (Asia Pacific). 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine. 2014, 89. [CrossRef]

- Haft GF, Walker CG, Crawford HA. Early clubfoot recurrence after use of the Ponseti method in a New Zealand population. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2007, 89. [CrossRef]

- Pinto D, Agrawal A, Agrawal A, Sinha S, Aroojis A. Factors Causing Dropout From Treatment During the Ponseti Method of Clubfoot Management: The Caregivers’ Perspective. Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2022, 61. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).