Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

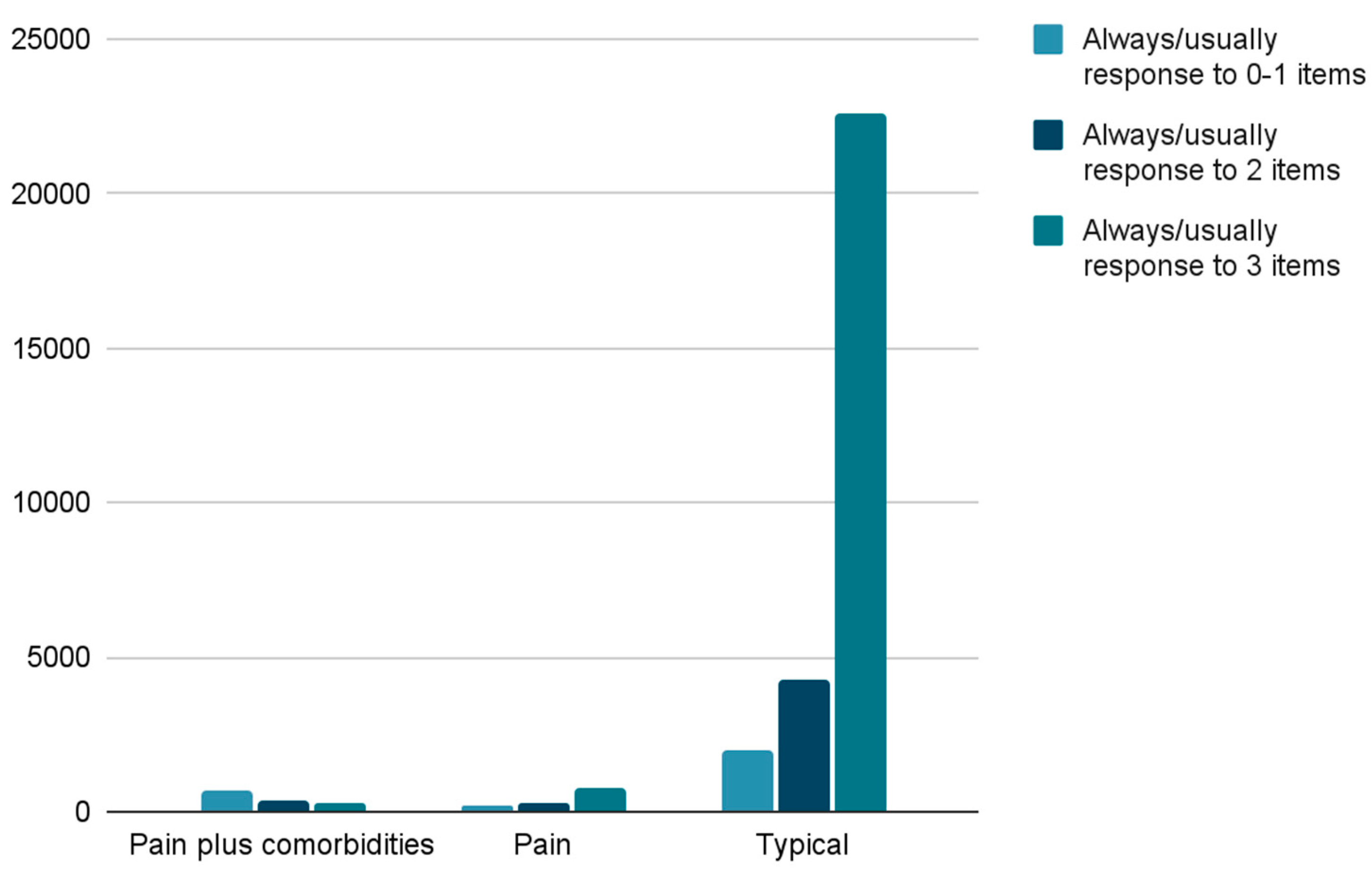

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Unique Nature of Pediatric Chronic Pain

1.2. Chronic Pain and Emotional, Developmental, or Behavioral Comorbidities

1.3. Flourishing and Chronic Pain

1.4. Objective and Aims

2. Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables and Measures

2.3.1. Chronic Pain Condition Status Groups

2.3.2. Flourishing Categories

2.3.3. Predictors

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. (2020). Guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017870.

- Groenewald, C.B.; Tham, S.W.; Palermo, T.M. Impaired school functioning in children with chronic pain: A national perspective. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2020, 36, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, B.W.; et al. Managing chronic pain in children and adolescents: a clinical review. PM&R 2015, 7, S295–S315. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, T.M. Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: a critical review of the literature. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 2000, 21, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Konijnenberg, A.Y.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; Kimpen, J.L.L.; van der Hoeven, J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; de Graeff-Meeder, E.R. Children with unexplained chronic pain: substantial impairment in everyday life. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2005, 90, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunfeld, J.A.M.; Passchier, J.; Perquin, C.W.; Hazebroek-Kampschreur, A.A.J.M.; van Suijlekom-Smit, L.W.A.; Van Der Wouden, J.C. Quality of life in adolescents with chronic pain in the head or at other locations. Cephalalgia 2001, 21, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Eccleston, C. Parents of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain 2009, 146, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Chambers, C.T.; Huguet, A.; MacNevin, R.C.; McGrath, P.J.; Parker, L.; MacDonald, A.J. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011, 152, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccleston, C.; Malleson, P. Managing chronic pain in children and adolescents. BMJ 2003, 326, 1408–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perquin, C.W.; Hazebroek-Kampschreur, A.A.; Hunfeld, J.A.; Bohnen, A.M.; van Suijlekom-Smit, L.W.; Passchier, J.; Van Der Wouden, J.C. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain 2000, 87, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.M.; Meints, S.M.; Hirsh, A.T. Catastrophizing, pain, and functional outcomes for children with chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Pain 2018, 159, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, G.D.; et al. Functional abdominal pain in childhood and long-term vulnerability to anxiety disorders. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotopf, M.; Carr, S.; Mayou, R.; Wadsworth, M.; Wessely, S. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up? Population-based cohort study. BMJ 1998, 316, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Rapoff, M.A.; Waldron, S.A.; Gragg, R.A.; Bernstein, B.H.; Lindsley, C.B. Chronic pain and emotional distress in children and adolescents. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 1996, 17, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Vinall, J.; Pavlova, M.; Asmundson, G.J.; Rasic, N.; Noel, M. Mental health comorbidities in pediatric chronic pain: a narrative review of epidemiology, models, neurobiological mechanisms and treatment. Children 2016, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.D.; McParland, J.L.; Halligan, S.L.; Goubert, L.; Jordan, A. Flourishing among adolescents living with chronic pain and their parents: A scoping review. Paediatric and Neonatal Pain 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2002, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, T.; Fraser, E.; Edmunds, S.; Wilkinson, N.; Jacobs, K. Journeys of adjustment: the experiences of adolescents living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Child: Care, Health and Development 2015, 41, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccleston, C.; Wastell, S.; Crombez, G.; Jordan, A. Adolescent social development and chronic pain. European Journal of Pain 2008, 12, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Neville, A.; Hurtubise, K.; Hildenbrand, A.; Noel, M. Finding silver linings: A preliminary examination of benefit finding in youth with chronic pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2018, 43, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinajero, C.; Páramo, M.F. The systems approach in developmental psychology: Fundamental concepts and principles. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 2012, 28, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, S.W.; Law, E.F.; Palermo, T.M.; Kapos, F.P.; Mendoza, J.A.; Groenewald, C.B. Household Food Insufficiency and Chronic Pain among Children in the US: A National Study. Children 2023, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corser, J.; Caes, L.; Bateman, S.; Noel, M.; Jordan, A. ‘A whirlwind of everything’: The lived experience of adolescents with co-occurring chronic pain and mental health symptoms. European Journal of Pain 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubert, L.; Trompetter, H. Towards a science and practice of resilience in the face of pain. European Journal of Pain 2017, 21, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 2013, 139, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Chronic Pain Plus | Chronic Pain | Typical Peers | χ2 | Cramer’s V |

| Age, years | -.10abc | .10 | |||

| 6 – 11 years | 355 (27.9%)c | 315 (26.0%) | 12991 (44.9%) | ||

| 12 – 17 years | 918 (72.1%) | 896 (74.0%) | 15960 (55.1%) | ||

| Sex | 63.98b | .05 | |||

| Male | 355 (27.9%)c | 315 (26.0%) | 12991 (44.9%) | ||

| Female | 918 (72.1%) | 896 (74.0%) | 15960 (55.1%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 43.98b | .03 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic |

907 (71.2%) | 872 (72.0%) | 19912 (68.8%) | ||

| Hispanic | 143 (11.2%) | 121 (10.0%) | 3485 (12.0%) | ||

| Black Non-Hispanic |

110 (8.6%) | 97 (8.0%) | 1832 (6.3%) | ||

| Other/ multi-racial, non-Hispanic |

113 (8.9%) | 121 (10.0%) | 3722 (12.9%) | ||

| Working Poor | 9.02d | .02 | |||

| Working Poor | 111 (4.6%) | 118 (4.9%) | 2192 (90.5%) | ||

| Not Working Poor |

1140 (4.0%) | 1075 (3.8%) | 26097 (92.2%) | ||

| Poverty Level | .08ab | .07 | |||

| 0-99% FPL | 248 (19.5%) | 198 (16.4%) | 3013 (10.4%) | ||

| 100-199% FPL | 304 (23.9%) | 246 (20.3%) | 4456 (15.4%) | ||

| 200-399% FPL | 357 (28.0%) | 369 (30.5%) | 9043 (31.2%) | ||

| >400% FPL | 364 (28.6%) | 398 (32.9%) | 12439 (43.0%) | ||

| Parental education | .06ab | .05 | |||

| Less than high school | 41 (3.2%) | 36 (3.0%) | 823 (2.8%) | ||

| High school or GED | 206 (16.2%) | 204 (16.8%) | 3846 (13.3%) | ||

| Some college or technical school | 434 (34.1%) | 340 (28.1%) | 6704 (23.2%) | ||

| College degree or higher |

592 (46.5%) | 631 (52.1%) | 17578 (60.7%) | ||

| Health Insurance | 887.64b | .12 | |||

| Public insurance only |

466 (36.9%) | 328 (27.4%) | 4727 (16.6%) | ||

| Private health insurance only |

606 (48.0%) | 750 (62.7%) | 21454 (75.4%) | ||

| Public and private insurance |

152 (12.0%) | 75 (6.3%) | 742 (2.6%) | ||

| Uninsured | 38 (3.0%) | 44 (3.7%) | 1,536 (5.4%) |

| Variable | b | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Constant | -.784 | .096 | 66.67 | <.001 | .457 | ||

| Sex (Male)a | -.308 | .028 | 119.81 | <.001 | .736 | .696 | .777 |

| Age (6-11 years) | -.250 | .028 | 77.73 | <.001 | .779 | .737 | .823 |

| Race/Ethnicity (White) | 20.85 | <.001 | |||||

| Hispanic | -.173 | .043 | 16.01 | <.001 | .841 | .773 | .916 |

| Black | -.018 | .057 | -.10 | .757 | .983 | .879 | 1.098 |

| Other/Multi-racial, non-Hispanic | .064 | .044 | 2.12 | .145 | 1.066 | .978 | 1.162 |

| Poverty (400% FPL or greater) | 50.38 | <.001 | |||||

| 0-99% FPL | -.267 | .055 | 23.87 | <.001 | .766 | .688 | .852 |

| 100-199% FPL | -.228 | .047 | 24.07 | <.001 | .796 | .727 | .872 |

| 200-399% FPL | -.230 | .035 | 42.99 | <.001 | .794 | .742 | .851 |

| Parent Education (College degree or higher) | 172.18 | <.001 | |||||

| Less than high school | -.843 | .080 | 111.69 | <.001 | .430 | .368 | .503 |

| High school or GED | -.404 | .044 | 84.53 | <.001 | .668 | .612 | .728 |

| Some college or technical school | -.293 | .035 | 69.08 | <.001 | .746 | .696 | .799 |

| Health insurance (Uninsured) | 63.76 | <.001 | |||||

| Public health insurance only | -.132 | .065 | 4.16 | .041 | .876 | .771 | .995 |

| Private health insurance only | .192 | .062 | 9.69 | .002 | 1.212 | 1.074 | 1.368 |

| Public and private insurance | -.100 | .093 | 1.17 | .280 | .904 | .754 | 1.085 |

| Pain condition status (Typical) | 1379.61 | <.001 | |||||

| Chronic pain plus | -2.560 | .072 | 1259.52 | <.001 | .077 | .067 | .089 |

| Chronic pain | -8.44 | .063 | 178.68 | <.001 | .430 | .380 | .487 |

| Variable | Initial Model | Full Model |

| Accuracy | 75.4% | 77.8% |

| Not Flourishing | Flourishing | Percentage correct |

|

| Observed | |||

| Not flourishing | 1156 | 6451 | 15.2% |

| Flourishing | 401 | 22885 | 98.3% |

| Overall percentage | 77.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).