Introduction:

Early treatment is one of the pillars of sepsis therapy [

1], with many studies demonstrating worse outcomes when initiation of treatment is delayed [

2,

3]. Sepsis and its resultant long-term sequelae are a leading cause of critical illness and mortality worldwide. Additionally, sepsis and its downstream sequela are associated with high healthcare costs [

4]. Given these high stakes, recently efforts have been made to identify this pathology earlier and reduce the time to initiation of antibiotic therapy. The goal of these efforts is to ultimately reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with sepsis.

Current guidelines recommend administration of antimicrobials immediately, ideally within the first hour, in patients with possible septic shock or high likelihood of sepsis. For patients with possible sepsis but without signs of shock, administration of antimicrobials is recommended within the first three hours after recognition [

1].

To the best of our knowledge, there is no data on whether prehospital suspicion of sepsis - by paramedics, general practitioners or prehospital emergency physicians - shortens time to diagnosis of sepsis and initiation of antibiotic treatment upon arrival to a hospital. We conducted this retrospective study to investigate the suspected prehospital diagnoses for septic patients at the time of presentation to the emergency department, as well as whether suspicion of sepsis by prehospital healthcare personnel was associated with decreased time to antibiotic administration. We hypothesized that a presumed diagnosis of sepsis in the prehospital setting would be associated with a shorter time to antibiotic administration.

Material and Methods:

Study design:

The study was designed as a retrospective cohort study and was conducted between March 2021 and October 2022. We evaluated all patients that were diagnosed with sepsis or a severe infection (possible sepsis) in the emergency department of our institution in the years 2018-2020 for fulfillment of inclusion criteria. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen on 16/09/2020 with the study number 20-9550-BO and had been preregistered in the German Clinical Trials Register on 26/02/2021 under DRKS00022986. The study was carried out in accordance with all relevant regulations and as described by the study protocol. Informed consent was not deemed necessary by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Participants:

We extracted all patients that were diagnosed with sepsis during their hospital stay from our hospital information system (Medico, CompuGroup Medical SE & Co. KGaA, Koblenz, Germany). We included all patients over 18 years of age, that had been diagnosed with sepsis or severe infection (possible sepsis) while in our emergency department. Patients that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded from the study.

Measurements:

We collected data from patients that had been diagnosed with sepsis or severe infection (possible sepsis) in our emergency department. Patient data were extracted from electronic medical record of our emergency department ERPath (eHealth-Tec Innovations GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and from our hospital information system. We recorded whether the patient was admitted to hospital by a general practitioner, emergency medical services (EMS), a prehospital emergency physician or presented by themselves. We also recorded the suspected diagnoses at the time of presentation and the time to initiation of antibiotic treatment as documented by the time the electronic prescription was created by the emergency physician. We also collected gender and age, as well as vital signs data (systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, Glasgow coma scale) to calculate the quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) score.

Outcomes:

Primary endpoint was the suspected prehospital diagnoses, at the time of emergency department arrival, in patients who were later diagnosed with sepsis. Secondary endpoint was the time to antibiotic treatment.

Statistical analysis:

The data was collected and transferred to a spreadsheet in Excel (Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis was done with R (R Core Team 2022, Vienna, Austria). Patient characteristics were described using mean, standard deviation (SD), Median and interquartile-Range (IQR).

Fisher`s Exact Test was used to determine differences between suspected diagnoses and the results of qSOFA-scoring. Frequencies of suspected diagnoses and referring healthcare providers were described using total numbers and percentages. Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment was described using Median and IQR. Differences between groups were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

Of 362 patients that were diagnosed with sepsis during their hospital stay, 277 had a severe infection (possible sepsis) or confirmed sepsis at the time they were admitted to hospital by the emergency department and were included for further analysis. Of those 277 patients, 161 had a severe infection and 116 were diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency department.

Gender distribution was not equal with 120 female (43.3%) and 157 male (56.7%) participants. 70 female participants and 91 male participants were diagnosed with a severe infection. 50 female and 66 male participants were diagnosed with sepsis.

The mean ages were similar in patients with severe infection, 70 years (SD 16.1, median 73.0, IQR 20.00) and sepsis 74 years (SD 14.6, median 76.5, IQR 18.25).

Diagnoses in the Emergency Department at time of hospital admission:

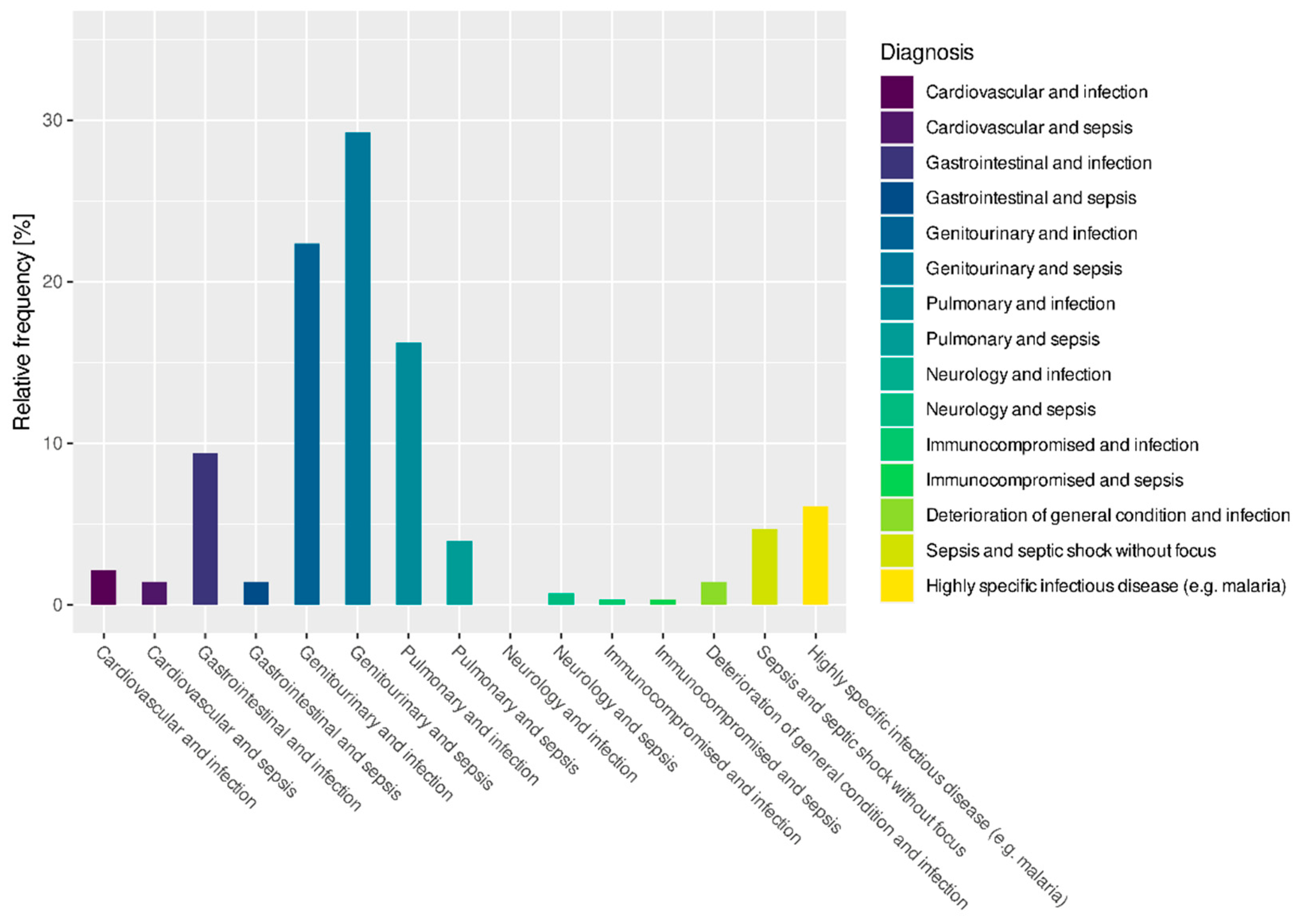

Figure 1 shows the frequency of diagnoses that were made in the emergency department at time of hospital admission.

Results of qSOFA scoring in the patient cohort

Because of missing values, we were only able to calculate the qSOFA in 103 out of 161 patients (64.0%) that were diagnosed with a severe infection and 80 out of 116 patients (69.0%) that were diagnosed with sepsis. Of the 161 patients with a severe infection 35/103 (34.0%) had a qSOFA of 0, 35/103 (34.0%) had a qSOFA of 1, 30/103 (29.1%) had a qSOFA of 2 and 3/103 (2.9%) had a qSOFA of 3. Of the 116 patients that were diagnosed with sepsis 14/80 (17.5%) had a qSOFA of 0, 24/80 (30.0%) had a qSOFA of 1, 32/80 (40.0%) had a qSOFA of 2 and 10/80 (12.5%) had a qSOFA of 3. While the qSOFA scores of patients that were diagnosed with sepsis differed significantly from patients that were diagnosed with a severe infection (p = 0.007) and time to initiation of antibiotic treatment differed between qSOFA-Scores (p < 0.001), there was no significant difference in qSOFA scores between the different suspected diagnoses made by prehospital healthcare providers (p = 0.540).

Referring healthcare personnel:

The largest proportion of patients were presented to the emergency department by EMS (106/277, 38.3%). Prehospital emergency physicians presented 80/277 patients (28.9%), while 36/277 patients (13.0%) were referred by their general practitioner. 39/277 patients (14.1%) presented themselves and in 16/277 patients (5.8%) it was not recorded whether the patient was referred by a healthcare provider.

Suspected diagnoses at time of presentation:

An infection was suspected in 124/277 (44.8%) patients and sepsis was suspected in 31/277 (11.2%) patients by the referring healthcare provider. 122/277 patients (44.0%) were presented to the emergency department with other suspected diagnoses.

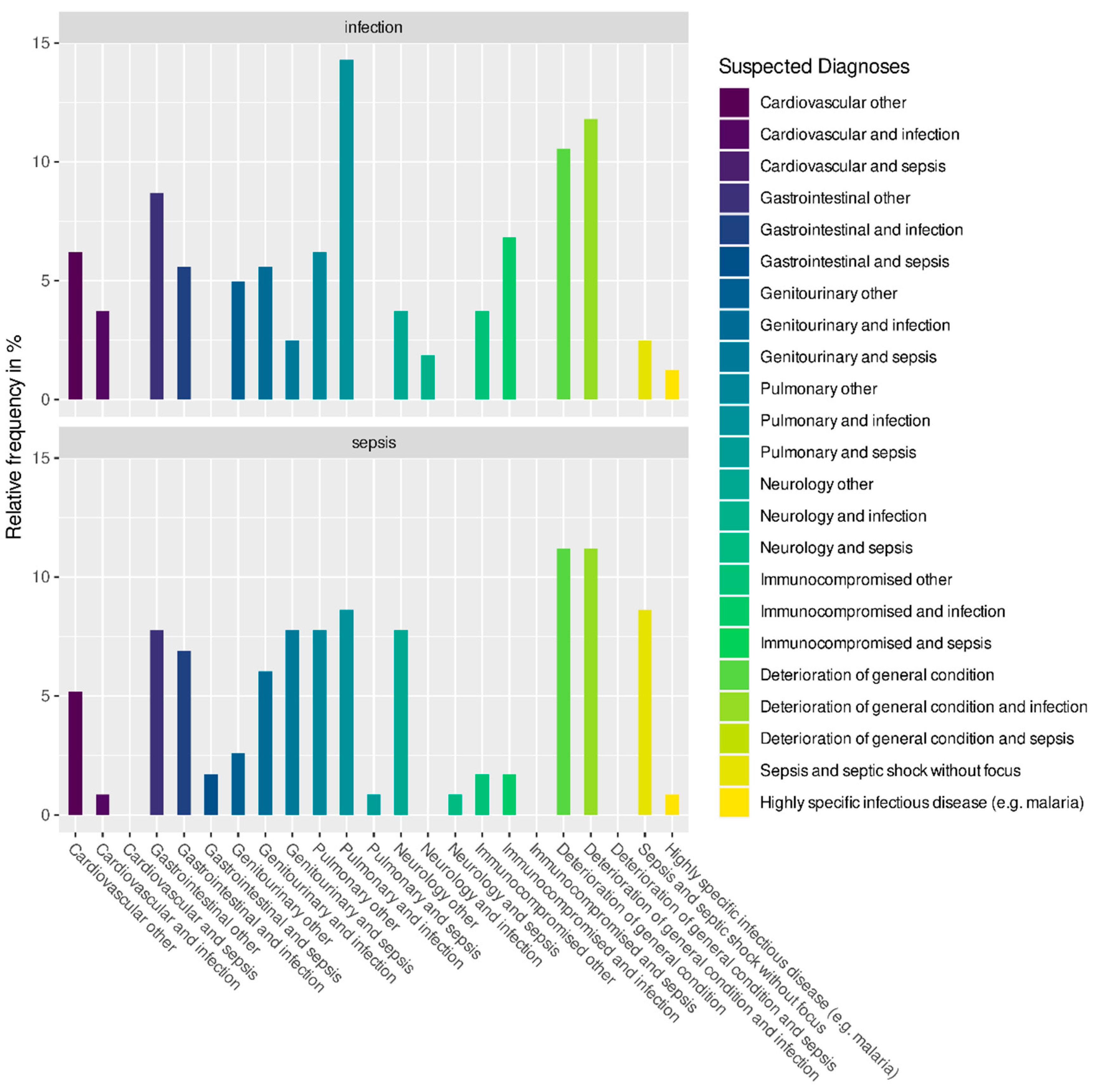

Figure 2 shows the suspected diagnoses in detail for patients that were diagnosed with sepsis or severe infection in the emergency department.

Frequency of suspected sepsis or infection by different referring healthcare providers

Table 1 demonstrates the suspected diagnoses organized by type of referring provider.

Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in patients diagnosed with a severe infection

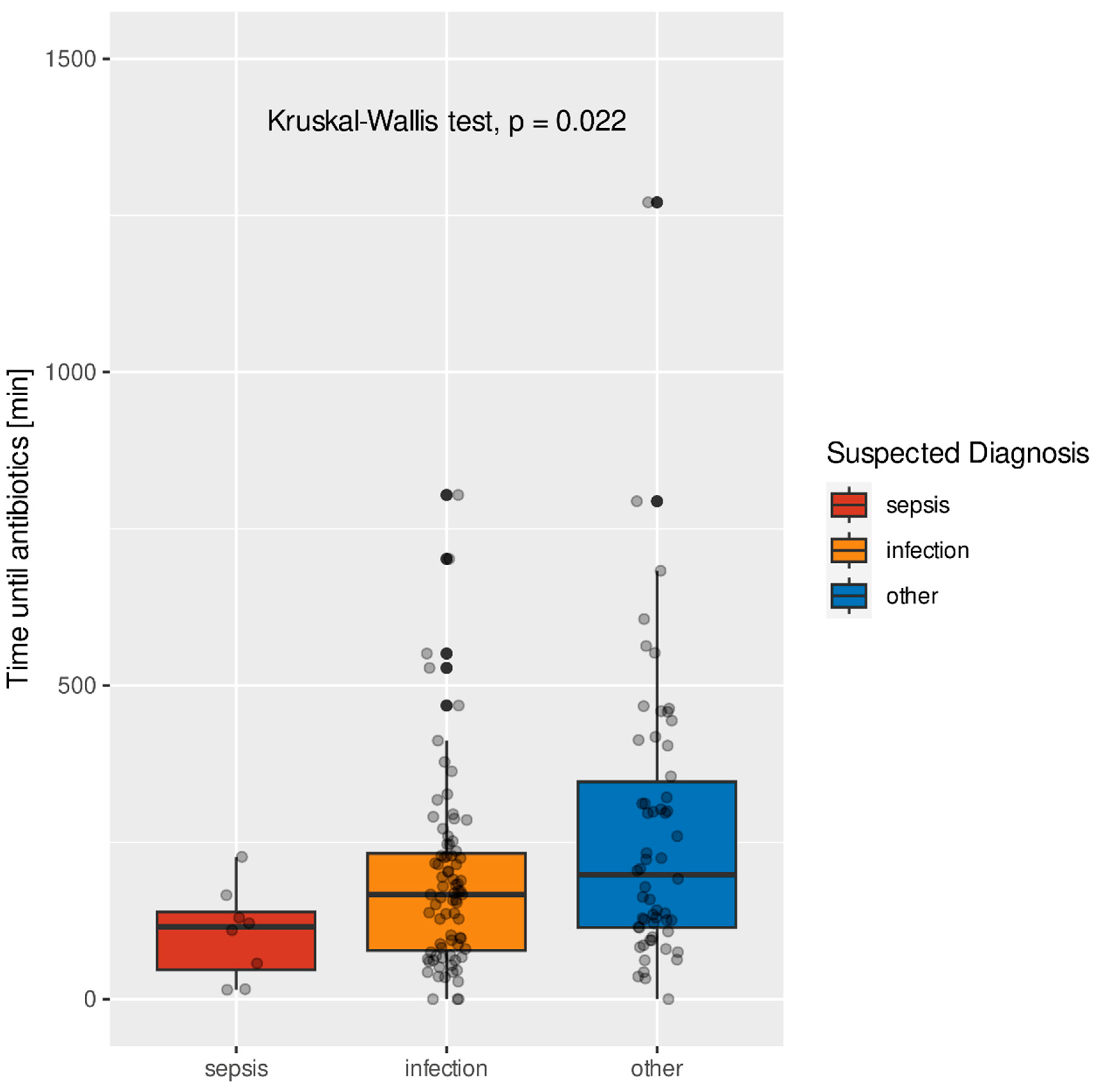

Figure 3 shows the time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in patients that were diagnosed with a severe infection in the emergency department and the suspected diagnoses at time of presentation to the emergency department.

The median times were 115.5 minutes (IQR 92.25) for suspected sepsis, 167 minutes (IQR 155.00) for patients with suspected infection, and 198.5 minutes (IQR 232.50) for other suspected diagnoses. The differences between these groups were significant (p = 0.022).

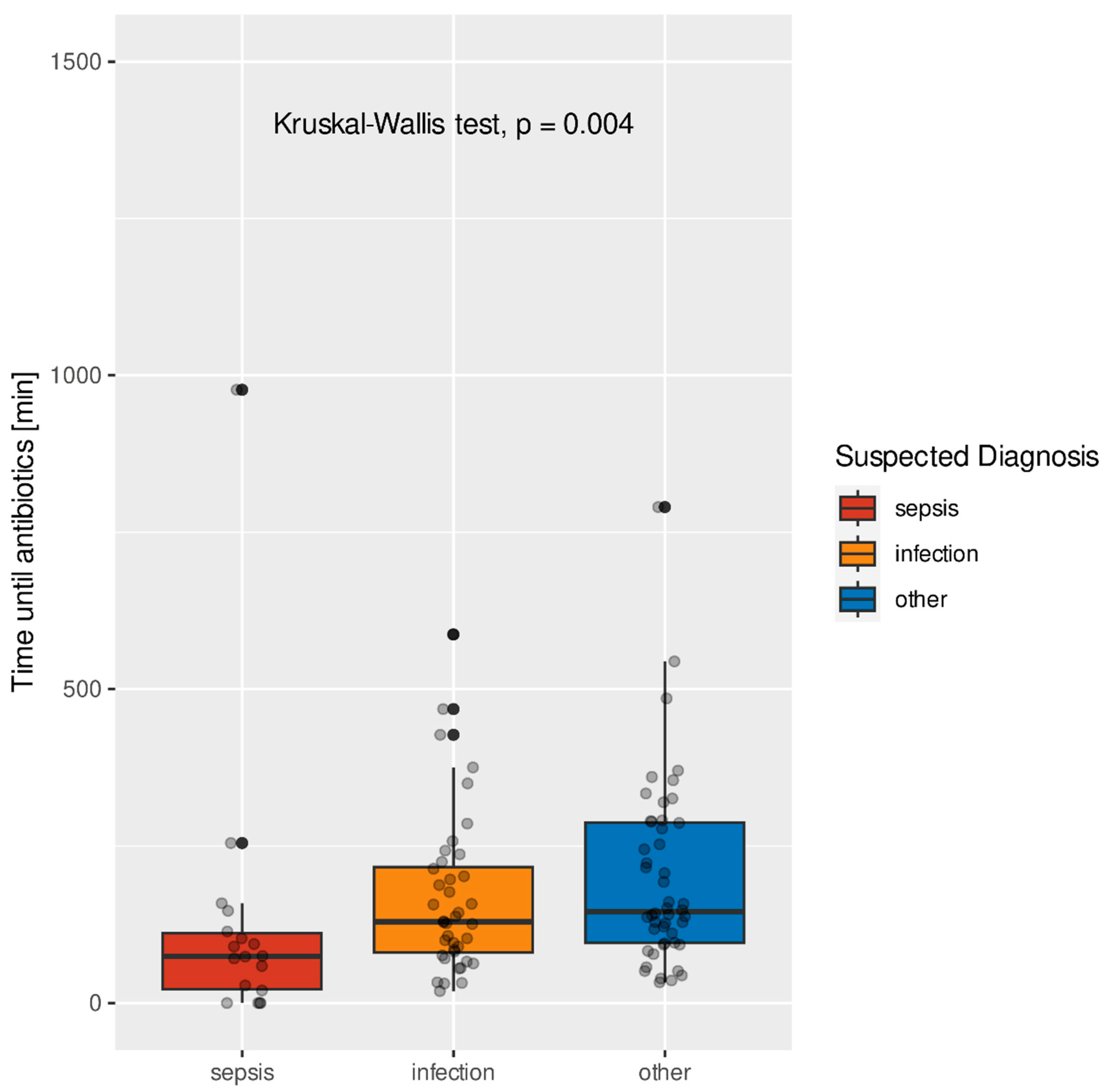

Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in patients diagnosed with sepsis

Figure 4 shows the time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in patients that were diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency department and their suspected diagnoses at the time of presentation.

The median times were 74.5 minutes (IQR 89.25) for suspected sepsis, 129.5 minutes (IQR 136.25) for patients with suspected infection, and 145.5 minutes (IQR 191.75) for other suspected diagnoses. The differences between the groups were significant (p = 0.004).

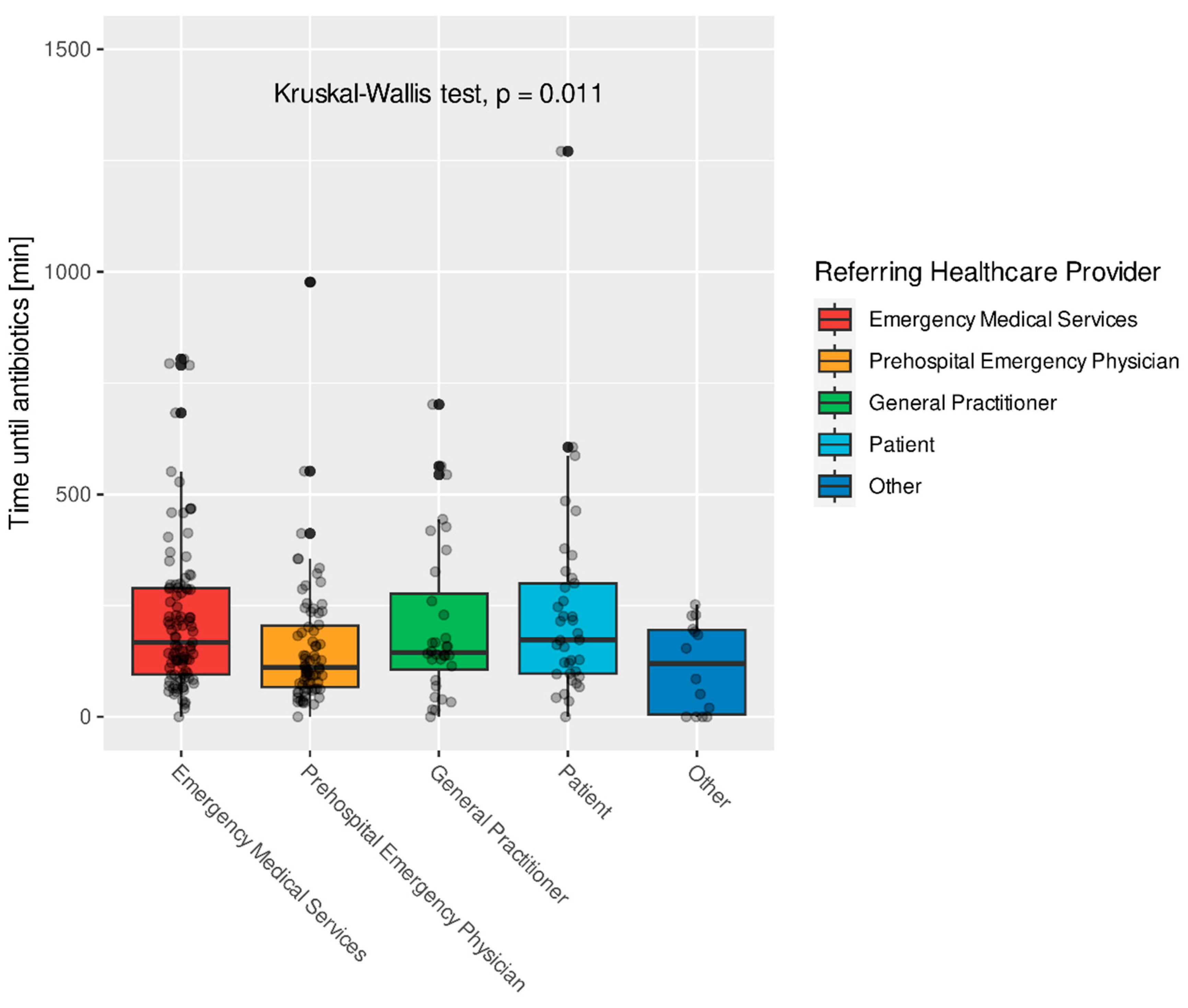

Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment stratified by referring healthcare providers

Figure 5 shows the time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in minutes in patients with severe infections or sepsis and which healthcare provider referred or presented the patient to the emergency department.

The median times were 148.0 minutes (IQR 183.00) for patients presented by EMS, 100.0 minutes (IQR 136.00) for patients presented by a prehospital Emergency Physician, 139.0 minutes (IQR 89.00) for patients referred by their general practitioner, 139.5 minutes (IQR 167.75) for self-presenters and 10.0 minutes (68.75) in patients where no healthcare provider was recorded. Differences between the different referring healthcare providers were significant (p=0.011).

Discussion:

Rapid recognition and early treatment are the mainstays of sepsis therapy [

1]. However, as there is no gold standard test for sepsis and laboratory tests are usually not available in the prehospital setting, making the diagnosis can be challenging. In our study most patients with sepsis or severe infections were presented to the Emergency Department by EMS. But of 106 patients with sepsis or severe infection brought in by EMS, sepsis was only suspected in 4 patients (3.8%) and an infection was only suspected in 49 patients (46.2%). In 53 patients (43.4%) later diagnosed with sepsis or a severe infection, this was not recognized at the time of presentation. Prehospital Emergency Physicians performed better, suspecting the diagnoses sepsis in 16 of 80 patients (20%). This may be attributable to a higher level of awareness due to treating these patients more regularly in the hospital setting. On the other hand, Prehospital Emergency Physicians are usually deployed to care for sicker patients and therefore might be biased towards making these diagnoses more often. Self-presenters did not suspect sepsis in any case but had the highest suspicion for an infection (26 of 39 patients, 66.6%). This finding is not surprising given that “sepsis” is largely a medical term with which most lay people would not be familiar. It should be noted that of the 277 patients diagnosed with severe infection or sepsis, only 31 patients (11.2%) presented with suspected sepsis and only 124 patients (44.8%) were suspected to have an infection. In 122 patients (44%) later diagnosed with severe infection or sepsis, this was not recognized by prehospital personnel.

In recent years, efforts have been made to raise awareness of sepsis in the prehospital field, but its recognition continues to lag. Current guidelines for management of sepsis and infection do not adequately take prehospital care into account - though early treatment must of course begin with early recognition, and early recognition begins in the prehospital setting. In this study, time to antibiotic treatment differed significantly depending on the diagnoses that were suspected at time of presentation to the emergency department in both septic patients (p=0.004) and patients with severe infections (p=0.022) and between the different referring healthcare providers (p=0.011).

Patients that were diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency department and in whom sepsis was suspected at time of presentation received antibiotic treatment in 74.5 (IQR 89.25) minutes, while patients with severe infections and suspected sepsis received treatment in 115.5 (IQR 92.25) minutes. Patients that were diagnosed with a severe infection in the emergency department and in whom sepsis was suspected at time of presentation received treatment after 129.5 (IQR 136.25) minutes, while patients with suspected infection received treatment after 167 (IQR 155.00) minutes. These findings stand in stark contrast to those in septic patients where neither sepsis nor infection was suspected, who experienced a time to antibiotic treatment of 145.5 minutes (IQR 191.75), as well as patients with a severe infection where neither sepsis nor infection was suspected, who experienced a time to antibiotic treatment of 198.5 minutes (IQR 232.50).

In this study, we identified statistically significant differences between initiation of antibiotic therapy based on referring healthcare provider. Patients that were presented by prehospital Emergency Physicians received treatment within 100.0 minutes (IQR 136.00), patients that were referred by their general practitioner received treatment within 139.0 minutes (IQR 89.00), self-presenters received treatment within 139.5 minutes (IQR 167.75), while patients presented by EMS received antibiotics after 148.0 minutes (IQR 183.00). Though we are unable to draw firm conclusions from this data, due to uncontrolled confounders like bias in deployments, our findings do suggest that further investigation is warranted into the different providers who manage sepsis in the prehospital setting.

Our data shows that early recognition of sepsis or severe infection by the referring healthcare providers is associated with shorter time to effective treatment in hospital. This might in part reflect that sepsis or severe infection is earlier recognized in sicker patients, as patients that were diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency department received antibiotics earlier than patients with severe infections. However, our data shows that in septic patients, as well as in patients with severe infections the time until antibiotics were administered differed significantly depending on the suspected diagnoses, while qSOFA-scores did not differ significantly between the different suspected diagnoses (p = 0.540).

These findings have significant implications with regards to patient assessment in the prehospital field as well as in the emergency department. To make the diagnosis, it is critical to have a high suspicion of the illness and to use appropriate screening tools routinely. Several screening tools are available, but the diagnostic accuracy of these tests is variable, with most either having a low sensitivity and/or poor prognostic value like the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria [5, 6]. Furthermore, as most scoring tools require laboratory values, they may not be useful for out-of-hospital care. In 2016 the qSOFA score was introduced [

4], as a better prognostic tool for associated mortality [

7]. Unfortunately, the qSOFA score has a low sensitivity, and is therefore not useful as a screening tool [

8]. That said, the score is still widely used by clinicians for this purpose, with many of them unaware of its limitations. One reason might be that the score is easy to remember and convenient to calculate from parameters that are collected routinely during patient assessment with no laboratory values needed. The updated surviving-sepsis campaign 2021 guidelines strongly recommend against the use of qSOFA as a single tool for identification of sepsis, but other scores like the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) are more complicated to calculate, though they are more sensitive for detecting critically ill patients [8, 9]. However, despite these limitations, the use of scoring systems has shown to be superior to clinical judgement alone [

10]. Therefore, efforts should be made to identify a score that is sensitive enough, hence practical for use in the pre-hospital setting. Alternatively, as tablet computers are increasingly used by EMS agencies for electronic patient care reporting, these could be programmed to calculate scores automatically from the patients’ vital signs when entered into the electronic patient care reporting system.

In the emergency department, it may be possible to calculate these scores during triage, as many hospital systems take the patients’ vital signs at this time. An automated calculation could also potentially be employed in this setting, as many hospitals have established electronic patient records and vital signs are often automatically transferred, thus not prolonging the triage process. That said, predictive scoring results in many scenarios are only one piece of the clinical puzzle – carrying with them the potential to harm patients if algorithms are followed blindly and the individual patient and circumstances are not considered [11, 12].

Limitations:

The study retrospectively evaluates suspected diagnoses, type of referring healthcare provider and time to initiation of antibiotic treatment in patients that were diagnosed with sepsis and severe infection in the emergency department in one university hospital. Therefore, the findings of this study might be of limited value for other populations, as training of different healthcare providers might differ between different services and across borders. Our study is also subject to the usual biases and limitations associated with a retrospective design.

We only evaluated patients that were diagnosed with severe infection or sepsis. Therefore, we were not able to evaluate how often patients are presented to the Emergency Department with suspected sepsis or severe infection and were diagnosed with other illnesses.

Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment was extracted from the electronic healthcare record of the Emergency Department from the time of administrative admission of the casefile in the Emergency Department to the time when the care taking emergency physician prescribed antibiotics via the electronic Emergency Department Management Program. The true time to initiation of antibiotic treatment might differ from the point in time when the treatment was documented in the healthcare record. This may be particularly relevant in critically ill patients where treatment begins immediately and documentation often follows later.

Conclusions:

Early recognition of sepsis in the pre-hospital setting needs to be improved. Our study demonstrates that pre-hospital recognition has the potential to shorten time to antibiotic treatment upon arrival to the hospital, and this may translate to meaningful improvements in patient outcomes. Appropriate scoring systems need to be used routinely in patient assessment to aid effective pre-hospital recognition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S6:

Figure 1. Frequency of diagnoses in the emergency department at time of hospital admission (%). Figure S8:

Figure 2. Suspected diagnoses made by prehospital healthcare providers for patients that were diagnosed with sepsis or severe infection in the emergency department (%). Table S9:

Table 1. Suspected diagnoses organized by referring healthcare provider (total number and %). Figure S10:

Figure 3. Time to initiation of antibiotic, in minutes, in patients with severe infection and the suspected diagnoses of their prehospital healthcare personnel. Figure S11:

Figure 4. Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment, in minutes, in patients with sepsis and the suspected diagnoses of their prehospital healthcare personnel. Figure S12:

Figure 5. Time to initiation of antibiotic treatment, in minutes, in patients with severe infection or sepsis and their referring/presenting healthcare provider.

Author Contributions

MB: CK and JR conceived the study, designed the trial and obtained ethical approval. MB and NF collected the data. MK and WS provided statistical advice and analyzed the data. MB, NF and ADS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. MB takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The authors did not receive any funding and declare that they have no competing interests.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen on 16/09/2020 with the study number 20-9550-BO and had been preregistered in the German Clinical Trials Register on 26/02/2021 under DRKS00022986. The study was carried out in accordance with all relevant regulations and as described by the study protocol.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not deemed necessary by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Møller MH, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Nov;47(11):1181-1247. Epub 2021 Oct 2. PMID: 34599691; PMCID: PMC8486643. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, Suppes R, Feinstein D, Zanotti S, Taiberg L, Gurka D, Kumar A, Cheang M. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006 Jun;34(6):1589-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, Osborn TM, Townsend S, Dellinger RP, Artigas A, Schorr C, Levy MM. Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: results from a guideline-based performance improvement program. Crit Care Med. 2014 Aug;42(8):1749-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10. PMID: 26903338; PMCID: PMC4968574. [CrossRef]

- Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and Prognostic Value of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome and Organ Dysfunctions in Ward Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Oct 15;192(8):958-64. PMID: 26158402; PMCID: PMC4642209. [CrossRef]

- Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 23;372(17):1629-38. Epub 2015 Mar 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, Sprung CL, Colardyn F, Blecher S. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on "sepsis-related problems" of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998 Nov;26(11):1793-800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman OA, Usman AA, Ward MA. Comparison of SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS for the early identification of sepsis in the Emergency Department. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;37(8):1490-1497. Epub 2018 Nov 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattanasit P, Khwannimit B. Comparison the accuracy of early warning scores with qSOFA and SIRS for predicting sepsis in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Aug;46:284-288. Epub 2020 Aug 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton JN, Price CL, Silvey NE, Brace SJ, Perkins GD. Is the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) superior to clinician judgement in detecting critical illness in the pre-hospital environment? Resuscitation. 2012 May;83(5):557-62. Epub 2012 Jan 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton NR, Gurm HS. Door to Balloon Time: Is There a Point That Is Too Short? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 Nov-Dec;58(3):230-40. Epub 2015 Sep 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortoleva JP, Cordes CL, Salehi P, Shapeton AD. Predictive Scoring: Should It Tell Us the Odds? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021 Dec;35(12):3708-3710. Epub 2021 Sep 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).