1. Introduction

The metal coating process is based on the need to protect metal parts and structures from damage caused by operating conditions. Metals are used for structural components, mechanisms, enclosures, etc. including steel, stainless steel, aluminum and titanium. These metals will increase wear resistance and provide salvage for some components.

Laser surface treatment is an alternative to more conventional metal-based composite (MMC) manufacturing methods. In laser surface alloying, the powder mixture with a thin surface layer of the substrate is melted by a scanning laser beam. This leads to rapid solidification and surface layer formation [

2]. The rapid cooling and solidification of the molten group produced by the laser can lead to the formation of various unbalanced phases and the fine-tuning of the microstructure. If the powder is injected into a molten solution containing non-melting particles, an MMC surface will form on the surface of the substrate [

1].

The laser-treated hard coating has a lower surface energy than the reference, possibly due to the formation of hydrophobic carbide phases mainly on the surface of the sample, which also contributes to the improved anti-corrosion for this type of coating. It should be noted that the samples are not significantly oxidized during laser treatment, otherwise the surface energy would increase significantly [

8]. Oxidation is often associated with the formation of poorly adhered phases, which flake or delamination under very severe abrasive conditions. Although the surface energy decreases with increasing laser power, the fraction of polarizing components increases, contributing to better compatibility of the coating's surface with a wide range of oil-based or oil-based paints and primers., as can be seen on the envelope wetting process of the research papers [

9].

Surface treatments performed by laser irradiation include laser hardening, laser alloying and laser coating [

3,

4]. The common feature of all these processes is to generate certain thermal cycles in small, very localized areas of the part's surface, which then acquire new properties that allow it to resist wear, fatigue, and fatigue. and better corrosion while retaining most of its other original properties [

5].

Recent reviews of the principles and applications of laser processing describe the use of lasers as a controlled heat source for hardening [

6]. The classical approach to modeling the heat flow caused by a dispersed heat source traveling over the surface of a semi-infinite solid begins with the solution of a point source and integrates it on the beam surface. This widely used method requires numerical procedures to evaluate it, like the finite difference solutions of Shuja et al. [

7]. They developed a 3D model of heat flow and different beam power and travel speeds to determine the dimensional analysis of heat flow during heat treatment and melting. But the result is not easily distinguishable from complex shapes and requires complex calculations. Several authors have used the finite element method for numerical evaluation, as well as the FEM analyzes of W.

Typically, the hard surface microstructure is refined by additional heat treatment for the purpose of stress relief or subsequent formation of hard phases (carbide, boride). Laser surface heat treatment is commonly used to treat carbon steel and alloy steel components, due to its better directivity and time efficiency in reaching and maintaining the desired temperature.

By adjusting the hardness and wear resistance of the surface, an improvement in the fatigue resistance and corrosion resistance of hard coatings can be achieved [

12,

13]. The improvement in hardness due to laser heat treatment can be attributed to the microstructural growth of austenite in Fe-C containing systems, which is annealed in situ to martensite due to high temperature gradient [

15], avoiding the use of use any liquid or gas. soak the media. Then, laser heat treatment can promote the formation of carbides or borides in the microstructure of the material, which positively contributes to the increase in hardness and wear resistance. According to ISO-ASTM 52900 (2015), AM is a process of joining materials, layer by layer, to create three-dimensional parts [

21]. In recent years, AM applications have been expanded into several industry sectors as technology offers opportunities to improve functionality, productivity and competitiveness. Metallic AM has limitless potential and has recently been explored in the medical, aerospace and automotive industries [

22]. On the one hand, products with complex shapes, flexibility in operation and reduced production time can be produced using the AM method. However, they face several challenges:

poor surface condition, undesirable microstructural phases, porosity and defects, delamination, signs of wear, lack of hardness and corrosion resistance and reduced service life. The objective of this paper is to correlate the microstructures and mechanical properties of metal coatings after laser heat treatment.

This paper aims to extend our previous studies on laser treatment of some metallic materials, by providing more detailed information on the effect of laser energy on the surface properties of the layer. open-arc deposition hard coating. In this regard, the variation of the micro hardness and wear resistance of the surface is presented.

2. Research methods

The ability to control and manipulate friction is important for many applications. From a practical point of view, it is desirable to be able to control the friction force so that the total frictional force is reduced (or improved), the turbulent mode is eliminated and a smooth slide is instead. Such control can be of great technological importance for micro-mechanical devices and computer drives, where the early stages of motion and stop often exhibit unexpected slip or failure. want. On the other hand, chaotic clubbing behavior may be desirable, e.g. g., in stringed instruments. Traditionally, control of friction has been approached by chemical means, usually by supplementing the base lubricant with friction modifiers. However, the standard lubrication techniques used for large objects are expected to be less effective in the micro and nano worlds. Therefore, new methods of control and manipulation are needed.

Metal coating was performed using a Luftarc 150 Ductil arc welding device, using four types of electrodes (

Table 1). Welding amperage 700 A, welding voltage 40 V, welding speed 40-45 mm/min. and the width of the weld bead is 10 mm. The base metal is S275JR SR EN 10025-2:

2004, 20mm thick. Coating is 5 mm thick for all samples. After coating, the samples were annealed at 600°C, to eliminate internal stress.

Experimental research was be focused on the influence of laser radiation on the structure and properties of welded loaded layers and their opportunities to improvement. This influence will be studied in two variants, as follows:

2.1. Hardening with laser beam

Thermal cycle of superficially hardening with laser beam is very sharp, what means that temperature in layers variation very quickly when heating and cooling, and the heat treatment is without of hold time.

Heating temperature for hardening is 0.6 – 0.7 x Tmetling. In short time of laser beam action, the structures of layers heated above AC3 is transformed into austenite having very fine granulation. Caused by the internal thermal stresses this austenite will be hardened and transformed into inhomogenous martensite with a large number of dislocations. Caused by the chemical anisotropy it is possible to keep a part of residual austenite. By these reasons, at superficial laser heat treatment it is possible to appear some internal stresses. That austenite is transforming in martensite with internal tension and residual austenite. To avoid the apparition of cracks is very important to respect the optimal parameters. In case of steel with high carbon content and alloyed steel that danger is high and is necessary to set the parameters very carefully.

2.2. Surface melting with laser beam

In case of surface melting a very thin surface layer is melted and after stop of laser beam solidification of melted layer is very quickly.

In case of heating with laser beam for surface melting, a big part of energy is lost by reflection. To increase the energetically efficiency is necessary to apply on sample surface a film of absorbing materials of 30μm thickness.

3. Results and discussion

Laser heat treatment is applied to four types of welding coatings, presented in

Table 1. Laser heat treated samples in nine variants, with Nd laser source:

YAG - Rofin DY 570 Germany, made by robot ABB - Sweden.

Table 2 shows the intensity of the laser beam during the surface heat treatment, which is chosen to apply to many laser heat treatments.

The YAG crystal features very good optical and mechanic, with a very low laser effect limit, an increased thermal conductibility and is able to function at a temperature of 20-25°C in continuous or pulsating conditions continuous with a high repeating frequency. The YAG crystals are known from a solution of melted salts, in a closed platinum pot kept at a temperature of 1150°C for 24 hours and then cooled down to 750-850 °C with a rate of 4,3 °C per hour. The salt mixture composition is 3,4 mol % Y2O3, 7 mol % Al2O3, 4,15 mol % PbO and 48,1 % PbF2.

The thermal properties of the YAG crystal pure and impurified neodymium with neodymium are detailed in table 2 for three temperature values.

The fluorescence transitions that may lead to laser emission are the ones that correspond to the transitions

4F

3/2 →

4 I

9/2,

4F

3/2 →

4I

11/2 and

4I

3/2 →

4I

13/2. Their wave lengths is approx. 0,9 μm, 1,06 μm and 1,35 μm respectively.[

6]

The specific transition of the laser emission is located in a close infrared with a λ = 1,06 μm wave length. The width of this fluorescence line is bigger than 30 A. It may be noticed that the Nd: YAG is a four-level laser whose advantage is the achievement of a high amplifying coefficient. Also, given the fluctuation threshold, the Nd: YAG laser may function in a continuous condition with the aid of plain water circulation-based cooling.

An intense radiation of white light populates all levels located above 4F3/2, from where the ions turn bask towards it through non-radiating transitions. The 4I11/2 inferior level is located at 2x103 cm-1 above the fundamental level 4I9/2 and is void at room temperature, fact that facilitates the achievement of the pumping threshold. In addition, the energy levels of the neodymium ion are less sensitive to the features of the imperfections of the crystalline network because they are involved in the changes of the electronic configuration of the internal layers, instead of the electrons of the din external ones as in the case of Cr3+. This insensitivity of the Nd3+ ion related to what is in its environment facilitates the choice of yttrium-aluminum granite as matrix as well as the insertion in an amorphous matrix such as glass, for instance.

The life span of the neodymium ion’s fluorescence depends both on the quantity and on the quality of the doping as well as on the composition of the host material.

The efficiency of the Nd: YAG laser is approx. 4%. It may emit in certain conditions powers of 5 KW, in continuous conditions for laboratory needs, usually acceding to powers of 20-100 W. The Nd: YAG laser may function in an open condition or in mode coupling condition. In pulsating condition, the average power of the Nd: YAG generators is approx. equal to the output power in continuous conditions. The efficiency of this type of laser may be increased if in the YAG crystal are also being introduced Cr3+ impurities that substitute the Al3+ion. In this case occurs a non-radiating energy transfer from a Cr3+ ion pumped on the 2E level to a Nd3+ ion that develops into the 4F3/2 state.

Usually, a Nd: YAG laser consists of a neodymium doped cylinder bar with a 5-20 mm diameter and a 50-250 mm length, representing the active optical environment. The bar heads are optically laboured and have reflecting layers that form the resonant cavity of the laser. The optical pumping may be performed with a coherent source by using the emission of another laser or with the aid of a "classic" lamp with continuous emission or impulses (flash) that emit light on a wide scale in all directions of the environment.

For the pumping of neodymium lasers xenon or krypton lamps are being employed. The krypton lamps are more efficient than xenon lamps for the pumping of the pumping of neodymium lasers because they have a more powerful emission in the 810 nm absorption area of the neodymium. When the pumping energy exceeds 10 J it is more efficient to use xenon lamps. The improvement of pumping efficiency is obtained through the use of alkaline additive lamps. For the flash-emitted radiation to produce light as efficient as possible in the active environment, the assembly is mounted in a cylindrical reflector with a single or double elliptic section so that the lamp(s) and the active environment to be located in one of the focal points.

The laser radiation has a series of unique properties, some of them with an extremely important role in the use of the laser beam for thermal treatments. The laser radiation is practically monochromatic, meaning that it has such a narrow spectrum range that it may be replaced by a certain wave length and frequency.

Consequently, the power spectrum density of the laser radiation exceeds by a few lengths the power density of radiation of other known electromagnetic energy sources with extremely wide spectrum ranges.

The basic features of the laser beam – polarizing, glowing, time distribution of the beam are grouped into the most characteristic for thermal treatments, namely the capacity to concentrate a large amount of energy in an extremely short time span, on a given surface, and in a small substance mass.

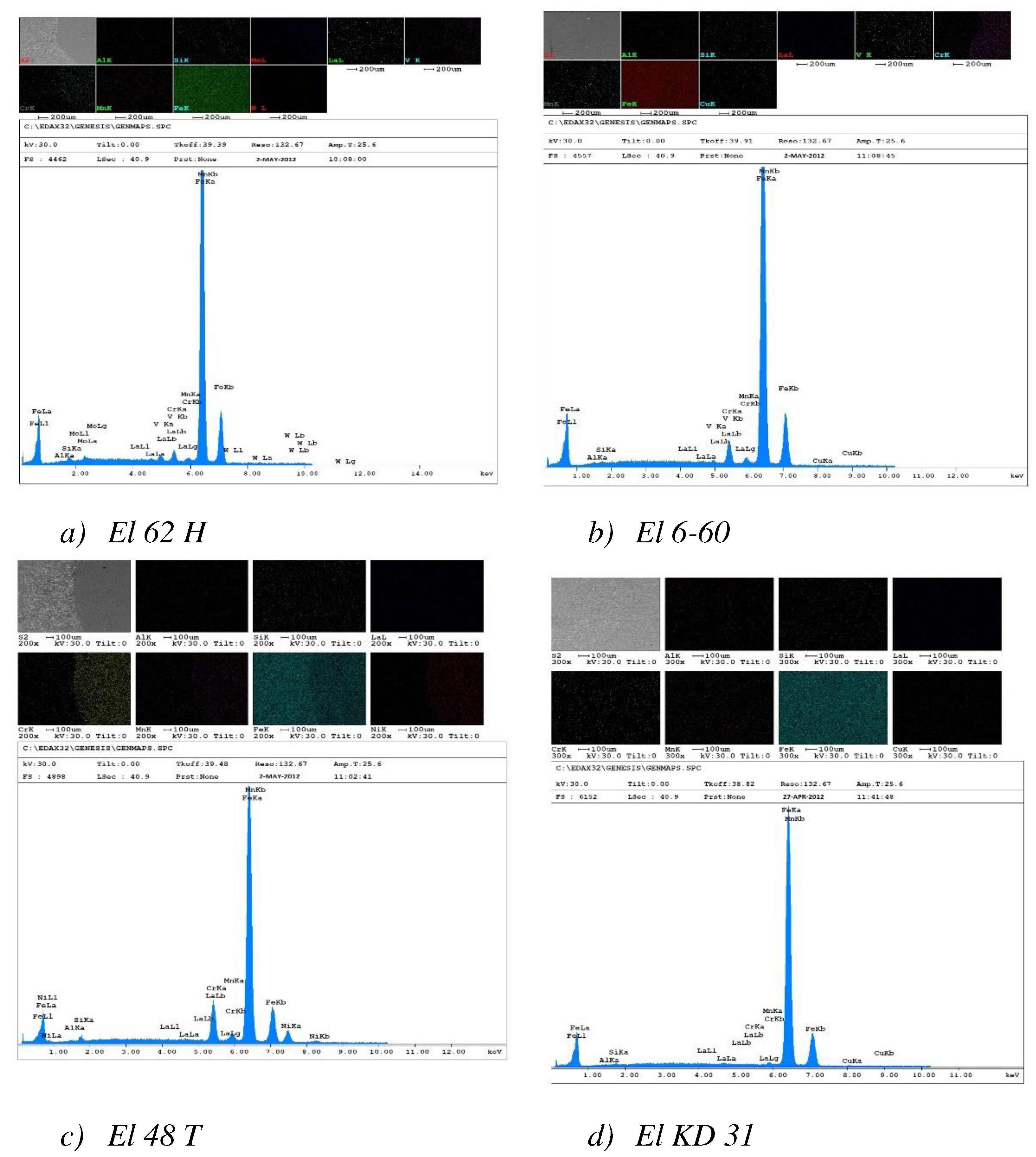

The obtained results were evaluated with PMT 3 micro-hardness tester, electronically microscope Nova Nano SEM and chemical analyzer EDAX Orbis Micro-XRF.

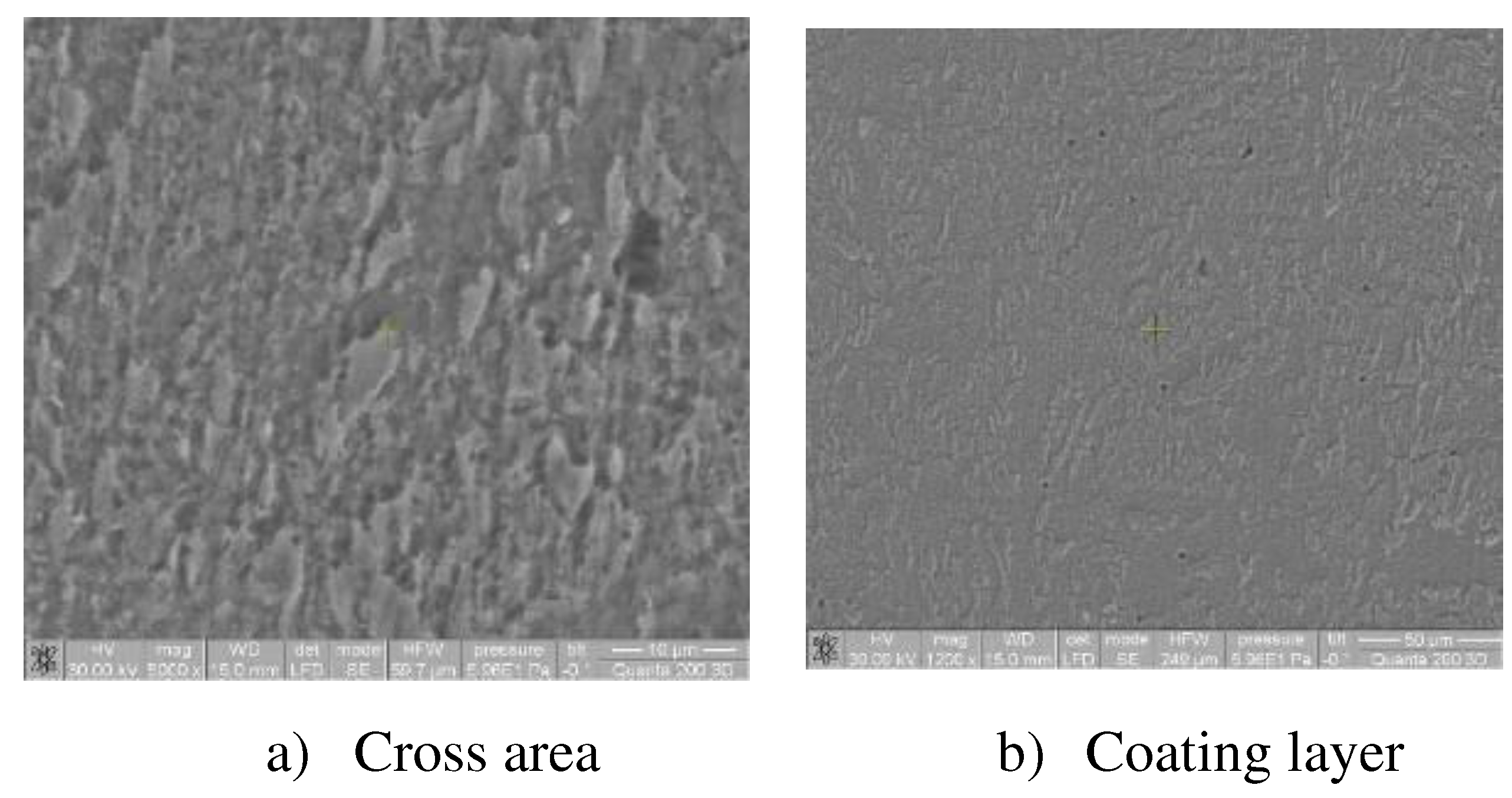

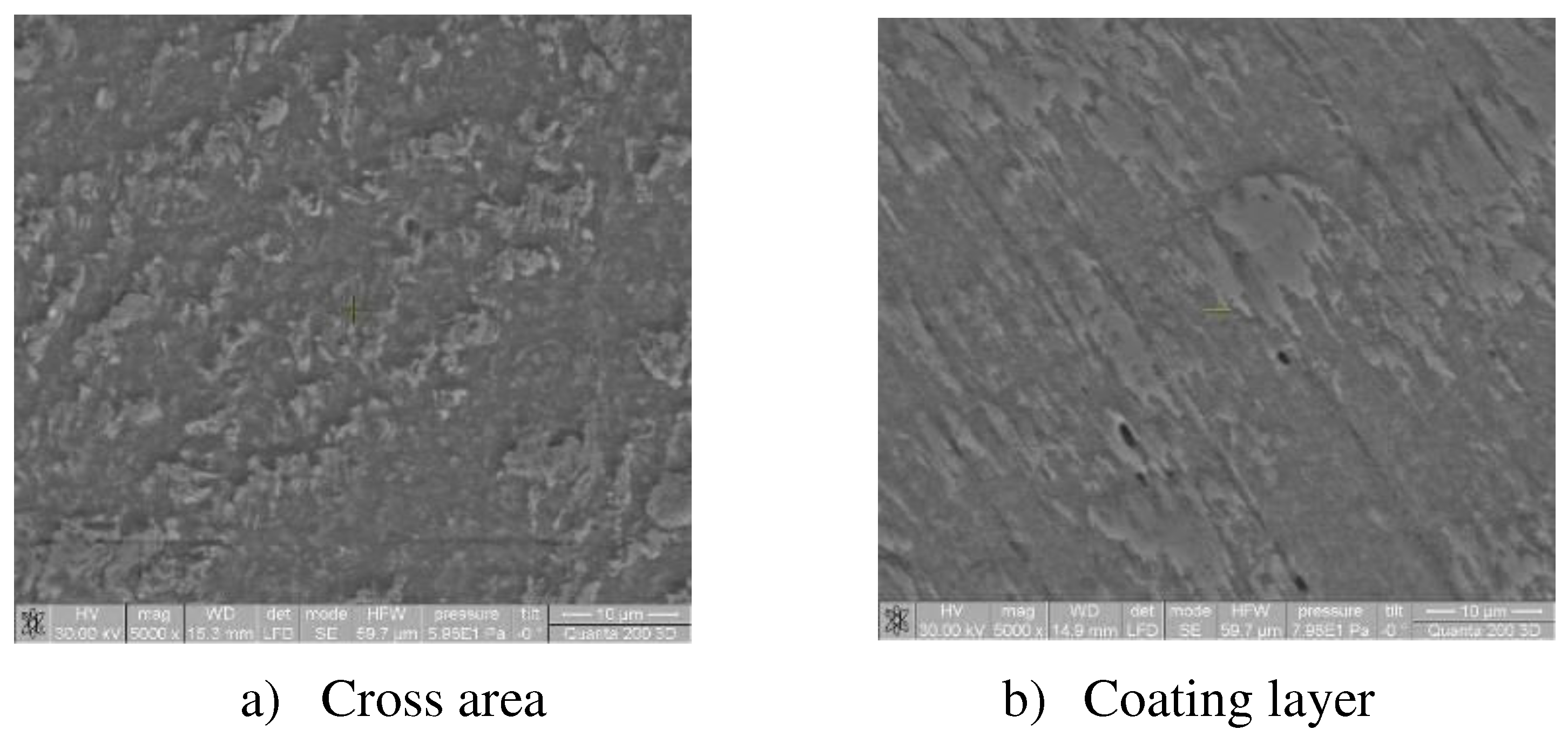

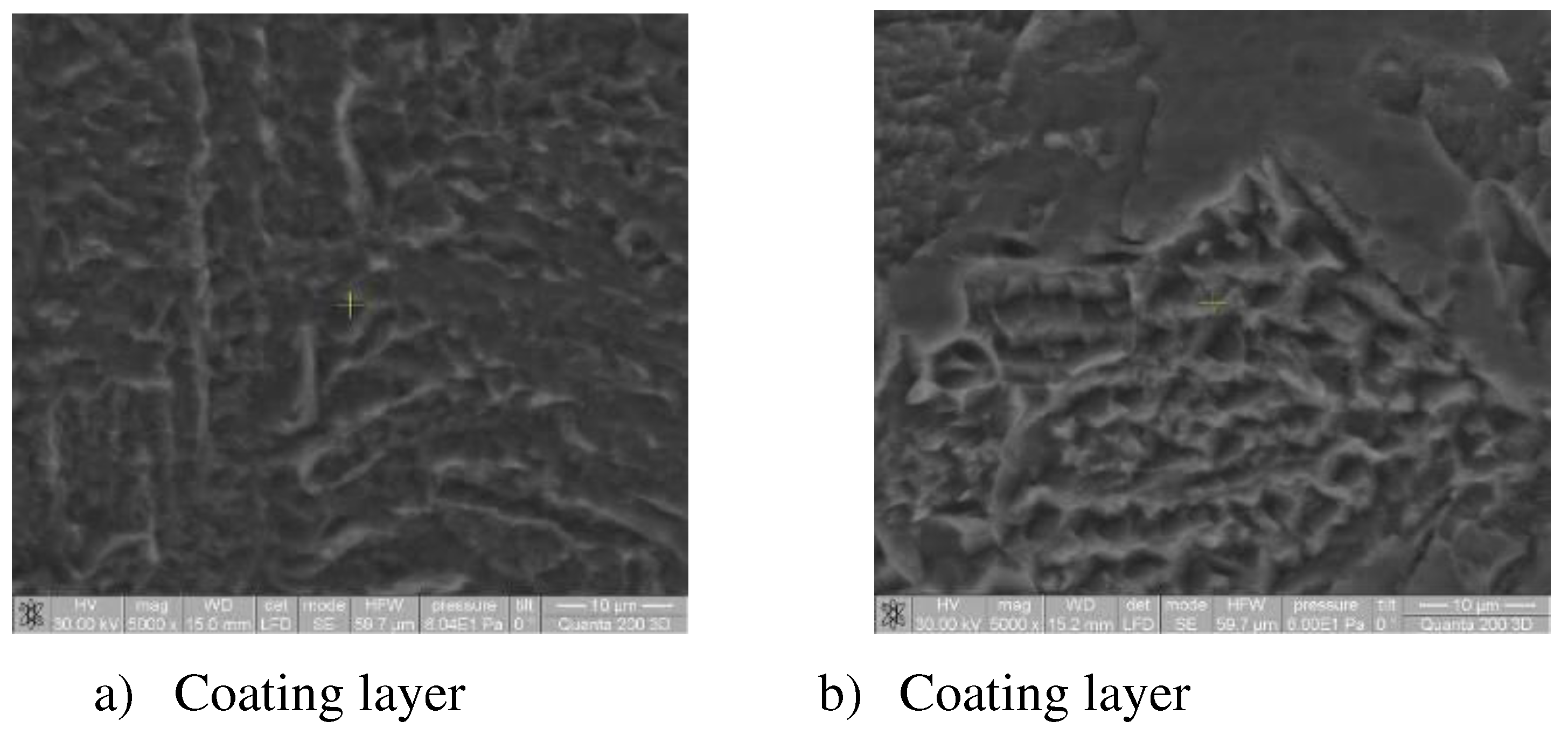

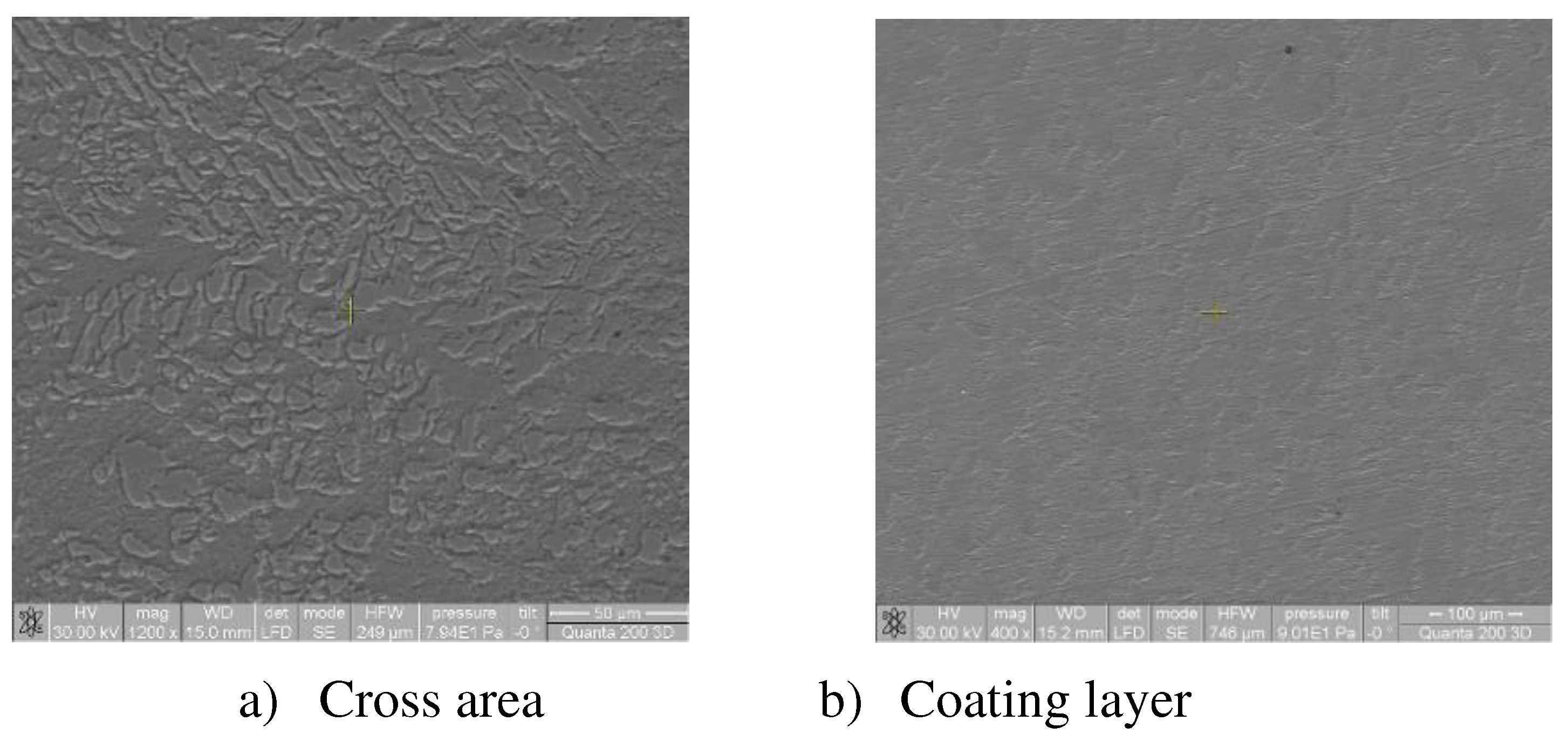

Laser treated layer thickness is between 0.2 – 0.9 mm, depends on intensity of laser beam. The structures obtained using SEM technique are presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

The increase in Cr concentration determines the formation of the chemical compound Cr3C2 in the ferrite-pearlite matrix, especially in the case of electrodes 6 - 60 and KD31. In the case of metal coatings with 48T electrode, which has a low Cr concentration, no chemical compound formation could be observed. In

Figure 5 is presented the chemical composition obtained with the EDAX. chemical analyzer

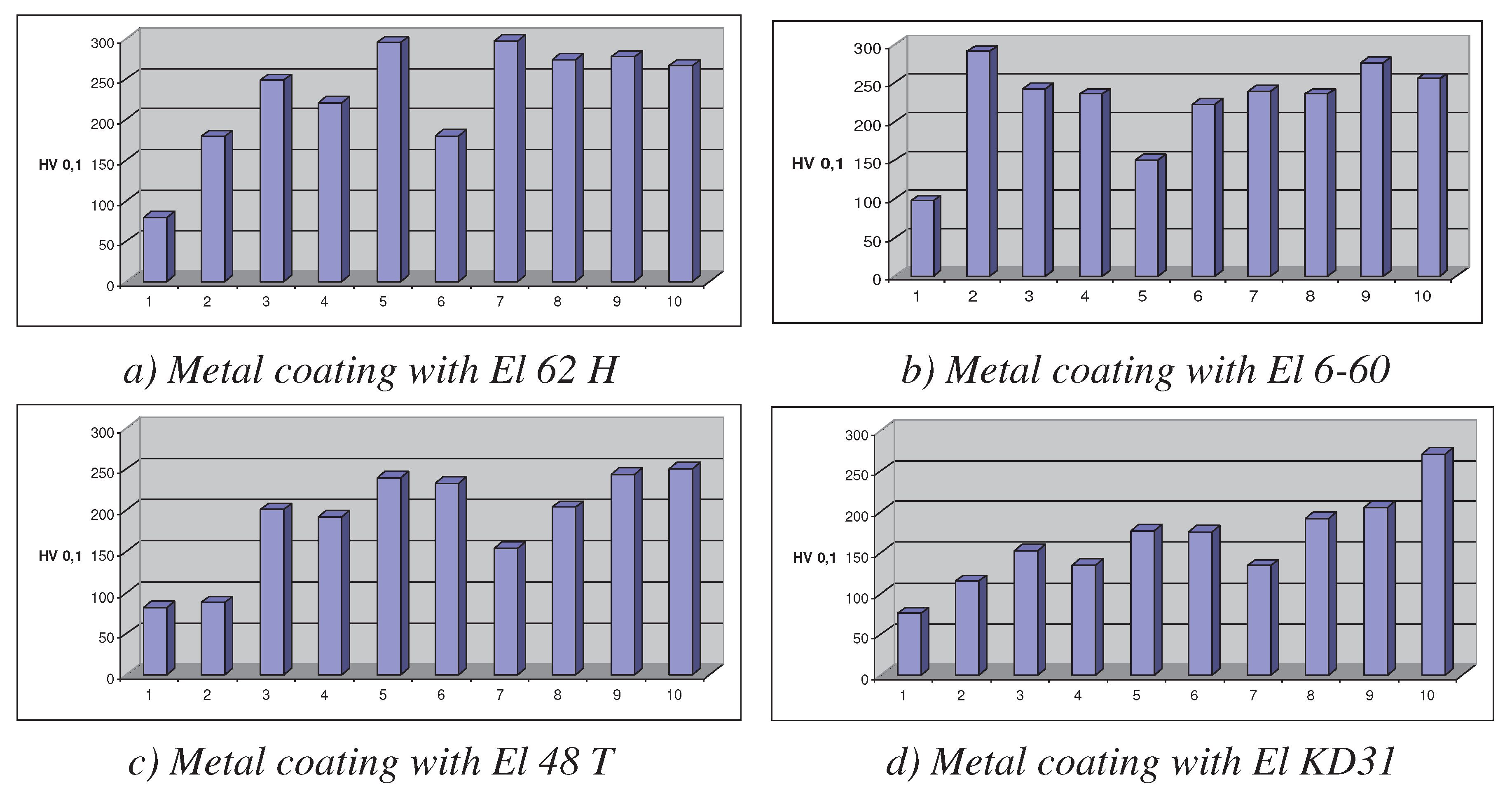

Evaluation of mechanical properties was made with micro hardness and wear resistance. The obtained microhardness is presented in

Figure 6

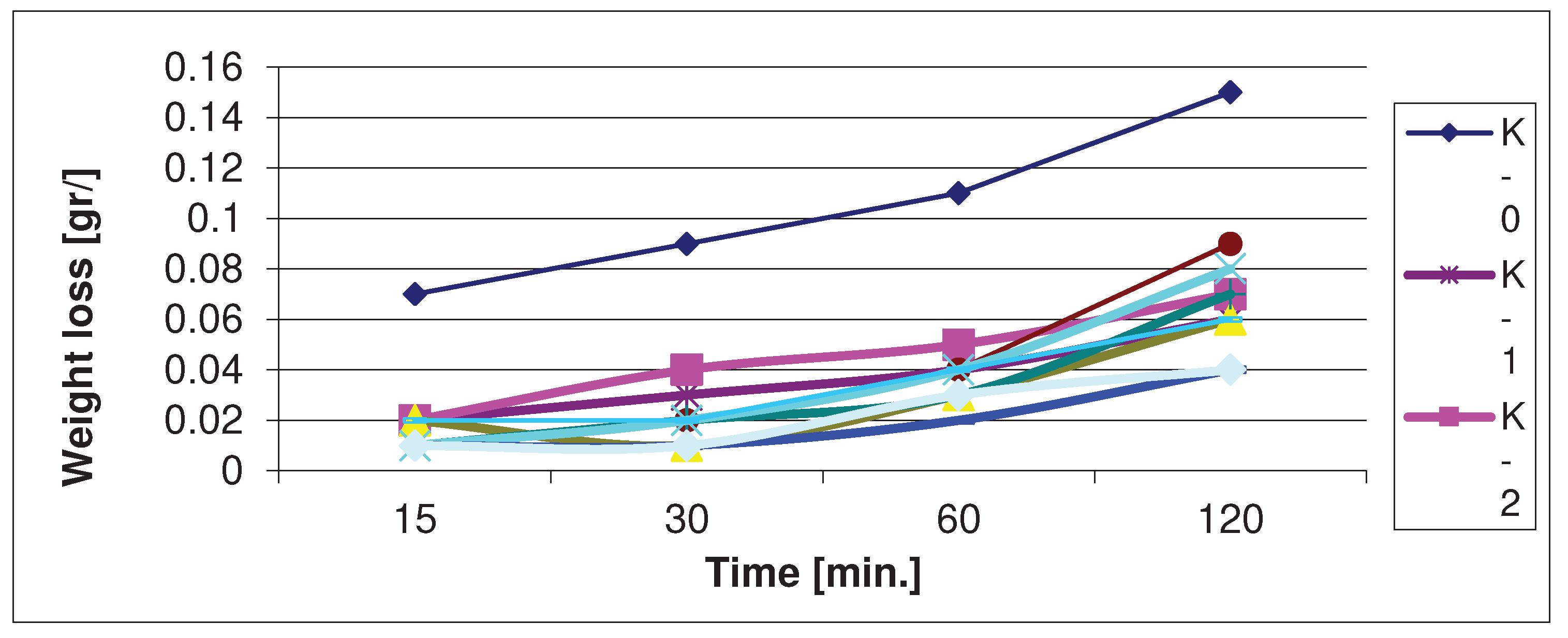

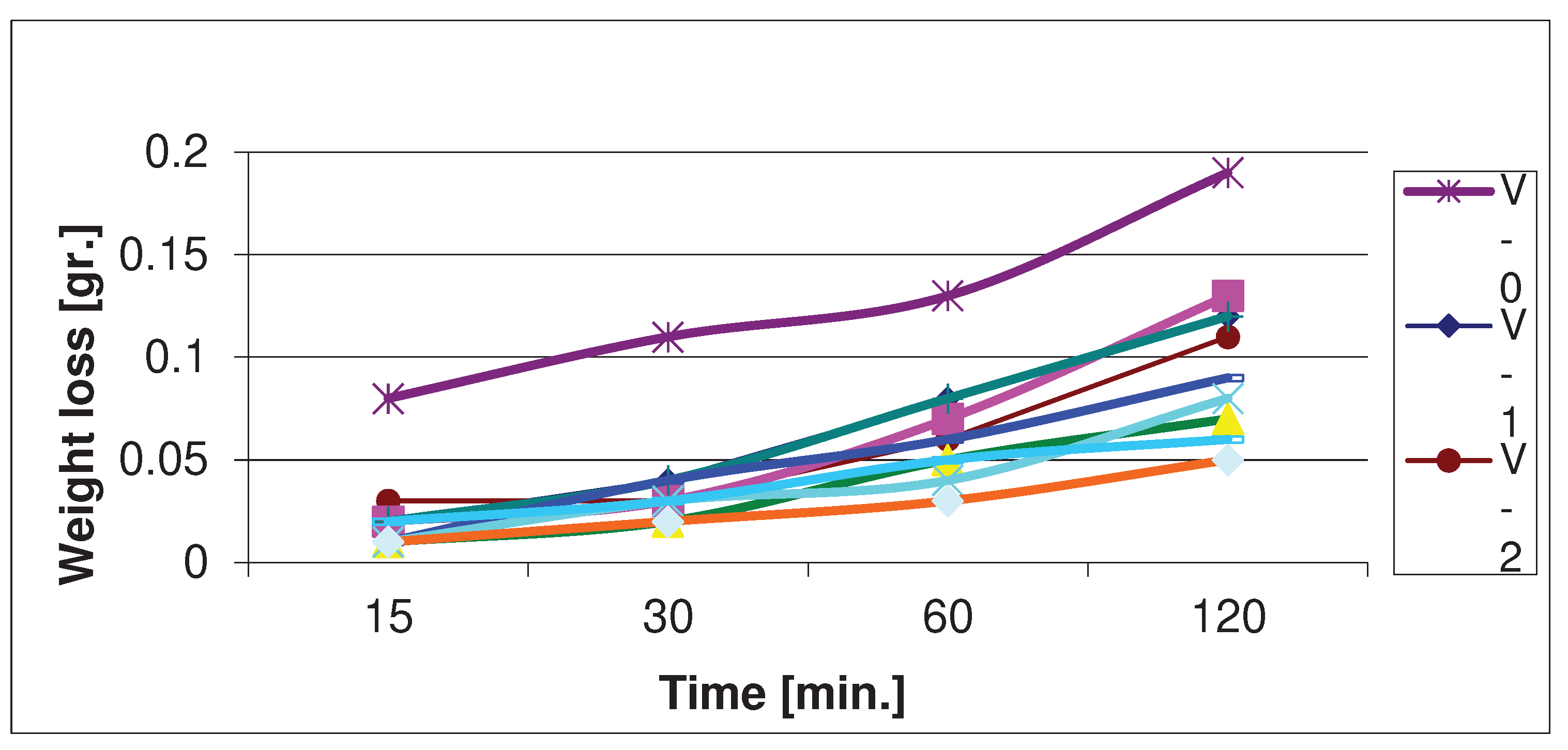

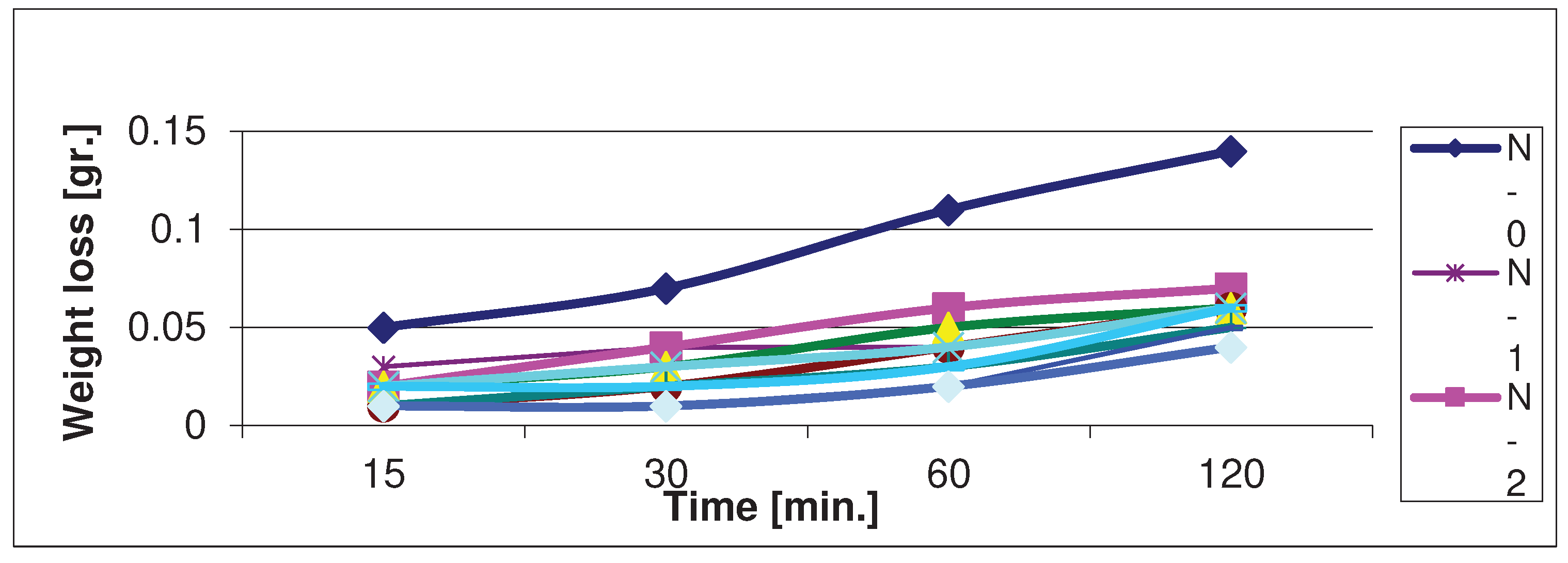

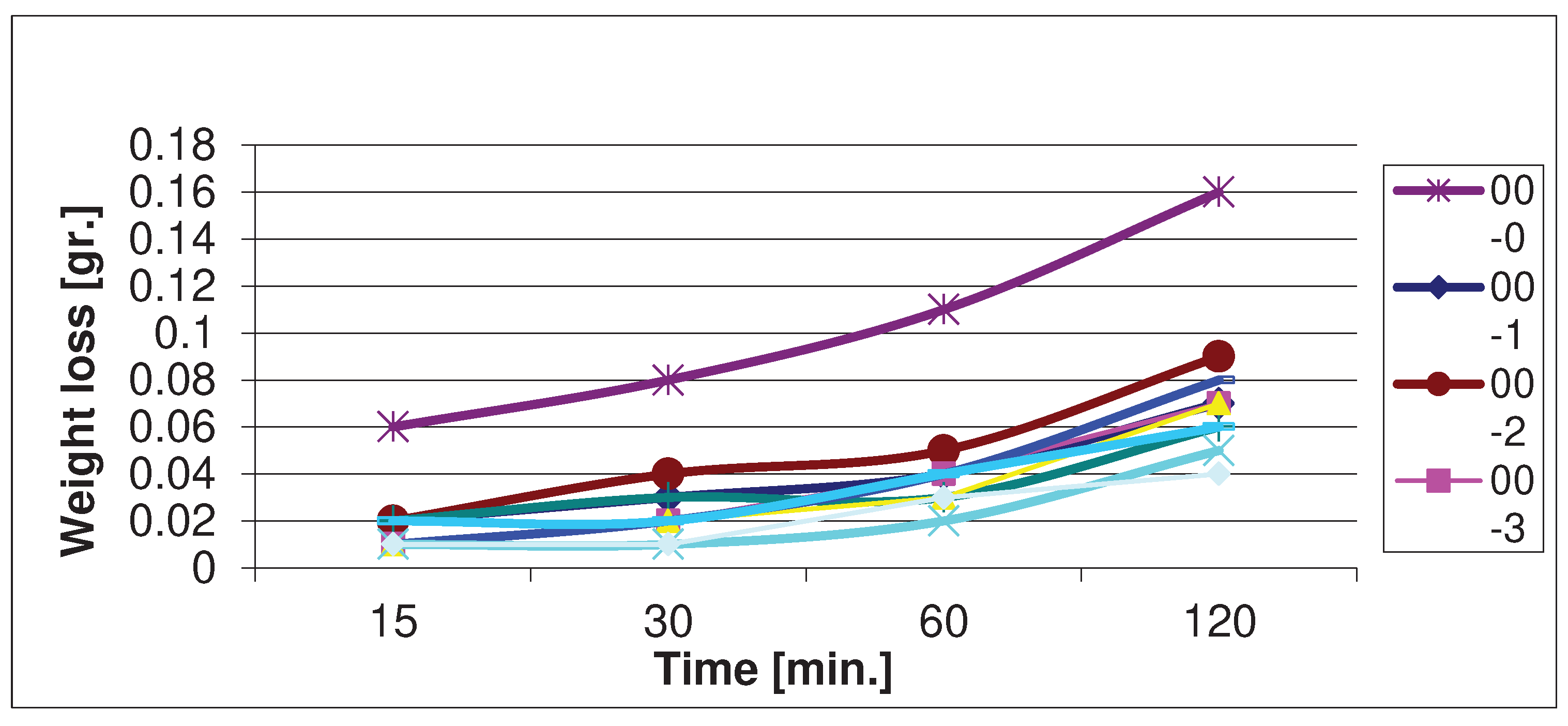

Abrasion resistance was tested after 15, 30, 60 and 120 min of abrasion and sample weighing. The loss of mass is determined using a balance "Oertling - England", with an accuracy of 10-2 grams. The results are shown in the abrasion graph,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10

Analyzing wear resistance of the samples, the laser-treated hardfacings generally present with 30–57% lower wear rates than reference untreated samples (K-0 and N-0, respectively), which could be due to the formation of hard phases (chromium carbides, martensite and residual austenite) in the bulk of the cladding.

The obtained coating surfaces show significant roughness values, as demonstrated from the 3D AFM topographic images [

7]. An increase in surface roughness profile was noted with increasing laser power, possibly due to constitutive morphological reconstruction, aided by improved elemental scattering. In addition, the presence of intermetallic compounds or carbides on the surface of the sample, embedded in the ferrite matrix can also be considered. The surface energy is an important parameter, which is directly related to the corrosion resistance of the sample and the ability of the surface to better interact with different species with similar surface energy values (for example: with primers, paints, other metals, polymers, etc.). For the reference samples, the main component of the surface energy is the dispersion component. It can be noted that the K-0 sample has the lowest surface energy, possibly due to the higher amount of chromium present on the surface of the material.

4. Conclusion

Characterization of hard surfaces obtained after coating with the 62 H electrode, mainly in solid solution enhanced with brown shades (ferrite, austenitic, martensite), with intermetallic compounds (possibly (Fe) ), Mn)3Si) takes place at the grain boundary. The majority of these compounds were observed to be present in the treated sample, emerging with the highest laser energy densities. It is observed that in the case of coatings with low Cr content, the heat treatment of the laser beam affects the precipitation of C and Cr carbides, increasing with the intensity of the laser beam. In addition, the formation of needle-like martensitic structures can be observed.

Study on the effect of post-processing technique on microstructure and fracture strength of Inconel 718 fabricated by AM process. Constructed samples contain γ-column dendrites and small amounts of gamma+Laves eutectics in interphase. After using direct aging, a heat treatment process, heterogeneous gamma′′/gamma′ accumulates around lava phases. After dissolution + aging, delta phases accumulate into Laves phases, microdissociation decreases. After homogenization + dissolution + aging, the Lava phase almost disappears. [

28]

The microstructure of the hard surface obtained coating with the E 48 T electrode revealed the presence of carbides (spherical at N-0, arranged at grain boundaries at N-6 and N-7). The largest amount of carbide is found in sample N-7, which occurs with the highest laser power density. The EDS elemental mapping of the sample cross-sections also supports the formation of chromium carbide during laser heat treatment in the case of a hard coating deposited by the El62H electrode, with the highest chromium content. These carbides typically have a higher density relative to the rest of the coating material, which determines their migration into most of the coating, also aided by a high chromium concentration gradient between the coating and the material. Whether. base material. The reason that the apparent chromium content at the cross-sectional surface decreased with increasing laser power could be because no significant diffusion of this element was found in the base material. The surface is richer in Si and Mn, making the material more resistant to corrosion (the formation of silicide and intermetallic compounds), while the carbide ensures a higher wear resistance of the hard coating, also such as higher wear resistance. view from the picture. Firstly. For the hard coating produced by the E48 T electrode, a low chromium content (2.5% w/w) can determine a less pronounced amount of carbide formation than that of the L-types. The presence of Cr, W, V and Mo on the surface of L-type test pieces can also contribute to their increased resistance to corrosion. In addition, the sharp, clear separation boundary between the substrate material and the hard coating can act as a diffusion barrier, thereby retaining the Cr, W, Mo, V and Mn on the sample surface.

The formation of hard phases in most laser-treated hard coatings can be explained by the high values of microhardness, as shown in

Figure 1a,b. The formation of martensite, as well as chromium and carbide mixtures, can be explained by the remarkably high micro-hardness value in samples K-6 and K-7 (

Figure 2b), which is identical to that of pure martensite.

The furthest layer is characterized as the compound locale and the inward layer underneath is known as the dissemination locale. Each zone contributes to moved forward execution by progressing particular specialized properties, specifically wear resistance, grease, erosion resistance and weakness resistance. By considering the microstructure of the test coated with E 62 H, which includes a tall concentration of C, the ferrite-pearllite structure of the base fabric and the structure of the needle-shaped martensitic structure can be watched. For the other five terminal sorts, the one with more C, more pearly structures were gotten. The base fabric includes a ferrite-pearlite structure, with pearlite lamellar. Based on the look range, columnar dendrite structures can be watched within the Fe network with god boundary. From these, advance execution benefits are realized: fabulous running properties, anti-wear and anti-wear properties, and decreased propensity to terrible erosion. By examining the SEM structures, appeared in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, microhardness (

Figure 6) and scraped area resistance (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), a great relationship between hardness can be watched. micro-hardness and wear resistance, which increments the unequivocal increment of wear-resistant micro-hardness. After a moo escalated laser surface warm treatment, the structure of the fabric is changed, coming about in halfway change of ferrite into pearls with a better C concentration, which increases the mechanical properties. Within the case of tall concentrated laser surface warm treatment, more noteworthy than 2000 W, the arrangement of remelting structures can be watched, coming about in altogether expanded mechanical properties.

Scraped area resistance is maybe the foremost critical property determined from this surface treatment. The wear resistance of the composite zone depends on the sort of anti-wear framework, especially whether it is cement or grating wear. Colloidal wear happens when two components are in relative movement in a non-abrasive base medium. Beneath these conditions, the natural physical properties of the compound, specifically hardness and lubricity, altogether move forward the sliding and running behavior and in this way increment the cement wear resistance. The stage composition of the mixed locale appearing the finest wear resistance is mainly composed of an epsilon nitride stage (single stage favored) with an awfully little sum of the gamma essential stage. Scraped area resistance depends on the relative bundles of the rough and the composite locale.

References

- Torrisi, V.; Censabella, M.; Piccitto, G.; Compagnini, G.; Grimaldi, M.G.; Ruffino, F. Characteristics of Pd and Pt nanoparticles produced by nanosecond laser irradiations of thin films deposited on topographically-structured transparent conductive oxides. Coatings 2019, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias, M.; Zimbone, M.; Boutinguiza, M.; Del Val, J.; Riveiro, A.; Privitera, V.; Grimaldi, M.G.; Pou, J. Synthesis and deposition of Ag nanoparticles by combining laser ablation and electrophoretic deposition techniques. Coatings 2019, 9, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baino, F.; Montealegre, M.A.; Minguella-Canela, J.; Vitale-Brovarone, C. Laser surface texturing of alumina/zirconia composite ceramics for potential use in hip joint prosthesis. Coatings 2019, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayyad, A.; Bardon, J.; Hirchenhahn, P.; Vaudémont, R.; Houssiau, L.; Plapper, P. Influence of aluminum laser ablation on interfacial thermal transfer and joint quality of laser welded aluminum–polyamide assemblies. Coatings 2019, 9, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayel, I.M. Thermoelastic response induced by volumetric absorption of uniform laser radiation in a half-space. Coatings 2020, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, H.; Xu, X. Experiment study of rapid laser polishing of freeform steel surface by dual-beam. Coatings 2019, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penide, J.; del Val, J.; Riveiro, A.; Soto, R.; Comesaña, R.; Quintero, F.; Boutinguiza, M.; Lusquiños, F.; Pou, J. Laser surface blasting of granite stones using a laser scanning system. Coatings 2019, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. Microstructures and wear resistance of FeCoCrNi-Mo high entropy alloy/diamond composite coatings by high speed laser cladding. Coatings 2020, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopphoven, T.; Pirch, N.; Mann, S.; Poprawe, R.; Häfner, C.L.; Schleifenbaum, J.H. Statistical/numerical model of the powder-gas jet for extreme high-speed laser material deposition. Coatings 2020, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, W.; Pan, K.; Lin, X.; Wang, A. High temperature oxidation and thermal shock properties of La2Zr2O7 thermal barrier coatings deposited on nickel-based superalloy by laser-cladding. Coatings 2020, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas G., L. Li, U. Ghazanfar, Z. Liu. (2006). Effect of high power diode laser surface melting on wear resistance of magnesium alloys, Wear 260, 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Orazi L., A. Fortunato, G. Cuccolini, G. Tani. (2010). An efficient model for laser surface hardening of hypo-eutectoid steels, Applied Surface Science, 256 1913–1919. [CrossRef]

- Slatter T., H. Taylor, R. Lewis, P. King. (2009). The influence of laser hardening on wear in the valve and valve seat contact, Wear 267, 797-806. [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari M., M.G. De Flora. (2011). Influence of laser hardening on the tribological properties of forged steel for hot rolls, Wear 271, 2402–241. [CrossRef]

- W. Dai, X. Xiang, Y. Jiang, H.J. Wang, X.B. Li, X.D. Yuan, W.G. Zheng, H.B. Lv, X.T. Zu. (2011). Surface evolution and laser damage resistance of CO2 laser irradiated area off used silica, Optics and Lasers in Engineering 49, 273–280.

- A Oláh, C Croitoru, MH Tierean - Surface properties tuning of welding electrode-deposited hardfacings by laser heat treatment, Applied Surface Science 438, 41-50, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Oláh A., Tierean M.H. - Research about relation between the microstructures and mechanical properties of metal coating layers, AMS Conference, Timisoara, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Machedon Pisu T., E. Machedon Pisu, O.L. Bigioi, Researches regarding the welding of 15NiMn6 steel used for spherical tanks, Metalurgia International, 02/2009, ISSN 1582-2214, 31-34.

- Chen, Y.; Peng, X.; Kong, L.; Dong, G.; Remani, A.; Leach, R. Defect inspection technologies for additive manufacturing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2021, 3, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Qi, Q.; Shi, P.; Scott, P.J.; Jiang, X. Automatic generation of alternative build orientations for laser powder bed fusion based on facet clustering. Virtual Phys. Phototyp. 2020, 15, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, A.; Guzzomi, F.; Rassau, A.; Hayward, K. Advances in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Common Processes, Industrial Applications, and Current Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.; Dezfoli, A.; Lo, Y.-L.; Mohsin Raza, M. 3D Multi-Track and Multi-Layer Epitaxy Grain Growth Simulations of Selective Laser Melting. Materiaals 2021, 14, 7346. [Google Scholar]

- Jinoop, A.N.; Subbu, S.K.; Paul, C.P.; Palani, I.A. Post-processing of Laser Additive Manufactured Inconel 718 Using Laser Shock Peening. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2019, 20, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Cai, Z.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Peng, P.; Guo, W. Effects of heat treatment combined with laser shock peening on wire and arc additive manufactured Ti17 titanium alloy: Microstructures, residual stress and mechanical properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 396, 125908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Pegues, J.W.; Mahjouri-Samani, M.; Shamsaei, N. Laser polishing for improving fatigue performance of additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V parts. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Arif Mahmood 1, Diana Chioibasu 1, Asif Ur Rehman 2,3,4, Sabin Mihai 1,5 and Andrei C. Popescu - Post-Processing Techniques to Enhance the Quality of Metallic Parts Produced by Additive Manufacturing, MDPI – Metals12(1), 77, 2022.

- Yu, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, W. Influence of post-heat-treatment on the microstructure and fracture toughness properties of Inconel 718 fabricated with laser directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 798, 140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chaudhari, A.; Wang, H. Investigation on the microstructure and machinability of ASTM A131 steel manufactured by directed energy deposition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 276, 116410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.G.; Machado, C.M.; Duarte, V.R.; Rodrigues, T.A.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Effect of milling parameters on HSLA steel parts produced by Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 59, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).