Introduction

The conceptualization of Quality Physical Education (QPE) was proposed by United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1978. Its fundamental intention was to embed the provision of physical education (PE) in schools globally. Interestingly, a tailored QPE program facilitates an active lifestyle and helps understand the essence of promoting lifelong physical fitness including enhanced peer-led learning that further maximizes physical, social, emotional well-being, and motor skills (Masurier and Corbin, 2013). These all domains help profusely to address three key global crises (which were further impacted majorly due to the recent COVID pandemic) such as physical activity (PA) (decreased by 41%), mental health (worsened tremendously amongst students), and inequality (negatively impact PA participation in girls and disabled children) (UNESCO, 2015). The progress of QPE needs to advance with interest as this area leveraged rounded skills which can promote the didactic and employability outcomes of an individual (UNESCO, 2015).

PA is considered the best ‘Pill’ to enhance an active lifestyle (Salvo et al., 2021). Steaming to this consideration one proverb goes well as “Health is Wealth”, which signifies its essentiality for determining a sustainable healthy future for students (Baena-Morales et al., 2021). As such, sustainable physical activity (PA) (Bjørnara et al., 2017) is of paramount importance for achieving optimal health and active living (Bácsné-Bába et al., 2021). Regular practice of PA helps derived multiple health benefits (Pacesova et al., 2019) including averting numerous health risks (Piercy et al., 2018). To attain both the mentioned favorable rewarding outcomes, regularity in PA is identified to be the key aspect (World Health Organization, 2010). Per the WHO and the European Commission (EC) a minimum of 150 (moderate) / 75 (vigorous) minutes/per week PA, or a combination of the two is recommended for adults (World Health Organization, 2010). Failing to meet these recommendations leads to physical inactivity that is further linked with numerous non-communicable diseases (NCD) risks (such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, and others) and increased total mortality (Lee et al., 2012). Around >5.3 (9%) million people die annually due to physical inactivity globally (Lee et al., 2012).

The increasing physical inactivity identified as a burning issue globally and remains a pertinent discussion within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Baena-Morales et al., 2021; Salvo et al., 2021). The research by Baena-Morales et al., (2021), emphasized the links between PE lessons and the SDGs. It fosters the growth of students who contribute to a more sustainable world. Their study carefully examined all of the proposed SDGs to highlight those that were pertinent to PA and sports. However, the precise nature of PE's contribution to Agenda 2030 is not stated (Baena-Morales et al., 2021). Importantly, Synergies between PA advancement and meeting several of the SDGs are conceptually coherent and supported by scientific evidence (Salvo et al., 2021). For achieving these goals, QPE help in designing our commitments to perpetuating lifelong PA that eventually alleviates the dropout rate in PA (Hulteen et al., 2017). Dropout in PA is experienced by most students (Trude and Shephard, 2008), therefore this issue needs to be discussed elaborately and cautiously.

PE and PA in Saudi Arabia

It is not more than 6 decades ago when Saudis enjoyed a simple and active lifestyle. Their daily-based physical work alone remained sufficient to keep their body lean and in a petite shape (Al-Hazzaaa, 2004; Al-Hazzaab, 2004). However, the recent economic transformation with the advent of the technological revolution unequivocally brought tremendous changes to Saudi’s lifestyle in terms of induced sedentary behavior, decrease PA, consumption of caloric dense diet, and others (Al-Hazzaaa, 2004; Al-Hazzaab, 2004). Succinctly, all the mentioned factors enormously contributed to elevating NCDs in Saudi Arabia. Per the report of Alarabia News (2021), in 2021, > 25000 people died in Saudi Arabia because of cancer and diabetes. Furthermore, it is estimated that this number will be doubled (50,000) by 2025. Unfortunately, this debilitating condition targets mainly people between the ages of 20 to 39 years. The causes of these deaths are physical inactivity, sedentary behavior, and unhealthy eating habits. The exponential increase of non-communicable diseases in Saudi Arabia initiates substantial dialogue for finding strategies to de-escalate its inducing parabola remains in extreme prominence. Therefore, the idea of promoting a healthy and active lifestyle is firmly embedded in the Saudi Vision 2030 (Saudi Vision 2030) which aims to leverage “encourage widespread and regular participation in sports and athletic activities”.

Per UNESCO’s 2013 report, at the primary level children in Saudi Arabia received around 120 min. of PA/week, however, with the transition to the secondary level it declined to 45 min. of PA/week. This is less than other neighboring countries such as Qatar 75 min./week, Kuwait 40-135 PA/week, Bahrain 65 min. PA/week, Jordan 45-60 min. PA/week, and others. Furthermore, Saudi’s PA level is at the bottom notch of the middle average of 40-160 min. PA/week (UNESCO, 2013).

QPE, PA, and Motivation

Motivation is considered a critical factor for encouraging and maintaining regular PA. Motives are regarded as innate mechanisms that direct and motivate behavior. They can also be triggered by thoughts or emotions that support or contradict those needs, such as those related to plans or expectations for oneself (Reeve, 2009). As a result, there is a commonality among the three different categories of internal motives (such as needs, cognitions, and emotions) that justify why I want to do something.

Both extrinsic and intrinsic motives can be achieved during practice and when theorizing the motivations behind PA (Frederick and Ryan, 1993). Additionally, it has been discovered that exercise goal contents can be intrinsic or extrinsic, depending on how important they are to achieving the desired endpoint (such as weight reduction to have a fit and petite body shape) (Sebire et al., 2008). Therefore, the promotion of QPE programs in educational settings (such as staffing, facility, policy, and others) incentivizes students to actualize their participation and increase regularity for a sustainable PA (Baena-Morales et al., 2021). In particular, student motivation alone cannot bring inclusivity unless quality components are not being thoughtfully incorporated into PE programs. In this case, the sustainability vision sought to ascertain whether QPE had access to enough resources to support PA's primary motivation and the corresponding student behavior. There isn't much hard evidence to support this claim, though.

The self-determination theory (SDT) clearly explains how motives can satisfy fundamental psychological needs like relatedness (believing that one is not emotionally isolated from others), competence, and autonomy (believing that one's actions are what caused them), all of which are essential building blocks for the growth of positive motivation and personal development (Deci and Ryan, 2017). Promoting intrinsic motivation (such as student-favorite sports), teacher support, expanding students' perceptions of their competence, improving PA values (Salvo et al., 2021), and community-based initiatives are crucial if PA is to be sustained. It is critical to ensure that adolescents have access to enough QPE before attempting to increase their motivation for PA. Questions like "Is there a suitable facility for PE?" and "Do students have a secure environment for PE?" were raised by Ho and others (2012). The main query raised by the aforementioned discussion is "Why," given the numerous rewarding health benefits of PA, do we frequently fall short in our efforts to promote sustainable PA? to build a healthy, long-lasting future?

This study

The alarming decline in kids' participation in healthy activities like PE (Ahmed, 2017) contrasts sharply with the rise of screen watching (Chahal et al., 2013). As teenagers get older and move from high school to college, it has been found that PA tends to decline (Maselli et al., 2018). University years remain critical for leveraging and continuing a healthy and active lifestyle. Unfortunately, despite the numerous benefits offered by PA, a significant percentage of university students do not meet prescribed recommendations. PA has been recommended to be encouraged in educational institutions by fostering intrinsic motivation (sports favoritism), teacher support, improving students' perceptions of their competence, and promoting PA values by informing students about its health benefits (Codina et al., 2016). However, there are causes for concern regarding the link between higher education and decreased PA. Because universities in many counties were found hardly ever encourage students to participate in PA (Mella-Norambuena et al., 2019). But there is a reason for optimism because college is also a period when individuals can develop healthy habits and ways of life (Maselli et al., 2018). Moreover, a country’s sustainable future (health, economy, and others) depends on its purely healthy young generation. Because embedding active lifestyle habits during the early adolescence period remains remarkable for a sustainable healthy transition into adulthood. Due to these factors, it remains critical to comprehend both the personal factors and contextual factors (related to this behavior) that influence university students' participation in PA (Lindwall et al., 2016; Caro-Freile and Cobos, 2017). Support from others (such as a team or family members) or the planning and scheduling of the activity are all important contextual (Codina et al., 2020).

The vision of sustainability in this context was to help identify whether there is adequate provision for QPE to advocate the motive of sustainable PA and its underlying behavior among students. However, this claim is not well supported by empirical evidence. Therefore, furthering the research of QPE was remain promising in terms of describing students’ motives for sustainable PA. Grounded in self-determination theory, the study highlights the three broad research questions are delineated as follows:

- (i)

Do the motive of PA participation can be enhanced through the quality provision of PE programs in university settings

- (ii)

Does the quality provision of PE help promote sustainable PA among adolescents? and

- (iii)

Does gender have an impact on this carry-over process?

Methodology

Permission

Permission to conduct this cross-sectional study (Reference number: 2021/PMU/3rd FS) was obtained from Prince Mohammed Bin Fahad University (PMU), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, this research grant is initiated by the collaboration of the Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd Center for Futuristic Studies (PMFCFS) and the World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF).

Participants

To meet the study’s aims N = 610 (male (n = 467) and female (n= 143)) students who studied PE courses participated in this study. Participants were recruited across all the departments of the university and involved in > 27 different sports. The participants' mean ages were 20.76 (SD: 3.47), and they had an average of 4.70 (SD: 4.93) years of athletic experience. Participation in the study was completely voluntary. This means they could leave the study at any time, at their discretion, and without obtaining the PI's prior approval. The data collection was concluded within 4 months of the proposal’s acceptance date.

Procedure

After receiving the grant approval, the principal investigator contacted the concerned authorities for the data collection. Next, participants were approached through the university’s internal portal system. Especially, the invitations were sent to those students who have studied PE as a requirement of your degree program. Upon receiving the participation confirmation, students were guided on how to proceed with the survey. Participants were then informed about the meeting place at the university. The survey was conducted on different dates for which participants were informed in advance. Participants sitting arrangement for the survey was conducted in the PMU’s main auditorium, lecture halls, and classrooms. The participants were given a thorough explanation of the study's goals before the data collection began. Also, it was informed that their participation in the study was voluntary, they can quit the survey at any time without prior permission. There were two sections to the questionnaire packet. Biographical details were compiled in the first section (e.g., age, sport, number of years participating). The questionnaires listed below were filled out by participants in the second section.

Measures

Quality Physical Education (QPE)

To measure the student's perception of quality PE provision in university settings, the professional Perception of QPE (PPQPE) devised by Ho, Ahmed, and Kukurova (2021) was implemented. It consists of 48 items and eight dimensions. The 8 dimensions covered skill development and bodily awareness, facilities and norms in PE, quality teaching of PE, plans for feasibility and accessibility of PE, social norms and cultural practice, governmental input for PE, cognitive skills development, and habituated behavior in physical activities (Ho et al., 2021). Excellent psychometric properties and an internal consistency range of =.824 to =.935 were provided by the questionnaire. Items were responded on a 6-point (i.e., strongly disagree = 1, mostly disagree = 2, slightly disagree = 3, moderately agree = 4, mostly agree = 5, and strongly agree = 6) rating scale. Sample items are as follows “School should have a safe and suitable environment for PE lessons”, “PE should be accessible to all children, whatever their ability/ disability, sex, age, cultural, race/ethnicity, religious, social or economic background” (Ho et al., 2021).

Need satisfaction

The Psychological Needs Satisfaction in Exercise (PNSE) Scale devised by Wilson, Rogers, Rodgers, & Wild, (2006) was employed to determine how students typically feel about exercise. The scales consisted of 18 items and comprised three subfactors namely i. PNSE-Perceived Competence (α = 0.91, same items are as follows “Confident I can do challenging exercise”), ii. PNSE-Perceived Autonomy (α = 0.91, sample item “Free to choose exercises I participate in”), and iii. PNSE-Perceived Relatedness (α = 0.90, sample item (“Connected to people I interact with”). Items were responded to on a 6-point Likert scale. Greater satisfaction with each need is indicated by higher scores.

Physical Activity Assessment

The Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ), constructed by Godin and Shepherd in 1985, was used to examine the amount of moderate and vigorous PA (MVPA) that students engaged in during their free time. Participants had to report about their past 7-day period (a week) on the questions such as “During their leisure time how often do they involve in an activity that helped them to be sweated?” Considering 7 days (a week), during your leisure time how often do you engage in any regular activity long enough to work up a sweat (heartbeats rapidly)?”. Higher scores represent a more vigorous PA. Responses were garnered on a 7-point rating scale. LTEQ is widely implemented in PE and PA to identify the intensity and nature of activities (Martin et al., 2007). In this study, students were asked if they have performed any of the listed PA items mentioned in the questionnaire for more than 15 minutes during their leisure time. Participants' responses helped identify their engagement in activities for gauging cardiorespiratory fitness levels.

Data Analysis

To measure the variability of the data descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation (SD), and percentages) were employed. Pearson’s correlation was implemented to examine the relationship among the factors of different constructs. The reliability of the subfactors was computed using Cronbach’s alpha. Furthermore, regression analysis was used to determine the role that QPE played in the prediction of PNSE. Finally, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to examine whether or not gender has an impact on this carry-over process. Data were then computed using a 2 (Gender) by 2 (Type of Sport: Individual vs. Team) MANCOVA, with the covariate being age. As an adjunct to the MANCOVA results, eta-squared (η2 ) values were calculated and interpreted against Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, where 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, and 0.14 = large differences.

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS and R.

Primary analysis

Missing data analysis

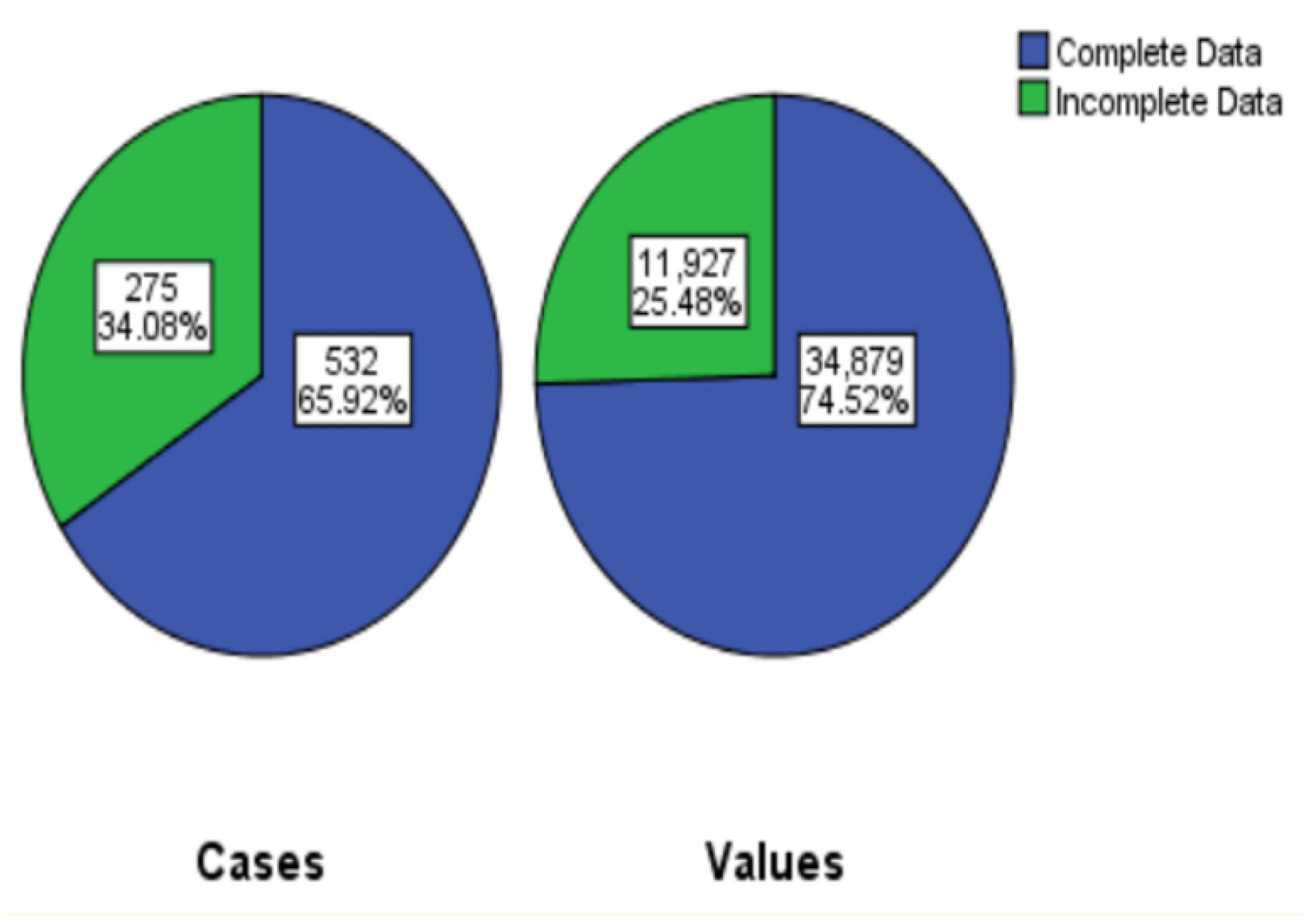

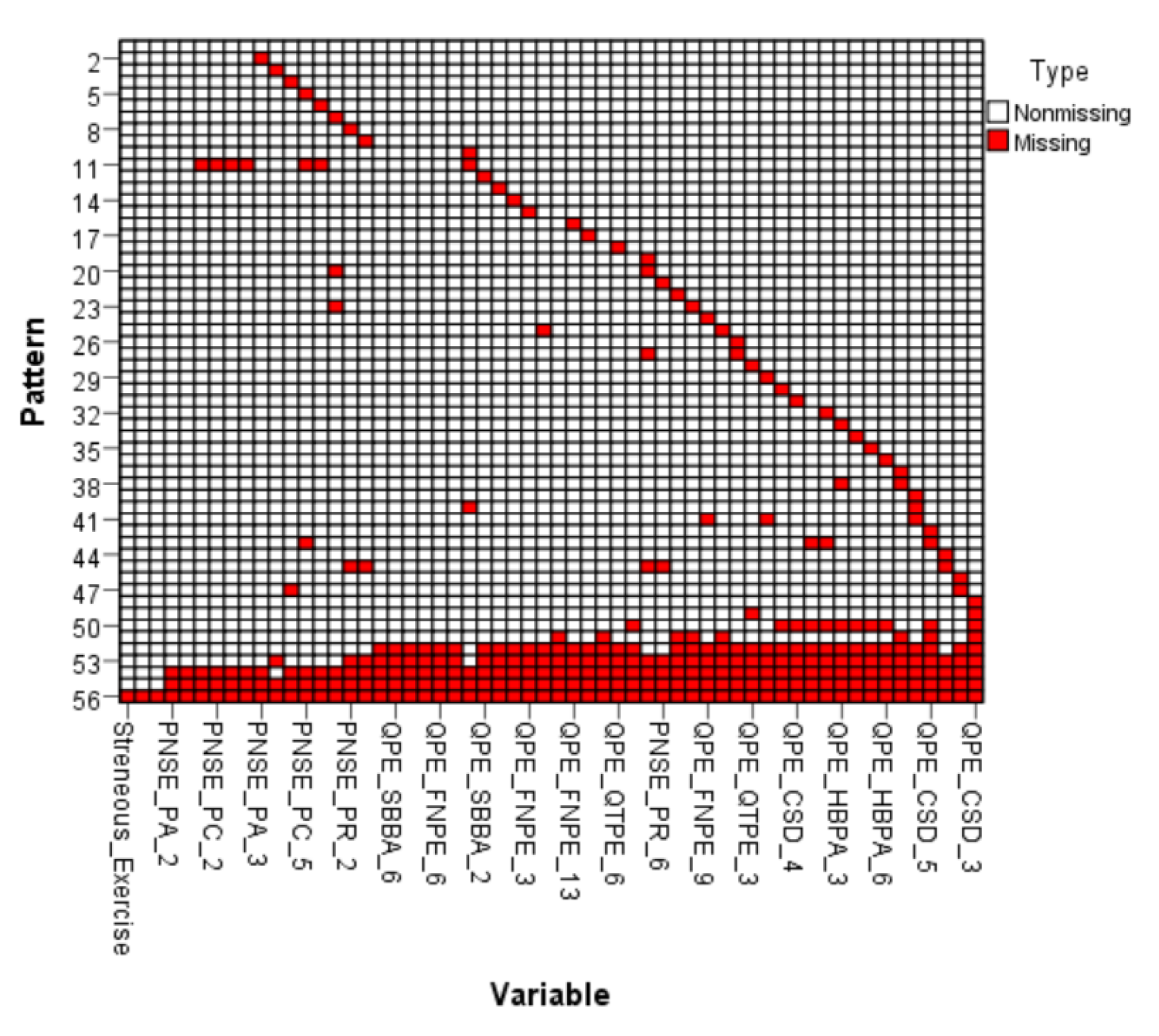

The study’s invitation was sent to 850 subjects, of which N = 610 (72.76%) participants returned with the completed survey questionnaires. To check the missing-value patterns of data, Little’s multivariate test of Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) (Little, 1988) was implemented.

Little’s test has the efficacy to check differences in variables spanning subgroups that comprise a similar pattern of missing data. The test provided 𝛘2 distance (df =2853) = 3348.004, p = .000, identified that the data were not missing completely at random under significance level 0.00. The items’ frequency analysis using the MCAR test helped identify missing values that failed to count on other variables. Therefore, multiple imputations were incorporated to impute the dataset. This technique works efficiently for producing adequate assessment (for the data MCAR) over the other outdated approaches (such as listwise and pairwise deletion). Item analysis for the QPE questionnaire was employed to examine the responses of the participants. To meet the purpose, frequencies, and percentages for each of the individual statements were computed using the original unimputed dataset.

Figure 1.

Overall summary of missing data.

Figure 1.

Overall summary of missing data.

Figure 2.

Missing values patterns.

Figure 2.

Missing values patterns.

Results

Pearson’s correlations showed significant correlations among all the subfactors of QPE and exercise need satisfaction. However, levels of PA did not report any correlation with either QPE or the need for satisfaction in exercise. Interestingly, the subfactors of QPE and need satisfaction in exercise provided sound reliability scores.

Multiple regression analysis (

Table 2) was computed to examine the variability to which need satisfaction in exercise, and PA is influenced by the QPE. As a preliminary analysis, multicollinearity was checked, if existed. The analysis did not report any multicollinearity as the tolerance level for all the factors reported < 0.1 and for VIF (variance inflation factor) >10. The analysis indicated the three predictors combined signified 63.4% of the variance (R

2 =.40,

F(3,606)= 135.95,

p<.05). The result highlighted that QPE significantly predicted PNSE-Perceived Competence (

β = .199,

p<.05), PNSE-Perceived Autonomy (

β = -.336,

p<.05), and PNSE-Perceived Relatedness (

β = -.249,

p<.05). Furthermore, the three predictors for physical activity explained 15.5% of the variance (R

2 =.019,

F(3,606)= 4.97,

p<.05). It was found that QPE significantly predicted Moderate Exercise (

β = .088,

p<.05), and Mild Exercise (

β = .107,

p<.05).

Table 1.

Correlation matrix of the variables and Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix of the variables and Cronbach’s alpha.

| |

Mean |

SD |

QPE

SDBA |

QPE

FNPE |

QPE

QTPE |

QPE

CSD |

QPE

HBPA |

PNSE Perceived Competence |

PNSE Perceived Autonomy |

PNSE Perceived Relatedness |

Strenuous Exercise |

Moderate Exercise |

Mild Exercise |

α |

| QPE SDBA |

33.80 |

7.34 |

1 |

.856** |

.791** |

.638** |

.733** |

.478** |

.492** |

.478** |

-.006 |

.078 |

.101* |

.904 |

| QPE FNPE |

63.70 |

13.20 |

|

1 |

.844** |

.663** |

.784** |

.440** |

.515** |

.457** |

-.020 |

.109** |

.138** |

.943 |

| QPE QTPE |

28.55 |

6.36 |

|

|

1 |

.735** |

.794** |

.461** |

.496** |

.461** |

-.016 |

.076 |

.108** |

.886 |

| QPE CSD |

18.85 |

4.67 |

|

|

|

1 |

.778** |

.418** |

.473** |

.369** |

-.031 |

.120** |

.078 |

.894 |

| QPE HBPA |

28.40 |

6.30 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

.421** |

.464** |

.444** |

-.039 |

.122** |

.114** |

.891 |

| PNSE Perceived Competence |

26.67 |

7.06 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.496** |

.494** |

.041 |

.116** |

.092* |

.909 |

| PNSE Perceived Autonomy |

27.90 |

6.59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.432** |

.007 |

.091* |

.039 |

.874 |

| PNSE Perceived Relatedness |

25.83 |

6.39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.017 |

.071 |

.098* |

.815 |

| Strenuous Exercise |

40.31 |

22.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.054 |

.041 |

- |

| Moderate Exercise |

20.21 |

9.98 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.225** |

- |

| Mild Exercise |

11.74 |

4.95 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

- |

To examine the interaction of the variables in male and female participants MANCOVA was computed with the covariate being age and sports type. A main effect difference in Exercise satisfaction for Gender was observed and the effect was large for PNSE Competence (Wilks' λ = .98, F (1, 608) = 9.16, p <.003, η2= .015). Also, a main effect of Sports Type has been identified for PNSE Relatedness (Wilks' λ = .97, F (1, 608) = 4.617, p <.010, η2= .015). There was no observed interaction effect (Gender * Sports Type). A main effect difference in Physical Activity for Gender was observed and the effect was moderate for Mild Exercise (Wilks' λ = .96, F (1, 608) = 11.73, p <.000, η2= .013), Strenuous Exercise (Wilks' λ = .97, F (1, 608) = 8.03, p <.012, η2= .013), and Moderate Exercise (Wilks' λ = .97, F (1, 608) = 6.79, p <.009, η2= .011). The subfactors of QPE did not show any significant differences between the sexes.

The results of the participants’ PNSE scores are presented in

Table 3. Male participants demonstrated a higher mean score in PNSE than females. The PNSE’s subfactors were compared between the sexes using independent t-tests. The PNSE-Perceived Competence highlighted a significant difference between male (M = 27.22±6.73) and female (M = 27.23±7.26;

t(608) = 3.47, p < 0.05, two-tailed) participants. The magnitude of the difference between the means (MD = 2.32, 95% CI) was large (eta squared = 0.33). This signifies that male students have significantly higher PNSE-Perceived Competence than their female counterparts. On the contrary, PNSE-Perceived Autonomy (male (M = 28.10±6.36) and female (M = 24.89±7.79;

t(608) = 1.38,

p > 0.05, two-tailed)); and PNSE-Perceived relatedness (male (M = 26.19±6.08) and female (M = 24.62±7.18;

t(608) = 2.58,

p > 0.05, two-tailed)) did not show any significant gender differences.

The results of the participant’s perception of the quality provision of PE in school setting scores are shown in

Table 4. Mean differences in gender on subfactors of QPE were analyzed using independent

t-tests. None of the subfactors (SDBA for male (M = 33.88±7.04) and female (M = 33.54±8.26;

t(608) = .481, p > 0.05, two-tailed); FNPE for male (M = 63.83±12.81) and female (M = 63.31±14.45;

t(608) = .410, p > 0.05, two-tailed); QTPE for male (M = 27.22±6.73) and female (M = 24.89±7.79;

t(608) = 3.47, p > 0.05, two-tailed); CSD for male (M = 27.22±6.73) and female (M = 24.89±7.79;

t(608) = 3.47, p > 0.05, two-tailed); and HBPA for male (M = 27.22±6.73) and female (M = 24.89±7.79;

t(608) = 3.47, p < 0.05, two-tailed)) showed any significant differences between the scores of male and female students.

The magnitude of the difference between the means of the subfactors such as SDBA (MD = .337, 95% CI) was small (η2 = 0.04), FNPE (MD = .518, 95% CI) was small (η2 = 0.03), QTPE (MD = .525, 95% CI) was small (η2 = 0.08), CSD (MD = .014, 95% CI) was small (η2 = 0.00), and HBPA (MD = .415, 95% CI) was small (η2 = 0.06). This implies that participants did not show any significant difference in their perception of QPE provision.

Participants' PA levels are provided in

Table 5. The result of independent samples

t-tests highlighted that in comparison to females, males are involved in more PA. The strenuous PA levels of male students (M = 41.75±23.88) were significantly higher than female students (M = 35.62±15.02;

t(608) = 2.89,

p < 0.05, two-tailed). The magnitude of the difference between the means (MD = 6.12, 95% CI) was large (η

2 = 0.28). Similarly, the moderate PA levels of male students (M = 20.77±10.05) were significantly higher than female students (M = 18.39±9.57;

t(608) = 2.50,

p < 0.05, two-tailed). The magnitude of the difference between the means (MD = 2.37, 95% CI) was large (η

2 = 0.24). Also, the moderate PA levels of male students (M = 20.77±10.05) were significantly higher than female students (M = 10.55±5.60;

t(608) = 1.56,

p < 0.05, two-tailed). The magnitude of the difference between the means (MD = 1.56, 95% CI) was large (η

2 = 0.32).

Discussion

This study begins by investigating whether the quality provision of PE programs in university settings can enhance psychological needs satisfaction in exercise among university students. The study also attempted to examine whether the QPE provision contributes to the sustainability of PA. Finally, it was investigated whether gender has an impact on this carry-over process.

Male students reported a high Mean = 27.22 (SD=6.73) value in comparison to female students (M = 24.89, SD = 7.79) in PNSE-perceived competence. The factor assesses a person’s ability to exercise satisfaction. This finding may be linked to the fact that male participants perceived the activity they performed may be more enjoyable and satisfactory than their female counterparts. The provided connotation is also aligned with several preceding studies. The study of Alhakbany et al., (2018) and Al-Hazzaa, (2018) eloquently reported the inconsistency of physical activity among Saudi women. This crisis has elevated obesity in this population as 91.10% do not engage in physical activity (Alqahtani et al., 2021). Importantly, this health disparity is more connected to several barriers which they face in their day-to-day life such as household responsibilities, unavailability of gym facilities in the vicinity, lack of motivation (Al-Otaibi, 2013; Awadalla et al., 2014), and others.

When someone chooses trials that are appropriate to their level of abilities is considered to be perceived competence. This means, societal and cultural norms have a tremendous impact on influencing women’s attitudes toward participation in PA and sports (Hartmann-Tews, 2003). Women may be especially drawn to a setting where PA is welcomed without regard to gender. Therefore, it is important to make sure that women are sufficiently encouraged to participate in different PAs on par with men. Otherwise, barriers may increase mental pressure and limit their ability to actively participate in PA (Hamdan, 2005). Any exercise programs should be carefully planned with a high level of perceived ability or attainability in mind. Such deliverance remained critical in developing sustainable PA among students. Because perceived competence helps in learning a new set of exercise skills (Mobaraki & Soderfeldt, 2010; Lysa, 2020). Furthermore, perceived autonomy and perceived relatedness for exercise satisfaction did not show any significant differences between the sexes.

The subfactors of QPE did not show any significant differences between the sexes. This highlights that the participants perceive their university program to be adequate in disseminating QPE. They may perceive that PE curricula could promote self-awareness about their own bodies and weight reduction. Furthermore, it signifies that their program possesses a structured PE curriculum, including providing an adequate safety environment with suitable equipment and facilities for the advancement of QPE. Their non-difference in the response also advocates the possession of adequate course features and quality teaching that is inevitable for inducing the programs’ accountability and expectations. Participants might perceive that QPE helps develop creativity and enhance students thinking ability to handle daily problems, order them to enhance moral behavior, and promote in them socially acceptable thinking. Additionally, it enables students to make wise decisions about how to perpetuate a healthy lifestyle through regular PA.

When considering the mean score of PA levels (strenuous, moderate, and mild exercise), male participants outperform their counterparts, females. Numerous studies have also reported a similar PA pattern in males. Alqahtani et al. (2021)’s study highlighted that of the total male population, only 28.30% participate in PA. It means more than 71.70% of the male population did not engage in PA. Similarly, this number is high in females where only 8.90% reported being engaged in PA with around 91.10% did not state any participation. Similar to those mentioned in the previous paragraph, this finding is attributable to their cultural settings. Social perceptions and recognition influence their engagement in sports and PA. A lack of such provision may restrict them to focus more on home-based activities than those designed for outdoors or can perform in open spaces. Additionally, the recent technological transformation undoubtedly increases screen time, sedentary activities, and physical inactivity (Al-Hazzaac, 2004; Al-Hazzaab, 2018).

Aljehani et al. (2022) study showed a decrease in the level of PA among university female students. Around 62% of students fail to meet the WHO’s guidelines of performing 75 minutes of vigorous activity and almost 70% reported not being able to accomplish 150 minutes of moderate activity/week. The study further delineates several pertinent barriers that outperform their involvement in PA. Reportedly, academic overload, unavailability of sports facilities in the vicinity, gender roles, and cultural norms are some of the impediments that lacked their participation in PA (Aljehani et al., 2022; Almaqhawi, 2021). Surprisingly, they valued academics more than PA, and also, prefer to use their free time for rest (Aljehani et al., 2022). They revealed finding interest in walking outdoors, however, the lack of roadside footpaths (Aljehani et al., 2022), and hot weather (Aljehani et al., 2022; Almaqhawi, 2021) demotivate exercisers to a large extent. Moreover, lack of parental support has also been reported as one of the key barriers that impede their engagement in PA. Positive outcomes were valued as facilitators, along with family support and general health concerns (Aljehani et al., 2022).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study contributes to a better comprehension of gender perception of perceived competence for exercise satisfaction. The report of males scoring higher in perceived competence is more likely to be linked with the enjoyment of the. Therefore, female students should increase their involvement in PA which may help them assess their abilities for perceived competence in exercise satisfaction. The study highlights the adequacy of QPE in the university setting. However, female students reported insufficient involvement in PA.

Acknowledgments:

Cordial thanks to Dr. Muhammad Waqar Ashraf, Dr. Todd Alan Rygh, Dr. Izharul Haq, and Dr. Huson Joher Ali for providing their comments and suggestions to enhance the quality of this draft. Special thanks to all the participants for investing time in completing the survey questionnaires.

Funding

This project received a grant (Reference number: 2022/PMU/3rd FS) from Prince Mohammed Bin Fahd University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, this research grant is initiated by the collaboration of the Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd Center for Futuristic Studies (PMFCFS) and the World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Al Hazzaa, H.M. Prevalence of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia: a brief review. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2004, 10, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulteen, R.; Smith, J.; Morgan, P.; Barnett, L.; Hallal, P.; Colyvas, K.; Lubans, D. Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Why Teachers Adopt a Controlling Motivating Style Toward Students and How They Can Become More Autonomy Supportive. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hazzaa, H.M. Prevalence of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia: a brief review. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2004, 10, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Quwaidhi, A.; Pearce, M.; Critchley, J.; Sobngwi, E.; O'Flaherty, M. Trends and future projections of the prevalence of adult obesity in Saudi Arabia, 1992-2022. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2014, 20, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarabia News (2021). Alarming number of young people in UAE, Saudi Arabia diagnosed with cancer: Study. “Alarming” number of young people in UAE, Saudi Arabia diagnosed with cancer: Study. (2021, ). Al Arabiya English. https://ara. 20 May.

- Alhakbany, M.A.; Alzamil, H.A.; Alabdullatif, W.A.; Aldekhyyel, S.N.; Alsuhaibani, M.N.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Lifestyle Habits in Relation to Overweight and Obesity among Saudi Women Attending Health Science Colleges. J. Epidemiology Glob. Heal. 2018, 8, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hazzaa, H. M. The public health burden of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family & Community Medicine 2004, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia revisited: A systematic review of inactivity prevalence and perceived barriers to active living. Int. J. Health Sci. 2018, 12, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Aljehani, N.; Razee, H.; Ritchie, J.; Valenzuela, T.; Bunde-Birouste, A.; Alkhaldi, G. Exploring Female University Students' Participation in Physical Activity in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed-Methods Study. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 829296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqhawi, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators of physical activity among Saudi Arabian females living in the East Midlands. J. Taibah Univ. Med Sci. 2022, 17, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, H.H. Measuring Stages of Change, Perceived Barriers and Self efficacy for Physical Activity in Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Alqahtani, B.; Alenazi, A.M.; Alhowimel, A.S.; Elnaggar, R.K. The descriptive pattern of physical activity in Saudi Arabia: analysis of national survey data. Int. Heal. 2020, 13, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awadalla, N.J.; AboElyazed, A.E.; Hassanein, M.A.; Khalil, S.N.; Aftab, R.; Gaballa, I.I.; Mahfouz, A.A. Assessment of physical inactivity and perceived barriers to physical activity among health college students, south-western Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2014, 20, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.J.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, W.J.; Ma, B.; Liu, D. Multi-Source Generation Mechanisms for Low Frequency Noise Induced by Flood Discharge and Energy Dissipation from a High Dam with a Ski-Jump Type Spillway. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 14, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.R.; Alzubaidi, M.S.; Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Shah, Z. A Scoping Review to Find out Worldwide COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Underlying Determinants. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørnarå, H.B.; Torstveit, M.K.; Stea, T.H.; Bere, E. Is there such a thing as sustainable physical activity? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 27, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Freile, A.I.; Rebolledo-Cobos, R.C. Determinantes para la Práctica de Actividad Física en Estudiantes Universitarios. Duazary 2017, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Fung, C.; Kuhle, S.; Veugelers, P.J. Availability and night-time use of electronic entertainment and communication devices are associated with short sleep duration and obesity among Canadian children. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 8, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, N. , Pestana, J., Castillo, I., and Balaguer, I. “Ellas a estudiar y bailar, ellos a hacer deporte”: un estudio de las actividades extraescolares de los adolescentes mediante los presupuestos de tiempo [“Girls, study and dance; boys, play sports!”: a study of the extracurricular activities of adolescents through time budgets]. Cuad. Psicol. Dep. 2016, 16, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, C. M.; Ryan, R. M. Differences in motivation for sport and exercise and their relationships with participation and mental health. Journal of Sport Behavior 1993, 16, 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, A. Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements. Int Educ J. 2005, 6, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Tews I, Pfister G. Sport and Women: Social Issues in International Perspective; Routledge/ISCPES: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, W.K.Y.; Ahmed, D.; Kukurova, K. Development and validation of an instrument to assess quality physical education. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Masurier, G.; Corbin, C.B. Top 10 Reasons for Quality Physical Education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2006, 77, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindwall, M.; Weman-Josefsson, K.; Sebire, S.J.; Standage, M. Viewing exercise goal content through a person-oriented lens: A self-determination perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 27, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysa, C. Fighting for the right to play: women’s football and regime-loyal resistance in Saudi Arabia. Third World Q. 2020, 41, 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, M.; Ward, P.B.; Gobbi, E.; Carraro, A. Promoting Physical Activity Among University Students: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2018, 32, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella-Norambuena, J.; Celis, C.; Sáez-Delgado, F.; Aeloiza, A.; Echeverría, C.; Nazar, G.; Petermann-Rocha, F. Revisión sistemática de práctica de actividad física en estudiantes universitarios. 2019, 8, 37. 8. [CrossRef]

- Mobaraki, A.; Soderfeldt, B. Gender inequity in Saudi Arabia and its role in public health. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2010, 16, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacesova, P.; Smela, P.; Kracek, S. Personal well-being as part of the quality of life: Is there a difference in the personal well-being of women and men with higher level of anxiety trait regarding their sport activity ? Phys. Act. Rev. 2019, 7, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 5th ed; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical Activity Promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building Synergies to Maximize Impact. J. Phys. Act. Heal. 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudi Vision 2030 (2022) Quality of Life Program. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov. 2030.

- Saudi Vision 2030 (2022)2. Developments in Saudi sports following Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.tamimi. 2030.

- Sebire, S.J.; Standage, M.; Vansteenkiste, M. Development and Validation of the Goal Content for Exercise Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Importance of Perceived Competence in Fitness/Exercise Programming | The Sport Digest. (n.d.). Thesportdigest.com. Available online: http://thesportdigest.

- Trudeau, F.; Shephard, R.J. Physical education, school physical activity, school sports and academic performance. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 10–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2013). UNESCO-NWCPEA: World-wide Survey of School Physical Education – Final Report 2013. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco. 4822.

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on PA for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).