Submitted:

13 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

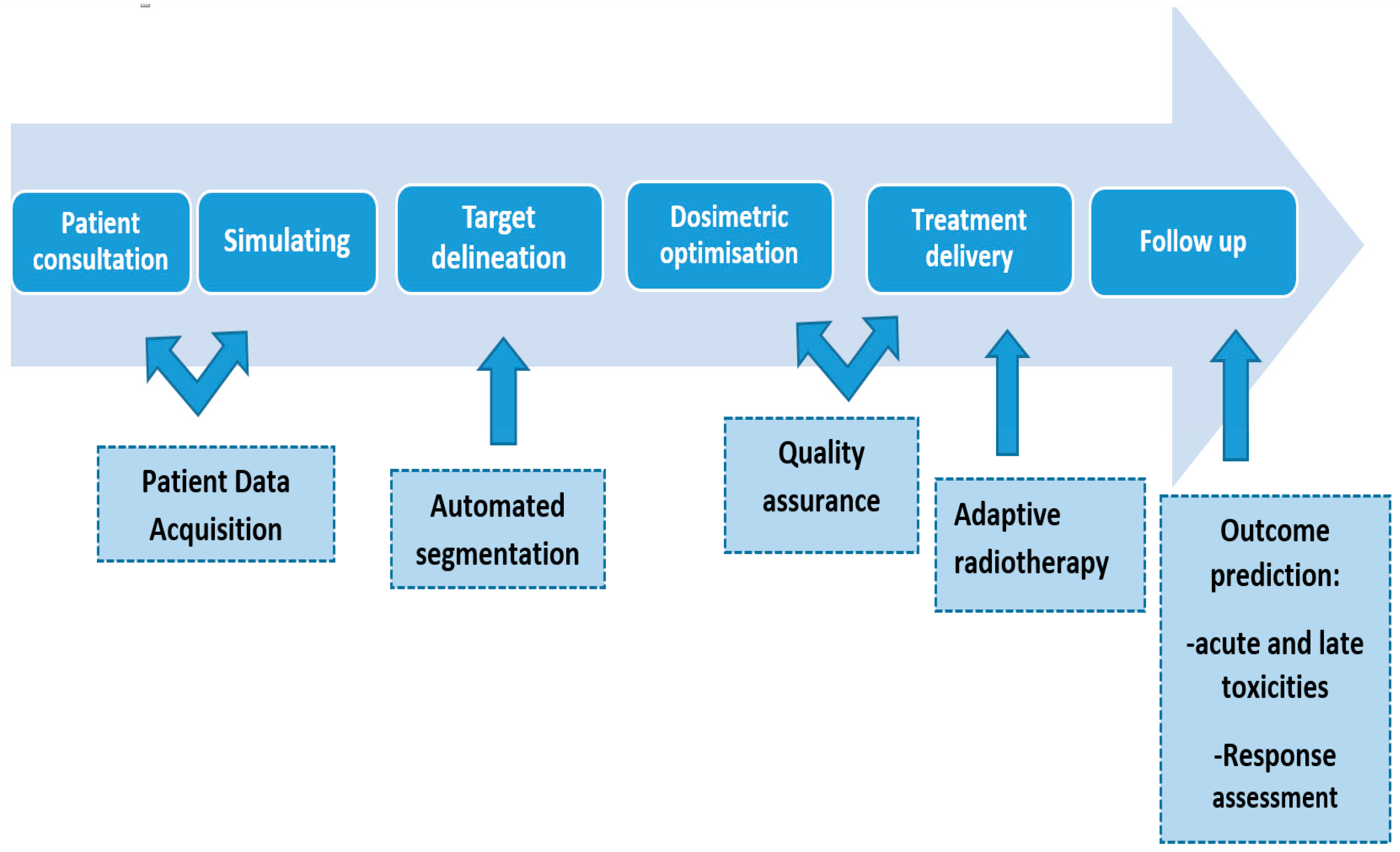

Introduction

- Automated Segmentation

- -

- Image Registration: The algorithm aligns the reference images (atlases) to the new target scan using image registration techniques. Image registration ensures that the anatomical structures in the atlases are aligned with those in the target scan, even if they have slight differences in position or orientation.

- -

- Atlas Fusion: Once the atlases are aligned with the target scan, the algorithm combines information from multiple atlases to create a fused or probabilistic representation of the segmentation. This fusion step helps to account for inter-subject variability and improves the accuracy of the final segmentation.

- -

- Segmentation Propagation: the fused atlas information is then propagated to the target scan to generate the final segmentation. This propagation can be achieved using various methods, such as deformable registration or label fusion techniques.

- -

- Insufficient adaptation to patient variability: Atlas-based methods rely on pre-segmented reference images, which might not adequately represent the variability in anatomy among different patients. This can lead to inaccuracies in segmenting structures, especially when dealing with patients who have unique anatomical variations or postsurgical changes.

- -

- Inadequate handling of local anatomical changes: Tumors or other pathological conditions can cause significant changes to local anatomy. Atlas-based algorithms may not be able to account for these changes appropriately, leading to systematic errors in the segmentations.

- -

- High manual editing requirements: The segmentations generated by atlas-based algorithms often require substantial manual editing by experts to achieve clinically acceptable results. This defeats the purpose of automation and can be time-consuming.

- -

- Automated Feature Learning: Deep learning models can learn hierarchical representations of the data, automatically discovering relevant features for segmentation tasks.

- -

- Higher Accuracy: Deep learning models have shown to outperform traditional methods, especially in complex and challenging segmentation tasks, due to their ability to learn intricate patterns and subtle differences.

- -

- Reduced Manual Intervention: These models reduce the need for extensive manual contouring, saving time and reducing inter-observer variability.

- -

- Generalization: Once trained on a diverse dataset, deep learning models can generalize well to new and unseen data, making them more robust in different clinical scenarios.

- -

- Scalability: Deep learning models can be trained on large datasets, allowing them to benefit from increased data availability and improving performance.

- -

- Variability in patient anatomy and image acquisition protocols: Each patient's anatomy is unique, and different medical centers may use various imaging protocols. This variability can lead to challenges in training AI models to handle diverse cases effectively.

- -

- Limited research datasets: AI models rely on large and diverse datasets for training, validation, and testing. However, there might be limitations in the availability of comprehensive and well-curated datasets, leading to potential biases or incomplete representations of certain anatomical structures.

- -

- Lack of quality assurance tools: Assessing the accuracy and reliability of AI-generated contours is essential in radiotherapy planning. The absence of standardized and efficient quality assurance tools can make it difficult to validate the accuracy of auto-segmentation results.

- -

- Clinical validation and regulatory hurdles: Incorporating AI tools into clinical practice requires thorough validation and regulatory approval. This process can be time-consuming and complex, slowing down the integration of AI technologies into routine clinical workflows.

- 2.

- Dosimetric and machine Quality Assurance

- -

- Dosimetric Quality Assurance and AI: Dosimetric QA involves verifying the accuracy of radiation dose delivery in radiation therapy. This is essential to ensure that the prescribed dose is accurately delivered to the target area while minimizing radiation exposure to surrounding healthy tissues [14].

- Treatment Planning: AI algorithms can assist in generating optimized treatment plans by analyzing patient-specific data, tumor characteristics, and radiation delivery constraints. These algorithms can help improve plan quality, reduce planning time, and enhance consistency.

- Dose Calculation: AI can be used to improve the accuracy and efficiency of dose calculation algorithms, ensuring that the delivered dose aligns with the planned dose.

- Treatment Plan Verification: AI can be utilized to verify treatment plans by comparing planned and delivered doses, identifying potential discrepancies, and suggesting necessary adjustments.

- Patient-specific QA: AI can aid in analyzing patient-specific data and historical treatment data to predict potential treatment-related issues or outcomes. This can help personalize treatments for each patient.

- -

- Machine Quality Assurance and AI: Machine QA involves ensuring the proper functioning and calibration of radiation therapy and medical imaging machines. Regular QA checks are necessary to guarantee the accuracy and safety of these devices [15].

- Image Quality Assurance: AI algorithms can be used to analyze medical images, assess image quality, and detect any artifacts or inconsistencies that may affect diagnosis or treatment planning.

- Fault Detection: AI can be integrated into the monitoring systems of radiation therapy machines and imaging devices to detect anomalies or malfunctions in real-time. This early warning system can help prevent potential errors.

- Automated Testing: AI-powered automation can streamline the QA testing process for machines, making it more efficient and reducing the burden on medical physicists and technologists.

- Predictive Maintenance: By analyzing data from the machines, AI can predict when maintenance is required, reducing downtime and optimizing the lifespan of the equipment.

- 3.

- Adaptive radiation therapy:

- Offline: between fractions to address slow progressive anatomical changes during the treatment course caused by weight loss and tumor regression.

- Online: before the fraction to consider for tumors with potentially significant interfractional target and normal structures variations, especially in the abdomen and pelvis radiotherapy.

- Real time: during the treatment of fractions to enhance the accuracy of radiotherapy for moving target suche as lung and liver cancer fundamentally improving safety and efficacy.

- -

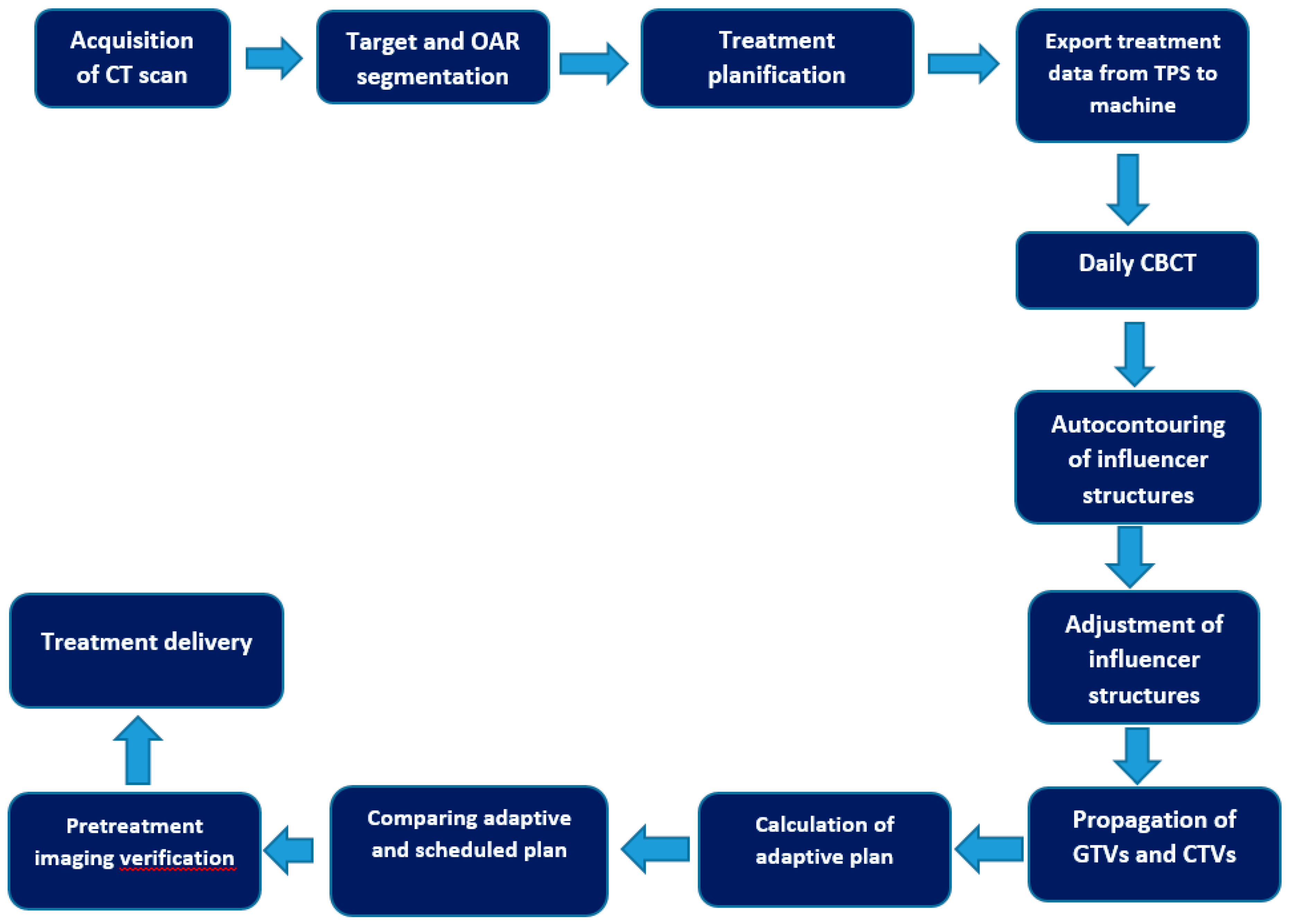

- Auto-contouring using AI: The process begins with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to automatically contour or delineate "influencer" structures. These structures are important in guiding the subsequent steps of the adaptive process.

- -

- Adjustment of Influencer Structures: After the AI-generated initial contours, a user (medical professional) can review and make adjustments to these influencer structures if necessary, ensuring their accuracy and relevance for the patient.

- -

- Structure-Guided Deformable Image Registration (DIR): The next step involves creating a deformable image registration (DIR) between the initial planning computed tomography (CT) scan and the acquired cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan. This DIR ensures that the images from different time points are aligned correctly.

- -

- Elastic DIR for Mobile and Non-Mobile Regions: Two types of DIR are used based on the nature of the anatomical region being considered. For gross tumor volumes (GTVs) and clinical target volumes (CTVs) that are considered mobile, a structure-guided DIR is utilized. For non-mobile regions, an elastic DIR is employed.

- -

- Propagation of GTVs and CTVs: Using the DIR results, the GTVs and CTVs from the planning CT are propagated or transferred to the CBCT, considering their mobility characteristics.

- -

- Propagation of Non-Influencer OARs and Synthetic CT Generation: Other organs at risk (OARs) that are not part of the influencer structures are propagated using the elastic DIR. Additionally, a synthetic CT is generated by deforming the planning CT into the CBCT geometry. This synthetic CT is used to provide density information for dose calculations in the treatment geometry.

- -

- Validation of Synthetic CT: The accuracy of the synthetic CT is validated on a patient-specific basis by visually checking the agreement between the synthetic CT and the acquired CBCT.

- -

- Generation of Adaptive Plan: A new treatment plan, referred to as the "adaptive plan," is generated based on a predefined "planning directive," optimized to the patient's anatomical changes on that specific day.

- -

- Reference Plan Recalculation: The original treatment plan (reference plan) is recalculated based on the daily anatomical changes observed, and it becomes the "scheduled plan."

- -

- Treatment Plan Selection: The radiation oncologist can choose between the "scheduled plan" and the "adaptive plan" for the treatment session.

- -

- Pre-treatment and Post-treatment QA: The plan selected for treatment receives quality assurance (QA) before treatment using calculation-based QA. After treatment, log file-based QA is performed using Mobius, another Varian Medical Systems product.

- Haut du formulaire

- -

- Resource Intensive: Implementing adaptive radiotherapy requires additional specialized equipment and software, as well as a skilled and experienced team to perform frequent imaging and replanning. This can lead to increased costs and a higher demand on department resources.

- -

- Time-consuming: The process of acquiring new images, analyzing them, and creating a revised treatment plan takes time. This can potentially prolong the overall treatment time, which may not be ideal for some patients.

- -

- Radiation exposure: The process of acquiring additional imaging for replanning may expose the patient to extra radiation, though modern imaging techniques aim to minimize this additional dose.

- -

- Limited Changes during Treatment: While adaptive radiotherapy allows for some modification during the treatment course, there are still limitations to what can be achieved. Major anatomical changes, such as significant tumor shrinkage or patient weight loss, may be challenging to address fully with adaptive planning alone.

- -

- Clinical Evidence and Guidelines: Although adaptive radiotherapy shows promise, the evidence supporting its benefits is still evolving. There may be varying protocols and guidelines for its use across different treatment centers.

- -

- Patient Selection: Not all patients may benefit from adaptive radiotherapy. The decision to use this technique depends on various factors, including the type and location of the tumor, the stage of the disease, and the overall health of the patient.Haut du formulaire

- 4.

- Clinical outcome Prediction

- -

- Precision Medicine: The ability to analyze a patient's specific tumor characteristics at a molecular level can lead to personalized treatment plans that are tailored to their unique genetic makeup, improving treatment efficacy and reducing side effects.

- -

- Predictive Models: Machine learning algorithms trained on large datasets can identify patterns and relationships between various omics data and treatment outcomes. These predictive models can help clinicians make more informed decisions about the best course of treatment for individual patients.

- -

- Early Detection of Treatment Response: By continuously monitoring omics data during treatment, it becomes possible to detect early signs of radiotherapy response or resistance. This early detection can allow for timely adjustments to the treatment plan to optimize outcomes.

- -

- Toxicity Prediction and Mitigation: Understanding the complex interactions among different omics data can also help predict and mitigate potential treatment-related side effects, improving patients' quality of life during and after radiotherapy.

- -

- Research and Drug Development: The analysis of big data in radiotherapy can also contribute to research and the development of new therapeutic strategies and drug targets

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 1201-1208. [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y.Y.M.; Wong, D.C.S.; Ting, D.S.W. The promise of artificial intelligence: a review of the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Br Med Bull. 2021, 139, 4-15. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, E.; Hosny, A.; Guthier, C.; et al. Artificial intelligence in radiation oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020, 17, 771–781. [CrossRef]

- Deborah Richards, Paul Formosa, Sarah Bankins, et al. Medical AI and human dignity: Contrasting perceptions of human and artificially intelligent (AI) decision making in diagnostic and medical resource allocation contexts. Computers in Human Behavior Volume 133, August 2022, 107296. [CrossRef]

- Mercieca, S.; Belderbos, J.S.A.; van Herk, M. Challenges in the target volume definition of lung cancer radiotherapy. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1983-1998. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Fong, A.; McVicar, N.; et al.Comparing deep learning-based auto-segmentation of organs at risk and clinical target volumes to expert inter-observer variability in radiotherapy planning. Radiother Oncol. 2020, 144, 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.; Pullen, H.; Welsh, C.; et al. Machine Learning for Auto-Segmentation in Radiotherapy Planning. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2022, 34, 74-88. [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M.V.; Lin, D.; Elguindi, S.; et al. Metrics to evaluate the performance of auto-segmentation for radiation treatment planning: A critical review. Radiother Oncol. 2021, 160, 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Hobbis, D.; Yu, N.Y.; Mund, K.W.; et al. First Report On Physician Assessment and Clinical Acceptability of Custom-Retrained Artificial Intelligence Models for Clinical Target Volume and Organs-at-Risk Auto-Delineation for Postprostatectomy Patients. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2023, 13, 351-362. [CrossRef]

- Sakashita, N.; Shirai, K.; Ueda, Y.; et al. Convolutional neural network-based automatic liver delineation on contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced CT images for radiotherapy planning. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020, 25, 981-986. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y-l Chen, L.; Shen, G.-z.; et al. Interobserver variations in the delineation of target volumes and organs at risk and their impact on dose distribution in intensity-modulated radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2018, 82, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lucido, J.J.; DeWees, T.A.; Leavitt, T.R.; et al. Validation of clinical acceptability of deep-learning-based automated segmentation of organs-at-risk for head-and-neck radiotherapy treatment planning. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1137803. [CrossRef]

- 13. Maria F. Chan,Alon Witztum, and Gilmer Valdes. Integration of AI and Machine Learning in Radiotherapy QA. Front. Artif. Intell., 29 September 2020.

- El Naqa, I.; Irrer, J.; Ritter, T.; et al. Machine learning for automated quality assurance in radiotherapy: a proof of principle using EPID data description. Med. Phys. 46, 1914–1921. [CrossRef]

- Tucker JNethertona b Carlos, E. et al. The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence within Radiation Oncology Treatment Planning. Oncology 2021, 99, 124–134 125. [CrossRef]

- Henkel, M.; Horn, T.; Leboutte, F.; et al. Initial experience with AI Pathway Companion: Evaluation of dashboard-enhanced clinical decision making in prostate cancer screening. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0271183. [CrossRef]

- RayStation: External beam treatment planning system. Medical Dosimetry 2018, 43, 168-176. [CrossRef]

- Pokharel S, Pacheco A, Tanner S. Assessment of efficacy in automated plan generation for Varian Ethos intelligent optimization engine. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022, 23, e13539. [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, A.; Houweling, A.C.; van Tienhoven, G.; et al. Dosimetric effects of anatomical changes during fractionated photon radiation therapy in pancreatic cancer patients. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017, 18, 142-151. [CrossRef]

- Sonke, J.J.; Aznar, M.; Rasch, C. Adaptive Radiotherapy for Anatomical Changes. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019, 29, 245-25. [CrossRef]

- Shelley, C.E.; Barraclough, L.H.; Nelder, C.L.; et al. Adaptive Radiotherapy in the Management of Cervical Cancer: Review of Strategies and Clinical Implementation. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2021, 33, 579-590. [CrossRef]

- Åström, L.M.; Behrens, C.P.; Calmels, L. ; et al. Online adaptive radiotherapy of urinary bladder cancer with full re-optimization to the anatomy of the day: Initial experience and dosimetric benefits. Radiother Oncol. 2022, 171, 37-42. [CrossRef]

- Weppler, S.; Quon, H.; Banerjee, R.; et al. Framework for the quantitative assessment of adaptive radiation therapy protocols. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018, 19, 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Green, O.L.; Henke, L.E.; Hugo, G.D. Practical Clinical Workflows for Online and Offline Adaptive Radiation Therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019, 29, 219-227. [CrossRef]

- 25. Hu, Y.; Byrne, M.; Archibald-Heeren, B.; et al. Validation of the preconfigured Varian Ethos Acuros XB Beam Model for treatment planning dose calculations: A dosimetric study. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2020, 21, 27-42. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Archibald-Heeren, B.; Hu, Y.T.; et al.Varian ethos online adaptive radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Early results of contouring accuracy, treatment plan quality, and treatment time. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022, 23, e13479. [CrossRef]

- Ahunbay, E.E.; Peng, C.; Holmes, S.; et al. Online adaptive replanning method for prostate radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010, 77, 1561-1572.

- Sibolt, P.; Andersson, L.M.; Calmels, L.; et al. Clinical implementation of artificial intelligence-driven cone-beam computed tomography-guided online adaptive radiotherapy in the pelvic region. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2021, 17, 1-7.

- Niraula, D.; Cui, S.; Pakela, J.; et al. Current status and future developments in predicting outcomes in radiation oncology. Br J Radiol. 2022, 95, 20220239. [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; van Stiphout, R.G.; Starmans, M.H.; et al. Predicting outcomes in radiation oncology--multifactorial decision support systems. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013, 10, 27-40. [CrossRef]

- El Naqa, I.; Kerns, S.L.; Coates, J.; et al. Radiogenomics and radiotherapy response modeling. Phys Med Biol. 2017, 62, R179-R206. [CrossRef]

- Alkhadar, H.; Macluskey, M.; White, S.; et al. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for the prediction of five-year survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021, 50, 378–84.

- Isaksson, L.J.; Pepa, M.; Zaffaroni, M.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Models for Prediction of Toxicity Outcomes in Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 10, 790. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).