Submitted:

13 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. GC-MS characterization of Tamanu oil

2.2. In silico studies -Molecular modeling

2.3. Formulation of Bigels

2.4. Evaluation of Bigel

2.4.1. pH

2.4.2. Viscosity

2.4.3. Spreadability

2.4.4. SEM analysis

2.5. In vivo studies

2.5.1. Acute dermal irritation studies

2.5.2. In vivo wound healing studies

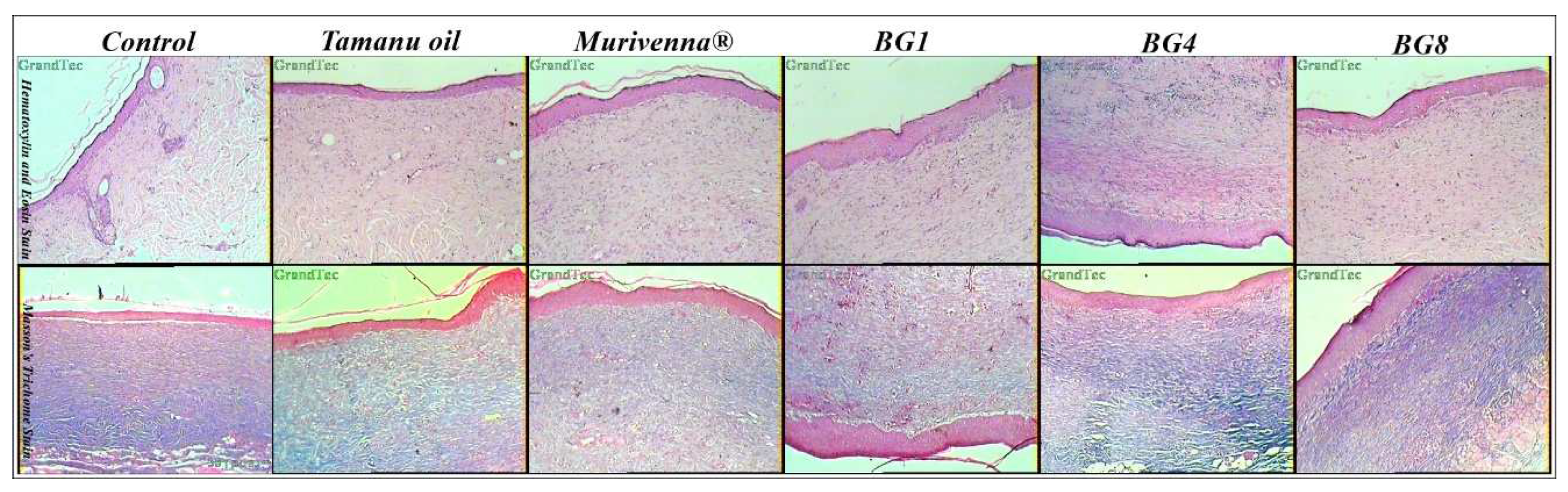

2.6. Histopathological Studies

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Materials

3.2. GC-MS characterization of Tamanu oil

3.3. In silico studies

3.3.1. Preparation of ligand and selection of Protein

3.3.2. Preparation of Protein

3.3.3. Molecular modeling studies

3.4. Formulation of Bigels

3.5. Evaluation of Bigels

3.5.1. Organoleptic evaluation

3.5.2. pH

3.5.3. Spreadability

3.5.4. Viscosity

3.5.5. Scanning Electron Microscopic analysis

3.6. In Vivo Studies

3.6.1. Acute dermal irritation studies

3.6.2. In vivo wound healing studies

3.7. Histopathological Studies:

3.8. Statistical analysis

4. CONCLUSION

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L. A. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. Journal of Dental Research 2010, 89(3), 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonova, V.; Peneva, P.; Georgiev, G. V.; Toncheva, V. T.; Apostolova, E.; Peychev, Z.; Dimitrova, S.; Katsarova, M.; Petrova, N.; Kassarova, M. Ketoprofen-Loaded Polymer Carriers in Bigel Formulation: An Approach to Enhancing Drug Photostability in Topical Application Forms. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2017, Volume 12, 6221–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolz, L.-P.; Griffith, M.; Finnerty, C. C.; Kasper, C. Skin Regeneration, Repair, and Reconstruction. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Lin, C.; Lin, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Xiang, L.; Di-Jiong, G.; Luo, X.; Zhang, G.; Fu, X.; Bellusci, S.; Li, X.; Xiao, J. The Anti-Scar Effects of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor on the Wound Repair In Vitro and In Vivo. PLOS ONE 2013, 8(4), e59966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, H.; Patel, S.; Pastar, I. The Role of TGFΒ Signaling in Wound Epithelialization. Advances in Wound Care 2014, 3(7), 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, A.-I.; Grumezescu, A. M.; Hermenean, A.; Andronescu, E.; Vasile, B. S. Scar-Free Healing: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2020, 10(11), 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, M. K.; Otero-Viñas, M.; Falanga, V. Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β) Isoforms in Wound Healing and Fibrosis. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2016, 24(2), 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, A. C.; Meadows, T. T. Tamanu (Calophyllum Inophyllum) - the African, Asian, Polynesian and Pacific Panacea. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 2002, 24(6), 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassien, M.; Mercier, A.; Thétiot-Laurent, S.; Culcasi, M.; Ricquebourg, E.; Asteian, A.; Herbette, G.; Bianchini, J.-P.; Raharivelomanana, P.; Pietri, S. Improving the Antioxidant Properties of Calophyllum Inophyllum Seed Oil from French Polynesia: Development and Biological Applications of Resinous Ethanol-Soluble Extracts. Antioxidants 2021, 10(2), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginigini, J.; Lecellier, G.; Nicolas, M.; Nour, M.; Hnawia, E.; Lebouvier, N.; Herbette, G.; Lockhart, P. J.; Raharivelomanana, P. Chemodiversity ofCalophyllum InophyllumL. Oil Bioactive Components Related to Their Specific Geographical Distribution in the South Pacific Region. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J. S.; Shrivastava, A.; Khanna, A.; Bhatia, G.; Awasthi, S. K.; Narender, T. Antidyslipidemic and Antioxidant Activity of the Constituents Isolated from the Leaves of Calophyllum Inophyllum. Phytomedicine 2012, 19(14), 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pribowo, A.; Girish, J.; Gustiananda, M.; Nandhira, R. G.; Hartrianti, P. Potential of Tamanu (Calophyllum Inophyllum) Oil for Atopic Dermatitis Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saki, E.; Murthy, V.; Khandanlou, R.; Wang, H.; Wapling, J.; Weir, R. Optimisation of Calophyllum Inophyllum Seed Oil Nanoemulsion as a Potential Wound Healing Agent. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 2022, 22(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Ekambaram, S.; Dhanam, T. In Vivo Antiarthritic Activity of the Ethanol Extracts of Stem Bark and Seeds of Calophyllum Inophyllum in Freund’s Complete Adjuvant Induced Arthritis. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, S. S.; Gur, T.; Terzi, N. K.; Dogan, B. Evaluation of the Cutaneous Wound Healing Potential of Tamanu Oil in Wounds Induced in Rats. Journal of Wound Care 2021, 30(Sup9a), Vi–Vx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léguillier, T.; Lecsö-Bornet, M.; Lemus, C.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D.; Lebouvier, N.; Hnawia, E.; Nour, M.; Aalbersberg, W. G. L.; Ghazi, K.; Raharivelomanana, P.; Rat, P. The Wound Healing and Antibacterial Activity of Five Ethnomedical Calophyllum Inophyllum Oils: An Alternative Therapeutic Strategy to Treat Infected Wounds. HAL (Le Centre Pour La Communication Scientifique Directe), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Chen, Z.-F.; Chiou, W.-F.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-C. Calophyllolide Content in Calophyllum Inophyllum at Different Stages of Maturity and Its Osteogenic Activity. Molecules 2015, 20(7), 12314–12327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-L.; Truong, C.-T.; Nguyen, B. C. Q.; Van Vo, T.-N.; Dao, T.-T.; Nguyen, V.-D.; Trinh, D.-T. T.; Huynh, H. K.; Bui, C.-B. Anti-Inflammatory and Wound Healing Activities of Calophyllolide Isolated from Calophyllum Inophyllum Linn. PLOS ONE 2017, 12(10), e0185674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. C.; Yu, L.; Chiang, J.-H.; Liu, F. C.; Lin, W.-H.; Chang, S.-Y.; Lin, W.; Wu, C. H.; Weng, J. R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Calophyllum Inophyllum L. in RAW264.7 Cells. Oncology Reports 2012, 28(3), 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansel, J.-L.; Lupo, E.; Mijouin, L.; Guillot, S.; Butaud, J.-F.; Ho, R.; Lecellier, G.; Raharivelomanana, P.; Pichon, C. Biological Activity of Polynesian Calophyllum Inophyllum Oil Extract on Human Skin Cells. Planta Medica 2016, 82(11/12), 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Farooq, U.; Gabriele, D.; Marangoni, A. G.; Lupi, F. R. Bigels and Multi-Component Organogels: An Overview from Rheological Perspective. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 111, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltuonytė, G.; Eisinaitė, V.; Kazernavičiūtė, R.; Vinauskienė, R.; Jasutienė, I.; Leskauskaitė, D. Novel Formulation of Bigel-Based Vegetable Oil Spreads Enriched with Lingonberry Pomace. Foods 2022, 11(15), 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Illana, A.; Notario-Pérez, F.; Cazorla-Luna, R.; Ruiz-Caro, R.; Bonferoni, M. C.; Tamayo, A.; Veiga, M.D. Bigels as Drug Delivery Systems: From Their Components to Their Applications. Drug Discovery Today 2022, 27(4), 1008–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthy, P.; Patil, S. B. A Clinical Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Murivenna Application on Episiotomy Wound. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrated Medical Sciences 2020, 5(05), 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepsibah, P.T. , Rosamma, M.P., Prasad, N.B., Kumar, P.S. Standardisation of murivenna and hemajeevanti taila. Ancient science of life 1993, 12, 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan, A.; Mani, M. P.; Jaganathan, S. K.; Rajasekar, R.; Mani, M. P. Formation of Functional Nanofibrous Electrospun Polyurethane and Murivenna Oil with Improved Haemocompatibility for Wound Healing. Polymer Testing 2017, 61, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoigawa, M.; Ito, C.; Tan, H. T. W.; Kuchide, M.; Tokuda, H.; Nishino, H.; Furukawa, H. Cancer Chemopreventive Agents, 4-Phenylcoumarins from Calophyllum Inophyllum. Cancer Letters 2001, 169(1), 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan R, Dhachinamoorthi D, Senthilkumar K, Thamizhvanan K. Antimicrobial activity of various extracts from various parts of Calophyllum inophyllum L. J Appl Pharm Sci 2011, 1(3), 12.

- Creagh, T.; Ruckle, J.; Tolbert, D. T.; Giltner, J.; Eiznhamer, D. A.; Dutta, B.; Flavin, M. T.; Xu, Z. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single Doses of (+)-Calanolide A, a Novel, Naturally Occurring Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor, in Healthy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Negative Human Subjects. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2001, 45(5), 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saechan, C.; Kaewsrichan, J.; Leelakanok, N.; Petchsomrit, A. Antioxidant in Cosmeceutical Products Containing Calophyllum Inophyllum Oil. OCL 2021, 28, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. L.; Truong, C.T.; Nguyen, B. C. Q.; Van Vo, T.N.; Dao, T.T.; Nguyen, V.D.; Trinh, D.T. T.; Huynh, H.K.; Bui, C.B. Anti-Inflammatory and Wound Healing Activities of Calophyllolide Isolated from Calophyllum Inophyllum Linn. PLOS ONE 2017, 12(10), e0185674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L. A.; Mitchell, T.; Brinckerhoff, C. E. Transforming Growth Factor β Inhibitory Element in the Rabbit Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (Collagenase-1) Gene Functions as a Repressor of Constitutive Transcription. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (N) 2000, 1490(3), 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakyari, M.; Farrokhi, A.; Maharlooei, M. K.; Ghahary, A. Critical Role of Transforming Growth Factor Beta in Different Phases of Wound Healing. Advances in Wound Care 2013, 2(5), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Anjum, F.; Shafie, A.; Ashour, A. A.; Almalki, A. A.; Alqarni, A. A.; Banjer, H. J.; Almaghrabi, S. A.; He, S.; Xu, N. Identifying Promising GSK3β Inhibitors for Cancer Management: A Computational Pipeline Combining Virtual Screening and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Frontiers in Chemistry 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C. Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, B.; Zhang, P. In Silico ADME and Toxicity Prediction of Ceftazidime and Its Impurities. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmeen, J. B.; Mahomoodally, F.; Zengin, G.; Maggi, F. Essential Oils as Natural Sources of Fragrance Compounds for Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26(3), 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukić, M.; Pantelić, I.; Savić, S. Towards Optimal PH of the Skin and Topical Formulations: From the Current State of the Art to Tailored Products. Cosmetics 2021, 8(3), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, D.S. Development, Characterization, and In vitro Evaluation of Aceclofenac Emulgel. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Szulc-Musioł, B.; Dolińska, B.; Kołodziejska, J.; Ryszka, F. Influence of Plasma on the Physical Properties of Ointments with Quercetin. Acta Pharmaceutica 2017, 67(4), 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomuanya, M. O.; Hameedat, A. T.; Akang, E. E. U.; Ekama, S. O.; Silva, B. O.; Akanmu, A. S. Development and Evaluation of Mucoadhesive Bigel Containing Tenofovir and Maraviroc for HIV Prophylaxis. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD, 2015. Test No. 404: Acute Dermal Irritation/Corrosion.

- Nagar, H.; Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, R.; Kurmi, M. L.; Chandel, H. S.; Ranawat, M. S. Pharmacological Investigation of the Wound Healing Activity of Cestrum Nocturnum (L.) Ointment in Wistar Albino Rats. Journal of Pharmaceutics 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Mohanty, M.; Fernandez, A. C.; Mohanan, P. V.; Jayakrishnan, A. Evaluation of the Effect of Incorporation of Dibutyryl Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate in an in Situ-Forming Hydrogel Wound Dressing Based on Oxidized Alginate and Gelatin. Biomaterials 2006, 27(8), 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellur, S.; Pavadai, P.; Babkiewicz, E.; Ram Kumar Pandian, S.; Maszczyk, P.; Kunjiappan, S. An In Silico Molecular Modelling-Based Prediction of Potential Keap1 Inhibitors from Hemidesmus indicus (L.) R.Br. against Oxidative-Stress-Induced Diseases. Molecules 2023, 28, 4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabale, V.; Kunjwani, H. K.; Sabale, P. M. Formulation and in Vitro Evaluation of the Topical Antiageing Preparation of the Fruit of Benincasa Hispida. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine 2011, 2(3), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sl.no. | Compounds | Component RT (min) |

Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calanolide A | 31.03 | C22H26O5 |

| 2 | Calophyllolide | 33.52 | C26H24O5 |

| 3 | Inophyllum C | 24.91 | C25H22O5 |

| 4 | Oleic acid | 26.16 | C18H34O2 |

| 5 | Linoleic acid | 26.16 | C18H32O2 |

| 6 | Palmitic acid | 23.27 | C16H32O2 |

| 7 | Stearic acid | 26.38 | C18H36O2 |

| 8 | 4-Norlanosta-17(20),24-diene-11,16-diol-21-oic acid, 3-oxo-16,21-lactone | 29.66 | C29H42O4 |

| 9 | Hyenic acid /Pentacosanoic acid | 25.28 | C25H50O2 |

| Compounds | Docking score | Residues | Amino Acid | Distance (Å) | Type of Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calophyllolide | -8.6 | 219A | VAL | 3.67 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.7 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 337A | LYS | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 287A | SER | 2.3 | Hydrogen | ||

| Inophyllum C | -11.3 | 219A | VAL | 3.59 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.85 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 230A | ALA | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.85 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.4 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.86 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.7 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 350A | ALA | 3.69 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.41 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 283A | HIS | 2.47 | Hydrogen | ||

| Calanolide A | -9.8 | 211A | ILE | 3.65 | Hydrophobic |

| 211A | ILE | 3.56 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 219A | VAL | 3.95 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.72 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.45 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.41 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.77 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.88 | Hydrogen | ||

| 283A | HIS | 2.31 | Hydrogen | ||

| Oleic acid | -5.3 | 211A | ILE | 3.84 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.81 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 219A | VAL | 3.68 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.88 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.36 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 350A | ALA | 3.62 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.91 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.21 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.56 | Hydrogen | ||

| Linoleic acid | -6.4 | 211A | ILE | 3.62 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.52 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 219A | VAL | 3.87 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.77 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.42 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 249A | TYR | 3.67 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 249A | TYR | 3.77 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 262A | PHE | 3.77 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.51 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 280A | SER | 3.35 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 3.25 | Hydrogen | ||

| 283A | HIS | 1.87 | Hydrogen | ||

| Palmitic acid | -5.9 | 232A | LYS | 3.77 | Hydrophobic |

| 249A | TYR | 3.74 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 249A | TYR | 3.71 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 262A | PHE | 3.45 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 278A | LEU | 3.58 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.58 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 283A | HIS | 2.9 | Hydrogen | ||

| Stearic acid | -5.6 | 230A | ALA | 3.63 | Hydrophobic |

| 232A | LYS | 3.6 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.61 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 230A | ALA | 3.06 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.54 | Hydrogen | ||

| 4-Norlanosta-17(20),24-diene-11,16-diol-21-oic acid, 3-oxo-16,21-lactone | -11.1 | 211A | ILE | 3.56 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.85 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 230A | ALA | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.98 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 282A | TYR | 3.87 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 337A | LYS | 3.73 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.86 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.15 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 350A | ALA | 3.77 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.87 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 287A | SER | 3.08 | Hydrogen | ||

| 232A | LYS | 4.09 | Salt Bridge | ||

| Hyenic acid | -5 | 211A | ILE | 3.34 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.59 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 219A | VAL | 3.32 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.63 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 260A | LEU | 3.72 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 337A | LYS | 3.99 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.98 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 350A | ALA | 3.81 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.72 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 231A | VAL | 3.29 | Hydrogen | ||

| Bleomycin | -8.3 | 211A | ILE | 3.43 | Hydrophobic |

| 219A | VAL | 3.98 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 340A | LEU | 3.86 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 351A | ASP | 3.71 | Hydrophobic | ||

| 232A | LYS | 3.16 | Hydrogen | ||

| 245A | GLU | 2.02 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.32 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.51 | Hydrogen | ||

| 280A | SER | 2.45 | Hydrogen | ||

| 285A | HIS | 3.01 | Hydrogen | ||

| 287A | SER | 3.33 | Hydrogen | ||

| 290A | ASP | 2.29 | Hydrogen | ||

| 290A | ASP | 2.22 | Hydrogen | ||

| 290A | ASP | 2.63 | Hydrogen | ||

| 290A | ASP | 2.75 | Hydrogen | ||

| 290A | ASP | 2.7 | Hydrogen | ||

| 335A | LYS | 3.05 | Hydrogen | ||

| 337A | LYS | 2.59 | Hydrogen | ||

| 337A | LYS | 2.2 | Hydrogen | ||

| 338A | ASN | 2.78 | Hydrogen | ||

| 435A | ASP | 2.84 | Hydrogen | ||

| 289A | PHE | 4.81 | π-Stacking | ||

| 337A | LYS | 5.33 | Salt Bridge |

| Parameters | BG1 | BG2 | BG3 | BG4 | BG5 | BG6 | BG7 | BG8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.82±0.05 | 5.96±0.06 | 5.92±0.12 | 6.04±0.07 | 5.96±0.17 | 5.58±0.03 | 5.62±0.13 | 5.76±0.10 |

| Spreadability (cm) | 6.50±0.36 | 6.10±0.26 | 5.93±0.25 | 5.63±0.30 | 5.46±0.40 | 5.36±0.05 | 5.30±0.10 | 5.26±0.15 |

| Viscosity (cps) | 220.4±0.96 | 238.9±0.85 | 252.9±0.65 | 273.8±0.05 | 313.0±0.15 | 337.4±0.25 | 378.4±0.05 | 391.5±0.28 |

| Group | Control | Tamanu oil | Murivenna® | BG1 | BG4 | BG8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 0.573±0.0049 | 0.538±0.0047** | 0.555 ±0.0042ns | 0.561±0.0094ns | 0.511±0.0060** | 0.505±0.0042** |

| Day 6 | 0.470±0.0057 | 0.460±0.0051ns | 0.451±0.0047* | 0.463 ±0.0042ns | 0.415±0.00428** | 0.405±0.0042** |

| Day 9 | 0.418±0.0094 | 0.350±0.0036** | 0.358±0.0095** | 0.380±0.0057** | 0.273±0.0066** | 0.248±0.0095** |

| Day 12 | 0.251±0.0104 | 0.112±0.0107** | 0.098±0.0047** | 0.1283±0.0060** | 0.0833±0.0066** | 0.00±0.00** |

| Day 15 | 0.083±0.0025 | 0.00±0.00** | 0.00±0.00** | 0.00±0.00** | 0.00±0.00** | 0.00±0.00** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).