Preprint

Review

Role of Substance P and Neurokinin-1 Receptor System in Thyroid Cancer: New Targets for Cancer Treatment

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

Abstract

In recent years, numerous approaches have been developed to comprehend the molecular altera-tions underlying thyroid cancer (TC) oncogenesis and explore novel therapeutic strategies for TC. It is now well established that the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) is overexpressed in cancer cells and that NK-1R is essential for viability of cancer cells. The binding of substance P (SP) to NK-1R in neoplastic cells plays a pivotal role in cancer progression by promoting neoplastic cell growth, protecting tumour cells from apoptosis, triggering invasion and metastasis through enhanced migration of cancer cells, and stimulating endothelial cell proliferation for tumour angiogenesis. Remarkably, all types of human TC (papillary, follicular, medullary, anaplastic), as well as met-astatic lesions, exhibit overexpression of SP and NK-1R compared to the normal thyroid gland. TC cells synthesize and release SP, which exerts its multiple functions through autocrine, para-crine, intracrine, and neuroendocrine processes, including the regulation of tumour burden. Con-sequently, the secretion of SP from TC results in increased SP levels in plasma, which are signifi-cantly higher in TC patients compared to controls. Additionally, NK-1R antagonists have demonstrated a dose-dependent antitumour action. They impair cancer cell proliferation on one side and induce apoptosis of tumour cells on the other side. Furthermore, it has been demonstrat-ed that NK-1R antagonists inhibit neoplastic cell migration, thereby impairing both invasiveness and metastatic abilities, as well as angiogenesis. Given the consistent overexpression of NK-1R in all types of TC, targeting this receptor represents a promising therapeutic approach for TC. Therefore, NK-1R antagonists, such as the drug aprepitant, may represent novel drugs for TC treatment.

Keywords:

Neurokin-1 receptor

; substance P

; tachykinin

; thyroid gland

; thyroid cancer

1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignant neoplasm [1]. Differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) encompasses papillary and follicular variants, accounting for over 90% of all TC cases, ranging from indolent localized papillary carcinomas to aggressive anaplastic neoplasms [2]. DTC is believed to originate from epithelial cells and comprises various subtypes, including papillary (PTC, 80%), follicular (FTC, 11%), and rarer variants such as poorly differentiated TC (PDTC), Hürthle cell TC, insular carcinoma, follicular variant of PTC, and tall cell carcinoma [3]. Patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis have a higher risk of developing DTC. Medullary TC (MTC), derived from calcitonin-producing parafollicular cells (C cells), represents 5-10% of all TCs [4], while anaplastic TC (ATC) is an extremely aggressive neoplasm, observed in only 2% of patients, with a survival rate of less than six months. Lymphomas and sarcomas are rare subtypes reported in the thyroid gland [5]. Approximately 15% of DTC patients develop distant metastases, with half of them presenting at the initial stages of the disease [6]. In recent years, TC incidence has been rapidly increasing worldwide, predominantly among women, and PTC is projected to become the third most common cancer in women [7].

Considerable efforts have been devoted to investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying TC oncogenesis in the past decade [8]. Current guidelines recommend surgery, typically full thyroidectomy, for TC patients, with adjuvant radioiodine treatment (131I) for those at high risk of recurrence. Recurrences are managed surgically, along with radioactive iodine and radiotherapy [9]. As standard therapies are associated with significant morbidity, exploring new therapeutic strategies is crucial to improve prognosis and quality of life in TC patients. Neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) antagonists have shown potential in TC treatment, as the substance P (SP)/NK-1R system is expressed in human TC.

The TAC1 gene encodes the SP peptide, which belongs to the tachykinin family, including hemokinin-1 (HK-1), neurokinin A (NKA), and NKB. Tachykinins exert various biological functions upon binding to NK-1R, NK-2R, and/or NK-3R. NK-1R, encoded by the TACR1 gene, exhibits preferential affinity for SP/HK-1, while NKA and NKB preferentially bind to NK-2R and NK-3R, respectively [10,11]. NK-1R is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family and consists of three intracellular and three extracellular loops, with a possible additional fourth loop [10]. Two isoforms of NK-1R exist: full-length and truncated. The truncated isoform, lacking the last 96 amino acids of the C-terminus, is overexpressed in neoplastic cells and remains continuously present in the cell membrane without internalization [12,13,14]. SP is widely distributed throughout the body and regulates numerous biological functions, including pain, neurogenic inflammation, and mitogenesis.

NK-1R is overexpressed in neoplastic cells, with truncated NK-1R being more prevalent than the full-length molecule [13,14]. NK-1R has been reported to be essential for cancer cells [15], as SP binding to NK-1R promotes cancer cell proliferation, suppresses apoptosis, activates angiogenesis, and enhances the migratory capacity of neoplastic cells, thereby increasing invasiveness and metastatic potential [16]. Several studies have demonstrated that NK-1R antagonists counteract these SP-mediated effects, inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis in human tumour cells [13,16,17,18,19]. Considering the significance of the SP/NK-1R system in cancer progression, NK-1R represents a potential target for cancer treatment, with NK-1R antagonists being considered as broad-spectrum antineoplastic agents [20]. In light of the overexpression of the SP/NK-1R system in TC, we propose the use of NK-1R antagonists in TC patients. Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to review the existing data on SP and NK-1R in TC and provide a basis for future studies that could justify the utilization of NK-1R antagonists in TC patients [21,22].

2. Substance P and Neurokinin-1 Receptor in Thyroid Cancer

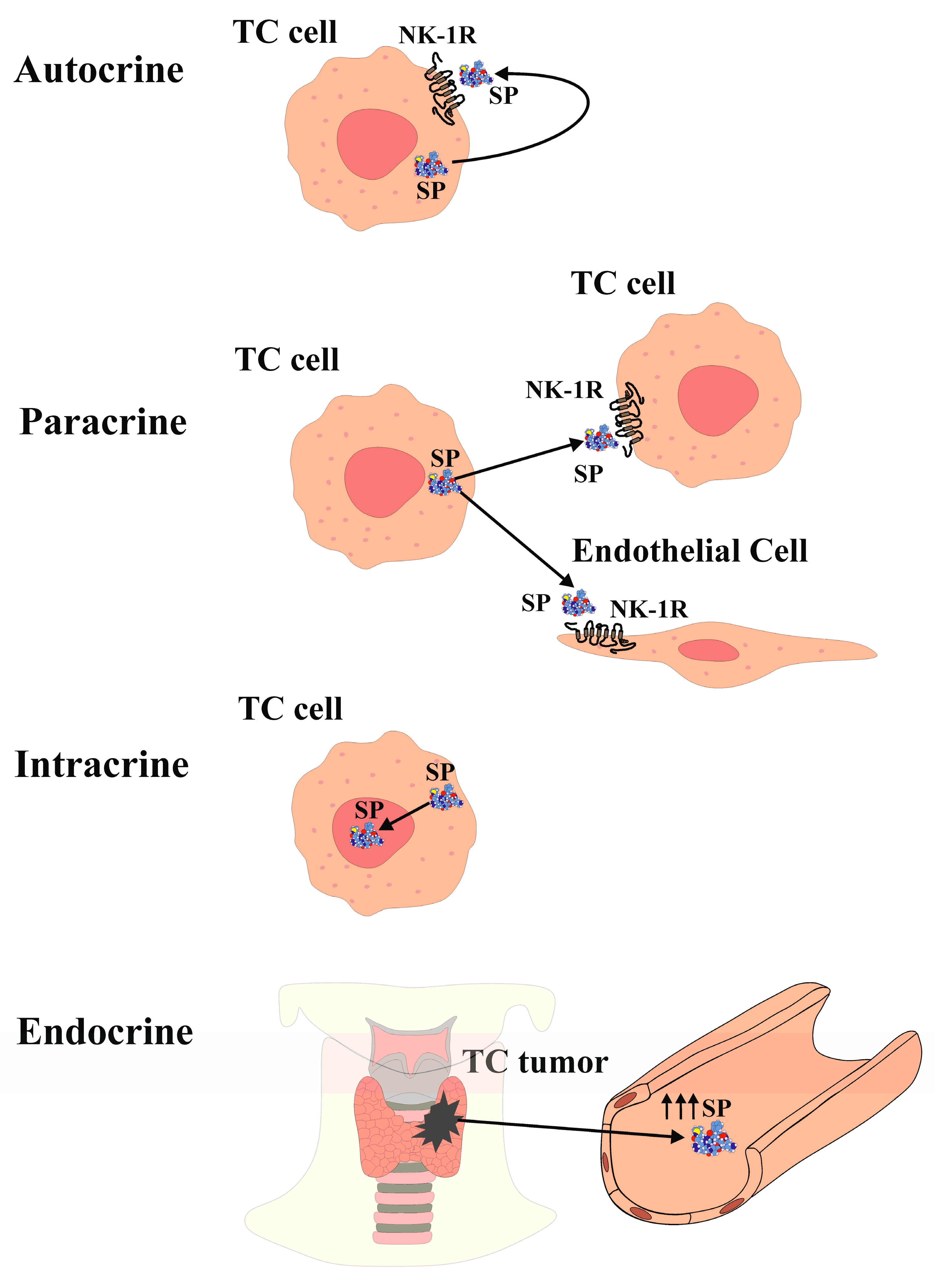

The expression of SP and NK-1R in the thyroid gland and thyroid cancer (TC) has been investigated for over 40 years. Previous studies reported elevated blood levels of SP in a patient with medullary TC [23]. Immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrated SP expression in only one out of twenty-seven medullary TC cases in one study [24], while another study detected NK-1R expression in 10 out of 12 medullary TC cases [25]. However, recent research has demonstrated the presence of both SP and NK-1R in normal thyroid tissue as well as in samples representing the four main types of TC (anaplastic, follicular, medullary, and papillary) [21]. Both SP and NK-1R were found in all TC and normal thyroid samples examined, and their expression was higher in TC tissue compared to healthy thyroid tissue. Notably, both SP and NK-1R were expressed in all normal and medullary TC samples [21]. Furthermore, a case-control study involving 31 healthy volunteers and 31 TC patients reported higher plasma levels of SP in the tumour group compared to the control group, along with stronger expression of NK-1R in TC specimens compared to the surrounding normal tissue [26]. These refined immunodetection techniques have provided substantial evidence for the widespread presence of both NK-1R and SP, with elevated SP serum levels observed in TC patients compared to controls. Moreover, SP and NK-1R are expressed in the thyroid gland and are overexpressed in all types of TC [21,26]. Additionally, the presence of SP/NK-1R in the nucleus and cytoplasm of TC follicular cells aligns with findings in various human malignant neoplasms, such as keratocystic odontogenic tumours, gastric carcinoma, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, small and non-small lung cancer, melanoma, and breast cancer [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. SP has been detected within the nucleus of endothelial cells in FTC samples, as well as in the nucleus of endothelial cells and myocytes of fetal blood vessels, decidua, and trophoblast [36]. Furthermore, SP and NK-1R have been identified in the nucleus of stem cells [37]. These findings collectively demonstrate the presence of the SP/NK-1R system within the nucleus of TC cells, suggesting a role in regulating nuclear activity in an epigenetic manner, thereby influencing cell behaviour [21,37]. The SP/NK-1R system in the limbic system of the central nervous system has also been implicated in regulating emotional behaviour [38]. Furthermore, SP can be considered an epigenetic factor that modulates gene expression in TC cells, affecting processes such as cellular differentiation, cell cycle progression, angiogenesis, inflammation, and apoptosis, through interactions with various transcription factors and proto-oncogenes [39,40,41]. SP is observed in the cytoplasm of both normal and neoplastic TC follicular cells, indicating potential autocrine, paracrine, intracrine, and/or endocrine actions (Figure 1). Notably, NK-1R is present in the colloid of TC samples but not in normal thyroid tissue, possibly related to the higher turnover of neoplastic cells in TC compared to normal thyroid tissue [21].

At nanomolar concentrations, SP induces mitogenesis in many human neoplastic cells, which may explain the overexpression of its receptor [42,43,44,45,46]. Through NK-1R, SP activates various molecules in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, leading to the translocation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) into the nucleus, thereby promoting cell proliferation. The activation of the MAPK cascade requires the presence of a functional epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase domain [47]. Another potential pathophysiological effect of SP on tumour cells is its anti-apoptotic effect, preventing tumour cell death. SP binding to NK-1R enhances the phosphorylation and activity of protein kinase B (Akt), exerting an anti-apoptotic effect [48].

The release of SP from TC cells suggests both, an autocrine action (Figure 1) SP binding to NK-1R that is overexpressed in TC cells and induces TC cells proliferation, and a paracrine action (Figure 1) of the peptide on NK-1R-expressing endothelial cells, potentially inducing proliferation and promoting neovascularization within and around the tumour, thereby enhancing TC growth [16,49]. Furthermore, NK-1R is found in blood vessels, and its expression increases during neo-angiogenesis [25].

The term "intracrine" refers to molecules that act within a cell to regulate intracellular events [50]. Peptide/protein hormones that exhibit intracellular function are also known as "intracrine." Given the localization of SP in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus of TC cells [21], SP is believed to exhibit intracrine (nucleocrine) function in TC cells (Figure 1). While peptides typically act as endocrine, autocrine, or paracrine by binding to receptors on the cell surface, SP in TC cells also acts through intracrine mechanisms. Notably, SP is expressed within the nucleus of TC cells, whereas NK-1R expression in the nucleus is exceptional. This raises the question whether SP directly binds to the DNA, in TC cells. It is known that TATA-box binding protein (TBP) binds to the minor groove of DNA at the TATA box sequence, producing a large-scale deformation in DNA and initiating transcription. Moreover, binding of small molecules or proteins to DNA often leads to DNA deformation, and that DNA folding is facilitated by the projection of two phenylalanine residues from the TPB into the minor groove [51]. Interestingly, SP contains two phenylalanine residues at its C-terminus [52].

Furthermore, SP can be released into the bloodstream from the TC mass, suggesting an endocrine action (Figure 1), leading to elevated SP plasma levels. This is supported by the observation of high SP levels in the plasma of a patient with medullary TC [53]. Additionally, SP serum levels were higher in TC patients compared to healthy volunteers [26]. The elevated blood levels of SP may contribute to the development of paraneoplastic syndromes, such as thrombosis, pruritus, emotional stress, and malnutrition. Platelets express NK-1R, and SP can induce thrombosis, whereas NK-1R antagonists have been shown to reduce thrombus formation [54]. Anxiety and depression have also been associated with high plasma SP levels, suggesting that SP release from TC masses may contribute to depression by establishing a cross-talk between the limbic system (emotional stress) and TC, creating a reciprocal relationship [38]. Furthermore, elevated SP levels may be implicated in pruritus, as SP itself can induce pruritus, and NK-1R antagonists have shown efficacy in alleviating this symptom [55].

In summary, the presence of SP and NK-1R in TC cells suggests their involvement in autocrine, paracrine, intracrine, and endocrine mechanisms (Figure 1). The release of SP may induce mitogenesis in TC cells, enhance an antiapoptotic effect, promote TC angiogenesis, and stimulate TC cell migration, thereby facilitating invasion and metastasis. Moreover, SP levels are elevated in TC patients, NK-1R is overexpressed in TC cells and NK-1R is essential for the viability of TC cells.

3. NK-1R Antagonists as Novel Therapeutic Agents in Thyroid Cancer Treatment

NK-1R antagonists are a group of specific nonpeptide molecules that share similar stereochemical features and are resistant to degradation by peptidases, making them suitable candidates for thyroid cancer (TC) therapy.

3.1. Therapeutic Effect of NK-1R Antagonists as Anti-proliferative and Pro-apoptotic Agents in TC

Currently, there are four NK-1R antagonists, namely L-733,060, L-732,138, CP-96,345, and aprepitant drug (approved for chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting (CINV) in humans), which have demonstrated activity against cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [56]. These NK-1R antagonists inhibit neoplastic cells proliferation [13,18,19] and induce apoptosis in several and different tumour cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner [13,16,17]. Studies have shown that L-733,060 and aprepitant drug increase the occurrence of apoptotic DNA features, leading to the cleavage of caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in hepatoblastoma and glioma cell lines [13,48]. L-733,060 also enhances apoptosis, inhibits basal kinase activity of Akt, and induces similar effects on caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in glioma cells [48].

3.2. Therapeutic Effect of NK-1R Antagonists as Anti-angiogenic Drugs in TC

Angiogenesis plays a crucial role in cancer progression, as solid tumours require an efficient blood supply. NK-1R overexpression has been associated with angiogenesis, and NK-1R has been detected in intra- and perineoplastic blood vessels in various tumours [25]. SP directly stimulates angiogenesis by inducing endothelial cells proliferation. However, specific NK-1R antagonists can block SP-induced angiogenesis [25,47]. In a xenograft mouse model of hepatoblastoma, aprepitant administration at a dose of 80 mg/kg/day for 24 days resulted in a significant reduction in tumour growth and vascularized area within the tumour [13]. Furthermore, aprepitant has been reported to decrease vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, a well-known marker of angiogenesis, in osteosarcoma cells [57]. These findings strongly support the potential use of aprepitant in TC to reduce or inhibit tumour angiogenesis.

3.3. Therapeutic Effect of NK-1R Antagonists in Counteracting the Warburg Effect in Cancer

Neoplastic cells primarily rely on a high rate of glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect [58]. Studies have shown that SP promotes glycogen breakdown and increases intracellular calcium concentration in glioblastoma cells overexpressing NK-1R. However, the NK-1R antagonist CP-96,345 has been found to counteract these effects [59]. It has been suggested that the glycolytic function is directly related to the number of NK-1R receptors expressed in each cell, with tumour cells exhibiting higher expression levels and increased glycolytic rates [16]. This therapeutic effect of NK-1R antagonists is particularly important, as there are currently no available drugs that specifically counteract the Warburg effect.

3.4. Therapeutic Effect of NK-1R Antagonists as Anti-Metastatic Agents in Cancer

Despite favorable survival rates in most TC patients, those with local invasion and metastasis often do not respond well to standard treatments and have a poor prognosis [60]. Tumour cells migration is critical for invasiveness and metastatic potential, with metastasis being the leading cause of cancer-related deaths [61]. SP, upon binding to NK-1R, induces changes in cancer cell shape, including blebbing, which is essential for cancer cell spreading and infiltration [17]. Interestingly, U373MG astrocytoma tumour cells display significantly more rapid and transient membrane blebbing compared to non-tumour cells [62]. Moreover, SP has been shown to increase the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) and vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C), both of which are associated with vascular invasion and lymphatic metastasis. However, NK-1R antagonists L-733,060 and L-732,138 inhibit the expression of both VEGF-C and MMP-9 in endometrial adenocarcinoma cells, suggesting potential reduction in invasiveness and metastatic capabilities [63]. Furthermore, SP promotes migration and induces the expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF-A, and VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1) in esophageal cancer cells, whereas aprepitant counteracts these effects [64]. The anti-metastatic effect of aprepitant in TC could be attributed to its modulation of NF-κB and subsequent downregulation of its target genes, including VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGFR1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 [57,63,64].

3.5. Safety and Efficacy of NK-1R Antagonists in Thyroid Cancer Therapy

The reported side effects of aprepitant/fosaprepitant are minimal, with constipation, fatigue, headache, anorexia, hiccups, and diarrhoea being the most common adverse events (with an incidence higher than 10%) [64,65]. In contrast, conventional cytostatic drugs used in chemotherapy are non-specific and associated with severe side effects, including neutropenic fever. Aprepitant, on the other hand, has multiple therapeutic effects in clinical practice, such as antinausea and vomiting, anti-pruritic, cough suppressant, and antidepressant effects [17,38,55,66]. Therefore, aprepitant has a much higher safety profile compared to cytostatic drugs, aligning with the fundamental principle of medicine "Primum non nocere" (first, do no harm), that is to say to cure without harming. In addition, aprepitant has been shown to have no bone marrow toxicity [19], which is crucial since chemotherapy often leads to leukopenia and bone marrow aplasia. Moreover, combining NK-1R antagonists with cytostatic drugs enhances their antitumour activity, and pretreatment with NK-1R antagonists has been shown to partially protect fibroblasts from cytostatic drug toxicity [67].

It is important to note that aprepitant is authorized for the CINV, and at the recommended dose for TC therapy (20-40 mg/kg/day), it is not carcinogenic. Furthermore, aprepitant has a high therapeutic index compared to chemotherapy, which is known for its low safety margin [17]. Although there are limited experiences with higher doses of aprepitant in humans, some case reports have shown positive outcomes. For instance, a lung cancer patient treated with a combination of aprepitant (1140 mg/day for 45 days) and palliative radiotherapy exhibited complete tumour regression with no severe side effects [68]. Similarly, a clinical trial demonstrated that aprepitant at a dose of 300 mg/day for 45 days was as effective as paroxetine in treating moderate to severe depression, with similar side effects to placebo [38]. Furthermore, aprepitant (375 mg/day) administered to HIV patients for 2 weeks was safe, well-tolerated, and resulted in decreased levels of CD4+ PD1-positive cells and substance P plasma levels [70].

3.6. Chemotherapy versus NK-1R Antagonists (Aprepitant) in TC Patients

Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are currently the mainstays of cancer treatment. However, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are limited by cancer cell resistance and severe side effects. Therefore, there is a need to explore new and more effective drugs that can overcome resistance and reduce side effects when used in combination with conventional therapies. NK-1R antagonists, such as aprepitant, have broad-spectrum antitumour activity [20] and NK-1R has been shown to be essential for the survival of tumor cells, but it is not for normal non-tumor cells [15]. These agents belong to a new generation of anticancer drugs known as "intelligent bullets," which are both parasitotropic (targeting tumour cells) and non-organotropic (without severe side effects) and have other therapeutic effects in cancer patients [17,20]. The concept of "intelligent bullets" expands upon Paul Ehrlich's 1908 Nobel prize-winning concept of "magic bullets," which were based on the pharmacological properties of side chains (receptors). These "intelligent bullets" in cancer patients have antitumour activity such as inhibiting tumour cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, counteracting the Warburg effect, inhibiting angiogenesis, and preventing tumour cells migration (invasion and metastasis). Remarkably, they also exhibit other therapeutic effects, including antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, anti-nausea and vomiting, cough suppressant, and antipruritic effects [17,38,55,66]. Furthermore, when used in combination with radiotherapy or chemotherapy, NK-1R antagonists not only enhance the antitumour activity of chemotherapy but also reduce their severe side effects, providing neuroprotection, cardioprotection, hepatoprotection, and nephroprotection [71].

4. Conclusion

Thyroid cancer (TC) is characterized by the overexpression of SP and NK-1R compared to normal thyroid tissue. SP acts through autocrine, paracrine, intracrine, and endocrine mechanisms, promoting TC cell proliferation, activating the Warburg effect, inhibiting apoptosis, stimulating angiogenesis, and facilitating cell migration for invasion and metastasis. Elevated SP plasma levels in TC patients suggest a potential role in paraneoplastic syndromes. NK-1R is essential for cancer cells, but not for normal non-tumour cells. Therefore, NK-1R antagonists can selectively inhibit TC cell proliferation, counteract the Warburg effect, induce apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis, and suppress TC cell migration to prevent invasion and metastasis. Unlike chemotherapy, NK-1R antagonists such as aprepitant have demonstrated minimal side effects and additional therapeutic benefits, including antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, antiemetic, cough suppressant, and antipruritic effects. The findings support the use of aprepitant in TC patients and highlight the potential for developing new drugs targeting NK-1R in TC and TC metastasis treatment. Aprepitant should be considered as an antitumour drug, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy for TC therapy. Future phase I and II clinical trials are necessary to evaluate its safety and efficacy in TC patients.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This is a review article, and no new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Javier Muñoz (Seville University) for his technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Torre, L.A.; Bray, F.; Siegel, RL.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 87-108. [CrossRef]

- Sherman SI. Thyroid carcinoma. Lancet 2003, 361, 501-11.

- Kim, KW.; Park, Y.J., Kim, E.H. Elevated risk of papillary thyroid cancer in Korean patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Head Neck 2011, 33, 691-5.

- Pusztaszeri, M.P.; Sadow, P.M.; Faquin. W.C. CD117: a novel ancillary marker for papillary thyroid carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014, 122, 596-603. [CrossRef]

- Ragazzi, MA.; Ciarrocchi, V.; Sancisi, G.; Gandolfi, A.; Bisagni, A.; Piana S. Update on anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: morphological, molecular, and genetic features of the most aggressive thyroid cancer. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 790834.

- Haugen, B.; Sherman, S.I. Evolving approaches to patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocrine Reviews 2013, 34, 439-455. [CrossRef]

- Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B.; Schechter, R.B.; Shih, Y.C.; Kaplan, E.L; Chiu, B.C.; Angelos, P.; et al. The clinical and economic burden of a sustained increase in thyroid cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22, 1252-9. [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, M.; Ohashi, Y.; Schichijo, S.; Christian, C.; Sudduth-Klinger, J.; Harrowe, G.; et al. Multiple intracellular signalling pathways of the neuropeptide SP receptor. J. Neurosci. Res. 1992, 32, 437-43.

- Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Díez, J.J.; Durán, M.; Grande, E. Advances in thyroid cancer treatment: latest evidence and clinical potential. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2015, 72, 22-38. [CrossRef]

- Pennefather, J.N.; Lecci, A.; Candenas, M.L.; Patak, E.; Pinto, F.M.; Maggi, C.A. “Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: a growing family.” Life sciences 2004, 74, 1445-63. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Blount, P.; Sachais, B.S.; Hershey, A.D.; Raddatz, R.; Krause, J. Ligand binding kinetics of substance P and neurokinin A receptors stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells and evidence for differential stimulation of inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate and cyclic AMP second messenger responses. J. Neurochem. 1992, 59,740-5. [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.M.; Anderson, S.A.; Yu, H.; Huang, R.R.; Strader, C.D. Differential activation of intracellular effector by two isoforms of human neurokinin-1 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992, 41,24-30.

- Berger, M.; Neth, O.; Ilmer, M.; Garnier, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; de Agustín Asencio, J.C.; et al. Hepatoblastoma cells express truncated neurokinin-1 receptor and can be growth inhibited by aprepitant in vitro and in vivo. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60: 985-94. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao. L.; Xiong, T.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Yao, Z. Roles of full-length and truncated neurokinin-1 receptors on tumor progression and distant metastasis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 140,49-61. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S.; Rosso, M.; Medina, R.; Coveñas, R.; Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Is Essential for the Viability of Human Glioma Cells: A Possible Target for Treating Glioblastoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6291504. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz. M.; Coveñas.; Esteban, F.; Redondo, M. The substance P/NK-1 receptor system: NK-1 receptor antagonists as anti-cancer drugs. J. Biosci. 2015, 40, 441-63.

- Munoz, M.; Covenas, R. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Aprepitant: An Intelligent Bullet against Cancer? Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. 2682.

- Muñoz, M.; Pérez, A.; Rosso, M.; Zamarriego, C.; Rosso, R. Antitumoral action of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist L-733,060 on human melanoma cell lines. Melanoma Res. 2004, 14, 183-8. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Quintana, A.; Trujillo-Hacha, P.; Piruat, J.I.; Bejarano-Garcia, J.A.; Garcia-Guerrero. E.; Perez-Simon, J.A.; Munoz, M. Human acute myeloid leukemia cells express Neurokinin-1 receptor, which is involved in the antileukemic effect of Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Invest. New Drugs 2019, 37,17-26. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M. The NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant as a broad-spectrum antitumor drug. Invest. New. Drugs 2010, 28, 187-93. [CrossRef]

- Isorna, I.; Esteban, F.; Solanellas, J.; Coveñas, R.; Muñoz, M. The substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor system in human thyroid cancer: an immunohistochemical study. Eur. J. Histochem. 2020, 64,3117. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Coveñas, R. A new frontier in the treatment of cancer: NK-1 receptor antagonists. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 504-16. [CrossRef]

- Skrabanek, P.; Cannon, D.; Dempsey, J.; Kirrane, J.; Neligan, M.; Powell D. Substance P in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Experientia 1979, 35, 1259-60. [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Nesland, J.M.; Gould, V.E.; Johannessen, J.V. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland: an immunocytochemical study. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1985, 8, 25-41. [CrossRef]

- Hennig, I.M.; Laissue, J.A.; Horisberger, U.; Reubi, J.C. Substance-P receptors in human primary neoplasms: tumoral and vascular localization. Int. J. Cancer 1995, 61, 786-92. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Mirdoosti, S.M.; Majidi, S.; Boroumand, N.; Jafarian, A.H. Hashemy, S.I. Evaluation of serum substance P level and tissue distribution of NK-1 receptor in papillary thyroid cancer. Middle East J. Cancer. 2021, 12,491-8. [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.A..; Mosqueda-Taylor, A.; Esteban, F.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Díaz-Franco, M.A.; Delgado, M et al. Cell proliferation associated with actions of the substance P/NK-1 receptor complex in keratocystic odontogenic tumours. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 1127-33. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Carranza, A.; Coveñas, R. Increased nuclear localization of substance P in human gastric tumor cells. Acta. Histochem. 2017, 119, 337-42. [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Yang, J.; Tong, L.; Yuan, Y.; Tian, Y.; Hong, L et al. Substance P immunoreactive nerve fibres are related to gastric cancer differentiation status and could promote proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. Cell. Biol. Int. 2011, 35, 623-9. [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.; Robles-Frías, M.J.; Coveñas, R.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Muñoz, M. The NK-1 receptor is expressed in human primary gastric and colon adenocarcinomas and is involved in the antitumor action of L-733,060 and the mitogenic action of substance P on human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. Tumor Biol. 2008, 29, 245-54. [CrossRef]

- Esteban, F.; González-Moles, M.A.; Castro, D.; Martín-Jaén, M. del M.; Redondo, M.; Ruiz-Avila, I.; et al. Expression of substance P and neurokinin-1-receptor in laryngeal cancer: linking chronic inflammation to cancer promotion and progression. Histopathology 2009, 54, 258-60. [CrossRef]

- Brener, S.; González-Moles, M.A.; Tostes, D.; Esteban, F.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Ruiz-Avila, I.; et al. A role for the substance P/NK-1 receptor complex in cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 2323-9.

- Muñoz, M.; González-Ortega, A,; Rosso M, Robles-Frías MJ, Carranza, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; et al. The substance P/neurokinin-1 receptor system in lung cancer: focus on the antitumor action of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Peptides 2012, 38, 318-25. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Robles-Frías, M.J.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Rosso, R.; González-Ortega, A.; et al. The NK-1 receptor is expressed in human melanoma and is involved in the antitumor action of the NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on melanoma cell lines. Lab. Invest. 2010, 90, 1259-69. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; González-Ortega, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Carranza, A.; García-Recio, S.; Almendro, V.; et al. The neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant is a promising candidate for the treatment of breast cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1658-72. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Pavón, A.; Rosso, M.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Pérez, A.; Carranza, A.; et al. Immunolocalization of NK-1 receptor and substance P in human normal placenta. Placenta 2010, 31, 649-51. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Muñoz, M.F.; Ayala, A. Immunolocalization of Substance P and NK-1 Receptor in ADIPOSE Stem Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017,118,4686-4696.

- Kramer, M.S.; Cutler, N.; Feighner, J.; Shrivastava, R.; Carman, J.; Sramek, J.J.; Reines, S.A.; Liu, G.; Snavely, D.; Wyatt-Knowles, E.; et al: Distinct mechanism for antidepressant activity by blockade of central substance P receptors. Science 1998, 281,1640-1645.

- Ortiz-Prieto, A.; Bernabeu-Witte, J.; Zulueta-Dorado, T.; Lorente-Lavirgen, A.I.; Muñoz, M. Immunolocalization of substance P and NK-1 receptor in vascular anomalies. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2017, 309, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.H.; Tamizhselvi, R.; Bhatia, M. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, through nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1, contribute to caerulein-induced expression of substance P and neurokinin-1 receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010; 332. 940-8. [CrossRef]

- Walczak-Drzewiecka, A.; Ratajewski, M.; Wagner, W.; Dastych, J. HIF-1alpha is up-regulated in activated mast cells by a process that involves calcineurin and NFAT. J. Inmunol. 2008, 181, 1665-72. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Sharif, T.R.; Sharif, M. Substance P-induced mitogenesis in human astrocytoma cells correlates with activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 1996, 56. 4983-91.

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in cancer. Peptides 2013, 48, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Recio, S.; Fuster, G.; Fernandez-Nogueira, P. Substance P autocrine signaling contributes to persistent HER2 activation that drives malignant progression and drug resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013,73, 6424-6434. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Pérez, A.; Coveñas, R.; Rosso, M.; Zamarriego, C.; et al. The NK1 receptor is involved in the antitumoural action of L-733,060 and in the mitogenic action of substance P on neuroblastoma and glioma cell lines. Neuropeptides 2005,39, 427-32. [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Eibl, G.; Kisfalvi, K.; Fan, R.S.; Burdick, M.; Reber, H.; et al. Broad-spectrum G protein-coupled receptor antagonist, [D-Arg1, DTrp5,7,9, Leu11] SP: a dual inhibitor of growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 2738-45.

- 47. Castagliuolo I, Valenick L, Liu J, Pothoulakis C. Epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates substance P-induced mitogenic responses in U-373 MG cells. J Biol Chem. 2000 Aug 25;275(34):26545-50. [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, T.; Kwatra, S.G.; Goldsmith, L.E.; Richardson, M.D.; Cox, E.A.; Sampson, J.H.; et al. A constitutively active form of neurokinin 1 receptor and neurokinin 1 receptor-mediated apoptosis in glioblastomas. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109, 1079-86. [CrossRef]

- Ziche, M.; Morbidelli, L.; Pacini, M.; Geppetti, P.; Alessandri, G.; Maggi, C.A. Substance P stimulates neovascularization in vivo and proliferation of cultured endothelial cells. Microvasc. Res. 1990, 40,264-278. [CrossRef]

- Rubinow, K.B. An intracrine view of sex steroids, immunity, and metabolic regulation. Mol. Metab. 2018, 15,92-103. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, D. Contribution of phenylalanine side chain intercalation to the TATA-box binding protein-DNA interaction: molecular dynamics and dispersion-corrected density functional theory studies. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20,2499. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.M.; Leeman, S.E.; Niall, H.D. Amino-acid sequence of substance P. Nat. New. Biol. 1971,232,86-7. [CrossRef]

- Skrabanek, P.; Cannon, D.; Dempsey, J.; Kirrane, J.; Neligan, M.; Powell, D.. “Substance P in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid.” Experientia 1979, 35, 1259-60. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Tucker, K.L.; Sage, T.; Kaiser, W.J.; Barrett, N.E.; Lowry, P.J.; et al. Peripheral tachykinins and the neurokinin receptor NK1 are required for platelet thrombus formation. Blood 2008, 111, 605-12. [CrossRef]

- Ständer, S.; Siepmann, D.; Herrgott, I.; Sunderkötter, C.; Luger, T.A. Targeting the neurokinin receptor 1 with aprepitant: a novel antipruritic strategy. PLoS One 2010,5, e10968.

- Coveñas, R.; Muñoz, M. “Involvement of the Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Receptor System in Cancer” Cancers 2022, 14,3539.

- Alsaeed, M.A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Alalikhan, A.; Hashemi. S.F.; Hashemy, S.I. The Potential In Vitro Inhibitory Effects of Neurokinin-1 Receptor (NK-1R) Antagonist, Aprepitant, in Osteosarcoma Cell Migration and Metastasis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022,8082608. [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123,309-314. [CrossRef]

- Medrano, S.; Gruenstein, E.; Dimlich, R.V. Substance P receptors on human astrocytoma cells are linked to glycogen breakdown. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 167, 14-8. [CrossRef]

- Vasko, VV.; Saji, M. Molecular mechanisms involved in differentiated thyroid cancer invasion and metastasis. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2007, 19,11-7.

- Sporn, M.B. The war on cancer. Lancet 1996, 347,1377-81.

- Meshki, J.; Douglas, S.D.; Hu, M.; Leeman, S.E.; Tuluc, F. Substance P induces rapid and transient membrane blebbing in U373MG cells in a p21-activated kinase-dependent manner. PLoS One 2011, 6, e25332. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yuan, S.; Cheng, J.; Kang, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J. Substance P promotes the progression of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 845-50. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Javid, H.; Afshari, A.R.; Mashkani, B.; Hashemy, S.I. Substance P accelerates the progression of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF-A, and VEGFR1 overexpression. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47,4263-4272. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Safety of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Expert. Opin. Drug. Saf. 2013, 12, 673–685. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.K.; Kohli, A. Aprepitant. [Updated 2022 Sep 22]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Turner, R.D.; Birring, S.S. Neurokinin-1 Receptor Inhibition and Cough. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021,203,672-674. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Berger. M.; Rosso, M.; Gonzalez-Ortega, A.; Carranza, A.; Coveñas, R. Antitumor activity of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in MG-63 human osteosarcoma xenografts. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44,137-46. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Crespo, J.C.; Crespo, J.P.; Coveñas, R. Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant and radiotherapy, a successful combination therapy in a patient with lung cancer: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 11,50-54.

- Tebas, P; Spitsin, S.; Barrett, J.S.; Tuluc, F.; Elci, O.; Korelitz, J.J.; Wagner, W.; Winters, A.; Kim, D.; Catalano, R.; Evans, D.L.; Douglas, S.D. Reduction of soluble CD163, substance P, programmed death 1 and inflammatory markers: phase 1B trial of aprepitant in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS 2015, 29, 931-9.

- Robinson, P.; Coveñas, R.; Muñoz, M. Combination Therapy of Chemotherapy or Radiotherapy and the Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Aprepitant: A New Antitumor Strategy? Curr. Med. Chem. 2023,30,1798-1812.

Figure 1.

SP functions in TC.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Downloads

100

Views

68

Comments

0

Subscription

Notify me about updates to this article or when a peer-reviewed version is published.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2025 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated