Submitted:

14 September 2023

Posted:

18 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

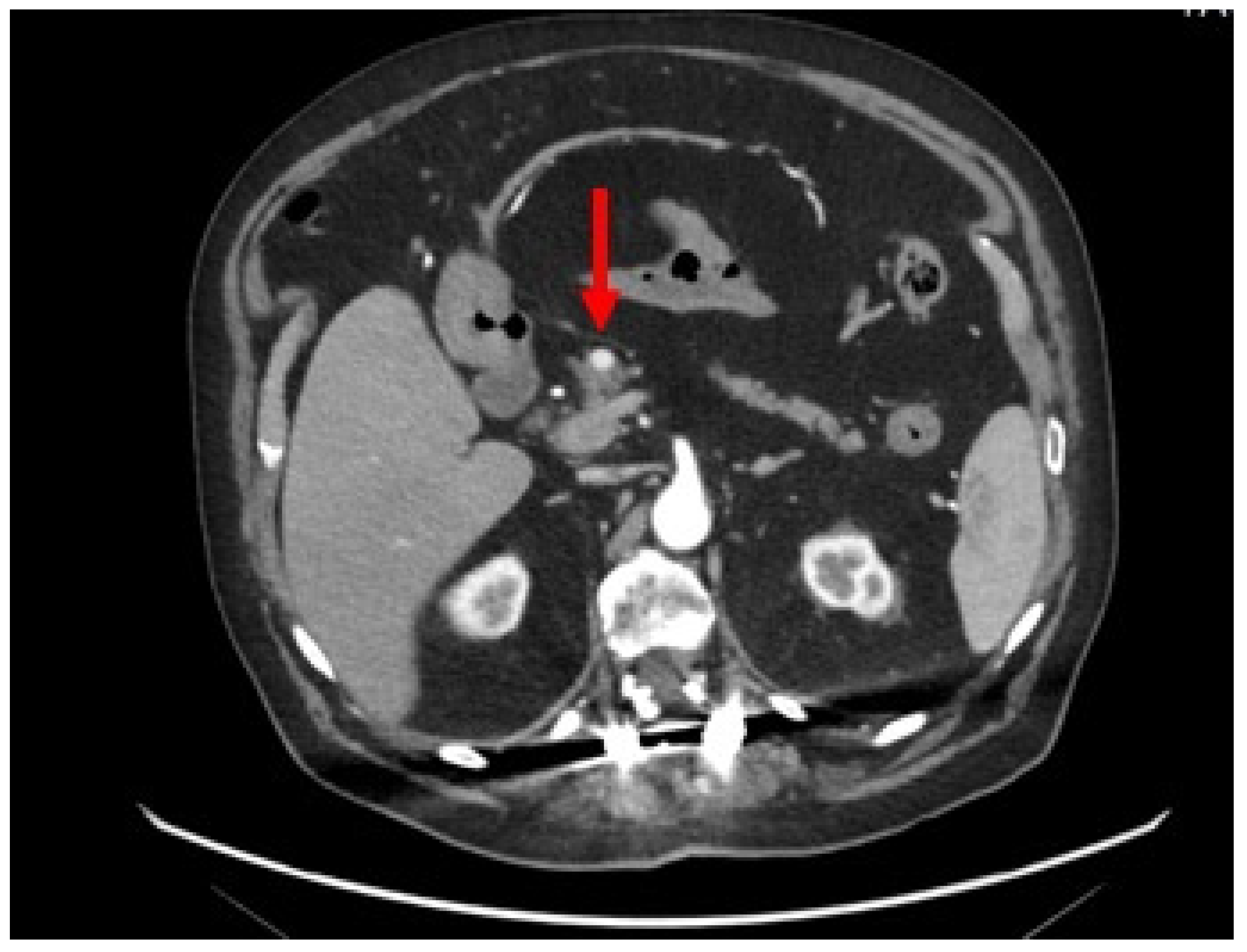

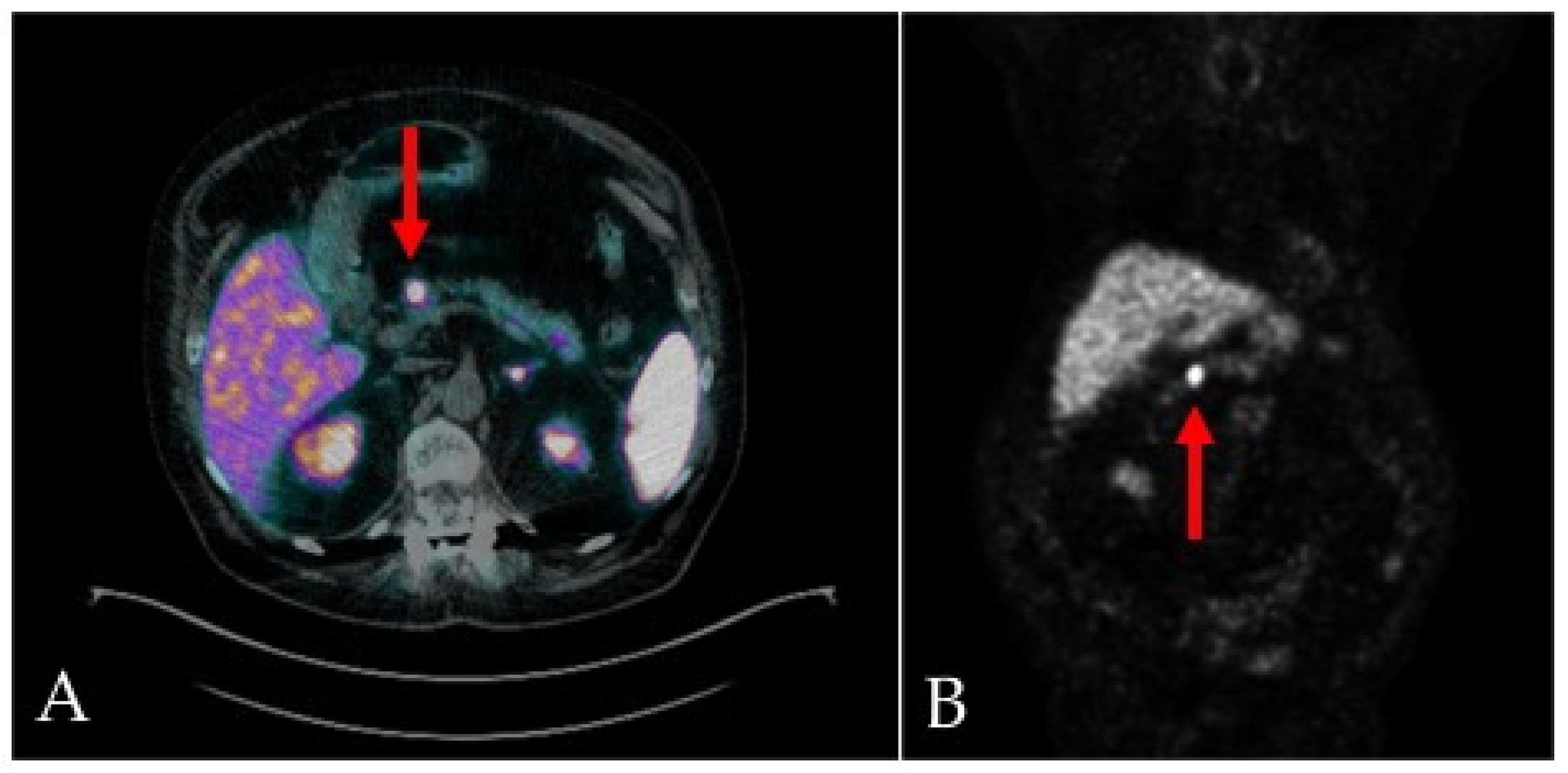

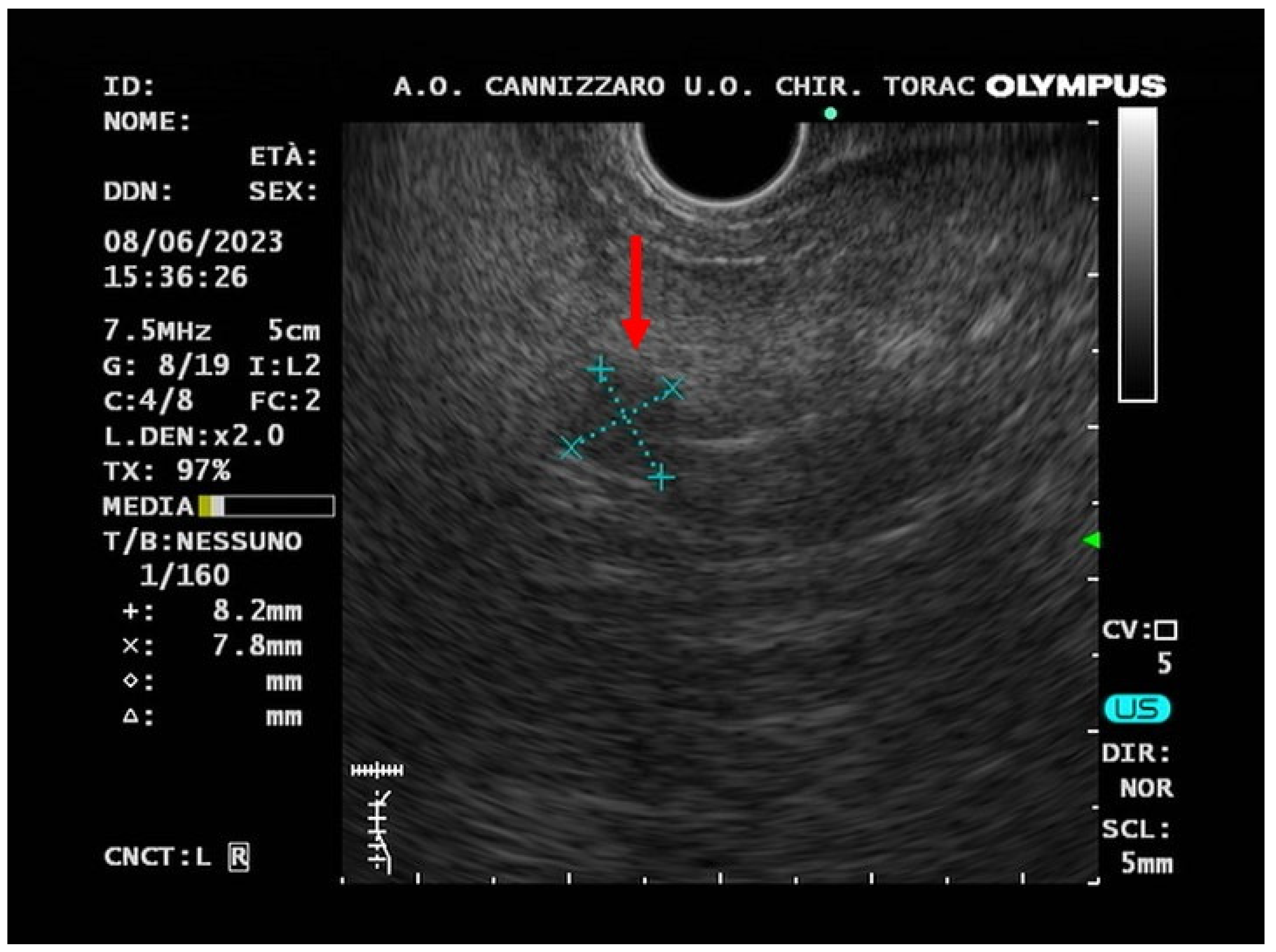

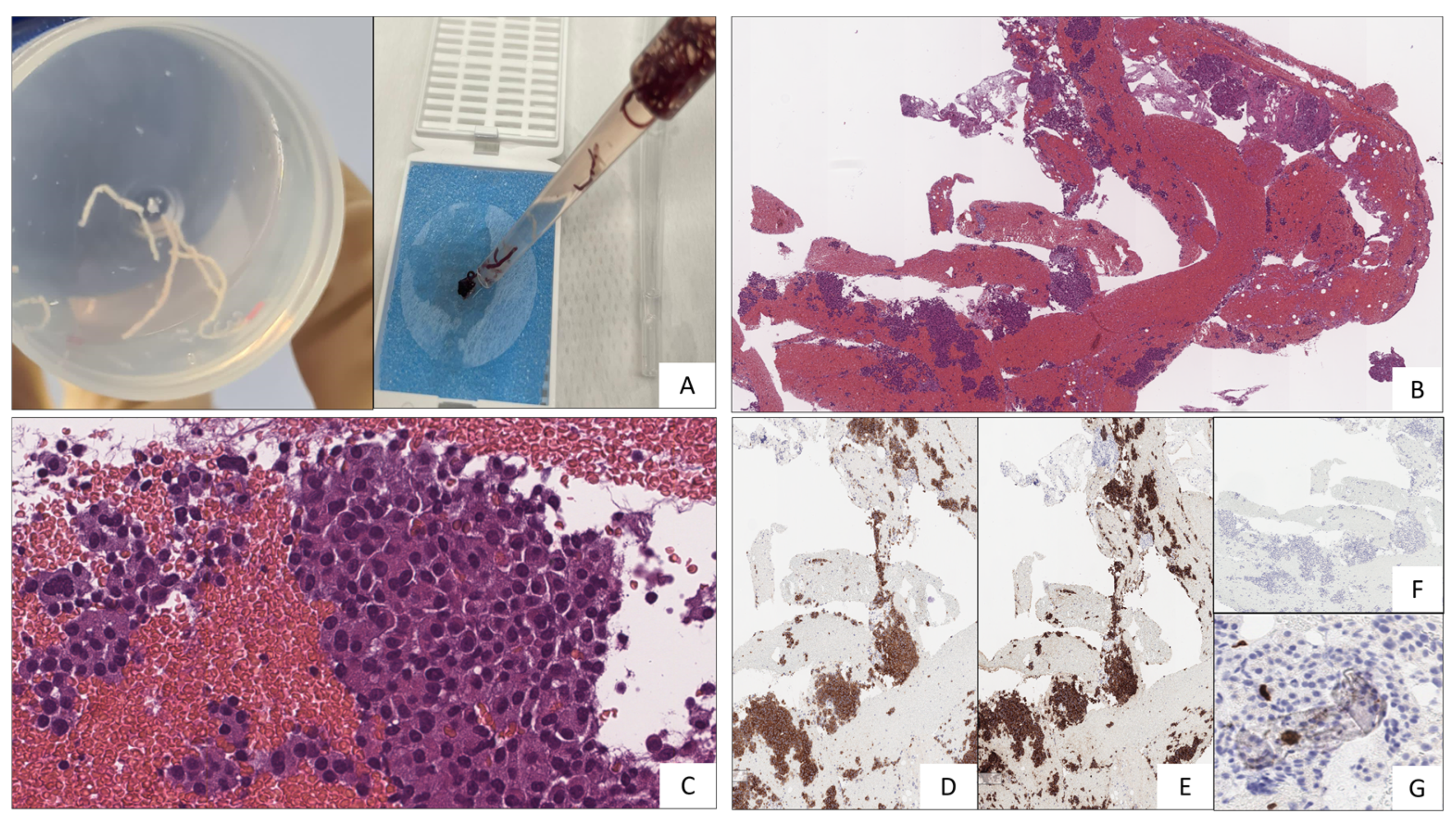

2. Case-report

3. Review of the Literature

4. Discussion

List of Acronyms

| APUD: Amine Precursor Uptake and Decarboxylation CgA: Chromogranin A CHD: Carcinoid heart disease Cr: Creatinine CT: Computed tomography CRP: C-reactive protein eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate ENETS: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration EUS-FNB: Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle biopsy FAST: Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma 68Ga-DOTA-NOC: gallium-68-DOTA-Nal3-octreotide 68Ga-DOTA-TATE: gallium-68-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotate 68Ga-DOTA-TOC: gallium-68-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotide GEP-NEN: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm GEP-NET: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor HGT: Hemo Glucose Test 5-HIAA: 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid 5-HT: serotonin INSM1: insulinoma-associated protein 1 JNETS: Japanese Neuroendocrine Tumor Society MEN-1: Multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 MiNEN: Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging NF-P-NET: Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor NEC: Neuroendocrine carcinoma NEN: Neuroendocrine neoplasm NET: Neuroendocrine tumor NSE: Neuron-specific enolase P-NET: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor PAD: Peripheral artery disease PET: Positive emission tomography PPi: Proton pomp inhibitor SaO2: Oxygen saturation SSA: Somatostatin analogue SSTR: Somatostatin receptor VHL: von Hippel-Lindau syndrome VIP: Vaso-active intestinal peptide WHO: World health organization |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, J. C.; Hassan, M.; Phan, A.; Dagohoy, C.; Leary, C.; Mares, J. E.; Abdalla, E. K.; Fleming, J. B.; Vauthey, J. N.; Rashid, A.; Evans, D. B. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 3063–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Dasari, A. Epidemiology, Incidence, and Prevalence of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Are There Global Differences? Current oncology reports 2021, 23(4), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, E.; Boffetta, P.; Shafir, M.; Aleksovska, K.; Boccia, S.; Rindi, G. Increased incidence trend of low-grade and high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine 2017, 58(2), 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Öberg, K.; Falconi, M.; Krenning, E. P.; Sundin, A.; Perren, A.; Berruti, A.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2020, 31(7), 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Shen, C.; Halperin, D.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Shih, T.; Yao, J. C. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA oncology 2017, 3(10), 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, D.; Ramage, J.; Srirajaskanthan, R. Update on Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Complications of Carcinoid Syndrome. Journal of oncology 2020, 8341426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, D. C.; Jensen, R. T. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology 2008, 135(5), 1469–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Capdevila, J.; Crespo-Herrero, G.; Díaz-Pérez, J. A.; Martínez Del Prado, M. P.; Alonso Orduña, V.; Sevilla-García, I.; Villabona-Artero, C.; Beguiristain-Gómez, A.; Llanos-Muñoz, M. et al. Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE). Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2010, 21(9), 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIOM for Neuroendocrine Tumors Guide Line 2020. Accessed 15 July 2023 https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020_LG_AIOM_Neuroendocrini.pdf.

- Ordóñez, N. G. Broad-spectrum immunohistochemical epithelial markers: a review. Human pathology 2013, 44(7), 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moertel, C. G. Karnofsky memorial lecture. An odyssey in the land of small tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1987, 5(10), 1502–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Igarashi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Sasano, H.; Okusaka, T.; Takano, K.; Komoto, I.; Tanaka, M.; Imamura, M.; Jensen, R. T.; Takayanagi, R.; Shimatsu, A. Epidemiological trends of pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in Japan: a nationwide survey analysis. Journal of gastroenterology 2015, 50(1), 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M. Y.; Kim, J. M.; Sohn, J. H.; Kim, M. J.; Kim, K. M.; Kim, W. H.; Kim, H.; Kook, M. C.; Park, D. Y.; Lee, J. H.; et al. Current Trends of the Incidence and Pathological Diagnosis of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (GEP-NETs) in Korea 2000-2009: Multicenter Study. Cancer research and treatment 2012, 44(3), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherübl, H.; Streller, B.; Stabenow, R.; Herbst, H.; Höpfner, M.; Schwertner, C.; Steinberg, J.; Eick, J.; Ring, W.; Tiwari, K.; et al. Clinically detected gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are on the rise: epidemiological changes in Germany. World journal of gastroenterology 2013, 19(47), 9012–9019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, B. E.; Rous, B.; Chandrakumaran, K.; Wong, K.; Bouvier, C.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; George, G.; Russell, B.; Srirajaskanthan, R.; Ramage, J. K. Incidence and survival of neuroendocrine neoplasia in England 1995-2018: A retrospective, population-based study. The Lancet regional health. Europe 2022, 23, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, I. D.; Odze, R. D.; Klimstra, D.; Paradis, V.; Rugge, M.; Schirmacher, P.; Washington, K. M.; Carneiro, F.; Cree, I. A.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 2020, 76(2), 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C. J.; Agarwal, M.; Pottakkat, B.; Haroon, N. N.; George, A. S; Pappachan, J. M. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A clinical snapshot. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery 2021, 13(3), 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraghmeh, L., Shbaita, S., Nassef, O., Melhem, L., & Maqboul, I. (2023). Non-specific Symptoms of Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumor and the Diagnostic Challenges: A Case Report. Cureus 15(6), e41080. [CrossRef]

- Klöppel, G.; Perren, A.; Heitz, P. U. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2004, 1014, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.V.; Osamura, R.Y.; Klöppel, G.; Rosai, J. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs, 2017 vol. 10. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Modlin, I. M.; Lye, K. D.; Kidd, M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003, 97(4), 934–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cives, M.; Strosberg, J. R. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2018, 68(6), 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turaga, K.K.; Kvols, L.K. Recent progress in the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011, 61(2), 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbi, A.; Falconi, M.; Rindi, G.; Delle Fave, G.; Tomassetti, P.; Pasquali, C.; Capitanio, V.; Boninsegna, L.; Di Carlo, V.; AISP-Network Study Group. Clinicopathological features of pancreatic endocrine tumors: a prospective multicenter study in Italy of 297 sporadic cases. The American journal of gastroenterology 2010, 105(6), 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. T.; Cadiot, G.; Brandi, M. L.; de Herder, W. W.; Kaltsas, G.; Komminoth, P.; Scoazec, J. Y.; Salazar, R.; Sauvanet, A.; Kianmanesh, R.; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology 2012, 95(2), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, A. K.; Olariu, E.; Douthit, N. T. Carcinoid Syndrome: A Review. Cureus 2020, 12(3), e7186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, D. M.; Shen, C.; Dasari, A.; Xu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Shih, Y. T.; Yao, J. C. Frequency of carcinoid syndrome at neuroendocrine tumour diagnosis: a population-based study. The Lancet. Oncology 2017, 18(4), 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, J. M.; Sousa, L. G.; Riechelmann, R. P. Complications from carcinoid syndrome: review of the current evidence. Ecancermedicalscience 2016, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvols L., K. Metastatic carcinoid tumors and the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1994, 733, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in 2020. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology 2020, 12(8), 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Davar, J.; Dreyfus, G.; Caplin, M. E. Carcinoid heart disease. Circulation 2007, 116(24), 2860–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druce, M.; Rockall, A.; Grossman, A. B. Fibrosis and carcinoid syndrome: from causation to future therapy. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2009, 5(5), 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, R.; Burgess, M. I.; Pritchard, D. M.; Cuthbertson, D. J. The clinical presentation and management of carcinoid heart disease. International journal of cardiology 2014, 173(1), 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin de Celis Ferrari, A. C.; Glasberg, J.; Riechelmann, R. P. Carcinoid syndrome: update on the pathophysiology and treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2018, 73 (suppl 1), e490s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, S.; Boon, J. C.; Kema, I. P.; Willemse, P. H.; den Boer, J. A.; Korf, J.; de Vries, E. G. Patients with carcinoid syndrome exhibit symptoms of aggressive impulse dysregulation. Psychosomatic medicine 2004, 66(3), 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohen, I.; Arbouet, S. Neuroendocrine carcinoid cancer associated with psychosis. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)) 2008, 5(6), 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nobels, A.; Geboes, K.; Lemmens, G. M. May depressed and anxious patients with carcinoid syndrome benefit from treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)?: findings from a case report. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2016, 55(11), 1370–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsumoto, S.; Kodama, Y.; Sakurai, Y.; Shinohara, T.; Katanuma, A.; Maguchi, H. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm: correlation between computed tomography enhancement patterns and prognostic factors of surgical and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Abdominal imaging 2013, 38(2), 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, F.; Albertelli, M.; Brisigotti, M. P.; Borra, T.; Boschetti, M.; Fiocca, R.; Ferone, D.; Mastracci, L. Grade Increases in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Metastases Compared to the Primary Tumor. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103(5), 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq, M.; Bhutani, M. S.; Bektas, M.; Lee, J. E.; Gong, Y.; Tamm, E. P.; Shah, C. P.; Ross, W. A.; Yao, J.; Raju, G. S. et al. EUS-FNA for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a tertiary cancer center experience. Digestive diseases and sciences 2012, 57(3), 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larghi, A.; Capurso, G.; Carnuccio, A.; Ricci, R.; Alfieri, S.; Galasso, D.; Lugli, F.; Bianchi, A.; Panzuto, F.; De Marinis, L. et al. Ki-67 grading of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors on histologic samples obtained by EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition: a prospective study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2012, 76(3), 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unno, J.; Kanno, A.; Masamune, A.; Kasajima, A.; Fujishima, F.; Ishida, K.; Hamada, S.; Kume, K.; Kikuta, K.; Hirota, M. et al. The usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors based on the World Health Organization classification. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 2014, 49(11), 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiella, S.; Landoni, L.; Rota, R.; Valenti, M.; Elio, G.; Crinò, S. F.; Manfrin, E.; Parisi, A.; Cingarlini, S; D'Onofrio, M. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis and grading of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a retrospective analysis of 110 cases. Endoscopy 2020, 52(11), 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crinò, S. F.; Ammendola, S.; Meneghetti, A.; Bernardoni, L.; Conti Bellocchi, M. C.; Gabbrielli, A.; Landoni, L.; Paiella, S.; Pin, F.; Parisi, A. et al. Comparison between EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology and EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy histology for the evaluation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreatology 2021, 21(2), 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimbaş, M.; Crino, S. F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Costamagna, G.; Scarpa, A.; Larghi, A. EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition for solid pancreatic lesions: Finally moving from fine-needle aspiration to fine-needle biopsy? Endoscopic ultrasound 2018, 7(3), 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eusebi, L. H.; Thorburn, D.; Toumpanakis, C.; Frazzoni, L.; Johnson, G.; Vessal, S.; Luong, T. V.; Caplin, M.; Pereira, S. P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration vs fine-needle biopsy for the diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopy international open 2019, 7(11), E1393–E1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, M.; Poliani, L.; Rahal, D.; Auriemma, F.; Anderloni, A.; Ridolfi, C.; Spaggiari, P.; Capretti, G.; Di Tommaso, L.; Preatoni, P. et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours: The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound Biopsy in Diagnosis and Grading Based on the WHO 2017 Classification. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 37(4), 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeds, J. S.; Nayar, M. K.; Bekkali, N. L. H.; Wilson, C. H.; Johnson, S. J.; Haugk, B.; Darne, A.; Oppong, K. W. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy is superior to fine-needle aspiration in assessing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopy international open 2019, 7(10), E1281–E1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melita, G.; Pallio, S.; Tortora, A.; Crinò, S. F.; Macrì, A.; Dionigi, G. Diagnostic and Interventional Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Journal of clinical medicine 2021, 10(12), 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Ustun, B.; Alomari, A.; Bao, F.; Aslanian, H. R.; Siddiqui, U.; Chhieng, D.; Cai, G. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in diagnosing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CytoJournal 2013, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsen, L.; Jouret-Mourin, A.; Borbath, I.; van Maanen, A.; Weynand, B. Accuracy of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumour Grading by Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration: Analysis of a Large Cohort and Perspectives for Improvement. Neuroendocrinology 2018, 106(2), 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidsma, C. M.; Tsilimigras, D. I.; Rocha, F.; Abbott, D. E.; Fields, R.; Smith, P. M.; Poultsides, G. A.; Cho, C.; van Eijck, C.; van Dijkum, E. N. et al. Clinical relevance of performing endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors less than 2 cm. Journal of surgical oncology 2020, 122(7), 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratian, L.; Pura, J.; Dinan, M.; Roman, S.; Reed, S.; Sosa, J. A. Impact of extent of surgery on survival in patients with small nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. Annals of surgical oncology 2014, 21(11), 3515–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, S. M.; In, H.; Winchester, D. J.; Talamonti, M. S.; Baker, M. S. Surgical resection provides an overall survival benefit for patients with small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery 2015, 19(1), 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallinen, V.; Haglund, C.; Seppänen, H. Outcomes of resected nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Do size and symptoms matter? Surgery 2015, 158(6), 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconi, M.; Eriksson, B.; Kaltsas, G.; Bartsch, D. K.; Capdevila, J.; Caplin, M.; Kos-Kudla, B.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Rindi, G.; Klöppel, G. et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103(2), 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Fave, G.; O'Toole, D.; Sundin, A.; Taal, B.; Ferolla, P.; Ramage, J. K.; Ferone, D.; Ito, T.; Weber, W.; Zheng-Pei, Z. et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103(2), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramage, J. K.; De Herder, W. W.; Delle Fave, G.; Ferolla, P.; Ferone, D.; Ito, T.; Ruszniewski, P.; Sundin, A.; Weber, W.; Zheng-Pei, Z. et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103(2), 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, T.; Rodriguez Franco, S.; Kirsch, M. J.; Colborn, K. L.; Ishida, J.; Grandi, S.; Al-Musawi, M. H.; Gleisner, A.; Del Chiaro, M. et al. Evaluation of Survival Following Surgical Resection for Small Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. JAMA network open 2023, 6(3), e234096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Masui, T.; Komoto, I.; Doi, R.; Osamura, R. Y.; Sakurai, A.; Ikeda, M.; Takano, K.; Igarashi, H.; Shimatsu, A.; Nakamura, K. et al. JNETS clinical practice guidelines for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up: a synopsis. Journal of gastroenterology 2021, 56(11), 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadot, E.; Reidy-Lagunes, D. L.; Tang, L. H.; Do, R. K.; Gonen, M.; D'Angelica, M. I.; DeMatteo, R. P.; Kingham, T. P.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Untch, B. R. et al. Observation versus Resection for Small Asymptomatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Matched Case-Control Study. Annals of surgical oncology 2016, 23(4), 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, W. H.; Lee, H. S.; Lee, K. J.; Jang, S. I.; Lee, W. J.; Hwang, J. H.; Cho, C. M.; Park, C. H.; Han, J.; Woo, S. M. et al. Malignant potential of small pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm and its risk factors: A multicenter nationwide study. Pancreatology 2021, 21(1), 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, B.; Al-Toubah, T.; Montilla-Soler, J. Anatomic and functional imaging of neuroendocrine tumors. Current treatment options in oncology 2020, 21(9), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D. W.; Kim, M. K.; Kim, H. G. Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clinical endoscopy 2017, 50(6), 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, E.; Hubele, F.; Marzano, E.; Goichot, B.; Pessaux, P.; Kurtz, J. E.; Imperiale, A. Nuclear medicine imaging of gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The key role of cellular differentiation and tumor grade: from theory to clinical practice. Cancer imaging 2012, 12(1), 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, I.; Henze, M.; Engelbrecht, S.; Eisenhut, M.; Runz, A.; Schäfer, M.; Schilling, T.; Haufe, S.; Herrmann, T.; Haberkorn, U. Comparison of 68Ga-DOTATOC PET and 111In-DTPAOC (Octreoscan) SPECT in patients with neuroendocrine tumours. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2007, 34(10), 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Binnebeek, S.; Vanbilloen, B.; Baete, K.; Terwinghe, C.; Koole, M.; Mottaghy, F. M.; Clement, P. M.; Mortelmans, L.; Bogaerts, K.; Haustermans, K. et al. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of (111)In-pentetreotide SPECT and (68)Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT: A lesion-by-lesion analysis in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumours. European radiology 2016, 26(3), 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglia, G.; Castaldi, P.; Rindi, G.; Giordano, A.; Rufini, V. Diagnostic performance of Gallium-68 somatostatin receptor PET and PET/CT in patients with thoracic and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a meta-analysis. Endocrine 2012, 42(1), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M. F.; Virgolini, I.; Balogova, S.; Beheshti, M.; Rubello, D.; Decristoforo, C.; Ambrosini, V.; Kjaer, A.; Delgado-Bolton, R.; Kunikowska, J. et al. Guideline for PET/CT imaging of neuroendocrine neoplasms with 68Ga-DOTA-conjugated somatostatin receptor targeting peptides and 18F-DOPA. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2017, 44(9), 1588–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderup, T.; Knigge, U.; Loft, A.; Federspiel, B.; Kjaer, A. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts survival of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical cancer research 2010, 16(3), 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muffatti, F., Partelli, S., Cirocchi, R. et al. Combined 68Ga-DOTA-peptides and 18F-FDG PET in the diagnostic work-up of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN). Clin Transl Imaging 2019, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, P., Tam, H. H., Sharma, R., Aboagye, E. O., & Al-Nahhas, A. Frequency and significance of physiological versus pathological uptake of 68Ga-DOTATATE in the pancreas: validation with morphological imaging. Nuclear medicine communications 2014, 35(6), 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.; Torta, M.; Dittadi, R.; degli Uberti, E.; Ambrosio, M. R.; Delle Fave, G.; De Braud, F.; Tomassetti, P.; Gion, M.; Dogliotti, L. Comparison between two methods in the determination of circulating chromogranin A in neuroendocrine tumors (NETs): results of a prospective multicenter observational study. The International journal of biological markers 2005, 20(3), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welin, S.; Stridsberg, M.; Cunningham, J.; Granberg, D.; Skogseid, B.; Oberg, K.; Eriksson, B.; Janson, E. T. Elevated plasma chromogranin A is the first indication of recurrence in radically operated midgut carcinoid tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2009, 89(3), 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, A.; Lauretta, R.; Vottari, S.; Chiefari, A.; Barnabei, A.; Romanelli, F.; Appetecchia, M. Specific and Non-Specific Biomarkers in Neuroendocrine Gastroenteropancreatic Tumors. Cancers 2019, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, K.; Couvelard, A.; Delle Fave, G.; Gross, D.; Grossman, A.; Jensen, R. T.; Pape, U. F.; Perren, A.; Rindi, G.; Ruszniewski, P. et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Standard of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumours: Biochemical Markers. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 105(3), 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Y.; Gong, Y. F.; Zhuang, H. K.; Zhou, Z. X.; Huang, S. Z.; Zou, Y. P.; Huang, B. W.; Sun, Z. H.; Zhang, C. Z. et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A review of serum biomarkers, staging, and management. World journal of gastroenterology 2020, 26(19), 2305–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, J. M.; Jones, R. S. Carcinoid syndrome from gastrointestinal carcinoids without liver metastasis. Annals of surgery 1982, 196(1), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavras, N.; Schizas, D.; Machairas, N.; Damaskou, V.; Economopoulos, N.; Machairas, A. Carcinoid syndrome from a carcinoid tumor of the pancreas without liver metastases: A case report and literature review. Oncology letters 2017, 13(4), 2373–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famerée, L.; Van Lier, C.; Borbath, I.; Yildiz, H.; Lemaire, J.; Baeck, M. Misleading clinical presentation of carcinoid syndrome. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica 2021, 84(3), 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandee, W. T.; van Adrichem, R. C.; Kamp, K.; Feelders, R. A.; van Velthuysen, M. F.; de Herder, W. W. Incidence and prognostic value of serotonin secretion in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Clinical endocrinology 2017, 87(2), 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoilly, T.; Leroux, R.; Andrade, D.; Nicolle, R.; Dioguardi Burgio, M.; Marinoni, I.; Dokmak, S.; Ruszniewski, P.; Hentic, O.; Paradis, V. et al. Immunophenotypic and molecular characterization of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors producing serotonin. Modern pathology 2022, 35(11), 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, A. U.; Yook, C. R.; Hiremath, V.; Kasimis, B. S. Carcinoid syndrome in the absence of liver metastasis: a case report and review of literature. Medical and pediatric oncology 1992, 20(3), 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, K.; Janson, E. T.; Eriksson, B. Tumour markers in neuroendocrine tumours. Italian journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 1999, 31 Suppl 2, S160–S162. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, B., Oberg, K., & Stridsberg, M. Tumor markers in neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion 2000, 62 Suppl 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofland, J., Falconi, M., Christ, E., Castaño, J. P., Faggiano, A., Lamarca, A., Perren, A., Petrucci, S., Prasad, V., Ruszniewski, P., Thirlwell, C., Vullierme, M. P., Welin, S., & Bartsch, D. K. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society 2023 guidance paper for functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour syndromes. Journal of neuroendocrinology 2023, 35(8), e13318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Differentiation | Grade | Mitotic rate (mitoses/2 mm2) | Ki-67 index | |

| NET, G1 | Well differentiated | Low | <2 | <3% |

| NET, G2 | Intermediate | 2-20 | 3-20% | |

| NET, G3 | High | >20 | >20% | |

| NEC, small-cell type | Poorly differentiated | High | >20 | >20% |

| NEC, large-cell type | >20 | >20% | ||

| MiNEN | Well or poorly differentiated | Variable | Variable | Variable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).