1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) proclaimed the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic in March 2020 [

1]. A rapid emergence and subsequent dominance of new variants on global scale have become characteristic features of SARS-CoV-2 [

2]. The Omicron variant and the time period of its global dominance over other lineages, which can be defined as the Omicron era, relative to previous variants, was characterized by a less severe disease course, lower risk of hospitalization, ICU-admission and death [

3,

4]. In the general population, this is due to a high rate of immunization by means of vaccination and repeated infection, less severe infections due to changes in the virus genome for Omicron variant, the latter of which are in part counterbalanced by a reduction in vaccine effectiveness due to immune escape by the Omicron variants [

5]. More than 30 mutations in the spike gene (S) of Omicron variant were detected, in comparison to typically less than 15 in the Alpha and Delta variants [

6]. It was assumed that Omicrons enhanced infectivity was due to increased replication in the bronchi, while its reduced severity was due to reduced penetration to deep lung tissue [

7].

Due to their need for systemic immunosuppression, which may impair both cellular and humoral immune responses [

8], kidney transplant recipients (KTR) as well as other organ transplant recipients show particularly high vulnerability for COVID-19 [

9]. KTR are at high risk for developing a severe disease course with high rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, acute kidney injury (AKI), and COVID-19-related mortality [

10,

11]. COVID-19-related mortality of 14-23% was reported in KTR [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], which was higher than in the general population, where approximately 1% of patients infected with COVID-19 died until October 20, 2022 [

17]. Over time, morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 declined in the general population as well as in KTR [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In KTR, previous studies showed partially conflicting results regarding the outcomes of COVID-19 during the Omicron era: on the one side, decreased mortality was demonstrated uniformly, on the other side, variable rates of morbidity and hospitalization were reported [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Since Omicron variants showed increased immune escape, the protective effect of vaccination in KTR during the Omicron era could be reduced.

Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to report data on COVID-19 disease course and outcomes, as well as to analyze the protective effect of the vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in KTR depending on the predominant variant of concern (VoC).

2. Materials and Methods

Data collection and extraction

As a main source and interface for data collection, we used our proprietary electronic health record (EHR) TBase that is fully integrated into the data Infrastructure of Charité and enables convenient data acquisition from various data sources [

26]. For the investigation of missing data the EHR of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (SAP Deutschland SE & Co. KG, Walldorf, Germany) and additional internal databases and medical records were used.

Records of KTR infected with SARS-CoV-2, as well as further data were identified and extracted using Microsoft Access 2016 (Version 16.0) applying queries with specific criteria. The following data were extracted: patient age, sex, date of the last kidney transplantation, dates of infection and reinfection with SARS-CoV-2, dates of COVID-19-related hospital admission and discharge, ICU-admission, incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) as defined by KDIGO, date of death, number of vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2, and immunosuppressive medication at the time of infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Since no routine genetic sequencing was performed and therefore exact determination of the causative VoC was not feasible, we chose an indirect definition of VoC. In Germany, clear predominance of Omicron cases occurred on January 10, 2022 [

27]. Consequently, infection before that date was defined as pre-Omicron era, and afterwards as Omicron era. Over the course of the pandemic the following vaccines were administered: BNT162b2 (Comirnaty, BioNTech/Pfizer, Mainz, Germany), mRNA-1273 (Spikevax, Moderna Biotech, Madrid, Spain), ChAdOx1-S (AZD1222, AstraZeneca, Södertälje, Sweden), or Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson, Janssen, Beerse, Belgium) [

28]. Patients who received at least one vaccine dose before infection, were defined as being vaccinated.

Analytical approach

Our primary endpoint was COVID-related hospitalization. Secondary endpoints were COVID-19-related death, AKI, and ICU-admission.

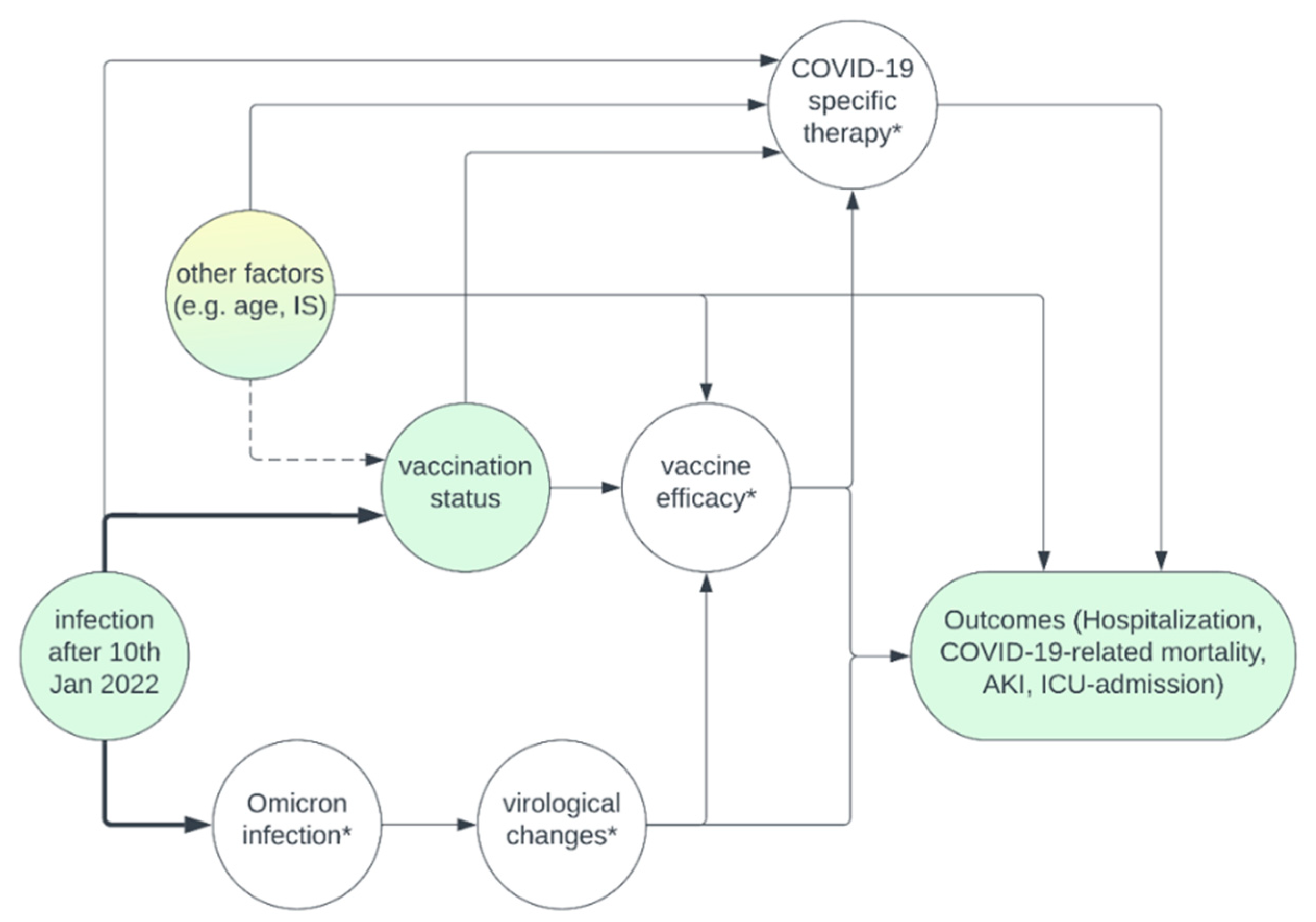

The causal directed acyclic graphs (DAG) in

Figure 1 summarizes our assumptions regarding the causal relationship of important measured and unmeasured variables, which is discussed in detail in Item A1.

No imputation methods were used, and complete case analysis was performed.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0.1.0). First, we describe the frequency of each outcome depending on era of infection and vaccination status. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk-test and compared using binomial logistic regression analysis, Mann-Whitney-U-test and Spearman´s correlation. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared-test. Based on the assumptions above and the measured variables available, we included age, immunosuppression at the time of infection, time since transplantation, and era of infection as potential confounders when estimating the effect of vaccination on COVID-19 outcomes (hospitalization, COVID-19-related mortality, AKI, ICU-admission) by performing multinomial logistic regression. A p-value of 0.05 or less (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

The ethics committee of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved this study (EA1/030/22).

3. Results

From approximately 2500 KTR followed-up at our institution [

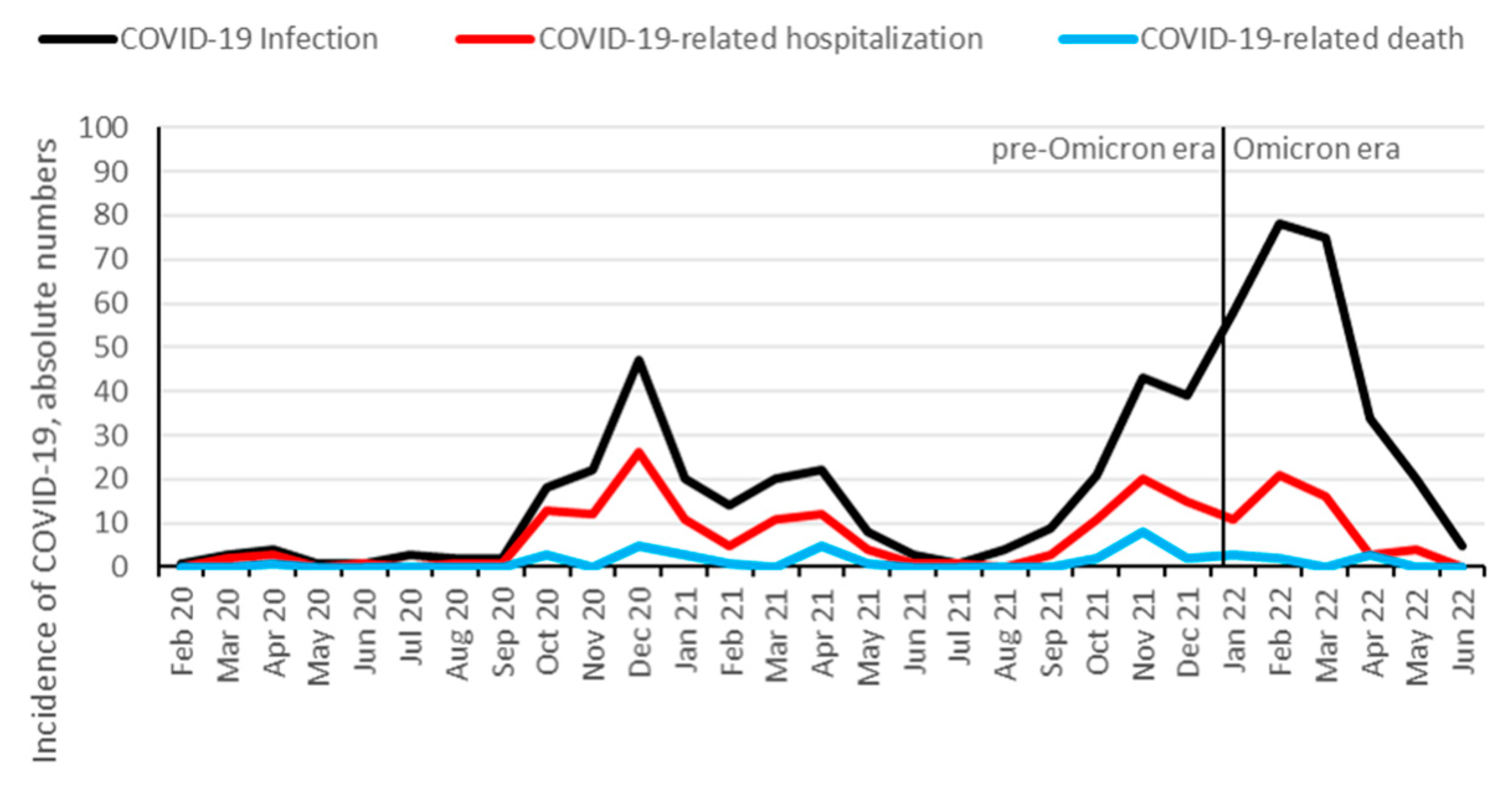

29], 578 (23%) were identified to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 between February 1, 2020 and July 1, 2022. 208 KTR (36%) were hospitalized, and 39 (7%) died from COVID-19. Additionally, 10 patients died from other causes than COVID-19: infection (3 patients), malignancy (2 patients), sudden death (2 patients), and hemorrhage (3 patients). 338 (58%) KTR were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 prior to the infection, with a median number of 3 vaccination doses. The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 started to decrease at the end of the Delta wave in November and December 2021, and further decreased after Omicron variant became dominant (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Infection, hospitalization and mortality trends, as well as demographics, course of disease and outcomes of COVID-19 are detailed in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and

Table 1, respectively.

At our center, 317 (55%) and 261 (45%) infections occurred at the pre-Omicron and Omicron era, respectively. Hospitalization rate decreased from 49% to 21% from pre-Omicron to Omicron era (p<0.001), and mortality decreased from 10% to 3% (p<0.001). Likewise, the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU decreased from 18% to 7% (p<0.001) and the number of patients with AKI decreased from 21% to 13% (p=0.022). The differences in disease course and outcomes between pre-Omicron and Omicron eras are summarized in

Table 2.

Overall, 240 patients were not vaccinated before the infection with SARS-CoV-2, of which 205 (85%) were infected during the pre-Omicron and 35 (15%) during the Omicron era. Patients, who were vaccinated before infection showed reduced reinfection rate (2% vs 8%, p=0.002), reduced hospitalization rate (24% vs 53%, p<0.001), reduced mortality rate (4% vs. 10%, p=0.003), were less likely to be admitted to the ICU (9% vs. 17% p=0.008), and were less likely to develop AKI (11% vs. 28%, p<0.001) in comparison to unvaccinated patients.

Table 3 summarizes the data on COVID-19 disease course and outcomes depending on vaccination status. The protective effects of vaccination were more pronounced for Omicron era than for the pre-Omicron era, which is summarized in

Table 4. Unvaccinated patients infected in the Omicron era show mortality (9% vs. 11%) and morbidity (hospitalization 52% vs. 54%, ICU-admission 12% vs. 18%) comparable to the pre-Omicron era, while vaccinated patients had improved outcomes, especially in the Omicron era with respect to mortality (2%) and morbidity (hospitalization 16%, ICU-admission 6%). A logistic regression demonstrated that the number of vaccination doses was inversely correlated with mortality (OR 0.71, 95% CI [0.56 - 0.89]), hospitalization (OR 0.65, 95% CI [0.58 - 0.73]), ICU-admission (OR 0.76, 95% CI [0.65 - 0.90]) and AKI (OR 0.73, 95% CI [0.63 - 0.84]).

Figure 4 demonstrates the changes of hospitalization incidence with the increasing number of vaccination doses (applied before the first infection with SARS-CoV-2).

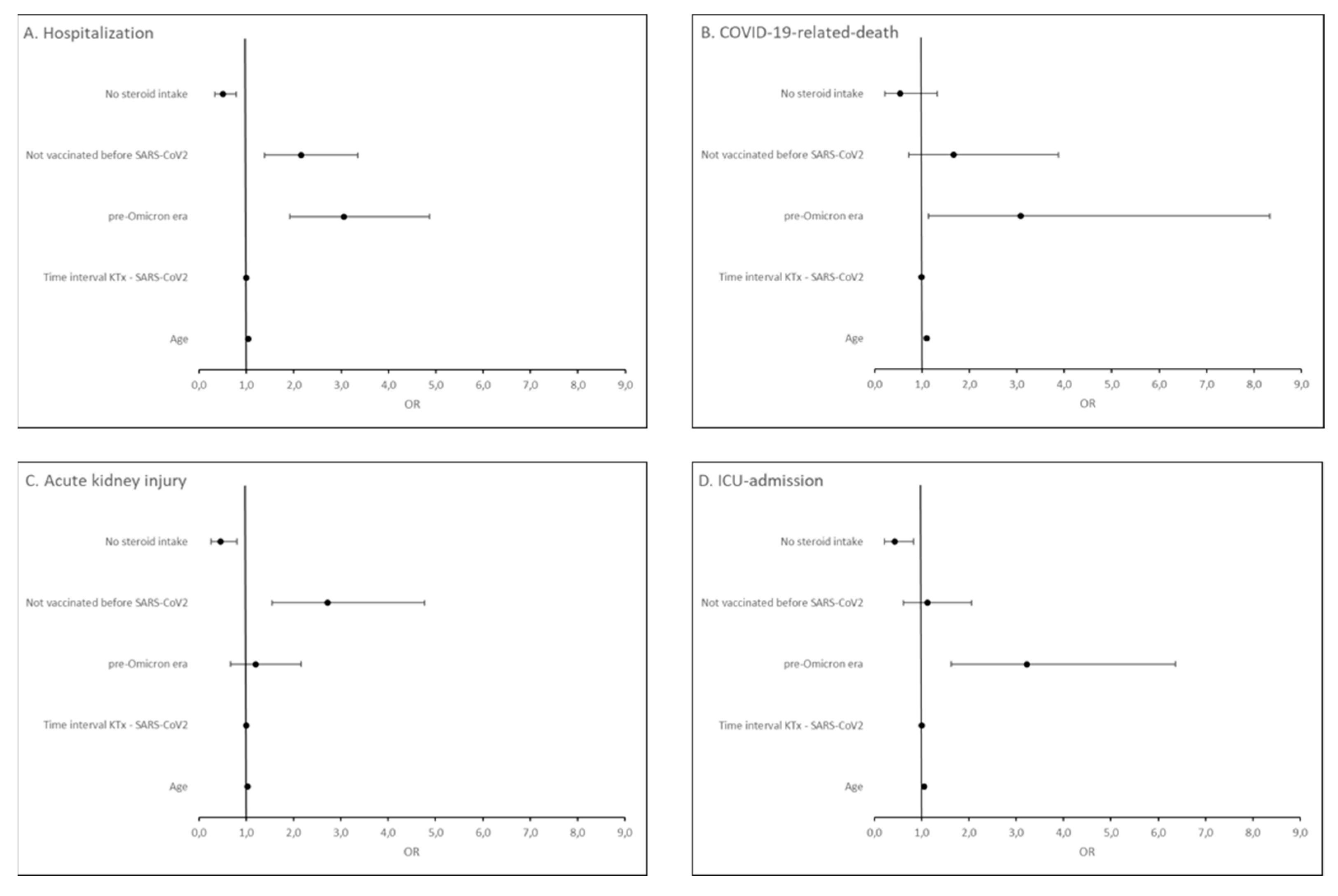

To estimate the effect of vaccination on COVID-19-related outcomes, we adjusted for potential confounding due to era of infection, age, immunosuppression, and time since transplantation (cf.

Figure 1, and Item S1) in the multivariable regression. We found that being unvaccinated (OR = 2.15, 95% CI [1.38, 3.35]), infection in the pre-Omicron era (OR = 3.06, 95% CI [1.92, 4.87]) and higher patient age (OR = 1.04, 95% CI [1.03, 1.06]) were independent risk factors for COVID-19 hospitalization. For COVID-19-related-death, only infection in the pre-Omicron era (OR = 3.08, 95% CI [1.14, 8.33]) and higher patient age (OR = 1.10, 95% CI [1.06, 1.14]) were independent risk factors. Being unvaccinated (OR = 2.72, 95% CI [1.55, 4.77]) and higher patient age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [1.02, 1.05]) were independent risk factors for COVID-19-related acute kidney injury. For ICU-admission, infection in the pre-Omicron era (OR = 3.22, 95% CI [1.63, 6.37]) and higher patient age (OR = 1.06, 95% CI [1.03, 1.08]) were independent risk factors. Steroid-free immunosuppressive regimen was found to be a protective factor both against hospitalization for COVID-19 (OR = 0.51, 95% CI [0.33, 0.79]), COVID-19-related acute kidney injury (OR = 0.45, 95% CI [0.26, 0.80]) and ICU-admission (OR = 0.43, 95% CI [0.22, 0.83]) (

Figure 5).

We furthermore analyzed, the rejection rates in both eras. In the pre-Omicron era, 88 rejection episodes occurred in 1.94 years observation period, while in the Omicron era, 28 rejection episodes occurred in 0.47 years observation period. Based on the population size of 2500 patients, the rejection rates were 1.81/100 patient years in the pre-Omicron era and 2.38/100 patients years in the Omicron era. In the same time, a small increase in biopsies occurred (5.5 biopsies/100 patient years in the pre-Omicron era vs. 7.2 biopsies/100 patient years in the Omicron era).

4. Discussion

In the present article, we show that hospitalization rate and COVID-19-related mortality and morbidity in KTR with COVID-19 decreased since the beginning of the pandemic, but especially after the Omicron-variant became dominant and a higher proportion of patients was vaccinated. We further show that both infection in the pre-Omicron era and being unvaccinated are independent risk factors for COVID-19-related hospitalization in KTR. Other factors affecting disease severity, assessed by hospitalization and COVID-19-related-death, included patient age, and steroid intake.

Additionally, the number of vaccinations was inversely correlated with morbidity and mortality, further underlining the protective effect of vaccination in KTR.

These findings are in line with observations in the general population, where both, vaccination and Omicron variant reduced the risk of severe COVID-19, independently [

5]. Within our cohort, we could also confirm that patient age and steroid intake pose risk factors for severe COVID-19, which has been described before in the general population as well as in other cohorts of KTR [

22,

30,

31,

32].

Our findings highlight that mortality and morbidity in unvaccinated KTR remains unchanged after Omicron dominance, underlining the ongoing need for vaccination or alternative immunization strategies in this vulnerable group of patients [

33]. Vaccination significantly reduced the rate of hospitalization and disease-specific morbidity and mortality during the Omicron era.

Reinfection rate in patients with COVID-19 has not been studied before, probably due to the rather low frequency of reinfections and small cohorts. We found the reinfection rate to be strongly associated with vaccination status, with the majority of reinfections occurring in unvaccinated patients, which is in line with the existing literature for the general population [

34,

35]. The overall infection rate in KTR was smaller (23%) than for the general population, where approximately 32% were infected until June 17, 2022, according to [

36]. Since the estimated number of undetected cases is probably higher in the general population, where testing is less likely to be performed in mild cases, we hypothesize that KTR are more cautious and avoided potential infections more successfully than the general population.

Rejection rates were slightly increased in the Omicron era in comparison to the pre-Omicron era, which is mostly explained by an increase in biopsies performed. This suggests that virological changes did not influence rejection rates in KTR, but that admission policies due to institutional restrictions and patient preferences were more important.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the one of the first studies to analyze disease outcomes in KTR during the Omicron era. The incidence of COVID-19 and clinical outcomes after infection were assessed in a large cohort of closely monitored KTR with granular data on outcome and vaccination status. Since most KTR with COVID-19 were followed up at our institution using a telemedicine approach, and were hospitalized at our center if necessary, the ground truth of the underlying data on hospitalization, ICU-admission, AKI and mortality is high [

37].

The major limitation is that therapeutic measures, such as treatment with monoclonal antibodies, or antiviral therapies like remdesivir have not been included into our analysis [

38,

39]. Consequently, the decrease in disease severity is not solely explained by vaccination and virological changes, but in part due to increased availability and use of therapeutic agents. Another limitation concerns the power of this study. Especially with respect to mortality, the event rate was rather low (n=39), which reduces the reliability of the results from multivariable analysis for this endpoint.

5. Conclusions

Disease severity and mortality from COVID-19 are substantially reduced in vaccinated KTR infected during the Omicron era. Unvaccinated KTR show high mortality and morbidity independent of the causative variant..

Author Contributions

data analysis, paper concept, writing of the paper, M. M..; paper concept, writing of the paper, patient treatment, data entry, B. O.; paper concept, patient treatment, data entry, reviewing the final manuscript, K. B. and F. H.; patient treatment, data entry, reviewing the final manuscript, G. E., M. G. N., E. S., F. B., M. C., W. D., E. H., N. K., L. L., C. L., H. S. H., J. W., U. W. and B. Z.

Institutional Review Board Statement

the ethics committee of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved this study (EA1/030/22).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Item A1. Explanation of the causal assumptions.

Of greatest importance is the confounding due to “infection after 10th Jan 2022”, which is equivalent to the definition of Omicron vs. pre-Omicron era. This variable influences the vaccination status (at the time of infection), since the likelihood of being vaccinated increased over time, and it influences the causative VoC, which through an unmeasured mediator (virological changes) is suspected to influence our outcomes. To a lesser extent, it influences the availability of COVID-19 specific therapies. While most of these therapies were approved before that date (remdesivir on July 2, 2020, and casirivmab/indevimab on November 11, 2021), especially the use of monoclonal antibodies became more common before and short after Omicron dominance with the availability of sotrovimab, and tixagevimab/cilgavimab. Therefore, we need to adjust for era of infection when determining the effect of vaccination on the outcomes.

Whether other factors such as patient age, time since transplantation, and immunosuppressive medication at the time of infection influence the vaccination status, is debatable. On the one hand, one could argue that all patients independent of these factors should be vaccinated and that there is no causal relationship. Otherwise, it is at least conceivable that e.g. patients with esoteric beliefs are more likely to take less immunosuppressive medication, and being unvaccinated. Under such circumstances, adjusting for the immunosuppressive medication could eliminate some of the confounding caused by an unmeasured variable “esoteric beliefs”. Since we do not cause selection bias by adjusting for variables such as age, time since transplantation and immunosuppressive medication, and they are likely to influence our outcomes, we decided to adjust for these variables in the multivariable regression analysis. Furthermore, there are unmeasured variables such as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) that we did not adjust for, which remain a potential cause for confounding [

28,

40].

References

- Navari, Y.; Bagheri, A.B.; Rezayat, A.A.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Najafi, S.; Barzegary, A.; Asadollahi-Amin, A. Mortality risk factors in kidney-transplanted patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and regression analysis. Heal. Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kun, A.; Hubai, A.G.; Král, A.; Mokos, J.; Mikulecz, B. .; Radványi,. Do pathogens always evolve to be less virulent? The virulence–transmission trade-off in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Biol. Futur. 2023, 74, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiola-Pastrana, I.R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Life-Basel 2022, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Smith, D.M.; Choi, J.Y. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant of Concern: Everything You Wanted to Know about Omicron but Were Afraid to Ask. Yonsei Med. J. 2022, 63, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, T.; et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet 2022, 399, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.X.; et al. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Omicron diverse spike gene mutations identifies multiple inter-variant recombination events. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, K.P.Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature 2022, 603, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrezenmeier, E.; et al. Temporary antimetabolite treatment hold boosts SARS-CoV-2 vaccination-specific humoral and cellular immunity in kidney transplant recipients. Jci Insight 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.H.; Solera, J.T.; Hu, Q.; Hall, V.G.; Arbol, B.G.; Hardy, W.R.; Samson, R.; Marinelli, T.; Ierullo, M.; Virk, A.K.; et al. Homotypic and heterotypic immune responses to Omicron variant in immunocompromised patients in diverse clinical settings. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffin, E.; Candellier, A.; Vart, P.; Noordzij, M.; Arnol, M.; Covic, A.; Lentini, P.; Malik, S.; Reichert, L.J.; Sever, M.S.; et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and haemodialysis patients: a comparative, prospective registry-based study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 2094–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera, J.T., et al., Impact of Vaccination and Early Monoclonal Antibody Therapy on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outcomes in Organ Transplant Recipients During the Omicron Wave. Clinical Infectious Diseases: p. 8.

- Kremer, D.; Pieters, T.T.; Verhaar, M.C.; Berger, S.P.; Bakker, S.J.; van Zuilen, A.D.; Joles, J.A.; Vernooij, R.W.; van Balkom, B.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients: Lessons to be learned. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 3936–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-J.; Kuo, G.; Lee, T.H.; Yang, H.-Y.; Wu, H.H.; Tu, K.-H.; Tian, Y.-C. Incidence of Mortality, Acute Kidney Injury and Graft Loss in Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsomer, R.; Kuypers, D. COVID-19 and solid organ transplantation: Finding the right balance. Transplant. Rev. 2022, 36, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devresse, A.; et al. Immunosuppression and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation Direct 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, A.M.; Gardiner, D.M.; Ushiro-Lumb, I.M.; Ravanan, R.M.; Forsythe, J.L.R.M. The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Solid Organ Transplantation: Two Years Into a Pandemic. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. 2020. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/.

- Dennler, U.; Geisler, F.; Spinner, C.D. Declining COVID-19 morbidity and case fatality in Germany: the pandemic end? Infection 2022, 50, 1625–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.C.; Shah, P.; Barker, L.C.; Langlee, J.C.; Freed, K.C.; Boyer, L.C.; Anderson, R.S.; Belden, M.C.; Bannon, J.M.; Kates, O.S.M.; et al. COVID-19 Clinical Outcomes in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients During the Omicron Surge. Transplantation 2022, 106, e346–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, D.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the kidney community: lessons learned and future directions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M.; et al. Outcome of COVID-19 in Kidney Transplant Recipients Through the SARS-CoV-2 Variants Eras: Role of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibodies. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjan, S., et al., Is the Omicron variant truly less virulent in solid organ transplant recipients? Transplant Infectious Disease: p. 6.

- Banjongjit, A.; Lertussavavivat, T.; Paitoonpong, L.; Putcharoen, O.; Vanichanan, J.; Wattanatorn, S.; Tungsanga, K.; Eiam-Ong, S.; Avihingsanon, Y.; Tungsanga, S.; et al. The Predictors for Severe SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) and Pre-Omicron Variants Infection Among Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2022, 106, e520–e521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; et al. COVID-19 Infection With the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variant in a Cohort of Kidney and Kidney Pancreas Transplant Recipients: Clinical Features, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cubillo, B.; et al. Clinical Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Renal Transplant Recipients. Antibody Levels Impact in Pneumonia and Death. Transplantation 2022, 106, E476–E487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; et al. TBase - an Integrated Electronic Health Record and Research Database for Kidney Transplant Recipients. Jove-Journal of Visualized Experiments 2021, 29.

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Übersicht zu Omikron-Fällen in Deutschland 2022 [cited 2022 October 21]. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Omikron-Faelle/Omikron-Faelle.html.

- Osmanodja, B.; et al. Serological Response to Three, Four and Five Doses of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanodja, B.; Mayrdorfer, M.; Halleck, F.; Choi, M.; Budde, K. Undoubtedly, kidney transplant recipients have a higher mortality due to COVID-19 disease compared to the general population. Transpl. Int. 2021, 34, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeranki, V.; et al. The adverse effects of high-dose corticosteroid on infectious and non-infectious sequelae in renal transplant recipients with coronavirus disease-19 in India. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, A.O.; Barbosa, S.; Anglicheau, D.; Couzi, L.; Hazzan, M.; Thaunat, O.; Blancho, G.; Caillard, S.; Sicard, A.; Registry, F.S.C.R.W.T.A.C.O.T.F.S.C.; et al. Association Between Maintenance Immunosuppressive Regimens and COVID-19 Mortality in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2022, 106, 2063–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requião-Moura, L.R.; de Sandes-Freitas, T.V.; Viana, L.A.; Cristelli, M.P.; de Andrade, L.G.M.; Garcia, V.D.; de Oliveira, C.M.C.; Esmeraldo, R.d.M.; Filho, M.A.; Pacheco-Silva, A.; et al. High mortality among kidney transplant recipients diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019: Results from the Brazilian multicenter cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.J.; Ustianowski, A.; De Wit, S.; Launay, O.; Avila, M.; Templeton, A.; Yuan, Y.; Seegobin, S.; Ellery, A.; Levinson, D.J.; et al. Intramuscular AZD7442 (Tixagevimab–Cilgavimab) for Prevention of Covid-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2188–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacco, M.E.; et al. COVID-19 vaccines reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and hospitalization: Meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacco, M.E.; et al. Risk of reinfection and disease after SARS-CoV-2 primary infection: Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Gesamtübersicht der pro Tag ans RKI übermittelten Fälle und Todesfälle. 2022 [cited 2022 October 19]. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Daten/Fallzahlen_Gesamtuebersicht.html.

- Duettmann, W.; et al. Digital Home-Monitoring of Patients after Kidney Transplantation: The MACCS Platform. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 25.

- Holland, T.L.; et al. Tixagevimab-cilgavimab for treatment of patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigel, J.H.; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19-Final Report. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of convalescents boosts neutralization capacity against SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron that can be predicted by anti-S antibody concentrations in serological assays. medRxiv, 2022: p. 2022.01.17.22269201.

Figure 1.

Causal diagram summarizing the assumptions underlying the analysis. Yellow – unmeasured variables, green – measured variables, *unmeasured mediators. Adjusting for era of infection eliminates confounding that is caused by time of infection on vaccination status. Among “other factors”, some variables such as age, immunosuppressive medication, and transplant age were measured, and could be adjusted for during multivariable regression to eliminate potential confounding. Other variables such as estimated glomerular filtration rate are unmeasured and remain a potential source of confounding. COVID-19 specific therapies were not assessed, but since they are not a cause for vaccination status, adjustment is not necessary. Assessment of the unmeasured mediators “virological changes” or “vaccine efficacy” is not necessary to estimate the effect of vaccination on our outcomes either.

Figure 1.

Causal diagram summarizing the assumptions underlying the analysis. Yellow – unmeasured variables, green – measured variables, *unmeasured mediators. Adjusting for era of infection eliminates confounding that is caused by time of infection on vaccination status. Among “other factors”, some variables such as age, immunosuppressive medication, and transplant age were measured, and could be adjusted for during multivariable regression to eliminate potential confounding. Other variables such as estimated glomerular filtration rate are unmeasured and remain a potential source of confounding. COVID-19 specific therapies were not assessed, but since they are not a cause for vaccination status, adjustment is not necessary. Assessment of the unmeasured mediators “virological changes” or “vaccine efficacy” is not necessary to estimate the effect of vaccination on our outcomes either.

Figure 2.

Absolute numbers of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality over time among KTR. Data are aggregated per month from February 2020 until June 2022. Omicron dominance occurred on January 10, 2022.

Figure 2.

Absolute numbers of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality over time among KTR. Data are aggregated per month from February 2020 until June 2022. Omicron dominance occurred on January 10, 2022.

Figure 3.

Hospitalization and mortality rate of COVID-19 among KTR. Data are aggregated per month from February 2020 until June 2022. Omicron dominance occurred on January 10, 2022. During low incidence periods from May 2020 – August 2020, and June 2021 – August 2021, higher fluctuations in hospitalization rate were observed.

Figure 3.

Hospitalization and mortality rate of COVID-19 among KTR. Data are aggregated per month from February 2020 until June 2022. Omicron dominance occurred on January 10, 2022. During low incidence periods from May 2020 – August 2020, and June 2021 – August 2021, higher fluctuations in hospitalization rate were observed.

Figure 4.

Distribution of hospitalization incidence depending on the number of vaccination doses.

Figure 4.

Distribution of hospitalization incidence depending on the number of vaccination doses.

Figure 5.

Forest plot summarizing the odds ratios of steroid intake, vaccination status, era of infection, time since transplantation, and patient age for hospitalization (A), COVID-19-related-death (B), acute kidney injury (C) and ICU-admission (D) in KTR with COVID-19 from February 2020 until June 2022.

Figure 5.

Forest plot summarizing the odds ratios of steroid intake, vaccination status, era of infection, time since transplantation, and patient age for hospitalization (A), COVID-19-related-death (B), acute kidney injury (C) and ICU-admission (D) in KTR with COVID-19 from February 2020 until June 2022.

Table 1.

Demographics of KTR, COVID-19 disease course and outcomes

Table 1.

Demographics of KTR, COVID-19 disease course and outcomes

| KTR infected with COVID-19, n |

|

|

578 |

| |

Reinfection, n (%) |

|

|

25 (4) |

| Males, n (%) |

|

|

|

355 (61) |

| Median age in years (IQR) |

|

|

|

54,17 (19,24 - 85,57) |

| Median time post-KTx to COVID-19 in months (IQR) |

|

101 (0 - 1463) |

| Vaccination before the infection, n (%) |

|

338 (58) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy at COVID-19 diagnosis |

|

| |

Mycophenolic acid, n (%) |

|

|

481 (83) |

| |

Tacrolimus, n (%) |

|

|

379 (66) |

| |

Cyclosporine, n (%) |

|

|

110 (19) |

| |

Steroids, n (%) |

|

|

|

373 (65) |

| |

Belatacept, n (%) |

|

|

|

27 (5) |

| |

mTOR inhibitors, n (%) |

|

|

14 (2) |

| |

Azathioprine, n (%) |

|

|

18 (3) |

| |

Patients with missing data about IS, n (%) |

|

35 (6) |

| COVID-19 clinical course and management |

|

|

| |

Acute kidney injury |

|

|

103 (18) |

| |

Hospitalization, n (%) |

|

|

208 (36) |

| |

|

Median duration in days (IQR) |

|

11 (1 - 123) |

| |

ICU-admission, n (%) |

|

|

73 (13) |

| COVID-19 outcomes |

|

|

|

|

| |

Death, n (%)1

|

|

|

|

39 (7) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 COVID-19-related-death;

IQR – interquartile range;

KTx – kidney transplantation

KTR - kidney transplant recipients;

IS - immunosuppression;

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Era-specific COVID-19 disease course and outcomes

Table 2.

Era-specific COVID-19 disease course and outcomes

| |

|

|

|

|

|

pre-Omicron1

|

Omicron2

|

p |

| KTR infected with COVID-19, n (%) |

|

|

317 (55) |

261 (45) |

|

| |

Reinfection, n (%) |

|

|

23 (7) |

2 (1) |

|

| Vaccination before the infection, n (%) |

|

110 (35) |

228 (87) |

|

| COVID-19 clinical course and management |

|

|

|

|

| |

Acute kidney injury |

|

|

68 (21) |

35 (13) |

0.022 |

| |

Hospitalization, n (%) |

|

|

154 (49) |

54 (21) |

< 0.001 |

| |

|

Median duration in days (IQR) |

|

12 [1-123] |

11 [1-103] |

< 0.001 |

| |

ICU-admission, n (%) |

|

|

56 (18) |

17 (7) |

< 0.001 |

| COVID-19 outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Death, n (%)3

|

|

|

|

31 (10) |

8 (3) |

0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 before Januar 10, 2022; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 from Januar 10, 2022; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 COVID-19-related-death; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| KTR – kidney transplant recipients; |

|

|

|

|

|

| IQR – interquartile range |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

COVID-19 disease course and outcomes of not vaccinated1 and vaccinated1 KTR2

Table 3.

COVID-19 disease course and outcomes of not vaccinated1 and vaccinated1 KTR2

| |

|

|

|

|

|

not vaccinated |

vaccinated |

p |

| Total, n |

|

|

|

240 |

338 |

|

| |

Reinfection, n (%) |

|

|

18 (8) |

7 (2) |

0.002 |

| |

Omicron3, n(%) |

|

|

|

35 (15) |

226 (67) |

< 0.001 |

| COVID-19 clinical course and management |

|

|

|

|

| |

Acute kidney injury |

|

|

66 (28) |

37 (11) |

< 0.001 |

| |

Hospitalization, n (%) |

|

|

128 (53) |

80 (24) |

< 0.001 |

| |

|

Median duration in days (IQR) |

|

11 (1 - 123) |

12 (1-123) |

< 0.001 |

| |

ICU-admission, n (%) |

|

|

41 (17) |

32 (9) |

0.008 |

| COVID-19 outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Death, n (%)4

|

|

|

|

25 (10) |

14 (4) |

0.003 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 prior to the SARS-CoV-2 infection;

2 Kidney transplant recipients; |

|

|

|

|

|

3 from Januar 10, 2022; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 COVID-19-related-death. |

|

|

|

|

|

| KTR – kidney transplant recipients |

|

|

|

|

|

| ICU – intensive care unit |

|

|

|

|

|

| IQR – interquartile range |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Era- and vaccination-specific COVID-19 disease outcomes

Table 4.

Era- and vaccination-specific COVID-19 disease outcomes

| |

|

|

|

|

|

pre-Omicron1

|

Omicron2

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

vaccinated |

not vaccinated |

vaccinated |

not vaccinated |

| KTR infected with COVID-19, n (%)3

|

|

|

110 (35) |

207 (65) |

228 (87) |

33 (13) |

| |

Reinfection, n (%) |

|

|

5 (5) |

18 (9) |

2 (1) |

0 (0) |

| COVID-19 outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Acute kidney injury |

|

|

16 (15) |

52 (25) |

21 (9) |

14 (42) |

| |

Hospitalization, n (%) |

|

|

43 (39) |

111 (54) |

37 (16) |

17 (52) |

| |

|

Duration in days (IQR) |

|

14 (1-123) |

11 (1-123) |

11 (1-86) |

12 (3-103) |

| |

ICU-admission, n (%) |

|

|

19 (17) |

37 (18) |

13 (6) |

4 (12) |

| |

Death, n (%)4

|

|

|

|

9 (8) |

22 (11) |

5 (2) |

3 (9) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 before Januar 10, 2022; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 from Januar 10, 2022; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 of all pre-Omicron/Omicron patients; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 COVID-19-related-death. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KTR - kidney transplant recipients;

IQR – interquartile range |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).