1. Introduction

The vestibular system is a perceptual system responsible for providing the brain with information regarding spatial orientation, head position, and motion. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in maintaining balance and stability [

1]. Despite numerous studies in various areas of medical field, the detection of vestibular disorders is an area that has not received sufficient attention yet. This study aims to fill this gap by utilizing TE as a tool to identify VS-related diseases.

Various methods are employed in the literature to identify the specific VS problem while the most popular clinical method is still the computerized dynamic posturography (CDP) [

2]. The state-of-the-art methods basically are based on utilizing classification techniques following a machine learning step where the features are extracted from gait data.

The gait data are especially used to give information about balance disorder related to different diseases. Within this context, gait analysis has emerged as a valuable tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases, providing objective measures to assess motor impairments associated with these conditions. It has been extensively utilized in the evaluation of diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and other related disorders. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of gait analysis in identifying disease-specific gait abnormalities and distinguishing between different neurodegenerative conditions. As an example, Nir Giladi et al. propose a new clinical classification scheme for gait and posture and discuss the use of gait analysis in identifying disease-specific gait abnormalities [

3]. Bovonsunthonchai et al. investigate the use of spatiotemporal gait variables in distinguishing between three cognitive status groups and discuss the potential of gait analysis as a tool for early detection of neurodegenerative conditions [

4]. Guo Yao et al. summarize researches on the effectiveness and accuracy of different gait analysis systems and machine learning algorithms in detecting Parkinson’s disease based on gait analysis [

5].

The use of gait data in the diagnosis of diseases causing imbalance extends beyond the aforementioned neurodegenerative conditions. It has also been employed in assessing balance disorders associated with dysfunction in the VS. This comprehensive analysis aids in early detection, accurate diagnosis, and monitoring of these disorders. As an example, A. R. Wagner et al. discuss how gait analysis can be used to assess vestibular-related impairments in older adults, and how these impairments can impact balance control [

6]. In [

7] Ikizoğlu and Heyderov search for significant features from IMU-sensor based data to diagnose VS disorders. In [

8] Agrawal et al. utilize wireless pressure sensors embedded in insoles along with machine learning models to predict fall risks, achieving promising results. In [

9] Schmidheiny et al. focus on the discriminant validity and test-retest reproducibility of a gait assessment in patients with vestibular dysfunction.

In this study, our aim was to utilize contemporary classification methods to extract pertinent characteristics from gait data for the purpose of diagnosing VS dysfunction sourced balance disorders. To accomplish this objective, we employed an innovative approach that involved TE value as the feature. TE offers a framework for characterizing the statistical properties of complex systems and thus, it is capable to define non-extensive systems. TE has proven to be effective in diverse domains such as physics, information theory, and economics, enabling a more comprehensive analysis and understanding of systems with long-range correlations and heavy-tailed distributions [

10]. As an example of the application of TE in the field of biomedical engineering, Zhang et al. investigate the dependency of TE of EEG data on the burst signals after cardiac arrest [

11]. Again, Tong et al. use TE of EEG signals as a measure of brain injury in their study [

12]. Considering the human gait to exhibit non-extensive behavior with long range correlations [

13,

14,

15,

16], we expected TE to be rather helpful in analyzing the balance performance of individuals. Thus, by applying TE to gait data, our objective was to capture vital information concerning the behavior and dynamics of the VS, which can contribute to the identification of related diseases.

This study is an important step within a big project which we conduct together with the audiologists from The Medical School Cerrahpaşa-Istanbul. We aim to develop a diagnosing system to identify the specific VS dysfunction-sourced disease-causing imbalance. We also aim to determine the stage of the problem. The first step in this process is the classification of the individual as healthy or suffering. For this classification we search for primary discriminative features. We collect various features which will then enter a feature reduction/selection process. According to the experience of the audiologists, these primary features are expected to be obtained from relatively short data acquisition period in order not to put the patient in stress and thus to increase the accuracy of the whole system. In [

7] we discussed the effectiveness of features obtained from IMU sensors data, where we achieved an accuracy around 90%. In [

17] we presented a feature based on insole pressure sensor data called fractal spectrum width that had an accuracy around 98% in distinguishing between the classes in the first step of the entire process. This study is also based on the same data as the latter one and looks for new features to be effective in the feature selection/reduction process. We put our accuracy threshold as 90% for any individual feature in order to step into the basket for the reduction stage.

We can briefly compile the contributions we have brought with this study as follows: Most studies have focused on features related to gait analysis such as stride time, stance time etc., which require a relatively long walking time. This study aims to shorten the data acquisition period by capturing features from short walks. Pressure data collected from wearable insole sensors are used for feature extraction. This approach allows data to be obtained in daily life, helping the patient avoid the stress of the clinical environment and potentially improving the accuracy of the diagnosis [

18,

19]. We detrend the normalized raw data, allowing to identify individual specific fluctuations around the trend, thereby increasing the accuracy. As one of our basic contributions, we propose a specific algorithm to determine the trend curve in each walking step. This process leads to better distinguish temporary imbalance from unusual walking habit.

After feature extraction, the extracted features were used to train models using classification methods. The main classification categories included Decision Trees (DT), Discriminant Analysis, Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Kernel Approximation, Ensemble, and Neural Networks.

Considering the flow of the study, the rest of the article is structured as follows: The Materials and Methods section provides comprehensive details on TE. Subsequently, in the Data Acquisition Process section, a thorough explanation is given regarding the data collection process. In the Data Processing section, the step-by-step procedures for transforming the raw data into distinct features are elaborated upon. The outcomes of the subsequent experiments are presented comparatively within the Results section. Lastly, in the Discussion section, the results are analyzed, inferences drawn, and future prospects regarding the utilization of the outcomes within the broader project are mentioned.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Entropy, Tsallis Entropy - Brief Background

Entropy is a property that is mostly used as a measure to describe the chaotic level of a dynamic system. The well-known Shannon entropy (SE) based on Boltzmann- Gibbs statistical mechanics and formulated as

is capable to describe the structure of extensive systems with short-term microscopic correlations [

20]. In (1), N is the number of microstates and

stands for the probability of the

-th microstate.

For systems with long-term interactions however, or systems presenting long-term memory effect, the effectiveness of applying SE for the abovementioned purpose decreases [

21]. At this point, forming the generalized structure of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics, the Tsallis entropy (TE) within the non-extensive statistics contributes significantly to find out the hidden information in the time series [

22].

TE has found applications in various fields, including biomedical research. In the context of biomedicine, TE has proven to be a valuable tool for analyzing complex systems and understanding the dynamics of biological processes with its main advantage to capture the non-linear and long-range dependencies present in biological systems [

12,

17].

The Tsallis entropy is formulated as

where

is a parameter to indicate the strength of the non-extensivity. This is because for two independent systems X and Y, we have

that (1 −

) is a measure of the deviation from being additive (extensive). For

we speak of sub-extensivity, whereas

points to super-extensivity [

23]. For

we have TE = SE. In (2),

is the number of possible states and

represents the probability of the

-th state. The determination of the value of the parameter

does not have specific criteria, but rather depends on the specific characteristics of the analyzed dataset [

24]. By adjusting the value of

, the entropy metric can be tailored to capture particular features inherent in the analyzed dataset.

2.2. Data Collection

We recall that the data used in this study are the same as in our previous study [

17].

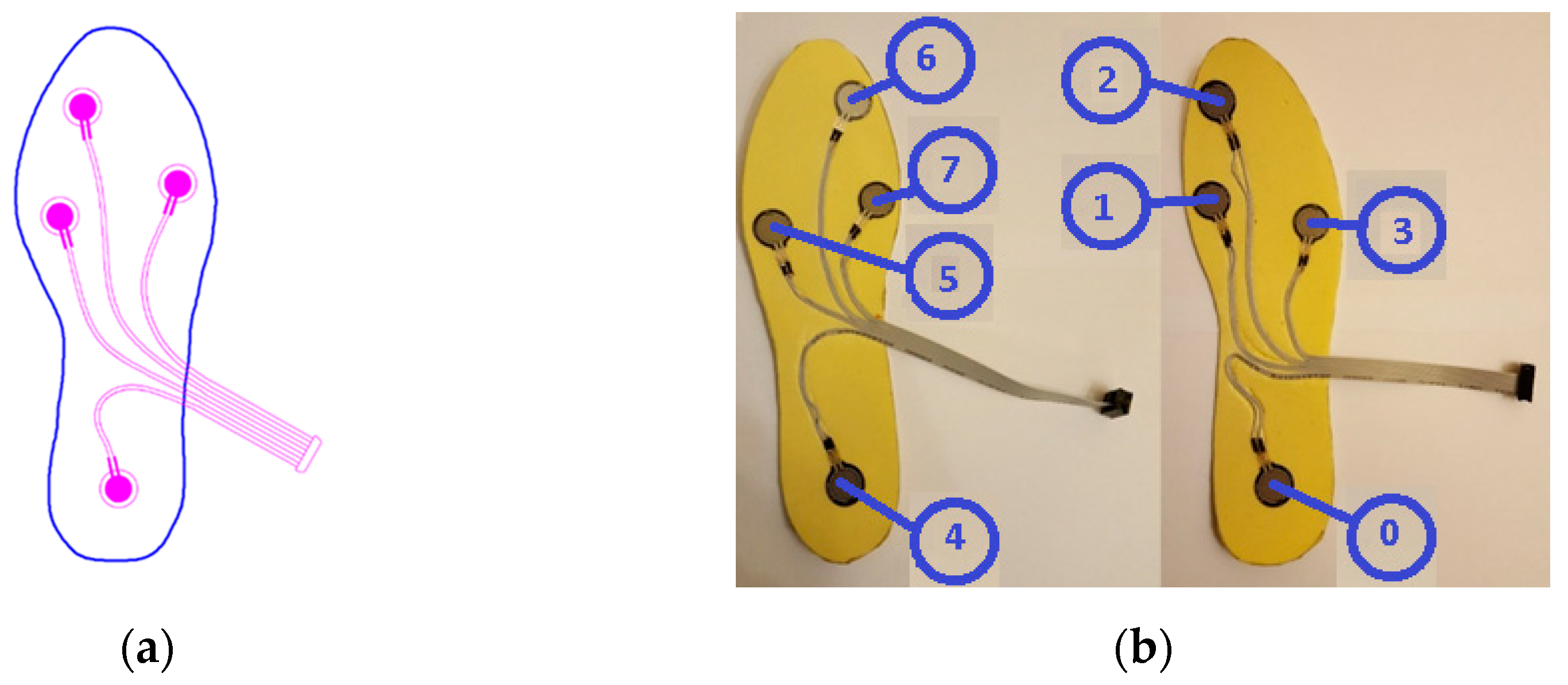

When the gait analysis studies in the literature are examined, it is seen that the distribution of weight is concentrated especially on four main points on the soles of the feet, as depicted in

Figure 1a [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Also in this study, these four points were chosen for the placement of sensors in line with the opinions of academics in the field of audiology, as acknowledged in the Acknowledgments section.

To ensure data collection without disturbing the natural walking patterns of the participants, 5 pairs of insoles with different sizes (36, 38, 40, 42, 44 - according to European Standards) were manufactured. Prior to the commencement of the experiment, the correctly sized insoles were inserted into the subjects’ shoes. For the production of the insoles, a durable and soft plastic material commonly employed in the manufacturing of orthopedic products was utilized.

Force-sensitive resistors (FSR) were chosen as pressure sensors, as they are widely used in gait analysis applications and offer several advantages [

30]. Considering the physical dimensions and the acceptable repeatability feature, the FSR402-Short tail model from Interlink was selected [

31]. The characteristics of the sensor can be found in

Table 1. The sensors on the insoles are numbered S0 to S7 as seen in

Figure 1b.

Data collection was carried out in the clinical setting of the Audiology Department at Cerrahpaşa Medical School, Istanbul University - Istanbul, Türkiye. The process was conducted in compliance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Before starting the process, approval was obtained from the Istanbul University Ethics Committee (Approval number: A-57/07.07.2015). In addition, informed consent was taken from all subjects to participate in the study. For individuals with VS problems, their conditions had already been diagnosed by the audiologists using conventional systems (Computerized Dynamic Posturography-CDP).

Data were collected on weekends to minimize the subjects’ stress and avoid interference from other nearby devices. The subjects were asked to walk the 12-meter long path twice. The first walk aimed to help them become familiar with the environment and reduce any possible stress, while the data from the second walk were used for analysis in general. In some cases, subjects walked a third time when needed as a result of the audiologists’ observations.

The pressure sensor data collected with the Arduino Mega device placed on the subjects were transferred to the laptop wirelessly via the HC-06 Bluetooth unit. Sampling was performed from all sensors simultaneously at a rate of 20 samples per second. In order to convert the force to voltage, a 1k resistor in series with the FSR served as a voltage divider. As the next step we calibrated this structure in the lab since the FSR has a highly non-linear characteristic curve. Supplying the structure by 5V DC voltage presented an average function as

where

[N] is the weight applied onto the sensor and

[V] is the output voltage. 10% deviation from the values obtained by Equation 4 was taken as the criterion that would require the relevant sensor not to be used in the experiments.

Informative data about the participants are listed in

Table 2.

The distribution of the subjects whose specific disease was detected by CDP by audiologists is given in

Table 3.

To ensure the confidentiality and privacy of all participants, their identities have been anonymized for publication of this article.

2.3. Data Processing

In order to interpret the results more accurately on the basis of the subject, the obtained data were preprocessed before feature extraction. Thus, the feature extraction process was carried out in six stages.

2.3.1. Stage 1—Framing Useful Data

We framed the useful part of the whole walk, where data corresponding to the first and last steps were extracted from the overall data. Thus, data on steps with missing dynamic behavior were excluded from the evaluation.

2.3.2. Stage 2—Determining the Intervals When the Foot Is Actively Touching the Ground

Of all gait data, only those corresponding to the time intervals during which the foot is actively touching the ground provide useful information. These intervals were determined for each foot as follows:

Each sensor data are normalized to the range 0-1 as

where

is the original/raw data and

&

represent the minimum and maximum values.

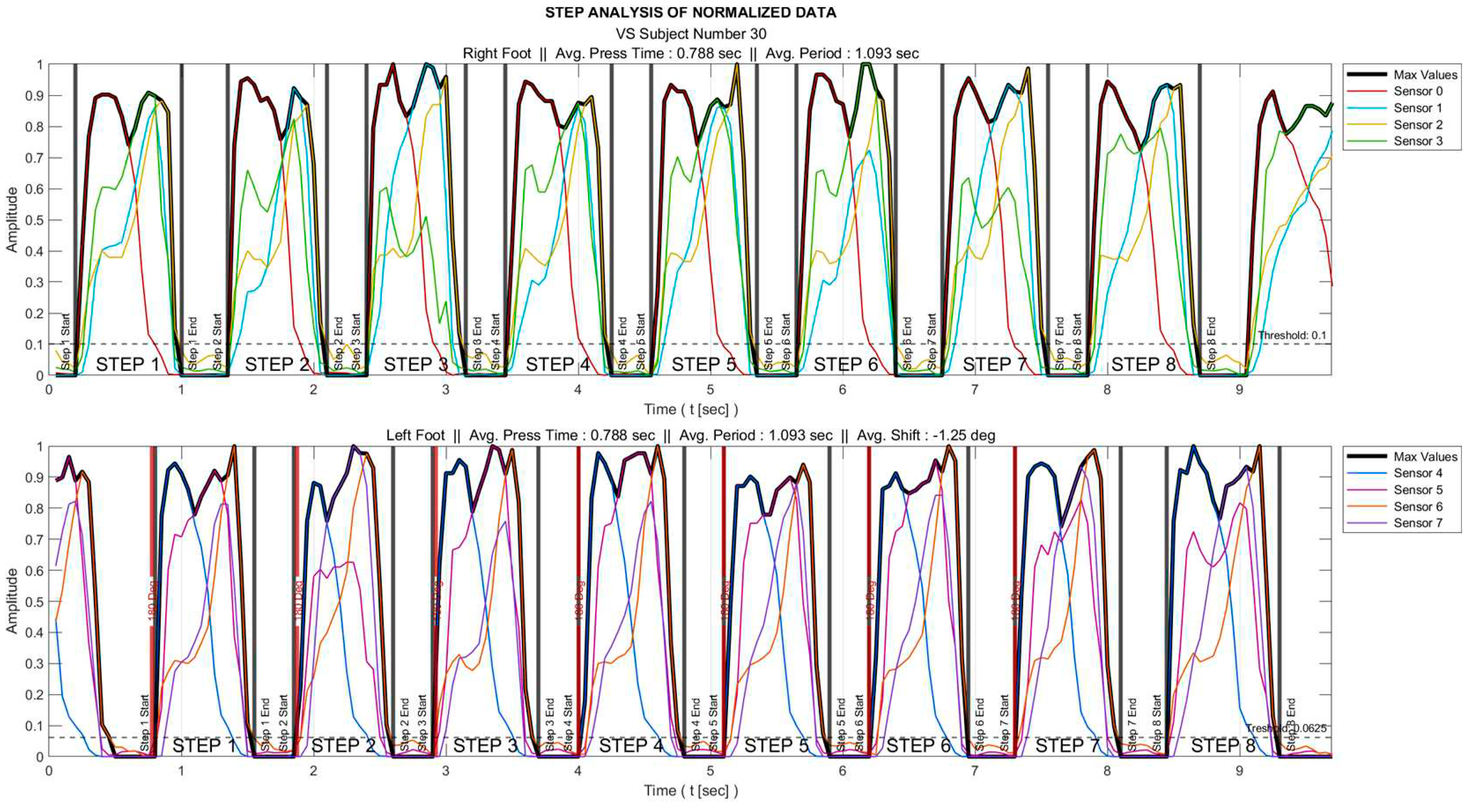

The maximum of all sensor data () is determined. As an example, for the right foot, these data are obtained as .

A threshold is set that the foot is interpreted to be in the air for the time interval where remains below this threshold value.

The process is visualized in

Figure 2 for a sample subject.

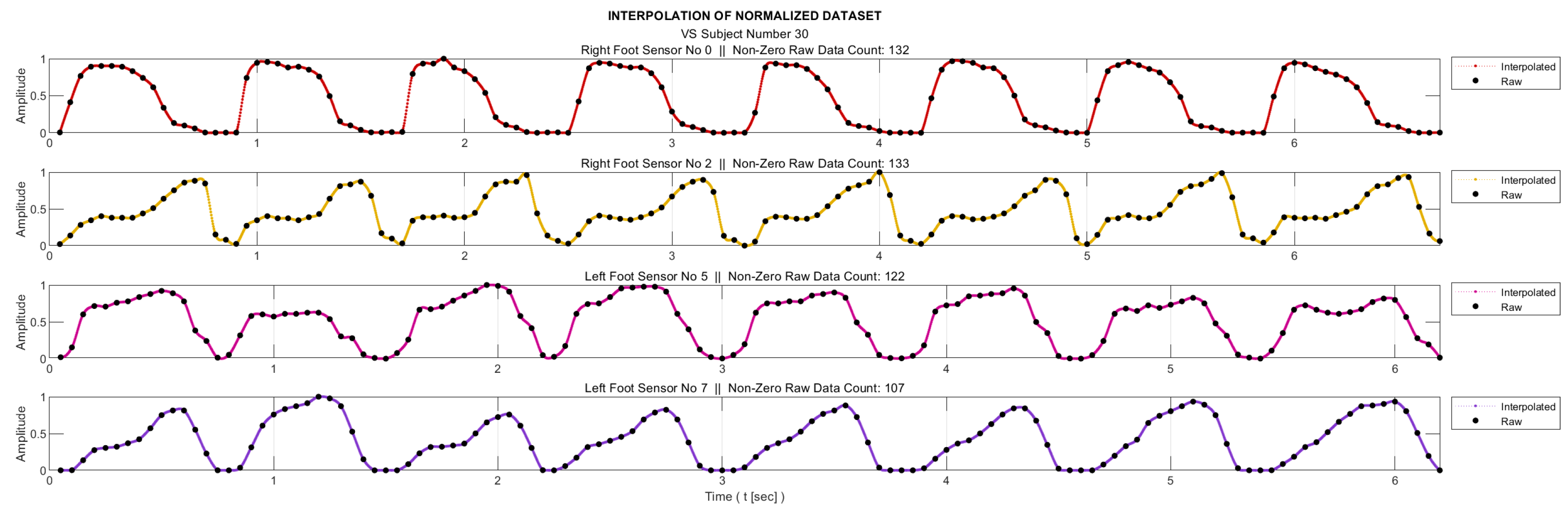

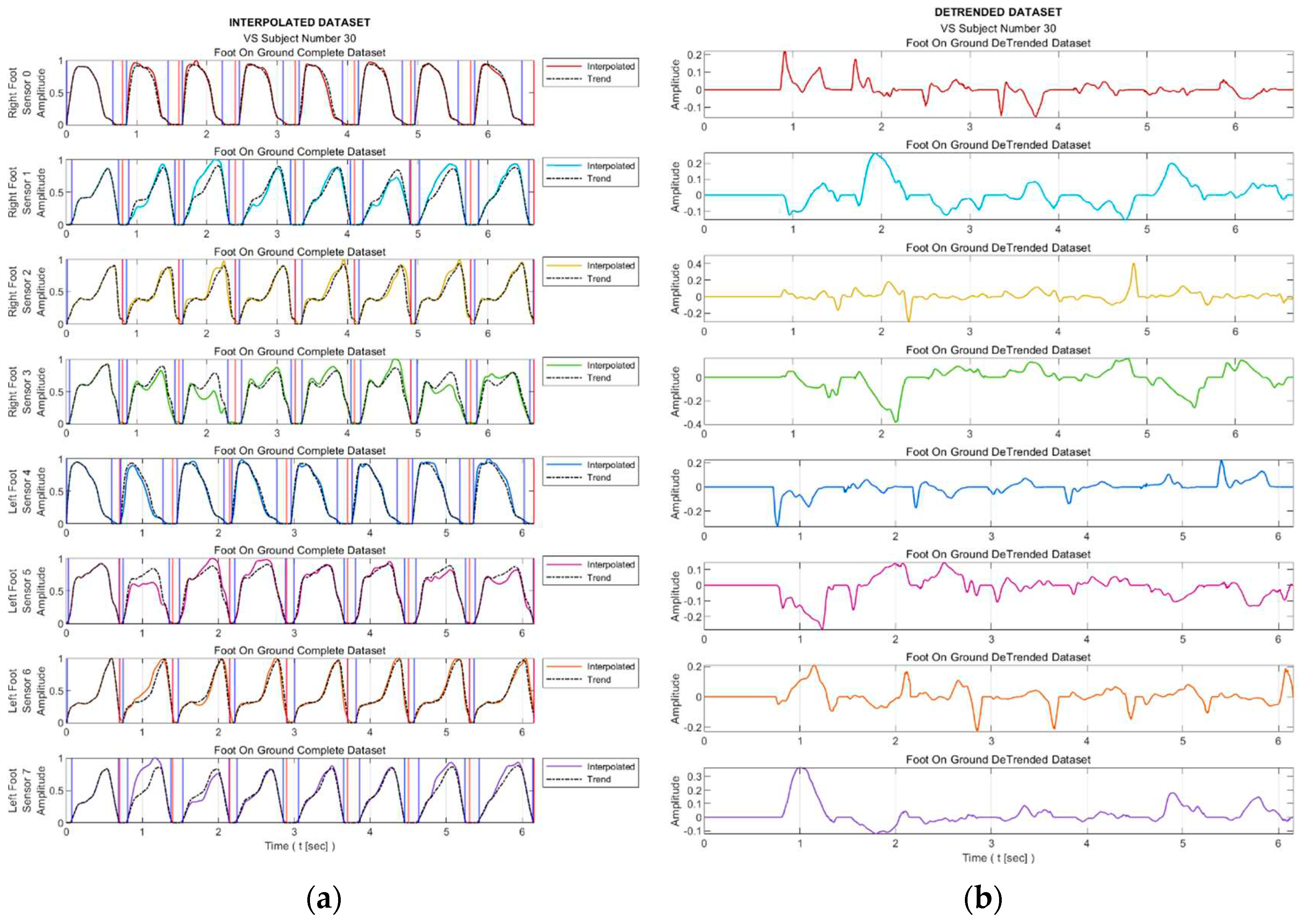

2.3.3. Stage 3—Interpolation

As mentioned in ‘Data Collection’ section, the sampling frequency for data acquisition was 20Hz. On the other hand, for meaningful entropy calculation, we need a significant number of bins in the histogram of the relevant data, as well as a sufficient number of samples in each bin. Therefore, we applied 20-fold interpolation to each sensor data. Prior to interpolation process, the segments where the feet were not in contact with the ground were removed from the data sequences. The process is illustrated in

Figure 3 for a sample subject. Linear interpolation was not preferred in order to maintain accuracy without compromising the representation of the data. Instead, the cubic Hermite interpolation method was chosen as the interpolation technique. This method provides a smoother and more accurate representation of the data while preserving its integrity [

32].

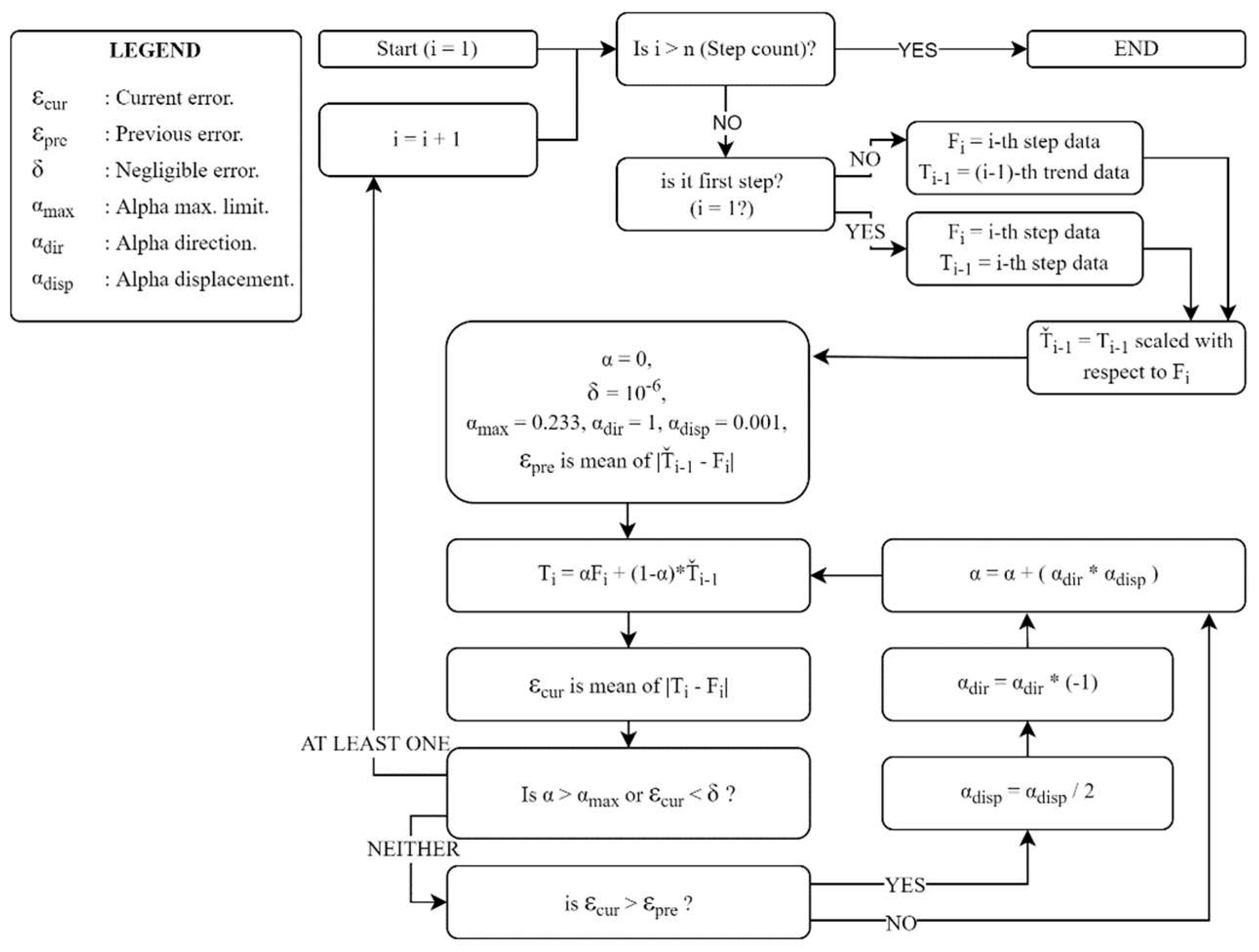

2.3.4. Stage 4—Detrending

To classify an individual as healthy or diseased, we are concerned with the deviation of the data from those corresponding to the person’s walking habit. Therefore, we first determined the trend data related to the walking habit. The process illustrated in Figure 5 can be briefly explained as follows: For each step, the trend curve of the previous step is scaled in the time axis using the ‘Nearest-neighbor interpolation’ method based on the length of the current step data, thus we equate both the current and previous step data lengths. A trend dataset is then generated for the current step i using Equation 6.

Here,

is the current-step trend data, and

stands for the current step data.

denotes the trend data whose length is scaled, and

is a coefficient indicating the degree to which the previous trend curve is approximated to the current step data set. In

Figure 4,

represents the maximum rate of change that each data point of the trend curve can exhibit from one step to the next, for which the value 0.23 was statistically determined, considering data from healthy subjects. The process is terminated when the

value reaches

or the error value defined as

falls below a threshold so that it is considered negligible. The threshold level is set as

.

Figure 5 presents the trend curves and the detrended dataset for a sample VS-diseased subject.

2.3.5. Stage 5—Tsallis Entropy Calculations

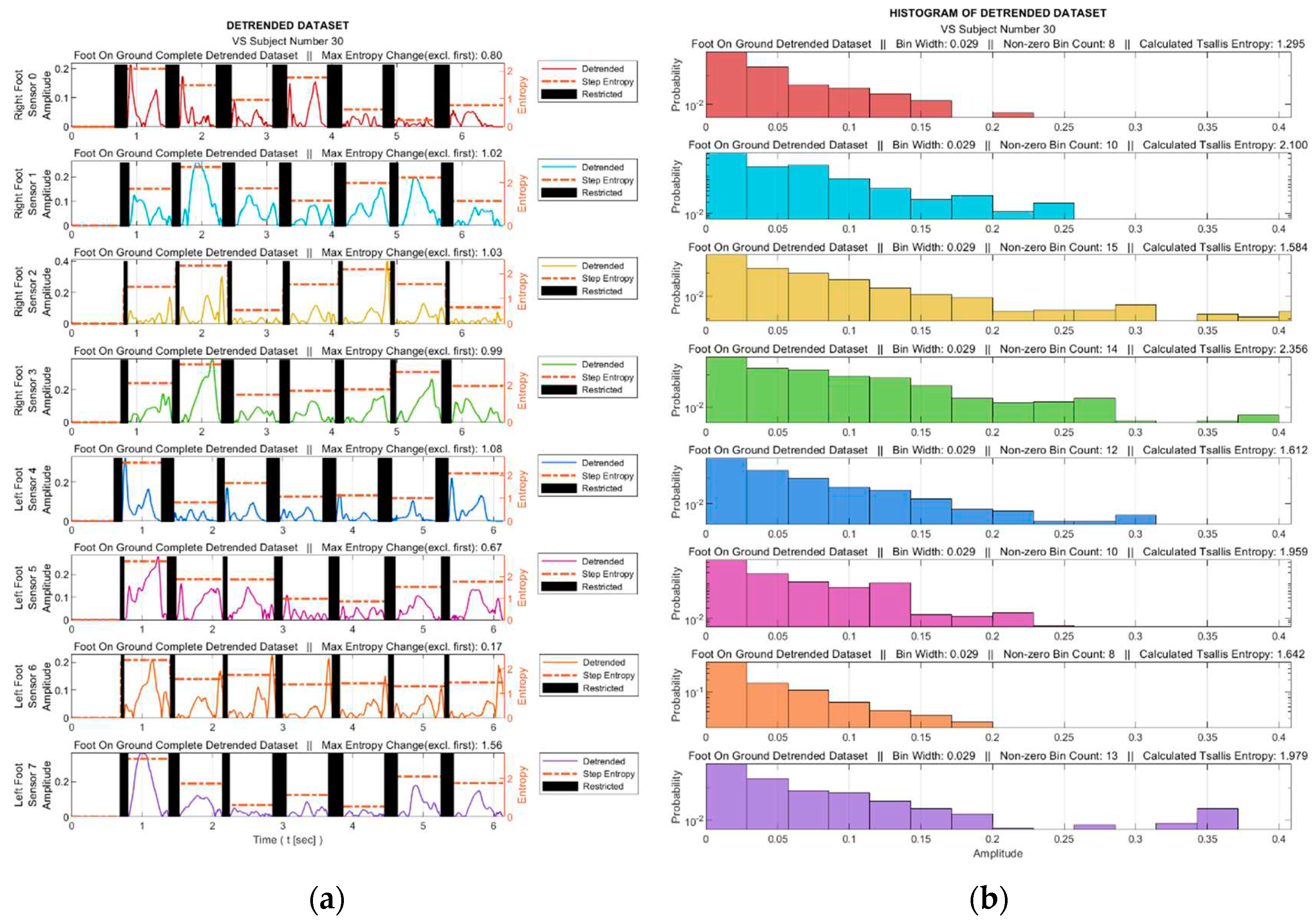

At this stage, the TE calculation was performed with the help of the histograms generated from the detrended data. The process was performed for both the entire gait data for each sensor and each step data within the gait cycle. For each sensor, the data corresponding to the intervals in which the relevant sensor is not actively used were extracted from the data set. These intervals are marked as black bar in

Figure 6a for a sample data set. Histograms were obtained from the absolute values of the detrended dataset, where the maximum number of bins was determined as 25 in order to achieve an acceptable granularity.

Figure 6b illustrates the corresponding histograms for the data set in

Figure 6a.

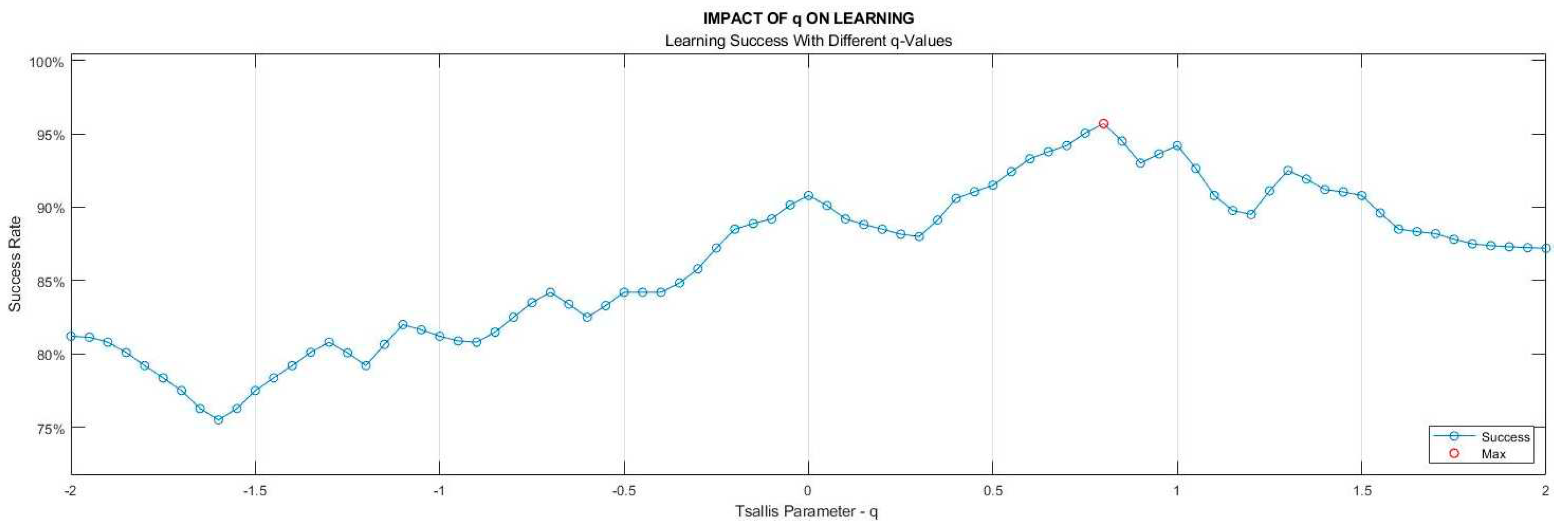

As mentioned in the Materials & Methods section, the selection of the

parameter value in TE calculation does not have a predefined criterion, it rather depends on the specific characteristics of the analyzed data set. For our data sets, the best

value to reach the highest accuracy was determined as 0.82. In the process of determining the

parameter, nine classification algorithms of learning models outlined in Stage 6 took part with a 10-fold cross-validation technique. The ratios of models attaining the highest success were employed as the benchmark. The learning success rates vs

values are depicted in

Figure 7.

Figure 6.

For a sample diseased subject (no. 30), (

a) Absolute values of the detrended data in

Figure 5b and the step-by-step TE values (Black bars indicate ranges in which the corresponding sensor is inactive), (

b) Histograms derived from the entire gait data (Sensor inactive intervals removed).

Figure 6.

For a sample diseased subject (no. 30), (

a) Absolute values of the detrended data in

Figure 5b and the step-by-step TE values (Black bars indicate ranges in which the corresponding sensor is inactive), (

b) Histograms derived from the entire gait data (Sensor inactive intervals removed).

Figure 7.

Dependency of the learning success on Tsallis parameter () value.

Figure 7.

Dependency of the learning success on Tsallis parameter () value.

2.3.6. Stage 6—Feature Extraction

As stated in the introduction, although human gait seems to have a regular pattern, the literature review reveals that we observe fluctuations in this pattern. For healthy people, these fluctuations are long-range correlated. However, this correlation weakens for people with balance problems. Thus, the TE value could be a significant measure to identify the class of individuals as healthy or diseased. In this study, we leveraged two TE-based possibilities to feature any VS dysfunction-sourced problem. One was to consider the TE value of the entire gait cycle, and the other was to examine the change in TE value from step to step. For the second case, we decided to examine the deviation of the TE value from zero, because in the ideal case it is clear that the step-to-step change of entropy for a healthy person would be zero. Thus, for this case, the data set containing the step-by-step entropy values was expanded by adding the negatives of all data values and the standard deviation of the newly created data set (

) was calculated as given by Equation 7.

In Equation 7, is the TE value of the -th step data, denotes the set of step-by-step TE values, and represents the expanded set.

We had four sensors under each foot, so, eight sensors in total. Using both the TE value of the entire gait cycle for each sensor as well as the stepwise variation of the TEs, we had a total of 16 features that served for machine learning. For the classification process we used the Matlab R2021b Classification Learner Tool (on MSI GE75 Raider 10875H). 10-fold cross validation technique was applied, where approximately 25% of the total data (from 15 subjects) was used for testing and the remainder (from 45 subjects) for training.

The process of classification training involved utilizing nine different model categories as: Decision trees (DT), discriminant analysis, logistic regression, naïve Bayes, support vector machine (SVM), k nearest neighbors (KNN), kernel approximation, ensemble and neural networks. Considering the sub-models in these categories, such as ‘Course: 4, Medium: 20, Fine: 100’ for the maximum number of splits in the decision tree category, a total of thirty-two models were involved in the process.

Among all the classifiers examined, SVM (Gaussian), KNN (cosine – k equals to 10), and Logistic regression showed the three best performances. To give brief information about these classifiers: The KNN algorithm determines the class membership of an object/vector by examining its k nearest neighbors [

29]. In this study, the k value yielding the best result has been determined to be 10. Logistic regression is a statistical model used to predict the probability of a dependent variable belonging to two or more classes in a dataset [

30]. SVM seeks to find an optimal hyperplane to separate data clusters [

31]. These three algorithms are among the most widely used in studies on biomedical signals in the literature [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

3. Results

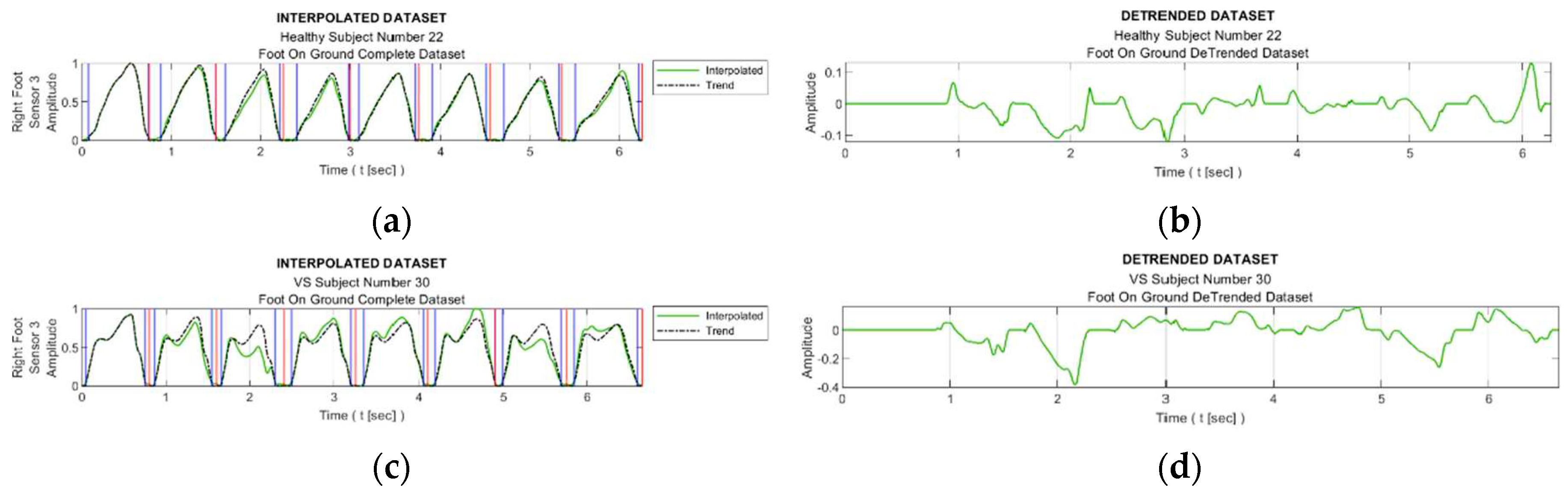

In this section, a comparative analysis is made based on data collected from both healthy and VS-diseased individuals. The comparison will commence from the detrending stage of processing the sensor data, as described in the Data Processing section.

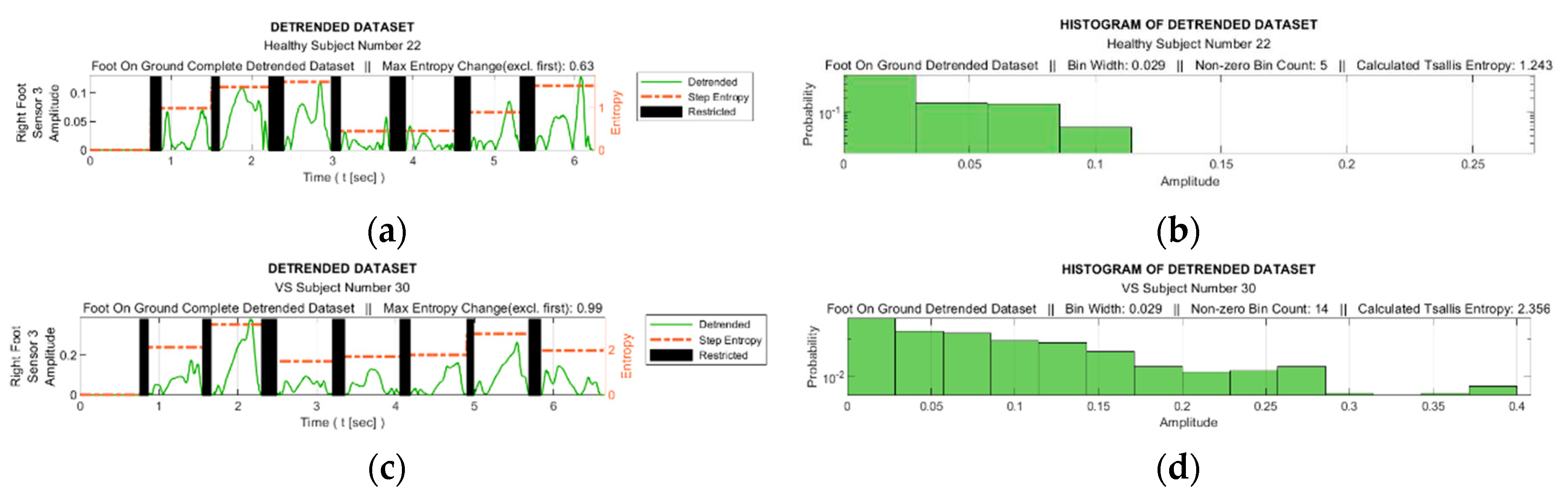

Figure 8 facilitates observing discernible variations in the exposure of sensor S3 during walking for sample healthy and diseased individuals. Additionally, it visualizes the detrended data, i.e., the difference between the step data and the trend curve.

To see the effect of the proposed trending algorithm, trend curves were created using 2nd, 3rd and 4th degree curve fitting polynomials and the results were compared. The classification accuracies obtained with the different trending methods are listed in

Table 4.

Figure 9 shows the graphs of the detrended data with absolute value taken from

Figure 8b,d and the histograms produced from this graphs. In

Figure 9a,c, the black bars indicate the inactive periods of the related sensor. For these sample subjects and sensor data, the maximum step-by-step change of the TE value for the healthy subject is calculated as 0.63, whereas it is 0.99 for the VS-diseased person. The TE value for the entire gait cycle is calculated as 1.243 for the healthy individual, and 2.356 for the suffering subject. In

Table 5 the TE values are listed for these sample subjects for all sensor data.

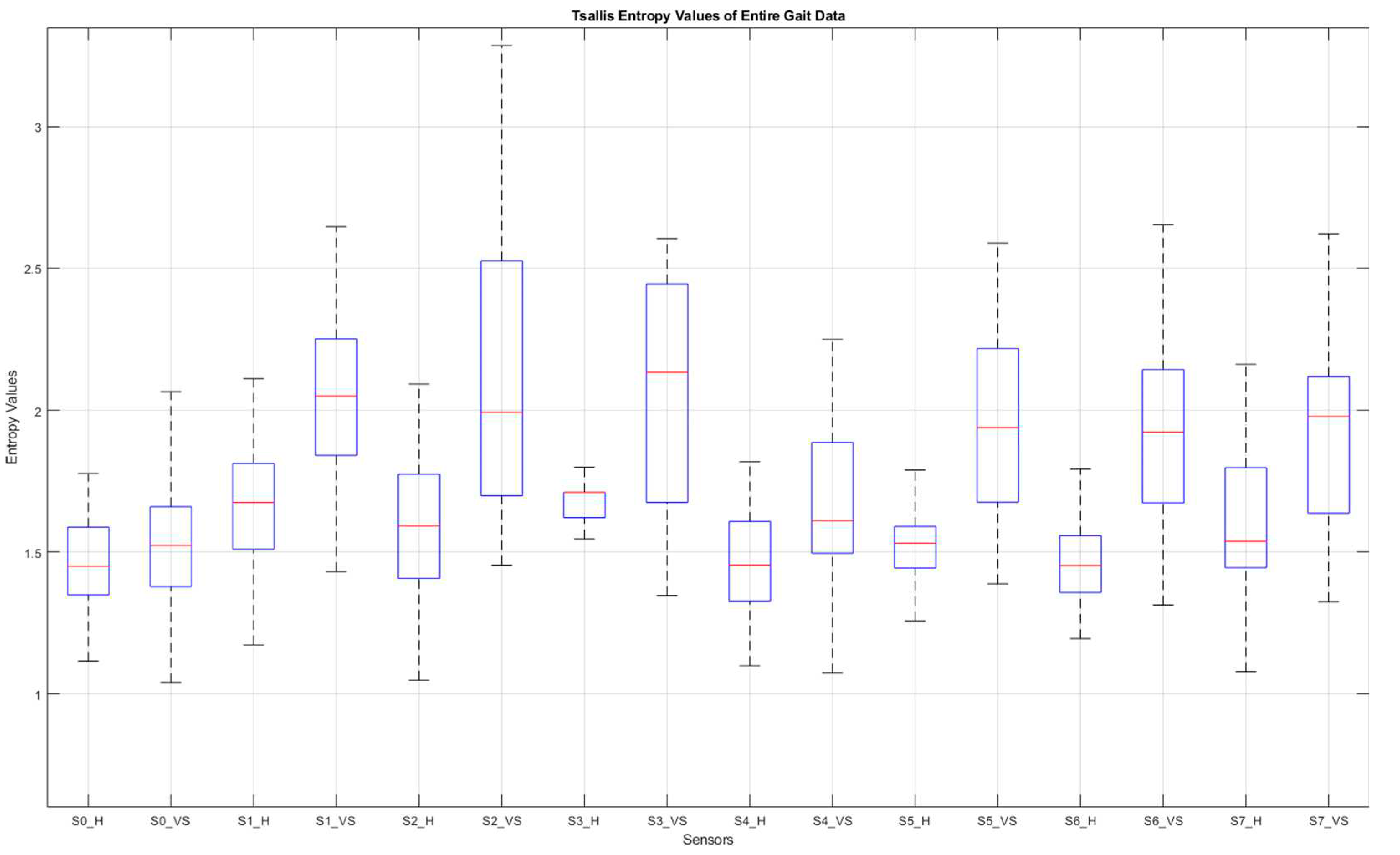

Figure 10 summarizes the entire-gait TE-values for all participants.

Figure 9.

(a) and (c) Detrended data with absolute value taken from figures 8b and 8d and (b) and (d) the histograms produced from these graphs.

Figure 9.

(a) and (c) Detrended data with absolute value taken from figures 8b and 8d and (b) and (d) the histograms produced from these graphs.

Table 5.

TE values calculated from each sensor data of sample subjects.

Table 5.

TE values calculated from each sensor data of sample subjects.

| |

Healthy Subject (no. 22) |

VS Subject (no. 30) |

| Sensor |

Entire Gait |

Stepwise Max |

Entire Gait |

Stepwise Max |

| S0 |

1.39 |

0.98 |

1.29 |

0.80 |

| S1 |

2.15 |

0.83 |

2.10 |

1.02 |

| S2 |

1.38 |

0.72 |

1.58 |

1.03 |

| S3 |

1.24 |

0.63 |

2.36 |

0.99 |

| S4 |

1.08 |

0.87 |

1.61 |

1.08 |

| S5 |

1.38 |

0.79 |

1.96 |

0.67 |

| S6 |

1.36 |

0.82 |

1.64 |

0.17 |

| S7 |

1.54 |

0.86 |

1.98 |

1.56 |

Figure 10.

Box plot of the entire-gait TE-values for all participants. S: sensor, H: healthy, VS: diseased.

Figure 10.

Box plot of the entire-gait TE-values for all participants. S: sensor, H: healthy, VS: diseased.

As described in Data Processing section, thirty-two classifiers provided by the Classification Learner Tool in Matlab were trained using sixteen features with ten-fold cross-validation. The average accuracies of the major classification algorithms are listed in

Table 6.

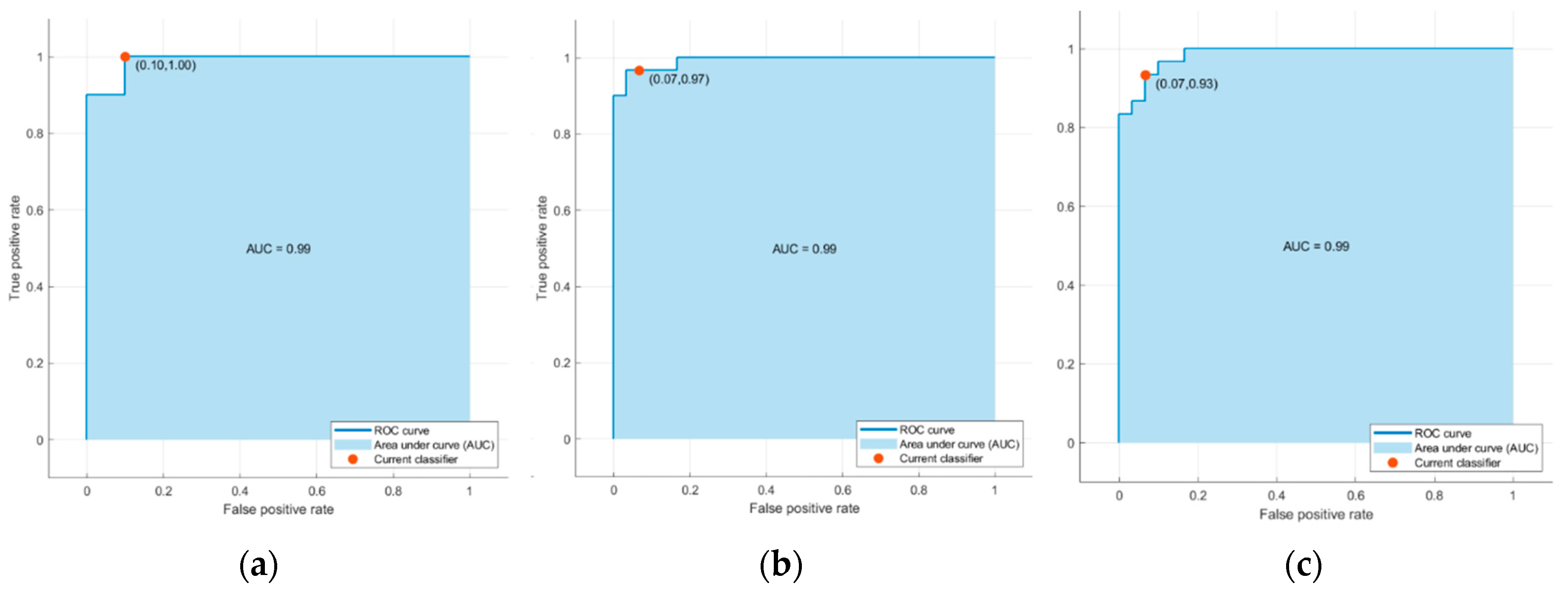

Table 7 and

Figure 11 display the confusion matrices and corresponding Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for one of the ten training-test set pairs of the top three classifiers

Table 6.

Accuracy of Major Classification Algorithms.

Table 6.

Accuracy of Major Classification Algorithms.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy (%) |

| SVM (Gaussian) |

95.0 |

| Logistic Regression |

95.0 |

| KNN (Cosine) |

93.3 |

| Neural Network (Wide) |

93.3 |

| Kernel (SVM) |

91.7 |

| Ensemble (Bagged Tree) |

88.3 |

| Naïve Bayes (Kernel) |

86.7 |

| Quadratic Discriminant |

78.3 |

| Decision Tree (Fine) |

73.3 |

Table 7.

Confusion Matrices for One of the Ten Training-Test Set Pairs.

Table 7.

Confusion Matrices for One of the Ten Training-Test Set Pairs.

| Predicted Class |

SVM (Gaussian) |

Logistic Regression |

KNN (Cosine) |

| H |

D |

H |

D |

H |

D |

| H |

30 |

0 |

29 |

1 |

28 |

2 |

| D |

3 |

27 |

2 |

27 |

2 |

28 |

Figure 11.

ROC curves associated with (

a) the support vector machine (SVM) model with Gaussian kernel, (

b) Logistic Regression (

c) k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm using cosine similarity in

Table 6.

Figure 11.

ROC curves associated with (

a) the support vector machine (SVM) model with Gaussian kernel, (

b) Logistic Regression (

c) k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm using cosine similarity in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

This study is carried out in conjunction with a project where our ultimate goal is to identify the specific diseases of individuals suffering from VS dysfunction, along with the level of the problem. In the whole of the project a machine learning process will be conducted using distinctive features as input. In this context, features that will be effective in defining the problem will be searched and all of them will be placed in the candidate features basket, that is, they will be selected to take part in the feature reduction stage. According to the experience of the audiologists with whom we conducted the experiments, some important points should be considered when collecting data from patients in order to achieve a high level of accuracy in diagnosis. These are particularly highlighted as obtaining data in a short time and under stress-free conditions. Taking these instructions into account and thus aiming to capture features from a short walk, we performed multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MFDFA) in our previous study [

17]. Our current study also uses the same data as in our previous work to provide additional features for the feature selection/reduction step.

In this study we utilized TE-based methods for feature extraction from gait data collected from insole pressure/force sensors. The reason for considering the TE was its capability to capture the level of the fluctuations in the detrended data, providing insight into the complexity and irregularity of the gait pattern. Unlike other entropies, TE enables a parameterized analysis, offering flexibility in quantifying uncertainty and capturing certain characteristics of the data distribution.

Data from eight insoles sensors, four under each foot, were first normalized and then detrended to provide information about fluctuation around the trend curve of the individual. With this process we aimed to consider the gait habit of the person in order not to misinterpret an unusual gait habit as a definition of balance disorder. As one of the effective innovations brought by this study, we developed an algorithm that determines the trend curve at each step. The efficiency of this algorithm shows itself when the results are compared with other curve fitting methods. Using our algorithm, we achieved an average accuracy of 95% in distinguishing VS patients from healthy, while the best rate was 86.7% even with a fourth-order curve-fitting polynomial. A total of sixteen features were involved in the classification process, eight of which were derived from the TEs of the entire gait cycle and the other eight from the step-by-step TE change for each sensor. The TE value for the entire gait cycle and the step-by-step variation of the TE value are observed to be greater in VS patients than in healthy individuals, which we explain by the high data deviation around the trend curve for these individuals. The TE parameter q was determined experimentally as 0.82. As we can see from

Figure 10, of all the sensor data, those from under-the-heel sensors (S0 and S4) contributed the least to the classification process, such that the differences in TE values for these data were the smallest. This picture is easy to understand, as the sensors in question are placed at points where even a diseased person does not show a significant fluctuation.

As data collection time, the subjects had to walk for around 10-15 seconds. As we explained in detail in [

17], this time interval is much shorter than most experiments in studies in the literature. With such a short test time, high accuracy is achieved by processing the instantaneous values of the gait data using appropriate methods rather than dealing with step-based features such as stride time, stance time, etc.

SVM with Gaussian kernel and logistic regression performed best in the classification process with 95%, followed by KNN (cosine) and neural network (wide) with 93.3%. At this point, we would like to emphasize that we defined our criterion for categorizing any feature as distinctive and labeling it as a candidate for feature reduction as an individual accuracy level threshold of 90%. [

17]; thus, the TE based features pass this evaluation stage successfully. On the other hand, we believe that a more reliable result will be achieved with the increase in the number of participants.

In addition to numerical values presented in the Results section, we provide further statistical data in

Table 8, in order to have a more meaningful idea about the results.

For now, we are experimenting for the binary classification phase of the entire project so that the individual can be described as ‘suffering’ or ‘healthy’. As we stated in [

17], features that take into account one’s own trend are expected to be quite effective in determining the stage of the problem. So, we look forward to using these features also for this future step of the whole project.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.İ.; methodology, S.İ.; software, H.Y.K.; validation, H.Y.K.; Data acquisition, S.İ.; formal analysis, S.İ.; investigation, H.Y.K.; data curation, H.Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, S.İ.; visualization, H.Y.K.; supervision, S.İ.; project administration, S.İ.; funding acquisition, S.İ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research constitutes a significant component of a project entitled "Development of an Algorithm for Dynamic Vestibular System Analysis and Design of a Balance Detector," which received funding from the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) for the conduction of experiments (Project no: 115E258).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The experiments were carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Istanbul University, as evidenced by the granted approval number A-57/07.07.2015.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian to participate in experiments before starting the process.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Professor Ahmet Ataş and Assistant Professor Eyyup Kara from the Audiology Department of Cerrahpaşa Medical School-Istanbul for their invaluable encouragement in initiating this research project and their unwavering support in data collection. Additionally, the authors extend their deep appreciation to Tunay Çakar and Saddam Heydarov for their assistance during the sensor calibration process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Khan, S.; Chang, R. Anatomy of the vestibular system: A review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013, 32, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanicek, N.; King, S.A.; Gohil, R.; et al. Computerized dynamic posturography for postural control assessment in patients with intermittent claudication. JoVE. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, N.; Horak, F.B.; Hausdorff, J.M. Classification of gait disturbances: Distinguishing between continuous and episodic changes. Mov Disord. 2013, 28, 1469–1473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bovonsunthonchai, S.; Vachalathiti, R.; Hiengkaew, V.; et al. Quantitative gait analysis in mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and cognitively intact individuals: A cross-sectional case–control study. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22, 767. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Detection and assessment of Parkinson’s disease based on gait analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.R.; Reschke, M.F. Aging, vestibular function, and balance control: Physiological and behavioral considerations. Current Opinion in Physiology 2021, 19, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ikizoglu, S.; Heydarov, S. Accuracy comparison of dimensionality reduction techniques to determine significant features from IMU sensor-based data to diagnose vestibular system disorders. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, D.K.; Usaha, W.; Pojprapai, S.; Wattanapan, P. Fall Risk Prediction Using Wireless Sensor Insoles with Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 23119–23126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidheiny, A.; Swanenburg, J.; et al. Discriminant validity and test re-test reproducibility of a gait assessment in patients with vestibular dysfunction. BMC ear, nose, and throat disorders 2015, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tsallis, C. Introduction to Nonextensive Statistical Mechanics: Approaching a Complex World. Contemporary Physics 2009, 50/4, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Jia, X.; Ding, H.; Ye, D.; Thakor, N.V. Application of Tsallis entropy to EEG: Quantifying the presence of burst suppression after asphyxial cardiac arrest in rats. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 867–874. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Bezerianos, A.; Paul, J.; Zhu, Y.; Thakor, N. Nonextensive entropy measure of EEG following brain injury from cardiac arrest. Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2002, 305, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Ghosh, D.; Chatterjee, S. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of human gait diseases. Frontiers in Physiology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinyomark, A.; Larracy, R.; Scheme, E. Fractal analysis of human gait variability via stride interval time series. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff, J.M.; Ashkenazy, Y.; Peng, C.; et al. When human walking becomes random walking: Fractal analysis and modeling of gait rhythm fluctuations. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 2001, 302, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Diosdado, A. Fractal and multifractal analysis of human gait. AIP Conference Proceedings 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Günaydın, B.; İkizoğlu, S. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of insole pressure sensor data to diagnose vestibular system disorders. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Higuma, M.; Sanjo, N.; Mitoma, H.; et al. Wholeday gait monitoring in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A relationship between attention and gait cycle. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2017, 1-1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Hidalgo, M.; Ferrández-Pastor, F.J.; Valdivieso-Sarabia, R.J.; et al. Gait analysis using computer vision based on cloud platform and mobile device. Mobile Inf. Syst. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenhu, L.; Yinghua, W.; Xue, S.; et al. Entropy Measures in Anesthesia. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2015, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, W.; Faes, L.; Ivanov, P.C. Entropy measures, entropy estimators, and their performance in quantifying complex dynamics: Effects of artifacts, nonstationarity, and long-range correlations. Phys. Rev. E. 2017, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Pengjian, S. Multiscale Tsallis permutation entropy analysis for complex physiological time series. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2019, 529, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalotti, L.D.G.; Ramírez-Rojas, A.; Vargas, C.A. Tsallis q-Statistics in Seismology. Entropy 2023, 25, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilk, G.; Włodarczyk, Z. Some Non-Obvious Consequences of Non-Extensiveness of Entropy. Entropy 2023, 25, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, A.; Burgess-Walker, P.; Naemi, R.; Chockalingam, N. Repeatability of WalkinSense® in shoe pressure measurement system: A preliminary study. The Foot. 2012, 22, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleczek, T.; Ruegg, A.; Harms, H.; Tro, G. Textile pressure sensors for sports applications. 2010 IEEE Sensors 2010, 732–737. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, M.; Nakajima, K.; Takano, C.; et al. An in -shoe device to measure plantar pressure during daily human activity. Medical Engineering & Physics 2011, 33, 638–645. [Google Scholar]

- Salpavaara, T.; Verho, J.; Lekkala, J.; Halttunen, J. Wireless insole sensor system for plantar force measurements during sport events. In Proceedings of the IMEKO XIX World Congress on Fundamental and Applied Metrology, Lisbon, Portugal; 2009; pp. 2118–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, L.; Hua, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Feng, D.D.; Tao, X. In-shoe plantar pressure measurement and analysis system based on fabric pressure sensing array. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 2010, 14, 767–775. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, A.M.; Chowdhury, M.E.; Khandakar, A.; et al. A Systematic Approach to the Design and Characterization of a Smart Insole for Detecting Vertical Ground Reaction Force (vGRF) in Gait Analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSR Technical paper. Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3899023/Interlinkelectronics%20November2017/Docs/Datasheet_FSR.pdf.

- Burden, R.L.; Faires, J.D. Numerical Analysis. In Cengage Learning; Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 144–172. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, L. K-nearest neighbor. Scholarpedia 2009, 4, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Vetter, T.R. Logistic Regression in Medical Research. Anesth Analg. 2021, 132, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geron, A. Chapter 5: Support Vector Machines. In Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems. O’Reilly Media, Incorporated. 2019.

- Lin, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, T.; Jeng, S.; Chen, J. Support vector machine for EEG signal classification during listening to emotional music. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE 10th Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing; 2008; pp. 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Saccà, V.; Campolo, M.; Mirarchi, D.; et al. On the Classification of EEG Signal by Using an SVM Based Algorithm. 2018; 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, I.; Singh, D.; Khosla, A. QRS detection using K-Nearest Neighbor algorithm (KNN) and evaluation on standard ECG databases. Journal of Advanced Research 2013, 4, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yean, C.W.; Khairunizam, W.; Omar, M.I.; et al. Analysis of the distance metrics of KNN classifier for EEG signal in stroke patients. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computational Approach in Smart Systems Design and Applications (ICASSDA); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erguzel, T.T.; Noyan, C.O.; Eryilmaz, G.; et al. Binomial Logistic Regression and Artificial Neural Network Methods to Classify Opioid-Dependent Subjects and Control Group Using Quantitative EEG Power Measures. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience 2019, 50, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maria, G.; Juan, S.; Helbert, E. EEG signal analysis using classification techniques: Logistic regression, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, and convolutional neural networks. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).