Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

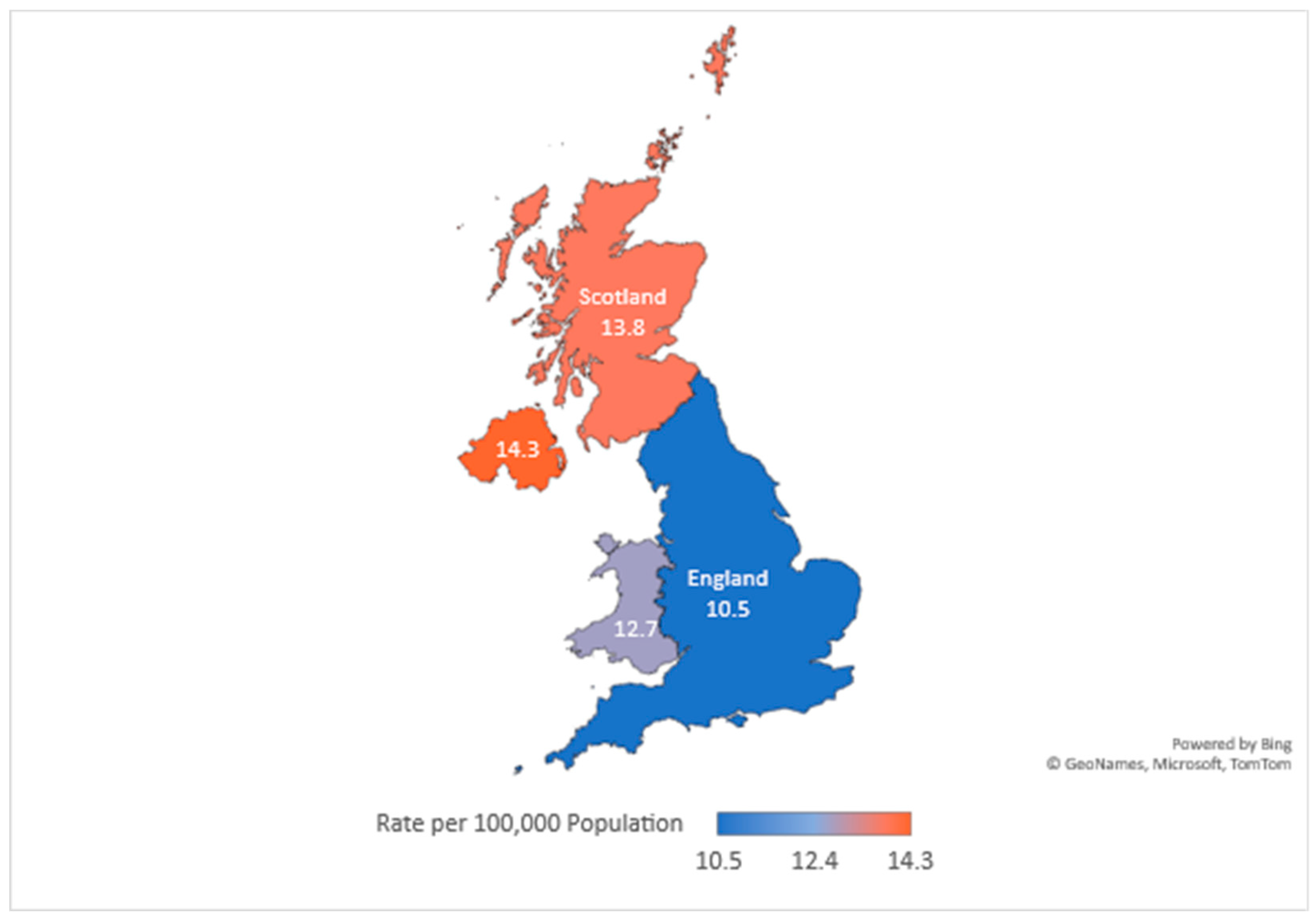

2. Epidemiology of Suicide in the UK

3. Risk Factors for Suicide

4. Screening and Assessment Tools

- The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C SSRS)

- SuicideIdeation Questionnaire (SIQ)

- Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (B SSI)

- ManchesterSelf-Harm Rule (MSHR)

- EcologicalMomentary Assessment (EMA)

- Other assessment tools

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alves, V.M.; Francisco, L.C.; Melo, A.R.D.; Novaes, C.R.; Belo, F.M.; Nardi, A.E. Trends in suicide attempts at an emergency department. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 2017, 39, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, A.; Ross, E.; Reilly, D. Parental mental health and risk of poor mental health and death by suicide in offspring: A population-wide data-linkage study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K.K., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Pillai, J.S.S.K.; Gill, K.O. K.K.; Pillai, J.S.S.K.; Gill, K.O.; & Hui.; Swami., 2010.

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B.H. Suicide and suicide risk. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health, W. ; O., 2014.

- Zakowicz, P.; Skibin´ska, M.; Wasicka-Przewoz´na, K.; Skulimowski, B.; Was´niewski, F.; Chorzepa, A.; Róz˙an´ski, M.; Twarowska- Hauser, J.; Pawlak, J. Impulsivity as a Risk Factor for Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Kim, C.; Turecki, G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolote, J.M.; Fleischmann, A. Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: A worldwide perspective. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 181–181. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, C.D.; Loncar, D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, T.; Rich, J.; Davies, K.; Lewin, T.; Kelly, B. The challenges of predicting suicidal thoughts and behaviours in a sample of rural Australians with depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 928–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, S.; Wetherall, K.; Clark, A.; Ryan, C.; Kirtley, O.J.; Smith, M.; Connor, R.C. Adverse childhood experiences and hospital-treated self-harm. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 1235–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calati, R.; Ferrari, C.; Brittner, M.; Oasi, O.; Olié, E.; Carvalho, A.F.; Courtet, P. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 245, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E. , 2005.

- Orden, K.A.V.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review 2010, 117, 575–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, R.J.; Cullen, B.; Graham, N.; Lyall, D.M.; Mackay, D.; Okolie, C.; Pearsall, R.; Ward, J.; John, A.; Smith, D.J. Living alone, loneliness and lack of emotional support as predictors of suicide and self-harm: A nine-year follow up of the UK Biobank cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 279, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Näher, A.F.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Hegerl, U. Associations of Suicide Rates With Socioeconomic Status and Social Isolation: Findings From Longitudinal Register and Census Data. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, C.P. Conditions predisposing to suicide: A review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1977, 164, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, N.S.; Mahler, J.C.; Gold, M.S. Suicide risk associated with drug and alcohol dependence. Journal of Addictive Diseases 1991, 10, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuodelis-Flores, C.; Ries, R.K. Addiction and suicide: A review. The American Journal on Addictions 2015, 24, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarin, R.M.; Fioritti, A. Mortality trends among cocaine users treated between 1989 and 2013 in northern Italy: Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2018, 50, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Keyes, K.; Ogburn, E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases. Addiction 2006, 101, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasato, K. Nihon Rinsho 2010, 68, 1431–1436. 68.

- Oyefeso, A.; Ghodse, H.; Clancy, C.; Corkefy, J.M. Suicide among drug addicts in the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1999, 175, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Kalk, N.J.; Andrews, R.; Yates, S.; Nahar, L.; Kelleher, M.; Paterson, S. Alcohol and cocaine use prior to suspected suicide: Insights from toxicology. Drug and Alcohol Review 2021, 40, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haw, C.; Hawton, K.; Niedzwiedz, C.; Platt, S. , 2013.

- Bond, K.S.; Cottrill, F.A.; Mackinnon, A.; Morgan, A.J.; Kelly, C.M.; Armstrong, G.; Kitchener, B.A.; Reavley, N.J.; Jorm, A.F. Effects of the Mental Health First Aid for the suicidal person course on beliefs about suicide, stigmatising attitudes, confidence to help, and intended and actual helping actions: An evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameshwaraiah, S.T.; Manohar, S.; Thiagarajan, K. SUICIDE ATTEMPTS AND RELATED RISK FACTORS IN PATIENTS ADMITTED TO TERTIARY CARE CENTRE IN SOUTH INDIA. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2018, 7, 2916–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizabadi, Z.; Aminisani, N.; Emamian, M.H. Socioeconomic inequality in depression and anxiety and its determinants in Iranian older adults. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, K.; Brent, D.; Lucas, C.; Gould, M.; Stanley, B.; Brown, G.; Fisher, P.; Zelazny, J.; Burke, A.; Oquendo, M. Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS); Vol. 10, 2008.

- Duijn, E.V.; Vrijmoeth, E.M.; Giltay, E.J.; Landwehrmeyer, G.B. Suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior according to the C-SSRS in a European cohort of Huntington’s disease gene expansion carriers. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018, 228, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.C.; Carter, T.; Walker, G.; Coad, J.; Aubeeluck, A. Assessing risk of self-harm in acute paediatric settings: A multicentre exploratory evaluation of the CYP-MH SAPhE instrument. BMJ Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, Å.U.; Waern, M.; Beckman, K.; Renberg, E.S.; Dahlin, M.; Runeson, B. Short term risk of non-fatal and fatal suicidal behaviours: The predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale in a Swedish adult psychiatric population with a recent episode of self-harm. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, M.A.G.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. , 2011.

- Giddens, J.M.; Sheehan, K.H.; Sheehan, D.V. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Has the ‘Gold Standard’ Become a Liability? Innov Clin Neurosci 2014, 11, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, W.M. Suicidal ideation questionnaire (SIQ). Psychological Assessment Resources 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mccauley, E.; Berk, M.S.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M.; Cohen, J.; Korslund, K.; Avina, C.; Hughes, J.; Harned, M.; Gallop, R.; et al. , 2018.

- Zhang, J.; Brown, G.K. Psychometric properties of the scale for suicide ideation in China. Archives of Suicide Research 2007, 11, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Assessment of Suicidal Intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1979, 47, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.; Kapur, N.; Dunning, J.; Guthrie, E.; Appleby, L.; Mackway-Jones, K. A Clinical Tool for Assessing Risk After Self-Harm. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2006, 48, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, B.L.; Han, J.; Benassi, H.; Batterham, P.J. , 2020.

- Kivelä, L.; Does, W.A.J.V.D.; Riese, H.; Antypa, N. , 2022.

- Sedano-Capdevila, A.; Porras-Segovia, A.; Bello, H.J.; Baca-García, E.; Barrigon, M.L.; Barrigon, M.L. SECTION EDITOR) Use of Ecological Momentary Assessment to Study Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior: A Systematic Review; 2021.

- Cull, J.G.; Gill, W.S. Suicide probability scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Go, H.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.P. A validation study of the suicide probability scale for adolescents (SPS-A). Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 2000, 680–690. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Weissman, A.; Lester, D.; Trexler, L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1974, 42, 861–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, E.H.; Hwang, S.T.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.H. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 2015, 54, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, P.M.; Osman, A.; Barrios, F.X.; Kopper, B.A.; Baker, M.T.; Haraburda, C.M. Development of the reasons for living inventory for young adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2002, 58, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M.M.; Goodstein, J.L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Chiles, J.A. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: The reasons for living inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1983, 51, 276–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Kopper, B.A.; Barrios, F.X.; Osman, J.R.; Besett, T.; Linehan, M.M. The brief reasons for living inventory for adolescents (BRFL-A). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 1996, 24, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westefeld, J.S.; Cardin, D.; Deaton, W.L. Development of the college student reasons for living inventory. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 1992, 22, 442–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kang, E.; Jeong, J.W.; Paik, J.W. Korean suicide risk screening tool and its validity. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2013, 13, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; You, S. Development and validation of the suicidal imagery questionnaire. Kor J Clin Psychol 2020, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, E.K.; Song, J.J.; Park, H.S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Lee, M.S. Development of the suicide risk scale for medical inpatients. Journal of Korean Medical Science 2018, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, I.C.; Jo, S.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, G.R.; Lee, D.H.; Jeon, H.J. A review of suicide risk assessment tools and their measured psychometric properties in Korea. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 679779–679779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Shaghaghi, A.; Allahverdipour, H. Measurement Scales of Suicidal Ideation and Attitudes: A Systematic Review Article. Health Promot Perspect 2015, 5, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowosegbe, A.; Oyelade, T. Application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Detecting and Preventing Suicide Ideation: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, C.; Seyedsalehi, A.; Vardavoulia, K.; Bittar, A.; Velupillai, S.; Shetty, H.; Schmidt, U.; Dutta, R. Using natural language processing to extract self-harm and suicidality data from a clinical sample of patients with eating disorders: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mens, K.V.; Elzinga, E.; Nielen, M.; Lokkerbol, J.; Poortvliet, R.; Donker, G.; Heins, M.; Korevaar, J.; Dückers, M.; Aussems, C.; et al. Applying machine learning on health record data from general practitioners to predict suicidality. Internet Interventions 2020, 21, 100337–100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’dea, B.; Larsen, M.E.; Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Christensen, H. , 2017.

- Larsen, M.E.; Nicholas, J.; Christensen, H. A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuij, C.; Ballegooijen, W.V.; Ruwaard, J.; Beurs, D.D.; Mokkenstorm, J.; Duijn, E.V.; Winter, R.F.P.D.; Connor, R.C.; Smit, J.H.; Riper, H.; et al. Smartphone-based safety planning and self-monitoring for suicidal patients: Rationale and study protocol of the CASPAR (Continuous Assessment for Suicide Prevention And Research) study. Internet Interventions 2018, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinengo, L.; Galen, L.V.; Lum, E.; Kowalski, M.; Subramaniam, M.; Car, J. Suicide prevention and depression apps’ suicide risk assessment and management: A systematic assessment of adherence to clinical guidelines. BMC Medicine 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torok, M.; Han, J.; Baker, S.; Werner-Seidler, A.; Wong, I.; Larsen, M.E.; Christensen, H. , 2020.

- Pham, K.T.; Nabizadeh, A.; Selek, S. Artificial Intelligence and Chatbots in Psychiatry. Psychiatric Quarterly 2022, 93, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torous, J.; Bucci, S.; Bell, I.H.; Kessing, L.V.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M.; Whelan, P.; Carvalho, A.F.; Keshavan, M.; Linardon, J.; Firth, J. The growing field of digital psychiatry: Current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 318–335. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A.P.C.; Trappey, C.V.; Luan, C.C.; Trappey, A.J.C.; Tu, K.L.K. A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a. Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 9071–9071. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Sánchez, G.; Camargo-Henríquez, I.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.L.; Franco-Martín, M.; Torre-Díez, I.D.L. Suicide Prevention Mobile Apps: Descriptive Analysis of Apps from the Most Popular Virtual Stores. JMIR MHealth and UHealth 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).