Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Prevalence of DV in Australia

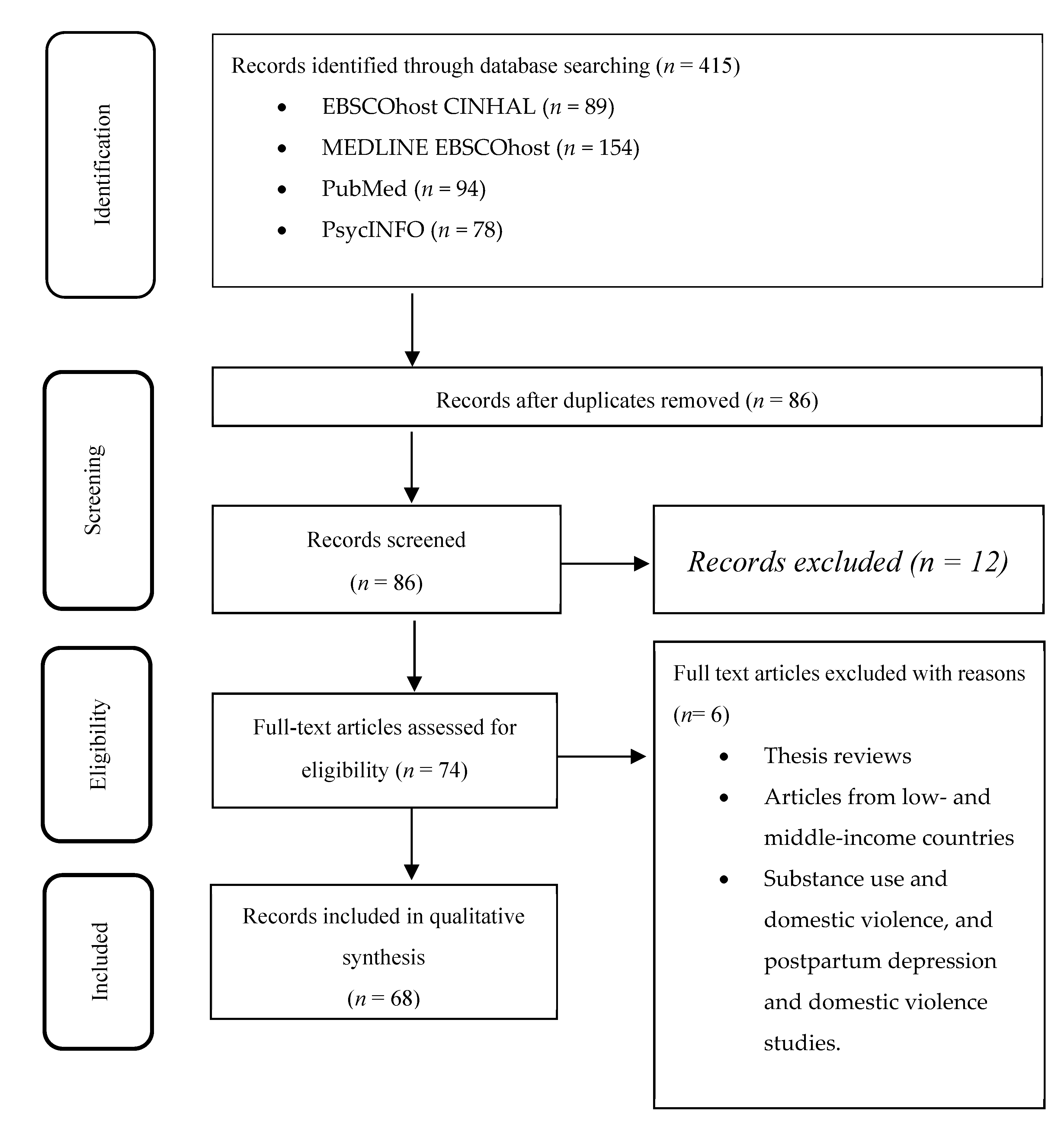

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping Review Research Question

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Why DV Victims Do Not Disclose to GPs and Other Primary Health Professionals

3.2. What Symptoms and Comorbidities do Patients Present to Healthcare Providers?

3.3. Detection and Intervention in the Clinical Setting

3.4. What is Needed to Generate more Effective Responses to DV in Primary Healthcare Settings?

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Committee of the Red Cross. Addressing Sexual Violence; 2020. https://www.icrc.org/en/what-we-do/sexual-violence.

- United Nations. What is Domestic Abuse? 2020. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse.

- Rees, S.; Silove, D.; Chey, T.; Ivancic, L.; Steel, Z.; Creamer, M.; Teeson, M.; Bryant, R.; McFarlane, A.C.; Mills, K.L.; Slade, T.; Carragher, N.; O’Donnell, M.; Forbes, D. Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. American Medical Association 2011, 306, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carton, H.; Egan, V. The dark triad and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 105, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.A. Intimate partner violence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2015, 187, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendt, S. Domestic violence in rural Australia. Federation Press, 2009.

- Hegarty, K.; O'Doherty, L.; Taft, A.; Chondros, P.; Brown, S.; Valpied, J.; Astbury, J.; Taket, A.; Gold, L.; Feder, G.; Gunn, J. Screening and counseling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): A cluster randomized trial. The Lancet 2013, 382, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Taking stock of the global partnership for development; 2015. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG_Gap_2015_E_web.pdf.

- Soh, H.J.; Grigg, J.; Gurvich, C.; Gavrilidis, E.; Kulkarni, J. Family violence: An insight into perspectives and practices of Australian health practitioners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2018. http://10.1177/0886260518760609.

- World Health Organisation. Violence against women; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Watts, C. Violence against women: An urgent public health priority. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2011, 89, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, K.L.; O’Doherty, L.J.; Chondros, P.; Valpied, J.; Taft, A.J.; Astbury, J.; Gunn, J.M. Effect of type and severity of intimate partner violence on women’s health and service use: Findings from a primary care trial of women afraid of their partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2013, 28, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalacha, L.A.; Hughes, T.L.; McNair, R.; Loxton, D. Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: Findings from the Australian longitudinal women’s health study. BMC Women’s Health 2017, 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0452-5 Show / Hide Editor. [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, S. Intimate partner violence: Australian nurses and midwives trained to provide care? The Australian Nursing Journal 2013, 20, 37–37. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Effects of Violence against women; 2019. https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety/effects-violence-against-women.

- Taket, A.; O’Doherty, L.; Valpied, J.; Hegarty, K. What do Australian women experiencing intimate partner abuse want from family and friends? Qualitative Health Research 2016, 24, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, G.; Hussain, R.; Kibele, E.; Rahman, S.; Loxton, D. Influence of intimate partner violence on domestic relocation in Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan young Australian Women, Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1597–1620. http://10.1177/1077801216628689.

- Mission Australia. Domestic and Family Violence Statistics; 2020. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/domestic-and-family-violence-statistics.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, domestic and sexual violence; 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/domestic-violence/overview.

- Puccetti, M.; Greville, H.; Robinson, M.; White, D.; Papertalk, L.; Thompson, S.C. Exploring readiness fir change: Knowledge and attitude towards family violence among community members and service providers engaged in primary prevention in regional Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017.

- Meuleners, L.B.; Lee, A.H.; Xia, J.; Fraser, M.; Hendrie, D. Interpersonal violence presentation to general practitioners in Western Australia: Implications for rural and community health. Australian Health Review 2011, 35, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, L.; Versteegh, L.; Lindgren, H.; Taft, A. Differences in help-seeking behaviours and perceived helpfulness of services between abused and non-abused women: A cross-sectional survey of Australian postpartum women. Health & Social Care in the Community 2019, 28, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland, D.; Woolhouse, H.; Mensah, F.K.; Hegarty, K.; Hiscook, H; Brown, S. J. The case for early intervention to reduce the impact of intimate partner abuse on child outcomes: Results of an Australian cohort of first-time mothers. Birth 2014, 41, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Recoded Crime – Victims, Australia; 2019. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/recorded-crime-victims-australia/latest-release.

- McGarry, A. Older women, intimate partner violence and mental health: A consideration of the particular issue for health and healthcare practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2017, 26, 2177–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, A. (2020) Pandemics and violence against women and children. Centre for Global Development, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder, N.E. , van Haalen, D.L., Ekker, K. et al. Professionals’ views on working in the field of domestic violence and abuse during the first wave of COVID-19: a qualitative study in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res, 2021; 21, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, N.; Hooker, L.; Resenhofer, S. Nurse and midwifery education and intimate partner violence: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2017, 26, 2100–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, M.; Rowe, J.; Wallis, M. Normalizing policies of inaction – The case of health care in Australia for women affected by domestic violence. Health care for Women International 2011, 32, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.; Powell, A. "What's the problem?" Australian public policy constructions of domestic and family violence. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, A.J.; Hooker, L.; Humphreys, C.; Hegarty, K.; Walter, R.; Adams, C. Maternal and child health nurse screening and care for mothers experiencing domestic violence (MOVE): A cluster randomized control trial. BMC Medicine 2015, 13, 150–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, M.C.; Taft, A.; Pereira, P.P.G. Intimate partner violence against women and healthcare in Australia: Charting the scene. Ciencia & Saude Coletivia 2012, 17, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno et al. (2015).

- O’Doherty, L.; Taket, A.; Valpied, J.; Hegarty, K. Receiving care for intimate partner violence in primary care: Barriers and enablers for women participating in the weave randomized controlled trial. Social Science & Medicine 2016, 160, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, L. The GP’s role in assisting family violence victims; 2019. https://www.ausdoc.com.au/therapy-update/gps-role-assisting-family-violence-victims.

- Spangaro, J.M.; Zwi, A.B.; Poulos, R.G.; Man, W.Y.N. Who tells and what happens: Disclosure and health service responses to screening for intimate partner violence. Health and Social Care in the Community 2010, 18, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertin et al. 2015.

- Hegarty, K.L.; Gunn, J.M.; O’Doherty, L.J.; Taft, A.; Chondros, P.; Feder, G.; Astbury, J.; Brown, S. Women’s evaluation of abuse and violence care in general practice: A cluster randomized controlled trial (weave). BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, L.; Loxton, D.; James, C. The culture of pretence: A hidden barrier to recognizing, disclosing and ending domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2016, 26, 220–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, K.L.; O’Doherty, L.J.; Astbury, J.; Gunn, J. Identifying intimate partner violence when screening for health and lifestyle issues among women attending general practice. Australian Journal of Primary Health 2012, 18, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, KL; Bush, R. Prevalence and associations of partner abuse in women attending general practice: a cross-sectional survey, Aust NZJ Public Health 2002, 26, 437–424. 2002, 26, 437–424. [CrossRef]

- Mertin, P.; Moyle, S.; Veremeenko, K. Intimate partner violence and women's presentation in general practice settings: Barriers to disclosure and implications for therapeutic interventions. Clinical Psychologists 2014, 19, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astbury, J.; Bruck, D.; Loxton, D. Forced sex: A critical factor in the sleep difficulties of young Australian women. Violence and Victims 2011, 26, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, D.; Astbury, J. Population study on the predictors of sleeping difficulties in young Australian women. Behavioural Sleep Medicine 2012, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertin, P.; Mohr, P.B. Incidence and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorders in Australian victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence 2000, 15, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, M.T.; Ford-Gilboe, M.; Regan, S. Primary health care service use among women who have recently left an abusive partner: Income and racialization, unmet need, fits of services, and health. Health Care for Women International 2015, 36, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Kylee, T.; Woodall, A.; Morgan, C.; Feder, G.; Howard, L. Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: A qualitative study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2011, 198, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharman, L.S.; Douglas, H.; Price, E.; Sheeran, N.; Dingle, G. 2018. Associations between unintended pregnancy, domestic violence and sexual assault in a population of Queensland women. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 2011, 26, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taft, A.; Watson, L. Depression and termination of pregnancy (induced abortion) in a national cohort of young Australian women: The confounding effect of women's experience of violence. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 75–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-de-las-Heras, S.; Velasco, C.; Luna, J.; Martin, A. Unintended pregnancy and intimate partner violence around pregnancy in a population-based study. Journal of the Australian College of Midwives 2015, 28, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, R.N. Domestic violence: Can doctors do more to help? The Medical Journal of Australia 2012, 197, 75–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Health. 2019.

- Department of Health. 2018.

- Taft, A.J.; Small, R.; Humphreys, C.; Hegarty, K.; Walter, R.; Adams, C.; Agis, P. Enhanced maternal and child health nurse care for women experiencing intimate partner/family violence: Protocol for MOVE, a cluster randomized trial of screening and referral in primary health care. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 811–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin et al. 2009.

- O'Doherty, L.; Hegarty, K.; Ramsey, J.; Davidson, L.; Feder, G.; Taft, A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Library 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Screening, risk assessment and safety planning; 2010. https://www.avertfamilyviolence.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2013/06/Screening_Risk_Assessment.pdf.

- MacMillan, H.L.; Wathen, N.; Jamieson, E.; Boyle, M.H.; Shannon, H.S.; Ford-Gilboe, M.; Worster, A.; Lent, B.; Coben, J.H.; Campbell, J.C.; MeNutt, L. Screening for intimate partner violence in healthcare setting: A randomized control trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Routine Screening; 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/routine-screenings.

- The University of Queensland. Domestic Violence Case Studies; 2018. https://law.uq.edu.au/research/dv/using-law-leaving-domestic-violence/case-studies.

- Debra, P. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An Australian case study. Journal of Interpersonal violence 2019, 34, 2333–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, H.; Robbins, R.; Bellamy, C.; Banks, C.; Thackray, D. Adult social work and high-risk domestic violence cases. Journal of Social Work 2018, 18, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangaro, J.M.; Poulos, R.; Zwi, A. Pandora doesn't live here anymore: Normalization of screening for intimate partner violence in Australian antenatal, mental health, and substance abuse services. Violence and Victims 2011, 26, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenman, R.; Tennekoon, V.; Hill, L.G. Measuring bias in self-reporting. International Journal of Behavioural & Healthcare Research 2011, 2, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.E. Gender empowerment in the health aid sector: Locating best practice in the Australian context. Australian Journal of International Affairs 2018, 72, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, R.; Aston, M.; Price, S. Let's talk about sex: A feminist poststructural approach to addressing sexual health in the healthcare setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 28, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.L.; Umberson, D. ; Gendering Violence: Masculinity and power in men's accounts of domestic violence. Gender & Society 2001, 15, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskoff, E.; Parsell, C. Preventing domestic violence by changing Australian gender relations: Issues and considerations. Australian Social Work 2019, 73, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, N. Degendering the problem and gendering the blame: Political discourse on women and violence. Gender & Society 2001, 15, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, M.; Rowe, J.; Wallis, M. Reconceptualising health and health care for women affected by domestic violence. Contemporary Nurse 2012, 42, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, L.; Bernadette, W.; Verrinder, G. Domestic violence screening in maternal and child health nursing practice: A scoping review. Contemporary Nurse 2012, 42, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleak, H.; Hunt, G.; Hardy, F.; Brett, D.; Bell, J. Health staff responses to domestic and family violence: The case for training to build confidence and skills. Australian Social Work 2020, 74, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaria, G.; Beccaria, L.; Dawson, R.; Gorman, D.; Harris, J.A.; Hossain, D. Nursing student’s perception and understanding of intimate partner violence. Nurse Education Today 2013, 33, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. 2003.

- Parkinson, D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An Australian case study. Journal of Interpersonal violence 2017, 34, 2333–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).