1. Introduction

Currently, many countries waste food products (processed, and minimally processed) for different reasons, being the main reason for food with expired dates for human consumption, thus generating scarcity of food and food insecurity. In this regard, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reported that every year the food is wasted in large volumes, exceeding 100 million tons on average. Likewise, it is shown that developed countries are responsible for 56% of the food lost worldwide while developing countries are responsible for 44% [

1]. In general terms, developed countries waste most of their food in the consumption stage, while developing countries suffer these losses in the production and consumption stage [

2,

3].

According to Kavanaugh and Quinlan [

4] and Davenport et al. [

5], consumers decide to discard food for different reasons, such as the excessive purchase of food, food with expiration dates close to expiration, incorrect interpretation of the different types of terms related to expiration dates (e.g., “

expiration date” and “

best before”) found on food packaging or labels [

4,

5]. With respect to the last point, consumers often mistakenly believe that the terms "

expiration date" and "

best before" only convey information about the safety food. Thus, the “

expiration date” refers to microbiology quality and “

best before” term to organoleptic quality.

The confusion of the consumer about the interpretation of the different types of expiration date labels that exist in the world contributes to the generation of food waste, which mostly occurs in homes, this carries a social, economic, and environmental problem, which is increasing as the years go by [

4], Zielińska et al. [

6], and Neff et al. [

7], mentioned that an incorrect interpretation of expiration dates leads to not consuming food; they also pointed out that consumers discard food products when these approach the expiration date [

8,

9]. In addition, Kavanaugh and Quinlan [

4] concluded that these problems that consumers have with interpreting, understanding, and knowing about the different types of expiration date labeling arise due to a lack of education.

Currently, in the market there are various ways of labeling the expiration date of a food product, being the labels "

expiration date" and "

best before" of greater importance, also these labeling generate a lot of confusion to consumers [

10]. The term "

expiration date" refers to the fact that the food product is microbiologically altered after its expiration date, while the term "

best before" refers to the fact that the food product is not microbiologically altered, but its organoleptic quality may be altered depending on storage conditions, once that its expiration date has expired [

11,

12]. For such reasons, a lack of understanding of the

expiration date can pose a threat to health; a lack of understanding of the

best before can lead to food waste [

13,

14].

Thus, it is important to know in detail, the degree of understanding of these terms regarding the expiration date, the behavior towards expired food, and the perception of health risks for consuming expired food, of the different types of consumers (gender, age, economic income, level of education), to help solving food waste problems. Many developing countries, do not have enough food to feed their population, generating problems of food insecurity; in consequence, these needs could be covered with all that amount of food that is wasted, year after year [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Thus, the importance of the investigation is mainly in promoting the differentiation of the terms “expiration date” and “best before”. Therefore, the objectives of this research were: to evaluate the consumer's understanding of the expiration dates indicated on packing; identify consumer behavior toward expired food and know the consumer's perception of the health risks of consuming expired food.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey structure

The survey was designed based on the methodology reported by Ankiel and Samotyja[

13], Madilo et al. [

12] and Kavanaugh and Quinlan[

4], with the adjustments and modifications according to the present investigation. The survey was structured based on 13 questions (Supplementary 1), around the labeling of expiration dates found on the packaging or labels of food products. It was worked with two types of terms: "expiration date" and "best before". It was worked with four similar foods, sensitive to deterioration, and basic for human consumption so that the consumer can easily recognize them and objectively differentiate them by each category. Two foods in the category "expiration date", with the following characteristics: high risk to public health, and sensitivity to microbiological deterioration, such as fresh milk and eggs. Two foods in the category "best before", with the following characteristics: lower risk to public health, and sensitivity to organoleptic changes due to storage conditions, such as UHT milk and mayonnaise (made from eggs). The questionary was divided into three sections: consumer understanding of the terms, consumer behavior regarding expired food products, and consumer perception of health risk for consuming expired food products.

2.2. Sample and size determination

The research was carried out with the population of the sector of Lurigancho-Chosica, Lima - Peru, with the following characteristics: people over 18 years of age, and people who buy food products in authorized commercial centers. For the selection of the sample, the simple random sampling technique was used, so that each individual in the population had the same probability of being selected. The sample size was determined using the equation:

where: n: sample size; N: size of the population (240,814 inhabitants, according to the latest Population and Housing Census of 2017 carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics - INEI); Z (96%): Z critical value at the confidence level 96% (2.06); p: probability that the event occurs (0.7); q: probability that the event does not occur (0.3); e: estimation error (0.04).

The calculated sample size was 555 participants (n=555); therefore, with this number of people it was worked in the investigation.

2.3. Survey management

The survey was administered and organized online through the website

www.encuesta.com. The survey was conducted between the months of May and July 2021, online. The questionary was sent to 555 people with different sociodemographic (gender and age) and socioeconomic conditions (monthly income and level of education). Participants were carefully selected at random, in shopping malls. The shopping malls have control over the expired dates of products. Each participant was asked for her email address. The survey was provided to each participant online via her email address. The range of sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics were gender (men, women), age (18-24, 25-39, 40-55, >55 years old), monthly salary (<

$396,

$396 -

$790,

$791-

$1316,

$1317-

$1842, >

$1842), and level of education (completed high school, university student, bachelor/graduate, master/doctorate), as detailed in

Table 1.

2.4. Statistical analysis

From the data obtained, a Chi-square statistical analysis was carried out to search for significant differences between the different sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables of the participants regarding the understanding of the labeling of expiration dates, the behavior towards expired foods and the perception of health risk by consuming expired food. Significance analysis of the data were performed with values of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, for each parameter. The analyzes were performed using the statistical package IBM SPSS Version 25 (IBM®, SPSS®).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Understanding the terms “expiration date” and “best before”

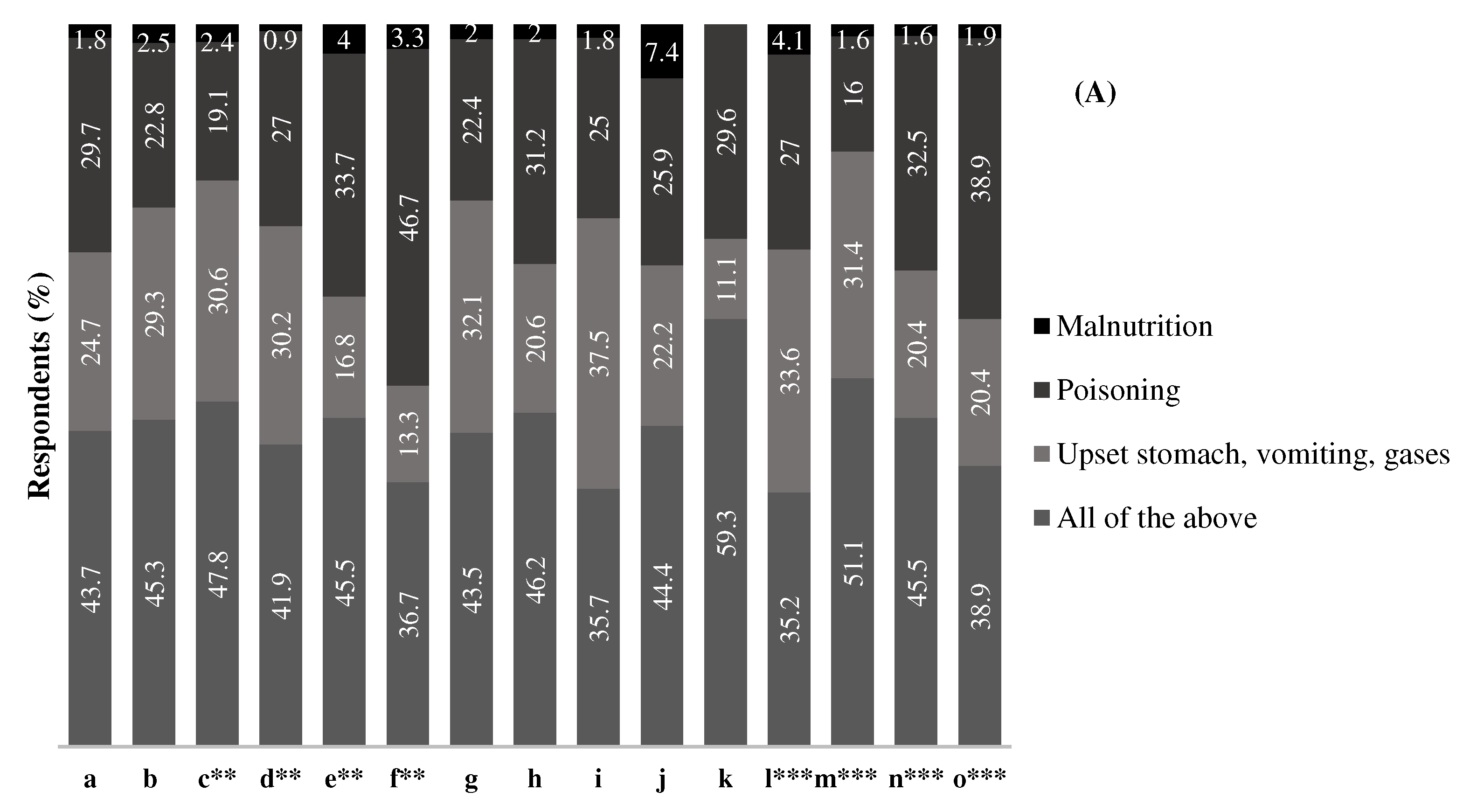

3.1.1. Importance of verifying the terms

The respondents considered it more important to verify the "expiration date" than "best before" when making the purchase of food products (

Table 2); probably, this is due to needing to know when the product will expire. The results obtained in this research agree with Madilo et al. [

12], who noted that 85.9% of the participants rated the expiration date as the most important, followed by the date of manufacture (74.8%), and the health warning (74.2%). Similarly, Zielińska et al. [

6] mentioned that the price and expiration date were more important for consumers when making a purchase decision. Likewise, Azila-Gbettor et al. [

19] and Chan et al. [

20] pointed out that consumers first review the expiration date, then the nutritional information, and finally the instructions for use.

In relation to the people's sociodemographic characteristics: women (90.3%), 40-55 years of age (87.1%), monthly incomes of

$791-

$1316 (82.1%), and master/doctorate (100%), considered it more important to verify the "expiration date"; also, all these sociodemographic characteristics were statistically significant (p<0.05). These results were similar to those found by Zielińska et al. [

6], who mentioned that women and people with higher education check the expiration date more often than men and people with secondary education, respectively.

Of the total number of respondents, 55% do not considered it important to verify "best before" when purchasing food products; likewise, 58.4% of women, 72.8% with monthly income <$396, and 79.8% of university students do not consider it important to verify "best before" and this probably is due to a lack of interest and knowledge about the term. Statistical analysis showed that gender was not statistically significant, while monthly income and level of education were statistically significant (p<0.05).

Hall-Phillips and Shah [

10] reported that people do not consider it important to check for various reasons such as it is not visible, the letter is too small, the date is blurred, and the date imprint is different on each food package. In another way, consumers are confused by the different ways of labeling the expiration dates on the product packaging or label [

9,

21]. Beneke et al. [

22], indicated that consumers buy food products without verifying the expiration dates, due to an excess of confidence in the shopping center. In this sense, the lack of interest in reading food labels during a purchase is a major problem that contributes to environmental pollution and food insecurity.

3.1.2. Interpretation the terms

45% of the total participants mentioned that the terms "expiration date" and "best before" mean the same thing, and 8.5% do not know (

Table 3). Therefore, it can be inferred that the respondents have difficulty differentiating both terms, being this a very serious problem for health, waste food, and food safety. Additionally, Zielińska et al. [

6] found that almost half of their respondents do not clearly interpret the terms of expiration dates, they also pointed out that one in five people have difficulties to answer that type of question. Women (55.2%) had more interpretation criteria about the terms "expiration date" and "best before" than men (37.7%). Similarly, people with a higher level of education (66.7%) interpreted both terms better than people with a lower level of education (23.8%). In addition, the gender and education variables were statistically highly significant (p<0.001).

Whit respect to the definition of the terms, 66.8% of the total of respondents correctly answered the definition of "expiration date". In addition, 78.5% of women, 79.2% of participants with 40-45 years, 92.6% with monthly income of

$1317-

$1842, and 90.7% with a master/doctorate correctly answered the definition of "expiration date." Furthermore, according to the statistical results, gender, age, monthly incomes, and level of education were statistically significant (p<0.01). The results agree with Toma et al. [

8] and Van Boxstael et al. [

23], also these authors mentioned that there is a strong relationship between age and knowledge. However, 47.6% incorrectly answered the definition of "best before", and 7.7% could not define the terms; likewise, in this group were man, younger participants, people with less monthly income, and university students. Therefore, it can be inferred that more than 50% of the respondents have difficulties in defining the meaning of "best before", being a serious problem that could contribute to the generation of food waste. This is probably due to a lack of knowledge of the importance of expiration dates on food products. These results agree with those reported by Zielińska et al. [

6] and Neff et al. [

7], these authors reported that the majority of their respondents erroneously answered this term.

Thus, there is a problem with the interpretation and definition of both terms, as shown by Wilson et al. [

14]; likewise, Hall-Phillips and Shah [

10] concluded that interpreting and defining the meaning of: "expiration date" and "best before", is a major challenge for consumers when buying, and sometimes they make wrong decisions that lead to food waste.

3.1.3. Reading frequency and reasons for not reading the terms

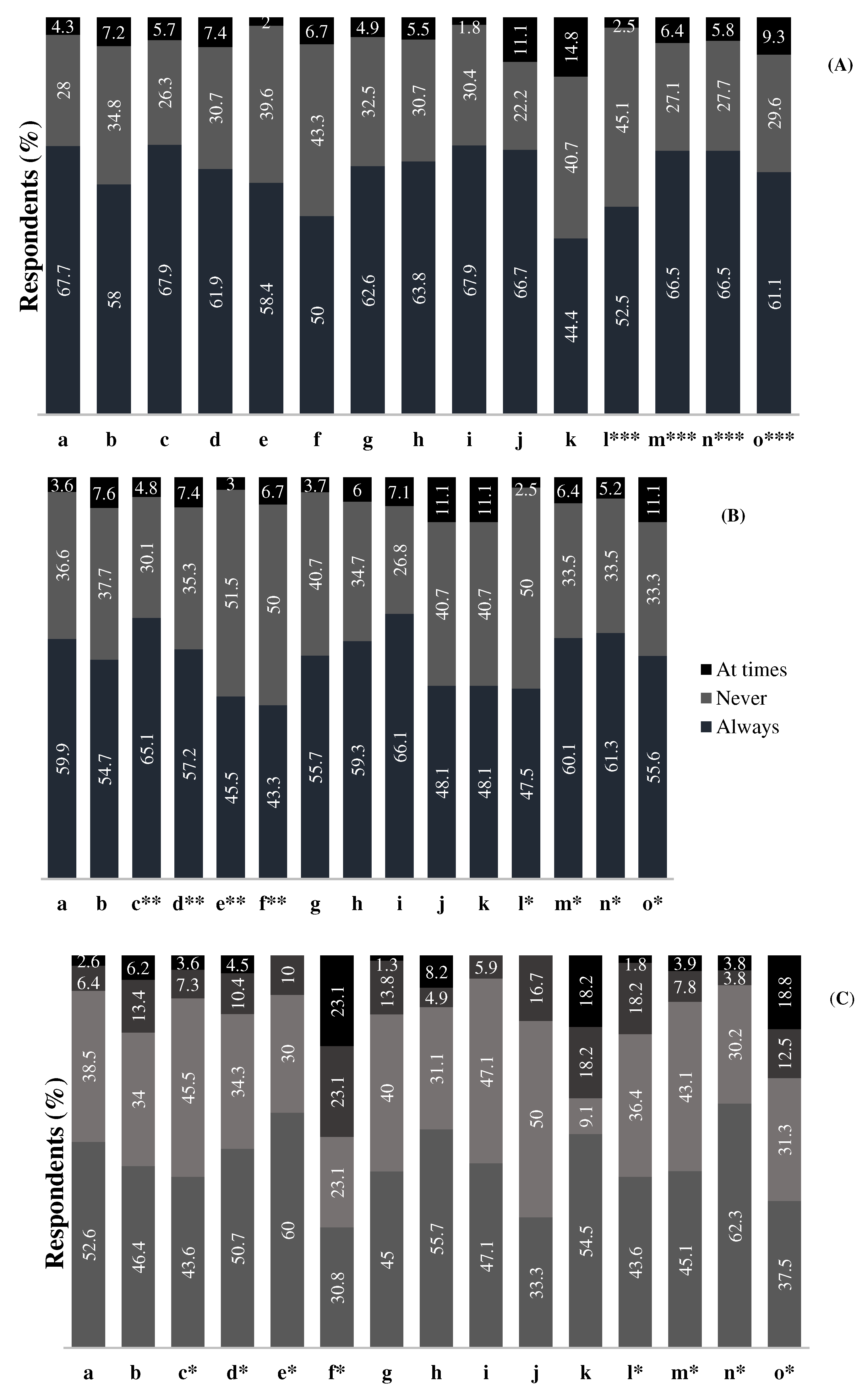

Figure 1A shows that 66.7% of women, 66.5% of university students, and 66.5% of bachelor/graduate, always read the “expiration date”. Similarly, Neff et al. [

7], mentioned that people with a university education show greater interest in reading the "expiration date". Thus, these results are probably related to the time factor, since students could have more time to review the labels of food products due to what they have not many responsibilities as a family, house, and work; in this sense, they can read with more patient. From the statistical analysis, it was concluded that gender, age, and monthly income were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), unlike the education variable, which was highly significant (p<0.001).

On the other hand, in relation to "best before", 65.1% of 18-24 years old, 61.3% of bachelor/graduate, always read, and 50% of people over 56 years of age do not read (

Figure 1B), possibly this last is due to their age; also, it probably is due to the idiosyncrasy of reading too. According to statistical results, age and education were significant (p < 0.05). In general, women were more committed to reading the expiration dates (“expiration date” and “best before”) than men, similar results were found by Kavanaugh and Quinlan [

4]. Probably, this result indicated that women have a greater commitment to their family's health.

Majorly, the consumers don't read the “expiration date” for lack of time (

Figure 1C). Also, the consumers mentioned that the numbers and letters are not visible easily. In addition, 23.1% of people over 56 years of age answered that not interested to read “expiration date”. Thus, a lack of interest could lead to food waste and food insecurity. The variables gender and monthly income were not significant (p > 0.05), while age and education were statistically significant (p < 0.05). In the same way, it is observed in

Figure 1D, that the lack of time, letters not visible, and lack of interest, were the reasons for not reading "best before". Another reason for not reading was that consumers do not understand the term. Prieto et al. [

24] found that lack of time (38.9%), lack of interest (27.1%), difficulty reading (18.1%), and difficulty understanding (8.3%) were the main reasons for not reading the expiry dates. These situations could affect the well-being of the population. In consequence, time is a factor so important during the buy of products. Also, the lack of consumer education leads to them not reading the expiration dates.

3.2. Consumer behavior towards expired food

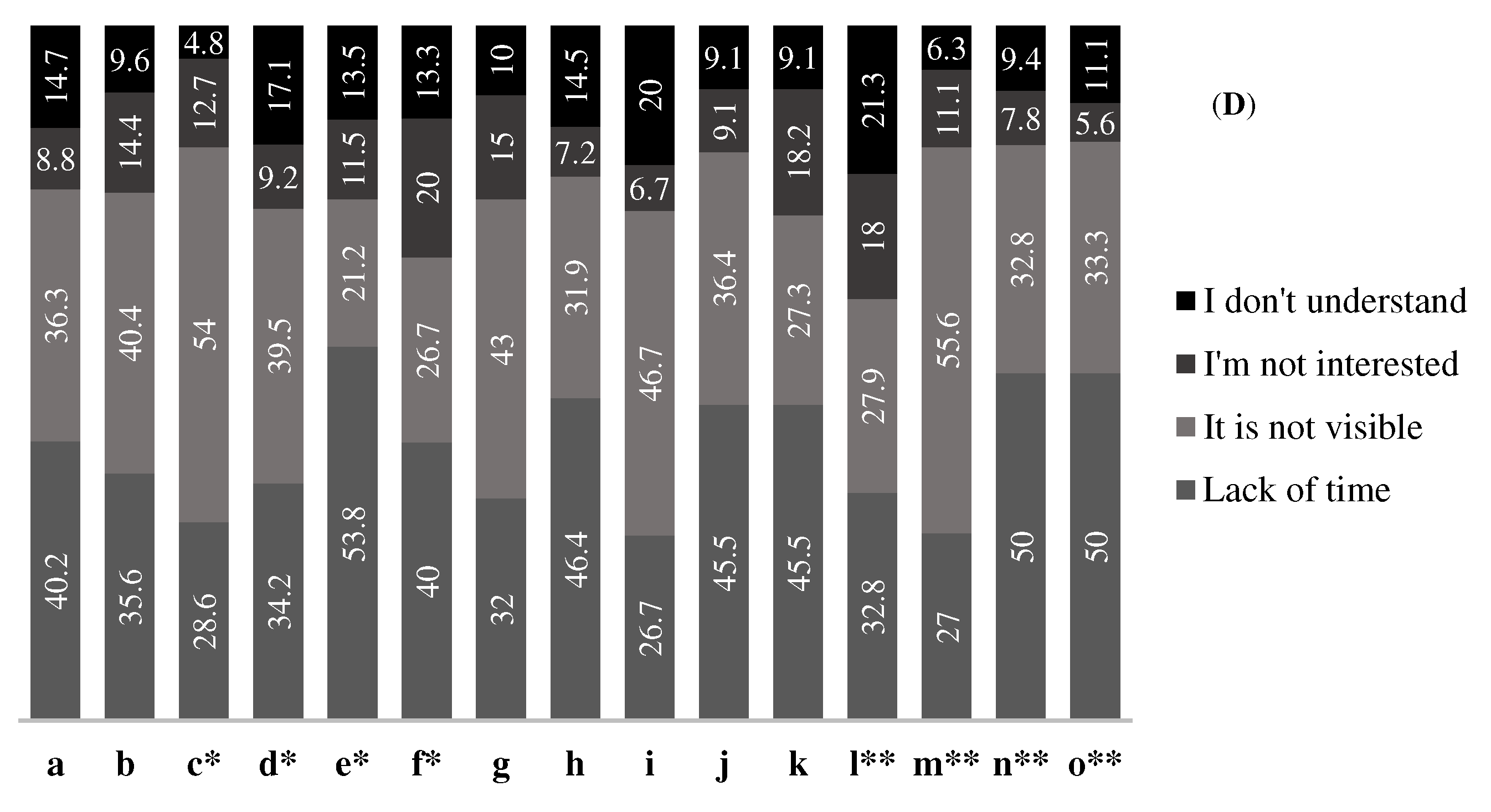

The selected expired food products were four (Supplementary 1: questions 10 and 11), two with the label "expiration date" (Fresh milk and eggs) and two with the label "best before" (UHT milk and mayonnaise) (

Figure 2); these four products had the following characteristics: containers or closed packages in good condition and legible labels.

As above to term "expiration date". Fresh milk (

Figure 2A); 68.8% of women, 65.3% of people 40-55 years old, 81.5% of people with monthly income >

$1842, and 90.7% of people with a master/doctorate, had the behavior of discarding the expired product. From the statistical analysis, all variables were significant. The gender, age, and education were highly significant (p < 0.001). Therefore, it was observed that the majority of consumers chose to discard the expired product. This was probably due to the fear factor of consuming an expired product. Another possible reason could be the product type. Similarly, Van Bockstael et al. [

23] mentioned that 40% of the respondents stated to discard milk with an expired date; in relation to this, Samotyja and Sielicka-Różyńska [

25] indicated that milk rejection is strongly influenced by its odor when it is an expired product. As above, a lower percentage of consumers had the behavior of consuming an expired product. Another percentage of consideration had the behavior of processing (i.e., mixing, and cooking with other foods), testing, and consuming the expired product. However, it is not reasonable and sensible, to taste or process this type of expired food, as mentioned by Melini et al. [

26]. Fresh milk is a sensitive product and requires many safety and storage conditions to maintain its microbiological quality [

27].

From the results, regarding the egg (

Figure 2B), more than 60% of the total respondents had the behavior of discarding the product. Women (79.6%), people with monthly income >

$1842 (88.9%), and people with a master/doctorate (92.6%), had a behavior of discarding this expired product. The gender and level of education were highly significant (p < 0.001). Women discarded more expired food than men; in this sense, women show rational behavior and have greater criteria to discard expired food with the term "expiration date". Women perform a better discard procedure for this expired food than men [

28,

29,

30,

31]. These results show that people with higher education had a rational and sensible behavior with respect to this type of expired product; possibly because the egg is a highly perishable food, and it can be contaminated with different pathogens, at any stage of the production chain [

32,

33]. Likewise, Feddern et al. [

34], mentioned that the internal quality of the egg decreases as the storage time progresses. Likewise, Ankiel and Samotyja [

13], mentioned that the only reasonable behavior for consumers is to discard this type of food.

Regarding UHT milk with the term "best before" (

Figure 2C), 65% on average, of women and men, had the behavior of discarding the product. Likewise, it was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in relation to gender. However, the variables of monthly income and level of education had a significant effect on the behavior of discarding expired food. In general terms, more than 50% of those surveyed had the behavior of discarding the expired product. Possibly, this consumer behavior was due to fear of consuming an expired product. According to Melini et al. [

26], UHT milk is a product that has been subjected to a sterilization process at 135–150°C, for 1-4 seconds; also, this type of product is aseptically packaged, it is even called a commercially sterile product. Therefore, the consumer's behavior of discarding is irrational and senseless due to that these products could be reprocessed to be consumed. In another way, the principal change caused by reprocessing is the organoleptic aspect of the product.

From the results, regarding mayonnaise (

Figure 2D), 72.1% of the men had the behavior of discarding the product. The gender variable had a significant effect (p < 0.01) on the behavior of discarding. Regarding the other variables, the monthly income and level of education were also significant, unlike the age variable, which was not significant (p > 0.05). Level of education variable was highly significant (p < 0.001). University students (83.5%) and people with completed high school (78.7%) had the behavior of discarding expired products. These results were very high; thus, it could infer that the lack of education causes food waste. Gorji et al. [

35] mentioned that mayonnaise is a relatively safe product, due to its acidic pH (around 4.8); likewise, Mirzanajafi-Zanjani et al. [

36] indicated that this type of product is manufactured and designed with special techniques, such as: reduction of oxygen concentration, use of packaging with good light barrier properties, and the use of antioxidants, to avoid loss of its quality. For such reasons, and in relation to outcomes of this investigation, discarding expired product is not justified; thus, the behavior of consumers to discard would not be correct, due to that these foods could be used in another way (e.g., mixing and cooking with other foods) to be consumed.

Zielińska et al. [

6], investigated the microbiological, physical-chemical and sensory quality, before and after the expiration date "best before" of the products: UHT milk and mayonnaise; in their results they found that the products are safe from the microbiological point of view and do not represent any risk to health. However, these products could lose sensory qualities (change in smell, consistency and taste). In addition, the products could be consumed safely, even 6 months after their expiration date, without causing health risks. In relation to this topic, Trząskowska et al. [

37] concluded that the most appropriate behavior is to try and then consume the product if it is appetizing; additionally, they mentioned that discarding these products is irrational and senseless. In this sense, conscious consumption policies and better education of the population must be adopted to avoid discarding them. Additionally, Ankiel and Samotyja [

13], mentioned that the consequences of irrational consumer behavior are associated with the generation of food waste.

3.3. Health risks for consuming expired food

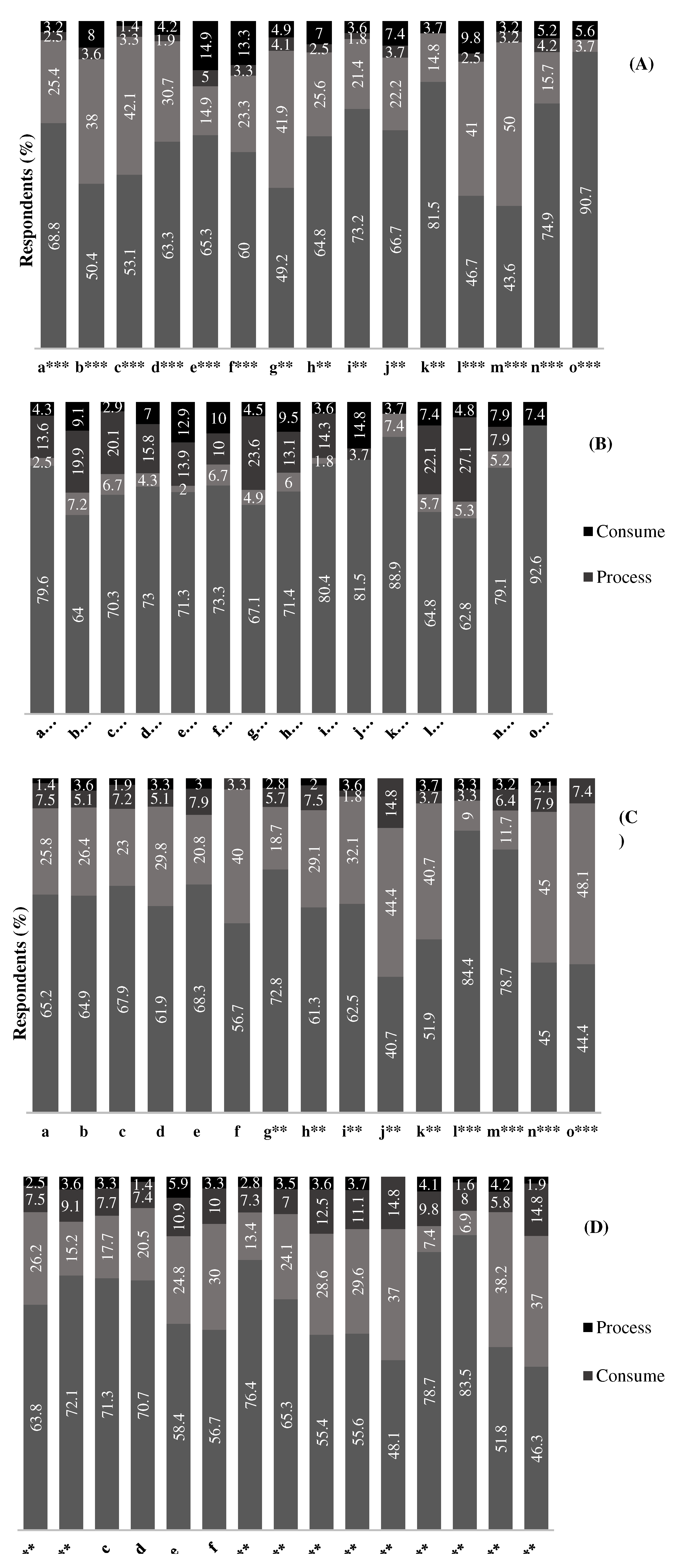

For expired products with the term "expiration date" (

Figure 3A), approximately more than 35% of the respondents answered the alternative "all of the above", i.e., the perception of consumers by consume expired products would cause stomach upset, vomiting, gas, intoxication, and malnutrition. Likewise, none of the respondents answered the alternative "none of the above". In addition, in approximately 44% of women and men had low knowledge about health risks; also, the gender and monthly income were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In contrast, the variables age and level of education were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Thus, these results shown low level of knowing about health risks. Samotyja and Sielicka-Różyńska [

25] indicated that consumers should be aware of the health risks by consuming expired food products with the term “expiration date”; also, they mentioned that all these risks are due to the growth of microorganisms within the expired product [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Therefore, the education for consumers about health risks is a fundamental homework. The education (highly significant, p < 0.001) had a predominant effect on perception the health risks by consuming expired food; in this regard, Toma et al. [

8], mentioned that consumers check the expiration date of food to assess whether it is safe or not for their health; also, they indicated that consumers reject the product with passed expiration date or do not have the expiration date clearly written.

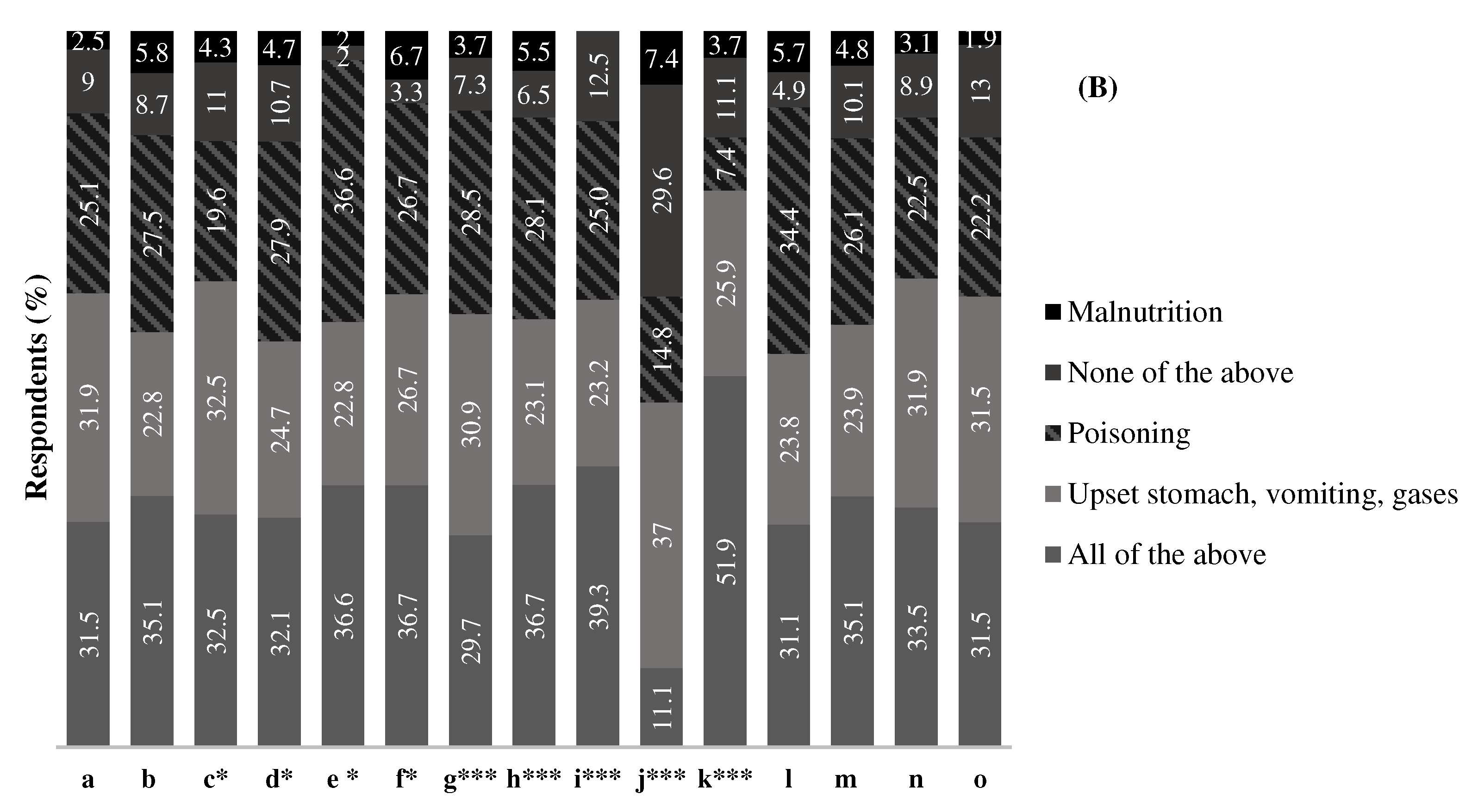

As above with the term "best before".

Figure 3B shows that 35.1% of men, 31.5% of women, and 51.9% of people with monthly incomes >

$1842 answered the alternative “all of the above”, i.e., consuming expired products would cause stomach upset, vomiting, gas, intoxication, and malnutrition. Also, the results show that men and women do not clearly differentiate the health risks by consuming expired products. Food products, under the term "best before", with passed expired date, remain safe for consumption, from a microbiological point of view, and only their sensory characteristics should determine their acceptability for consumption. Also, consumers are often confused about the different expiration date terms; in consequence, they tend to discard expired foods [

42].

Therefore, from the results obtained, it could infer that consumer do not know the exact risks caused by consuming expired food with the term "best before". Thus, this contributes to food waste and food insecurity. Likewise, correct consumer perception of the health risks associated with expired food will reduce food waste, as indicted by Ankiel and Samotyja [

13]. Also, these types of expired foods with the term "best before" could be consumed without nothing risk to health. Consumers should not waste these foods.

Expired foods are easy to contaminate due to that their components (proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates) are more susceptible to changes in temperature, and humidity, due to the decomposition process; thus, these expired foods must be manipulated with more care; likewise, Gizaw [

43] indicated that poor hygiene or handling of the food may generate contamination to foods [

40,

44,

45]. Chan et al. [

20] mentioned that these problems occur mostly in places where there is no education on the topic of risk to health. Melbye et al. (2016) mentioned that food safety policies play an important role in these points. Thus, a good food safety policy and education on the handling of expired food ("best before") will prevent health problems, food waste, and lack of food, in the countries.

4. Conclusions

Approximately 73% of the total number of respondents consider it important to verify the "expiration date" and 40% consider it important to verify "best before". Forty-five percent of all those surveyed consider that both terms mean the same thing. Sixty-seven percent and forty-five percent of the total number of respondents correctly identified the definitions of "expiration date" and "best before", respectively. In this sense, there is difficulty to punctually differentiate the meaning between both terms of expiration dates. Therefore, the level of understanding of the terms by the respondents is low. Respondents do not read due to lack of time, and it is not easily visible. Also, expiration dates are not found quickly due to a lack of visibility and clarity. Therefore, they are not aware that expired food products with the term “expiration date” cannot be consumed, while expired food products with the term “best before” can be consumed and it should not be wasted or thrown away to garbage. The health risks perceived by those surveyed for consuming expired food under the term "expiration date" are upset stomach, vomiting, gas, intoxication, and malnutrition. Unfortunately, these risks are also perceived in expired food products under the term "best before". In the latter case, the perception of danger to health is unfounded and without any knowledge. However, despite the perceived health risk, consumers show a lack of consistency in their behaviors towards expired foods. Thus, it is necessary to include the need for training and educational policies in the theme.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.S.C.R; methodology, A.R; validation, L.O.M, A.S.M, T.G.H; formal analysis, D.G, L.O.M, J.S.C.R, A.R, A.S.M, T.G.H; investigation; L.O.M; resources, L.O.M, J.S.C.R, A.R, A.S.M, T.G.H ; data curation, D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G., J.S.C.R; writing—review and editing, D.G.; visualization, A.S.M., T.G.H.; supervision, L.O.M., T.GH.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank PhD. Silvia Pilco Quesada for their assistance on this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Food Loss and Food Waste 2019.

- Ishangulyyev, R.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. Understanding Food Loss and Waste—Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food? Foods 2019, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, U.; Loy, J.; Ren, Y. Food Loss and Waste: Some Guidance. EuroChoices 2020, 19, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.; Quinlan, J.J. Consumer Knowledge and Behaviors Regarding Food Date Labels and Food Waste. Food Control 2020, 115, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.L.; Qi, D.; Roe, B.E. Food-Related Routines, Product Characteristics, and Household Food Waste in the United States: A Refrigerator-Based Pilot Study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 150, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, D.; Bilska, B.; Marciniak-Łukasiak, K.; Łepecka, A.; Trząskowska, M.; Neffe-Skocińska, K. Consumer Understanding of the Date of Minimum Durability of Food in Association with Quality Evaluation of Food Products after Expiration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.; Rice, C.; Schklair, A.; Greenberg, S.; Leib, E.B. Misunderstood Food Date Labels and Reported Food Discards: A Survey of U.S. Consumer Attitudes and Behaviors. Waste Management 2019, 86, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, L.; Costa Font, M.; Thompson, B. Impact of Consumers’ Understanding of Date Labelling on Food Waste Behaviour. Oper Res Int J 2020, 20, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food Waste Prevention in Europe – A Cause-Driven Approach to Identify the Most Relevant Leverage Points for Action. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Phillips, A.; Shah, P. Unclarity Confusion and Expiration Date Labels in the United States: A Consumer Perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2017, 35, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Messer, K.D.; Kaiser, H.M. The Impact of Expiration Dates Labels on Hedonic Markets for Perishable Products. Food Policy 2020, 93, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madilo, F.K.; Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Parry-Hanson Kunadu, A.; Tano-Debrah, K. Self-Reported Use and Understanding of Food Label Information among Tertiary Education Students in Ghana. Food Control 2020, 108, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankiel, M.; Samotyja, U. The Role of Labels and Perceived Health Risk in Avoidable Food Wasting. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Miao, R.; Weis, C. Seeing Is Not Believing: Perceptions of Date Labels over Food and Attributes. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2018, 24, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-Perales, N.S.; Dal’ Magro, G.P. Quantification of Food Losses and Waste in Peru: A Mass Flow Analysis along the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Analysis of the Behaviors of Polish Consumers in Relation to Food Waste. Sustainability 2019, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinie, C.; Biclesanu, I.; Bellini, F. The Impact of Awareness Campaigns on Combating the Food Wasting Behavior of Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Rickard, B.J.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.-T. Food Waste: The Role of Date Labels, Package Size, and Product Category. Food Quality and Preference 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila, E.; Avorgah, S.; Adigbo, E. Exploring Consumer Knowledge and Usage of Label Information in Ho Municipality of Ghana. European Scientific Journal 2013, 9.

- Chan, E.Y.Y.; Lam, H.C.Y.; Lo, E.S.K.; Tsang, S.N.S.; Yung, T.K.C.; Wong, C.K.P. Food-Related Health Emergency-Disaster Risk Reduction in Rural Ethnic Minority Communities: A Pilot Study of Knowledge, Awareness and Practice of Food Labelling and Salt-Intake Reduction in a Kunge Community in China. IJERPH 2019, 16, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSA (Food Standards Agency) Understanding Northern Ireland Consumer Needs around Food Labelling. 2016.

- Beneke, J.; Greene, A.; Lok, I.; Mallett, K. The Influence of Perceived Risk on Purchase Intent – the Case of Premium Grocery Private Label Brands in South Africa. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2012, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boxstael, S.; Devlieghere, F.; Berkvens, D.; Vermeulen, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Understanding and Attitude Regarding the Shelf Life Labels and Dates on Pre-Packed Food Products by Belgian Consumers. Food Control 2014, 37, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Castillo, L.; Royo-Bordonada, M.A.; Moya-Geromini, A. Information Search Behaviour, Understanding and Use of Nutrition Labeling by Residents of Madrid, Spain. Public Health 2015, 129, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samotyja, U.; Sielicka-Różyńska, M. How Date Type, Freshness Labelling and Food Category Influence Consumer Rejection. Int J Consum Stud 2021, 45, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Ruzzi, M. Raw and Heat-Treated Milk: From Public Health Risks to Nutritional Quality. Beverages 2017, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Toma, L.; Barnes, A.P.; Revoredo-Giha, C. The Effect of Date Labels on Willingness to Consume Dairy Products: Implications for Food Waste Reduction. Waste Management 2018, 78, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivupuro, H.-K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of Socio-Demographical, Behavioural and Attitudinal Factors on the Amount of Avoidable Food Waste Generated in Finnish Households: Factors Influencing Household Food Waste. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted Food: U.S. Consumers’ Reported Awareness, Attitudes, and Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household Food Waste Behaviour in EU-27 Countries: A Multilevel Analysis. Food Policy 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out Food Waste Behaviour: A Survey on the Motivators and Barriers of Self-Reported Amounts of Food Waste in Households. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, T.-H.; Wu, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tan, F.-J. Effects of Egg Washing and Storage Temperature on the Quality of Eggshell Cuticle and Eggs. Food Chemistry 2016, 211, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf Eddin, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Tahergorabi, R. Egg Quality and Safety with an Overview of Edible Coating Application for Egg Preservation. Food Chemistry 2019, 296, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddern, V.; Prá, M.C.D.; Mores, R.; Nicoloso, R.D.S.; Coldebella, A.; Abreu, P.G.D. Egg Quality Assessment at Different Storage Conditions, Seasons and Laying Hen Strains. Ciênc. agrotec. 2017, 41, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani Gorji, S.; Calingacion, M.; Smyth, H.E.; Fitzgerald, M. Comprehensive Profiling of Lipid Oxidation Volatile Compounds during Storage of Mayonnaise. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 4076–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzanajafi-Zanjani, M.; Yousefi, M.; Ehsani, A. Challenges and Approaches for Production of a Healthy and Functional Mayonnaise Sauce. Food Sci Nutr 2019, 7, 2471–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trząskowska, M.; Łepecka, A.; Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Marciniak-Lukasiak, K.; Zielińska, D.; Szydłowska, A.; Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Changes in Selected Food Quality Components after Exceeding the Date of Minimum Durability—Contribution to Food Waste Reduction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kirk, M.D.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gibb, H.J.; Hald, T.; Lake, R.J.; Praet, N.; Bellinger, D.C.; De Silva, N.R.; Gargouri, N.; et al. World Health Organization Global Estimates and Regional Comparisons of the Burden of Foodborne Disease in 2010. PLoS Med 2015, 12, e1001923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbye, E.L.; Onozaka, Y.; Hansen, H. Throwing It All Away: Exploring Affluent Consumers’ Attitudes Toward Wasting Edible Food. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2017, 23, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Hernandez, A.; Galagarza, O.A.; Álvarez Rodriguez, M.V.; Pachari Vera, E.; Valdez Ortiz, M.D.C.; Deering, A.J.; Oliver, H.F. Food Safety in Peru: A Review of Fresh Produce Production and Challenges in the Public Health System. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 3323–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, N.; Anihouvi, V.; Hounhouigan, J.; Matsheka, M.I.; Sekwati-Monang, B.; Amoa-Awua, W.; Atter, A.; Ackah, N.B.; Mbugua, S.; Asagbra, A.; et al. Prevalence of Foodborne Pathogens in Food from Selected African Countries – A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2017, 249, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, R.; Balestrini, C.G.; Baum, M.D.; Corby, J.; Fisher, W.; Goodburn, K.; Labuza, T.P.; Prince, G.; Thesmar, H.S.; Yiannas, F. Applications and Perceptions of Date Labeling of Food: Date Labeling of Food…. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2014, 13, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, Z. Public Health Risks Related to Food Safety Issues in the Food Market: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ Health Prev Med 2019, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylvia, A.B.; RoseAnn, M.; John, B.K. Hygiene Practices and Food Contamination in Managed Food Service Facilities in Uganda. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2015, 9, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Aspinall, W.; Cooke, R.; Corrigan, T.; Havelaar, A.; Angulo, F.; Gibb, H.; Kirk, M.; Lake, R.; et al. Attribution of Global Foodborne Disease to Specific Foods: Findings from a World Health Organization Structured Expert Elicitation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).