1. Introduction

Unequivocally, the world has been determined to achieve a better and an inclusive sustainable future, predominately for developing nations, which are more in a vulnerable position of poverty and inequality, inter alia, which is evident in various development plans. For instance, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), from the global perspective, precisely Goals 1, 8, and 10, which seek to end poverty, promote decent work and economic growth, and reduce inequality, respectively, by 2030 (SDGs, 2019). From the national perspective, the Namibian government seeks to reduce poverty and inequality by 2030 as documented in the Namibia’s Vision 2030 Plan (National Planning Commission [NPC], 2017).

However, the issue of unemployment continues to be a global critical concern to a large extent of emerging states (Alarifi et al., 2019; Iwu & Opute, 2019; Sarmah et al., 2021), where Namibia is no exception. To break it down, unemployment trends on a global level stood at about 197.7 million, accounted for 5.6% in 2016 and reduced slightly to 192.7 million in 2017, while in 2018 and 2019, the estimates were 192.3 million and 193.6 million, correspondingly (International Labor Organization [ILO], 2019). From the viewpoint of developing states, unemployment was estimated at 15.6 million in 2017, with persistence to rise in 2018 and 2019 to 16.1 million and 16.6 million, respectively (ILO, 2017). For Sub-Saharan Africa, unemployment stood at 6.18% in 2019 and 6.17% in 2020 (Ayinde, 2020). Currently, unemployment in Namibia stands at 34% with youth unemployment at 47.4% (Namibia Statistics Agency, 2023).

While unemployment can have devastating effects on macroeconomic performance (Nautwima & Asa, 2021a), it, however, cannot always be viewed as an obstacle to economic growth in such a manner that it encourages people to venture into business activities; and as they grow, they can create more jobs and eventually reduce unemployment (Gawel, 2020). However, such businesses suffer various impediments, mainly those associated with funds, which hinder their ability to grow and serve to that effect (Nautwima & Asa, 2021b). On that ground, academic and practical researchers have been indefatigably aspiring to determine the relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment. Briefly, the policy debate on how to tackle the chronic issue of unemployment revolves around the refugee effect that perceives unemployment as a push factor for emerging in entrepreneurship and the Schumpeter effect that supposes entrepreneurship as a notable player in reducing unemployment (Cheratian et al., 2020; Dvouletý, 2017; Emami-Langroodi, 2018; Grigorescu et al., 2020; Payne & Mervar, 2017; Prasetyo, 2021).

Nonetheless, previous investigations reveal inconsistent and ambiguity findings (Feki & Mnif, 2019; Halicioglu & Yolac, 2015; Leitão & Capucho, 2021; Saridakis et al., 2016), which indicates a contradictory gap, following the notion of Miles (2017) on research gaps. Thus, it remains unclear whether (a) an increase in entrepreneurship leads to a reduction in unemployment; (b) a rise in unemployment accelerates entrepreneurial activities; or (c) a high rate of unemployment slows down entrepreneurial activities. Hence, the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship continues to invite further debate among scholars and policymakers (Cheratian et al., 2020).

Moreover, the literature documents a paucity of studies, if not none, that addressed the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship within the Namibia context, as early studies focused on economies outside the Namibian borders. As a results, the findings of these studies cannot be generalized to Namibia, given the differences in entrepreneurial ecosystems and economic status between countries. Based on the taxonomy of Miles (2017) on research gap, this implies an empirical gap. Hence, the essentiality of this study to analyse the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship in terms of business formation within the Namibian context and establish the direct of causality using Namibia as a testing hub. The end view is to have constructed a model that defines the nature of the existing relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship.

In a nutshell, achieving these objectives is expected to aid policymakers in devising evidence-based policies in addressing the issue of unemployment. That is, to concentrate on lowering regulatory the barriers and the cost of business formation if unemployment pushes entrepreneurship or to concentrate on economic success to mitigate the unpleasant consequences of a recession if increased unemployment reduces entrepreneurial chances (Apergis & Payne, 2016). Furthermore, the study is also expected to enrich the literature by addressing the twin research gaps of contradiction and empirical gaps. Hence, the significance of this study. This scholarly work is structured into five sections, the second section that follows this introduction section revies the theoretical and empirical literature. Subsequently, section 3 describes the data and methodology for the empirical estimation of the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship in terms of business formation.

Section 4 analyzes the data, presents the results, and discusses the findings. Finally, section 5 provides conclusions and recommendations of the study.

2. Literature Review

Unemployment has long been a worldwide challenge that hits the core of economies, leaving an unfavorable indelible mark on sectors, society, livelihoods, businesses, and people (Padi & Musah, 2022). Hence, policymakers have been obliged to seek theoretical underpinnings for effective measures to reduce the unemployment rate in developing countries. In that frame of reference, entrepreneurship has been deemed as a remedy for economic and social challenges (Kang & Xiong, 2021; You et al., 2017). To better understand the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship, this study was rooted in the theoretical debate among the simple theory of the refugee effect, and the Schumpeter effect. Moreover, the study augmented the arguments of the theoretical literature with empirical evidence from prior studies.

2.1. Theoretical Review

The relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship is a topic of vigorous economic debate. This debate stems from the refugee effect, which originated from the simple theory of income choice and posits that increased unemployment will lead to an increase in entrepreneurship as the opportunity cost of starting a business is less than being unemployed (Cheratian et al., 2020; Emami-Langroodi, 2018; Prasetyo et al., 2022; Prasetyo & Kistanti, 2020; Tang, 2022). This signifies that unemployed people find entrepreneurship to be a feasible alternative of living in a saturated economy that struggles to absorb jobseekers. Hence, this phenomenon is referred to as the recession-push effect (Cheratian et al., 2020; Payne & Mervar, 2017), as it demonstrates the positive relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship with the direct of causality running from unemployment, making the calamity of unemployment a catalyst for new business ventures.

In the same body of literature, a counterargument contends that unemployed individuals lack the necessary endowments of human capital and entrepreneurial talent that drive business start-ups and their sustainability, implying that high unemployment does not necessarily increase entrepreneurial activities (Feki & Mnif, 2019; Halicioglu & Yolac, 2015). In that context, a languishing economy and perplexity of business formation can also hinder the entrepreneurial success (Aceytuno et al., 2020; Nautwima & Asa, 2021b). Thus, this argument signifies a negative relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship. That is, as unemployment rises, firms suffer a weaker market demand, which increases the likelihood of business failure, forcing entrepreneurs to withdraw from operation (Cheratian et al., 2020).

The second theory underpinning the study is the Schumpeter effect, which implies that the formation of new businesses reduces unemployment (Aku-sika, 2020; Camba, 2020; Emami-Langroodi, 2018; Gautam & Lal, 2021; Grigorescu et al., 2020; Payne & Mervar, 2017; Prasetyo & Kistanti, 2020; Ragmoun, 2023). This notion is referred to as a prosperity-pull theory, asserting that a higher potential returns to entrepreneurial activity results in an increase in new business formation with a high possibility of growth and high chances of hiring more employees, which will eventually reduce unemployment (Payne & Mervar, 2017). Hence, the theory demonstrates a positive relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship with the direction of causality running from entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, this phenomenon is fascinated to the dynamics of economic performance, as the success of entrepreneurship aligns with an economy experiencing strong economic growth (Aceytuno et al., 2020). In brief, the refugee effect is mostly present in developing and emerging economies while the Schumpeter effect is mainly existent in developed nations (Acs et al., 2017, 2018; Bosma et al., 2018; Boudreaux & Caudill, 2019; Ivanovic-Djukic et al., 2018; Setiawan & Aritenang, 2019). Given that, this study relied on the conceptions of the refugee and Schumpeter effects to determine the direction of causality between unemployment and entrepreneurship in Namibia, which is absent in the literature, based on our knowledge of exploration.

2.2. Empirical Literature Review

The literature presents several studies on the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship. In general, entrepreneurship induces new venture creation and growth (Halid et al., 2020; Maritz et al., 2020). Hence, the need for supporting entrepreneurial ecosystems for the realization of economic growth (Acs et al., 2018) is essential in developing countries. However, from the global context, Galindo da Fonseca (2022) argues that while unemployment doubles the likelihood of unemployed people to start new businesses in Canada, it’s effect on job creation is minimal whereas the chances of failing are high. Although these results agree with the notion of recession-push theory on a direct nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship, the possibility of high failure rate aligns with the critics of refugee effect that unemployed people do not possess the required resources for successful business start-ups and sustainability. Also, supporting the postulation of the recession-push effect is the findings of Payne and Mervar (2017), which reveal that an increase in unemployment Granger causes self-employment through entrepreneurship in Croatia. Furthermore, the findings of Ragmoun (2023) also demonstrate that unemployment promotes entrepreneurship in developed countries. Besides that, Cheratian et al. (2020) discovered a long run negative impact of unemployment on entrepreneurial activity in Iran, which opposes the recession-push effect. This signifies that high unemployment enhances the risk of business failure, which forces entrepreneurs to pull out from being self-employed.

Against the refugee effect, Camba (2020) reveals that in the short-run, an increase of entrepreneurship decreases unemployment in Philippines. These results are an indication of the existence of the Schumpeter effect in the short run. In a nutshell, the results are consistent with the findings of previous studies (Fritsch & Wyrwich, 2017; Stuetzer et al., 2018), which emphasize on the cruciality of entrepreneurship in enhancing employment opportunities in developed countries. In the same context, Prasetyo (2021) found the validity of the Schumpeter effect in Indonesia, where entrepreneurship addresses the issue of unemployment, while Apergis & Payne (2016) reveal a bidirectional causal effect between entrepreneurship and unemployment in the United States.

Finally, Grigorescu et al. (2020) discovered ambiguity results in Romania, revealing the presence of both the refugee effect and Schumpeter effect among different groups of unemployed people. This led to the conclusion that although unemployment serves as an inclusion push factor for entrepreneurship, it is ineffective for others as self-employment reflects a strong risk aversion and a poor start-up impact. Overall, the ambiguity of these results is reflected in the notion of Halicioglu and Yolac (2015), which emphasizes that the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship is ambiguous after revealing the presence of both hypotheses of the refugee effects among 28 OECD countries. That is, an increase in entrepreneurial activities due to a rise in unemployment rate in Belgium, Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom and a decline in entrepreneurship because of an increase in unemployment rate in Greece, Luxembourg, and Portugal in the long run, while the remaining countries did not exhibit a long-run relationship.

From the continental view, Padi and Musah (2022) assessed the extent to which entrepreneurship can sufficiently reduce unemployment in Ghana using a systematic literature review approach and found that entrepreneurship alone has a potential to reduce unemployment, predominantly when there is innovation and stable economic prosperity. While the results support the notion of the Schumpeter effect, which presumes entrepreneurship to be a remedy for unemployment challenge, the outcome are, however, likely to take a minimum of approximately 5 years to be evident (Padi & Musah, 2022). Moreover, the results are also in line with the emphasize of Aku-sika (2020) that entrepreneurship drives economic growth by addressing social challenges. Asides of that, Feki and Mnif (2019) reveal the presence of both the refugee effect and Schumpeter effect in Tunisia, where an increase in unemployment results in self-employment and an increase in self-employment reduces unemployment. These results are in support of the assertation of other studies, which underscore the ambiguity of the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship (Grigorescu et al., 2020; Halicioglu & Yolac, 2015). Nonetheless, the literature documents a dearth of evidence from the Namibian context.

2.3. Research Gaps

As emerged from the literature, evidence presents mixed results, which side with both the refugee and Schumpeter effects regardless of the countries’ category of development. For instance, the refugee effects observed in developed countries like Canada (Galindo da Fonseca, 2022) and Belgium, Sweden, and the UK (Halicioglu & Yolac, 2015), inter alia, and the Schumpeter effect in developing states like Ghana (Padi & Musah, 2022) and Philippines Camba (2020), among others. Overall, this evidence contradicts the assertion of early studies (Acs et al., 2017, 2018; Bosma et al., 2018; Boudreaux & Caudill, 2019; Ivanovic-Djukic et al., 2018; Setiawan & Aritenang, 2019), which highlight that the refugee effect exists in developing and emerging economies while the Schumpeter effect is found in developed countries. Furthermore, the existing ambiguous evidence of the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship implies a contradictory gap, in reference to the taxonomy of Miles (2017) on research gaps, which is a call for further investigations.

Finally, the existence of an empirical gap based on the notion of Miles (2017) is also evident from a comprehensive review of the literature given a paucity of evidence from the Namibian perspective. This study served to bridge these gaps by assessing the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship within the Namibian context and provide guidelines to policymakers for evidence-based policy devising and assimilation. Thus, the study hypothesizes that:

H0: Unemployment does not induce entrepreneurship in Namibia.

H1: Unemployment induces entrepreneurship in Namibia.

3. Data and Methods

This study used time series data, which were collected from the World Bank database to investigate the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship in Namibia. The variables included unemployment in terms of the annual rate (ILO estimates), entrepreneurship as the number of yearly business formation, and cost of business start-up procedures as a percentage of Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. We used the data for 11 years, running from 2006 to 2016, since the data for business formation were only readily available for that period. In that light, we transformed the annual data into quarterly data to meet the sample criterion for quantitative studies that should be at least 30 (Nelson & Plosser, 1982). In that context,

Table 1 illustrates the variables’ descriptive statistics.

Given that, the general function of the model specification was specified as:

where UNEMP is the rate of unemployment, BF represents business formation, while CBSP is the cost of business start-up procedures.

Thus,

where,

is Unemployment (UNEMP),

represents

(Business Formation (BF), Cost of Business Start-up Procedures (CBSP),

is the Parameter Estimates,

is the Stochastic Error Term, while

represents Time.

3.1. Econometric Procedure

To analyse the data, we employed several econometrical analyses. They include the unit root test, Johansen-Juselius test of cointegration, Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model, and Pairwise Granger causality test, as well as the stability test using E-Views software. In so doing, we used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to determine the optimum number of lags for each variable.

3.1.1. Unit Root Test

Often, time-series data are non-stationary. However, estimations are likely to be spurious when the analyses are performed on non-stationary data (Granger & Newbold, 1974). Accordingly, the unit root test was applied for stationarity testing to show the presence or absence of unit root in the data. Generally, the absence of unit root in the data gives an indication of applying the VAR model to estimate the short-run relationship between the variables. In contrast, the presence of unit root in the data is a call for a cointegration test to determine whether the variables are cointegrated in the long-run or not. For this study, we applied the widely used Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test of stationarity (Phiri et al., 2020), as it accounts for serial correlations (Dickey & Fuller, 1981), which we have complimented with the Phillips–Perron (PP) tests of stationarity to ensure robustness of the results. The null hypothesis for both the ADF and PP tests asserts that the data are not stationary (have a unit root) while the alternative hypothesis states that the null hypothesis is not true. In that context, the null hypothesis is rejected when the t-statistics exceeds the t-critical value (in absolute values) (Dickey & Fuller, 1981; Phillips & Perron, 1988).

3.1.2. Johansen-Juselius Cointegration Test

Cointegration test is essential as it determines the suitable model for estimations based on time series data (Phiri et al., 2020). Thus, we performed the Johansen-Juselius test of cointegration to estimate if there exists a long-run relationship between the variables in the model. The preference of this test lies in its ability of side-stepping the issue of selecting the dependent variable, its ability to detect multiple cointegration vectors, and its appropriateness for variables integrated of the same order of cointegration I(1) (Johansen & Jeselius, 2009). Following that, the null hypothesis of the Johansen-Juselius cointegration indicates that the absence of cointegration, which is a call for the short-run estimations while the alternative hypothesis asserts the presence of cointegration, which is a call for the long-run estimation. In that context, the null hypothesis is rejected when the values of Trace and Max-Statistics are greater than the critical values at 5% (Johansen & Jeselius, 2009).

3.1.3. Vector Autoregressive Model

Based on the cointegration test results, we performed the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model to estimate the short-run relationships between the variables. In this regard, we specified the VAR model as follows:

Therefore, the VAR equations were:

3.1.4. Pairwise Granger Causality Test

We applied the Pairwise Granger causality, which determines the causal relationship between the variables (Granger, 1969). In general, it is said that X Granger causes Y, given that Y=f(X) if the previous data of X helps to predict Y (Amornbunchornvej et al., 2019). This study applied the pairwise Granger causality test to establish the direction of the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship (business formation) in Namibia. Hence, the null hypothesis of the Granger causality demonstrates that X does not Granger cause Y, while the null hypothesis indicates that X Granger causes Y. The null hypothesis is rejected when the probability value is less than 5% (Granger, 1969). Based on that, Granger causality equations are simplified as follows:

where

and

represent the uncorrelated stochastic terms, while

,

,

, and

denote the coefficients of the variables.

3.1.5. Diagnostic and Model Efficacy tests

To ensure the efficacy of the model, notably its error term with respect to serial correlation, heteroskedasticity, and normality tests. In detail, we used Breusch-Godfrey test for serial correlation to determine if the model suffers from serial correlation. The null hypothesis of this test indicates the absence of serial correlation, and it is rejected when the p-value falls below 5% (Wooldridge, 2004). Moreover, we also applied the heteroskedasticity test to measure whether there is constant variance around the error term (homoskedasticity). The null hypothesis of heteroskedasticity states that there is no heteroskedasticity (there is homoskedasticity), while the alternative hypothesis suggests the presence of heteroskedasticity. In that case, the null hypothesis is rejected when the probability value is less than a 5% significance level (Wooldridge, 2004). Finally, we have also measured the normality of the data using the Jarque-Bera test of normality. The null hypothesis of Jarque-Bera test of normality indicates that the data are not normally distributed while the alternative hypothesis states that the null hypothesis is not true. In that view, the null hypothesis is rejected when the p-value is less than 5% (Jarque & Bera, 1987).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Unit Root Results

Firstly, we transformed the data into their logged form to assume linearity and reduce wider variation. After that, applied both the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) test of a unit root for accuracy in testing whether the data are stationary or non-stationary.

Table 2 presents the unit root test results.

As shown in

Table 2, the results indicate that all the variables were not stationary in level forms for both the ADF and PP tests. Nonetheless, all the variables became stationary after differentiation. Hence, we rejected the null hypotheses of the unit root test for all the variables to indicate the absence of unit root in the data after the first difference. Since the result indicate that the all the variables exhibit the same order of integration [1(1)], we tested cointegration using the Johansen-Juselius test of cointegration.

4.2. Johansen-Juselius Cointegration Test Results

We relied on the Trace statistic and the Maximum Eigen statistic, which are respectively presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4 to determine whether the is cointegration among the equations. The asterisk denotes the number of cointegrated equation(s) [CE(s)].

As displayed in

Table 3, results show that the Trace statistic and Max-statistics values are all less than their Critical values at 5%, as portrayed in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. This signifies the absence of cointegration in all the equations. Thus, we failed to reject the null hypothesis to signify that there exist no long-run relationships between the variables. On that basis, we performed the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model to estimate the short run relationship between the variables.

4.3. Vector Autoregressive (VAR) Model Results

Table 5 presents the short run estimation results of the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model, where C represents the constants, while the values in the brackets represent the t-values. In that frame of reference, a t-value (in absolute values) greater than 1.96 implies that the relationship is statistically significant at 1 and/or 5% levels of significance, while a t-value equal to or less than 1.96 indicates that the relationship is not statistically significant (Hogg & Tanis, 2001).

In terms of significance, each variable was found to be statistically significant to the model of itself at a 1% level of significance in lag 1, given the absolute t-values all greater than 1.96 (LNUNEMP, 6.62347 > t-value 1.96; LNCBSP, 5.50062 > t-value 1.96; and LNBF, 6.30374 > t-value 1.96). Regarding the measure of impacts, the past realization of unemployment is associated with an 84.39% increase in unemployment on average, ceteris paribus. Moreover, the past realization of the cost of business start-up procedures accounts for a 78.44% increment in the cost of business start-up procedures on average, holding other factors constant. Lastly, the past realization of business formation is associated with an increase of 81.49% in business formation on average, ceteris paribus.

Apart from these significant impacts at 1%, the rest of the effects were found to be statistically significant at a 5% level of significance. In detail, a 1% increase in business formation in lag 1 and 2, respectively accounts for a rise of 5.36% and 4.84% in the cost of business formation procedures, keeping everything else unchanged, as well as a reduction of 0.57% and 0.98% in lag 1 and lag 2 of unemployment, respectively. Similarly, a 1 percent increase in unemployment leads to a rise of 13.43% and 10.29% in business formation in lag 1 and lag 2, respectively, as well as a reduction of 0.16% and 0.19% in lag 1 and lag 2 of cost of business start-up procedures, correspondingly. Finally, an increase of 1% in the cost of business start-up procedures reduces business formation by 3.18% in lag 1 and 3.94% in lag 2, as well as a fall of 0.26% and 0.12% in lag 1 and lag 2 of unemployment, respectively. In a nutshell, the short-run relationships between the variables are summarized in the following equations.

4.3. Diagnostics and Model Efficacy Test Results

Table 6 presents the diagnostics and model’s efficacy results from the Breusch–Godfrey LM test of autocorrelation, White’s heteroskedasticity test of homoskedasticity, and the Jarque-Bera test of normality.

As displayed in

Table 6, the p-values for Breusch–Godfrey LM White’s heteroskedasticity tests exceed 5% at 0.775 and 0.4131, respectively. Hence, we failed to reject the null hypotheses of these tests to demonstrate the absence of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity (indicating the presence of homoskedasticity). Finally, we rejected the hull hypothesis of the normality test given the Jarque-Bera of 0.0028, which is less than 5% to illustrate that the data follow a normal distribution. Briefly, these results indicate the goodness of fit for our model to the data and interpretation.

4.4. Granger Causality Test Results

Table 7 depicts the results from the pairwise Granger Causality test was applied to establish the direction of a causal relationship between entrepreneurship in terms of business formation (LNBF) and cost of business start-up procedures (LNCBSP), LNBF and unemployment (LNUNEMP), and LNCBSP and LNUNEMP.

As portrayed in

Table 7, there is no evidence of Granger causality between the variables, given the probability values all greater than 0.05 level of significance. Hence, the study failed to reject all the null hypotheses, signifying that the cost of business start-up procedures and business formation are independent of each other, just as much as business formation and unemployment, as well as unemployment and cost of business start-up procedures.

4.5. Discussions

The results of this study demonstrate that Namibia does not exhibit a long run relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship (business formation), which contradicts the findings of Cheratian et al. (2020) in Iran, where a long run (negative) nexus was observed between unemployment and entrepreneurial activity. As depicted in

Table 5, the short run estimation results show that entrepreneurship (business formation) increases with a rise in unemployment, which demonstrate the recession-push effect in the Namibian economy. Supported by these results are the findings of previous studies (Payne & Mervar, 2017; Ragmoun, 2023), which underscore the positive impact of unemployment on entrepreneurship from the global perspective. Besides that, our results also present evidence of the prosperity-pull effect given a reduction in unemployment due to an increase in entrepreneurship, although the effect is very minimal. These results agree with the findings from the global perspective (Camba, 2020; Fritsch & Wyrwich, 2017; Prasetyo, 2021; Stuetzer et al., 2018) where entrepreneurship emerged as remedy for unemployment. Furthermore, our results are also consistent with the findings of Galindo da Fonseca (2022), which indicates minimal effect of start-ups on job creation in Canada.

Overall, our results suggest that that the Namibian economy exhibits both the refugee and Schumpeter effects, conforming the ambiguity of nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship in other countries beyond the African boarders (Grigorescu et al., 2020; Halicioglu & Yolac, 2015; Padi & Musah, 2022). Similarly, the results are also consistent with the findings of Feki and Mnif (2019) which reveal the presence of both the refugee and Schumpeter effects in Tunisia. Finally, we have also discovered the impact of business start-up procedures on the relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship in Namibia. That is, the more unemployment increases, the more the procedures of starting businesses are eased. Thus, an increase in the number of individuals engaging in entrepreneurial activities, which, however, lead to the complexity of executing the formal processes of business start-ups.

Lastly, our Granger causality test results reveal that none of our variables Granger causes the other. This evidence naysays the findings Cheratian et al. (2020), which found a unidirectional short-run causal relationship from entrepreneurship to unemployment in some provinces in Iran and a unidirectional short-run causal relationship from unemployment to entrepreneurship in other provinces and a bidirectional causality between unemployment and entrepreneurship in the Unites States (Apergis & Payne, 2016).

4.6. Namibia’s Unemployment-Entrepreneurship Short-run Nexus Model

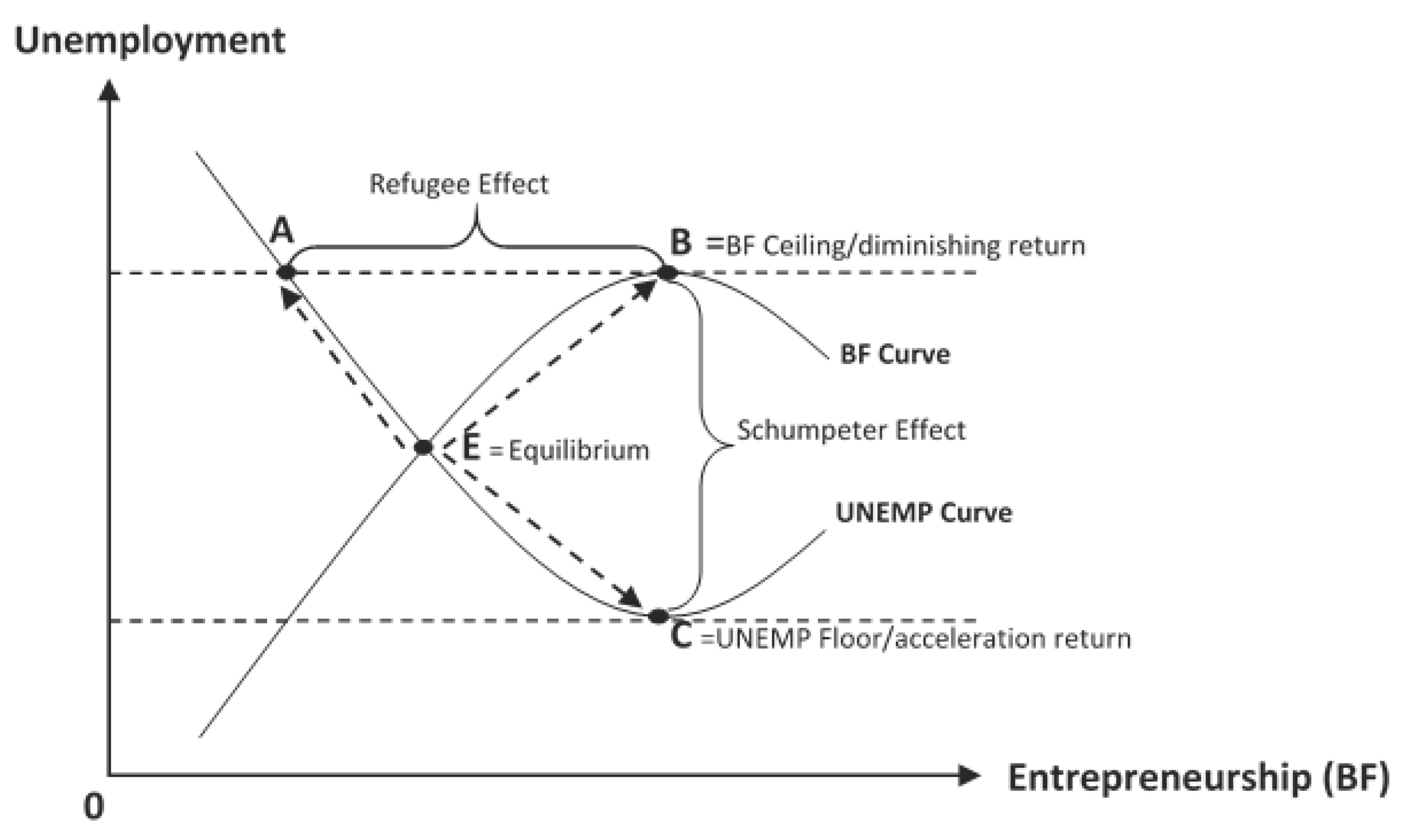

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment, where entrepreneurship is determined by the number of yearly business formations (BF) and unemployment is the annual unemployment rate. On the graph, unemployment is plotted on the vertical axis while entrepreneurship is on the horizontal axis, with point 0 indicating the origin. Moreover, equilibrium represents the intersection of entrepreneurship (BF) and unemployment (UNEMP) curves.

As depicted in

Figure 1, the equilibrium is a point that indicates the state where total unemployment equates to the total business formation in the economy. That is, entrepreneurial activities fully absorb the unemployment rate within a given period of time. As unemployment rises above the equilibrium, from point E to point A, unemployed people begin to venture into entrepreneurial activities. For that reason, new businesses start to penetrate the market and business formation increases above the equilibrium from point E to point B, which demonstrates the refugee effect (Cheratian et al., 2020; Emami-Langroodi, 2018; Prasetyo et al., 2022; Prasetyo & Kistanti, 2020; Tang, 2022). Due to an increase in business formation, unemployment reduces below the equilibrium level from point E to point C, which illustrates the Schumpeter effect (Aku-sika, 2020; Camba, 2020; Emami-Langroodi, 2018; Gautam & Lal, 2021; Grigorescu et al., 2020; Payne & Mervar, 2017; Prasetyo & Kistanti, 2020; Ragmoun, 2023). However, over time, the market gets saturated to the extent that business formation reaches the maximum point of acceleration and begins to diminish, as shown at point B, while unemployment keeps declining till it gets exhausted over time, where it starts to pick up as indicated at point C. Overall, the model demonstrates that the relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment is short-run in nature, where entrepreneurship can only address the issue of unemployment in the short-run.

5. Conclusions

This study intended to analyse the nexus between unemployment and entrepreneurship within the Namibian economy using several econometrical analyses. From the unit root test, all the variables were stationary at the first difference I(1), leading to a further cointegration analysis, which was measured using the Johansen-Juselius test to determine whether the variables are cointegrated in the long-run. Nevertheless, the Johansen-Juselius test did not find any cointegrating equation. Hence, we performed the Vector Autoregressive model to estimate the short run relationship between the variables. Following the VAR results, evidence indicates that each variable (business formation, cost of business start-up procedures, and unemployment) is strongly and positively endogenous, ceteris paribus. However, other weakly and positively endogenous and strongly exogenous impacts imply that an increase in the number of business formations makes the business start-up procedures more difficult, while unemployment puts more pressure on individuals to pursue entrepreneurship. Lastly, the study applied a pairwise Granger causality test to measure the direction of causality between the variables. The results indicate that business formation and cost of business start-up procedures, unemployment, and cost of business formation, as well as unemployment and cost of business start-up procedures, are independent of each other. Thus, all the null hypotheses of the Granger Causality test were rejected.

Based on these findings, the study recommends that policymakers should focus on other aspects beyond entrepreneurship when devising policies intended to address the issue of unemployment while not snubbing to ease the procedures of business start-ups to encourage entrepreneurial activities, which can address other macroeconomic issues beyond unemployment. However, the question of whether the businesses formed excel to make significant contributions to socio-economic welfare remains unanswered. Thus, the study suggests future research to delve deeper into the phenomenon regarding business outrival, given the contradiction of the simple theory of income choice that postulates that unemployed individuals possess inadequate endowments of human capital and entrepreneurial talent, which are required for business start-up and sustainability. Finally, the study also suggests future studies to use panel analysis between developing and developed countries to understand the matter from different stages of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.N, A.R.A and S.O.A., Formal analysis, J.P.N, Investigation, J.P.N, A.R.A; Methodology, J.P.N; Project administration, A.R.A; Resources, S.O.A; Software, J.P.N; Supervision, A.R.A; Validation; S.O.A; Visualization, A.R.A and S.O.A. Writing - original draft: J.P.N; Writing - review and editing A.R.A and S.O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC is funded by Walter Sisulu University, South Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aceytuno, M. T., Sánchez-López, C., & de Paz-Báñez, M. A. (2020). Rising inequality and entrepreneurship during economic downturn: An analysis of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in Spain. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12. [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z. J., Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Szerb, L. (2018). Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: an ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics, 51, 501–514. [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B. & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Aku-sika, B. (2020). Assessment of the Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth : A Ghanaian Case Study 2 Literature Review. 169–182.

- Alarifi, G., Robson, P., & Kromidha, E. (2019). The Manifestation of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Social Entrepreneurship Context. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 10, 307–327. [CrossRef]

- Amornbunchornvej, C., Zheleva, E., & Berger-Wolf, T. Y. (2019). Variable-lag granger causality for time series analysis. Proceedings - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics, DSAA 2019, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N., & Payne, J. E. (2016). An empirical note on entrepreneurship and unemployment: Further evidence from U.S. States. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 5, 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N., Content, J., Sanders, M., & Stam, E. (2018). Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Business Economics, 51, pp. 483-499. [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C. & Caudill, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship, institutions, and economic growth: Does the level of development matter? MPRA Paper No. 94244, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/94244/ (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Camba, A. L. (2020). Estimating the nature of relationship of entrepreneurship and business confidence on youth unemployment in the Philippines. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7, 533–542. [CrossRef]

- Cheratian, I., Golpe, A., Goltabar, S., & Iglesias, J. (2020). The unemployment-entrepreneurship nexus: new evidence from 30 Iranian provinces. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15, 469–489. [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1981). Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica, 49, 1057–1072. [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O. (2017). Determinants of Nordic entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24, 12–33. [CrossRef]

- Emami-Langroodi, F. (2018). SchumpeterrS Theory of Economic Development: A Study of the Creative Destruction and Entrepreneurship Effects on the Economic Growth. SSRN Electronic Journal, 4, 65–81. [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-Integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testin. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feki, C., & Mnif, S. (2019). Self-Employment and Unemployment in Tunisia: Application of the ARDL Approach. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9, 1200–1211. [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2017). The effect of entrepreneurship on economic development: An empirical analysis using regional entrepreneurship culture. Journal of Economic Geography, 17, 157–189. [CrossRef]

- Galindo da Fonseca, J. (2022). Unemployment, entrepreneurship and firm outcomes. Review of Economic Dynamics, 45, 322–338. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S., & Lal, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth: Evidence from G-20 Economies. Journal of East-West Business, 27, 140–159. [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A., Pîrciog, S., & Lincaru, C. (2020). Self-employment and unemployment relationship in Romania–Insights by age, education and gender. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja , 33, 2462–2487. [CrossRef]

- Halicioglu, F., & Yolac, S. (2015). Testing the Impact of Unemployment on Self-Employment: Evidence from OECD Countries. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Halid, H., Osman, S., & Abd Halim, S. N. J. (2020). Overcoming Unemployment Issues among Person with Disability (PWDs) through Social Entrepreneurship. Albukhary Social Business Journal, 1, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R. V., and Tanis, E. A. (2001). Probability and statistical inference (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Ivanovic-Djukic, M.; Lepojevic, V.; Stefanovic, S.; van Stel, A.; Petrovic, J. Contribution of entrepreneurship to economic growth: A comparative analysis of South East transition and developed European countries. International Review of Entrepreneurship 2018, 16, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Iwu, C. G., & Opute, A. P. (2019). Eradicating Poverty and Unemployment: Narratives of Survivalist Entrepreneurs. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8(December), 1438–1451. 1438. [CrossRef]

- Jarque, C.M.; Bera, A.K. A test for normality of observations and regression residuals. International Statistical Review 1987, 55, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S.; Juselius, K. Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with applications to the demand for money: Inference on cointegration. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2009, 52, 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y., & Xiong, W. (2021). Is entrepreneurship a remedy for Chinese university graduates’ unemployment under the massification of higher education? A case study of young entrepreneurs in Shenzhen. International Journal of Educational Development, 84(April), 102406. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J., & Capucho, J. (2021). Institutional, economic, and socio-economic determinants of the entrepreneurial activity of nations. Administrative Sciences, 11, 0–32. [CrossRef]

- Maritz, A., Perenyi, A., de Waal, G., & Buck, C. (2020). Entrepreneurship as the unsung hero during the current COVID-19 economic crisis: Australian perspectives. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12. [CrossRef]

- Miles, D. A. A taxonomy of research gaps: Identifying and defining the seven research gaps methodological gap. Journal of Research Methods and Strategies 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- National Planning Commission. (2017). Namibia’s 5. Namibia’s 5th National Development Plan (NDP5), 5, 7. Available online: https://www.npc.gov.na/national-plans-ndp-5/?wpfb_dl=298.

- Namibia Statistics Agency (2023). Namibia youth unemployment rate 2023. Available online: https://nsa.org.na/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Nautwima, J. P., & Asa, A. R. (2022). The impact of microfinance support on the development of manufacturing SMEs operating in Windhoek, Namibia. Archives of Business Research, 9, 250–272. [CrossRef]

- Nautwima, J. P., & Asa, A. R. (2021). The relationship between inflation and unemployment in Namibia Within the Framework of the Phillips Curve. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 7, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.R.; Plosser, C.I. Trends and random walks in macroeconomic time series: Some evidence and implication. J. Monet. Econ. 1982, 10, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padi, A., & Musah, A. (2022). Entrepreneurship as a potential solution to high unemployment: A systematic review of growing research and lessons for Ghana. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, 5, 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. E., & Mervar, A. (2017). The entrepreneurship-unemployment nexus in Croatia. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 6, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, J., Malec, K., Majune, S. K., Appiah-Kubi, S. N. K., Maitah, M., Maitah, K., Gebeltová, Z., & Abdullahi, K. T. (2020). Agriculture as a determinant of Zambian economic sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, P. E. The Role of MSME on Unemployment in Indonesia. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education 2021, 12, 2519–2525. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo, P. E., & Kistanti, N. R. (2020). Role of Social Entrepreneurship in Supporting Business Opportunities and Entrepreneurship Competitiveness. Open Journal of Business and Management, 08, 1412–1425. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, P. E., Setyadharma, A., & Kistanti, N. R. (2022). The role of institutional potential and social entrepreneurship as the main drivers of business opportunity and competitiveness. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10, 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Ragmoun, W. (2023). Institutional quality, unemployment, economic growth and entrepreneurial activity in developed countries: a dynamic and sustainable approach. Review of International Business and Strategy, 33, 345–370. [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, G., Lai, Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2017). Exploring the relationship between HRM and firm performance: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Human Resource Management Review, 27, 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, A., Saikia, B., & Tripathi, D. (2021). Can unemployment be answered by Micro Small and Medium Enterprises? Evidences from Assam. Indian Growth and Development Review, 14, 199–222. [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, F., & Aritenang, A. F. (2019). The impact of fiscal decentralization on economic performance in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 340, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Stuetzer, M., Audretsch, D. B., Obschonka, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Potter, J. (2018). Entrepreneurship culture, knowledge spillovers and the growth of regions. Regional Studies, 52, 608–618. [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals. (2019). The sustainable development goals report 2019. United Nations Publication Issued by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 64.

- Tang, Y. (2022). The effect of social capital on the career choice of entrepreneurship or employment in a closed ecosystem. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Voskoboynikov, I. (2023). Economic Growth. The Contemporary Russian Economy: A Comprehensive Analysis, 8, 291–312. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. (2004). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (2nd ed.).; SouthWestern College Pub: Cincinnati, OH, USA.

- You, Y.; Zhu, F.; Ding, X. College student entrepreneurship in China: Results from a national survey of directors of career services in Chinese higher education institutions. Current Issues Compar. Educ. 2017, 19, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).