Submitted:

16 August 2023

Posted:

18 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental samples

2.2. Experimental methods

- Monitoring the thermal degradation of samples based on gradual heating of the sample by radiant heat and tracking degradation points with identification of temperature and time during the degradation processes.

- Determination of the minimum ignition temperature using isothermal testing using a hot-plate according to EN 50281-2-1:1998 [26].

2.2.1. Methodology for monitoring the thermal degradation of hay and straw

2.2.2. Determination of the minimum ignition temperature by isothermal heating using a hot-plate according to EN 50281-2-1:1998 [26]

- Glowing, smouldering, or flaming combustion,

- The temperature-time curve recorded by the thermocouple, which is placed at the centre of the sample layer, continuously rises with comparison to the temperature of the isothermally heated plate,

- The temperature measured in the sample layer is 250°C higher than the temperature of the heated plate.

3. Results and Discussion

| Ignition temperature | Hay | Straw |

|---|---|---|

| Experimentally determined temperature (°C) | 406.6±5.1 | 385.33±13.2 |

| Temperature experimentally determined according to EN 50281-2-1:1998 [26] (°C) | 407 | 380 |

| Temperature according by [18] | 310 | 330 |

| Temperature according to [29] | 230 | 310 |

4. Conclusions

- The minimum ignition temperature of hay according to EN 50281-2-1:1998 [26] is 407°C.

- During exposure to radiant heat, the critical temperatures of hay and straw were comparable, except for the initial phase, where hay degradation started earlier at a lower temperature and in a shorter time interval compared to straw.

- It is not possible to unequivocally determine which of the mentioned materials poses a greater risk of fire.

- The significant effect of weight and sample type on the minimum ignition temperature of hay and straw, as well as on the time-related development of thermal degradation of the samples, was not confirmed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Čajová, K. N.; Holubčík, M.; Trnka, J.; Čaja, A. Analysis of Ash Melting Temperatures of Agricultural Pellets Detected during Different Conditions. Fire 2023, 6, 88. [CrossRef]

- Štulajter, M., Lieskovský, M., Messingerová, V. Energy properties of pellets, briquettes and charcoal produced in Slovakia. Acta Facultatis Forestalis 2015, 57, 133-144. (in Slovak).

- Martiník, L.; Drastichová, V.; Horák, J.; Jankovská, Z.; Krpec, K.; Kubesa, P.; Hopan, F.; Kaličáková, Z. Combustion of waste biomass in small facilities. Chemické listy. 2014,108, 156-162. (in Czech).

- Mullerová, J.; Hloch, S.; Valíček, J. Reducing Emissions from the Incineration of Biomass in the Boiler. Chemické listy 2010, 104, 9.

- Baláš, M.; Lisý, M.; Lisá, H.; Vavříková, P., Milcháček, P.; Elbl, P. Spalné teplo a složení biopaliv a bioodpadů. Energie z biomasy XX. Vysoké učení technické, Fakulta strojního inženýrství, Lednice, 17th-19th September 2019. Available online: https://eu.fme.vutbr.cz/file/Sbornik-EnBio/2019/Sborn%C3%ADk_Enbio_2019.pdf (accessed on 04 August 2023). (in Czech).

- Daňková, D.D.; Hejhálek, J. Tepelné izolácie – prehľad, materiály, druhy, spôsoby použitia. https://www.istavebnictvo.sk/clanky/tepelne-izolace-prehled-materialy-druhy-zpusoby-po (accessed on 04 December 2009). (in Slovak).

- Tobias, R., Writer, R. Building With Straw Bales: A Comprehensive Guide. Available online: https://www.buildwithrise.com/stories/how-to-build-a-home-using-straw-bale (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Cascone, S.; Rapisarda, R., Cascone, D. Physical Properties of Straw Bales as a Construction. Material: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3388. [CrossRef]

- Giertlová, Z. Rettung von Großvieh bei Brandereignissen landwirtschaftlicher Gebäude in Holzbauweise. TV3: Brandschutztechnische Maßnahmen: Zwischenbericht, Berichtzeitraum 1.4.2021-30.6.2022, Förderkennzeichen 2220HV008C. Final Report. Bearbeitung Präventionsingenieure e:V., Planegg, 2023. (not publish).

- Marková, I.; Giertlová, Z.; Hutár, M. Stanovenie teploty vznietenia sena pre účely posudzovania rizík v stredných a malých poľnohospodárskych podnikoch. Krízový manažment 2022, 21,50-56. (in Slovak).

- Kováč, M.; Čupka, V.; Kacerovský, O. Výživa a kŕmenie hospodárskych zvierat (Nutrition and feeding of farm animals). 1st ed.; Publisher: Príroda, Bratislava, Slovak Republic, 1989, 536 pp. (in Slovak).

- Sraková, E.; Suchý, P.; Herzig, I.; Suchý, P.; Tvrzník, P. 2008. Výživa a dietetika. I. diel –všeobecná výživa (Nutrition and dietetics. Part I – general nutrition). 1st ed.; Publisher: VFU, Brno, Czech Republic, 2008. pp. 75-76. (in Czech).

- Zarechny M.V. Koľko sena potrebuje krava na rok, deň a zimu (How much hay does a cow need for a year, day and winter). Available online: https://garden.desigusxpro.com/sk/krs/soderzhani/skolko-sena-na-zimu-nuzhno.html (accessed on 10 July 2023). (in Slovak).

- Gaspercova, S.; Osvaldova, LM.; Kadlicova, P. Additional thermal insulation materials and their reaction on fire. Journal FIRE PROTECTION, SAFETY AND SECURITY 2017, 51-56.

- Osvaldova, LM.; Janigova, I.; Rychly, J. Non-Isothermal Thermogravimetry of Selected Tropical Woods and Their Degradation under Fire Using Cone Calorimetry. Polymers 2021, 13, 708. [CrossRef]

- Marková, I.; Mitrenga, P.; Makovická Osvaldová, L.; Hybská, H. Determination of the ignition temperature of hay for the purposes of fire risk assessment on farms - Slovak case study. BioResources 2022, 17, 6926-6940. [CrossRef]

- BORGA. Skladovanie sena a slamy alebo ako predísť požiarom. Available online: https://www.montovane-haly-borga.sk/skladovanie-sena-a-slamy-alebo-ako-predist-poziarom (accessed on 30 May 2022). (in Slovak).

- Preventing fires in baled hay and straw. Farm and Ranch eXtension in Safety and Health (FReSH) Community of Practice 2012. Available online: http://www.extension.org/pages/66577/preventing-fires-in-baled-hay-and-straw4 (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Fire Hazard in Wet Bales. Available online: https://extension.sdstate.edu/fire-hazard-wet-bales (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Decree of the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic No. 258/2007 Coll. on requirements for fire safety in storage, storage and handling of solid combustible substances.

- Ďudák, J. Stavby a objekty na uskladnenie objemových krmív (Buildings and objects for bulk feed storage). Available online: http://www.agroparadenstvo.sk/stroje-zber-urody?article=2450 (accessed 20 Januay 2022). (in Slovak).

- Tables of Flammable and Dangerous Substances. 1st ed. Publisher: Svaz PO ČSSR, Prague, 1980 (in Czech).

- Kadlicová, P.; Makovická Osvaldová, L.; Gašpercová, S. Ekologické dopady zatepľovacích systémov (Environmental impact of thermal isulation materials). Acta Universitatis Matthiae Belii, seria Environmentálne manažérstvo 2016, 18, 2. (in Slovak).

- Makovická Osvaldová, L.; Gašpercová, S.; Petho, M. Natural Fiber Thermal Insulation Materials from Fire Prevention Point of View. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Material, Energy and Environment Engineering, November, Bratislava, Slovak Republic, 5th May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic 2022. STATdat. Štatistika stavu hospodárskych zvierat za jednotlivé roky 2011- 2020. Available online: http://statdat.statistics.sk/cognosext/cgi-bin/cognos.cgi?b_action=cognosViewer&ui.action=run&ui.object=storeID(%22iF60EC5BD94894A19A9737BA5A8E4F162%22)&ui.name=Stavy%20hospod%c3%a1rskych%20zvierat%20k%2031.12.%20%5bpl2016rs%5d&run.outputFormat=&run.prompt=true&cv.header=false&ui.backURL=%2fcognosext%2fcps4%2fportlets%2fcommon%2fclose.html (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- EN 50281-2-1 (1998) Electrical apparatus for use in the presence of combustible dust - Part 2-1: Test methods - Methods for determining the minimum ignition temperatures of dust.

- Balog, K.; Martinka, J.; Chrebet, T.; Hrušovský, I., Hirle, S. Zápalnosť materiálov a forenzný prístup pri zisťovaní príčin požiarov (Flammability of materials and forensic approach in fire investigation). In Proceedings of XXIII. International scientific conference ExFoS - Expert Forensic Science, Brno, Czech Republic, 2nd May 2014, 20-36. (in Slovak).

- Hay and Straw Barn Fires a Real Danger. Available online: https://agcrops.osu.edu/newsletter/corn-newsletter/2019-21/hay-and-straw-barn-fires-real-danger (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Flachbart, J.; Svetlík, J. Waste materials – sources of fire. Fire risk management in the natural environment. Collection of scientific papers. Published by: Fire Engineering and Expertise Institute of the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic, Bratislava, Slovak Republic, 2018, 101-108. (in Slovak).

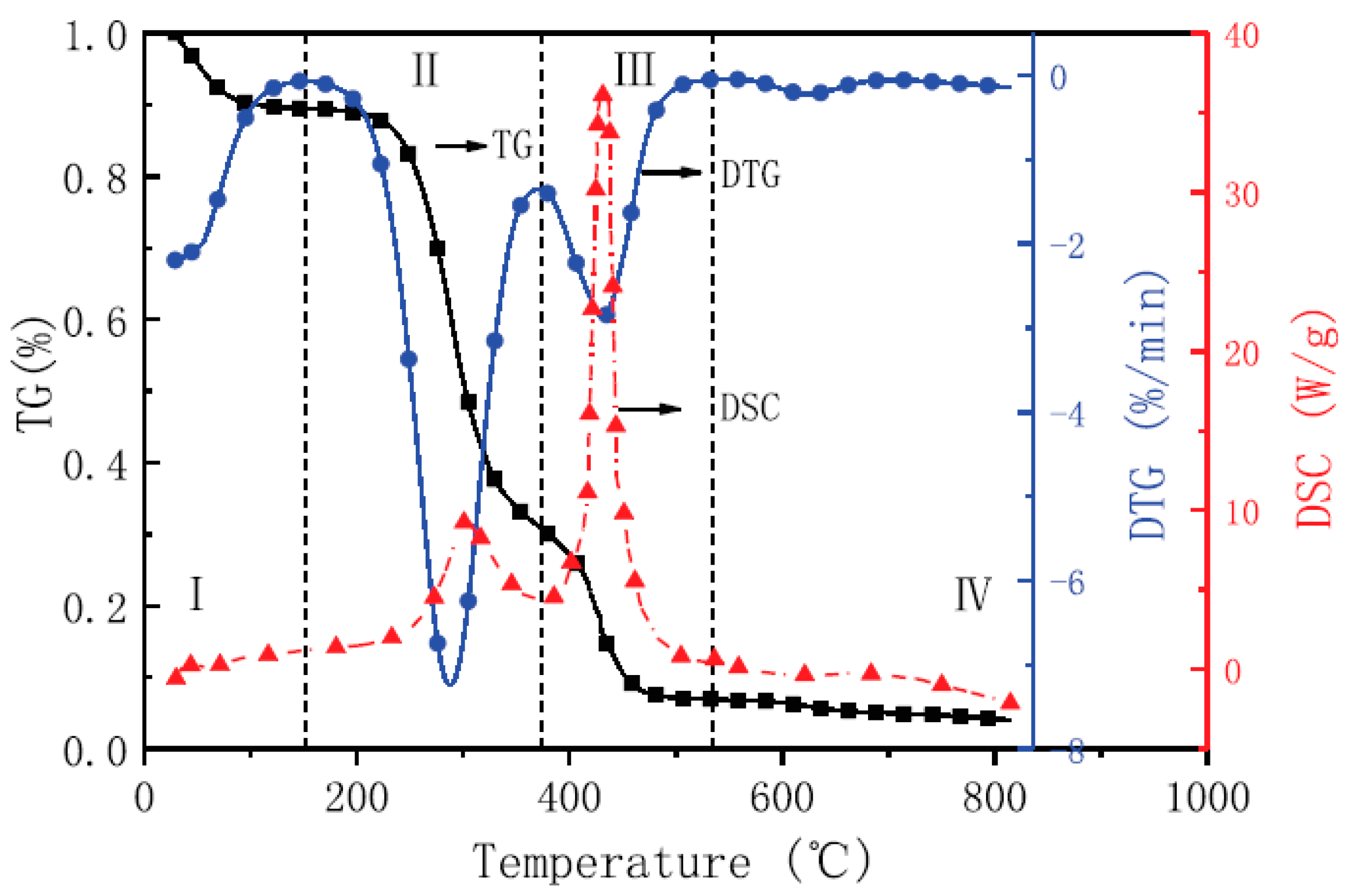

- Xie, T.; Wei, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Comparative analysis of thermal oxidative decomposition and fire characteristics for different straw powders via thermogravimetry and cone calorimetry. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, 134, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.11.028.

| Solid flammable substance | Characteristics | Moisture | Storage [17]. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dried animal feed (silage) | Mown green grasses | more than 16% and up to 30% | |

| Mown green legumes | more than 16% and up to 35% | ||

| Hay | Dried stem of grasses or legumes | Up to 16 % | Bales, Haystack, Hay loft, Barn, Hay shed |

| Straw | Dried stalk of cereal crops | - |

| Samples (Fodder) | Hay | Straw |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) determined gravimetrically | 11 | 10 |

| Moisture (%) according to 258/2007 Act No. [20] | 9-10 | 10 |

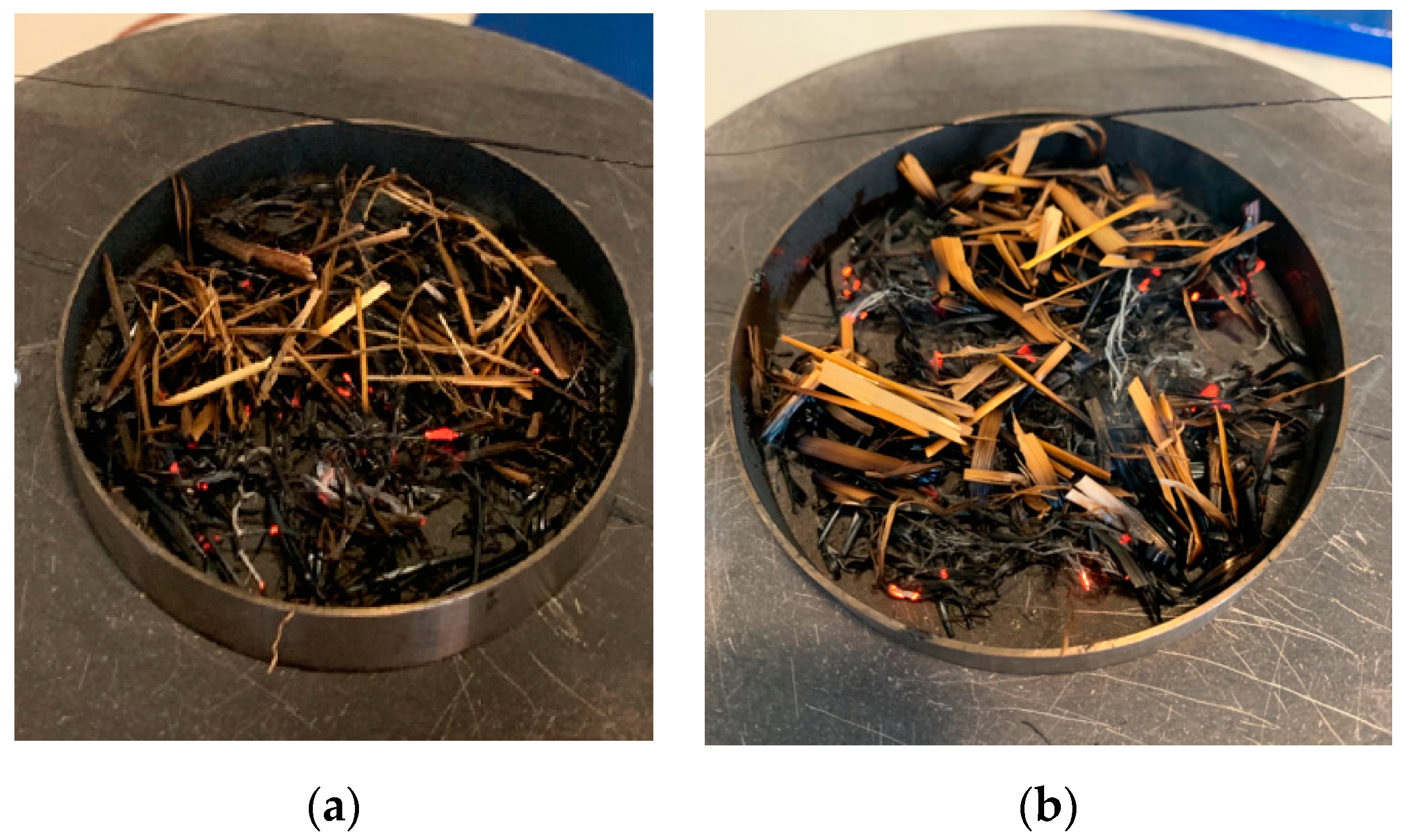

| Sample before the experiment |  |

|

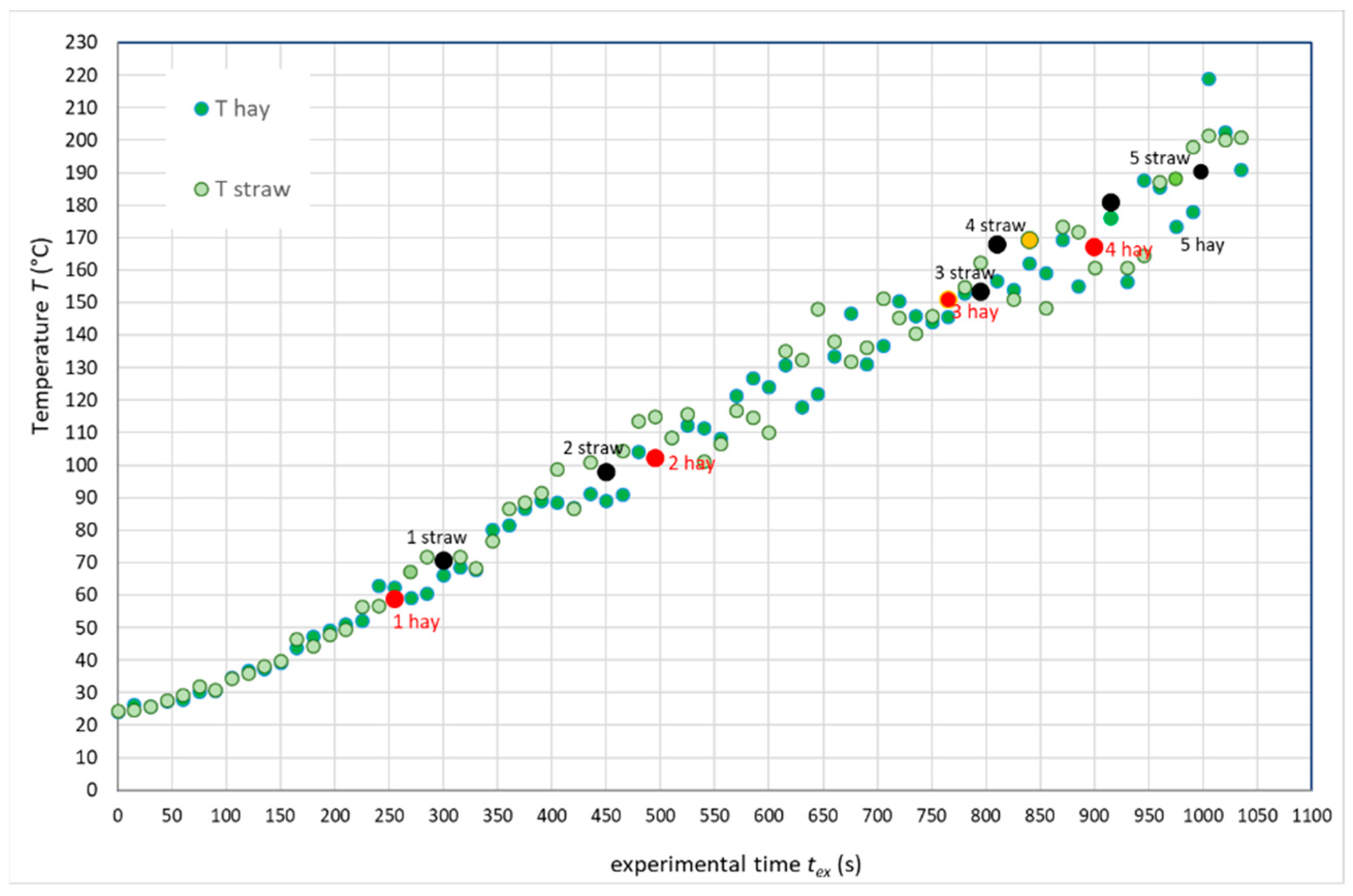

| Straw | ||||

| Process order | Tstraw (°C) | tex(min)/(s) * | Visual observations during measurement | Tigniton °C |

| 1. | 69.1 | 6 (360s) | Odour noted | 385.33±13.2 |

| 2. | 91.4 | 8.5 (525s) | Smoking process appeared | |

| 3. | 142.6 | 11 (825s) | Carbonization of the lower stems of the tested sample | |

| 4. | 145.2 | 16 (975s) | Carbonization of the edges of the tested sample, increasing smoke intensity | |

| 5. | 173.2 | 17.5 (1050s) | Ignition and formation of flames | |

1.  2. 2.  3. 3.  4. 4.  5. 5.

| ||||

| Hay | ||||

| Process order | Thay (°C) | tex(min)/(s) * | Visual observations during measurement | Tigniton °C |

| 1. | 111.3 | 8 (480 s) | Smoke, thermal degradation | 406.6±5.1 |

| 2. | 160.8 | 13.5 (810 s) | Carbonization of the layer on the surface of the hot-plate | |

| 3. | 185.4 | 16.75 (1005s) | Carbonization of the edges of the samples and gradual degradation of the entire surface, smouldering process observed | |

| 4. | 192.6 | 18 (1080 s) | Ignition occurs | |

2.  3. 3.  4. 4.

| ||||

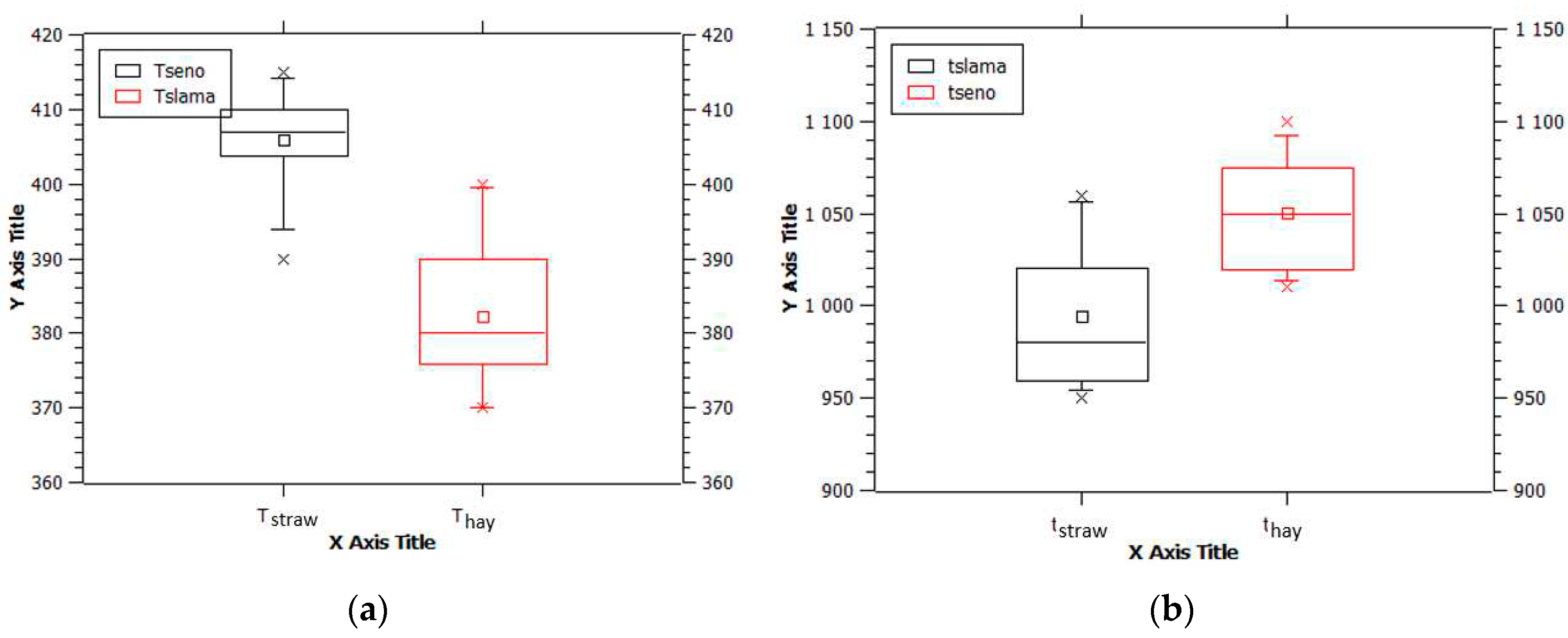

| Samples | Hay | Straw | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitored parameters | Thot (°C) | Thay (°C) | tex (s) | Thot (°C) | Tstraw (°C) | tex (s) |

| 1. process: Odour | - | 62.1±5.1 | - | 110-160 | 68.9±1.1 | 305±43.0 |

| 2. process: Smoke | 220-280 | 105.9±5.2 | 505±69.9 | 160-200 | 97-5±5.8 | 454±61.5 |

| 3. process: Carbonization of the bottom layer of the sample | 340-360 | 150.2±7.6 | 765±44.1 | 360-400 | 169.4±19.27 | 800±18.7 |

| 4. process: Carbonization of the edges of the sample | 400-430 | 175.6±6.9 | 905±50.1 | 400-410 | 179.4±27.5 | 815±30.8 |

| 5. process: Ignition and burning |

430-450 | 183.8±9.2 | 1050±24.5 | 410-430 | 189.9±25.6 | 960±63.6 |

| Ignition temperature | 406.6±5.1 | 385.33±13.2 | ||||

| Ignition temperature according to EN 50281-2-1:1998 [26]. | 407 | 380 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).