Submitted:

17 August 2023

Posted:

18 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Socioeconomic Aspects of Wildlife Valorisation in Madagascar

1.2. Wildlife Tourism Revenue

1.3. Flora and Fauna trade Revenues

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

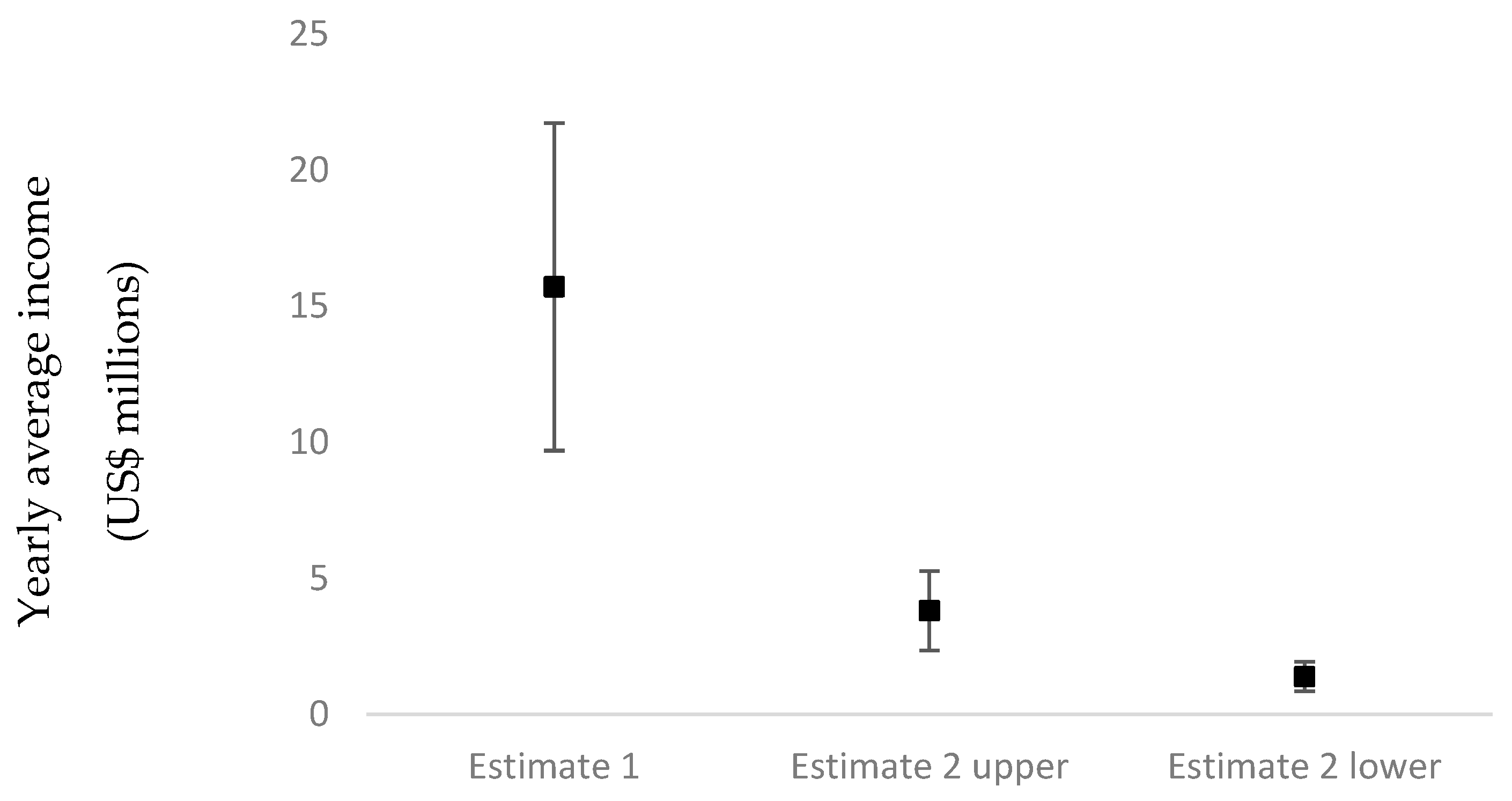

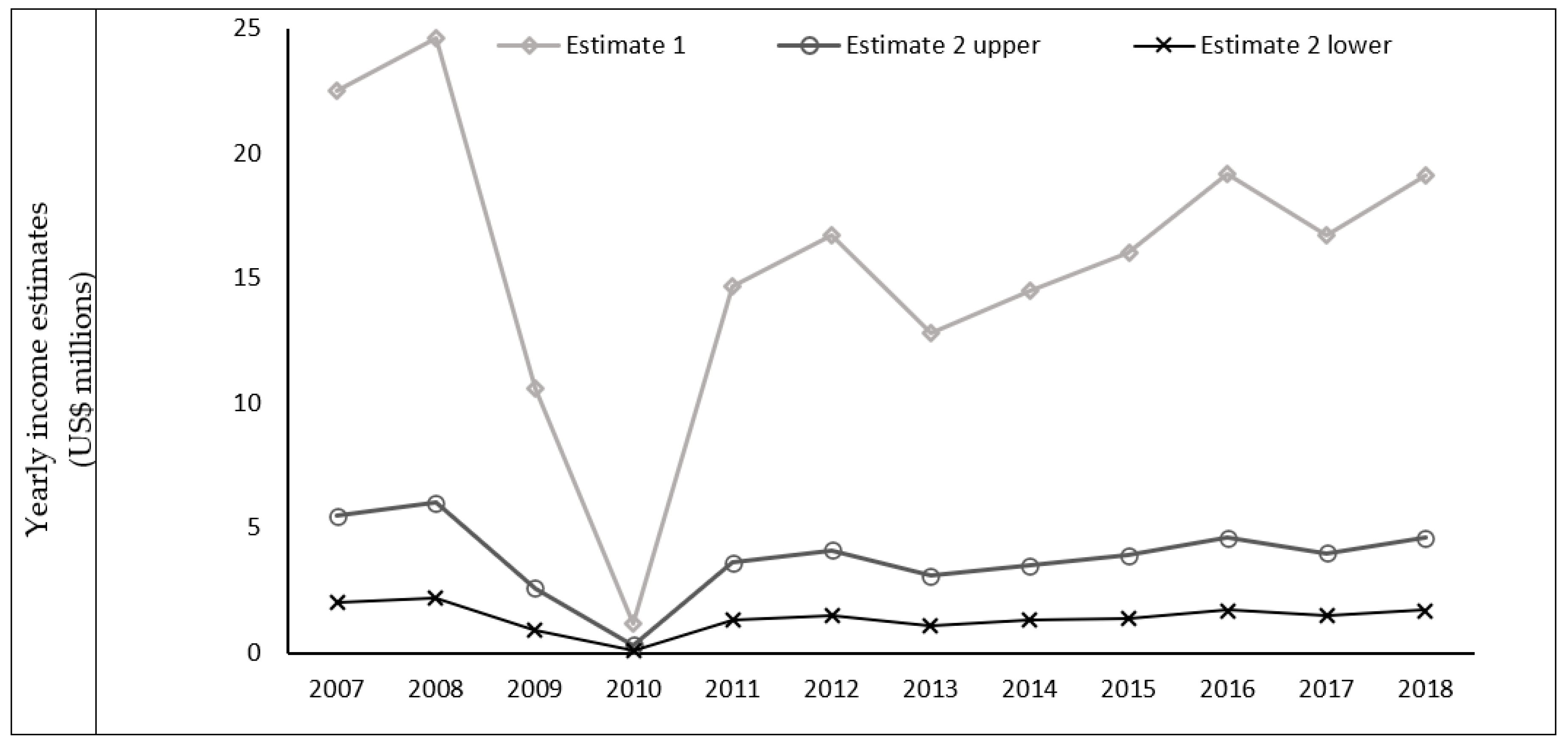

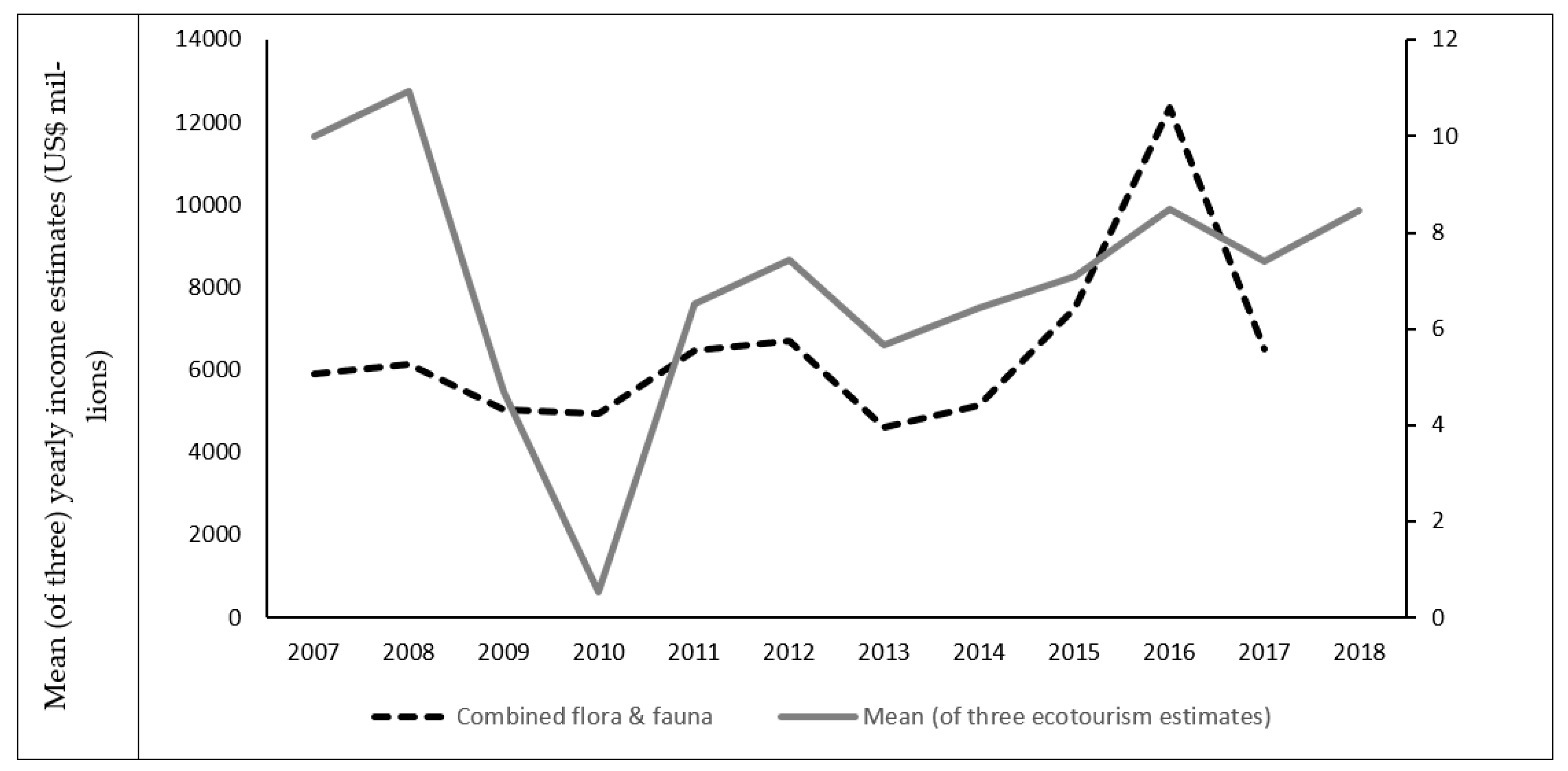

3.1. Ecotourism Revenue Generation

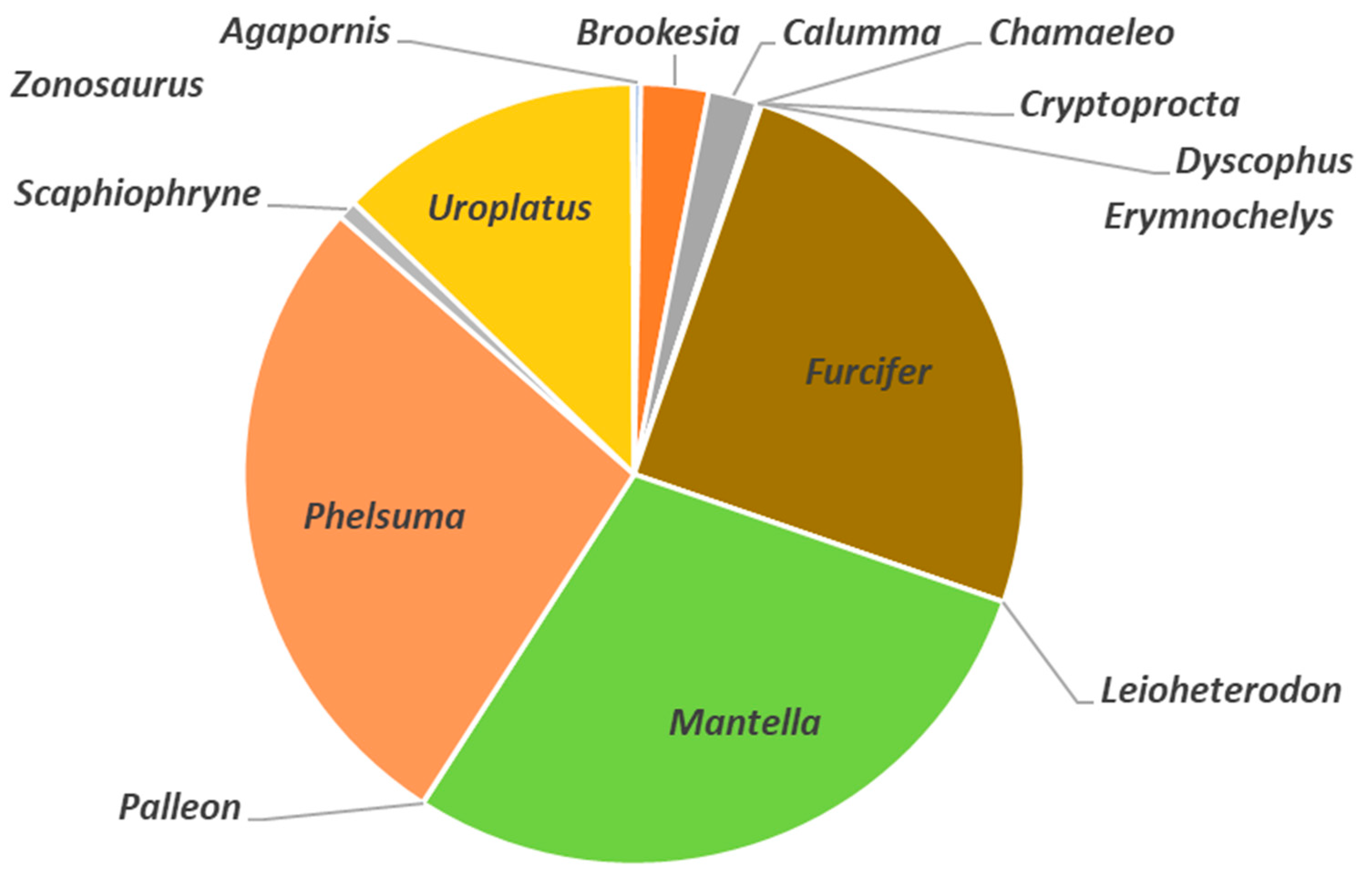

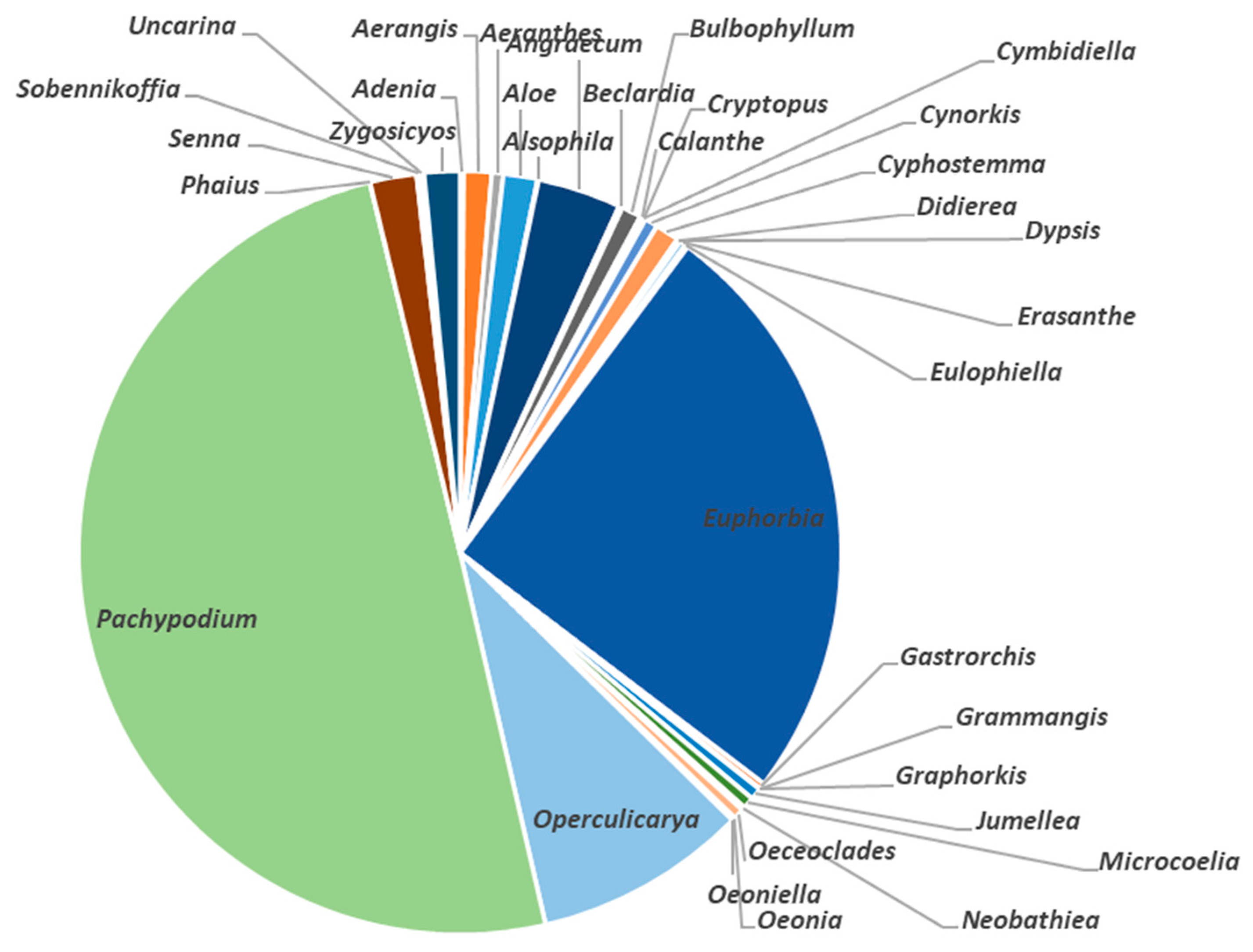

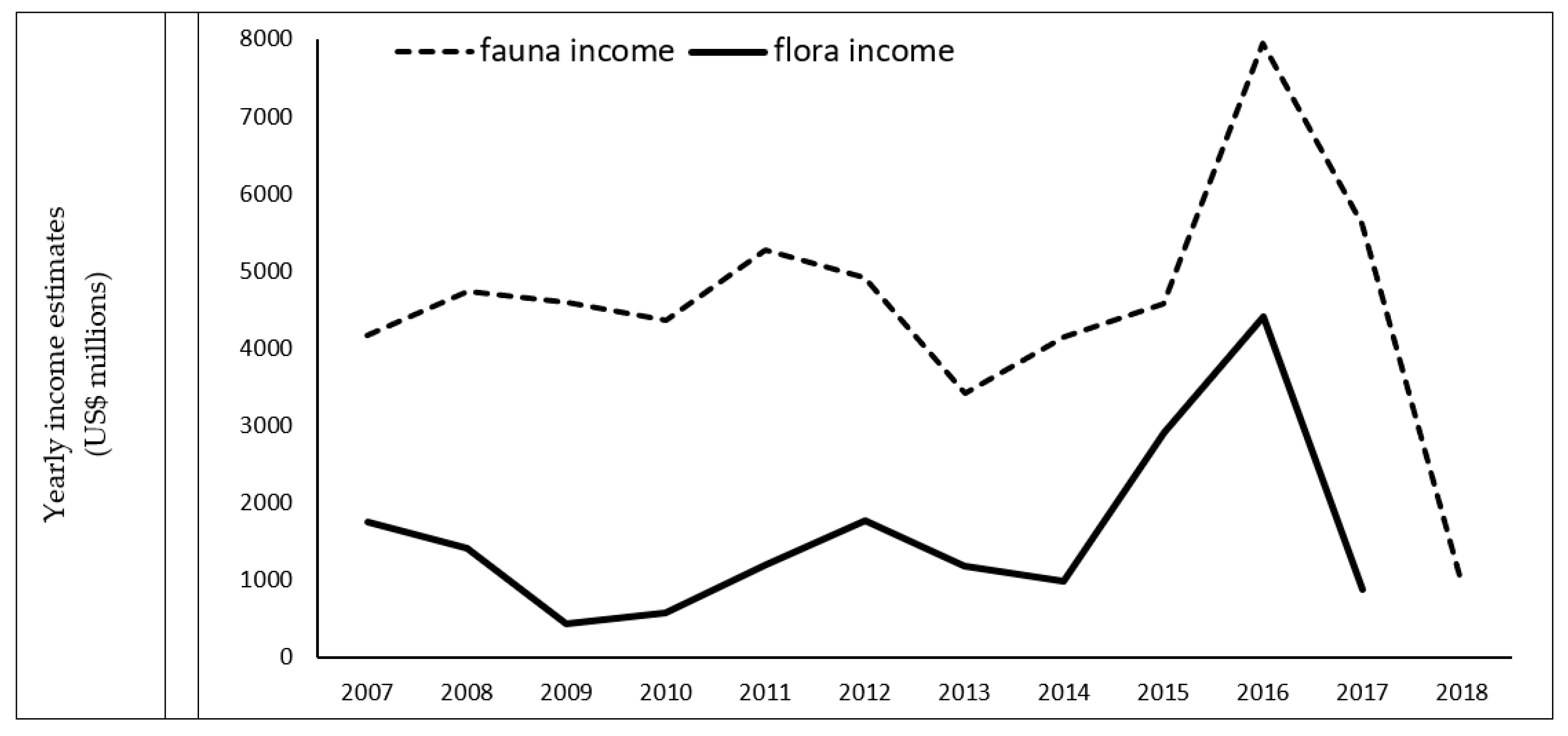

3.2. Flora and Fauna trade Revenues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPBES. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the 733 Intergovernmental Science- Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 2019.

- Low, B.R.; Costanza, E.; Ostrom, J.; Wilson, S.C. Human-ecosystem interactions: a dynamic integrated model. Ecological economics 1999, 31, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner-Gulland, E.; Mace, R. Conservation of Biological Resources; Blackwell Science: Oxford, London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. Participatory biodiversity conservation rethinking the strategy in the low potential areas of tropical Africa. Natural Resource Perspectives 1998, London, Overseas. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.; McGuire, S.; Sullivan, S. Global environmental justice and biodiversity conservation. The Geographical Journal 2013, 179, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Environmental justice: concepts, evidence and politics. Routledge, London, UK, 2012.

- Chan, K.; Satterfield, T. Justice, equity and biodiversity. In The encyclopedia of biodiversity. Levin, S., Daily, G. C., Colwell, R. K., Eds. Elsevier, Oxford, UK 2007, pp.1-9.

- Casse, T.; Milhøj, A.; Ranaivoson, S.; Randriamanarivo, J. R. Causes of deforestation in southwestern Madagascar: what do we know? Forest Policy and Economics 2004, 6, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, C.D.; Bonds, M.H.; Brashares, J.S.; Rasolofoniaina, B. J. R.; Kremen, C. Economic Valuation of Subsistence Harvest of Wildlife in Madagascar. Conservation Biology 2014, 28, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, D. Man and tegu lizards in eastern Paraguay. Biological Conservation 1987, 41, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Pascual, U. IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Christie, M., Baptiste, B., González-Jiménez, D., Anderson, C.B., Athayde, S., Barton, D.N., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Jacobs, S., Kelemen, E., Kumar, R., Lazos, E., Martin, A., Mwampamba, T.H., Nakangu, B., O’Farrell, P., Raymond, C.M., Subramanian, S.M., Termansen, M., Van Noordwijk, M., Vatn, A. Eds. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.W.; Scott, D.E.; Ryan, T.J.; Buhlmann, K.A.; Tuberville, T.D.; Metts, B.S.; Greene, J.L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. The Global Decline of Reptiles, Déjà Vu Amphibians. BioScience 2000, 50, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, K.E.; LaFleur, M.; Clarke, T.A. Illegal lemur trade grows in Madagascar. Nature 2017, 541, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, E. R. Logging of rare Rosewood and Palisander (Dalbergia spp.) within Marojejy National Park, Madagascar. Madagascar conservation and development 2007, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.K.B.; Tognelli, M.F.; Bowles, P.; Cox, N.; Brown, J.L.; Chan, L.; Andreone, F.; Andriamazava, A.; Andriantsimanarilafy, R.R.; Anjeriniaina, M.; Bora, P.; Brady, L.; Hantalalaina, E.F.; Glaw, F.; Griffiths, R.A.; Hilton-Taylor, G.; Hoffmann, M.; Katariya1, V.; Rabibisoa, N.H.; Rafanomezantsoa, J.; Rakotomalala, D.; Rakotondravony, H.; Rakotondrazafy, N.A.; Ralambonirainy, J.; Ramanamanjato, J.-B.; Randriamahazo, H.; Randrianantoandro, J.C.; Randrianasolo, H.H.; Randrianirina, J.E.; Randrianizahana, H.; Raselimanana, A.P.; Rasolohery, A.; Ratsoavina, F.M.; Raxworthy, C.; Robsomanitrandrasana, E.; Rollande, F.; van Dijk, P.P.; Yoder, A.D.; Vences, M. Extinction Risks and the Conservation of Madagascar’s Reptiles. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaw, F.; Vences, M. Current counts of species diversity and endemism of Malagasy amphibians and reptiles. In Diversité et Endémisme à Madagascar, Lourenço, W. R.; Goodman, S. M. Eds. Mémoires de la Société de Biogéographie, Paris 2000, pp. 243–248.

- Vieites, D.R.; Wollenberg, K.C.; Andreone, F.; Köhler, J.; Glaw, F.; Vences, M. Vast underestimation of Madagascar’s biodiversity evidenced by an integrative amphibian inventory. PNAS 2009, 106, 8267–8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S. M. (Ed.) The New Natural History of Madagascar. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA, 2022.

- Rabesahala Horning, N. Madagascar’s biodiversity conservation challenge: from local- to national-level dynamics. Environmental Sciences 2008, 5, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J. The local costs of establishing protected areas in low-income nations: Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar. Ecological Economics 2002, 43, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamsundar, P.; Kramer, R. Biodiversity conservation – at what cost? A study of households in the vicinity of Madagascar’s Mantadia National Park. Ambio 1997, 26, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll, M.E.; Langrand, O. Madagascar: revue de la conservation et des aires protégées. WWF, Gland, Switzerland, 1989.

- Durbin, J.; Ralambo, J.A. The role of local people in the successful maintenance of protected areas in Madagascar. Environmental Conservation 1994, 21, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C. J.; Nicoll, M. E.; Mbohoahy, T.; Oleson, K. L. L.; Ratsifandrihamanana, A. N.; Ratsirarson, J.; de Roland, L.-A. R.; Virah-Sawmy, M.; Zafindrasilivonona, B.; Davies, Z. G. Protected areas for conservation and poverty alleviation: experiences from Madagascar. Journal of Applied Ecology 2013, 50, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, A.; Ramarolahy, A. A.; Jones, J.P.G.; Milner-Gulland, E. J. ; Evidence for the effects of environmental engagement and education on knowledge of wildlife laws in Madagascar. Conservation Letters 2011, 4, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.A.; Pagiola, S. Ecotourism: Incentives for conservation success. Environment department, World Bank, 2001.

- Buckley, R. Conservation tourism. CABI, Cambridge, USA, 2010.

- Ormsby, A.; Mannle, K. Ecotourism benefits and the role of local guides at Masoala National Park, Madagascar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2006, 14, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neudert, R.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Wathold, F. Global benefits and local costs – The dilemma of tropical forest conservation: A review of the situation in Madagascar. Environmental Conservation 2017, 44, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. Towards a wider adoption of environmental responsibility in the hotel sector. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 2007, 8, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, J. R.; Ring-tailed lemurs threatened by illegal pet trade. Scientific American 2015. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/extinction-countdown/ring-tailed-lemurs-pet-trade/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Moorhouse, T.P.; Dahlsjö, C.A.; Baker, S.E.; D’Cruze, N.C.; Macdonald, D.W. The customer isn’t always right— conservation and animal welfare implications of the increasing demand for wildlife tourism. PloS One 2015, 10, e0138939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorhouse, T.; D’Cruze, N. C.; Macdonald, D. W. Unethical use of wildlife in tourism: What’s the problem, who is responsible, and what can be done? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2017, 25, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J. Sharing national park entrance fees: Forging new partnerships in Madagascar. Society & Natural Resources 1998, 11, 517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberg, K.C.; Jenkins, R.K.; Randrianavelona, R.; Rampilamanana, R.; Ralisata, M.; Ramanandraibe, A.; Ravoahangimalala, O.R.; Vences, M. On the shoulders of lemurs: pinpointing the ecotouristic potential of Madagascar’s unique herpetofauna. Journal of Ecotourism 2011, 10, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, L.D.; Griffiths, R.A. Status Assessment of Chameleons in Madagascar. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN, Cambridge, UK, 1999.

- Robinson, J.E.; Fraser, I. M.; St. John, F.A.V.; Randrianantoandro, J. C.; Andriantsimanarilafy, R. R.; Razafimanahaka, J. H.; Griffiths, R.A.; Roberts, D.L. Wildlife supply chains in Madagascar from local collection to global export. Biological Conservation 2018, 226, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzhorn, J.; Manjoazy, T.; Paplow, O.; Randrianavelona, R.; Razafimanahaka, J.; Ronto, W.; Walker, R. Rights to trade for species conservation: Exploring the issue of the radiated tortoise in Madagascar. Environmental Conservation 2015, 42, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P. O.; Wilmé, L. Madagascar rich and intransparent. Madagascar conservation and development 2013, 8, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Chng, S. Rising internet-based trade in the Critically Endangered ploughshare tortoise Astrochelys yniphora in Indonesia highlights need for improved enforcement of CITES. Oryx 2018, 52, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J. L. Madagascar rosewood, illegal logging and the tropical timber trade. Madagascar Conservation & Development 2010, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rabemananjara, F. C. E.; Raminosoa, N. R.; Ramilijaona, O. R.; Rakotondravony, D.; Andreone, F.; Bora, P.; Carpenter, A. I.; Glaw, F.; Razafindrabe, T.; Vallan, D.; Vieites, D. R.; Vences, M. Malagasy poison frogs in the pet trade: a survey of levels of exploitation of species in the genus Mantella. In Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar proceedings, Andreone, F. Ed. Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Natural di Torino 2008, pp.277-300.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Robson, O. Madagascan amphibians as a wildlife resource and their potential as a conservation tool: species and numbers exported, revenue generation and bio-economic models to explore conservation benefits. In Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar proceedings, Andreone, F. Ed. Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Natural di Torino 2008, pp.357-376.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Rowcliffe, M.; Watkinson, A.R. The dynamics of the global trade in chameleons. Biological Conservation 2004, 120, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.I.; Andreone, F.; Moore, R.D.; Griffiths, R.A. A review of the global trade in amphibians: The types of trade, levels and dynamics in CITES listed species. Oryx 2014, 48, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.I. The ecology and exploitation of chameleons in Madagascar. PhD thesis, University of East Anglia, UK, 2003.

- Carpenter, A.I.; Robson, O.; Rowcliffe, M.; Watkinson, A.R. The impacts of international and national governance on a traded resource: A case study of Madagascar and its chameleon trade. Biological Conservation 2005, 123, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreone, F.; Carpenter, A.I.; Cox, N.; du Preez, L.; Freeman, K.; Furrer, S.; Carcia, G.; Glaw, F.; Glos, J.; Kohler, J.; Mendelson, J.R.; Mercurio, V.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Moore, R.D.; Rabibisoa, N.H.C.; Randriamahazo, H.; Randrianasolo, H.; Raminosoa, N.R.; Ramilijaona, O.R.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Vallan, D.; Vence, M.; Vieites, D.R.; Wheldon, C. The challenge of conserving amphibian megadiversity in Madagascar. PLoS Biology 2008, 6, 0943–0946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaglica, V.; Sajeva1, M.; McGough, H. N.; Hutchison, D.; Russo, C.; Gordon, A. D.; Ramarosandratana, A., V.; Stuppy, W.; Smith, M., J. Monitoring internet trade to inform species conservation actions. Endangered Species Research 2017, 32, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World’s top exports. Madagascar’s Top 10 Exports. 2019. Available online: http://www.worldstopexports.com/madagascars-top-10-exports/ (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Jacobson, S. K.; Lopez, A. F. Biological impacts of ecotourism: Tourists and nesting turtles in Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica. Wildlife Society Bulletin 1994, 22, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, A. M.; Christiansen, F.; Martinez, E.; Pawley, M. D.; Orams, M. B.; Stockin, K. A. Behavioural effects of tourism on oceanic common dolphins, Delphinus sp., in New Zealand: The effects of markov analysis variations and current tour operator compliance with regulations. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0116962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C. Title of Unpublished Work. Abbreviated Journal Name.

- Author 1, A.B. (University, City, State, Country); Author 2, C. (Institute, City, State, Country). Personal communication, 2012.

- Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D.; Author 3, E.F. Title of Presentation. In Proceedings of the Name of the Conference, Location of Conference, Country, Date of Conference (Day Month Year).

- Author 1, A.B. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis, Degree-Granting University, Location of University, Date of Completion.

- Title of Site. Available online: URL (accessed on Day Month Year).

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TABLE 1a | ||||||||||||

| Number of tourists arriving on Madagascar* | 344348 | 375010 | 162687 | 19052 | 225055 | 255942 | 196375 | 222374 | 244321 | 293185 | 255460 | 291299 |

| Tourist income generation (US$ millions) | 313 | 459,65 | 178,5 | 211,1 | 262,49 | 279,81 | 390,42 | 649,62 | 585,38 | 748,297 | 668,262 | |

| TABLE 1b | ||||||||||||

| Number of ecotourists (17%; Wollenberg et al., 2011) | 58539 | 63752 | 27657 | 3239 | 38259 | 43510 | 33384 | 37804 | 41535 | 49841 | 43428 | 49521 |

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TABLE 1a | ||||||||||||

| Number of tourists arriving on Madagascar* | 344348 | 375010 | 162687 | 19052 | 225055 | 255942 | 196375 | 222374 | 244321 | 293185 | 255460 | 291299 |

| Tourist income generation (US$ millions) | 313 | 459,65 | 178,5 | 211,1 | 262,49 | 279,81 | 390,42 | 649,62 | 585,38 | 748,297 | 668,262 | |

| TABLE 1b | ||||||||||||

| Number of ecotourists (17%; Wollenberg et al., 2011) | 58539 | 63752 | 27657 | 3239 | 38259 | 43510 | 33384 | 37804 | 41535 | 49841 | 43428 | 49521 |

| Genus | Species | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mantella | 68798 | ||

| Mantella betsileo | 22737 | 33.0 | |

| Mantella baroni | 21110 | 30.7 | |

| Mantella nigricans | 7306 | 10.6 | |

| Mantella pulchra | 5969 | 8.7 | |

| Phelsuma | 65329 | ||

| Phelsuma lineata | 17939 | 27.5 | |

| Phelsuma quadriocellata | 15534 | 23.8 | |

| Phelsuma laticauda | 14124 | 21.6 | |

| Phelsuma madagascariensis | 10563 | 16.2 | |

| Furcifer | 59722 | ||

| Furcifer pardalis | 19029 | 31.9 | |

| Furcifer lateralis | 15908 | 26.6 | |

| Furcifer oustaleti | 11268 | 18.9 | |

| Furcifer verrucosus | 11312 | 18.9 | |

| Uroplatus | 30335 | ||

| Uroplatus sikorae | 10059 | 33.2 | |

| Uroplatus fimbriatus | 6170 | 20.3 | |

| Uroplatus phantasticus | 5002 | 16.5 | |

| Uroplatus ebenaui | 4202 | 13.9 | |

| Brookesia | 6686 | ||

| Brookesia superciliaris | 1927 | 28.8 | |

| Brookesia stumpffi | 1657 | 24.8 | |

| Brookesia thieli | 1326 | 19.8 | |

| Brookesia therezieni | 1169 | 17.5 |

| Genus | Species | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pachypodium | 22967 | ||

| Pachypodium spp | 7532 | 32.8 | |

| Pachypodium brevicaule | 4219 | 18.4 | |

| Pachypodium densiflorum | 4232 | 18.4 | |

| Pachypodium eburneum | 2352 | 10.2 | |

| Euphorbia | 11608 | ||

| Euphorbia primulifolia | 3184 | 27.4 | |

| Euphorbia spp | 1222 | 10.5 | |

| Euphorbia itremensis | 1088 | 9.4 | |

| Euphorbia guillauminiana | 1029 | 8.9 | |

| Operculicarya | 4175 | ||

| Operculicarya pachypus | 3337 | 79.9 | |

| Operculicarya decaryi | 430 | 10.3 | |

| Operculicarya hyphaenoides | 408 | 9.8 | |

| Angraecum | 1632 | ||

| Angraecum urschianum | 113 | 6.9 | |

| Angraecum breve | 95 | 5.8 | |

| Angraecum germinyanum | 95 | 5.8 | |

| Angraecum teretifolium | 89 | 5.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).