Religious Chanting, a Practice Different from All Others

Among the different types of meditative practices, religious chanting plays a significant role because it has a religious/spiritual dimension, a dimension that has a significant impact on the state of mind (Dick et al. 2014; Hotho et al. 2022). Chanting is a meditative practice that is prevalent worldwide and plays a central role in many religious and secular traditions. It is a widespread and ancient practice that has been used by many different cultures for centuries. In Buddhism, Sufism, Hinduism, and Yogic traditions, chanting is believed to be a way of altering states of awareness, reaching full human potential, and connecting with the ultimate reality of the universe. Indigenous Australians use chanting to communicate with ancestors and spiritual beings. In America, the Navaho chant to prevent illness and in sacred celebration ceremonies. In India, the chanting of ancient texts is a form of spiritual worship and may be used to transcend awareness. Jewish cantillation is another form of chanting and is used for transformation and worship (Perry et al. 2022). All over the world, chanting is the central practice of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhims as described in detail below. Chanting involves the repetition of a chosen phrase, word, or syllables, while disregarding distractions. In some traditions, the sound recited is referred to as a mantra or prayer and is considered a devotional form of music or meditation. Chanting can be practiced silently, vocally, alone or in unison with others as a form of synchronous vocalization and movement.

At variance with extensive research on various types of non-religious meditation practices such as, for example, mindfulness (Pommy et al. 2023), research on the neural correlates of religious chanting is in its early stages. An observational study performed in 2019, showed that the functional effects of religious chanting are not due to changes of peripheral cardiac or respiratory activity, nor due to implicit language processing. The Authors of this study suggest that the neurophysiological correlates of religious chanting are likely different from those of meditation and prayer, and would possibly induce distinctive effects. In other words, religious chanting may have an unique impact on the brain that is different from the impact of meditation or prayer (Gao et al. 2019).

Two interesting observations on the differences between religious chanting, in this case Buddhist religious chanting, and Catholicism, a religion based on prayer, came from Italy, a predominantly Catholic country where, however, there are about 160,000 Buddhists, a number that constitutes approximately 0.3% of the Italian population. Buddhism in Italy is the third most widespread and practiced religion, after Christianity and Islam. Among the different denominations, followers of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism constitute the largest group with 75,000 members that is about half of the whole Italian Buddhist believers (Bragazzi et al. 2019). It is worth noting that Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism is a religion officially recognized by the Republic of Italy.

The practice of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism originated in Japan in 1253 and consists in the recitation of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. The meaning of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo is complex and has been interpreted in different ways. The word Nam derives from the word namas in Sanskrit and can be translated as "devotion" in English. Myoho-Renge-Kyo is the title of the Lotus Sutra in its Japanese transliteration. The Lotus Sutra is a Mahayana Buddhist scripture that Nichiren Daishonin, the founder of this denomination of Buddhism, taught was the highest and most perfect teaching of the Buddha. Therefore, a simplified translation in English could be "Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra." Believers of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism recite (chant) Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo vocally every day for a variable number of times, keeping their eyes open and focused on the Object of Worship as per the Teachings of Nichiren Daishonin (The Major Writings 1979a; Watson 1993). The following excerpt from a guidance given by the Fifty-ninth High Priest of Nichiren Shoshu, Nichiko Shonin, explains how believers should practice: "The Daimoku (Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo) that we chant must be performed attentively and diligently. When chanting, we should not have trivial thoughts in our minds. The speed should not be too fast and our pronunciation should not be slurred. We must maintain a medium pitch and chant calmly, resolutely and steadily. There is no established number of Daimoku that we must chant. The amount depends on individual circumstances. . . . When we chant, the entire body should feel a tremendous surge of joy." (Nichiren Shoshu Basics of Practice, p.19)

A first study published in 2018 found that practitioners of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism in Italy had higher levels of optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and perceived social support than non-practicing Roman Catholic Church believers and Atheists (Giannini et al. 2018). The study also found that Buddhists were more extraverted than the other groups, and they appeared less tough-minded than Catholics. Significant differences were also observed in primary personality factors. The study's findings suggest that the assiduous practice of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism may have a number of psychological benefits, including increase of optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, perceived social support, and extraversion. The Authors of this study also found that there were no significant differences between Catholics and Atheists in terms of their psychological resources. However, they did find that Buddhists had significantly higher levels of psychological resources than both Catholics and Atheists. The Authors concluded that this difference was likely due to the religious practice of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism, which includes the assiduous chanting of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo and practice within a community of believers. A second study published in 2019, surveyed 391 practitioners of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism in Italy (Bragazzi et al. 2019). The results of this study were consistent with those of the previous study. Buddhists reported using adaptive coping strategies, having a predominant internal locus of control, and having a low psychopathological profile when compared to normative standard scores. In particular, Buddhists reported using a variety of adaptive coping strategies, such as problem-solving, seeking social support, and positive reappraisal. These strategies are thought to be helpful in managing stress and adversity. Buddhists also reported having a predominant internal locus of control, which means that they believe that they have control over their own lives. This belief is thought to be associated with a sense of empowerment and resilience. Finally, Buddhists showed a low psychopathological profile when compared to normative standard scores. This means that they were less likely to experience symptoms of mental illness, such as anxiety, depression, and stress. The findings of these two studies suggest that the practice of Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism is associated with a number of psychological benefits, including increased use of adaptive coping strategies, predominant internal locus of control, and low psychopathological profile (Giannini et al. 2018; Bragazzi et al. 2019). Although the two studies quoted above did not evaluate the effects of chanting on the immune system, it may be logically assumed that reduction of stress and sense of empowerment were associated with improved immune system function. Using the logics expounded by Chandran et al. (2021), chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo can be taken as an example of voluntarily improving the function of the immune system as well as other systems such as the central nervous and the endocrine system. It may also be argued that chanting affects immunoception, that is the process by which the brain receives and interprets signals from the immune system. This allows the brain to monitor the body's immune status and to take steps to regulate the immune system, either to boost it or to dampen it down.

Immunoception, a Two-Way Street between the Brain and the Immune System

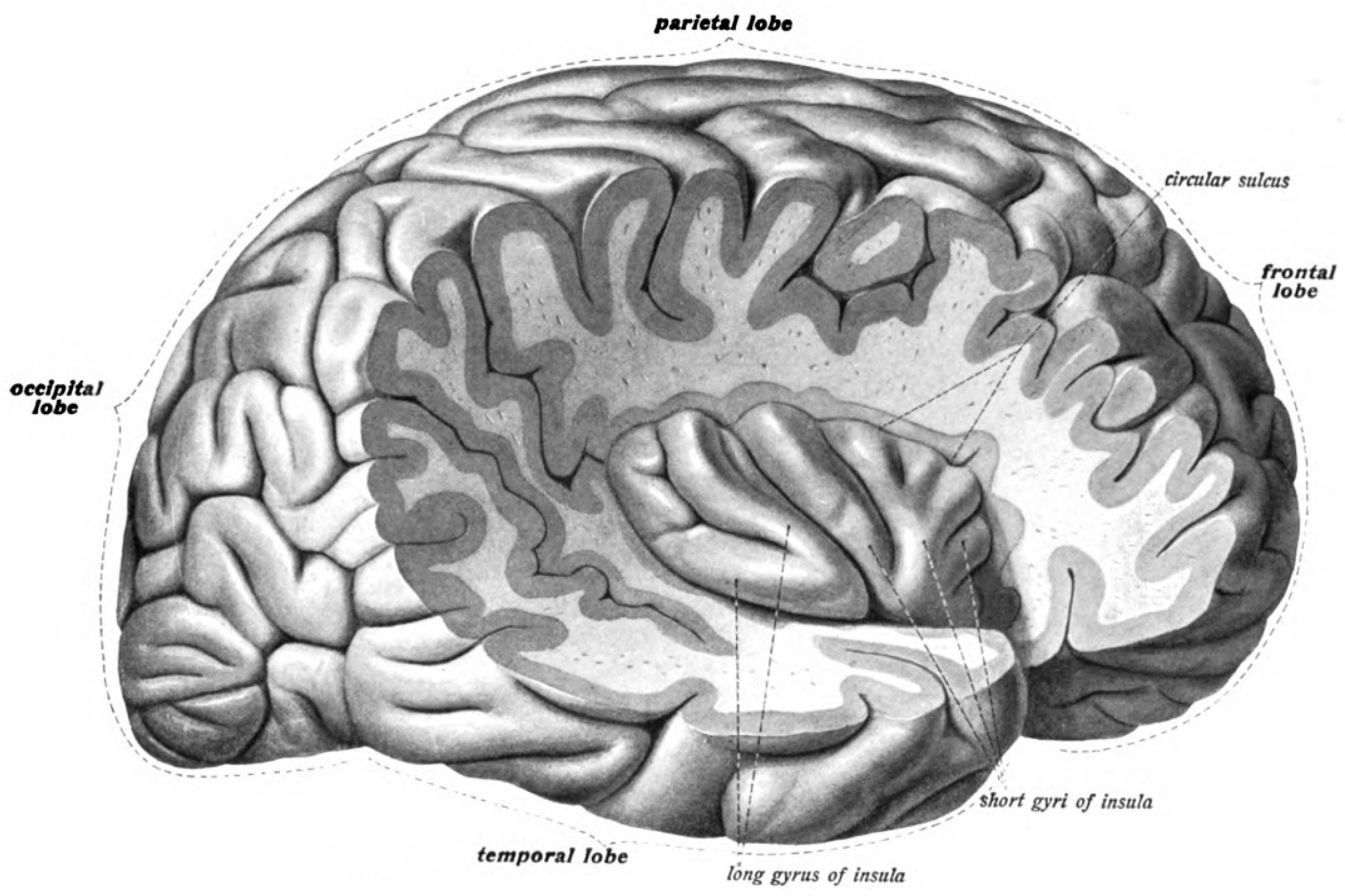

In recent years, there has been growing evidence that the brain is constantly monitoring the state of the immune system and can adjust immune responses based on this information. This two-way communication, which is called immunoception, can be considered one of the senses; it is based on the concept of interoception given that the insular cortex, a key area of the brain for interoception, has been shown to store also immune representations.

Figure 1.

The insular cortex of the right side, exposed by removing the opercula. An anatomical illustration from the 1908 edition of Sobotta's Anatomy Atlas.

Figure 1.

The insular cortex of the right side, exposed by removing the opercula. An anatomical illustration from the 1908 edition of Sobotta's Anatomy Atlas.

A recent study describes on the role of the insular cortex in immune representation and regulation (Rolls 2023). This study presents emerging evidence that the brain stores immune-related information and uses this information to orchestrate physiological processes and regulate immune activity. However, there are many open questions in this field. For example, it is not known what kind of immune information is acquired by the brain, how it is conveyed to the central nervous system, which brain areas and neural networks record this information, how this information is integrated with previously available inputs, whether the brain can update information stored in the insula, and how the brain executes its control over the immune response. Despite these open questions, the potential impact of brain representation and regulation of immunity on the understanding of physiology is enormous. These concepts challenge the common perception of immunological memory as being stored solely by the immune system. They also suggest that autoimmune diseases can be triggered by neuronal stimuli, providing new mechanistic insights into psychosomatic disorders. Finally, they could pave the way for novel therapeutic modalities that regulate immunity by manipulating the brain. Among these modalities, voluntary improvement of the immune system function as suggested by Chandran et al. (2021) appears most promising.

At the basis of the notion of immunological memory stored in the brain is the concept of the immunengram. The neuronal representation of the immune state by the brain, specifically by the insular cortex, suggests that there is a specific neuronal trace that captures immune information, an immunengram. The classical neuroscience concept of an engram refers to the neural substrate underlying the storage and retrieval of memories, namely, the physical representation of memories in the brain. Although the exact nature of the engram is still a topic of active research and debate, it is generally accepted that memories are stored as patterns of activity across networks of neurons rather than in isolated individual cells. The engram is not limited to a single modality and can be affected by various inputs. For example, a recent study in mice demonstrated that long-term associative fear memory stored in neuronal engrams in the prefrontal cortex determines whether a painful episode shapes pain experience later in life (Stegeman et al. 2023). Under conditions of neuropathic pain, prefrontal fear engrams expand to encompass neurons representing nociception and tactile sensation, leading to pronounced changes in prefrontal connectivity to fear-relevant brain areas. This highlights the complexity of engrams at the brain level.

However, an immunengram is expected to have additional, unique properties. For example, it is expected to be multimodal, incorporating information from both the immune system and the nervous system. Additionally, it is likely to be plastic, changing in response to new experiences and environmental cues. Finally, it is likely to be dynamic, with different aspects of the immunengram being activated at different times, depending on the context.

The concept of an immunengram suggests that the brain can form a specific neuronal trace in response to immunological events. This trace can be retrieved upon reactivation of the same neuronal ensembles. However, unlike a neuronal engram, which is specific to the brain and for which neuronal activity is sufficient to manifest the required behavior, it is hypothesized that the immunengram is not limited to the neuronal component. It also involves changes in cells in the periphery and, potentially, in specific immune clones (Rolls 2023). This distributed trace is necessary because the immune system operates as a complex and distributed network of cells and molecules. The brain can communicate with the immune system through a limited set of tools, mainly the autonomic nervous system. By forming a distributed trace, which involves changes in both neuronal circuits and peripheral tissue components, the brain can better communicate with and regulate the immune response in peripheral tissues. Tissue components, such as immune cells and neuropeptide receptors, can act as interpreters of the limited peripheral neuronal input and eventually recapitulate part of the complexity of the tissue's previous immune event. In other words, the distributed trace allows for more nuanced and adaptable communication between the brain and the immune system, which is crucial for effective immune regulation and response.

The concept of the immunengram has helped to advance the understanding of the relationships between the brain and the immune system. However, the fine physical substrate of the immunengram remains elusive. As mentioned above, it is postulated that the immunengram is stored in neural circuits based on synapses. When the brain detects an immune event, establishes new circuits or changes pre-existent ones and these changes could be the basis for the immunengram. The immunengram and the engram are both thought to be physical traces of experiences; however, it is not clear if they are aware of themselves, in other words, if they have consciousness. Is the experience aware of itself? It is possible that the immunengram and the engram are nor conscious per se, but are simply parts of the brain's complex system for processing experiences and generating consciousness. These points raise the question of what consciousness is and how the immune system interacts with it, or even if the immune system is itself conscious. These are important questions that will be addressed in the next section.

Consciousness and the Immune System, the Orch OR Theory

Consciousness is one of the most fascinating and mysterious aspects of the human experience even though, it must be stated, consciousness is not exclusive to humans; animal, plants, inanimate objects, and the universe itself are thought to have the attribute of consciousness (Hameroff and Penrose 2014; Lamme 2018). In this regard, Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism states "Life at each moment encompasses both body and spirit and both self and environment of all sentient beings in every condition of life as well as all insentient beings in every condition of life, as well as insentient beings - plants, sky, and earth, on down to the most minute particles of dust. Life at each moment permeates the universe and is revealed in all phenomena (The Major Writings 1979b).

As far as humans are concerned, consciousness is described as the ability to be aware of oneself and the world around oneself, and it is essential for the ability to think, feel, and act. However, consciousness is also incredibly complex, and we do not yet fully understand how it works. There are many different theories of consciousness, each with its own unique perspective on how consciousness arises. Some theories focus on the brain's electrical activity or the firing of neurons. Others focus on the brain's structure or its chemical composition. Still others focus on the role of the environment or the mind-body connection. The most prominent theories of consciousness are listed below:

The Global Neuronal Workspace (GNW) theory proposes that consciousness arises from a network of neurons that are distributed throughout the brain. These neurons are thought to work together to create a global workspace, which is a mental space where information can be shared and processed.

The Integrated Information Theory (IIT) proposes that consciousness arises from the amount of information that is integrated within a system. The more integrated a system is, the more conscious it is.

The Higher-Order Thought (HOT) theory proposes that consciousness arises from the ability to think about one's own thoughts. In other words, we are conscious of something when we can think about it and reflect on it.

The Epiphenomenal Theory proposes that consciousness is an epiphenomenon, which means that it is a by-product of other physical processes in the brain. In other words, consciousness does not have any causal power, and it does not play any role in our thoughts, feelings, or actions.

The Quantum Theory of Consciousness proposes that consciousness arises from quantum mechanical processes in the brain. These processes are thought to allow for the brain to process information in a way that is not possible with classical physics. This latter theory, better known as the Orch OR (Orchestrated Objective Reduction) theory, is the most complete theory of consciousness (Hameroff 2021).

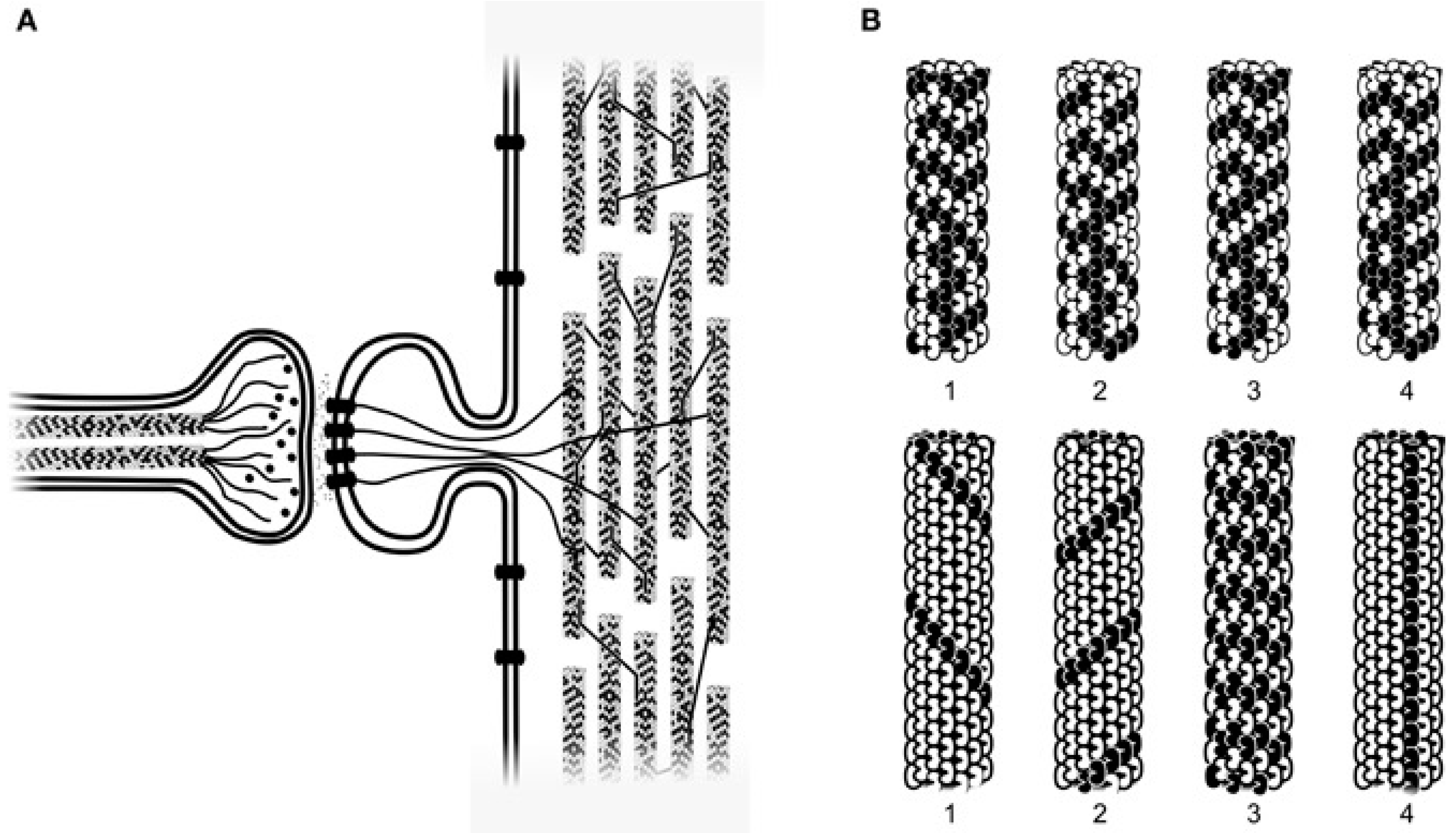

Orch OR is an original theory of consciousness expounded almost thirty years ago by English Nobel Laureate Sir Roger Penrose, and Professor Stuart Hameroff of Arizona State University (for rev., see Hameroff and Penrose 2014, and Hameroff 2023). The core tenet of the theory is the notion that consciousness originates inside brain neurons, mediated by quantum computations occurring in the context of cytoskeletal structures, the microtubules, and, more precisely, in the context of the helical structure of the main protein constituting microtubules, i.e. tubulin.

Tubulin has a number of properties that make it well-suited for quantum processing. First, tubulin (both alpha and beta) is relatively small with a molecular weight of around 50 kDa. This makes it less susceptible to decoherence, which is the process by which quantum states are lost due to interaction with the environment. Second, tubulin is a highly organized protein. It has a specific structure that allows it to form into hollow elongated cavities, the microtubules, with a diameter of about 25 nanometers. This structure helps to protect the quantum states of tubulin from decoherence. Third, tubulin is a dynamic protein. It can undergo a number of conformational changes. This allows tubulin to form into different structures, which can be used to encode information and perform quantum computations. Fourth, tubulin in the context of microtubules can function as a Fabry-Perot interferometer able to detect the interaction between sound and electromagnetic waves (Ruggiero 2023). The Orch OR theory hypothesizes that tubulin forms into oscillating dipoles in microtubules. These oscillating dipoles can interact with each other to form qubits, which are the basic units of quantum information. The qubits in microtubules are then thought to be orchestrated by connecting proteins, such as microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), to perform quantum computations. These quantum computations are thought to be the basis of consciousness. In other words, consciousness is dependent on biologically ‘orchestrated’ coherent quantum processes occurring inside microtubules within brain neurons as well as in any other cell possessing a cytoskeleton. In the specific case of the brain, these quantum computations correlate with, and regulate, neuronal firing. This orchestrated OR activity leads to moments of consciousness that could also be defined as awareness and/or choice.

The notion of consciousness as a series of discrete moments (quanta), rather than a single, unbroken flow, has been around for millennia. Hameroff and Penrose (2014) quote ancient Indian and Chinese Buddhist scriptures that estimate that the duration of each moment ranges from 13.3 to 20 ms. Interestingly, EEG studies agree with these estimates and it appears that we, as humans, have around 40 conscious moments per second. It should be noticed, however, that, according to the principle of ichinen sanzen, each moment of consciousness is constituted by three thousand aspects and, therefore, the fine granularity of consciousness is much greater than simply 40 moments per second. Ichinen sanzen is a Buddhist concept that means "three thousand realms in a single moment of thought [or a single life-moment]." It is a central teaching of the Lotus Sutra, and it is one of the most important concepts in Mahayana Buddhism. Ichinen sanzen is based on the idea that all of reality is interconnected. There is no separation between the individual and the universe, between the mind and the body, or between the past, present, and future. Everything is interconnected in a single moment of thought. The concept of ichinen sanzen is often used to explain the nature of enlightenment. When a person attains enlightenment, they see the world as it truly is, without any separation or division. They see that all of reality is interconnected, and that they are a part of this interconnected web of life. Ichinen sanzen is a non-dualistic concept. This means that there is no separation between the self and the world, between the observer and the observed. Everything is interconnected and interdependent.

Ichinen sanzen is a dynamic concept. This means that reality is constantly changing and evolving. There is no one static truth, but rather a multitude of truths that are constantly interacting with each other. Ichinen sanzen is a liberating concept. When we realize that we are interconnected with all of reality, we can let go of our attachments and fears. We can live in the present moment and enjoy the journey of life. The following excerpt from the writing (Gosho) of Nichiren Daishonin entitled "On the Object of Worship Manifesting the True Buddha's Entity and his Englightement, Originating in the Fifth Five-hundred-year Period after the Buddha's Passing" (Nyorai metsugo gogohyakusai ni hajimu kanjin no honzon-sho. April 25, 1273) states:

"Observation of the mind means to have an insight into the ten worlds by perceiving one's mind. In other words, although one can see the six sense organs of others, he does not know his own because he cannot see them. Only by looking into a clear mirror can he see them for the first time. Even though the six paths and the four noble worlds are expounded in some parts of various sutras, without a clear mirror, such as the Lotus Sutra or the Great Teacher Tiantai's "Great Concentration and Insight" (Maka shikan), one will never become aware of the ten worlds, hundred worlds and thousand factors, and ichinen sanzen (three thousand realms in a single life-moment) that one possesses within oneself.".

(Gosho, p. 646)

Moving from lofty Buddhist concepts to more pedestrian molecular biology, it is worth noting that the aromatic amino acids in the sequence of tubulin play a role in quantum information processing. The aromatic amino acids of tubulin are thought to be important for quantum information processing in Orch OR for a number of reasons. First, they have large, ring-shaped structures that can absorb electromagnetic radiation. This makes them well-suited for quantum information processing. Second, they are arranged in a regular pattern in tubulin, which helps to stabilize their quantum states. Third, they are relatively isolated from the environment, which helps to protect their quantum states from decoherence. Tryptophan has the largest ring of all the aromatic amino acids, and it is therefore the most efficient at absorbing electromagnetic radiation. This makes it an ideal candidate for forming oscillating dipoles in microtubules. Phenylalanine and tyrosine also have ring-shaped structures, but they are not as large as the ring of tryptophan. This makes them less efficient at absorbing electromagnetic radiation, but they are still thought to play a role in quantum information processing in Orch OR.

The emphasis placed on microtubules and tubulin as the physical substrates of consciousness make the Orch OR theory unique among other theories of consciousness because it implies that everything that has a cytoskeleton has the attribute of consciousness, thus dethroning the brain from its position of preeminence. Therefore, also those forms of life defined non-sentient beings, such as plants or microbes, having a cytoskeleton, have the attribute of consciousness (Gardiner 2012; Reddy and Pereira 2017). Another important consequence of Orch OR consists in the notion that all cells in a multicellular organisms share the same consciousness. Taking the human body as an example, all cells share the same coding sequences of DNA and, therefore, all proteins of an individual - including tubulin - have the same amino acid sequence. If consciousness arises from computations inside microtubules and if these computations are based on tubulin, then all cells of an individual not only have consciousness, but they also have the same type of consciousness that, by definition, will be different from that of another individual who may have a different arrangement of tubulin because of polymorphisms (Garcia-Aquilar et al. 2023). Therefore, it is possible that the immunengram does not reside uniquely in the insular cortex as a result of neural connections; it may well reside in the entangled consciousness of individual cells of the immune system. As a matter of fact, since all cells of an individual derive from a single one, the zygote, and since they share the same DNA coding sequences, it is logical to assume that they are entangled both from the point of view of classical molecular biology as well as from the point of view of quantum mechanics. According to this concept, there is no communication, strictly speaking, between the central nervous system and the immune system; events of consciousness would occur simultaneously in both systems without any need of "communicating". Since OR is based on the fundamentals of quantum mechanics and the geometry of space-time, and since Orch OR postulates that there is a connection between the events occurring in the brain and the basic structure of the universe (Hameroff and Penrose 2014), it is not surprising that there could be a connection, at the quantum level, between the consciousness of the brain and that of the immune system. According to what expounded above, the immune system is thought to have its own consciousness, separate from the brain. This raises the question of whether meditation or religious chanting can have a direct effect on the immune system, in addition to their effects on the brain. In other words, could meditation or religious chanting somehow "talk" to the immune system, bypassing the brain?

Religious Chanting May Act Directly on Cells of the Immune System as It Happens with Cardiomyocytes

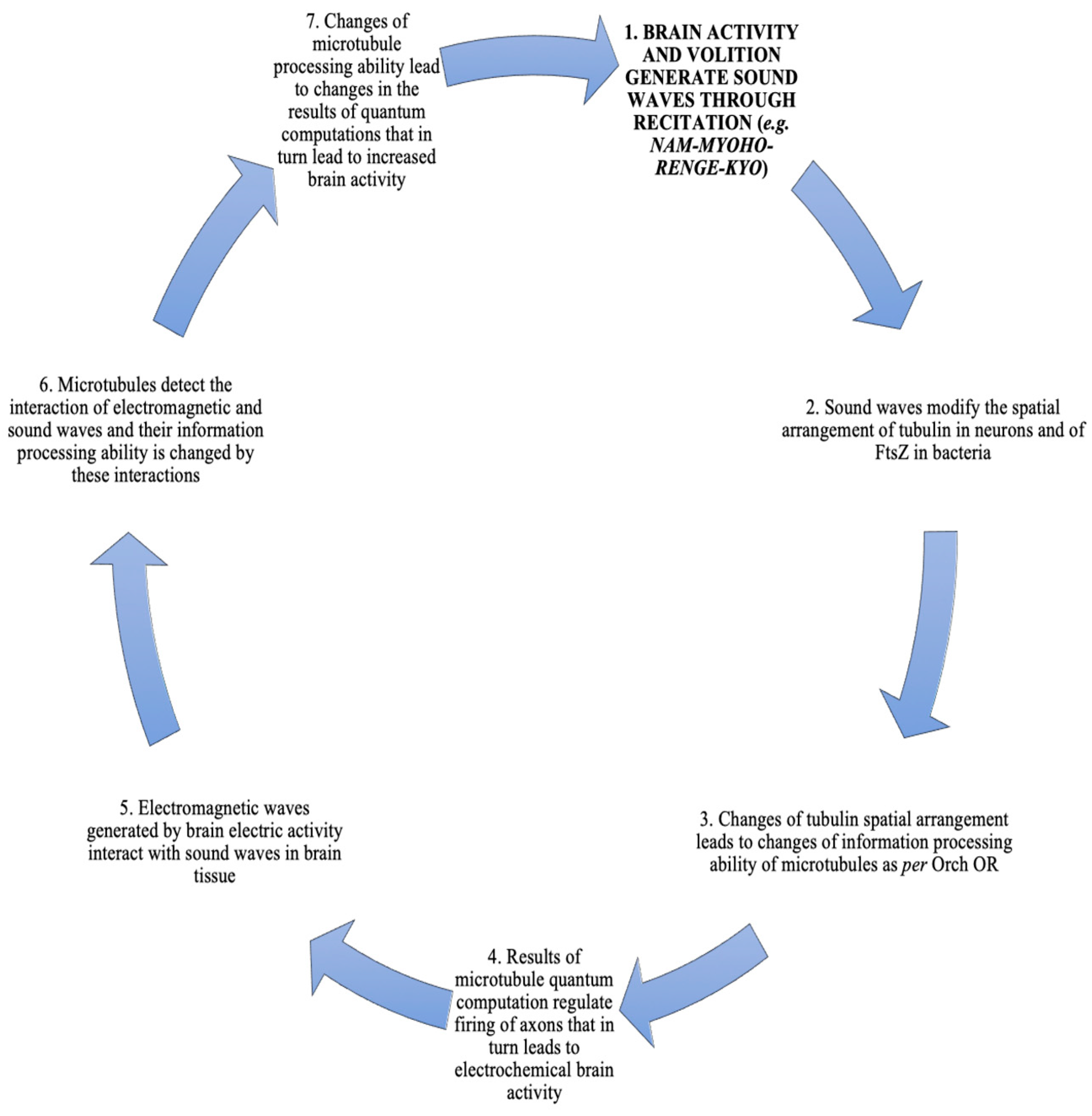

It was recently hypothesized that chanting

Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo generates an unique electromagnetic/vibrational signature that may be interpreted by microtubules of neurons acting as Fabry-Perot interferometers, thus leading to increased brain activity and level of consciousness (Ruggiero 2023).

Figure 3, shows the recursive functions generated by chanting.

According to this model, the sound waves generated by vocalization modify the spatial arrangement of tubulin in neurons in a manner superimposable to that observed in cardiomyocytes (Dal Lin et al. 2021); these changes modify the computational characteristics of tubulin. Modified computations lead to modified regulation of axonal firing and, thus, to modified electrical brain activity. The electromagnetic waves generated by the modified brain electrical activity interact with the sound waves generated by chanting since the nervous tissue is a medium whose electrical properties are affected by mechanical strain. Microtubules, performing the function of a Fabry-Pérot interferometer, are able to detect and interpret the interaction of electromagnetic and sound waves and are modified by such an interaction, thus further modifying their computational ability that in turn results in modified electrochemical brain activity. The repetitive, voluntary, generation and exposure to sound waves constitute an example of recursion that leads to increased level of brain activity and, hence, consciousness.

In the previous paragraph, the concept of "sound" referred to vocalization has been utilized to indicate oscillation in pressure, stress, particle displacement and velocity, and so on. Here it is important to clarify some concepts, in particular in the context of the quantum characteristics of sound as they relate to the interactions of sound and electromagnetic waves. Sound waves need a medium to propagate through and the medium can be air, water, or a solid; electromagnetic waves can propagate in all types of mediums including vacuum. The only requirement is that the medium must be able to support electric and magnetic fields. The medium where sound waves propagate needs to have internal forces, such as elastic or viscous forces, in order for sound waves to propagate. A sound source creates vibrations in the medium. These vibrations propagate as longitudinal and transverse waves. Longitudinal waves are waves in which the particles of the medium vibrate in the same direction as the wave is propagating. Transverse waves are waves in which the particles of the medium vibrate perpendicular to the direction of the wave propagation. Sound and electromagnetic waves can be reflected, refracted, or attenuated by the medium. Reflection is when a wave bounces off of a surface. Refraction is when a wave bends when it passes from one medium to another. For sound waves, attenuation is when the amplitude of a sound wave decreases as it propagates through the medium. For electromagnetic waves, attenuation is the loss of energy of an electromagnetic wave as it travels through a medium. There are a number of factors that can cause attenuation of electromagnetic waves, including absorption, scattering and diffraction:

For sound waves, the pressure, displacement, and velocities of the medium vary in time and space at a fixed distance from the sound source. This is because the sound waves are constantly propagating and the medium is constantly reacting to the sound waves. Sound waves can produce pressure waves that can affect cells or their structures and, in this regard, their biological effects differ greatly from those of electromagnetic waves. The pressure exerted by sound waves can cause microvibrations, or even resonances, in cells. Resonance is when the frequency of a sound wave matches the natural frequency of a cell or its structure. When this happens, the cell or structure can vibrate more easily, which can have a number of effects on the cell. For example, it has been shown that bacterial cells can respond to specific single acoustic frequencies. When these frequencies are applied to bacterial cells, the cells can change their shape, motility, and gene expression. In some cases, the cells can even emit sounds themselves (Matsuhashi et al. 1998).

The effects of sound waves on cells can be complex and depend on a number of factors, including the frequency, intensity, and duration of the sound wave.

Acoustic vibrations, in the form of single frequencies, noise, or music, can have a number of effects on cells. These effects can include changes in proliferation, viability, and hormone binding. Acoustic vibrations can also affect the spatial interaction between cells, their individual and collective behavior, and their intracellular and intercellular organization. These effects are important for regulating the function of cells. Mechanical forces, such as those exerted by sound pressure on surface-adhesion receptors, such as integrins and cadherins, can be transmitted along the cytoskeleton to distant sites in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Haupt and Minc 2018) thus affecting a number of cellular functions including regulation of gene expression, and cytoskeleton-based consciousness.

However, the traditional phenomenological analysis of the interactions of sound waves with cells and their environment in biological systems is not sufficient, and a more complete understanding can be achieved by considering the quantum nature of the vibrational modes of the electric dipoles that characterize the molecules involved in the inter- and intra-cellular systems. The molecular electric dipole vibrations can be described as phonons, which are the quanta associated to the deformation wave, namely the elastic wave. This means that the sound waves can interact with the cells and their environment at the molecular level, by exciting the phonons. This interaction can have a number of effects, including the dynamical formation of fractal and multifractal self-similarity. The quantum dynamical analysis of the sound wave interaction with cells and their environment provides a deeper understanding of this process, and that it can be used to develop new methods for manipulating cells and their environment using sound waves.

Even more complex are the interactions between sound and electromagnetic waves in the context of the cell that is a medium able to propagate both types of waves. In general, sound waves and electromagnetic waves cannot interact directly with each other. This is because they are different types of waves that propagate through different mechanisms. However, if they both share a common medium, and that medium has electrical properties that vary with mechanical strain, as it is the case of the cell, the two undulatory phenomena can interact. This is because the mechanical strain caused by the sound wave can change the electrical properties of the medium, which can then affect the propagation of the electromagnetic wave. This interaction is called piezoelectricity and piezoelectricity has been found in proteins (Yuan

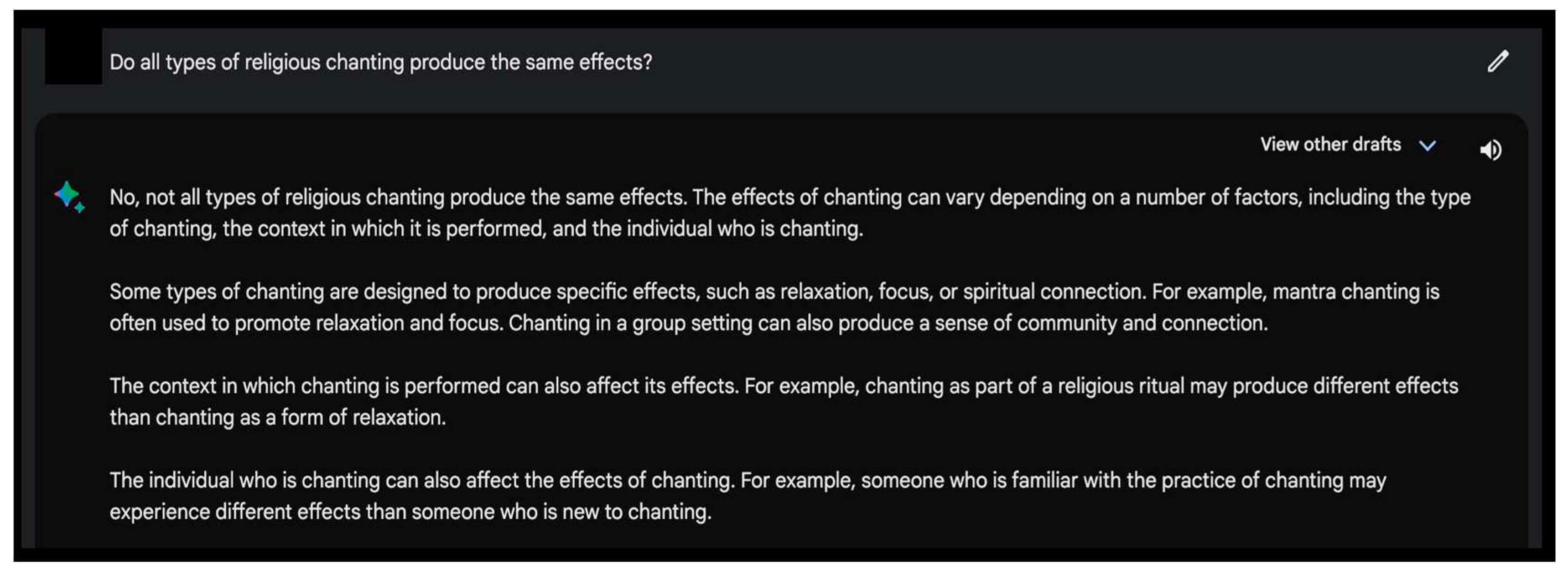

et al. 2019). Piezoelectric materials are materials that have the property of generating an electric charge when they are mechanically deformed. This property is caused by the alignment of electric dipoles in the material. When the material is deformed, the dipoles are aligned in the direction of the deformation, which creates an electric field. The reverse effect is also possible. When an electric field is applied to a piezoelectric material, it can cause the material to deform. This is because the electric field aligns the dipoles in the material, which creates a mechanical strain. A microtubules can be envisaged as an etalon (or Fabry-Pérot interferometer, or resonant cavity) with the cavity filled with a piezoelectric material, that is constituted by the meshwork of luminal proteins stabilizing the microtubule (Ichikawa and Bui 2018). Resonant standing waves (either electromagnetic or acoustical) will produce fixed patterns of electromagnetic or acoustic properties in microtubules, thus generating unique patterns of signature of consciousness. If consciousness is not relegated to neurons, but emerges from quantum computations in all cells that have a cytoskeleton, then it is not difficult to imagine that religious chanting acts directly on the cells of the immune system. However, based on what described above, each type of chanting will generate its own peculiar pattern of consciousness because the results of the interactions between sound and electromagnetic waves is unique for each type of chanting and, therefore, the effects of the different types of chanting are not interchangeable. It is interesting to note that even the artificial intelligence seems to agree with this point. When Bard, a large language model chatbot developed by Google artificial intelligence was asked "Do all types of religious chanting produce the same effects", it answered as reported in

Figure 4.

Therefore, based on the concepts expounded above, it is plausible that chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo acts directly on cells of the immune system who, thanks to the consciousness associated with microtubules and tubulin, may be able to interpret the positive and compassionate significance of chanting. This is exactly what happens with cardiomyocytes in vitro; these cells interpret the significance of acoustical signals and tubulin reacts differently if the cells are exposed to signals (phrases, music, or mantra) with a positive or a negative significance (Dal Lin et al. 2021). Interestingly, the most positive responses occurred when cells were exposed to a mantra, whereas the most negative responses occurred when cells were exposed to noises (Dal Lin et al. 2021).

The Immune System and the Brain; Two Different Ways of Acquiring and Elaborating Information

The brain acquires information about the world through a process called sensory perception. Sensory perception is the process by which the senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch) convert external stimuli into electrical signals that can be interpreted by the brain. The first step in sensory perception is the detection of a stimulus. This is done by specialized cells in sensory organs, such as photoreceptors in the eyes, hair cells in the ears, and taste buds on the tongue. When a stimulus is detected, it triggers a chain reaction of events that ultimately leads to the generation of an electrical signal. This electrical signal is then transmitted to the brain along a nerve pathway. The nerve pathway carries the signal to a specific region of the brain that is responsible for processing that particular type of sensory information. For example, signals from the eyes are sent to the visual cortex, signals from the ears are sent to the auditory cortex, and so on.

Once the signal reaches the brain, it is interpreted by a network of neurons. This network of neurons is able to recognize the pattern of the signal and to make sense of it. For example, the visual cortex is able to recognize the pattern of electrical signals that represent a particular object.

In addition to the five classical ones of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch there are other senses that have been identified and contribute to the collection of information. These additional senses are:

Balance: This sense is responsible for perception of gravity and orientation in space. It is also responsible for our ability to maintain balance. The sense of balance is located in the inner ear.

Proprioception: This sense is responsible for awareness of the position and movement of body parts. It is also responsible for the ability to coordinate movements. The sense of proprioception is located in the muscles, tendons, and joints.

Interoception: This sense is responsible for perception of internal stimuli, such as hunger, thirst, pain, and body temperature. The sense of interoception is located in the brain and throughout the body.

Thermoception: This sense is responsible for our perception of temperature. It is located in the skin and in the hypothalamus.

Nociception: This sense is responsible for perception of pain. It is located in the skin and in the spinal cord.

Immunoception: This is the sense by which the brain senses and regulates the immune system.

In addition to these senses, there are also some senses that are not well understood or that are only experienced by certain people. Some of these senses include:

Electromagnetic sense: This sense is hypothesized to allow some animals, such as sharks, to detect electromagnetic fields.

Magnetoception: This sense is hypothesized to allow some animals, such as pigeons, to sense the Earth's magnetic field. Recent evidence shows that also humans are capable of magnetoception (Chae et al. 2022)

Ultrasonic sense: This sense is used by some animals, such as bats, to navigate and hunt in the dark. We demonstrated that human neurons are also capable to respond to ultrasounds (Branca et al. 2018).

Pain empathy: This sense allows to feel the pain of others. It is thought to be mediated by mirror neurons in the brain.

Independently of the fact that there are five or fifteen senses, the information that the brain is capable of acquiring is limited by the physical limitation of the senses. Such a limitation constitutes what is called cognitive bottleneck (Borst et al. 2010), a concept that was first expounded by Aldous Huxley in his 1954 book "The Doors of Perception" where he proposed the idea that the brain acts as a reducing valve that limits the amount of information that we - and presumably all beings with a brain - are consciously aware of. He argued that the brain filters out most of the information that is coming in through our senses, and only allows us to focus on a small amount of information at a time.

However, if the brain is, or has, a reducing valve that limits the amount of information that we can process, the immune system does not appear to have such limitations. It has been known for a long time that the immune system is capable of acquiring information, learning, memory, and pattern recognition, thus being endowed with all the attributes of intelligence and consciousness (Farmer

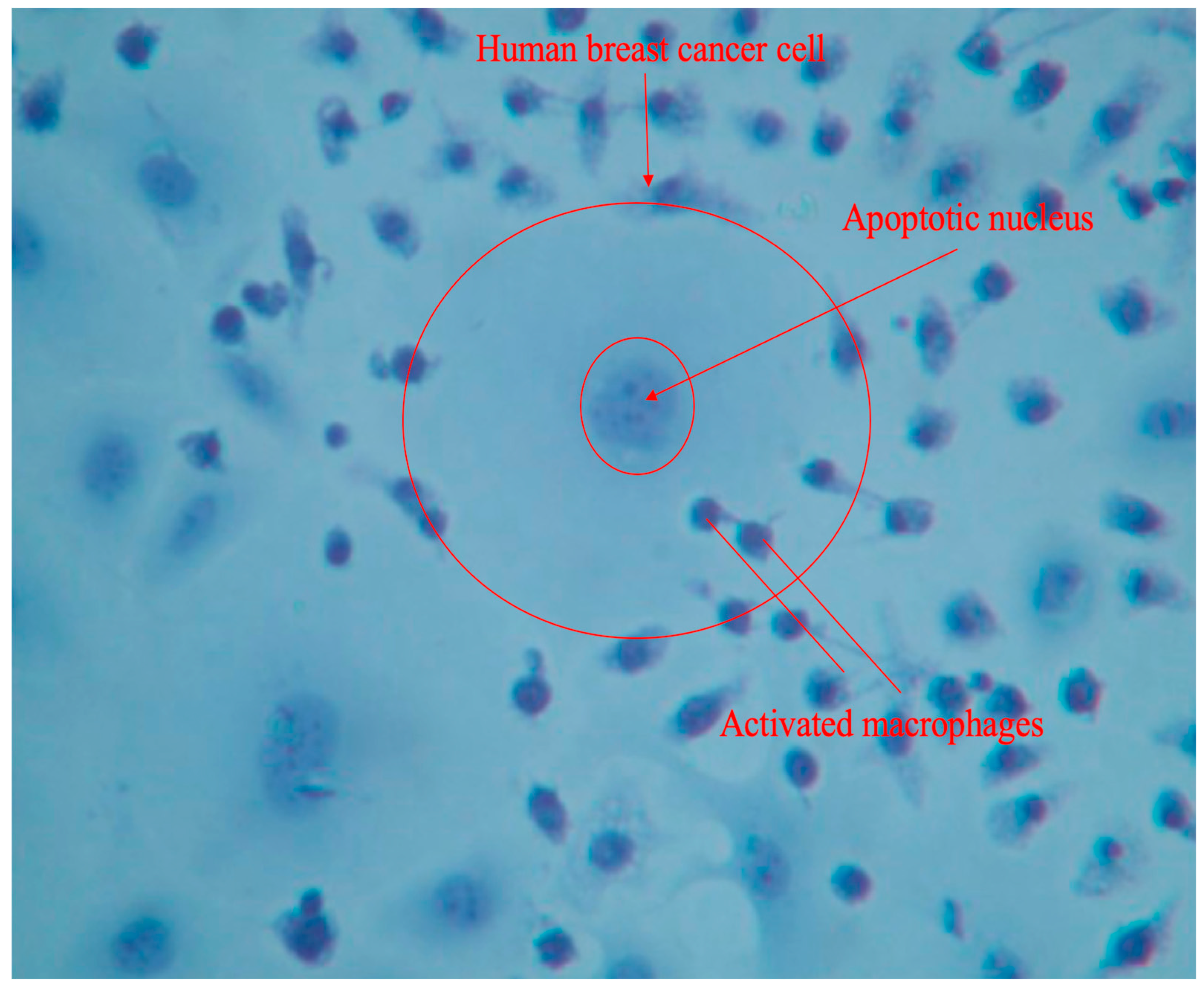

et al. 1986). The cells of the immune system acquire information in a variety of ways. For example, antigen presentation is the process by which antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present antigens to the immune system. APCs take antigens from pathogens and break them down into smaller pieces. In this context, one may think that the also amount of information that the immune system is capable of acquiring is limited in some way and certainly not greater than what is accessible to the brain The perspective changes, however, if one takes into account the process of phagocytosis, the process by which neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells engulf and destroy foreign particles, such as bacteria, viruses, cancer cells, cells with mutation, apoptotic cells, and cellular debris (

Figure 5).

By coming on contact with the information encoded in the DNA or RNA of what has been phagocytized, phagocytes acquire an enormous deal of information about the world. For example, the genome of each cancer cell is different (Talseth-Palmer and Scott 2011) and continuously mutates; considering that there are mutated cells in the healthy human body since fetal development (Paashuis-Lew and Heddle 1998), it is easy to conceive that the amount of information acquired by the cells of the immune system that take care of those mutated cells is enormous. However, this amount of information, albeit enormous, is still limited and it is questionable whether it may be greater than what is accessible to the brain. Where the immune system surpasses the amount of information accessible to the brain is in its interaction with the microbiome, an interaction that is essential for the functioning of the immune system and, more in general, of the entire organism (Belkaid and Hand, 2014). If we consider that the cells of the human microbiota - even not counting the trillions of viruses of the human virome (Koonin et al. 2021) - outnumber host cells by at least a factor of 10 and, more importantly from the point of view of information, the number of genes of the collective human microbiome is comparable to the number of atoms in the universe, we deduce that the amount of information accessible to the immune system is as vast as the universe (Harvard Medical School 2019).