1. Introduction

Nowadays in Spain, assisted reproductive treatments imply 9% the total annual number of pregnancies [

1] which are increasing year after year. This difficulty in conceiving generates a considerable amount of stress, frustration, and anxiety, and thus it is estimated that a great number of the patients at assisted reproductive technology services show clinical symptoms of emotional de emotional affectation [

2,

3,

4] which may have a negative impact on the mental health of couples, making them more vulnerable to depression and anxiety. And hence the importance of the psychological support during the process [

5,

6].

The state of emergency due to the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, temporarily affected the management of the activities of the Assisted Reproduction Units in Spain, as this type of services were not considered a health priority. Scientific societies related to these objectives –European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), Sociedad Española de Fertilidad (SEF), Asociación para el estudio de la Biología de la Reproducción, (ASEBIR)– recommended to postpone the start of new treatments until the end of the state of alarm, finish the ongoing cycles and do not transfer but have their embryos frozen. Fertility preservation cycles were only initiated in cancer patients, before gonadotoxic treatments [

7]. All this had an impact on patients who were waiting for their treatment and could not afford to delay it any longer. This situation caused an influence in the risk of psychological distress [

8].

There were no recent precedents for a pandemic of this magnitude, however, there is evidence that emotional distress had a strong influence in this situation, both on health professionals and general population. There was a generalized fear of contagion and feelings of anxiety and depression were common [

9,

10]. Fertility treatments normally require of multiple face-to-face appointments in which patients interact with a multidisciplinary team for the necessary tests, a routine which may spread the contagion. The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), as well as from other societies, recommended to suspend new treatments and non-urgent surgical procedures.

The aim of this study was to assess the level of anxiety of patients whose assisted reproduction treatments were either suspended or postponed until the end of confinement caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to evaluate the different sociodemographic variables associated to the emotional management of this situation.

2. Materials and Methods

Descriptive cross-sectional study conducted during April and May 2020. Participants recruitment followed a consecutive random sampling conducted during the confinement months among women included in the assisted reproduction program at the Canarias university hospital (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain), a tertiary hospital belonging to the Public Health System. All women included in the program were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were women aged 27-42 years who were receiving fertility treatments: (1) IVF-ICSI patients who had already started their treatment with analogues of GnRH (initial ovulation induction phase) or contraceptives, or those patients who had their medication but were waiting for their periods to start the treatment; (2) patients in the procedure cycle of frozen embryos transfer (FET); (3) patients undergoing the treatment of ovarian stimulation for artificial insemination (AI). Exclusion criteria were participation non-acceptance and not having initiated the reproductive process being currently under study.

2.1. Instruments

Psychological tests may evaluate multidimensional traits and subfactors, such as personality, anxiety, or depression. Each patient was administered a validated diagnostic test 1) anxiety: the STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Spanish adaptation: Spielberg, Gorsuch, Lushere (1983)) [

11]. The aim of the

STAI questionnaire is to evaluate two concepts: anxiety as state (emotional, transitory condition) and anxiety as a trait (stable tendency to experience and report negative emotions such as fear or worry). The time frame of reference in the case of anxiety as a state is “Right now, at this moment”, and in the case of anxiety as a trait is “In general, most of the time”. Each of these concepts, are measured through 20 items in a 4-Point Likert Scale response according to intensity (0=almost never /never; 1=something/sometimes; 2= very much/very often; 3= a lot/almost always). Total punctuation in each subscale ranges from 0 to 60 points. A STAI score of 34-36 was considered normal. This is a validated questionnaire and widely used in the literature to evaluate trait anxiety and state anxiety levels in both general and clinical populations, being also one of the most used by the Spanish psychologists Muñiz and Fernández-Hermida [

12]. State anxiety scale has obtained a Reliability Index rating of α=0.86 and the Trait anxiety scale a α=0.78, thus assuring the internal consistency reliability obtained by the sample.

Secondly, a structured survey developed by the Human Reproduction Unit team was administered to assess other social, occupational, and personal aspects that could be affecting the way patients were facing the situation.

2.2. Ethical considerations

Patients were interviewed on the phone after obtaining their verbal consent to participate and receiving the information regarding objectives and implications of collaborating in the study. The interviews were conducted by a female collaborator who was not implied in the interviewees’ health care. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained (CHUC_2020_36) and followed the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Data analysis design

First, descriptive statistics were presented, by showing percentage distribution in categorical variables (i.e., type of treatment, sterility time, and psychological variables), and means and standard deviations in both trait and state anxiety. Secondly, differences in psychological variables by treatment type and sterility time were calculated by performing Χ2 tests. Likewise, differences in anxiety by treatment type, sterility time, and psychological variables were calculated by means of variance analyses. For these bivariate analyses, φ and η2p were respectively presented to inform about effect size. Thirdly, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to separately explain both trait and state anxiety based on treatment type, sterility time, and psychological variables. Standardized coefficients and R2 were presented. These analyses were performed using SPSS 21.

3. Results

A total of 156 assisted reproduction patients were invited to participate in this study, where 115 of them finally accepted to reply to the questionnaire (73.7%). The age of the sample ranged from ages 27 to 42, with an average of 34.84 (SD = 4.13). Participants received one of three different treatments: IVF-ICSI (n = 56, 48.7%), FET (n = 44, 38.3%), or AI (n = 15, 13%). Regarding sterility time, most of the sample had less than five years (83.5%), while some participants reported more than five years (15.5% 5-10 years, 1% more than 11 years).

Table 1 presents the frequency distribution of the variables regarding the psychological responses to treatment during the pandemic. When participants were told that they had to postpone the treatment, most of them felt sad (54.1%) or frustrated (32.7). However, most of them experienced it with acceptance (65.2%) or tranquility (26.1%). Concerning age pressure, 32.2% of the sample felt moderate pressure and 26.1% felt a lot or quite a lot of pressure. Furthermore, 37.7% of participants felt moderate worry about pregnancy during the pandemic, and 18.4% felt even higher worry. When women were asked about the coping against a setback, most of them reported that they would take the good advice of the professionals (75.7%). Finally, concerning anxiety levels, if scores in trait and state anxiety could range from 0 to 60, results showed a mean in trait anxiety of 17.79 (SD = 8.80), and a mean in state anxiety of 19.95 (SD = 9.08).

In general, the whole sample shows relatively low values of both state anxiety and trait anxiety, none of them reaching the 0.5 quantile median. However, it is noteworthy the high standard deviation in both dimensions. Analyzing the anxiety level per treatment type, a significant interaction is found between the type of anxiety and the type of treatment (F(2.112)=9.02; p<0.001; η

p2=0.139). Post hoc tests reveal that in both measurements, FET patients show significantly lower levels with respect to IVF/ICSI or AI patients (p<0.001), besides being the only group of patients who do not show significant differences between trait and state anxiety of the studied period, as illustrated by

Table 2.

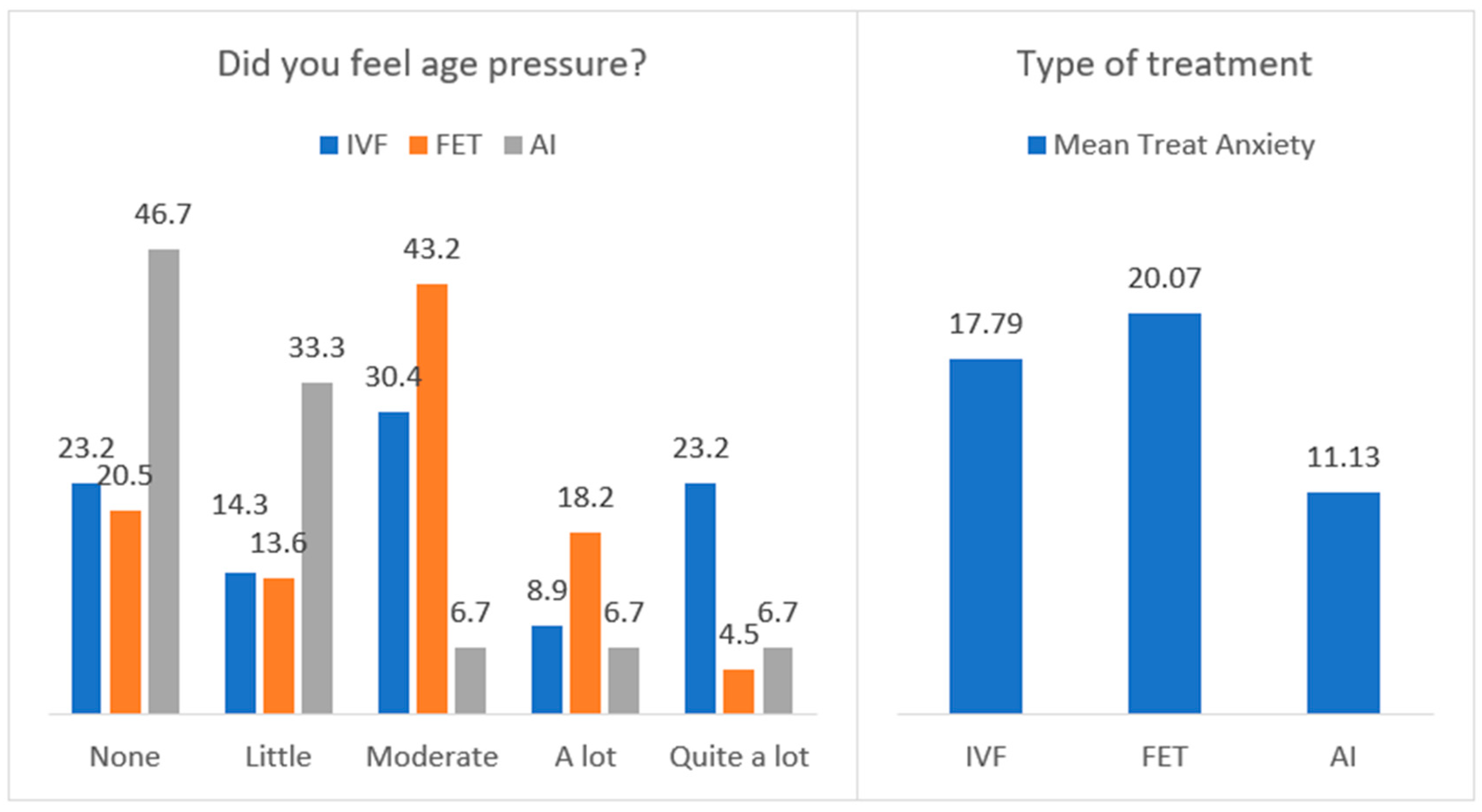

Figure 1 shows percentage distribution in age pressure and means in trait anxiety, by the type of treatment. More age pressure was reported by participants with IVF-ICSI treatment, while less pressure was felt by those with AI treatment, Χ

2(8) = 19.91, p = .011, φ = .416. Moreover, more trait anxiety was presented by participants in FET and IVF-ICSI treatments, F(2, 112) = 6.30, p = .003, η

2p = .101. No differences were detected in state anxiety, F(2, 111) = 1.85, p = .162, neither with regards to sterility time.

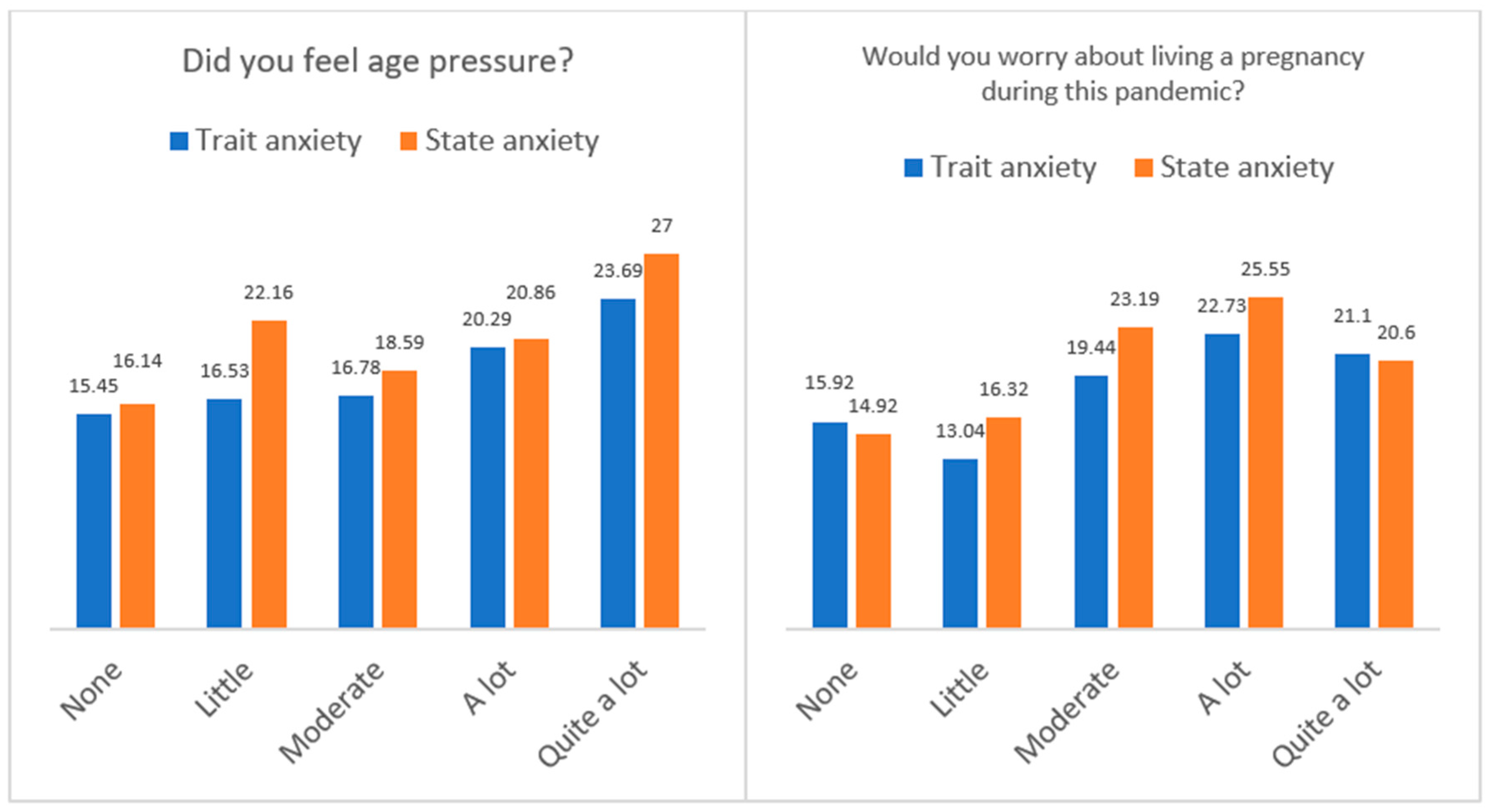

Figure 2 presents the means in trait and state anxiety by the age pressure and the worry about living a pregnancy during the pandemic. The results indicated that participants who reported

quite a lot of age pressure presented more trait anxiety, F(4, 110) = 3.01, p = .021, η

2p = .099, and more state anxiety, F(4, 109) = 4.58, p = .002, η

2p = .144. Furthermore, those participants who felt

a lot of worry about living a pregnancy during the pandemic showed more trait anxiety, F(4, 109) = 4.09, p = .004, η

2p = .130, and more state anxiety, F(4, 108) = 6.37, p < .001, η

2p = .191. No differences in anxiety were observed by the other psychological variables.

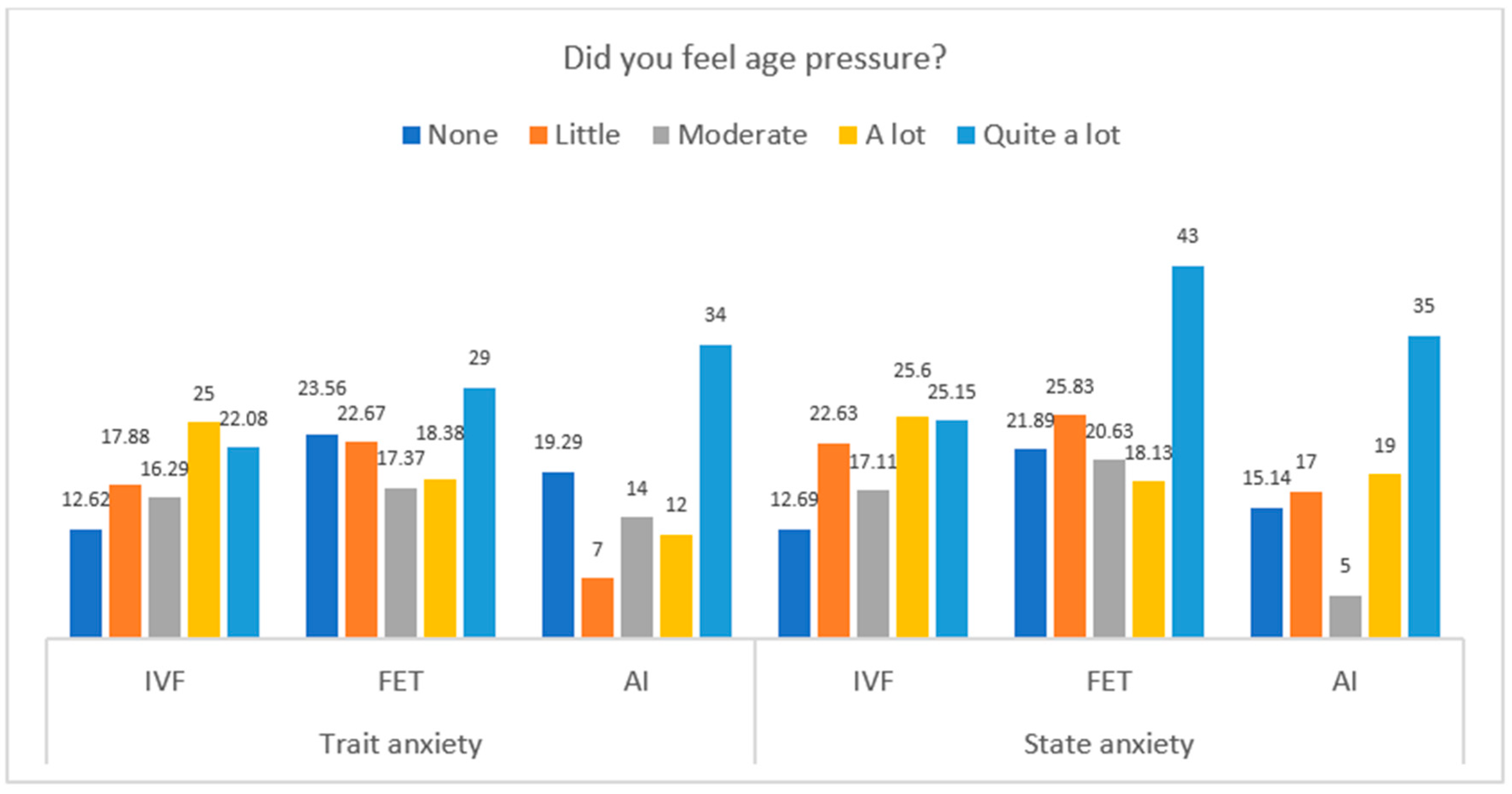

Furthermore,

Figure 3 shows differences in trait and state anxiety by the type of treatment and the level of age pressure. In trait anxiety, significant differences were observed in the groups of IVF-ICSI, F(4, 51) = 3.76, p = .009, η

2p = .228, and AI treatments, F(4, 10) = 4.35, p = .027, η

2p = .635, so that more trait anxiety were found in participants with

quite a lot of age pressure. Moreover, with regards to state anxiety, the differences only reached significance in the group of treatment by IVF-ICSI, F(4, 51) = 5.32, p = .001.

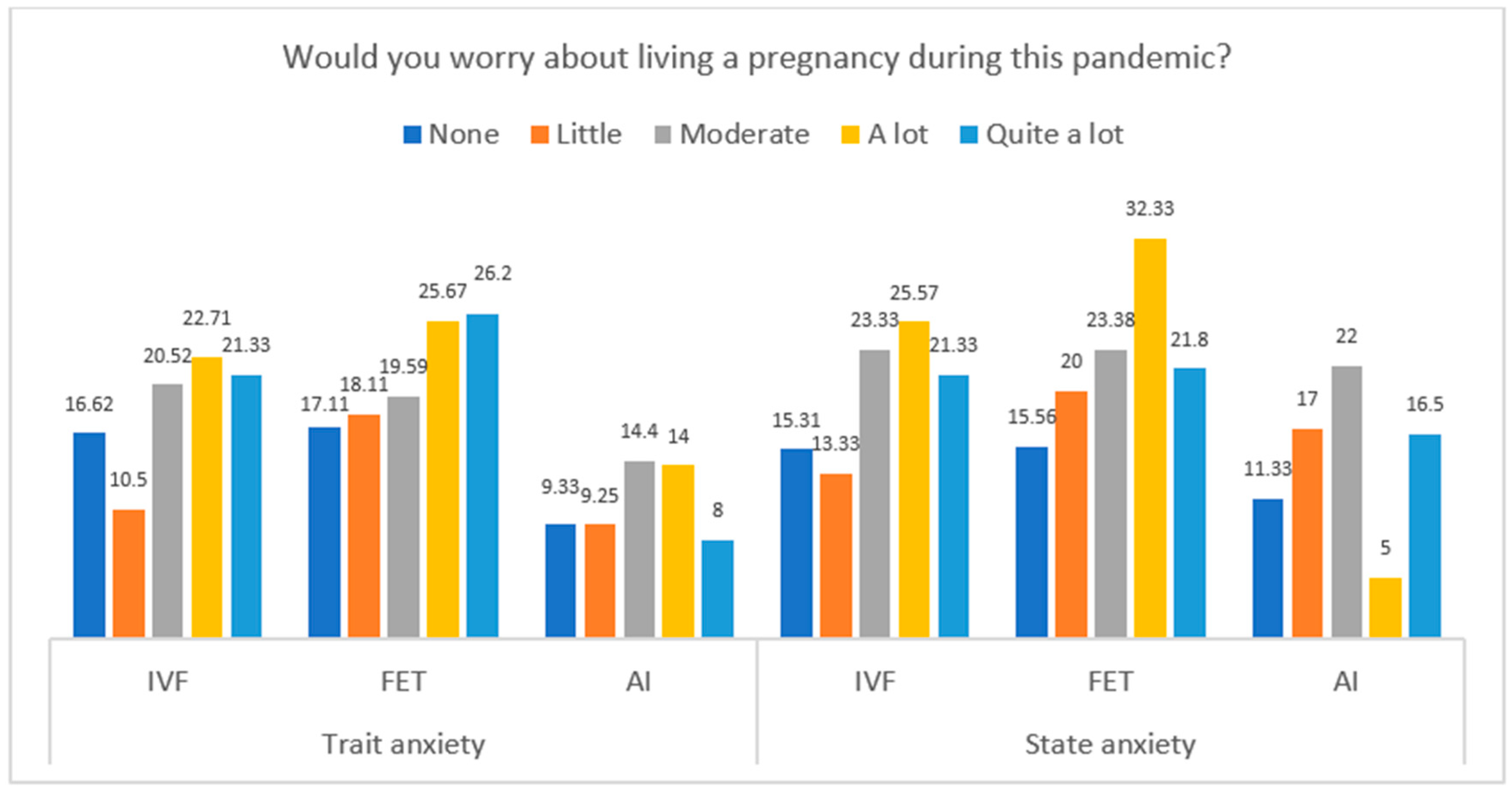

Figure 4 presents the differences in trait and state anxiety by the type of treatment and the level of worry about living a pregnancy during the pandemic. Differences in trait anxiety were only detected in the group of IVF-ICSI treatment, F(4. 51) = 4.53, p = .003, η

2p = .262, with higher anxiety in participants with higher worry. Moreover, differences in state anxiety by the levels of worry were found in the groups of IVF-ICSI treatment, F(4 51) = 4.70, p = .003, η

2p = .269, and FET, F(4, 37) = 2.69, p = .046, η

2p = .225.

Multivariate analyses

Table 3 describes the results of two hierarchical regression models to explain state and trait anxiety based on treatment type, sterility time and psychological variables. Results indicated that neither treatment nor sterility time were significant predictors of anxiety (both trait and state) when psychological variables were included in the regression equation. Thus, only age pressure and worry about pregnancy during pandemic had positive effects on trait and state anxiety, reaching explained variance over 20%. In line with previous results, more age pressure and more worry were associated with more trait and state anxiety.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the emotional distress caused by the health measures adopted during the confinement in women who were waiting for their assisted reproduction treatments, and these were cancelled, as well as to evaluate the associated variables.

Mean of STAI questionnaire in our study was lower than those of previous researchers [

6]. Low levels of both trait and state anxiety may be related with the fact that the incidence of the pandemic in the Canary Islands was among the lowest in the country. However, similar values are observed in women when the type of fertility treatment is IVF-ICSI. Both state and trait anxiety were affected in the dimension being pregnant during the COVID pandemic [

6].

With respect to fertility treatments, women of the IVF group showed more anxiety than those in the artificial insemination treatment group, what could be explained by age pressure and the ovarian reserve [

6,

13,

14]. In line with this, they showed more trait anxiety, though no differences were observed with respect to state anxiety or related to the time of infertility. Therefore, neither the type of treatment nor the time of infertility are predictors of span of trait and state anxiety, something that other studies highlighted as influencing factors [

6,

15].

Those women showing a greater concern about getting pregnant during the pandemic developed a higher level of state-trait anxiety. There were no differences in the resto f psychological variables, in line with the results of the study by Haham et al [

16]. Whereas in this study the most common emotional reactions to the suspension of treatment were sadness and y anxiety, in the study by Qu et al.[

10] was fear, and in our case, sadness and frustration.

To the emotional distress involved in fertility treatments it is necessary to add the one experienced during the containment measures introduced on the COVID-19 pandemic [

17]. According to the study by Turocy et al., the COVID-19 pandemic affected to 85% of participants, who were moderately to extremely distressed by their fertility cycle cancellation [

18] regardless the type of treatment. Nearly a quarter of participants found the delay to be as distressing as the loss of a child. Only a third agreed with the treatment cancellation and more than half would prefer to continue despite the risk posed by the pandemic. Notwithstanding, most of them accepted the situation. These findings are in line with the results found in our study and other [

6,

15,

16,

19]. We agree with the information available in other studies which pointed out that interruptions or delays of fertility treatments may cause a negative impact in the anxiety experienced by women who saw their maternity compromised [

6,

10,

13,

20,

21]. For this very reason, having the embryos frozen could be a safe haven asset for situations like the ones experienced during the pandemic.

The advice and information received by the professionals involved in assisted reproductive therapies are essential to cope with the situation of stress generated [

15]. This situation was aggravated in the confinement during the pandemic, where the need for follow-up and information provided to patients increased significantly. As illustrated by the participants in this study, 7 out of 10 reported relying on healthcare professionals to manage the situation. The information provided by healthcare professionals is of great value in fertility treatments, and it has been especially relevant in the pandemic situation experienced by the participants in this study. This has been corroborated by other studies such as the one by Lawson et al., which indicated that supplemental education increased the acceptance of the recommendations, though the stress caused by the situations experienced was not reduced [

15]. As in previous studies, the use of telemedicine seems to help to reduce both stress and anxiety experienced [

22]. Therefore, in situations of pandemic, it may be a good approach to keep providing the best care services.

Among the limitations of this study, we could identify the fact that it lacks the participants’ anxiety baseline condition records which may allow to identify their initial situation before the pandemic restrictions. Besides, it is not possible to identify if the values are exclusively associated to the fertility treatments or to all the situation experienced regarding the pandemic, as other studies pointed out [

23]. There are no records of the patients’ anxiety or mental health disorders prior to the pandemic.

5. Conclusions

Suspension of fertility treatments due to confinement measures had a negative impact on the mental health of women who were in the process of receiving an assisted reproduction treatment, increasing their levels of emotional distress and anxiety. Age pressure and being pregnant during the pandemic influenced the levels of state-trait anxiety experienced, and therefore it would be necessary to establish certain strategies which allow to keep the greatest number possible of services associated to the assisted reproductive techniques in order to reduce the impact on the mental health of patients of fertility treatments, as well as planning a specific network of psychological support in situations where services are either suspended or delayed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation: M.C.R. and D.B.Q.; methodology, M.C.R., D.B.Q.; software, D.G.B; formal analysis D.G.B.; investigation, M.C.R., E.S.C., Y.S.H., J.C.L.; data curation, D.G.B., F.L.L.; writing—original draft preparation M.C.R, D.B.Q., F.L.L.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; supervision, MCR and DBQ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Universitario de Canarias (CHUC_2020_36).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

we would like to thank Stephy Hess for her support on data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Fecundidad. 2018. (Consultado el 01/08/2023.) Disponible en. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/ef_2018_d.pdf.

- Zamora Pascual E. Aplicación, evaluación y valoración de un Programa de Intervención. Psicológica en parejas que acuden a una Unidad de Reproducción Humana asistida. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de La Laguna; 2016.

- Klonoff-Cohen H, Chu E, Natarajan L, Sieber W. A prospective study of stress among women undergoing in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 2001, 76, 675–687. [CrossRef]

- Slade P, O'Neill C, Simpson AJ, Lashen H. The relationship between perceived stigma, disclosure patterns, support and distress in new attendees at an infertility clinic. Hum Reprod. 2007, 22, 2309–2317. [CrossRef]

- Gordon JL, Balsom AA. The psychological impact of fertility treatment suspensions during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0239253. [CrossRef]

- Esposito V, Rania E, Lico D, et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological status of infertile couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020, 253, 148–153. [CrossRef]

- Legro, R. The COVID-19 pandemic and reproductive health. Fertility and Sterility 2021, 115, 811–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson AK. Psychological stress and fertility. In: Stevenson EL, Hershberger PE, editors. Fertility and Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART): Theory, Research, Policy and Practice For Healthcare Practitioners. 7th ed. New York City: Springer Publishing Company; 2016. p. 65–86.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1729. [CrossRef]

- Qu P, Zhao D, Jia P, Dang S, Shi W, Wang M, Shi J. Changes in Mental Health of Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technology Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak in Xi'an, China. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 645421. [CrossRef]

- Spieberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto.1983.

- Muñiz Fernández J, Fernández Hermida JR. La opinión de los psicólogos españoles sobre el uso de los tests. Papeles del psicólogo: revista del Colegio Oficial de Psicólogos. 2010.

- Tokgoz VY, Kaya Y, Tekin AB. The level of anxiety in infertile women whose ART cycles are postponed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2022, 43, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Lablanche O, Salle B, Perie MA, Labrune E, Langlois-Jacques C, Fraison E. Psychological effect of COVID-19 pandemic among women undergoing infertility care, a French cohort - PsyCovART Psychological effect of COVID-19: PsyCovART. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022, 51, 102251. [CrossRef]

- Lawson AK, McQueen DB, Swanson AC, Confino R, Feinberg EC, Pavone ME. Psychological distress and postponed fertility care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021, 38, 333–341. [CrossRef]

- Marom Haham L, Youngster M, Kuperman Shani A, Yee S, Ben-Kimhy R, Medina-Artom TR, Hourvitz A, Kedem A, Librach C. Suspension of fertility treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: views, emotional reactions and psychological distress among women undergoing fertility treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021, 42, 849–858. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan DA, Shah JS, Penzias AS, Domar AD, Toth TL. Infertility remains a top stressor despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020, 41, 425–427. [CrossRef]

- Turocy JM, Robles A, Hercz D, D'Alton M, Forman EJ, Williams Z. The emotional impact of the ASRM guidelines on fertility patients during the COVID-19 pandemi. Fertility and sterility 2020, 114, e63. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Kimhy R, Youngster M, Medina-Artom TR, et al. Fertility patients under COVID-19: attitudes, perceptions and psychological reactions. Hum Reprod. 2020, 35, 2774–2783. [CrossRef]

- Muhaidat N, Alshrouf MA, Karam AM, Elfalah M. Infertility Management Disruption During the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Middle-Income Country: Patients' Choices, Attitudes, and Concerns. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021, 15, 2279–2288. [CrossRef]

- Cirillo M, Rizzello F, Badolato L, et al. The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and emotional state in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology: Results of an Italian survey. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021, 50, 102079. [CrossRef]

- Bernard AL, Barbour AK, Meernik C, Madeira JL, Lindheim SR, Goodman LR. The impact of an interactive multimedia educational platform on patient comprehension and anxiety during fertility treatment: a randomized controlled trial. F&S Reports 2022, 3, 214–222.

- Biviá-Roig G, Boldó-Roda A, Blasco-Sanz R, Serrano-Raya L, DelaFuente-Díez E, Múzquiz-Barberá P, Lisón JF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles and quality of life of women with fertility problems: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9, 686115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).