Submitted:

18 August 2023

Posted:

21 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

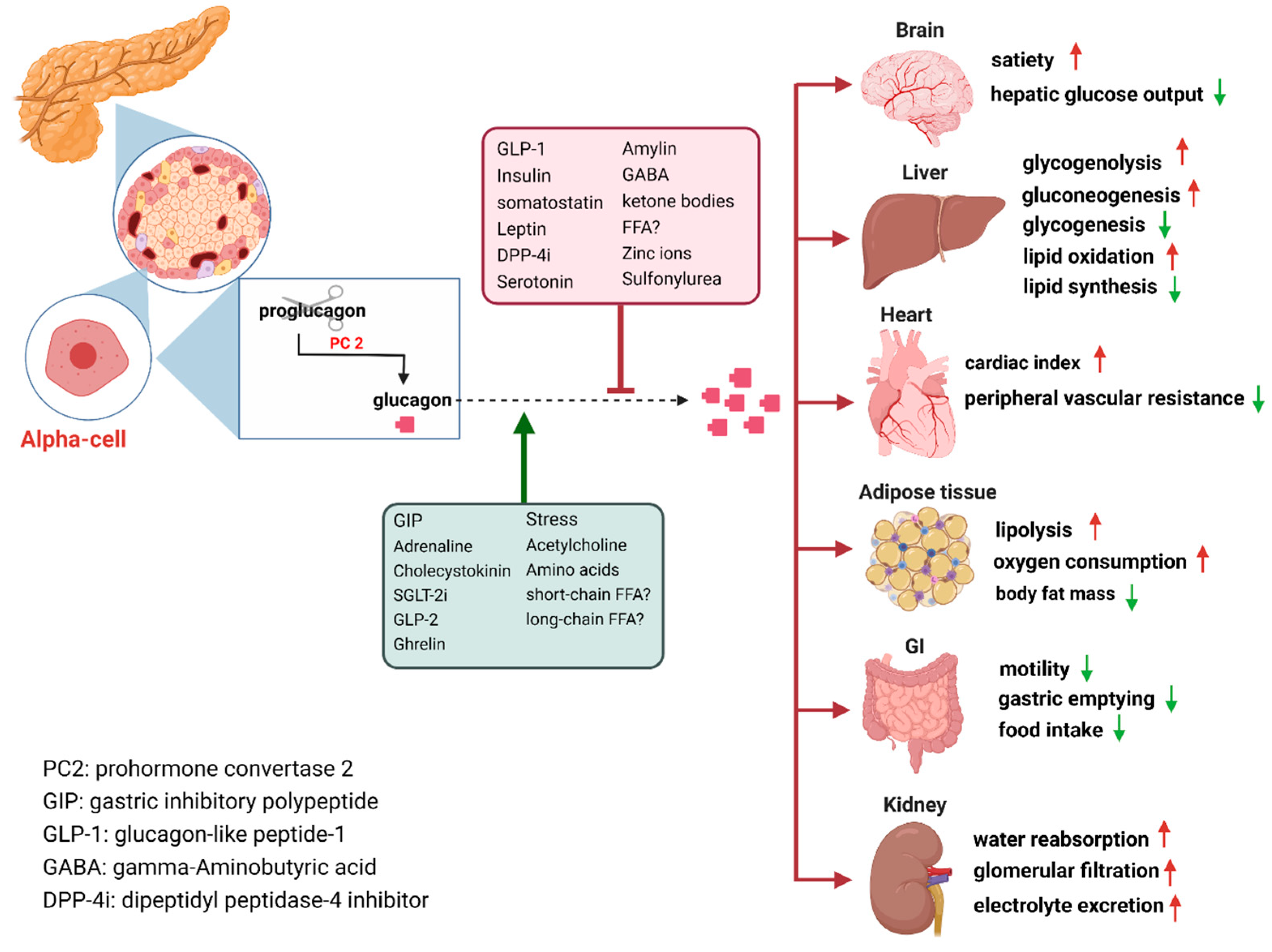

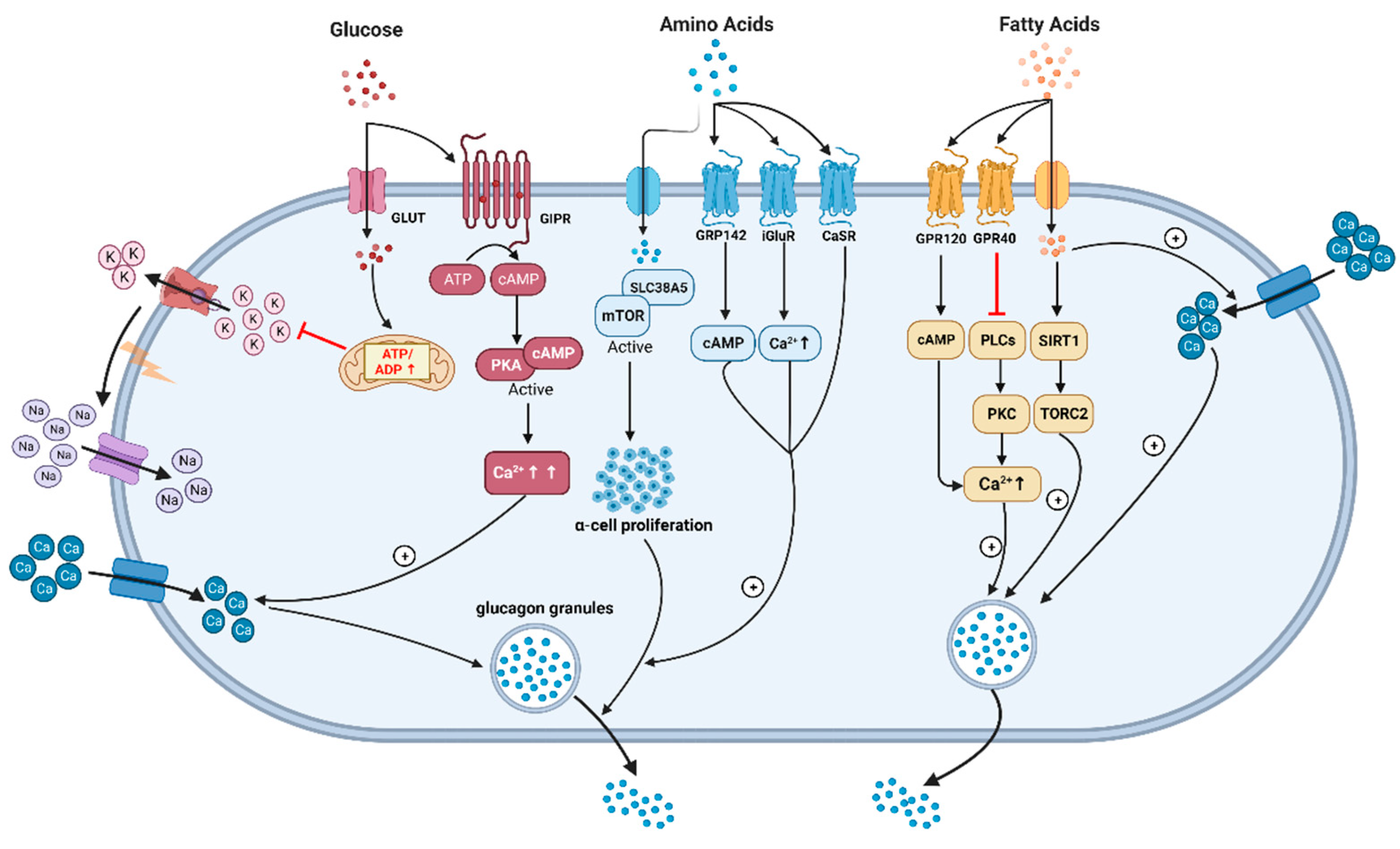

2. Glucagon Actions and Regulation

How Are GCGRs Regulated?

3. Glucagon and Glucose Metabolism

What Are the Explanations for This Difference (oral vs i.v Glucose)?

How Does Hypoglycemia Stimulate Glucagon Secretion?

4. Glucagon and Amino Acid Metabolism

5. Glucagon and Lipid Metabolism

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glucagon-Molecular Physiology, Clinical and therapeutic.pdf.

- Murlin, J.R.; Clough, H.D.; Gibbs, C.B.F.; Stokes, A.M. Aqueous Extracts of Pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 1923, 56, 253–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, E.W.; de Duve, C. Origin and Distribution of the Hyperglycemic-Glycogenolytic Factor of the Pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 175, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Ebitani, I.; Tominaga, M.; Yamatani, K.; Yawata, Y.; Hara, M. Glucagon-like substance in the canine brain. Endocrinol. Jpn. 1980, 27 (Suppl. 1), 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, C.B.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, R.; Regev, A.; Shankar, S.; Garhyan, P.; et al. Treatment with LY2409021, a glucagon receptor antagonist, increases liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Pettus, J.H.; D’Alessio, D.; Frias, J.P.; Vajda, E.G.; Pipkin, J.D.; Rosenstock, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the Glucagon Receptor Antagonist RVT-1502 in Type 2 Diabetes Uncontrolled on Metformin Monotherapy: A 12-Week Dose-Ranging Study. Diabetes Care. 2020, 43, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kazierad, D.J.; Chidsey, K.; Somayaji, V.R.; Bergman, A.J.; Calle, R.A. Efficacy and safety of the glucagon receptor antagonist PF-06291874: A 12-week, randomized, dose-response study in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on background metformin therapy. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2608–2616. [Google Scholar]

- Bossart, M.; Wagner, M.; Elvert, R.; Evers, A.; Hubschle, T.; Kloeckener, T.; et al. Effects on weight loss and glycemic control with SAR441255, a potent unimolecular peptide GLP-1/GIP/GCG receptor triagonist. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Finan, B.; Capozzi, M.E.; Campbell, J.E. Repositioning Glucagon Action in the Physiology and Pharmacology of Diabetes. Diabetes. 2020, 69, 532–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, J.; Wysham, C.; Frias, J.P.; Kaneko, S.; Lee, C.J.; Fernandez Lando, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): A double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sucher, S.; Markova, M.; Hornemann, S.; Pivovarova, O.; Rudovich, N.; Thomann, R.; et al. Comparison of the effects of diets high in animal or plant protein on metabolic and cardiovascular markers in type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 944–952. [Google Scholar]

- Markova, M.; Pivovarova, O.; Hornemann, S.; Sucher, S.; Frahnow, T.; Wegner, K.; et al. Isocaloric Diets High in Animal or Plant Protein Reduce Liver Fat and Inflammation in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, R.H.; Orci, L. Paracrinology of islets and the paracrinopathy of diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16009–16012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwin, R.; Felig, P. Glucagon physiology in health and disease. Int. Rev. Physiol. 1977, 16, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Capozzi, M.E.; Wait, J.B.; Koech, J.; Gordon, A.N.; Coch, R.W.; Svendsen, B.; et al. Glucagon lowers glycemia when beta-cells are active. JCI Insight. 2019, 4, e129954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.L.; Carleton, J.L.; Whitney, G.; Whitehorn, J.C. Effect of glucagon on food intake and body weight in man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1957, 11, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billington, D.C. Angiogenesis and its inhibition: Potential new therapies in oncology and non-neoplastic diseases. Drug Des. Discov. 1991, 8, 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- <Individual, but not simultaneous, glucagon and cholecystokinin infusions inhibit feeding in men.pdf>.

- Bouscarel B, Kroll SD, and Fromm, H. Signal transduction and hepatocellular bile acid transport: Cross talk between bile acids and second messengers. Gastroenterology 1999, 117, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 20. Holst JJ, Knop FK, Vilsboll T, Krarup T, and Madsbad, S. Loss of incretin effect is a specific, important, and early characteristic of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34 (Suppl. 2), S251–S257. [CrossRef]

- Gromada, J.; Franklin, I.; Wollheim, C.B. Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 84–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- <Somatostatin and diabetes.pdf>.

- Meier, J.J.; Nauck, M.A.; Pott, A.; Heinze, K.; Goetze, O.; Bulut, K.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 2 stimulates glucagon secretion, enhances lipid absorption, and inhibits gastric acid secretion in humans. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habegger, K.M.; Heppner, K.M.; Geary, N.; Bartness, T.J.; DiMarchi, R.; Tschop, M.H. The metabolic actions of glucagon revisited. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010, 6, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnanan, C.J.; Edgerton, D.S.; Kraft, G.; Cherrington, A.D. Physiologic action of glucagon on liver glucose metabolism. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13 (Suppl. 1), 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.J.; Zhang, D.; Guerra, M.T.; Brill, A.L.; Goedeke, L.; Nasiri, A.R.; et al. Glucagon stimulates gluconeogenesis by INSP3R1-mediated hepatic lipolysis. Nature 2020, 579, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.E.; Drucker, D.J. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P.; Wang, Q. Insulin as a physiological modulator of glucagon secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E751–E761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscar, T.P. Down-regulation of glucagon receptors on the surface of broiler adipocytes. Poult. Sci. 1996, 75, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohout, T.A.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Krilov, L.; Meng, J.; Patel, B.; Chapin-Kennedy, K.; Bouscarel, B. Decreased glucagon responsiveness by bile acids: A role for protein kinase Calpha and glucagon receptor phosphorylation. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5294–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibiger, B.; Moede, T.; Muhandiramlage, T.P.; Kaiser, D.; Vaca Sanchez, P.; Leibiger, I.B.; et al. Glucagon regulates its own synthesis by autocrine signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20925–20930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriod, C.N.; Oliveira, A.G.; Guerra, M.T.; Nguyen, L.; Richards, K.M.; Jurczak, M.J.; et al. Hepatic Inositol 1,4,5 Trisphosphate Receptor Type 1 Mediates Fatty Liver. Hepatol. Commun. 2017, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Goode, J.; Paz, J.C.; Ouyang, K.; Screaton, R.; et al. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis in fasting and diabetes. Nature 2012, 485, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhang, B.B. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 284, E671–E678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokal, J.E. Effect of glucagon on gluconeogenesis by the isolated perfused rat liver. Endocrinology 1966, 78, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerich, J.E.; Lorenzi, M.; Bier, D.M.; Tsalikian, E.; Schneider, V.; Karam, J.H.; et al. Effects of physiologic levels of glucagon and growth hormone on human carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Studies involving administration of exogenous hormone during suppression of endogenous hormone secretion with somatostatin. J. Clin. Investig. 1976, 57, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecavalier, L.; Bolli, G.; Gerich, J. Glucagon-cortisol interactions on glucose turnover and lactate gluconeogenesis in normal humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1990, 258, E569–E575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marliss, E.B.; Aoki, T.T.; Unger, R.H.; Soeldner, J.S.; Cahill, G.F., Jr. Glucagon levels and metabolic effects in fasting man. J. Clin. Invest. 1970, 49, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, S.; Menge, B.A.; Gruber, L.; Deacon, C.F.; Schmidt, W.E.; Veldhuis, J.D.; et al. Impaired crosstalk between pulsatile insulin and glucagon secretion in prediabetic individuals. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E791–E795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, B.A.; Gruber, L.; Jorgensen, S.M.; Deacon, C.F.; Schmidt, W.E.; Veldhuis, J.D.; et al. Loss of inverse relationship between pulsatile insulin and glucagon secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.J.; Kjems, L.L.; Veldhuis, J.D.; Lefebvre, P.; Butler, P.C. Postprandial suppression of glucagon secretion depends on intact pulsatile insulin secretion: Further evidence for the intraislet insulin hypothesis. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demant, M.; Bagger, J.I.; Suppli, M.P.; Lund, A.; Gyldenlove, M.; Hansen, K.B.; et al. Determinants of Fasting Hyperglucagonemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Nondiabetic Control Subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2018, 16, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Wang, M.-Y.; Yu, X.-X.; Unger, R.H. Glucagon is the key factor in the development of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2016, 59, 1372–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, R.H.; Orci, L. The essential role of glucagon in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1975, 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reaven, G.M.; Chen, Y.D.; Golay, A.; Swislocki, A.L.; Jaspan, J.B. Documentation of hyperglucagonemia throughout the day in nonobese and obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1987, 64, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskin, P.; Unger, R.H. Hyperglucagonemia and its suppression. Importance in the metabolic control of diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978, 299, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrakou, A.; Kelley, D.; Mokan, M.; Veneman, T.; Pangburn, T.; Reilly, J.; et al. Role of reduced suppression of glucose production and diminished early insulin release in impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipp, E. Impaired glucose tolerance: The irrepressible alpha-cell? Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 569–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonne, D.P.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F.K. Postprandial gallbladder emptying in patients with type 2 diabetes: Potential implications for bile-induced secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 171, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Vella, A.; Basu, A.; Basu, R.; Schwenk, W.F.; Rizza, R.A. Lack of suppression of glucagon contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 4053–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knop, F.K.; Vilsboll, T.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Krarup, T. Inappropriate suppression of glucagon during OGTT but not during isoglycaemic i.v. glucose infusion contributes to the reduced incretin effect in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.J.; Deacon, C.F.; Schmidt, W.E.; Holst, J.J.; Nauck, M.A. Suppression of glucagon secretion is lower after oral glucose administration than during intravenous glucose administration in human subjects. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagger, J.I.; Knop, F.K.; Lund, A.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsboll, T. Glucagon responses to increasing oral loads of glucose and corresponding isoglycaemic intravenous glucose infusions in patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1720–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagger, J.I.; Knop, F.K.; Lund, A.; Vestergaard, H.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsboll, T. Impaired regulation of the incretin effect in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, H.L.; Theander, S.; Bokvist, K.; Buschard, K.; Wollheim, C.B.; Gromada, J. Glucose stimulates glucagon release in single rat alpha-cells by mechanisms that mirror the stimulus-secretion coupling in beta-cells. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4861–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar-Hmeadi, M.; Lund, P.E.; Gandasi, N.R.; Tengholm, A.; Barg, S. Paracrine control of alpha-cell glucagon exocytosis is compromised in human type-2 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellard, J.A.; Rorsman, N.J.G.; Hill, T.G.; Armour, S.L.; van de Bunt, M.; Rorsman, P.; et al. Reduced somatostatin signalling leads to hypersecretion of glucagon in mice fed a high-fat diet. Mol. Metab. 2020, 40, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergari, E.; Knudsen, J.G.; Ramracheya, R.; Salehi, A.; Zhang, Q.; Adam, J.; et al. Insulin inhibits glucagon release by SGLT2-induced stimulation of somatostatin secretion. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Shuai, H.; Ahooghalandari, P.; Gylfe, E.; Tengholm, A. Glucose controls glucagon secretion by directly modulating cAMP in alpha cells. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaca, J.; Molina, J.; Menegaz, D.; Pronin, A.N.; Tamayo, A.; Slepak, V.; et al. Human Beta Cells Produce and Release Serotonin to Inhibit Glucagon Secretion from Alpha Cells. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 3281–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.G.; Hamilton, A.; Ramracheya, R.; Tarasov, A.I.; Brereton, M.; Haythorne, E.; et al. Dysregulation of Glucagon Secretion by Hyperglycemia-Induced Sodium-Dependent Reduction of ATP Production. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ramracheya, R.; Lahmann, C.; Tarasov, A.; Bengtsson, M.; Braha, O.; et al. Role of KATP channels in glucose-regulated glucagon secretion and impaired counterregulation in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerich, J.E.; Tsalikian, E.; Lorenzi, M.; Schneider, V.; Bohannon, N.V.; Gustafson, G.; et al. Normalization of fasting hyperglucagonemia and excessive glucagon responses to intravenous arginine in human diabetes mellitus by prolonged infusion of insulin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1975, 41, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbusch, L.; Labouebe, G.; Thorens, B. Brain glucose sensing in homeostatic and hedonic regulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.; Moheet, A.; Seaquist, E.R. Central Mechanisms of Glucose Sensing and Counterregulation in Defense of Hypoglycemia. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: Physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Sherwin, R.S.; Hendler, R.; Felig, P. Kinetics of glucagon in man: Effects of starvation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 1735–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, A.; Berney, X.; Castillo-Armengol, J.; Tarussio, D.; Jan, M.; Sanchez-Archidona, A.R.; et al. Hypothalamic Irak4 is a genetically controlled regulator of hypoglycemia-induced glucagon secretion. Mol. Metab. 2022, 61, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strembitska, A.; Labouebe, G.; Picard, A.; Berney, X.P.; Tarussio, D.; Jan, M.; et al. Lipid biosynthesis enzyme Agpat5 in AgRP-neurons is required for insulin-induced hypoglycemia sensing and glucagon secretion. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson-Doucette, C.A.; Sultan, S.; Allister, E.M.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Koshkin, V.; Bhattacharjee, A.; et al. Beta-cell uncoupling protein 2 regulates reactive oxygen species production, which influences both insulin and glucagon secretion. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2710–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.G.; Goebel, C.U.; Hruby, V.J.; Bregman, M.D.; Trivedi, D. Hyperglycemia of diabetic rats decreased by a glucagon receptor antagonist. Science 1982, 215, 1115–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolitu, S.; Okamoto, H.; Dai, W.; Zadroga, J.A.; Wittchen, E.S.; Gromada, J.; et al. Hepatic Glucagon Signaling Regulates PCSK9 and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Cavino, K.; Na, E.; Krumm, E.; Kim, S.Y.; Cheng, X.; et al. Glucagon receptor inhibition normalizes blood glucose in severe insulin-resistant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2753–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, H.; Kim, J.; Aglione, J.; Lee, J.; Cavino, K.; Na, E.; et al. Glucagon Receptor Blockade With a Human Antibody Normalizes Blood Glucose in Diabetic Mice and Monkeys. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2781–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Pedersen, J.; Galsgaard, K.D.; Winther-Sorensen, M.; Suppli, M.P.; Janah, L.; et al. The Liver-alpha-Cell Axis and Type 2 Diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, J.H.; Smith, G.I.; Chen, S.; Unger, R.H.; Klein, S.; Scherer, P.E. Obesity dysregulates fasting-induced changes in glucagon secretion. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 243, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutel, E.; Gautier-Stein, A.; Abdul-Wahed, A.; Amigo-Correig, M.; Zitoun, C.; Stefanutti, A.; et al. Control of blood glucose in the absence of hepatic glucose production during prolonged fasting in mice: Induction of renal and intestinal gluconeogenesis by glucagon. Diabetes 2011, 60, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozadjieva, N.; Blandino-Rosano, M.; Chase, J.; Dai, X.Q.; Cummings, K.; Gimeno, J.; et al. Loss of mTORC1 signaling alters pancreatic alpha cell mass and impairs glucagon secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 4379–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozadjieva Kramer, N.; Lubaczeuski, C.; Blandino-Rosano, M.; Barker, G.; Gittes, G.K.; Caicedo, A.; et al. Glucagon Resistance and Decreased Susceptibility to Diabetes in a Model of Chronic Hyperglucagonemia. Diabetes 2021, 70, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, P.J.; Lin, R.C.; Muller, W.A.; Aoki, T.T. Induction of urea cycle enzymes of rat liver by glucagon. J. Biol. Chem. 1978, 253, 2748–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberg, O.; Vilstrup, H. Regulation of urea synthesis by glucose and glucagon in normal man. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 13, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazda, C.M.; Ding, Y.; Kelly, R.P.; Garhyan, P.; Shi, C.; Lim, C.N.; et al. Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety of the Glucagon Receptor Antagonist LY2409021 in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: 12- and 24-Week Phase 2 Studies. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilberg, M.S.; Barber, E.F.; Handlogten, M.E. Characteristics and hormonal regulation of amino acid transport system A in isolated rat hepatocytes. Curr. Top. Cell Regul. 1985, 25, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohneda, A.; Parada, E.; Eisentraut, A.M.; Unger, R.H. Characterization of response of circulating glucagon to intraduodenal and intravenous administration of amino acids. J. Clin. Invest. 1968, 47, 2305–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, E.D. A Primary Role for α-Cells as Amino Acid Sensors. Diabetes 2020, 69, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, E.D.; Unger, R.H.; Holland, W.L. Glucagon antagonism in islet cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3006–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flakoll, P.J.; Borel, M.J.; Wentzel, L.S.; Williams, P.E.; Lacy, D.B.; Abumrad, N.N. The role of glucagon in the control of protein and amino acid metabolism in vivo. Metabolism 1994, 43, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden G, Rezvani I, and Owen OE. Effects of glucagon on plasma amino acids. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Pedersen, J.; Knop, F.K. Glucagon and Amino Acids Are Linked in a Mutual Feedback Cycle: The Liver-alpha-Cell Axis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A.; Birnbaum, M.J. Glucagon: Acute actions on hepatic metabolism. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solloway, M.J.; Madjidi, A.; Gu, C.; Eastham-Anderson, J.; Clarke, H.J.; Kljavin, N.; et al. Glucagon Couples Hepatic Amino Acid Catabolism to mTOR-Dependent Regulation of alpha-Cell Mass. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankir, L.; Bouby, N.; Speth, R.C.; Velho, G.; Crambert, G. Glucagon revisited: Coordinated actions on the liver and kidney. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 146, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janah, L.; Kjeldsen, S.; Galsgaard, K.D.; Winther-Sorensen, M.; Stojanovska, E.; Pedersen, J.; et al. Glucagon Receptor Signaling and Glucagon Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, R.; Walrand, S.; Beelen, M.; Gijsen, A.P.; Kies, A.K.; Boirie, Y.; et al. Dietary protein digestion and absorption rates and the subsequent postprandial muscle protein synthetic response do not differ between young and elderly men. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1707–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahren, J.; Ekberg, K. Splanchnic regulation of glucose production. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felig, P. The glucose-alanine cycle. Metabolism 1973, 22, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, J.G.; Rusu, P.M.; Chan, A.Y.; Wu, Y.; Yap, Y.W.; Sharkie, T.; et al. Liver alanine catabolism promotes skeletal muscle atrophy and hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell, K.; Duff, D.A. The hepato-muscular metabolic axis and gluconeogenesis. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1982, 102 Pt C, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Claris-Appiani, A.; Assael, B.M.; Tirelli, A.S.; Marra, G.; Cavanna, G. Lack of glomerular hemodynamic stimulation after infusion of branched-chain amino acids. Kidney Int. 1988, 33, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winther-Sorensen, M.; Galsgaard, K.D.; Santos, A.; Trammell, S.A.J.; Sulek, K.; Kuhre, R.E.; et al. Glucagon acutely regulates hepatic amino acid catabolism and the effect may be disturbed by steatosis. Mol. Metab. 2020, 42, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Junker, A.E.; Christensen, M.; Haedersdal, S.; Wibrand, F.; Lund, A.M.; et al. Hyperglucagonemia correlates with plasma levels of non-branched-chain amino acids in patients with liver disease independent of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 314, G91–G6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pivovarova-Ramich, O.; Kabisch, S.; Markova, M.; Hornemann, S.; Sucher, S.; et al. High Protein Diets Improve Liver Fat and Insulin Sensitivity by Prandial but Not Fasting Glucagon Secretion in Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 808346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.M.; Faloona, G.R.; Unger, R.H. Glucagon-stimulating activity of 20 amino acids in dogs. J. Clin. Invest. 1972, 51, 2346–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galsgaard KD, Jepsen SL, Kjeldsen SAS, Pedersen J, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, and Holst JJ. Alanine, arginine, cysteine, and proline, but not glutamine, are substrates for, and acute mediators of, the liver-alpha-cell axis in female mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E920–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneto, A.; Kosaka, K. Effects of leucine and isoleucine infused intrapancreatically on glucagon and insulin secretion. Endocrinology 1972, 91, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, W.A.; Faloona, G.R.; Unger, R.H. The effect of alanine on glucagon secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 1971, 50, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhara, T.; Ikeda, S.; Ohneda, A.; Sasaki, Y. Effects of intravenous infusion of 17 amino acids on the secretion of GH, glucagon, and insulin in sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 260, E21–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gar, C.; Rottenkolber, M.; Prehn, C.; Adamski, J.; Seissler, J.; Lechner, A. Serum and plasma amino acids as markers of prediabetes, insulin resistance, and incident diabetes. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2018, 55, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; Lopez-Maside, L.; Donapetry-Garcia, C.; Fernandez-Fernandez, C.; Sixto-Leal, C. Enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid metabolism in humans. Amino Acids. 2017, 49, 1005–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerich, J.E.; Charles, M.A.; Grodsky, G.M. Characterization of the effects of arginine and glucose on glucagon and insulin release from the perfused rat pancreas. J. Clin. Invest. 1974, 54, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assan, R.; Attali, J.R.; Ballerio, G.; Boillot, J.; Girard, J.R. Glucagon secretion induced by natural and artificial amino acids in the perfused rat pancreas. Diabetes 1977, 26, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, K.; LeBlanc, R.E.; Loh, D.; Schwartz, G.J.; Yu, Y.H. Increasing dietary leucine intake reduces diet-induced obesity and improves glucose and cholesterol metabolism in mice via multimechanisms. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newgard, C.B.; An, J.; Bain, J.R.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Stevens, R.D.; Lien, L.F.; et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.P.; Wanders, D.; Orgeron, M.; Cortez, C.C.; Gettys, T.W. Mechanisms of increased in vivo insulin sensitivity by dietary methionine restriction in mice. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3721–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, E.D.; Li, M.; Prasad, N.; Wisniewski, S.N.; Von Deylen, A.; Spaeth, J.; et al. Interrupted Glucagon Signaling Reveals Hepatic alpha Cell Axis and Role for L-Glutamine in alpha Cell Proliferation. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1362–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostenson, C.G.; Grebing, C. Evidence for metabolic regulation of pancreatic glucagon secretion by L-glutamine. Acta Endocrinol. 1985, 108, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, E.; Kobayashi, M.; Kohno, D.; Kikuchi, O.; Suga, T.; Matsui, S.; et al. Disordered branched chain amino acid catabolism in pancreatic islets is associated with postprandial hypersecretion of glucagon in diabetic mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 97, 108811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.C.; Nuttall, J.A.; Nuttall, F.Q. The metabolic response to ingested glycine. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalogeropoulou, D.; LaFave, L.; Schweim, K.; Gannon, M.C.; Nuttall, F.Q. Lysine ingestion markedly attenuates the glucose response to ingested glucose without a change in insulin response. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsgaard, K.D.; Winther-Sørensen, M.; Ørskov, C.; Kissow, H.; Poulsen, S.S.; Vilstrup, H.; et al. Disruption of glucagon receptor signaling causes hyperaminoacidemia exposing a possible liver-alpha-cell axis. Am. J. Physiol. -Endocrinol. Metabolism. 2018, 314, E93–E103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, T.; Bruce, C.R.; Kowalski, G.M. Postprandial Aminogenic Insulin and Glucagon Secretion Can Stimulate Glucose Flux in Humans. Diabetes 2019, 68, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Fung, T.T.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Longo, V.D.; Chan, A.T.; et al. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Villasenor A, Granados O, Gonzalez-Palacios B, Tovar-Palacio C, Torre-Villalvazo I, Olivares-Garcia V; et al. Differential modulation of the functionality of white adipose tissue of obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats by the type of protein and the amount and type of fat. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonstad, S.; Stewart, K.; Oda, K.; Batech, M.; Herring, R.P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in red meat consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Three cohorts of US men and women. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, M.; Hornemann, S.; Sucher, S.; Wegner, K.; Pivovarova, O.; Rudovich, N.; et al. Rate of appearance of amino acids after a meal regulates insulin and glucagon secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegorier, J.P.; Garcia-Garcia, M.V.; Prip-Buus, C.; Duee, P.H.; Kohl, C.; Girard, J. Induction of ketogenesis and fatty acid oxidation by glucagon and cyclic AMP in cultured hepatocytes from rabbit fetuses. Evidence for a decreased sensitivity of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I to malonyl-CoA inhibition after glucagon or cyclic AMP treatment. Biochem. J. 1989, 264, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Guettet, C.; Mathe, D.; Riottot, M.; Lutton, C. Effects of chronic glucagon administration on cholesterol and bile acid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 963, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsgaard, K.D.; Pedersen, J.; Knop, F.K.; Holst, J.J.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J. Glucagon Receptor Signaling and Lipid Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahren, B. Glucagon--Early breakthroughs and recent discoveries. Peptides 2015, 67, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, M.J.; Vuguin, P.M. Lack of glucagon receptor signaling and its implications beyond glucose homeostasis. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 224, R123–R130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witters, L.A.; Trasko, C.S. Regulation of hepatic free fatty acid metabolism by glucagon and insulin. Am. J. Physiol. 1979, 237, E23–E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.A.; Tarlow, D.M.; Lane, M.D. Mechanism for acute control of fatty acid synthesis by glucagon and 3’:5’-cyclic AMP in the liver cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.W.; Ottaway, N.; Patterson, J.T.; Gelfanov, V.; Smiley, D.; Gidda, J.; et al. A new glucagon and GLP-1 co-agonist eliminates obesity in rodents. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocai, A.; Carrington, P.E.; Adams, J.R.; Wright, M.; Eiermann, G.; Zhu, L.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1/glucagon receptor dual agonism reverses obesity in mice. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2258–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, G.; Carnell, L.H. Nutritional effects of fat on carbohydrate metabolism. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 17, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerich, J.E.; Langlois, M.; Schneider, V.; Karam, J.H.; Noacco, C. Effects of alternations of plasma free fatty acid levels on pancreatic glucagon secretion in man. J. Clin. Invest. 1974, 53, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, G.; Shulman, G.I. Free fatty acids in obesity and type 2 diabetes: Defining their role in the development of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 32 (Suppl. 3), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, L.L.; Seyffert, W.A., Jr.; Unger, R.H.; Barker, B. Effect on plasma free fatty acids on plasma glucagon and serum insulin concentrations. Metabolism 1968, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.C.; Taylor, K.W. Fatty acids and the release of glucagon from isolated guinea-pig islets of Langerhans incubated in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1970, 215, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- <Effects of Alterations of Plasma Free Fatty Acid 1974.pdf>.

- Collins, S.C.; Salehi, A.; Eliasson, L.; Olofsson, C.S.; Rorsman, P. Long-term exposure of mouse pancreatic islets to oleate or palmitate results in reduced glucose-induced somatostatin and oversecretion of glucagon. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1689–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, C.S.; Salehi, A.; Gopel, S.O.; Holm, C.; Rorsman, P. Palmitate stimulation of glucagon secretion in mouse pancreatic alpha-cells results from activation of L-type calcium channels and elevation of cytoplasmic calcium. Diabetes 2004, 53, 2836–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristinsson, H.; Sargsyan, E.; Manell, H.; Smith, D.M.; Gopel, S.O.; Bergsten, P. Basal hypersecretion of glucagon and insulin from palmitate-exposed human islets depends on FFAR1 but not decreased somatostatin secretion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollheimer, L.C.; Landauer, H.C.; Troll, S.; Schweimer, J.; Wrede, C.E.; Scholmerich, J.; et al. Stimulatory short-term effects of free fatty acids on glucagon secretion at low to normal glucose concentrations. Metabolism 2004, 53, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gui, B.; Fu, R.; Ma, F.; Yu, J.; et al. Acute stimulation of glucagon secretion by linoleic acid results from GPR40 activation and [Ca2+]i increase in pancreatic islet {alpha}-cells. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 210, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, K.; Maekawa, F.; Dezaki, K.; Nakata, M.; Yashiro, T.; Yada, T. Oleic acid glucose-independently stimulates glucagon secretion by increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ via endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx in the rat islet alpha-cells. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 2496–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Abudula, R.; Chen, J.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Dyrskog, S.E.; Xiao, J.; et al. The short-term effect of fatty acids on glucagon secretion is influenced by their chain length, spatial configuration, and degree of unsaturation: Studies in vitro. Metabolism 2005, 54, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Chen, L.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Nordentoft, I.; Hermansen, K. Stevioside counteracts the alpha-cell hypersecretion caused by long-term palmitate exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 290, E416–E422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Nordentoft, I.; Hermansen, K. Fatty acid-induced effect on glucagon secretion is mediated via fatty acid oxidation. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2007, 23, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, S.; Maniscalchi, E.T.; Monello, A.; Pandini, G.; Mascali, L.G.; Rabuazzo, A.M.; et al. Palmitate affects insulin receptor phosphorylation and intracellular insulin signal in a pancreatic alpha-cell line. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 4197–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumonteil, E.; Magnan, C.; Ritz-Laser, B.; Ktorza, A.; Meda, P.; Philippe, J. Glucose regulates proinsulin and prosomatostatin but not proglucagon messenger ribonucleic acid levels in rat pancreatic islets. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremlich, S.; Bonny, C.; Waeber, G.; Thorens, B. Fatty acids decrease IDX-1 expression in rat pancreatic islets and reduce GLUT2, glucokinase, insulin, and somatostatin levels. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30261–30269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsgaard, H.; Ehses, J.A.; Hammar, E.B.; Van Lommel, L.; Quintens, R.; Martens, G.; et al. Interleukin-6 regulates pancreatic alpha-cell mass expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13163–13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, O.; Carr, R.D.; Deacon, C.F.; Holst, J.J.; Pacini, G.; Mari, A.; et al. Incretin hormone and insulin responses to oral versus intravenous lipid administration in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 2519–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raben, A.; Holst, J.J.; Madsen, J.; Astrup, A. Diurnal metabolic profiles after 14 d of an ad libitum high-starch, high-sucrose, or high-fat diet in normal-weight never-obese and postobese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandoe, M.J.; Hansen, K.B.; Windelov, J.A.; Knop, F.K.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; et al. Comparing olive oil and C4-dietary oil, a prodrug for the GPR119 agonist, 2-oleoyl glycerol, less energy intake of the latter is needed to stimulate incretin hormone secretion in overweight subjects with type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes. 2018, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandoe, M.J.; Hansen, K.B.; Hartmann, B.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Holst, J.J.; Hansen, H.S. The 2-monoacylglycerol moiety of dietary fat appears to be responsible for the fat-induced release of GLP-1 in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloth, B.; Due, A.; Larsen, T.M.; Holst, J.J.; Heding, A.; Astrup, A. The effect of a high-MUFA, low-glycaemic index diet and a low-fat diet on appetite and glucose metabolism during a 6-month weight maintenance period. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, A.; Urbano, F.; Di Mauro, S.; Scamporrino, A.; Di Pino, A.; Scicali, R.; et al. Chronic Exposure to Palmitate Impairs Insulin Signaling in an Intestinal L-cell Line: A Possible Shift from GLP-1 to Glucagon Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandoe, M.J.; Hansen, K.B.; Hartmann, B.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Holst, J.J.; Hansen, H.S. The 2-monoacylglycerol moiety of dietary fat appears to be responsible for the fat-induced release of GLP-1 in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutrition. 2015, 102, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeland, K.R.; Wilson, C.; Wolever, T.M. Adaptation of colonic fermentation and glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion with increased wheat fibre intake for 1 year in hyperinsulinaemic human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).