1. Introduction

In recent years, aggravation of the international political shutdown has had an increasing impact on the global economy, leading to the destruction of existing trade and production ties, the complication and increase in the cost of logistics of raw materials and goods, deficit and inflation. Most of these problems arose after the start of a special military operation in Ukraine, and affected economies of Russia and European countries to the greatest extent [

1]. The next danger of this kind may be a military confrontation between China and Taiwan, which will inevitably lead to an aggravation of relations between China and the United States, as well as to the involvement of other countries, if not in a direct armed conflict, then in a large-scale trade war with grave consequences for the entire world economy. The instruments of such a war are likely to be not tariff increases, similar to those initiated by the United States against China in 2018, but direct bans on the supply of products from entire industries, as was prescribed by numerous packages of sanctions against Russia in 2022.

Changing methods of trade confrontations lead to the need to develop new tools for assessing their consequences, which would also provide for the possibility of their rapid updating in a changing political environment. These tools should be based on modern methods of mathematical and computer modeling, integrate large data sets and allow them to be quickly updated. Few of the tools currently used to assess impact of trade wars meet these requirements. Most of the research devoted to this topic is theoretical in nature and uses simplified mathematical tools applied to a limited set of abstract countries [

2]. Further we will consider studies that are related to real trade confrontations and include the entire world economy with varying degrees of detail.

The Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) is one of the most well-known in the field of creating tools for assessing consequences of trade wars. Initiated in 1992, GTAP is today the standard for developing global complexes based on Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models with a shared database. Models developed within GTAP include a group of countries or the whole world, and all sectors of their economies [

3,

4]. WorldScan is the largest of the model complexes created within the framework of the GTAP project. It includes CGE models for the analysis of macroeconomic processes at the global, country, regional and sectoral levels. WorldScan considers trade in 29 groups of goods and services among 30 countries and enlarged regions. The model takes into account the relationship between supply and demand for goods and services in different countries, as well as factors affecting prices, such as substitution, transport costs and trade barriers [

5]. WorldScan is considering tariff increases on selected products and industries from a number of countries as its main tool for waging a trade war.

The Center for International Trade and Economics, in collaboration with the Institute of World Economics and Politics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, has developed a global CGE model to assess the impact of the US-China trade war. This model includes 28 individual states and the combined rest of the world, for its informational data from government statistics, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization. As part of the experimental studies, scenarios of the unilateral introduction of duties and non-tariff barriers by the United States against China and Mexico and a symmetrical response to them were considered [

6].

The KPMG-MACRO Global Model is based on the National Institute’s Global Econometric Model (NIGEM) maintained by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and used by international organizations (International Monetary Fund, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, European Central Bank and Bank of England) for research purposes. The KPMG-MACRO model includes more than 60 countries interacting in commodity, financial and labor markets [

7]. Trade confrontations in the model are also considered on the basis of the instruments of increasing import duties, in particular, between the US and China.

Despite the fact that many different models of international trade wars have been developed at the moment, there are serious gaps in this direction of research. Firstly, the increase in duties is considered as the main instrument of the trade war, and the possibility of a direct ban on the supply of products from sub-sanctioned countries is not taken into account. Secondly, the largest models are based on the CGE approach, which limits their applicability. Thirdly, in models that include a large number of countries, the specific features of many of them are not taken into account, and the focus is on the economies of the United States and China. Finally, the models developed by Western teams are not without some bias, which is confirmed by comparing their forecasts with the real consequences of the sanctions imposed against China in 2018 and against Russia in 2022, which will be discussed in detail in the Results and Discussion section.

Thus, the creation of a model of trade wars that considers Russia as a key participant in world trade confrontations and takes into account structure of its economy and trade relations remains an urgent task. Another important feature of this model is the ability to simulate direct trade restrictions on imports and exports of goods from sanctioned countries, since this tool is actively used by Western countries against Russian companies, and can be used by them against China if it is involved in a military conflict.

2. Materials and Methods

The agent-based model of trade wars developed at CEMI RAS is part of the complex of models of the socio-economic system of the Eurasian continent, presented in the work [

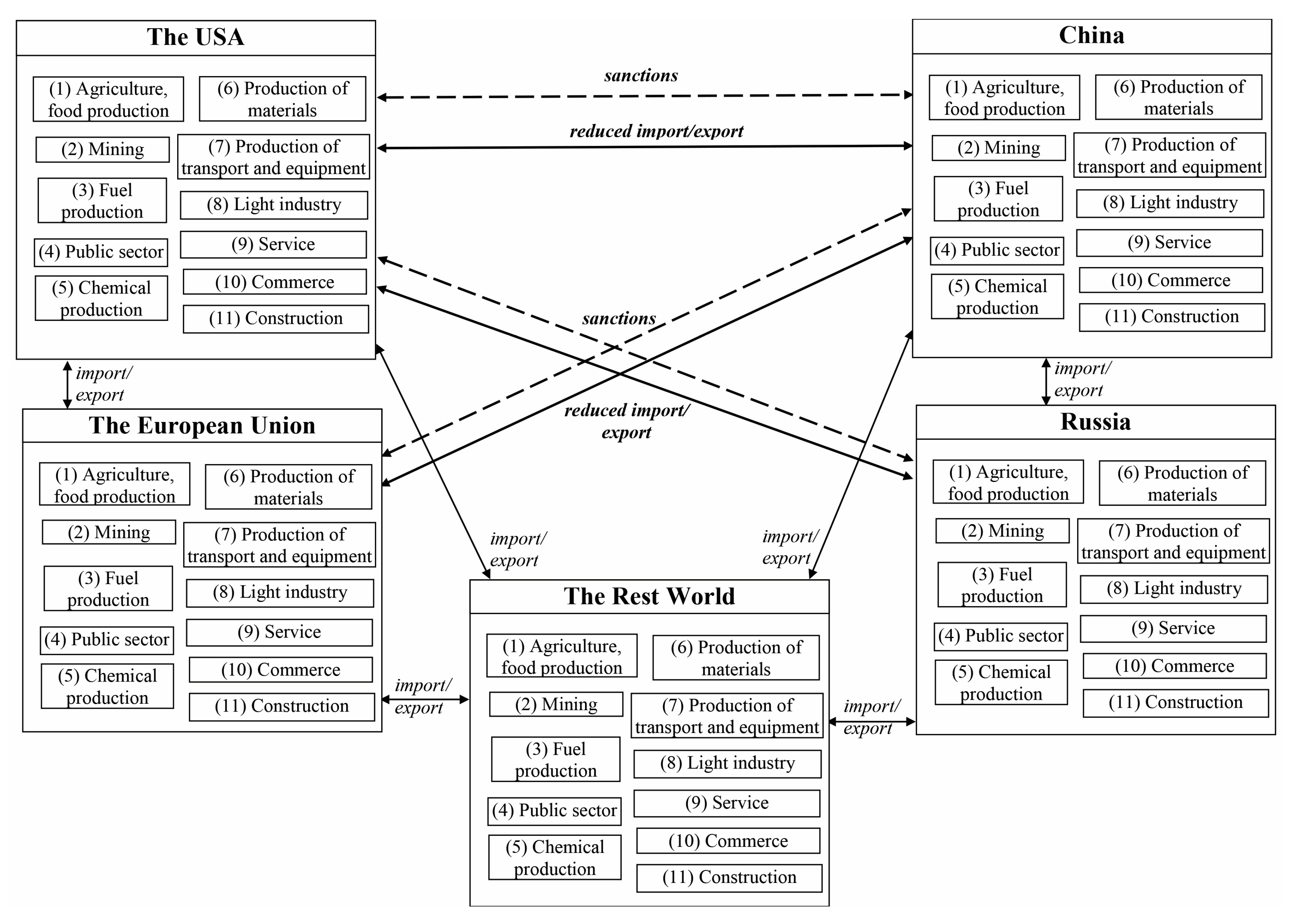

8]. In this model dynamics of trade relations among three countries (China, the USA, Russia) and two associations of countries (the European Union and the united rest world) is considered. We can divide countries in the model into three groups:

Three types of agents interact in the trade war model: organizations, states, and residents. Agents-organizations perform the functions of producers and sellers of products and services. There are 11 aggregated industries considered in the model in each country: agriculture and food production, mining, fuel production, public sector, chemical production, production of the materials, production of transport and equipment, light industry, service, commerce, construction. Each of them corresponds to one or a few industries from the national classifiers and Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) to aggregate information about production, exports and imports of the countries. Aggregated industries in each country form organizations whose products are sold to each other, to the state in which they are located, or to the final consumer.

In interaction with agents-organizations, agents-residents implement functions of consumers and employees. In the first of these roles, residents act as buyers of the final products of organizations, in the second - employees of organizations who receive wages. Residents are also taxpayers and recipients of social benefits, which determines their interaction with agents-states.

The states in the model are a type of agents that, on the one hand, participate in economic life (collect taxes and pay benefits), and on the other hand, perform political functions, in particular, they can introduce trade restrictions on export and import of certain products from non-friendly countries. Restrictions are presented as data sets:

where

S1 – country in the model,

S2 – trade partner country of

S1,

t – type of trade relation (export or import),

i – industry for which restrictions are imposed,

r – ratio of trade relation in the current period to the previous period,

y –year of imposition of the trade restriction.

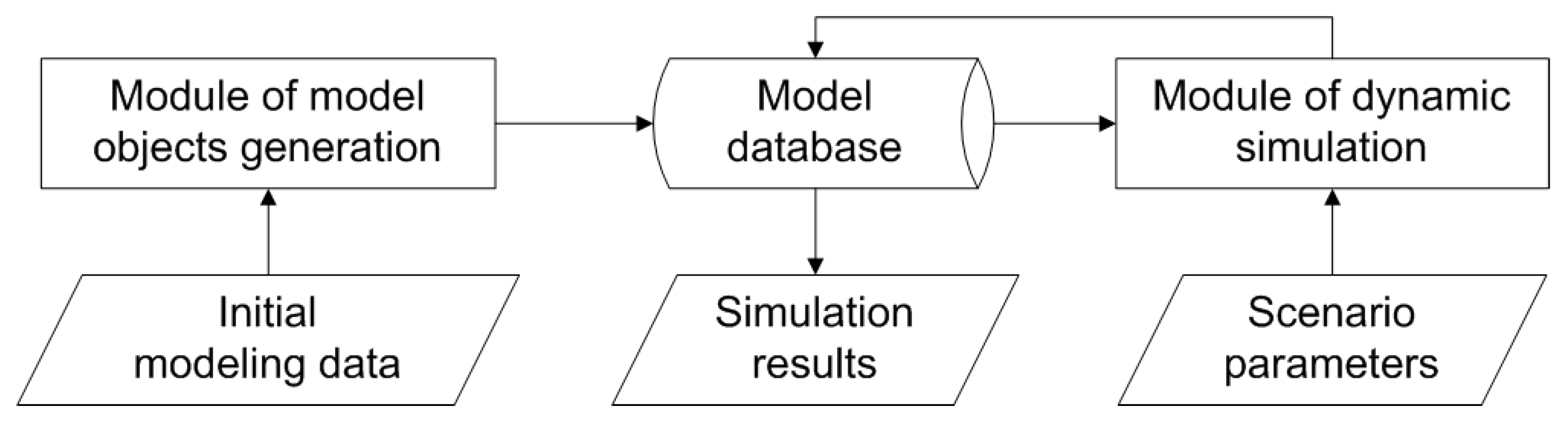

There are two main modules in the agent-based model of trade wars: model objects generation module and dynamic simulation module (

Figure 2). The model objects (agents of various types and their characteristics) are generated using initial modeling data and stored in the model database. In the dynamic simulation module interactions among generated agents are simulated. For agents-residents we simulate salary and social benefits receiving, tax payments, purchase of products and services. Agents-countries perform tax collection, social benefits payments and imposition of trade restrictions set in the scenario parameters. For agents-organizations we simulate production, supplies and sales in the current cycle and recalculate planned volume of output, redistribution of supplies and sales taking into account scenario parameters that reflect changes in economic environment and international trade. Within simulation we consider the following set of scenario parameters: exchange rates of the currencies, inflation in different countries, final demand and state expenses dynamics in different countries, sets of trade restrictions among countries in the model.

The key algorithm that determines dynamics of changes in the work of organizations is the recalculation of output and supplies algorithm. To implement it, it is necessary to assume that part of supplies of organizations is basic, and some is additional, and the volume of additional supplies is not directly related to the current volume of the organization's output. Based on this assumption, four types of supplies are considered in the model: basic intermediate, additional intermediate, basic investment and additional investment. Among the industries of the model, the so-called terminal industries stand out: agriculture and mining, in which all intermediate supplies are additional. This division allows to set the order of recalculation of supplies and sales of the organization, and avoid looping of the algorithm due to the fact that supplies of organizations of terminal industries are the last to recalculate [

9]. There are four steps in the recalculation of output and supplies algorithm:

Redistribution of non-basic supplies among sellers under the influence of sanctions. At this step trade restrictions on suppliers of investment and non-basic intermediate supplies are checked for each organization. If there are any current restrictions, supplies from unfriendly countries are reduced, and the lacking supplies are calculated:

where

– lacking volume of non-basic supply of industry

i,

– current volume of supply of industry

i;

– existing trade restriction on industry

i imports;

,

– existing trade restriction on industry

i exports.

The lacking supplies from the countries that imposed trade restrictions are replaced by supplies from neutral and friendly countries. This action affects orders of organizations that are stored in Zm variable;

- 2.

Recalculation and redistribution of basic intermediate supplies. At this step we consider supplies of raw materials and components, the shortage of which directly affects output of the organization. The required supplies are recalculated taking into account changes in final and intermediate demand:

where – estimation of organization’s demand in the next modeling cycle, –sales to organizations in the current modeling cycle, – changes in of orders from buyers set in the previous step, – sales to residents in the current modeling cycle, – expected dynamics of the final demand (scenario parameter); – sales to the state in the current modeling cycle, – expected dynamics of the state expenses (scenario parameter).

The order in which basic intermediate supplies organizations are recalculated is determined by their industry. At first, we process organizations-manufacturers and service providers, while organizations of terminal industries (agriculture and mining) are processed the last. Implementation of this order allows to take into account changes in intermediate supplies among organizations and recursively make changes in output volumes caused by changes in supplies;

- 3.

Recalculation of sales. At this step we compare orders received by organizations with their production capacities, available materials and components. Using this information, we calculate available supplies and return information about them to the buyers. Organizations are processed in the order opposite to the first step: starting from agriculture and mining, then manufacturing, trade and services;

- 4.

Adjusted recalculation of output and supplies. At this step each organization compares demand for the materials of industry i with volume of available supplies and warehouse stock of these materials:

where

– ratio of available materials of industry

i to the demand for them;

–available basic intermediate supplies of industry

i;

– stock of materials of industry

i in the warehouse of the organization;

– demand for materials of industry

i.

After evaluation of availability of all required materials the adjustment coefficient

is set as the smallest of decrease in demand and available intermediate supplies:

where K – adjustment coefficient for organization’s output; – ratio of available materials of industry i to the demand for them; – coefficient of expected demand’s dynamics.

The adjusted output is calculated as:

where – organization’s output in the next modeling cycle; – organization’s output in the current cycle; K – adjustment coefficient for organization’s output.

All these actions are repeated at each modeling cycle, at the end of modeling time the results are loaded to the model database. At the end of the simulation, access to the results of the calculations is carried out through special queries to the model database.

Agent-based model of trade wars was programmed in Microsoft Visual Studio using C# programming language and PostgreSQL database management system. Program realization of the model is considered in more details in [

10]. Initial data for generating agents and their characteristics is loaded in Excel files, containing information about countries and industries considered in the model; output, product price, fixed assets and supplies of organizations. Main information sources for gaining modeling data are official statistical agencies in Russia (Federal State Statistics Service) [

11], China (National Bureau of Statistics) [

12], the US (Bureau of Economic Analysis) [

13] and the EU (Eurostat) [

14]. As there is no data for the year 2022 presented on the website of National Bureau of Statistics, we additionally use information from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [

15]. Data for the countries considered in the model as the rest world, is taken from the World Bank website [

16].

Despite the fact that, in general, economic information for different countries is given in a similar form: structure and dynamics of GDP, imports and exports of countries, inter-industry supplies and investments of organizations, there is a problem of their unification, associated primarily with the difference between industry and customs classifiers in various countries. To solve this problem, a method was developed to bring various classifiers to a simplified industry structure of a model of 11 industries. As a result of applying this method, disparate data on production and international trade are reduced to the form of cross-country tables of industry supplies of intermediate and investment goods, which are loaded into the model as initial information on domestic, import and export supplies of organizations. This method and the resulting tables are discussed in more detail in [

1].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Estimation of accuracy of forecasts of model complexes

When assessing consequences of trade wars using the model complexes described above, two main instruments of a trade war were considered: an increase in import duties on goods from sub-sanctioned countries (including symmetrical retaliatory measures), and direct restrictions on the purchase and sale of a number of goods from sub-sanctioned countries. Most often, in calculations on model complexes, the tool for changing import duties was considered, and the change in the GDP of the countries involved in the trade war under its influence relative to the base scenario was estimated.

Table 1 presents forecasts of changes in the GDP of the USA and China in the context of a mutual increase in import duties according to the results of calculations on the WorldScan, KPMG-MACRO model complexes, the global model for assessing consequences of a trade war between the USA and China. The calculations consider different ranges of changes in trade duties, while in each calculation there is an estimate of the change in GDP with an increase in duties by 15%. This value can be used to compare how sensitive the US and Chinese economies are to changes in duties in various model complexes. The highest sensitivity is shown by the WorldScan model complex, according to calculations on which GDP of the USA and China was expected to fall by 3.1% and 4% respectively relative to the baseline scenario, with an increase in import duties by 15% [

5]. Calculations on other model complexes showed in similar conditions a change within 1% of GDP for each of the countries [

6,

8], while the results on the KPMG-MACRO model are multidirectional: a fall of 0.4% of US GDP and an increase of 0.6% of China's GDP relative to the baseline scenario [

7].

It seems appropriate to assess accuracy of the considered model complexes by comparing forecasts obtained on their basis with the real consequences of the trade war between the United States and China that began in 2018. In the process of comparison, it is necessary to evaluate three indicators: follows:

An average increase in import duties;

GDP dynamics in the baseline scenario;

GDP dynamics during the implementation of trade war measures.

The work [

2] analyzed in detail the sequence of increasing import duties on various groups of goods from China by the United States and symmetrical measures by China. For the period from January 22 to December 1, 2018, an increase in import duties on more than 1,000 goods was implemented in the range from 10% to 30%, while most of the duties increased first by 10%, and later by another 15%, that is, cumulative increase duties amounted in most cases to 25% [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

To assess the dynamics of GDP of the USA and China in the baseline scenario, retrospective data on the dynamics of the GDP of these countries were used (

Table 2). It should also be noted here that the drop in the growth rate of economies recorded in 2020 is primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and not to the effect of previously introduced sanctions.

The dynamics of GDP in the baseline scenario can be estimated as the average for the five-year (from 2013 to 2017) and two-year (from 2016 to 2017) period before the start of the trade confrontation (

Table 3). To assess the impact of increase in import duties, it is necessary to take for comparison similar two-year and five-year periods after the imposition of sanctions. In the biennium, the effect of sanctions on the US economy is estimated at +0.6% of GDP relative to the base case, for China the effect was -0.5% of GDP relative to the base case. In the five-year period, the effect of the increase in duties for the United States is not observed, for China, a drop in GDP growth rates by 2% is observed. The two-year period appears to be more significant in comparison, as China has maintained a zero-tolerance policy for COVID-19, which has led to more severe restrictions on the economy and a slowdown in GDP growth.

Based on the presented comparison with historical data, the results of the Global Model for Estimating the Consequences of the US-China Trade War, developed by the Center for International Trade and Economics and the Institute of World Economics and Politics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, proved to be the most accurate, since they show the change in US GDP as a result of the increase in duties turns out to be positive, and for China it is negative in the range of -0.7%.

Among the considered model complexes, direct restrictions on the purchase and sale of a number of goods from sub-sanctioned countries were considered only in the complex of models of the socio-economic system of the Eurasian continent (CMSESEC) and only for sanctions against Russia, therefore, as a basis for comparison, we use the results of calculations on the mentioned model complex published in [

8], the forecasts of the World Bank and Bloomberg published in the spring of 2022 after the introduction of the first packages of sanctions against Russia after the start of the special military operation in Ukraine (

Table 4).

As an assessment of the base scenario for the dynamics of the Russian economy, we take the average annual GDP growth over a 10-year period (from 2012 to 2021), which allows us to average the impact of the sanctions imposed in 2014 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the data provided by the Federal State Statistics Service (

Table 5) [

11], the average annual GDP growth in Russia is +1.5% per year, and thus the deviation of GDP from the baseline forecast in 2022 can be estimated at -3.6%.

The resulting estimate is very close to the forecast made on the basis of a set of models of the socio-economic system of the Eurasian continent with a 30% restriction on exports from Russia to the US and the EU. Given that the actual restrictions on Russian exports to Western countries amounted to about 50% on average for 2022, we can conclude that the forecasts made on the model complex two years before the imposition of sanctions are highly accurate. At the same time, the forecasts of world agencies, formed after the imposition of sanctions, turned out to be far from reality. Thus, the approach and tool proposed by the authors of the article proved to be suitable for predicting the effects of direct restrictions on international trade with individual countries.

3.2. Assessment of the dynamics of trade flows between the United States and China as a result of the increase in tariffs

The next task in the analysis of retrospective data was to assess the impact of the increase in import duties on the volume of trade between the US and China. To obtain this estimate, data on US imports and exports from China in 2017-2022 published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (

Table 6) were used [

13]. Comparison of data for different years allows us to conclude that despite the relative growth during the years of the pandemic, in general, the share of Chinese goods in total US imports and exports has been steadily declining, and for imports from China, this decrease was much more significant (by 3.7 % of total US imports) than for exports (1.2% of total US exports).

A similar calculation for China was made based on data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (

Table 7) [

15]. The fall in the share of American goods in China's imports amounted to 2.1% of the total, and the share of the United States in the export of Chinese goods decreased by 6% of the total over 5 years.

The data presented above makes it possible to obtain an estimate of the decrease in trade turnover between the United States and China relative to its possible volumes in the absence of a sanctioned increase in import duties. This estimate is based on the assumption that share of Chinese goods in US imports would have remained unchanged since 2017, when it was 18%, then in 2022 the volume of US imports from China would be $712,291 million instead of $563,923 million actually recorded, so the drop in US imports from China 5 years after the introduction of trade war measures can be estimated at 20.8%. A similar calculation for the volume of exports of American goods to China shows a drop of 15.8%.

In general, the relative estimate of the decrease in trade between country A and country B as a result of imposition of sanctions can be represented by the following formula:

where

– decrease in trade between country A and country B;

– current trade flow (import or export) of country A;

– share of country B in the trade flow of country A before imposition of sanctions;

– trade flow between country A and country B before imposition of sanctions.

Applying this formula to China's commodity flows allows us to estimate a 27.6% drop in its exports of goods to the United States, and a 23.4% drop in imports of American goods.

There may be different approaches to the question of which estimate of the change in the volume of trade (by the United States or by China) should be considered more reliable. We believe that since the sanctions were not strictly restrictive, but were of a monetary nature, the choice of goods remained with the buyer, and thus estimates of the change in trade on the part of imports are more reliable and amount to 20.8% for US imports from China and 23.4 % for Chinese imports from the US. A comparison of these estimates allows us to conclude that the imposed sanctions were quite symmetrical and reduced trade between countries by about 20% over 5 years.

Also, the data provided by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis allows to analyze the dynamics of the commodity structure of imports and exports between the US and China. As

Table 8 shows, the largest decline in US imports from China was recorded in high value-added goods: capital goods except automotive (a third decrease from pre-sanction volumes) and consumer goods except food and automotive (a quarter decrease). The decrease is less significant in materials and components (by 2.1% of total imports in this industry), and almost imperceptibly in cars and components (by 0.2%).

Despite Chinese retaliatory sanctions, food supplies from the United States, after a temporary decline in 2018-2019, increased by 40-50% compared to pre-sanction values (

Table 9). At the same time, the share of exports to China from the United States of Industrial supplies and materials, Capital goods except automotive and Automotive vehicles, parts, and engines decreased by 1-3% of the total exports in these industries.

3.3. Scenario calculations

As part of the calculations on the developed agent-based model of trade wars, four scenarios were considered: as follows:

Basic (preservation of the current sanctions regime against Russia and China);

Introduction of additional trade restrictions between China and the United States from 2023, affecting 10% of their trade turnover;

Introduction of additional trade restrictions by the US and the EU from 2024, affecting 25% of trade with China and 10% of trade with Russia, and symmetrical response measures;

A global trade war in 2024, reducing turnover between the US, the EU and China by 50% and with Russia by 25% in addition to the existing sanctions.

As the main indicator of impact of sanctions on the economies of the countries involved in the trade confrontation, deviation of the GDP predicted for each scenario from the GDP in the base scenario is considered.

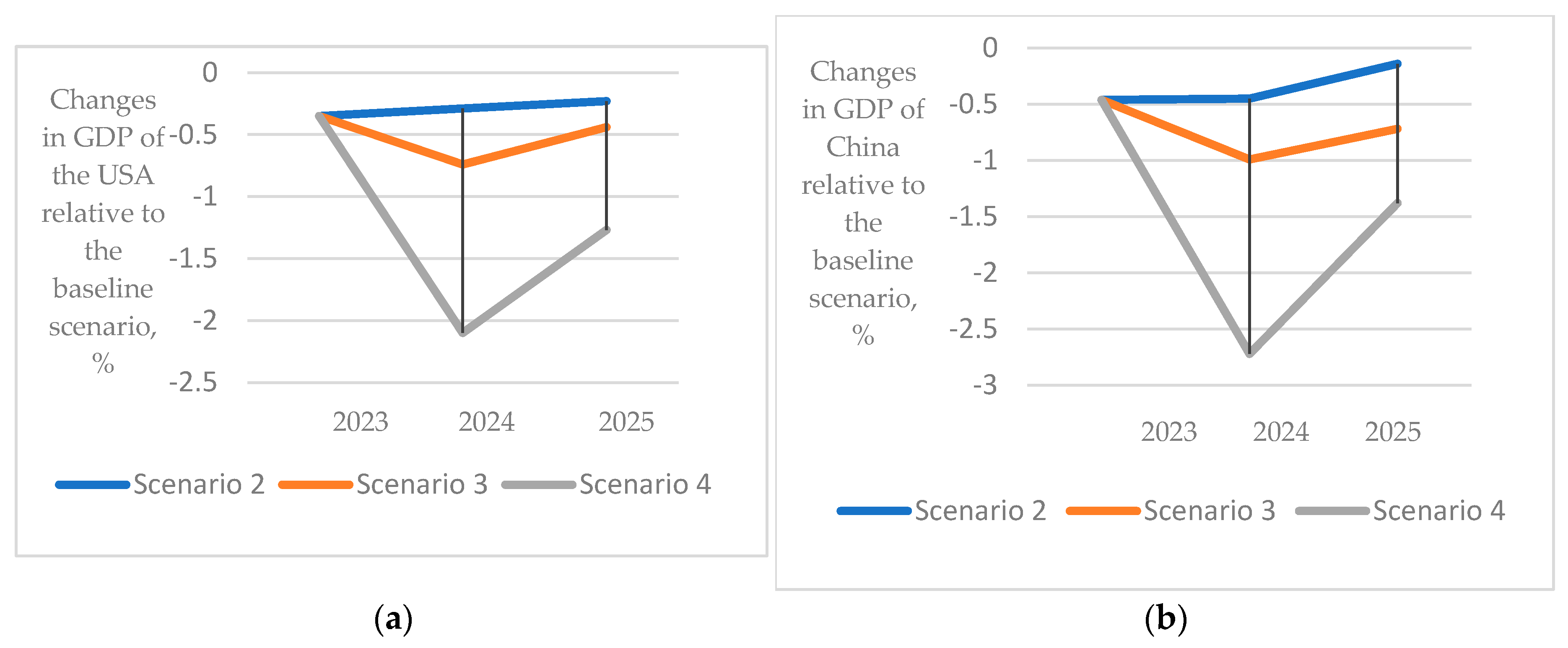

Calculations within Scenario 2 show a deviation of GDP within -0.5% for both the US and China, and the decline in China's GDP is more significant in the first two years after the introduction of a new package of sanctions, and in the third year the drawdown of this indicator is already smaller than for the USA (

Table 10).

The implementation of scenario No. 3 is expected in case of a local military conflict involving China in 2024, therefore, the scenario conditions assume the introduction of economic proxy war measures by the United States and the countries of the European Union both against China and against Russia, which is very likely to become its economical ally. Under these conditions, the economic slowdown of all countries participating in the conflict is prognosed to be within 1% of their GDP relative to the baseline scenario, with the most noticeable effect of mutual sanctions on the EU and China, which currently have close economic ties (

Table 11).

Scenario 4 considers the possibility of a global trade war, in which trade between Western countries and China decreases by 50% annually, with Russia by 25% annually (in addition to a 50% decrease in 2022). In this case, the world economy is experiencing a serious slowdown. The countries of the European Union are facing the most severe consequences, as for them decline of 2.4-3.3% means going into recession, while for the rest of the countries involved in the conflict, especially China, the forecasts indicate only a slowdown in growth rates to 1-2% per year (

Table 12).

Figure 3 compare the effects of different sanctions packages on the US and China. With some difference in values, there is a general trend in the decline in GDP relative to the baseline scenario with increased sanctions, and none of these countries can avoid serious consequences in case of a global trade war.

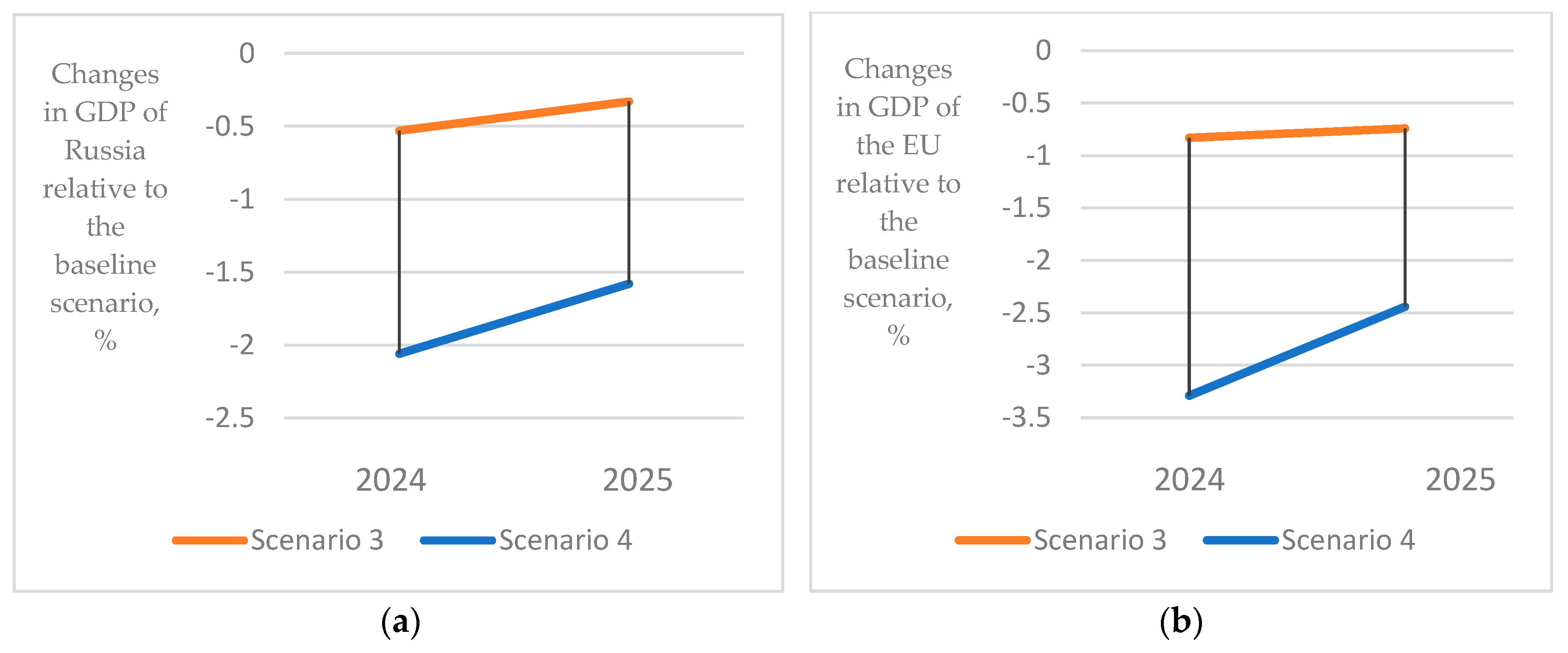

For Russia, the consequences of an aggravated trade war are expected to be less noticeable, since economic relations with Western countries have already been undermined after the events of 2022, and the weakening of China's trade with Western countries will lead to strengthening ties with it, beneficial to Russia. At the same time, the Russian economy is still expected to decline compared to the baseline scenario, which is associated with a general slowdown in the global economy, a drop in demand and prices for resources that Russia trades on international markets (

Figure 4a).

The effects of the global trade war are expected to be the most severe for the economies of the European Union, as China is their largest trading partner in imports (22.3% in 2021 according to Eurostat) and the second largest in exports (10.2%), which after the break of trade relations with Russia (7.7% of imports in 2021) inevitably leads to a recession, caused both by a lack of raw materials and components, and by shrinking markets for final products (

Figure 4b).

4. Conclusions

This paper presents the agent-based model of trade wars developed by the CEMI RAS team as part of a set of models of the socio-economic system of the Eurasian continent. This model expands the range of countries considered, including also the US and the rest of the world, which makes it possible to simulate global trade markets. The coverage of the entire world economy in the presented model puts it in a row with such projects as WorldScan, KPMG-MACRO and the global model for assessing consequences of a trade war between the United States and China. Unlike other similar projects, AOM of trade wars allows to assess consequences of introducing direct restrictions on the import and export of goods, which is increasingly being used as an instrument of sanctions pressure.

The paper also presents a comparison of forecasts obtained using various model complexes with the actually recorded consequences of economic conflicts. With regard to the trade confrontation between China and the United States, which began in 2018, the results of the global model developed by Chinese research teams for assessing consequences of trade wars proved to be the most accurate, while the forecasts of model complexes developed by Western teams turned out to be much further from reality. When assessing the impact of sanctions against Russia imposed in 2022, we used forecasts made in 2020 obtained on a set of models of the socio-economic system of the Eurasian continent, since, firstly, only in it Russia is considered as a key world economic player, and, secondly, it contains an instrument for imposing direct restrictions on the import and export of raw materials and goods. The forecasts of the World Bank and Bloomberg published in the spring of 2022 without specifying the tools used to build them were used as a basis for comparison. The forecast on the model of the Russian team turned out to be as close to reality as possible (a drop in GDP by 4% relative to the baseline scenario), while Western forecasts exaggerated this estimate by several times (a drop by 11-12%). This fact may be related to the sensitivity settings of the models and the sets of parameters used in them, but it does not exclude the possible fact that Western researchers are engaged to escalate tension in countries that have fallen under sanctions.

Thus, the developed model of trade wars showed high forecasting accuracy and was used for scenario calculations for the period up to 2025. In addition to the basic scenario for the development of world economies, scenarios of a slight increase in trade restrictions between China and the United States, the introduction of more serious sanctions against China and Russia by the US and the EU, and a global trade war were also considered. In the first scenario, the world economy as a whole maintains its trajectory, and the deviation of US and Chinese GDP from the baseline scenario does not exceed 0.5%. In the second case, the range of countries involved is expanding, and the fall in GDP in them is expected at the level of 0.7-1%. In the latter scenario, the entire world economy experiences a serious slowdown, and the countries of the European Union that are going into a recession face the most severe consequences.

An important direction in the development of the presented tool for predicting the consequences of trade wars is to include the rest of the BRICS countries (India, Brazil and South Africa) as separate participants, as well as take into account possible expansion of this association and its impact on world trade.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and A.B.; methodology, A.M. and A.B.; software, A.M. and A.B.; validation, A.M. and A.B.; resources, A.M. and A.B.; data curation, A.M. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and A.B.; supervision, A.M. and A.B.; project administration, A.M. and A.B.; funding acquisition, A.M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the RUSSIAN SCIENCE FOUNDATION within the framework of project No. 21-18-00136 "Development of a software and analytical complex for assessing the consequences of intercountry trade wars with an application for functioning in the system of distributed situational centers of Russia."

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mashkova, A.L.; Bakhtizin, A.R. Analyzing the industry structure and dynamics of commodity exchange between Russia, China, the USA and the EU under trade restrictions. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast 2023, 16, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, V.L.; Khabriev, B.R.; Bakhtizin, A.R.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z. Modern tools for evaluating the effects of global trade wars. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences 2019, 89, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corong, E.; Hertel, T.; McDougall, R. The Standard GTAP Model, Version 7. Journal of Global Economic Analysis 2017, 2, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, A.; Narayanan, B.; McDougall, R. An Overview of the GTAP 9 Data Base. Journal of Global Economic Analysis 2016, 1, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, J.; Rojas-Romagosa, H. Trade Wars: Economic impacts of US tariff increases and retaliations. An International Perspective. CPB Background Document 2018, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chunding, L.; Chuantian, H.; Chuangwei, L. Economic Impacts of the Possible China – US Trade War. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2018, 54, 1557–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Trade Wars: There are no winners. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2018/trade-wars-no-winners.pdf (accessed on 08 February 2019).

- Makarov, V.L.; Khabriev, B.R.; Bakhtizin, A.R.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z. World trade wars: scenario calculations of consequences. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences 2020, 90, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkova, A.L. Dynamics of investments in Russia under the conditions of sanction restrictions: Forecast based on an agent-based model. Business Informatics 2023, 17, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkova, A.; Bakhtizin, A. Assessment of Impact of Trade Wars on Production and Exports of the Russian Federation Using the Agent-Based Model. Advances in Systems Science and Applications 2022, 21, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal State Statistics Service. Available online: https://eng.rosstat.gov.ru/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China [Electronic source]. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. Available online: https://www.bea.gov/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- World bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/home (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- For Americans, Trump's tariffs on imports could be costly. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/politics/for-americans-trumps-tariffs-on-imports-could-be-costly (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Thomas Biesheuvel As China Fires Back in Trade War, Here Are the Winners And Losers. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-04/as-china-fires-back-in-trade-war-here-are-the-winners-and-losers (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- David, J. Lynch and Emily Rauhala With tariffs, Trump starts unraveling a quarter-century of U.S.-China economic ties. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-imposes-import-taxes-on-chinese-goods-and-warns-of-additional-tariffs/2018/06/15/da909ecc-7092-11e8-bf86-a2351b5ece99_story.html (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- David Lawder U.S. finalizes next China tariff list targeting $16 billion in imports. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-china/u-s-finalizes-next-china-tariff-list-targeting-16-billion-in-imports-idUSKBN1KS2CB (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Tae, K. China hits back: It will impose tariffs on $60 billion worth of US goods effective September 24. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/18/china-says-new-tariffs-on-us-goods-worth-60-billion-effective-sept-24.html (accessed on 31 July 2023).

Figure 1.

Countries considered in the agent-based model of trade wars.

Figure 1.

Countries considered in the agent-based model of trade wars.

Figure 2.

Program structure of the agent-based model of trade wars.

Figure 2.

Program structure of the agent-based model of trade wars.

Figure 3.

Expected dynamics of GDP of the involved countries in case of introduction of various packages of sanctions: (a) the USA; (b) China.

Figure 3.

Expected dynamics of GDP of the involved countries in case of introduction of various packages of sanctions: (a) the USA; (b) China.

Figure 4.

Expected dynamics of GDP in case of growing global trade confrontation: (a) Russia; (b) the EU.

Figure 4.

Expected dynamics of GDP in case of growing global trade confrontation: (a) Russia; (b) the EU.

Table 1.

Forecast of changes in GDP of the USA and China in the context of a mutual increase in import duties according to the results of calculations on various model complexes.

Table 1.

Forecast of changes in GDP of the USA and China in the context of a mutual increase in import duties according to the results of calculations on various model complexes.

| Model complex |

Increase in import duties, % |

Changes in GDP of the USA relative to the baseline scenario, % |

Changes in GDP of China relative to the baseline scenario, % |

| WorldScan |

2.5 |

-1.4 |

-2.1 |

| 5 |

-2.3 |

-3.1 |

| 10 |

-2.9 |

-3.8 |

| 15 |

-3.1 |

-4 |

| Global model for assessing consequences of a trade war between the USA and China |

15 |

0.007 |

-0.667 |

| 60 |

0.126 |

-1.790 |

| KPMG-MACRO |

15 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

| 25 |

-0.7 |

-1.0 |

| 15 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

| 25 |

-0.7 |

-1.0 |

Table 2.

GDP dynamics of the USA and China in 2013-2022, as a percentage of the previous year.

Table 2.

GDP dynamics of the USA and China in 2013-2022, as a percentage of the previous year.

| Country |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| The USA |

1,8 |

2,3 |

2,7 |

1,7 |

2,2 |

2,9 |

2,3 |

-2,8 |

5,9 |

2,1 |

| China |

7,8 |

7,4 |

7,0 |

6,8 |

6,9 |

6,7 |

6,0 |

2,2 |

8,1 |

3,0 |

Table 3.

Average annual GDP dynamics of the USA and China in the two-year and five-year period.

Table 3.

Average annual GDP dynamics of the USA and China in the two-year and five-year period.

| Country |

Average 5-year dynamics |

Average 2-year dynamics |

| 2013-2017 |

2018-2022 |

2016-2017 |

2018-2019 |

| The USA |

2,1 |

2,1 |

2,0 |

2,6 |

| China |

7,2 |

5,2 |

6,9 |

6,4 |

Table 4.

Forecasts of changes in Russia's GDP in the first year after the introduction of international sanctions.

Table 4.

Forecasts of changes in Russia's GDP in the first year after the introduction of international sanctions.

| CMSESEC prognosis, as a percentage relative to the baseline scenario, while restricting exports from Russia to the USA and the EU for: |

World Bank forecast, as a percentage of the previous year |

Bloomberg forecast, as a percentage of the previous year |

| 10% |

20% |

30% |

| -1.43 |

-2.74 |

-3.88 |

-11.2 |

-12 |

Table 5.

Dynamics of Russian GDP in 2013-2022, as a percentage of the previous year.

Table 5.

Dynamics of Russian GDP in 2013-2022, as a percentage of the previous year.

| Year |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| GDP dynamics, % |

4 |

1,8 |

0,7 |

-2 |

0,2 |

1,8 |

2,8 |

2,2 |

-2,7 |

5,6 |

-2,1 |

Table 6.

Dynamics of trade turnover between the USA and China in 2017-2022.

Table 6.

Dynamics of trade turnover between the USA and China in 2017-2022.

| Type of a trade flow |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| The USA imports (overall), million USD |

2904820 |

3121057 |

3105952 |

2812640 |

3401685 |

3957174 |

| The USA imports from China, million USD |

524042 |

558324 |

469541 |

448879 |

526807 |

563923 |

| Share of China in the USA imports, % |

18 |

17,9 |

15,1 |

16 |

15,5 |

14,3 |

| The USA exports (overall), million USD |

2394476 |

2542462 |

2546276 |

2158651 |

2556638 |

3011855 |

| The USA exports to China, million USD |

187875 |

180596 |

167475 |

166274 |

192038 |

197841 |

| Share of China in the USA exports, % |

7,8 |

7,1 |

6,6 |

7,7 |

7,5 |

6,6 |

Table 7.

Dynamics of trade turnover between China and the USA in 2017-2022.

Table 7.

Dynamics of trade turnover between China and the USA in 2017-2022.

| Type of a trade flow |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| China's imports (overall), million USD |

1410000 |

1600000 |

1570000 |

1550000 |

1970000 |

1942420 |

| China's imports from the USA, million USD |

187875 |

180596 |

167475 |

166274 |

192038 |

197841 |

| Share of the USA in China's imports, % |

13,3 |

11,3 |

10,7 |

10,7 |

9,7 |

10,2 |

| China's exports (overall), million USD |

2420000 |

2630000 |

2610000 |

2650000 |

3340000 |

3590000 |

| China's exports from the USA, million USD |

524042 |

558324 |

469541 |

448879 |

526807 |

563923 |

| Share of the USA in China's exports, % |

21,7 |

21,2 |

18 |

16,9 |

15,8 |

15,7 |

Table 8.

Dynamics of the share of China in US imports by main commodity groups in 2017-2022, in percent.

Table 8.

Dynamics of the share of China in US imports by main commodity groups in 2017-2022, in percent.

| Commodity group |

China's share in imports, % |

| 2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages |

4,4 |

4,5 |

3 |

2,9 |

2,6 |

2,6 |

| Industrial supplies and materials |

9,4 |

9,6 |

8 |

8,8 |

7,2 |

7,2 |

| Capital goods except automotive |

29,6 |

28,8 |

22,7 |

23,2 |

22,7 |

20,3 |

| Automotive vehicles, parts, and engines |

5,6 |

6,2 |

4,5 |

4,6 |

5,3 |

5,4 |

| Consumer goods except food and automotive |

39 |

38,2 |

34,2 |

34 |

33,1 |

31,6 |

Table 9.

Dynamics of China's share in US exports by main commodity groups in 2017-2022, in percent.

Table 9.

Dynamics of China's share in US exports by main commodity groups in 2017-2022, in percent.

| Commodity group |

China's share in exports, % |

| 2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages |

13,8 |

6,1 |

10,1 |

17,6 |

18,6 |

19,5 |

| Industrial supplies and materials |

9,4 |

7,7 |

5,6 |

8,6 |

8,1 |

6,3 |

| Capital goods except automotive |

8,9 |

9,4 |

8,2 |

9,2 |

9,5 |

7,9 |

| Automotive vehicles, parts, and engines |

8,8 |

6,6 |

6,1 |

7,2 |

6,6 |

5,2 |

| Consumer goods except food and automotive |

3,6 |

3,7 |

4,5 |

5,3 |

5,4 |

6 |

Table 10.

Results of calculations for scenario No. 2 for the USA and China.

Table 10.

Results of calculations for scenario No. 2 for the USA and China.

| Year |

Changes in GDP of the USA relative to the baseline scenario, % |

Changes in GDP of China relative to the baseline scenario, % |

| 2023 |

-0,35 |

-0,46 |

| 2024 |

-0,29 |

-0,45 |

| 2025 |

-0,23 |

-0,14 |

Table 11.

Results of calculations under scenario No. 3 for China, the USA, Russia and the EU.

Table 11.

Results of calculations under scenario No. 3 for China, the USA, Russia and the EU.

| Year |

Changes in GDP of countries involved in the trade conflict relative to the baseline scenario, % |

| Russia |

The EU |

The USA |

China |

| 2024 |

-0,53 |

-0,83 |

-0,74 |

-0,99 |

| 2025 |

-0,33 |

-0,74 |

-0,44 |

-0,72 |

Table 12.

Results of calculations for scenario No. 4 for the countries involved and the rest of the world.

Table 12.

Results of calculations for scenario No. 4 for the countries involved and the rest of the world.

| Year |

Changes in GDP of countries involved in the trade conflict relative to the baseline scenario, % |

Changes in GDP of the rest world relative to the baseline scenario, % |

| Russia |

The EU |

The USA |

China |

| 2024 |

-2,06 |

-3,29 |

-2,1 |

-2,72 |

-1,12 |

| 2025 |

-1,58 |

-2,44 |

-1,27 |

-1,38 |

-1,25 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).