1. Introduction

Workplace incivility is defined as “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect. Uncivil behaviors are characteristically rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others” (Andersson & Pearson, 1999, p.457). This can be instigated from multiple sources at workplace, including supervisors, colleagues, customers, etc. Even students can be the instigators of incivility in educational institutions. Discourteous and insulting behavior can be highly damaging for mental and physical health of incivility targets (Lim et al., 2008). The contagious nature of incivility is too dangerous and its effect spread sharply through spillover and crossover mechanism. This issue can thus disrupt the behaviors of many individuals and functioning at many places, in parallel. Incivility, therefore, holds significant costs for individuals, institutions, and societies (Porath et al., 2015; Fritz et al., 2019). Such issues at workplace can create serious negative repercussions for performance and supportive attitude of employees (De Clercq et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019). The more damaging aspect of workplace incivility is the higher negative consequences for committed employees.

The behavioral problems prevails in almost every organizational type, even in educational institutions. Indeed, this is more bitter and problematic in educational sector. A positive and civilized conduct in educational institutes could make the teachers and students satisfied and better-off (Apaydin & Seckin, 2013). It can promote a friendly teaching-learning environment and everyone feel pleasure to contribute voluntarily in the activities related to individual and organizational development. Sense of mutual respect could be helpful in promoting the organizational citizenship behavior of all concerned (Cavus, 2012). In contrast, the uncivil acts can damage the organizational culture badly. It may create stress, frustration, and displeasure among the members. The individuals, in such an environment, find it difficult to perform their activities effectively. It can thus severely damage the productivity and efficiency of individuals and organizations. In educational institutions, the incivility concerns can create displeasure and strain among the teachers. The discourteous actions of teachers, students, or any other stakeholder can damage the learning abilities and classroom environment, while negatively affecting the interpersonal relationships (Yassour-Borochowitz & Desivillia, 2016; Ibrahim & Qalawa, 2016).

The behavior and dealing of colleagues can play an important role in the organizations. The moral support of colleagues could enable to absorb any sort of anticipated or unanticipated shock much effectively. Such an attitude could be helpful to overcome the issues of depression, stress, and anxiety, thereby increasing the productivity and performance of individuals. The discourteous attitude of colleagues, on the other side, can produce negative emotions, reduce work efforts, and enhance counterproductive work behavior (Sakurai & Jex, 2012). Another harmful aspect of such uncivil concerns is its transmission to the family domain, thereby creating work-family conflict (Chen, 2018). These incivility incidents not only affect the performance directly, but can also indirectly affect via emotional exhaustion (Hur et al., 2015; Rhee et al., 2016). Impolite dealings could create emotional tiredness among the victims (Totterdell et al., 2012) which then lower performance and increase turnover intentions (Cho et al., 2016). In this entire situation, one positive aspect can be the resilient personality traits of individuals, facing such issues. Such individuals can absorb the unpleasant shocks more effectively and be able to confine the negative outcomes. Personality hardiness can reduce the impact of stress, stimulates courage to work hard, transform probable tragedies into growth, and enhance the level of organizational commitment (Westman, 1990; Maddi, 2006; Sezgin, 2009).

This study is expected to contribute in atleast three ways. First, the study is uncovering to a chronic issue in the region that needs to be addressed properly for betterment of individuals, organizations, and the State. Secondly, the study is incorporating the role of emotions and hardiness in parallel by addressing their contributions to propagate or neutralize the shocks. Thirdly, the study is addressing to extra-role component of performance, which is more relevant to voluntary contributions and organizational citizenship behavior. The development of such behavior and culture could definitely be helpful at individual and organizational level. The findings are expected to be helpful in developing an understanding of the repercussions associated with discourteous behaviors and mistreatments at workplace, and devising appropriate mechanism to reduce its occurrence and to confine its impact.

1.1. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

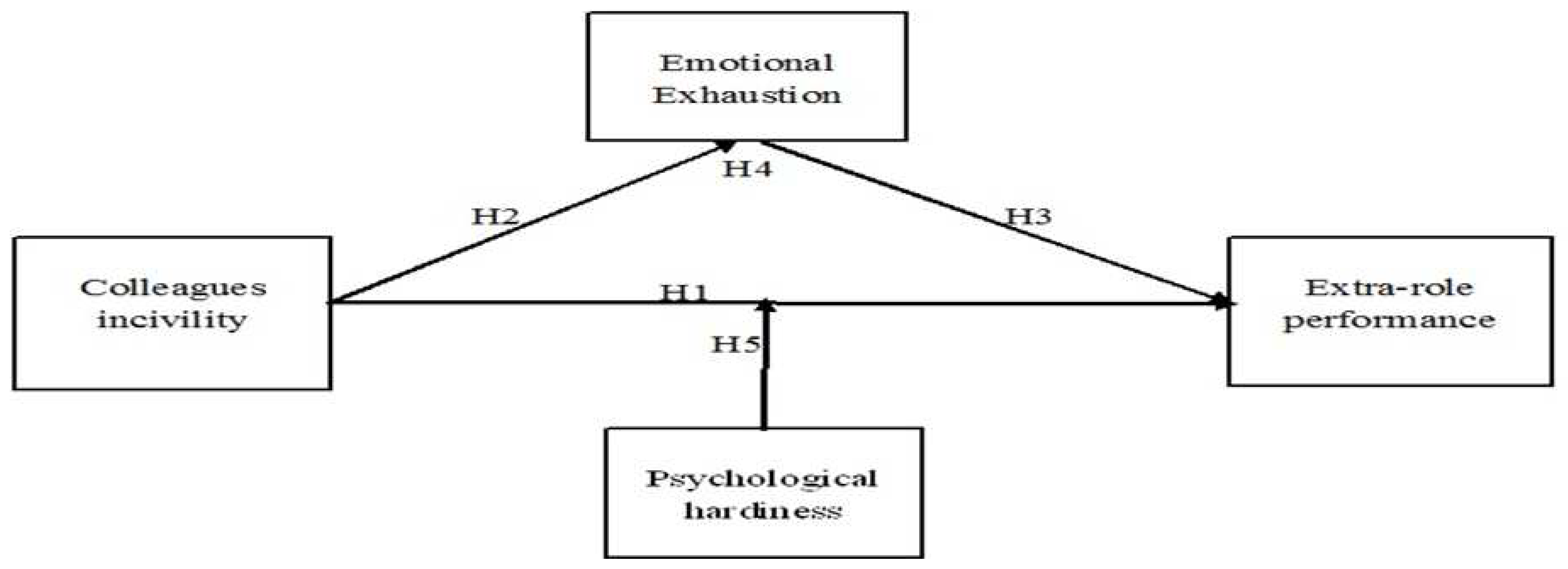

Theoretical foundation of this study is principally based on affective events theory (AET) of Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), conservation of resources model (COR) originated by Hobfoll (1989), and psychological hardiness model of Kobasa (1979). Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) promulgated the affective events theory (AET) to explain the causes of affective experiences at workplace and its associated impact on performance and job satisfaction of individuals. Different positive and negative events may occur at workplace, having different implications. The negative events generally hold more implications for emotional and psychological reaction patterns (Taylor, 1991). However, this reaction pattern may largely differ for individuals, based on their personality characteristics. Based on these basic notions, the conceptual model of the study is designed and presented in

Figure 1. Detailed mechanism of hypotheses development is in subsequent sections.

1.2. Colleagues incivility and job outcomes

Workplace incivility is a chronic issue that has severely damaged the productivity and performance of different individuals and organizations. Evidences indicate that the behavioral issues at workplace put severe repercussions for its initiators, witnesses, and victims (Schilpzand et al., 2016). Such issues can thus disrupt the entire organizational culture and system. Interpersonal mistreatment at workplace also create and intensify the psychological distress among the individuals, facing such issues (Cortina et al., 2001; Adams & Webster, 2013; Abubakar, 2018). Moreover, it places negative effect on health of employees and enhances their turnover intentions (Lim et al., 2008). Uncivil behaviours at workplace not only affect the job satisfaction but also create depression and stress, thereby disrupting the life satisfaction (Miner et al., 2012). Incivility is, therefore, so chronic that it can negatively affect many persons and places simultaneously. Many researchers reported the damaging personal and performance consequences of colleagues’ discourteous actions at workplace (Schilpzand et al., 2016; Rhee et al., 2016). Earlier studies also reported that impoliteness of colleagues at workplace instigates emotional tiredness among the victims, which then reduces the performance of individuals and efficiency of organizations (Hur et al., 2015; Cho et al., 2016; Viotti et al., 2018). This study also intended to extend such claims, for which it is hypothesized that:

H1: Extra-role performance of teachers at job is negatively affected by the incivility of colleagues.

H2: Emotional exhaustion of teachers is positively influenced by incivility of their colleagues.

1.3. Role of emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion signifies the state of mind in which the individuals feel emotionally drained, on account of accumulated stress from work or family life, or of both. Exhausted employees find it difficult to discharge the responsibilities with concentration and commitment. This mind set is extremely dangerous for individuals and organizations. Considering the sternness of issue, many researchers across the world empirically explored this phenomenon and reported serious negative consequences. Most of the studies observed a negative association of emotional exhaustion with job performance, satisfaction, and commitment of exhausted employees (Wright & Cropanzano, 1998; Moon & Hur, 2011). This situation also significantly influences the turnover intentions and productive activities of the employees. Exhausted attitude not only influences the performance directly, but can also mediate to intensify the effect of workplace incivility on individuals and organizational outcomes (Sakurai & Jex, 2012; Hur et al., 2015; Rhee et al., 2016; Huang & Lin, 2019). Findings of existing studies indicated that the discourteous attitude of colleagues at workplace can create emotional exhaustion, which then negatively affect the job performance and satisfaction, reduce work efforts, enhance turnover plans, and produce counterproductive work behaviors. To examine the direct and mediating mechanism of emotional exhaustion, we hypothesize:

H3: Extra-role performance of teachers at job is negatively affected by their emotional exhaustion.

H4: The negative effect of colleagues’ incivility on teachers’ extra-role performance is fully mediated by their emotional exhaustion.

1.4. Psychological hardiness as moderator

Hardiness reflects to the set of personality characteristics, providing a defensive shield to the individuals against stressful and unpleasant life events. Such individuals can effectively counter the pressures and problems, inside and outside the workplace. This concept was first introduced by Kobasa (1979), after which numerous contributions were made from different aspects. Researchers highlighted the significance of hardiness for stress management, organizational commitment, and effective performance of employees (Bartone et al., 2008; Sezgin, 2009). Hardiness can provide a courage and motivation for working hard, enabling to convert possible disasters to growth opportunities (Maddi, 2006). Hardiness was also noticed to be associated negatively with stress while positively with job related outcomes. Many past studies observed a buffering role of hardiness to reduce the impact of workplace incivility and stress on health and job related outcomes of hardy individuals (Westman, 1990; Blgbee, 1992; Hystad et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2018). In line with previous research, the current research also intended to examine the moderating mechanism of psychological hardiness in the effect of colleagues’ incivility on job performance of teachers, for which it is hypothesized:

H5: The negative effect of colleagues’ incivility on teachers’ extra-role performance is moderated by their psychological hardiness, such that the effect is weaker for hardy teachers

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and sample

This study targeted the teachers of public sector universities in AJ&K. Incivility in educational institutions is a chronic issue, having sever repercussions for all stakeholders and for overall learning environment (Zabrodska & Kveton, 2013; Itzkovich & Dolev, 2017). The reason of concentrating public sector only is the exposure of teachers to nearly similar rules and regulations (Soomro et al., 2018). For empirical analysis, the study selected a sample of regular teachers and their HoDs from recognized universities of the State. Contract, adhoc, and tenured teachers were not included in the sample. The teachers with some sort of administrative responsibilities were also excluded to avoid biasness and ensure fair representation. Similarly, certain criteria regarding minimum experience and maximum respondents from a single department was also specified. The pre-defined criteria has induced the researchers to apply the purposive sampling technique. Final sample of the study was comprised of 403 teachers (male = 235, female = 168). Following Mckay et al. (2008), Dettmers (2017), the codes were specified for universities and teachers to avoid identification and biasness, while ensuring confidentiality and sample matching required for dyadic approach. The participation in the research process was voluntary and respondents were free to withdraw from the data collection process at any stage. The respondents were taken into confidence that the data would be used only for academic purposes and no details would be shared with corresponding dyads.

2.2. Measures

Following, Abdollahi et al. (2018), each questionnaire set was reviewed by two faculty members from each public sector university of AJ&K to judge the content and face validity of scale as well as its feasibility in each local cultural setting. The study applied 5-point Likert scale with anchors (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3= neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree) for seeking responses pertaining to all the variables, excluding colleagues incivility. For colleagues incivility, a 5-point Likert scale with anchors (1 = never, 2 = once or twice. 3 =sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = many times) was applied. For determining the reliability of measures, a matched dyadic sample of 75 teachers and respective heads was selected for pilot testing. On the basis of collected responses, reliability of measures was examined by applying Cronbach’s Alpha. Alpha value of each scale was above 0.70, which endorsed the reliability of instrument.

2.2.1. Colleagues incivility

For determining the colleagues’ incivility, the study applied workplace incivility scale of Martin and Hine (2005), which was comprised of 17 items. The sample items of this scale were, “Used an inappropriate tone when speaking to you”, “Made snide remarks about you” (Cronbach’s α = .78).

2.2.2. Emotional exhaustion

To determine the emotional exhaustion of teachers, the study applied 8-items OLBI instrument by following Demerouti et al. (2003), Demerouti et al. (2010). The beauty of this instrument is the same number of direct and reverse coded items. The sample items include, “During my work, I often feel emotionally drained”, “When I work, I usually feel energized” (Cronbach’s α = .91).

2.2.3. Psychological hardiness

The moderating role of psychological hardiness was examined with the help of 15-items scale from the study of Hystad et al. (2010), and based on measures of Bartone et al. (1989). This scale is composed of three major personality characters, i.e. commitment, control, and challenge. The sample items of this scale include, “I really look forward to my work activities”, “It is up to me to decide how the rest of my life will be”, and “I like having a daily schedule that doesn’t change very much” (Cronbach’s α = .87).

2.2.4. Extra-role performance

Responses regarding teachers’ extra-role performance in departments and organizations were sought by using 14-items scale of Williams and Anderson (1991). The sample items of this scale were, “He/she takes undeserved work breaks”, “He/she conserves and protects organizational property” (Cronbach’s α = .91).

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The data were collected in three different phases. Following Liang (2015), Alola et al. (2019), questionnaires were mailed to individual respondents separately in sealed envelopes. Moreover, dyadic and time lagged data collection approaches were used, where respondent teachers and their supervisors were approached in separate time intervals. Many past studies, including of Karatepe (2013), De Clercq et al. (2018), Fatima et al. (2020) were followed in this context. Time lagged data collection method helped to overcome the issues of common method biases. Responses regarding colleagues’ discourteous treatment were collected in the first round. After the completion of this round and maintaining appropriate time interval, the second round was initiated to collect the responses on emotional exhaustion and psychological hardiness. In the final round, the feedback regarding teachers’ performance was sought from their HoDs. The systematic follow up helped to attain an appropriate response rate.

The collected data was then analyzed for meaningful inferences, with the help of statistical tools and software. Initially, the basic features and suitability of data were examined with the help of descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Based on the concept of Campbell and Fiske (1959), the study then established the validity and reliability of responses. In the next step, structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS was carried out to examine the hypothesized direct effects. This approach remained popular among researchers in the field of social sciences and had been applied in many past studies, e.g. Lim et al. (2008), Dettmers (2017), Huang and Lin (2019), Anasori et al. (2020). Feasible measurement models were identified with the help of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). For establishing models fitness, commonly used fit indices were applied, i.e. CMIN/DF, RMSEA, IFI, TLI, AGFI, CFI. Following the recent studies of De Clercq et al. (2019), Alola et al. (2019); PROCESS macro of Hayes (2013) were applied for testing mediation and moderation. Mediation split technique was also applied for further confirmation and robustness of results.

3. Results

The basic features of collected data were determined by using SPSS 24.

Table 1 reports the results of descriptive statics, correlation, reliability, and validity analysis.

Regarding descriptive statistics, the higher mean value depicts the inclinations of respondents towards agreement side. The output values of colleagues incivility (mean= 2.30, S.D = 0.74) and emotional exhaustion (mean= 2.76, S.D = 0.84) indicates a nearly balanced position. However, the values of psychological hardiness (mean= 3.69, S.D = 0.83) and extra-role performance (mean= 3.56, S.D = 0.81) tilts more to agreement side. Each scale carried certain number of reverse coded items. Incivility of colleagues was found to be correlated positively and significantly with emotional exhaustion (r = 0.381, p < .001) while negatively and significantly with hardiness (r = -0.106, p < .100) and extra-role performance (r = -0.205, p < .001). Significant negative correlation of emotional exhaustion was found with extra-role performance (r = -0.438, p < .001), but it remained insignificant for psychological hardiness (r = -0.032). The study also observed the hardiness be positively and significantly correlated with extra-role performance (r = 0.293, p < .001).

Table 1 further portrays a greater than 0.70 and 0.50 values of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE), respectively. Moreover, AVE values remained higher than the corresponding MSV values, in each case. These computed values were above the threshold levels, specified by Hair et al. (2014), Henseler et al. (2015). Hence, validity and reliability of measures were established. After examining the basic data characteristics, fit indices were determined and reported in

Table 2.

The default measurement model shown poor values of some indices (RMSEA= 0.07, TLI = 0.89 and AGFI = 0.82). To secure more desirable fit indices, modification analysis was conducted, which then produced better results (χ2/df = 2.11, RMSEA= 0.05, IFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.91, and CFI = 0. 96). Following appropriate model selection, the study examined the hypothesized direct effects, and its results are reported in

Table 3.

Empirical results, reported in

Table 3, supported the first three hypothesized effects. The effect of colleagues’ incivility remained negative and significant for extra-role performance (β = -.210, p < .001), while positive and significant for emotional exhaustion (β = .380, p < .001). Similarly, the effect of exhaustion on performance was found negative and significant (β = -.435, p < .001). The study then proceeded further to examine the mediating role of emotional exhaustion, with the help of model proposed by Hayes (2013) and results are reported in

Table 4.

The results in

Table 4 depict for significant mediation of emotional exhaustion in the effect of colleagues’ incivility on extra-role performance of teachers at job (β = -0.162, p< .001, CI = -0.223~-0.105). The absence of ‘0’ value between lower and upper limit at 95% confidence interval supported for mediation of emotional exhaustion, as proposed in H4. The study further applied the similar model of Hayes (2013) to examine the moderating role of psychological hardiness in the hypothesized effect. The results of moderation are presented in

Table 5.

Results indicated a significant negative effect of colleagues incivility on extra-role performance of teachers (β=-0.205, p<.001) but with psychological hardiness, the effect became weaker and turned positive (β=0.147, p<.01). Hardiness thus remained helpful to absorb the unpleasant shock effectively, thereby putting minimum impact on job outcomes. For further confirmation and robustness of moderation results, mediation split technique was applied and its results are reported in

Table 6.

Psychological hardiness (PH) was tested as a moderator between colleagues’ incivility (CI) and extra-role performance (ERP) of teachers. PH was dichotomized through the median split method. Results shown in Table 7 demonstrate an insignificant moderating effect of low psychological hardiness but higher hardiness was observed to be significantly moderating the relationship between colleague’s incivility and extra-role performance of teachers at job. These findings suggests that there was no major change in the negative effect of CI on ERP in the presence of low PH. On the other hand, higher PH has enhanced ERP by lessening the negative effect of CI.

4. Limitations and future research opportunities

The research is not free of limitations and should be considered while interpreting the results. First limitation is relevant to generalizability of findings. Sample of the study was selected from a specific region of the country on the basis of purposive sampling. Purpose sampling was used to address the research questions by collecting data from a sample possessing the specified qualities. However, one particular limitation of purposive sampling includes nonrandom selection of the participants which can be a potential researchers’ bias and may affect the generalizability of findings. Researchers may address this aspect by taking a broader sample from all regions of the country. The cross-country and cross-cultural studies can even be more fruitful to uncover the phenomenon more systematically. Second limitation is relevant to the incorporation of only one segment of incivility at workplace, i.e. colleagues. At workplace, there can be multiple instigators of incivility concerns, which can even be more problematic as compared to colleagues. Efforts may be placed in future studies to identify the other major instigators of uncivil actions and the associated outcomes. Third limitation of the study is relevant to the applications of supervisors-rated measures only for examining the performance of teachers. This can be extended in future by incorporating the students-rated, peer-rated, or society-rated measures. Fourth limitation is related to the mediating and moderating mechanism, as the study only examined one mediator and one moderator. There can be multiple factors that may either mediate or buffer the effect. Future studies may be proceeded to uncover the mediation and moderation of certain other factors in hypothesized effects, such as the mediation of psychological detachment, stress, and job dissatisfaction. Similarly, the moderation of psychological, social, and moral support may be explored in future studies

5. Discussion

Based on findings, the study offered different policy implications. The study covered three dimensions in parallel, i.e. direct effect of colleagues’ incivility on performance of respondents, mediating role of emotional exhaustion, and the moderating role of psychological hardiness. In this way, the study endorsed, extended, and contributed in the affective events theory of Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), conservation of resources model of Hobfoll (1989), and hardiness model of Kobasa (1979). The study also fills the gap in existing literature by addressing the issue in a region having unique cultural norms and values. Examining the phenomenon in this part of the world is relatively distinctive and could hold valuable contextual implications. The study further offered policy implications and recommendations for administration of the universities. Keeping in mind the harmful effects of incivility concern, it is suggested to set a proper accountability mechanism for instigators of uncivil acts and behaviors. The universities should especially adopt zero tolerance policy in this context, as earlier suggested by Blanco-Donoso et al. (2019). Such policies should be well formulated, approved from regulatory bodies, and disseminated at all level. This would be helpful to develop an understanding of workplace norms and to create an environment of mutual respect and cooperation in the institutions. Regular training programs and awareness seminars could also be helpful to confine incivility incidents and associated outcomes (Milam et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2019). The universities should arrange such activities at a broader level with the intention of creating a civility culture at organizational, societal, and national level.

Based on mediation analysis, the study also suggested for providing trainings on emotional intelligence to the employees. Similar suggestions were earlier made by Bibi et al. (2013), Raman et al. (2016). Emotional speakers may be invited in such trainings and workshops. Emotional stability could reduce the probability of exhaustion and emotional disorder in the situation of unpleasant events and interactions. In this way, negative repercussions for individuals and organizations could be curtailed. The study further endorsed the suggestions of Andersson and Pearson (1999), De Clercq et al. (2018) to consider the personality constructs of individuals in hiring process. As observed in the study, the psychological hardiness effectively buffered the effects of colleagues’ discourteous behaviour. Courteous, polite and supportive employees could not only manage the unpleasant shocks by themselves but also help others to absorb such shocks, and thus can develop an overall conducive working environment in the organizations. Further, the findings have pedagogical implications and an important aspect of the study is its respondents who were teachers and departmental chairs of higher education institutions. Implications include the importance for faculty members to develop a voluntary code of conduct for promoting friendly, cooperative, and exemplary environment at workplace, free from any sort of uncivil action and base on the sense of mutual respect and harmony. The teachers may also share with their students the harmful consequences of incivility for individuals, organizational, and societal development. Moreover, the curriculum may be refined to develop the interpersonal, emotional, psychological, and social skills and abilities of the students so that they may be able to effectively cope the stressful events and can become effective, responsible, and valuable national asset.

6. Conclusions

As hypothesized, the study found a significant negative effect of colleagues’ incivility on performance of respondents. In addition, incivility positively affected the emotional exhaustion, which again negatively affected the performance of teachers at job. This shows that incivility is very dangerous, carrying substantial costs for individuals and organizations. The study findings further clarified that incivility not only directly affects the behavior of targets, but also indirectly effect via emotional exhaustion. Efforts should, therefore, be made to overcome this chronic issue in the organizations. The study, however, observed and reported a positive sign regarding the buffering mechanism of psychological hardiness to absorbing the effects of unpleasant events. It was concluded that incivility is a chronic issue, but certain remedial measures could make it possible to overcome this issue and its associated negative outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H.S., K.A., M.A.S. and N.S.; methodology, N.H.S., M.K., and K.A.; software, S.A., N.H.S., M.A.S. and N.S.; validation, M.A.S., N.H.S., K.A. and S.A.; formal analysis, N.H.S., N.S., S.A. and M.A.S.; investigation, M.S., S.A. I.R., K.A. and N.H.S.; resources, M.S; data curation, S.A and M.S..; writing—original draft preparation, K.A., N.H.S., M.A.S., M.K. and N.S.; writing—review and editing, M.K., M.A.S. I.R. and S.A.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, N.H.S.; project administration, N.H.S., M.A.S. and K.A.; funding acquisition, K.A., I.R. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol for this study received approval from the Ethical Committee of University of Kotli, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan (Approval No. EC/UOKAJK/2022/004).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to pay thanks to all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdollahi, A.; Abu Talib, M.; Carlbring, P.; Harvey, R.; Yaacob, S.N.; Ismail, Z. Problem-solving skills and perceived stress among undergraduate students: The moderating role of hardiness. Journal of Health Psychology 2018, 23, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.A. Linking work-family interference, workplace incivility, gender and psychological distress. Journal of Management Development 2018, 37, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.A.; Webster, J.R. Emotional regulation as a mediator between interpersonal mistreatment and distress. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2013, 22, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, U.V.; Olugbade, O.A.; Avci, T.; Ozturen, A. Customer incivility and employees' outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tourism Management Perspectives 2019, 29, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, E.; Bayighomog, S.W.; Tanova, C. Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. The Service Industries Journal 2020, 40, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. The Academy of Management Review 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, C.; Seckin, M. Civilized and uncivilized behaviors in the classroom: An example from the teachers and students from the second stage of primary education. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 2013, 13, 2393–2398. [Google Scholar]

- Bartone, P.T.; Roland, R.R.; Picano, J.J.; Williams, T.J. Psychological hardiness predicts success in US army special forces candidates. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 2008, 16, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T.; Ursano, R.J.; Wright, K.M.; Ingraham, L.H. The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers: A prospective study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1989, 177, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibi, Z.; Karim, J.; ud Din, S. Workplace incivility and counterproductive work behavior: Moderating role of emotional intelligence. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research 2013, 28, 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Amutio, A.; Moreno-Jimenez, B.; Yeo-Ayala, M.C.; Hermosilla, D.; Garrosa, E. Incivility at work, upset at home? Testing the cross-level moderation effect of emotional dysregulation among female nurses from primary health care. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2019, 60, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blgbee, J.L. Family stress, hardiness, and illness: A pilot study. Family Relations 1992, 41, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavus, M.F. Socialization and organizational citizenship behavior among Turkish primary and secondary school teachers. Socialization and Organizational Citizenship Behavior 2012, 43, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-C. The relationships between multifoci workplace aggression and work-family conflict. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2018, 29, 1537–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.H. Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2016, 28, 2888–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U.; Ahmad, H.N. The relationship between workplace incivility and helping behavior: Roles of job dissatisfaction and political skill. The Journal of Psychology 2019, 153, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U.; Raja, U. Family incivility, emotional exhaustion at work, and being a good soldier: The buffering roles of way power and willpower. Journal of Business Research 2018, 89, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Vardakou, I.; Kantas, A. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2 0036, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Mostert, K.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2010, 15, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmers, J. How extended work availability affects well-being: The mediating roles of psychological detachment and work-family-conflict. Work & Stress 2017, 31, 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, T.; Majeed, M.; Jahanzeb, S. Supervisor undermining and submissive behavior: Shame resilience theory perspective. European Management Journal 2020, 38, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M. You cannot leave it at the Office: Spillover and crossover of co-worker incivility. Journal of Organizational Behaviour 2012, 33, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Park, Y.; Shepherd, B.R. Workplace incivility ruins my sleep and yours: The costs of being in a work-linked relationship. Occupational Health Science 2019, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, 1st ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-T.; Lin, C.-P. Assessing ethical efficacy, workplace incivility, and turnover intention: A moderated-mediation model. Review of Managerial Science 2019, 13, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, B.-S.; Park, S.-J. The relationship between coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries 2015, 25, 701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Hystad, S.W.; Eid, J.; Johnsen, B.H.; Laberg, J.C.; Bartone, P.T. Psychometric properties of the revised Norwegian dispositional resilience (hardiness) scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2010, 51, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, S.W.; Eid, J.; Laberg, J.C.; Johnsen, B.H.; Bartone, P.T. Academic stress and health: Exploring the moderating role of personality hardiness. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 2009, 53, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.E.-A.; Qalawa, S.A. Factors affecting nursing students' incivility, as perceived by students and faculty staff. Nurse Education Today 2016, 36, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkovich, Y.; Dolev, N. The relationships between emotional intelligence and perceptions of faculty incivility in higher education. Do men and women differ? Current Psychology 2017, 36, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2013, 25, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobasa, S.C. Stressful life events, personality, and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality Social Psychology 1979, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.-L. Are you tired? Spillover and crossover effects of emotional exhaustion on the family domain. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 2015, 18, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Business and Psychology 2019, 34, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. Hardiness: The courage to grow from stresses. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2006, 1, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Hine, D.W. Development and validation of the uncivil workplace behavior questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2005, 10, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, R.; Arnold, D.H.; Fratzl, J.; Thomas, R. Workplace bullying in academia: A Canadian study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 2008, 20, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milam, A.C.; Spitzmueller, C.; Penney, L.M. Investigating individual differences among targets of workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2009, 14, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, K.; Settles, I.H.; Pratt-Hyatt, J.; Brady, C.C. Experiencing incivility in organizations: The buffering effects of emotional and organizational support. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2012, 42, 340–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.W.; Hur, W.M. Emotional intelligence, emotional exhaustion, and job performance. Social Behavior and Personality 2011, 39, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Foulk, T.; Erez, A. How incivility hijacks performance: It robs cognitive resources, increases dysfunctional behavior, and infects team dynamics and functioning. Organizational Dynamics 2015, 44, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, P.; Sambasivan, M.; Kumar, N. Counterproductive work behavior among frontline government employees: Role of personality, emotional intelligence, affectivity, emotional labor, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2016, 32, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Kim, M. The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of self-efficacy and compassion at work: The job demands-resources (JD-R) approach. Journal of Business and Psychology 2016, 32, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K.; Jex, S.M. Coworker incivility and incivility targets’ work effort and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating role of supervisor social support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2012, 17, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2016, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; Leavitt, K.; Lim, S. Incivility hates company: Shared incivility attenuates rumination, stress, and psychological withdrawal by reducing self-blame. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2016, 133, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, F. Relationships between teacher organizational commitment, psychological hardiness and some demographic variables in Turkish primary schools. Journal of Educational Administration 2009, 47, 630–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhang, S.; Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Dong, X.; Sun, T.; Fan, L. Impact of workplace incivility against new nurses on job burn-out: A cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soomro, A.A.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Shah, S.A.M. Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. South Asian Journal of Business Studies 2018, 7, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 1991, 110, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totterdell, P.; Hershcovis, M.S.; Niven, K.; Reich, T.C.; Stride, C. Can employees be emotionally drained by witnessing unpleasant interactions between coworkers? A diary study of induced emotion regulation. Work & Stress 2012, 26, 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Viotti, S.; Essenmacher, L.; Hamblin, L.E.; Arnetz, J.E. Testing the reciprocal associations among co-worker incivility, organizational inefficiency, and work-related exhaustion: A one-year, cross-lagged Study. Work Stress 2018, 32, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Westman, M. The relationship between stress and performance: The moderating effect of hardiness. Human Performance 1990, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management 1991, 13, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 1998, 83, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassour-Borochowitz, D.; Desivillia, H. Incivility between students and faculty in an Israeli college: A description of the phenomenon. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 2016, 28, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Zabrodska, K.; Kveton, P. Prevalence and forms of workplace bullying among university employees. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 2013, 25, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).