1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic is projected to considerably impact worldwide trade due to its complex implications on supply chains and other economic and financial problems. The global economy has suffered significantly as a result of the lockdown to control the spread of the virus. The world economy is anticipated to contract by -3% in 2020, according to the IMF's World Economic Outlook for April 2020 (Hayakawa & Mukunoki, 2021). Global economic development is being significantly impacted by the infection epidemic. The virus is anticipated to decrease global economic growth by more than 2.0% per month if the current trend continues (Verma et al., 2021). The ongoing economic destruction will continue to have an impact on the global economy by obstructing trade and production (Baldwin & Tomiura, 2020).

The pandemic has significantly damaged global supply chains. Significant setbacks have been experienced in the performance of the finances, lead times, customers, and manufacturing. It caused a problem that impacts both supply and demand, making it more challenging to effectively respond. The initial shock was on the supply side. Then, as containment measures were put in place, demand significantly increased (Fonseca & Azevedo, 2020). Unlike prior epidemics, this pandemic has simultaneously afflicted every node (supply chain member) and edge in a supply chain (Gunessee & Subramanian, 2020; Paul & Chowdhury, 2020). The flow of the supply chain has been considerably disrupted as a result. The capacity of supply, transportation, and production are all constrained by several factors such as border closures, supply market restrictions, obstructions to vehicle and commerce movements, a lack of labor, and the maintenance of physical separation in manufacturing facilities (Amankwah-Amoah, 2020; Paul et al., 2021). The pandemic has had a big impact on global trade due to the disruption of the global supply chain.

Due to the lockdown and shutdown scenarios, Bangladesh is dealing with several unanticipated issues that affect the economy, trade, education, industry, politics, and everyday life of its citizens. The country's GDP is predicted to be lower than in previous years, and the poverty rate has increased dramatically. Over the past ten years, Bangladesh's GDP has grown at a remarkable rate, with an annual growth rate of 7.9% in 2019. Due to economic downturns brought on by COVID-19 economic lockdowns, Bangladesh's GDP is predicted to fall to 2% in 2020 (IMF, 2020). Bangladesh's socioeconomic growth will slow down by June 2020. As a result of increased pandemic-related spending on health, education, infrastructure, and social protection combined with the nation's deteriorating economic situation, Bangladesh's external debt-to-GDP ratio is predicted to increase from 36 percent at the end of 2019 to approximately 41 percent. Because most businesses have stopped hiring to cut operating costs, the pandemic reduces work opportunities and increases Bangladesh's graduate unemployment rate (SHAHRIAR et al., 2021).

As the COVID-19 outbreak forces countries to close borders, it poses a threat to more than just one country's health and has the potential to have a negative social, political, psychological, and economic impact on the entire world. This outbreak also disrupts educational institutions, tourism, investment, export, and imports (Hassani & Shahwali, 2020). The pandemic has had a significant economic impact on all sectors and all firms of different sizes, at different degrees of capacity utilization, and under various scenarios of the total, protracted, and partial lockdown. Ready-made garments (RMG), the largest exporting sector in Bangladesh, experienced negative growth (-5.5%) in the first eight months of FY 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. All important export items— except jute and jute products—saw negative growth in the first eight months of FY 2020. Real export earnings this fiscal year may be lower than in FY 2019 due to the obvious failure to achieve the ambitious export growth target of 12% for FY 2020 (BBS, 2020).

On the other hand, import payments have grown at a negative rate (-2.2 percent growth in the first seven months of FY 2020). The performance of the import sector points to an economy that is experiencing a fall in demand, which would hurt growth in FY 2020. In terms of import payments, import sub-components such as capital goods (-8.3%), including capital machinery (-22.0%), and intermediate inputs (-2.1%) had negative growth in the first half of FY 2020 compared to the same time in FY 2019. (Rahman et al., 2020). With a combined employment rate of 60% and a 32% contribution to Bangladesh's GDP, agriculture and industry dominate local trade in that country (BBS, 2020).

It is obvious that the Covid-19 pandemic negatively impacted the trade of Bangladesh in two ways. First, it created a demand shock in the national and international markets due to the reduced demand which is the result of lower income of the people during the pandemic. During the pandemic, local trade in Bangladesh has been badly harmed by several concerns, such as employment losses in the sector (especially in ready-made garment factories), and declining consumer demand as a result of falling industry wages. Moreover, Ready-Made-Garments (RMG) is the principal source of foreign exchange earnings of Bangladesh and it constitutes 85% of the total export earnings. The USA and the EU are the main export markets of Bangladesh and they constitute almost two-thirds of RMG export. The Covid-19 pandemic has drastically impacted the USA, the EU, and other developed economies and substantially reduced the demand for goods and services in the global market due to the lower income caused by the job loss during the pandemic (Raihan, 2020).

Second, the pandemic impacted trade through supply shocks caused by trade disruptions arising from higher trade costs and disruptions of global supply chains. The lockdown policy to control the spread of the virus has significantly disrupted global communication and supply chains that made international trade costly and difficult. Bangladesh is an export-oriented country and a large share of its export industries, more especially the RMG sector, is import-based. Thus trade disruptions critically affected the export and import of Bangladesh.

However, the crucial research question is whether Bangladesh perform well in international trade during Covid-19 despite the different shocks posed by the pandemic. This study attempts to analyze the trade performance of Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first identifies the trade scenarios of Bangladesh during the pandemic with descriptive data. It then applies a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model using the GTAP database to find out the simulated trade scenario in different sectors under different level shocks caused by the pandemic. Finally, the study analyzes the effects of different levels of demand shock and trade disruptions caused by trade costs due to the Covid-19 pandemic on export and import during the pandemic and compare with the actual data and provide policy suggestions on trade performance of Bangladesh during the pandemic.

The remainder of the study is arranged as follows. The next section discusses the relevant literature and identifies the research gap. Section three describes the methodology, software packages, and data used in the study. Section four discusses the analysis results. The last section makes conclusions and provides policy directions.

2. Literature review

Theoretically, COVID-19 is likely to have a big impact on global trade in several different ways. An exporting nation's increased COVID-19 load inevitably shrinks the size of the industry, which lowers export supply. Exports will decline, particularly in fields and nations where working remotely is impractical. A commodity's domestic demand as well as production may be affected by the COVID-19 load. Redirecting the amount not consumed at home to the export market can result in a net rise in exports if the decline in domestic demand outweighs the decline in output. In an economy that imports goods, the burden of COVID-19 is mostly felt due to a decline in aggregate demand. As a result of decreased incomes and fewer retail store visits, demand will decline. The short-term impact of COVID-19 on global poverty was calculated by Sumner et al. (2020). Each scenario's effect on the number of people living in poverty is calculated using the global poverty standards of $1.90, $3.20, and $5.50 per day. Because poverty levels increased after the epidemic in 1990, the outcome conflicts with the UN Sustainable Development Goal (UNSDG), which states that poverty would be almost entirely eradicated by 2030.

Chowdhury et al. (2020) made a case study on how to manage the COVID-19 pandemic's effects on the food and beverage industry. This study found that while the medium-to-long-term implications of this pandemic appear to be complex and uncertain, the short-term effects, such as product expiration, a shortage of operational capital, and restricted distributor activities, are severe. Numerous performance indicators, including firm return on investment, GDP contribution, and workforce size, are all expected to worsen with time. Additionally, companies might need to change the relationships they have with their distributors and trading partners as well as their supply chain.

IMF (2020) predicted that real GDP growth would be 3% globally and 6% in the US, making 2020 the worst recession since the Great Depression. Both agricultural trade and general international trade will be significantly impacted. The WTO has forecast a range of 13% to 32% for the potential loss in overall trade volume, but because of falling prices, it is likely to be significantly worse in value terms. Hassani and Shahwali (2020) conducted a thorough analysis of 42 countries using the computable general equilibrium (CGE) model and found that the pandemic will result in a 905 billion dollar decline in world trade. The scenario of prolonged containment will result in a $2,095 billion reduction in world trade.

According to Hayakawa and Mukunoki (2021), the COVID-19 burden has a significant negative impact on trade in exporting countries but not in importing ones. Exports from developing countries are negatively impacted by exporters' COVID-19 burden, but not those from wealthy nations. They further argued that an exporter benefits from the burden of COVID-19 in its neighboring countries. Importers' COVID-19 load benefits trade in the agricultural sector, but exporters' COVID-19 burden hurts it, particularly in the textile, footwear, and plastics sectors. Dhinakaran and Kesavan (2020) discussed the stagnation of India's exports and imports during COVID-19. The authors concluded that during the COVID-19 shutdown, India's export and import declined. Following the COVID-19 shutdown, the national and state governments of India must deal with several social, economic, political, and institutional issues.

Maliszewska et al. (2020) assessed the likely effect of COVID-19 on GDP and trade using a standard global computable general equilibrium model. The study suggested that the pandemic causes a 2% decline in GDP worldwide, a 2.5% decline in poor countries, and a 1.8% decline in industrialized ones. In an improved pandemic scenario where containment is anticipated to take longer and now seems more likely, the declines are almost 4% lower than the global average. The output of pandemic-affected home services as well as traded tourism services show the highest negative shock. According to Gruszczynski (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic's effects are most palpable in the global services sector. The main losers are international tourism, passenger air travel, and container transportation. Both international financial transactions and the use of information and communication technology services have sharply declined.

Barichello (2020) predicted that trade in agricultural products will be less impacted in Canada because of its relatively low-income elasticity of demand. However, it is reasonable to expect a 12%–20% fall in the actual transaction value. Grain exports will be the least impacted among agricultural exports, but Canada can be expected to take part. Canada will have the best chances in the grains group because it has the lowest income elasticity. Furthermore, the Canadian wheat business will profit if more widespread export restrictions are implemented, such as those for wheat. Livestock, pulses, and horticulture are predicted to have a bigger trade decline because of the significant loss of purchasing power in many importer nations.

Islam and Fatema (2023) argued that the Covid-19 pandemic affected business and trade through two different channels such as supply shock due to the disruptions of global supply chains and demand shock due to the lower income of the people caused by job losses. The pandemic is projected to have a considerable impact on worldwide trade due to its complex implications on supply chains and other economic and financial problems (Chowdhury et al., 2021; Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). A rise in imports from other nations may result from this decline in trade prices. On the other hand, negative production shocks brought on by COVID-19 in one country may reduce production in other nations via supply-chain networks (Hayakawa & Mukunoki, 2021). The pandemic has had a significant impact on the world's supply chain since the only way to effectively stop the virus from spreading is to impose a rigorous lockdown that restricts people's movement (ADB, 2020). In addition, the pandemic has reduced output since demand has decreased as a result of lockdowns and other emergency measures. Demand has been impacted by consumers' hesitation to spend money right now all across the world. This phenomenon can be explained by greater uncertainty and a generalized fear of losing money (due, for instance, to unemployment).

According to Zayed et al. (2021), international trade will suffer during a pandemic because there will be less demand for goods and services on a global scale. The travel, tourism, and building industries would all suffer as a result. The world's reserves of commodities and supply chain may be in danger. Both the governmental and commercial sectors in emerging nations may be able to grow their debt due to the accessibility of low-interest loans. The COVID-19 tragedy will hurt the world economy.

Segal and Gerstel (2020) argued that the growth of COVID-19 interferes with government commitments and the supply chain. The virus worsens economic uncertainty, as the financial crisis of 2008 demonstrated. Due to COVID-19's effects on the Chinese economy, automobile sales in January and February were reduced by a record 80 percent and exports by 17.2 percent. The global COVID-19 epidemic is predicted to cause a 1.5 percentage point slowdown in the global economy in 2020. The social distancing motto will pose problems for tourism and travel-related companies. The manufacturing sector will suffer as a result.

According to Liu et al. (2021), a country's imports from China were significantly reduced by its own Covid-19 deaths and lockdowns. They suggested that the pandemic's negative effects on demand outnumbered those on supply. However, Covid-19 deaths in a nation's main trading partners (apart from China) lead to an increase in imports from China, somewhat offsetting the nation’s effects. They also considered how the pandemic would affect China's exports to the world and its purchases from the world in 2020 and concluded that the path of causation is not linear. Instead, several aspects of the pandemic are likely to have an impact on international trade, including its direct health impact and the behavioral changes that result in the affected countries, the effects of the government's measures to stop the virus's spread, and the effects in third countries as a result of the pandemic's impact there.

Evenett et al. (2022) conducted a study on trade policy remedies for the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. A descriptive evaluation of the trade policy responses to the COVID-19 epidemic is what this article aims to do. The analysis discovered significant country-level heterogeneity in both the use of trade policy and the sorts of measures adopted. A few nations took steps to limit exports and ease imports, while others focused exclusively on one of these margins, and a large number did not utilize trade policy at all. The observed variability raises several research concerns about the factors that led to trade policy responses to COVID-19, how these measures affected trade and the pricing of important goods, and about how trade agreements affected the use of trade policy.

The above discussion on literature shows that several studies anticipated the potential impact of COVID-19 on global trade as well as the trade in different sectors of a specific country or group of countries. It should be crucial to identify the simulated effect of the pandemic on trade and to compare the potential effect and actual performance of a country. As the economy of Bangladesh is highly dependent on trade, it is a probable simulated effect of COVID-19 on its trade and makes a comparison with the actual trade performance of the country to provide the actual trade performance scenario.

A descriptive analysis of the macroeconomic effects of Covid-19 on Bangladesh was done by Ahamed (2021). They argued that although the economy was not in danger as a result of the immediate economic shock of COVID-19, long-term shockwaves from global uncertainty can be very harmful. An integrated macroeconomic framework architecture is crucial for the economy since the shock in the informal sectors is difficult to understand. Policymakers need to be aware of the circumstance and take decisive action. Kumar and Nafi (2020) found that Bangladesh has experienced an adverse impact on inbound and outbound tourism. The intensification of COVID-19is predicted to cause a long-term adverse impact on tourism in Bangladesh. Alam et al. (2020) argued that the magnitude of the economic losses of the pandemic in Bangladesh will depend on how the outbreak evolves as any pandemic disease and its economic consequences are vastly ambiguous which makes it challenging for policymakers to work out an axiomatic and appropriate macroeconomic policy guideline.

However, none of the studies focused on identifying the potential effect of COVID-19 on the trade performance of Bangladesh caused by the demand stick and trade disruptions due to higher trade costs resulting from the pandemic. This study attempts to fill up this above-mentioned research gap. It identifies the trade scenarios during the pandemic with descriptive data, the simulated trade scenario in different sectors under different level shocks caused by COVID-19 using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model using the GTAP database. It finally analyzes the effects of different levels of demand shock and trade disruptions caused by trade costs due to the Covid-19 pandemic on export and import during the pandemic and compares them with the actual data.

3. Methodology

The analysis of this study was done on three different levels such as descriptive analysis showing the trade scenario of Bangladesh during the pandemic, applying the CGE model using the GTAP database to identify the effects of different levels of demand shock and trade disruptions caused by trade cost on export and import during the pandemic, and to find out the actual trade performance by comparing the actual data with the CGE simulated results. Based on some previous studies such as ADB (2020) and Maliszewska et al. (2020), this study applies the CGE model approach using two different shocks such as demand shock resulting from reduced household consumption and trade disruptions caused by higher yardage costs during the pandemic. Moreover, studies such as ADB (2020); Maliszewska et al. (2020); and Rahman et al. (2020) assumed that the Covid-19 pandemic may cause shocks at different levels depending on the severity and longevity of the pandemic. The proposed shocks are in three different scenarios as low, medium, and high shocks. As proposed by the previous studies, this study assumed private consumption (as a proxy to demand shock) to be declined by 2%, 3.5%, and 5% under the low, medium, and high shock scenarios and trade costs (as a proxy to trade disruptions) rose by 1.5%, 2.5% and 5% in the low, medium, and high shock scenarios respectively.

To quantify the effects of demand shock and trade disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic on the export, import, and domestic output of Bangladesh the study applies computable general equilibrium (CGE) using the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) to assess the effects of demand shock and trade disruptions on all sectors of the Bangladesh economy. Among the quantitative methods of trade policy analysis, the GTAP model is widely used as this mode tackles the economic issues not only in different sectors and regions but also among different factors of production (Qi & Zhang, 2018). Several studies used the GTAP model to analyze the effects of bilateral and multi-lateral trade policy changes (Khoso et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2003). As argued by Lloyd and Maclaren (2004), the popularity of using CGE models to undertake empirical research, especially in Australia is understandable for its multinational scope and broader coverage over a variety of industries. The study uses the latest GTAP version 10 which has the latest updated database. It is a multi-sector and multi-region CGE model with an updated database of 141 regions and 61 sectors and five factors of production for each region. Although The GTAP database provides several reference years such as 2004, 2007, 2011and 2014 the GTAP 10 uses the latest reference year 2014.

The GTAP model is aggregated by 141 regions, 65 sectors, and 8 factors of production. In this study, we aggregated the regions into four new regions i.e., Bangladesh, China, ASEAN, and the rest of the world. All 65 sectors are aggregated into seven sectors as reported in Table 2. We divided the factors of production into four types such as land, labor, capital, and natural resources as described in Table 3. Finally, in the GTAP CGE simulation, this study assumed private consumption (as a proxy to demand shock) and trade costs (as a proxy to trade disruptions) under the low, medium, and high shock scenarios. The solution algorithm used is the Johansen method with automatic correctness to obtain a high level of accuracy in the results.

Table 1.

Sector Aggregation.

Table 1.

Sector Aggregation.

| Sector |

Comprising |

| Textiles |

Textiles |

| Apparel |

RMG Products |

| Leather |

Leather |

| Fish |

Fish |

| othermnf |

All other manufacturing |

| Service |

All services |

| AgriFood |

All Agriculture and Food Products |

Table 2.

Region Aggregation.

Table 2.

Region Aggregation.

| Region |

Comprising |

| Bangladesh |

Bangladesh |

| South Asia |

All South Asian countries excluding Bangladesh |

| Rest of World |

Countries from the Rest of the World |

Table 3.

Factor Aggregation.

Table 3.

Factor Aggregation.

| Factor |

Comprising |

| Land |

Land |

| Capital |

Capital |

| NatRes |

Natural resources |

| Labor |

Technicians/Assoc Professional; Clerks; Service/Shop workers; Officials and Managers; Agricultural and Unskilled |

4. Analysis and Findings

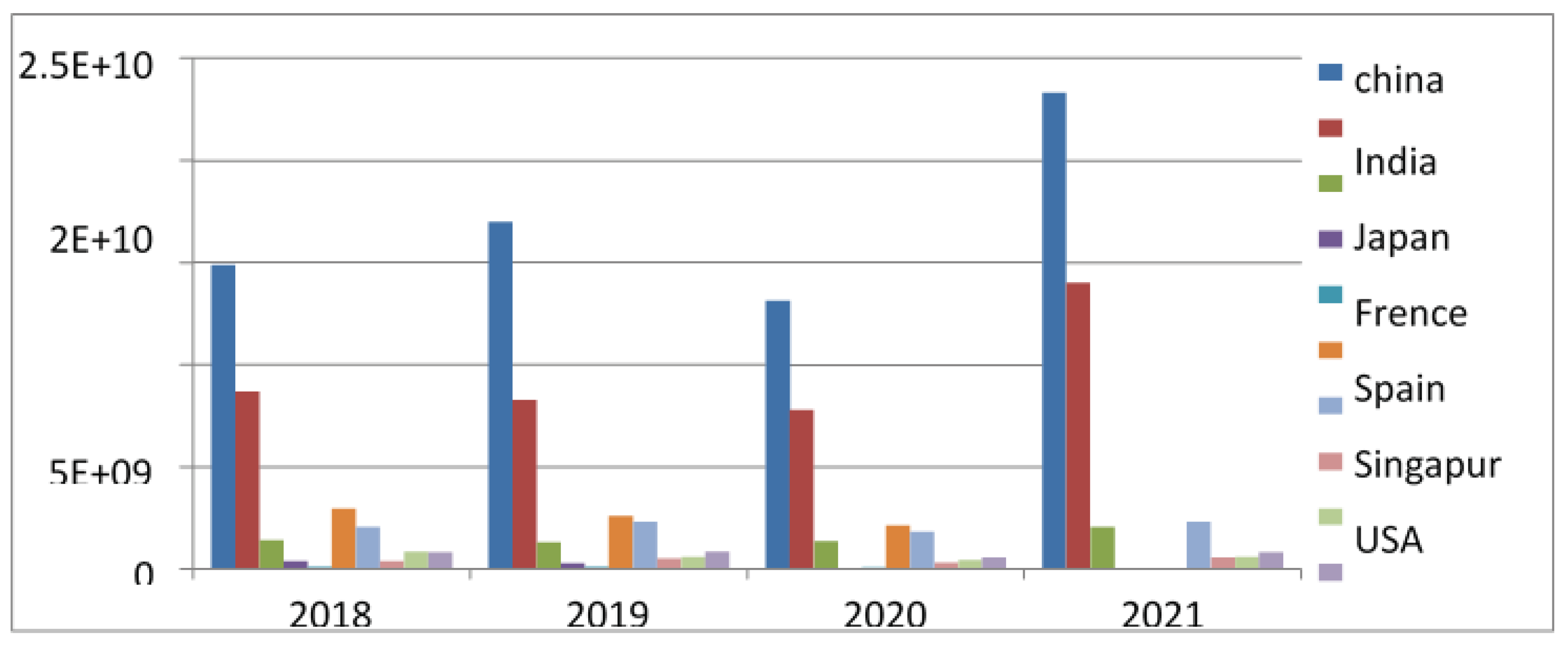

Figure 1 shows the yearly imports of Bangladesh with major trading countries in billion dollars. It shows that China is the largest importing country of Bangladesh. In 2018 and 2019 the total value of imports respectively were US

$1.489 billion and US

$1.702 billion. In 2020 the value of imports was US

$1.3148 and in 2021 US

$2.331 billion. Here we can see that the value of imports in 2019 is higher than the 2018 but during the COVID-19 period in 2020, the value of imports decrease. But in 2021 it has again increased. Therefore the highest increase in 2021. India is the second largest importing country of Bangladesh. From this figure, we can see that during the COVID-19 period in 2020, the value of imports was US

$7.818 billion which was respectively lower than the previous year. But in 2021 it increased again. Bangladesh also imports from the USA, Japan, and Singapore. Imports from Singapore in 2018 and 2019 were US

$2.960 billion and US

$2.585 billion As a result of COVID-19 the value of imports in 2019 decreased in this period the total value of imports was US

$2.121 billion and there are no imports in 2021. Fewer amounts of imports from the UK, France, Germany, and Italy. But as a result of COVID-19 during 2020-2021 there are no imports from France.

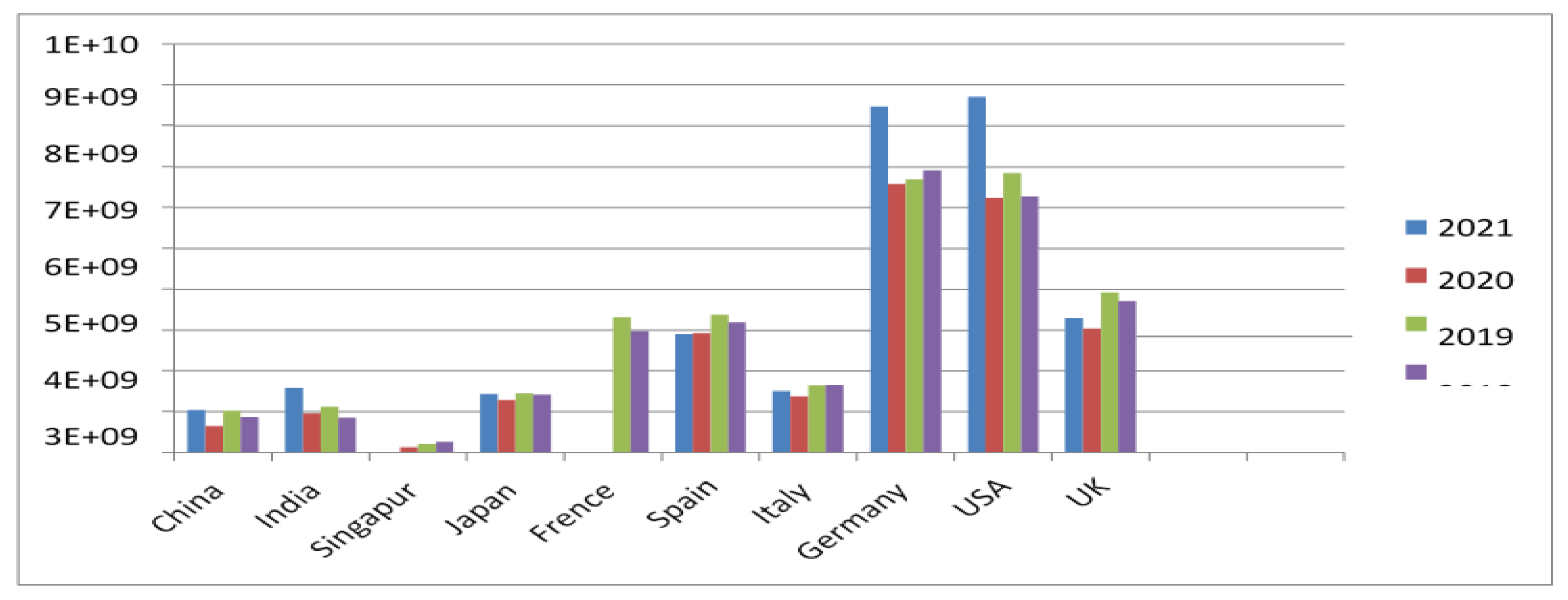

Figure 2 shows that the United States is the largest exporter of Bangladesh. In 2018 and 2019 the total value of exports respectively were US

$6.266 billion and US

$6.849 billion which is higher than the privies year. But in 2020 the value of exports decreased by US

$6.0531 billion. But a positive aspect is that over time the country's export ability increased in 2021 it has again increased to US

$2,463,703,072. Therefore the highest increase in 2021. Germany is the second largest exporting country of Bangladesh. From this figure, we can see that during the COVID-19 period in 2020, the value of exports was US

$65.71 billion which was respectively lower than the previous year. But in 2021 it increased again. In 2021 the exports were US

$84.75 billion which was higher than the previous year 2020. It is a positive aspect for Bangladesh that Bangladesh overcomes the COVID-19 situation. The UK is another exporting country of Bangladesh. In 2019 the value of exports from Bangladesh to the UK was US

$3.918 billion which was higher than in 2018. But in 2020 during the COVID-19situation, the export rate was US

$3.045 billion which was lower than in 2019. In 2020 the export volume increased more than in 2019 but it was also lower than the 2018 and 2019. France is also an important exporting country of Bangladesh but in 2020 during COVID-19 Bangladesh's exports to France are most affected because there are no exports with them in 2020-21.

Bangladesh also imports from the USA, Japan, and Singapore. Imports from Singapore in 2018 and 2019 were US $2960152330 and US $2585770593 As a result of COVID-19 the value of imports in 2019 decreased in this period the total value of imports was US $2121037605 and there are no imports in 2021. Fewer amounts of imports from the UK, France, Germany, and Italy. But as a result of COVID-19 during 2020-2021 there are no imports from France.

The CGE model analyses the effect of private consumption demand shock and trade shock caused by higher costs during the pandemic at low, medium, and high levels of shock. The study measures the effects of both shocks separately as well as combined using the GTAP database. Both of the shocks are assumed to occur at low, medium, and high-level shocks.

Table 1.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the low level (1.5%).

Table 1.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the low level (1.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

1160.66 |

-1.17 |

10183.38 |

10195.1 |

11.72 |

10600.07 |

10606.87 |

6.8 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

28021.78 |

2.59 |

458.75 |

460.05 |

1.3 |

28400.34 |

28403.24 |

2.89 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1120.67 |

-0.98 |

491.98 |

493.83 |

1.85 |

2659.22 |

2661.49 |

2.26 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

79.52 |

0.08 |

70.07 |

70.3 |

0.22 |

10673.92 |

10692.33 |

18.41 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

828.91 |

-4.09 |

26599.27 |

26623.04 |

23.78 |

33599.28 |

33563.96 |

-35.32 |

| Service |

316.74 |

316.09 |

-0.64 |

2569.56 |

2573.39 |

3.82 |

173314 |

173225.6 |

-88.34 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1520.7 |

-0.96 |

8280.74 |

8302.79 |

22.05 |

75094.27 |

75225.09 |

130.82 |

Table 2.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the medium level (2.5%).

Table 2.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the medium level (2.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

1159.1 |

-2.73 |

10183.38 |

10210.72 |

27.34 |

10600.07 |

10615.94 |

15.88 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

28025.23 |

6.04 |

458.75 |

461.79 |

3.04 |

28400.34 |

28407.09 |

6.75 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1119.36 |

-2.29 |

491.98 |

496.3 |

4.32 |

2659.22 |

2664.5 |

5.28 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

79.63 |

0.19 |

70.07 |

70.59 |

0.52 |

10673.92 |

10716.87 |

42.95 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

823.46 |

-9.53 |

26599.27 |

26654.74 |

55.48 |

33599.28 |

33516.88 |

-82.4 |

| Service |

316.74 |

315.23 |

-1.5 |

2569.56 |

2578.49 |

8.92 |

173314 |

173107.8 |

-206.14 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1519.41 |

-2.25 |

8280.74 |

8332.19 |

51.45 |

75094.27 |

75399.51 |

305.24 |

Table 3.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the high level (5%).

Table 3.

Trade effects due to fall in domestic household consumption during Covid-19 (demand shock) at the high level (5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

1157.93 |

-3.9 |

10183.38 |

10222.44 |

39.06 |

10600.07 |

10622.75 |

22.68 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

28027.82 |

8.63 |

458.75 |

463.09 |

4.34 |

28400.34 |

28409.98 |

9.64 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1118.38 |

-3.27 |

491.98 |

498.15 |

6.17 |

2659.22 |

2666.77 |

7.54 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

79.72 |

0.27 |

70.07 |

70.82 |

0.74 |

10673.92 |

10735.28 |

61.36 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

819.37 |

-13.62 |

26599.27 |

26678.52 |

79.25 |

33599.28 |

33481.57 |

-117.71 |

| Service |

316.74 |

314.59 |

-2.15 |

2569.56 |

2582.31 |

12.75 |

173314 |

173019.5 |

-294.48 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1518.45 |

-3.21 |

8280.74 |

8354.24 |

73.5 |

75094.27 |

75530.33 |

436.06 |

Table 1 summarizes CGE analysis results for demand shock at a low level. The analysis results suggest that a low-level demand shock (1.5%) reduced the exports of all sectors except for apparel and fish. The highest reduction occurs in the other manufacturing sector ($40.9m) followed by textiles ($1.17m) whereas the apparel sector’s export will rise by $2.59m followed by a small volume increase in the fishing sector.

In the case of imports, the analysis results suggest that despite the negative domestic demand shock caused by the pandemic the import value of different sectors increases with the highest increase in other manufacturing sectors ($23.78m) followed by agriculture and food ($22.05m) and textiles ($11.72m). The effects of demand shocks on domestic output are also critical. The demand shock induced by the Covid-19 pandemic reduces domestic output in service ($88.34m) and other manufacturing sectors ($35.32m) whereas the output of the others sector increase. The agriculture and food sector experienced the highest increase in output by $130.82m) followed by the fish and apparel sectors. The CGE model determines the effects of shock at three different levels on the trade performances of Bangladesh. The analysis results at medium and high-level shocks suggest that the higher level of shocks will have a higher impact on the export, import, and domestic output.

Tables 4–6 summarizes the CGE analysis results of trade disruptions caused by higher trade costs due to the Covid-19 pandemic at low, medium, and high level respectively. The analysis results indicate that trade disruptions substantially reduce both the export and import of all sectors in Bangladesh. The apparel sector incurs the highest fall in export value ($2702.89m) followed by textiles ($164.63m) and agriculture and food ($114.39m). The negative effect of trade disruptions on the exports of other sectors is comparatively lower.

Table 4.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at a low level (1.5%).

Table 4.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at a low level (1.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

997.2 |

-164.63 |

10183.38 |

9239.47 |

-943.9 |

10600.07 |

10379.62 |

-220.44 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

25316.3 |

-2702.89 |

458.75 |

430.97 |

-27.78 |

28400.34 |

25701.7 |

-2698.65 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1029.41 |

-92.23 |

491.98 |

447.12 |

-44.86 |

2659.22 |

2599.48 |

-59.75 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

76.55 |

-2.89 |

70.07 |

68.32 |

-1.75 |

10673.92 |

10669.58 |

-4.33 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

780.79 |

-52.21 |

26599.27 |

25273.74 |

-1325.52 |

33599.28 |

35443.21 |

1843.93 |

| Service |

316.74 |

295.39 |

-21.34 |

2569.56 |

2449.61 |

-119.95 |

173314 |

174044 |

730 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1407.27 |

-114.39 |

8280.74 |

7853.16 |

-427.58 |

75094.27 |

75433.23 |

338.96 |

Table 5.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at the medium level (2.5%).

Table 5.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at the medium level (2.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

887.45 |

-274.38 |

10183.38 |

8610.2 |

-1573.17 |

10600.07 |

10232.66 |

-367.41 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

23514.38 |

-4504.81 |

458.75 |

412.44 |

-46.31 |

28400.34 |

23902.6 |

-4497.75 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

967.93 |

-153.72 |

491.98 |

417.22 |

-74.76 |

2659.22 |

2559.64 |

-99.58 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

74.63 |

-4.82 |

70.07 |

67.15 |

-2.92 |

10673.92 |

10666.7 |

-7.22 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

745.98 |

-87.01 |

26599.27 |

24390.06 |

-2209.21 |

33599.28 |

36672.5 |

3073.22 |

| Service |

316.74 |

281.16 |

-35.57 |

2569.56 |

2369.64 |

-199.92 |

173314 |

174530.7 |

1216.67 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1331 |

-190.66 |

8280.74 |

7568.11 |

-712.63 |

75094.27 |

75659.2 |

564.94 |

Table 6.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at a high level (5%).

Table 6.

Trade effects due to trade disruptions during Covid-19 (trade costs) at a high level (5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

613.06 |

-548.77 |

10183.38 |

7037.03 |

-3146.35 |

10600.07 |

9865.25 |

-734.81 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

19009.56 |

-9009.63 |

458.75 |

366.14 |

-92.61 |

28400.34 |

19404.85 |

-8995.49 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

814.2 |

-307.44 |

491.98 |

342.45 |

-149.53 |

2659.22 |

2460.07 |

-199.16 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

69.81 |

-9.63 |

70.07 |

64.23 |

-5.84 |

10673.92 |

10659.48 |

-14.44 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

658.97 |

-174.02 |

26599.27 |

22180.86 |

-4418.41 |

33599.28 |

39745.73 |

6146.45 |

| Service |

316.74 |

245.59 |

-71.14 |

2569.56 |

2169.72 |

-399.84 |

173314 |

175747.3 |

2433.34 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1140.35 |

-381.31 |

8280.74 |

6855.48 |

-1425.26 |

75094.27 |

76224.15 |

1129.88 |

In the case of imports, the effects of trade disruptions caused by the pandemic in Bangladesh are highest for other manufacturing sectors ($1325.52m) followed by textiles ($943.9m), Agri & food ($427.58m), and service ($119.95m) sectors. The results suggest that the effects of the trade disruptions on export and imports are higher in the sectors that have higher export and import values compared to the other sectors. The effects of trade disruptions on domestic output are also obvious. The trade disruptions reduce domestics output in apparel ($2698.65m), textiles ($220.44m), leather ($59.75m), and fish ($4.33m) sectors whereas increases the domestic output in other manufacturing ($1843.93m), service ($730m), and Agri & food ($338.96m) sectors. The CGE analysis results at medium and high-level shocks suggest that the effects of trade disruptions intensify as the level of shocks increases.

The CGE model also analyses the combined effects of both demand shock and trade disruptions on the trade performance of Bangladesh and the analysis results are summarized in Tables 7–9. The analysis results indicate that the combined effects of both demand shock and trade disruptions are higher than their individual effects in all sectors in Bangladesh. Finally, the study analyses the actual exports and imports of different sectors during and post-pandemic periods to cross-validate the simulated effects of the shocks using the CGE model. The export data summarized in Tables 10 and 11 suggest that the export performance of different sectors of Bangladesh during the pandemic is mixed. The export performance of the textiles sector during the pandemic is good enough. Although CGE simulated analysis shows that the export of the textiles sector will reduce substantially, the actual data shows an increase in textiles export of Bangladesh in 2020 by $124.16m. The apparel sector experience a high decrease in exports ($5372.64m) which is also supported by the results of the simulated analysis. It infers the export of the apparel sector in Bangladesh is substantially affected by the shocks during the Covid-19 pandemic. Other sectors that are highly impacted by the pandemic are service and other manufacturing sectors. These sectors experience a very high fall in export value compared to the fall of exports in these sectors suggested by the CGE simulation results. Agri and food sectors performed well during the pandemic. The fall in export of these sectors is low compared to the decrease suggested by the CGE analysis.

Table 7.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at a low level (1.5%).

Table 7.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at a low level (1.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

991.47 |

-170.37 |

10183.38 |

9214.95 |

-968.43 |

10600.07 |

10357 |

-243.07 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

25164.89 |

-2854.3 |

458.75 |

432.1 |

-26.65 |

28400.34 |

25549.66 |

-2850.68 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1021.69 |

-99.95 |

491.98 |

449.19 |

-42.79 |

2659.22 |

2594.53 |

-64.69 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

75.72 |

-3.72 |

70.07 |

68.87 |

-1.21 |

10673.92 |

10687.8 |

13.89 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

774.66 |

-58.33 |

26599.27 |

25343.34 |

-1255.92 |

33599.28 |

35404.32 |

1805.04 |

| Service |

316.74 |

294.1 |

-22.63 |

2569.56 |

2455.95 |

-113.61 |

173314 |

174077.7 |

763.72 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1397.15 |

-124.51 |

8280.74 |

7887.39 |

-393.35 |

75094.27 |

75545.6 |

451.34 |

Table 8.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at the medium level (2.5%).

Table 8.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at the medium level (2.5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

874.06 |

-287.77 |

10183.38 |

8552.98 |

-1630.4 |

10600.07 |

10179.87 |

-420.2 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

23161.08 |

-4858.11 |

458.75 |

415.09 |

-43.66 |

28400.34 |

23547.86 |

-4852.49 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

949.91 |

-171.73 |

491.98 |

422.05 |

-69.93 |

2659.22 |

2548.1 |

-111.12 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

72.69 |

-6.75 |

70.07 |

68.42 |

-1.65 |

10673.92 |

10709.2 |

35.29 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

731.68 |

-101.31 |

26599.27 |

24552.46 |

-2046.81 |

33599.28 |

36581.76 |

2982.48 |

| Service |

316.74 |

278.15 |

-38.58 |

2569.56 |

2384.44 |

-185.13 |

173314 |

174609.3 |

1295.34 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1307.41 |

-214.26 |

8280.74 |

7647.98 |

-632.76 |

75094.27 |

75921.41 |

827.15 |

Table 9.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at a high level (5%).

Table 9.

Trade effects due to both demand shock and trade disruptions during Covid-19 at a high level (5%).

| Sectors |

Value of Exports(qxw) |

Value of Imports (qim) |

Domestic output (qo) |

| Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

| Textiles |

1161.83 |

1114.33 |

-47.51 |

10183.38 |

9972.33 |

-211.04 |

10600.07 |

10453.71 |

-146.35 |

| Apparel |

28019.19 |

27022.25 |

-996.94 |

458.75 |

462.08 |

3.33 |

28400.34 |

27399.74 |

-1000.61 |

| Leather |

1121.65 |

1075.17 |

-46.47 |

491.98 |

499.1 |

7.12 |

2659.22 |

2625.98 |

-33.24 |

| Fish |

79.44 |

74.79 |

-4.66 |

70.07 |

71.38 |

1.3 |

10673.92 |

10755.34 |

81.43 |

| Other Manufacturing |

832.99 |

791.18 |

-41.81 |

26599.27 |

26835.81 |

236.54 |

33599.28 |

33527.24 |

-72.04 |

| Service |

316.74 |

309.73 |

-7 |

2569.56 |

2606.8 |

37.24 |

173314 |

173615.3 |

301.31 |

| Agri & Food |

1521.66 |

1457.99 |

-63.67 |

8280.74 |

8380.64 |

99.9 |

75094.27 |

75630.93 |

536.66 |

Table 10.

Export performance of Bangladesh during Covid-19.

Table 10.

Export performance of Bangladesh during Covid-19.

| Sectors |

Import ( Million US$) |

Import Growth |

Imports volume Change (in million US$) |

| 2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

| Textiles |

1985.7767 |

1936.2407 |

2060.4068 |

0.1240 |

-0.0250 |

0.0641 |

-49.536 |

124.1661 |

| Apparel |

38902.1906 |

40569.9907 |

35197.3464 |

0.1261 |

0.0429 |

-0.1324 |

1667.8 |

-5372.64 |

| Leather |

471.3925 |

506.4059 |

375.0113 |

0.1420 |

0.0743 |

-0.2595 |

35.0134 |

-131.395 |

| Fish |

77.9453 |

74.2316 |

43.4673 |

0.0472 |

-0.0477 |

-0.4144 |

-3.7137 |

-30.7643 |

| Other Manufacturing |

2623.2417 |

2843.7894 |

2539.8026 |

0.5595 |

0.0841 |

-0.1069 |

220.5477 |

-303.987 |

| Service |

5446.1340 |

6213.7460 |

6019.8250 |

0.2895 |

0.1409 |

-0.0312 |

767.612 |

-193.921 |

| Agri & Food |

852.9225 |

982.8277 |

952.5461 |

0.6289 |

0.1523 |

-0.0308 |

129.9052 |

-30.2816 |

Table 11.

Import performance of Bangladesh during Covid-19.

Table 11.

Import performance of Bangladesh during Covid-19.

| |

Import ( Million US$) |

Import Growth |

Imports volume Change (in million US$) |

| |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

| Textiles |

13490.7205 |

12624.28 |

10524.59 |

0.1836 |

-0.0642 |

-0.1663 |

-866.44 |

-2099.69 |

| Apparel |

230.2438 |

211.8589 |

213.2673 |

-0.1441 |

-0.0798 |

0.0066 |

-18.3849 |

1.4084 |

| Leather |

241.4981 |

218.8194 |

166.0384 |

-0.1150 |

-0.0939 |

-0.2412 |

-22.6787 |

-52.781 |

| Fish |

5.5063 |

7.219488 |

5.013472 |

0.605493347 |

0.3111 |

-0.3056 |

1.713188 |

-2.20602 |

| Other Manufacturing |

35369.5111 |

35899.87 |

29140.66 |

0.1354 |

0.0150 |

-0.1883 |

530.3589 |

-6759.21 |

| Service |

9619.1700 |

9557.7828 |

7926.6199 |

0.1319 |

-0.0064 |

-0.1707 |

-61.3872 |

-1631.16 |

| Agri & Food |

7016.8570 |

7594.109 |

8462.168 |

0.0762 |

0.0823 |

0.1143 |

577.252 |

868.059 |

The import performance data of Bangladesh also provide crucial insights. The fall in imports from the textile sector is supported by the results. Although CGE results suggest a decrease in apparel imports the actual data shows an increase in apparel imports by$1.40m. The imports of other manufacturing sectors drastically fall due to shocks caused by the pandemic and this high decrease is also suggested by the CGE analysis results. Service imports also substantially dropped during the pandemic and simulated results also suggest a high fall in imports in the service sector. The import data on Agri and food sectors drastically contradict the proposed simulated results. Although CGE simulated results suggest a substantial reduction in the Agri and food imports in Bangladesh due to shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic the actual data suggests a high increase in the import of Agri and Food sector in Bangladesh.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 epidemic has significantly damaged global supply chains. Significant setbacks have been experienced in the performance of the finances, lead times, customers, and manufacturing. The COVID-19 epidemic has brought attention to the weakness of the world's supply chains due to the lack of raw materials, the interruption of manufacturing and travel, and social alienation. COVID-19 is likely to have a big impact on trade and out of Bangladesh in different ways. The pandemic caused a problem that impacts both supply and demand, making it more challenging to effectively respond. The increased load of COVID-19 on Bangladesh inevitably shrinks the size of the industry, which lowers export supply. Exports will decline, particularly in fields and nations where working remotely is impractical. A commodity's domestic demand as well as production may be affected by the COVID-19 load. The pandemic had a significant impact on the Bangladeshi economy as numerous important economic indices were already in decline. This study attempts to identify the trade scenarios during the pandemic with descriptive data, the simulated trade scenario in different sectors under different level shocks caused by COVID-19 using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model. The study applies the GTAP 10 database and analyzes the effects of different levels of demand shock and trade disruptions caused by trade costs due to the Covid-19 pandemic on export, import, and output during the pandemic and compares them with the actual data. As proposed by the previous studies, this study assumed private consumption (as a proxy to demand shock) to be declined by 2%, 3.5%, and 5% under the low, medium, and high scenarios and trade costs (as a proxy to trade disruptions) rose by 1.5%, 2.5% and 5% in the low, medium, and high shock scenarios respectively.

The results of the study suggest that both demand shock and trade disruptions substantially affect the export, import, and domestic output of Bangladesh during the pandemic. The analysis results suggest that the higher level of shocks will have a higher impact on the export, import, and domestic output. The CGE model also analyses the combined effects of both shocks on the trade performance of Bangladesh. The analysis results indicate that the combined effects of both demand shock and trade disruptions are higher than their individual effects in all sectors in Bangladesh. The actual export and import data cross-validate the CGE analysis results and provide mixed findings on the trade performance of various sectors of Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study results provide crucial policy insights. The results depict that the demand and trade shocks caused by the Covid-19 pandemic substantially affect the export and import of Bangladesh. As Bangladesh is a highly export and import-oriented economy, proper steps should be taken to compensate for the impacts of the shocks on the trade and output of Bangladesh.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mohammad Monirul Islam; Methodology, Mohammad Monirul Islam; Validation, Farha Fatema and Tania Rahman; Formal analysis, Mohammad Monirul Islam; Resources, Farha Fatema; Writing – review & editing, Tania Rahman; Supervision, Farha Fatema and Tania Rahman; Project administration, Farha Fatema; Funding acquisition, Farha Fatema.

Funding

International Publication Grant and UGC research Grant 2020-21

References

- ADB. The economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on developing Asia. ADB BRIEFS, NO. 128. 2020.

- Ahamed, F. Macroeconomic Impact of Covid-19: A case study on Bangladesh. IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance (IOSR-JEF) 2021, 12, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Ali, M.J.; Bhuiyan, A.B.; Solaiman, M.; Rahman, M.A. The impact of covid-19 pandemic on the economic growth in Bangladesh: A conceptual review. American Economic & Social Review 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J. Note: Mayday, Mayday, Mayday! Responding to environmental shocks: Insights on global airlines’ responses to COVID-19. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2020, 143, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, R.; Tomiura, E. Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19. In Economics in the Time of COVID-19; Baldwin, R., di Mauro, B.W., Eds.; A VoxEU.org Book, Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, 2020; Available online: https://voxeu.org/system/files/epublication/COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Barichello, R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Anticipating its effects on Canada's agricultural trade. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie 2020, 68, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBS. In Bangladesh Statistics 2020; p. 2020.

- Chowdhury, M.; Sarkar, A.; Paul, S.K.; Moktadir, M. A case study on strategies to deal with the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in the food and beverage industry. Operations Management Research 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Paul, S.K.; Kaisar, S.; Moktadir, M.A. COVID-19 pandemic related supply chain studies: A systematic review. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2021, 148, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinakaran, D.D.P.; Kesavan, N. Exports and imports stagnation in India during COVID-19-A Review. GIS Business (ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-15-Issue-4-April-2020). 2020.

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenett, S.; Fiorini, M.; Fritz, J.; Hoekman, B.; Lukaszuk, P.; Rocha, N.; Shingal, A. Trade policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Evidence from a new data set. The World Economy 2022, 45, 342–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Azevedo, A.L. COVID-19: Outcomes for global supply chains. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society 2020, 15, 424–438. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszczynski, L. The COVID-19 pandemic and international trade: Temporary turbulence or paradigm shift? European Journal of Risk Regulation 2020, 11, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunessee, S.; Subramanian, N. Ambiguity and its coping mechanisms in supply chains lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic and natural disasters. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2020, 40, 1201–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, K.; Shahwali, D. Impact of COVID 19 on international trade and China’s trade. Turkish Economic Review 2020, 7, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, K.; Mukunoki, H. The impact of COVID-19 on international trade: Evidence from the first shock. Journal of The Japanese and International Economies 2021, 60, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMF. World economic outlook: The Great Lockdown; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Fatema, F. Do business strategies affect firms' survival during the COVID-19 pandemic? A global perspective. Management Decision 2023, 61, 861–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoso, I.; Ram, N.; Shah, A.A.; Shafiq, K.; Shaikh, F.M. Analysis of welfare effects of South Asia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) on Pakistan’s economy by using CGE model. Asian Social Science 2011, 7, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Nafi, S.M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on tourism: Perceptions from Bangladesh. Available at SSRN 3632798. 2020. 2020.

- Lewis, J.D.; Robinson, S.; Thierfelder, K. Free trade agreements and the SADC economies. Journal of African Economies 2003, 12, 156–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ornelas, E.; Shi, H. The Trade Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic. The World Economy 2021, 45, 3751–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, P.J.; Maclaren, D. Gains and losses from regional trading agreements: A survey. Economic Record 2004, 80, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, M.; Mattoo, A.; Van Der Mensbrugghe, D. The potential impact of COVID-19 on GDP and trade: A preliminary assessment. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper2020.

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P. A production recovery plan in manufacturing supply chains for a high-demand item during COVID-19. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2020, 51, 104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P.; Moktadir, M.A.; Lau, K.H. Supply chain recovery challenges in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research 2021, 136, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Zhang, J.X. The economic impacts of the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement-A general equilibrium analysis. China Economic Review 2018, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.H.; Razzaque, A.; Rahman, J.; Shadat, W.B. Socio-economic Impact Assessment of Covid-19 and Policy Implications for Bangladesh. bigd Policy Brief, Volume 1, SERIES: MACROECONOMICS 01, 01 SEPTEMBER 2020. 2020.

- Raihan, S. Covid-19 and the challenges of trade for Bangladesh; The Daily Star: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020; Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/covid-19-and-the-challenges-trade-bangladesh-1956405 (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Segal, S.; Gerstel, D. The global economic impacts of COVID-19; Center for Strategic and International Studies(CSIS): Washington, DC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriar, M.S.; Islam, K.; Zayed, N.M.; Hasan, K.; Raisa, T.S. The impact of COVID-19 on Bangladesh's economy: A focus on graduate employability. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 2021, 8, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, A.; Hoy, C.; Ortiz-Juarez, E. Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty. WIDER working paper. 2020.

- Verma, P.; Dumka, A.; Bhardwaj, A.; Ashok, A.; Kestwal, M.C.; Kumar, P. A statistical analysis of impact of COVID19 on the global economy and stock index returns. SN Computer Science 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, N.M.; Khan, S.; Shahi, S.K.; Afrin, M. Impact of coronavirus (covid-19) on the world economy, 2020: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Science 2021, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).