1. Introduction

Population aging is the most severe problem the world has ever experienced. In China, population aging is also progressing. China entered the “aging society” in 2000 and the “aged society” in 2022, and only just 22 years, the population aging problem has become significantly more severe. Population aging is likely to continue unabated in the foreseeable future. In China, rural areas are leading the way in anticipating this trend. In rural areas, in addition to the current aging population, due to the accelerated outflow of younger generations to urban areas, population aging has become even more severe. The problem of population aging has become a critical problem.

In rural areas, where the population aging is becoming more severe, the demand for medical and long-term care services is anticipated to rise. However, there is a lack of infrastructure specifically designed for the elderly, and social capital and living conditions lag are inferior to those in urban areas. Given this situation, it is assumed that many rural residents will migrate to urban areas after retiring. On the other hand, Rural areas are blessed with abundant natural resources. Rural residents are in a healthy state both physically and mentally, and they can lead a self-sufficient life in areas where agriculture thrives. Moreover, many residents choose to settle in rural areas due to strong connections with relatives and local communities built through social interactions, mutual assistance, and a sense of belonging and attachment to their hometown.

However, suppose many elderly rural residents migrate to urban areas. In that case, there may be an increase in demand for healthcare, welfare, and caregiving services which could significantly burden urban medical institutions, lifestyle support, and care facilities. On the contrary, rural areas may experience decreased demand for services such as health care and transportation due to migration to urban areas, resulting in situations where these services cannot be maintained and potentially threatening the sustainability of rural areas. Alternatively, if many elderly residents continue to reside in rural areas, providing appropriate support and developing infrastructure is necessary.

Therefore, understanding the intention of residents to migrate to urban areas after retirement (referred to hereafter as “post-retirement migration intention”) and the variables that affect the intention can provide necessary knowledge for estimating future rural-urban migration and for determining what social capital and environmental conditions are required in urban for residents migrate to urban areas, and in rural areas for those who continue to live in rural areas after retirement. Moreover, the findings gained from this study are expected to be beneficial not only for rural areas in China but also for countries around the world facing the challenges of population aging. However, there is a scarcity of quantitative research that specifically analyzes the post-retirement migration intention and its influencing variables among cultivators in rural areas.

In this study, we focus on the rural areas of Bayan Nur, Inner Mongolia, China, which have moderate economic conditions and where agriculture is the primary industry. We select three rural areas with different economic and living conditions and conduct an intention survey regarding whether rural residents (The rural residents primarily refer to the potential elderly people between the ages of 45–60 who are on the verge of entering the elderly age group.) intend to migrate to urban areas after retirement. Using the logistic regression model, we aim to understand which variables impact post-retirement migration intention and how each variable affects post-retirement migration intention. Additionally, by focusing on the differences in age and the proportion of mobile income, we aim to determine the variables that influence the residents’ intentions in each group and to clarify how age and the proportion of mobile income affect rural residents’ post-retirement migration intention. The structure of the paper is as follows. In section 2, we review the existing literature on migration intention.

Section 3 introduces the data and methods used in this study.

Section 4 analyzes the variables influencing the post-retirement migration intention of the potential elderly people in rural areas. In section 5, we summarize the study and present future research directions.

2. Literature Review

Secure living and good quality of life are expectations for human society’s survival and sustainable development at any time. Migration is one of the pathways to realizing these expectations [

1]. Migration is regarded as a positive force for reducing regional income disparities and fostering the development of rural areas. The assimilation and reorganization of rural labor by migrants influence local agricultural development and environmental changes [

2,

3]. The remittances generated by migration increase the purchasing power of households, promote agricultural investment, ensure the food security of households [

4], as well as reducing poverty and improving household livelihoods [

5], and have a positive impact on the sustainable development of the area of origin [

6,

7].

Multiple researchers have demonstrated a strong correlation between migration intention and actual migration [

8,

9,

10]. Migration intention serves as a good predictive indicator for actual migration. In cases where migration flow data is scarce or even absent, migration intention data can be used to estimate migration flows [

11,

12]. In recent years, many researchers have concentrated on studying migration intention [

13,

14,

15]. Migration encompasses international migration, primarily from low-income countries to high-income countries [

16], and internal migration, mainly from rural to urban areas [

17]. The existing literature has extensively analyzed the variables influencing international and internal migration intention.

Regarding international migration, personal variables such as age, marital status, and migration experience have been confirmed to influence migration intention [

10]. Additionally, individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to migrate [

18]. This is because those with higher education are more likely to adapt to the cultural differences brought about by migration and are more inclined to cross cultural boundaries than those with lower education [

19]. Social and economic variables such as income have a significant impact on the intention of international migration [

20]. The probability of migration increases considerably with increased personal income [

21], and occupation-related changes in the labor market also influence the intention to migrate [

22]. Migration decisions are not solely individual choices but are often influenced by other family members [

23]. Family variables are also potential influencers of migration intention [

24]. Social networks in migration destinations are the most important driving force for international migration intention, whereas the intimate social network in the country of origin decreases the probability of international migration intention [

25]. Other potential determinants of migration intention include satisfaction with current life [

26]. Life satisfaction negatively correlates with migration intention; individuals dissatisfied with their current living conditions are more inclined to migrate [

27], and those with higher life satisfaction tend to have lower migration intention [

10].

Moreover, an increasing number of rural residents choose to migrate to urban areas due to urbanization. Societal and economic variables such as employment opportunities, economic capacity, and income play pivotal roles in determining the migration of rural residents [

28,

29,

30]. Personal variables like gender, age, education level, and marital status influence migration intention [

31,

32,

33]. Similar to international migration, migration decisions are not made exclusively by individuals but are influenced by family members, making family variables influential on migration intention [

34]. Those with greater connections with family members remaining in their hometowns are less likely to choose migration [

35]. Social networks in their hometown may also influence migration intention, and strong connections with their neighbors may discourage rural residents from migrating to urban areas [

35,

36]. Preferences for specific areas can shape migration intention, and these preferences are often influenced by regional characteristics. The livability of urban areas influences migration intention positively [

37], while environmental pollution in urban areas has a negative impact on rural residents’ migration intention [

38,

39]. Pollution can reduce life and work satisfaction, negatively affecting on the desire to migrate to urban areas [

40]. Furthermore, individual preference for their hometown negatively correlates with their desire to migrate to urban areas [

41,

42,

43].

Age is an important variable for migration, as younger individuals are more likely to migrate [

44]. A substantial proportion of migrants are rural youths. Even though their values may change over time, it is essential to analyze their migration intention because they may become potential migrants as time growth [

45]. Existing research on rural youth and the variables influencing their migration intention is abundant [

46,

47]. Personal variables such as gender, marital status, and educational background play a significant role in determining the migration intention of youths [

16,

48,

49]. Migration intention is also influenced by socioeconomic variables such as employment opportunities and employment status [

16,

50]. In addition, family backgrounds, including parents’ occupation, migration experience, and educational level, are considered to influence youths’ migration intention [

51,

52]. Migration intention decreases where importance is placed on being with family [

53]. Social networks play an important role in the formulation of migration intention. The social networks of close companions in the hometown are positively correlated with the intentions to remain in the hometown [

54]. The Internet has progressively emerged in rural areas due to technological development, allowing rural youth to reconcile information gaps, reduce digital divides, and establish connections with other areas [

55]. The use of the internet has shown a positive impact on the formation of migration intention among rural youth [

56]. However, this influence could also be triggered by negative media coverage. The internet may reduce preference towards hometown, especially the desire to remain there [

57,

58]. Adams et al. (2016) [

59] revealed the primary variables for non-migration as high satisfaction levels and limited mobility potential. And this limited mobility potential is more likely to result from the attachment to rural areas. Rural attachment is a critical variable influencing migration intention [

60].

In previous studies, sufficient research has been conducted on the variables that influence international migration and internal migration intention, and many of these studies have focused on youth. The main variables influencing migration intention include personal variables such as age, education, and gender, socioeconomic variables such as income and occupational status, family variables, variables related to social networks in hometown, as well as variables related to regional preferences such as satisfaction with the current areas and interest in the destination. Nonetheless, as the aging society progresses, research on the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents who are soon to enter old age becomes crucial. Currently, there is a lack of research that specifically targets potential elderly people in rural areas and focuses on studying post-retirement migration intention and influencing variables.

This study focuses on the rural areas of Bayan Nur in Inner Mongolia, China, as the research area and targets potential elderly people living in rural areas. The study aims to investigate the variables influencing post-retirement migration intention from various aspects, including personal variables, socioeconomic variables, family variables, variables related to social networks in the hometown, and variables related to regional preferences. Age is significantly correlated with migration, and potential elderly individuals in different age groups may exhibit distinct characteristics, leading to variations in the variables influencing post-retirement migration intention. This study employs age as a control variable to analyze the variables that influence migration intention in different age groups and focus on the characteristic differences between age groups to investigate the variations in the variables. In addition to fixed income derived from agriculture, rural residents also have mobile income from part-time jobs, small-scale family livestock farming classified as mobile income due to its instability and smaller scale), temporary work, and other sources. The higher the proportion of mobile income, the higher the opportunities outside of agriculture, indicating less reliance on rural areas and fewer restrictions imposed by rural conditions. Rural residents from different mobile income groups may have different variables influencing their migration intention. Finally, this study employs the proportion of mobile income as a control variable to analyze the impact of variations in the proportion of mobile income on migration intention.

3. Research Objectives and Methods

3.1. Study Area

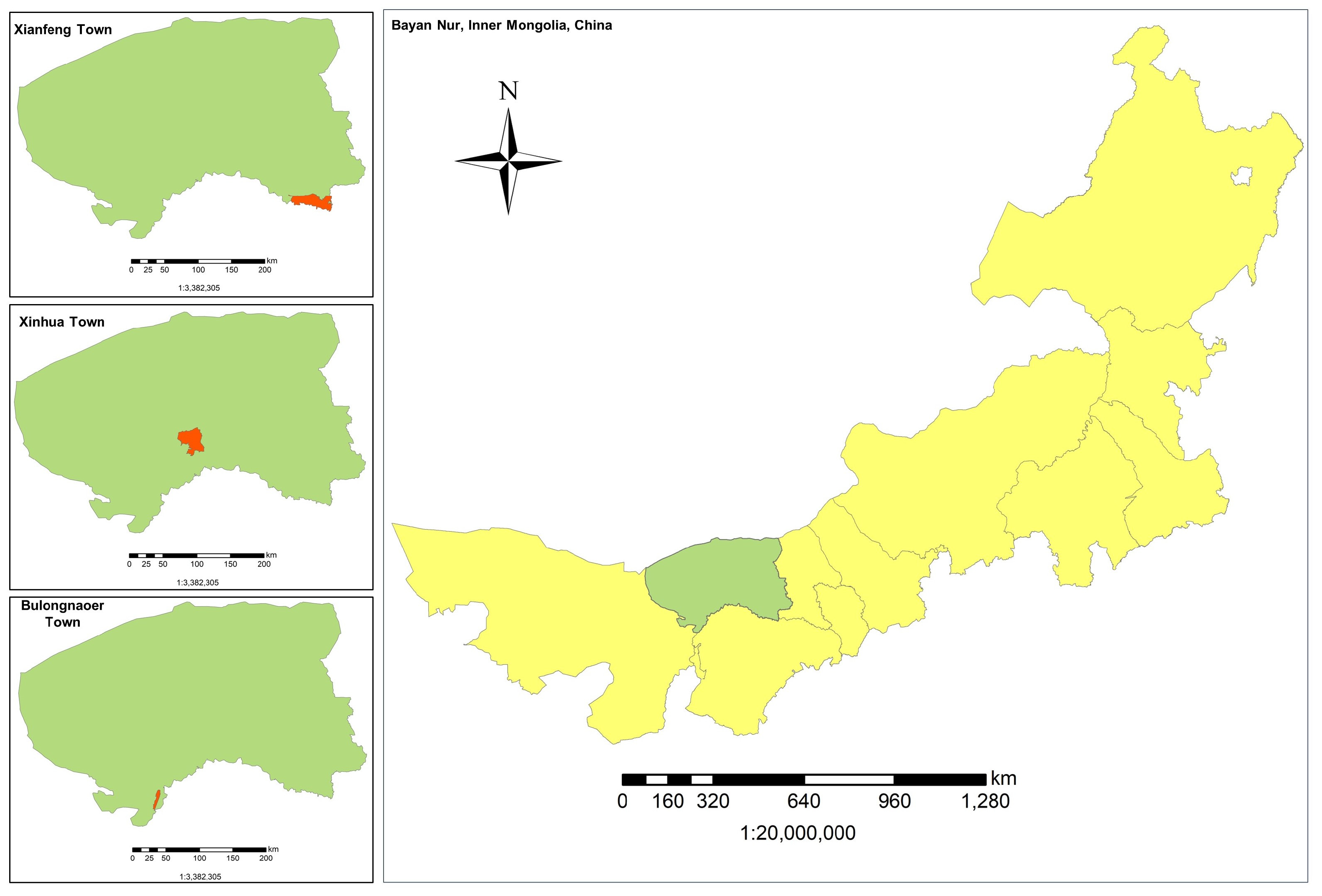

In order to make the research more generalizable, the following three survey areas were chosen for the field investigation, taking into consideration the accessibility of transportation and the differences in local economic level. The survey areas include Xianfeng Town, Xinhua Town, and Bulongnaoer Town, located in Bayan Nur in western Inner Mongolia (See

Figure 1). Among these, Xianfeng Town is in the eastern portion of Bayan Nur’s Urad South County. It borders Baotou on the east, Ordos on the south, Wulashan Town on the west, and is intersected by the Jingzang Expressway and National Highway 110 to the north, covering a total area of 488 km

2. Notably, Xianfeng Town has a thriving goji berry cultivation industry, resulting in relatively higher incomes for rural residents and a prosperous rural area. Xinhua Town is in the northern part of Linhe District, the central district of Bayan Nur. Compared to the other survey areas, it is closer to the city center and is known for cultivating vegetables. It covers a total area of 167.43 km

2. Bulongnaoer Town (referred to as Bulong Town) is situated in the southwest of Dengkou County, Bayan Nur. It is adjacent to the desert and covers a total area of 70.7 km

2. Xianfeng Town has the most favorable economic and living conditions among the three survey areas. In contrast, Xinhua Town has moderate economic and living conditions, while Bulongnaoer Town has relatively low economic and living conditions. In recent years, all three areas have experienced a decrease in the agricultural population, and most farmers are in the 45-60 age group.

3.2. Data

In this study, we examine the primary variables influencing post-retirement migration intention rather than examining actual rural residents who have already decided to migrate. The post-retirement migration intention can partially reflect their preferences for future retirement areas. Nonetheless, it is regrettable that there is a lack of official data regarding post-retirement migration intention, which is extremely relevant to our research. In order to acquire more authentic and reliable information, our data is mainly obtained through field investigations conducted via face-to-face interviews. The data collection was conducted in August 2011 for one month. As the author Zhou of this paper was born in Bayan Nur and had been researching rural areas in Bayan Nur for many years, it facilitated smooth face-to-face interviews with the surveyed residents.

In the study areas, respondents were randomly selected based on the following criteria. (1)45–60 years old. (2) willing to respond to the questionnaire. A total of 164 householders(In their absence, interviews were conducted with the spouse who fulfills the above criteria)were interviewed, including 54 from Xianfeng Town, 56 from Xinhua Town, and 54 from Bulongnaoer Town. Before conducting the interviews, they were informed that they would receive no monetary compensation and that their privacy would not be compromised. All interview and survey information were collected for research purposes only. The survey was conducted with the respondents’ verbal consent and cooperation.

In addition to the desired post-retirement living area as an indicator of rural residents’ post-retirement migration intention, there are several variables believed to influence post-retirement migration intention. These variables include gender, health status (individual variables), part-time employment, savings level (socio-economic variables), children’s residence and occupational stability (family variables), the number of companions in rural areas, and relationships with others in rural areas (variables related to rural social networks), evaluation of rural living, interest in urban living (variables related to preference for urban or rural areas). These associated variables were surveyed using specific question items, shown in

Table 1. The interviewees’ responses to these question items were self-evaluations.

3.3. Statistical Description of the Data and Research Method

Table 2 presents the statistical description of the sample population, which consists of 164 surveyed residents. The respondents were separated according to whether they intended to remain in rural areas or migrate to urban. From the statistical description of population characteristics, those who intend to migrate to urban areas are more likely to be male, to have a higher level of savings; and to have part-time employment experience. Rural residents with children in stable urban employment are more likely to migrate to the urban area. Moreover, those more interested in urban areas are more likely to migrate. On the other hand, residents who remain in rural areas can rely more on their friends, and the social networks they built within the rural community. Consequently, residents with more rural companions, who have established high-quality and intimate relationships with other rural residents, are more likely to remain in rural areas. In addition, those who intend to remain in rural areas tend to have a relatively positive evaluation of rural living.

This study employs the logistic regression model to objectively analyze the variables affecting migration intention to reveal the relationship between post-retirement migration intention and the potential influencing variables. The logistic regression equations are shown as Equation (1) and Equation (2).

Where: The objective variable y is a binary variable with the value 1 when the resident intends to migrate to urban areas after post-retirement and 0 when the resident intends to continue living in rural areas. X represents the vector of explanatory variables that influence the migration intention of rural residents. Specifically, x1-x9 represent the variables of gender, health status, part-time employment, savings level, children’s residence and occupation stability, the number of companions in rural areas, relationships with others in rural areas, evaluation of rural living, and interest in urban living. α0~α9 are parameters.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Variables Influencing Post-retirement Migration Intention

Using the collected data from 164 respondents, we analyze the main variables affecting rural residents’ post-retirement migration intention through the logistic regression model.

Table 3 shows the results using logistic regression models. Model 1 examined the impact of individual, socio-economic, and family variables and those variables related to rural social networks on rural residents’ migration intention. Model 2 incorporated variables related to the preference for the area, specifically the evaluation of rural living and interest in urban living, to examine the effect on migration intention. The Pseudo R-square values for model 1 and model 2 are 0.303, 0.479, and the AIC values are 173.090 and 137.37, respectively. R Whether from the Pseudo R-square or AIC values, it is evident that Model 2 is preferable to Model 1. Consequently, the conclusions derived from Model 2 are utilized in this study. Furthermore, A multicollinearity analysis was conducted to assess multicollinearity among the model’s influencing variables, and

Table 3 presents the maximal VIF value. All VIF values for influencing variables were less than 10.

Model 2 confirmed that gender, part-time employment, savings level, and children’s residence and occupation stability influence the migration intention, which have a positive effect on the intention to migrate to urban areas after post-retirement, whereas the number of companions in rural areas and the relationships with others in rural areas have a negative effect on the migration intention. Those who are male, have part-time employment experience, have a relatively high level of savings, have children with stable jobs in urban areas, have few companions in rural areas, and have weak relationships with others in rural areas are more likely to migrate to urban areas. In contrast, they are more willing to continue living in rural areas. Model 2 also revealed that the evaluation of rural living and interest in urban living influence migration intention. The evaluation of rural living has a negative effect on migration intention, whereas their interest in urban living has a positive effect. The greater their interest in urban living and the lower their evaluation of rural living, the more likely they are to migrate. Further examination of these variables is conducted in the following analysis.

Gender: Males who actively engage in agricultural work and social activities have more opportunities for social engagement and connections with urban areas than females who predominantly perform housework. Therefore, males are more likely to migrate to urban areas. On the other hand, females tend to avoid risks, which may explain why they prefer to remain in rural areas.

Part-time employment: Rural residents with part-time employment in other industries tend to have more connections with urban areas than those solely engaged in agriculture. As a result, these people with part-time employment are more likely to leave rural areas and have a stronger intention to migrate to urban areas.

Savings level: The expense of living in urban areas is greater than in rural areas. Therefore, it is challenging for rural residents without sufficient savings to migrate to the urban area. Those with no savings can only continue to live in rural areas due to financial constraints.

Children’s residence and occupation: If the children of rural residents work in urban areas and have stable employment, it is reasonable to assume that the rural residents would prefer to migrate to the urban and live near their children, which would provide a more secure and comfortable retirement.

The number of companions in rural areas and relationships with others in the rural area: The companions in rural areas are frequently closer and more amiable with each other than with their relatives, and they become reliable sources of daily support. Therefore, residents with a greater number of companions within the rural area are more likely to continue residing in rural areas after retirement. If the relationship with others in the rural area is positive, there is a tendency to remain in the rural area. Conversely, if negative, there is a tendency to migrate to the urban area.

Evaluation of rural living and interest in urban living: Rural residents who appreciate rural living are more likely to continue to reside in rural areas. Those with a significant interest in urban living are more likely to intend to migrate to urban after retirement. Individuals with little or no interest in urban living are more committed to remaining in rural areas.

4.2. Impact of Age Group on Post-retirement Migration Intention

Different age groups may have distinctive characteristics that influence their post-retirement migration intention. In order to investigate this, this section focuses on the differences between age groups and analyzes the variables that influence post-retirement migration intention at various age groups. The potential elderly people (45–60 years old) are divided into three age groups: the early potential elderly (45–49 years old), the middle potential elderly (50–54 years old), and the late potential elderly (55–60 years old). The number of people in each group (the proportion of people willing to migrate to urban areas) is 58 (47%), 59 (54%), and 47 (30%), respectively.

Using the above data, the logistic regression model is used to analyze the variables influencing post-retirement migration intention at various age groups. The results are shown in

Table 4. In

Table 4, Models 3, 4, and 5 investigate the variables that influence the post-retirement migration intention of individuals in the early potential elderly, the middle potential elderly and the late potential elderly. The range of Pseudo R-square values for the models is 0.53–0.63, and the AIC values are 50.295, 50.784, and 46.793, respectively. All variables’ VIF values are less than 10.

From

Table 4, it is evident that for rural residents in the early potential elderly, variables such as gender, savings level, the number of companions in rural areas, evaluation of rural living, and interest in urban living impact their post-retirement migration intention. Post-retirement migration intention of rural residents in the middle potential elderly are influenced by variables such as savings level, children’s residence and occupation stability, and relationships with others in rural areas. For rural residents in the late potential elderly, post-retirement migration intention is influenced by savings level, the number of companions in rural areas, evaluation of current rural living, and interest in urban living. These variables have the same signs as shown in

Table 3.

From the above, it can be observed that regardless of the age group of rural residents, the savings level is an important variable affecting their post-retirement immigration intention. However, besides the savings level, there are age-related differences in the variables that influence the post-retirement migration intention. These differences can be attributed to the disparities in characteristics between age groups. The following analysis further examines this aspect.

Gender: Those in the early potential elderly have superior physical health and fitness than those in the middle and late potential elderly, and tend to possess a more adventurous temperament, making them more capable of engaging in agricultural work and social activities. These contribute to the greater influence of gender on the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents in the early potential elderly.

Part-time employment: Compared to rural residents in the early and middle potential elderly, rural residents in the late potential elderly have spent more time within their rural social circles, relying more on these networks. Part-time employment might increase their connection to urban areas, decrease their dependence on rural social circles, and make them more inclined to migrate to urban areas. Hence, the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents in the late potential elderly are influenced by part-time employment.

Children’s residence and occupation stability: As mentioned above, rural residents in the early potential elderly have superior physical health and fitness, allowing them to prefer living independently rather than rely on their children. On the other hand, rural residents in the late potential elderly have developed a sense of autonomy and independence after adapting to the situation of their children leaving the household. They are more likely to maintain their independence and self-sufficiency than to rely on their children for support in their retirement. However, rural residents in the middle potential elderly maintain strong emotional connections with their children. In retirement, they expect to maintain a close relationship with their children and rely on their children’s support and care to meet their emotional and daily requirements. As a result, the variables of children’s residence and occupation stability only affect the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents in the middle potential elderly.

The number of companions in rural areas and relationships with others in rural areas: Rural residents in the early potential elderly are still in the career development phase. They need to establish a wide social network to expand their social circle, di-versify their connections, and seize opportunities. In contrast, rural residents in the late potential elderly may experience increased loneliness due to changes in their family dynamics, such as the departure of their children. As a result, they are more likely to seek out rural companions to establish relationships and alleviate loneliness. As for rural residents in the middle potential elderly, they typically must assume parental care responsibilities and deal with work-related pressures. Due to energy and time limitations, they are more likely to establish high-quality and stable intimate relationships to satisfy their emotional requirements. Therefore, rural residents in the early and late potential elderly prioritize the number of rural companions, while those in the middle potential elderly prioritize the quality of their relationships with others in rural areas.

Evaluation of rural living and interest in urban living: The early potential elderly is frequently in the career development stage and place greater emphasis on urban opportunities and growth potential. The late potential elderly may begin to face retirement problems, and compared to rural areas, urban areas may offer greater retirement convenience. On the other hand, the middle potential elderly has stable careers and act as family supporters, making it difficult for them to give up their current stable rural occupations and lifestyle even if they are interested in urban living or dissatisfied with rural living. Thus, variables such as interest in urban living and evaluation of rural living can influence the migration intention of rural residents in the early and late potential elderly but do not affect rural residents in the middle potential elderly.

4.3. Impact of the Proportion of Mobile Income on Post-retirement Migration Intention

This section examines the impact of the proportion of mobile income on migration intention after retirement. We investigate the variables that influence the post-retirement migration intention of various groups with varying levels of mobile income. The average proportion of mobile income, in addition to the fixed income from agriculture, is 28%, according to the survey data. Based on this indicator, the 164-sample data are divided into two groups: the low mobile income group (proportion of mobile income less than 28%) and the high mobile income group (proportion of mobile income above 28%). The number of rural residents in each group (the proportion of people willing to migrate to urban areas) is 91 (46%) and 73 (42%), respectively. Using this data, the logistic regression model is applied to investigate the variables influencing the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents in various mobile income groups. The analysis results are presented in

Table 5.

In

Table 5, Model 6 examines the variables influencing the migration intention of rural residents with low mobile income, while Model 7 examines the variables influencing the migration intention of rural residents with high mobile income. The Pseudo R-square values (AIC) for each model are 0.399 (95.464) and 0.665 (53.310), respectively. All the variables’ VIF values are below 10. Based on the results in

Table 5, we can analyze that for rural residents with low mobile income, gender, savings level, children’s residence and occupation stability, the number of companions in the rural area, relationships with others in rural areas, evaluation of rural living, interest in urban living, have an impact on their migration intention. On the other hand, for rural residents with high mobile income, variables such as savings level, the number of companions in rural areas, evaluation of rural living, and interest in urban living influence their post-retirement migration intention. These influential variables show the same signs as shown in

Table 3.

Regardless of whether rural residents belong to the group with low mobile income or the group with high mobile income, savings level, the number of companions in the rural area, evaluation of rural living, and interest in urban living influence their post-retirement migration intention. However, compared to the group with high mobile income, the migration intention of rural residents with low mobile income are influenced by gender, children’s residence and occupation stability, and relationships with others in rural areas. There are distinctions in the variables influencing the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents belonging to various mobile income groups. These differences are most likely attributable to the unique characteristics of the various mobile income groups. This is investigated further in the subsequent analysis.

Gender: In the group with low mobile income group, females are more likely to assume primary household and caregiving responsibilities, limiting their opportunities for social engagement. In contrast, in the group with high mobile income, females often have the chance to balance career and family responsibilities, possess better economic foundations, and enjoy equal access to social engagement as males. As a result, gender has no impact on residents’ migration intention in the high mobile income group, whereas it does influence rural residents in the low mobile income group.

Children’s residence and occupation stability: Rural residents with high mobile income earn income from agriculture and other part-time employment outside of agriculture. They can rely on themselves for retirement without depending on their children. On the other hand, rural residents in the low mobile income group depend primarily on agriculture, making it more difficult to save enough for retirement. The difficulty in obtaining retirement money could make the low mobile income group more inclined to rely on their children for retirement. Hence, children’s residence and occupation stability become an important variable influencing the post-retirement migration intention of rural residents with low mobile income, whereas it has no effect on the migration intention of rural residents with high mobile income.

Relationships with others in rural areas: Compared to rural residents with low mobile income, rural residents with high mobile income have higher income, more economic resources, and the ability to establish broader social networks and relationships with more people from other areas and urban areas, enabling them to rely on themselves for retirement and receive support from people from other areas and urban areas. In contrast, rural residents with low mobile income, constrained by their own income, resources and limited social networks, rely more on the support of other rural residents. The relationships with others in rural areas are crucial in determining whether they can access support, resources. Thus, the migration intention of rural residents with low mobile income are influenced by relationships with others in rural areas, whereas the migration intention of rural residents with high mobile income are not affected by relationships with others in rural areas.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to provide references and actionable suggestions for optimizing the future development of an aging society and contributing to sustainable social development. The investigation targeted potential elderly people (45–60 years old) residing in rural areas of western China. This study used survey data and the logistic regression model to investigate the variables that influence post-retirement migration intention. Then the study divided all rural residents into three different age groups: the early potential elderly, the middle potential elderly, and the late potential elderly. The analysis investigated the variables that influence migration intention of rural residents in various age groups. Lastly, the study divided rural residents into two groups based on the proportion of mobile income: the group with low mobile income and the group with high mobile income. It examined the variables that influence the migration intention of rural residents in these various mobile income groups.

Based on the analysis in this study, it can be concluded that gender, part-time employment, savings level, children’s residence and occupation stability, the number of companions in rural areas, relationships with others in rural areas, evaluation of rural living, and interest for urban living all influence post-retirement migration intention. Specifically, gender, part-time employment, savings level, children’s residence and occupation stability, and interest in urban living positively affect migration intention, whereas the number of rural companions, relationships with others in rural areas, and evaluation of rural living have a negative effect. Considering the impact of age differences on post-retirement migration intention, rural residents of all age groups are significantly influenced by their level of savings. However, besides the level of savings, the variables influencing the post-retirement migration intention vary across age groups, and this variation can be attributed to the differences between age groups’ characteristics. Finally, considering the impact of the characteristic differences in the proportion of mobile income on migration intention, it can be concluded that both low and high mobile income groups are influenced by the number of companions in rural areas, savings level, evaluation of rural living, and interest in urban living in their migration intention. Compared to the group with high mobile income, the migration intention of rural residents with low mobile income are also influenced by gender, children’s residence and occupation stability, and relationships with others in rural areas. These differences are most likely attributable to the unique characteristics of the various mobile income groups.

This study employed age and the proportion of mobile income as control variables and examined their individual effects on post-retirement migration intention. However, due to the limited data, the interaction effects of age and the proportion of mobile income on migration intention are not accounted for in this study. Future research will collect more data to examine the interaction effects between age and the proportion of mobile income on migration intention. In addition, this study only analyzed the variables influencing the migration intention of residents in three rural areas of Bayan Nur, Inner Mongolia, China. Future research will evaluate the generalizability of the conclusions obtained in this study by incorporating more rural areas.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, X.Z. and W.F.; methodology, X.Z..; investigation, X.Z.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and W.F.; supervision, X.Z. and W.F.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by Institute of Transportation, Inner Mongolia University, Grant Number DC1900000198.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Mckenzie, D. J. A Profile of the World’s Young Developing Country Migrants. Popul Dev Rev 2008, 34, 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, L. C.; Peluso, N. L.; Carlson, K. M.; Afiff, S. Circular Labor Migration and Land-Livelihood Dynamics in Southeast Asia’s Concession Landscapes. Journal of Rural Studies 2020, 73, 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Robson, J. P.; Klooster, D. J. Migration and a New Landscape of Forest Use and Conservation. Environ Conserv 2019, 46, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Choithani, C. Understanding the Linkages between Migration and Household Food Security in India. Geographical Research 2017, 55, 192–205. [CrossRef]

- Sunam, R.; Barney, K.; McCarthy, J. F. Transnational Labour Migration and Livelihoods in Rural Asia: Tracing Patterns of Agrarian and Forest Change. Geoforum 2021, 118, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. N.; Boyd, E.; Fábos, A.; Fransen, S.; Jolivet, D.; Neville, G.; de Campos, R. S.; Vijge, M. J. Migration Transforms the Conditions for the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet Planetary Health 2019, 3, e440–e442. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. Wan Laki Aelan? Diverse Development Strategies on Aniwa, Vanuatu. Asia Pac Viewp 2013, 54, 246–263. [CrossRef]

- van Dalen, H. P.; Henkens, K. Explaining Emigration intention and Behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005-10. Popul Stud 2013, 67, 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Creighton, M. J. The Role of Aspirations in Domestic and International Migration. Social Science Journal 2013, 50, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Docquier, F.; Peri, G.; Ruyssen, I. The Cross-Country Determinants of Potential and Actual Migration. International Migration Review 2014, 48, S37–S99. [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, J.; Auer, D.; Laczko, F. Linking Migration intention with Flows: Evidence and Potential Use. International Migration 2019, 57, 36–57. [CrossRef]

- Laczko, F.; Tjaden, J.; Auer, D. Measuring Global Migration Potential, 2010–2015. International Organisation for Migration. Global Migration Data Analysis Centre: Data Briefing Series 2017, 9, 1–14.

- Carling, J.; Schewel, K. Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration. J Ethn Migr Stud 2018, 44, 945–963. [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, C.; Paparusso, A. Remain or Return Home: The Migration intention of First-Generation Migrants in Italy. Popul Space Place 2019, 25, e2174. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R. Migration Aspirations among Youth in the Middle East and North Africa Region. J Geogr Syst 2019, 21, 487–507. [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, A.; Goujon, A.; Jiang, L. The Migration intention of Young Egyptians. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9803. [CrossRef]

- Kirdar, M. G.; Saracoǧlu, D. Ş. Migration and Regional Convergence: An Empirical Investigation for Turkey. Papers in Regional Science 2008, 87, 545–566. [CrossRef]

- Dao, T. H.; Docquier, F.; Parsons, C.; Peri, G. Migration and Development: Dissecting the Anatomy of the Mobility Transition. J Dev Econ 2018, 132, 88–101. [CrossRef]

- Bauernschuster, S.; Falck, O.; Heblich, S.; Suedekum, J.; Lameli, A. Why Are Educated and Risk-Loving Persons More Mobile across Regions? J Econ Behav Organ 2014, 98, 56–69. [CrossRef]

- Baláž, V.; Williams, A. M.; Fifeková, E. Migration Decision Making as Complex Choice: Eliciting Decision Weights Under Conditions of Imperfect and Complex Information Through Experimental Methods. Popul Space Place 2016, 22, 36–53. [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C.; Okatenko, A. Out-Migration, Wealth Constraints, and the Quality of Local Amenities. J Dev Econ 2014, 110, 52–63. [CrossRef]

- Bijwaard, G. E.; Wang, Q. Return Migration of Foreign Students. European Journal of Population 2016, 32, 31–54. [CrossRef]

- Nauck, B.; Settles, B. H. Immigrant and Ethnic Minority Families: An Introduction. Source: Journal of Comparative Family Studies 2001, 32, 461–463. [CrossRef]

- Ruyssen, I.; Salomone, S. Female Migration: A Way out of Discrimination? J Dev Econ 2018, 130, 224–241. [CrossRef]

- Manchin, M.; Orazbayev, S. Social Networks and the Intention to Migrate. World Dev 2018, 109, 360–374. [CrossRef]

- Chindarkar, N. Is Subjective Well-Being of Concern to Potential Migrants from Latin America? Soc Indic Res 2014, 115, 159–182. [CrossRef]

- Otrachshenko, V.; Popova, O. Life (Dis)Satisfaction and the Intention to Migrate: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Socio-Economics 2014, 48, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W. Economic Incentives and Settlement Intentions of Rural Migrants: Evidence from China. J Urban Aff 2019, 41, 372–389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y. Administrative Level, City Tier, and Air Quality: Contextual Determinants of Hukou Conversion for Migrants in China. Computational Urban Science 2021, 1, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, J. Settlement Intention of Migrants in Urban China: The Effects of Labor-Market Performance, Employment Status, and Social Integration. Applied Geography 2022, 147, 102773. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, X.; Yan, J.; Xin, L.; Sun, L. Length of Stay in Urban Areas of Circular Migrants from the Mountainous Areas in China. J Mt Sci 2016, 13, 947–956. [CrossRef]

- Czaika, M. Are Unequal Societies More Migratory? Comp Migr Stud 2013, 1, 97–122. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, W.; Song, X. Influence Factor Analysis of Migrants’ Settlement Intention: Considering the Characteristic of City. Applied Geography 2018, 96, 130–140. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhong, H. A Demographic Factor as a Determinant of Migration: What Is the Effect of Sibship Size on Migration Decisions? J Demogr Economics 2019, 85, 321–345. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, B. Environmental Non-Migration: Analysis of Drivers, Factors, and Their Significance. World Dev Perspect 2023, 29, 100475. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, Y. Road to the City: Impact of Land Expropriation on Farmers’ Urban Settlement Intention in China. Land use policy 2022, 123, 106432. [CrossRef]

- He, S. Y.; Chen, X.; Es, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, K. K.; Lin, Z. Liveability and Migration Intention in Chinese Resource-Based Economies: Findings from Seven Cities with Potential for Population Shrinkage. Cities 2022, 131, 103961. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, M.; Liao, L.; Li, W. The Effect of Air Pollution on Migrants’ Permanent Settlement Intention: Evidence from China. J Clean Prod 2022, 373, 133832. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, F. City-Level Socioeconomic Divergence, Air Pollution Differentials and Internal Migration in China: Migrants vs Talent Migrants. Cities 2023, 133, 104116. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, D. Air Pollution’s Impact on the Settlement Intention of Domestic Migrants: Evidence from China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2022, 95, 106761. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Hometown Landholdings and Rural Migrants’ Integration Intention: The Case of Urban China. Land use policy 2022, 121, 106307. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich-Schad, J. D.; Henly, M.; Safford, T. G. The Role of Community Assessments, Place, and the Great Recession in the Migration intention of Rural Americans. Rural Sociol 2013, 78, 371–398. [CrossRef]

- Thissen, F.; Fortuijn, J. D.; Strijker, D.; Haartsen, T. Migration intention of Rural Youth in the Westhoek, Flanders, Belgium and the Veenkoloniën, The Netherlands. J Rural Stud 2010, 26, 428–436. [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Jarreau, J. Determinants of Emigration: Evidence from Egypt. Economic Research Forum (ERF)–Egypt 2016.

- Becerra, D. The Impact of Anti-Immigration Policies and Perceived Discrimination in the United States on Migration intention among Mexican Adolescents. International Migration 2012, 50, 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H. D.; Gram, M. ‘The Brainy Ones Are Leaving’: The Subtlety of (Un)Cool Places through the Eyes of Rural Youth. J Youth Stud 2018, 21, 620–635. [CrossRef]

- Rérat, P. The Selective Migration of Young Graduates: Which of Them Return to Their Rural Home Region and Which Do Not? J Rural Stud 2014, 35, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- García-Arias, M. A.; Tolón-Becerra, A.; Lastra-Bravo, X.; Torres-Parejo, Ú. The Out-Migration of Young People from a Region of the “Empty Spain”: Between a Constant Slump Cycle and a Pending Innovation Spiral. J Rural Stud 2021, 87, 314–326. [CrossRef]

- Van Mol, C. Migration Aspirations of European Youth in Times of Crisis. J Youth Stud 2016, 19, 1303–1320. [CrossRef]

- Taima, M.; Asami, Y. Determinants and Policies of Native Metropolitan Young Workers’ Migration toward Non-Metropolitan Areas in Japan. Cities 2020, 102, 102733. [CrossRef]

- Plopeanu, A. P.; Homocianu, D.; Florea, N.; Ghiuta, O. A.; Airinei, D. Comparative Patterns of Migration intention: Evidence from Eastern European Students in Economics from Romania and Republic of Moldova. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4935. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D. “I Wouldn’t Stay Here”: Economic Crisis and Youth Mobility in Ireland. International Migration 2014, 52, 236–249. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. M.; Jephcote, C.; Janta, H.; Li, G. The Migration intention of Young Adults in Europe: A Comparative, Multilevel Analysis. Popul Space Place 2018, 24, e2123. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Grünwald, L.; Hirte, G. The Effect of Social Networks and Norms on the Inter-Regional Migration intention of Knowledge-Workers: The Case of Saxony, Germany. Cities 2016, 55, 61–69. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, A. R. R. T.; Onitsuka, K.; Sianipar, C. P. M.; Basu, M.; Hoshino, S. To Migrate or Not to Migrate: Internet Use and Migration Intention among Rural Youth in Developing Countries (Case of Malang, Indonesia). Digital Geography and Society 2023, 4,100052. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, T. J.; Shuttleworth, I. The Effects of Information and Communication Technologies on Residential Mobility and Migration. Popul Space Place 2018, 24, e2111. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F. Navigating Aspirations and Expectations: Adolescents’ Considerations of Outmigration from Rural Eastern Germany. J Ethn Migr Stud 2018, 44, 1032–1049. [CrossRef]

- Priatama, R. A.; Onitsuka, K.; Rustiadi, E.; Hoshino, S. Social Interaction of Indonesian Rural Youths in the Internet Age. Sustainability 2020, 12, 115. [CrossRef]

- Adams, H. Why Populations Persist: Mobility, Place Attachment and Climate Change. Popul Environ 2016, 37, 429–448. [CrossRef]

- Theodori, A. E.; Theodori, G. E. Perceptions of Community and Place and the Migration intention of At-Risk Youth in Rural Areas. J Rural Soc Sci 2014, 29, 5. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol29/iss1/5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).