According to the Neumann–Kopp law, the heat capacity of a solid compound

AwB1–w is expressed as the sum of the weighted heat capacities of the compound elements: C = C

A⋅

w + C

B⋅(1 –

w), where

w is the mass fraction of element

A. This law is valid only in limited ranges of temperatures and values of

w for each solid compound, for example [

1]. It would be interesting to find out if it is possible to express any other physical observable for an arbitrary solid compound in the same way? It does not matter what kind of solid compound we take - a chemical compound, a mechanical mixture, an alloy or ceramics, first of all we want to consider the possibility of writing an arbitrary physical quantity in terms of an atomic or molar weighted sum of the physical quantities of the elements of the compound. In presiding work we considered mechanical properties of metal alloys under irradiation [

2], and found that such description is possible in different intervals of radiation doses for different alloys. We also found that the thermophysical properties of various nuclear materials can also be expressed in terms of weighted sums of the thermophysical properties of the elements of materials [

3,

4,

5]. In all of these results, weighted sums were multiplied by constants constructed from the atomic numbers of all the elements of a particular compound, chemical indices, or mass fraction values, and all of these constants did not equal one. Having a large set of such data for various materials, we can predict a new material with desired properties, which is currently done, in most cases, only thanks to the intuition of the experimenter. In this work, we continued to collect data, now on the magnetic characteristics of various materials.

Let us first consider the USb–

x(ThSb) mixture, whose magnetic transition temperatures as a function of

x are shown in

Figure 1. All elements of this mixture are paramagnetic in all temperature ranges. Thorium is a temperature independent paramagnetic [

6]. The mixture is either a ferromagnetic or an antiferromagnetic, depending on

x. At first glance, it is impossible to apply the idea of representing the magnetic transition temperature of a mixture as a weighted sum of mole fractions of the magnetic transition temperatures of its elements. But we know that uranium exhibits a rapid increase in the crystallographic cell at

TU = 43 K [

7], which coincides with a slight change in the magnetic susceptibility of

U at approximately the same temperature [

6]. Antimony has a magnetic susceptibility that does not depend on temperature down to

TSb = 4 K, and below this temperature the magnetic susceptibility depends on temperature [

8]. Thus, we can write the next formula for the temperature of magnetic transition of U

1-xTh

xSb:

where

q is some constant and

TTh = 0 K.

Table 1 shows the experimental values of

and those calculated by (1.1) with adjusted

q.

Table 1 shows that at

q = 5.34 and

x ∈ [0.36, 0.55], formula (1.1) works very well with relative errors between the experimental and calculated temperatures of less than 1%.

Is the result obtained is accidental with a constant q in some range of x values? If we have such accidental coincidences for a large set of different materials and physical observables, then we can assume that this is a manifestation of some general physical law.

Let us consider magnetic the Laves phase compound Er(Fe

0.8–xMn

0.2–yCo

x+y)

2, which has ferromagnetic properties at certain

x and

y (

Table 2) [

9]. Manganese changes the Curie temperature of the compound, even though

Mn is not a ferromagnetic. We will make calculation with and without Néel temperature

TN of

Mn:

Where the Curie temperatures:

= 18.74 K [

10],

= 1044 K [

11],

= 1390 K [

12],

= 100 K [

13] or 0 K.

Table 2 shows that at

q = 0.27 formula (1.2) describes the Curie temperatures of the compound Er(Fe

0.8–xMn

0.2–yCo

x+y)

2 at

x = 0.1,

y = 0 and

y = 0.1 with a relative error less than 1% without taking into account the magnetic temperature of

Mn. The inclusion of the Néel temperature of

Mn in the calculation worsens the relative error to 2.2%. It seems that we need to take

TC of all elements, while the characteristics of

Mn are inside

q. Is this result also a mere coincidence?

The fundamental question is, what is the nature of the variable q, which in some ranges of values of x becomes a constant? The electronic structure of a solid is determined by the atomic numbers (nuclear charges) of the elements of the solid, so you can write: q = q(atomic numbers). For different x, the lattice parameters of a crystalline solid change, which leads to a change in the physical observables that characterize the properties of the solid. So we can write: q = q(atomic numbers, x, lattice parameters). Considering the ceramics (Ni1–xZnx)Fe2O4 as an example, we now consider the structure of q.

This ceramics (Ni

1–xZn

x)Fe

2O

4 is a substitutional solid solution [

14]. With a change in the content of

Zn, which replaces

Ni atoms, the Curie temperature of this ceramics changes (

Table 3). The structure of the parameter

q in (1.3′) is shown as follows:

where

= 630 K [

15],

= 1044 K [

11], atomic numbers:

Ni = 28,

Zn = 30,

Fe = 26,

O = 8. The form

q is chosen in such a way as to fulfill the requirements of clarity and simplicity [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The variable

h, which depends on the lattice parameters, is associated with the most electronegative element, although it can be placed anywhere within parentheses. Electronegativities: X(Ni) = 1.91 [

16], X(Zn) = 1.65 [

16], X(Fe) = 1.96 [

16], X(O) = 3.44 [

16]. Thus, we see that if there are elements in the compound that do not have a specific physical observable, in our case, the Curie temperature, then the presence of these elements is taken into account by their atomic numbers and by their mass or molar amounts in the compound. In

Table 3, the Curie temperatures of ceramics, calculated by (1.3) with adjusted

q, are presented in comparison with the experimental temperatures from [

14]. For the resulting

q, we calculated

h (

Table 3). It can be seen that for a fixed

h for

x = 0 and 0.2, the parameter

q changes, although it is possible that both

q and

h are fixed in some ranges of external or internal parameters [

2,

3,

4,

5]. In this case, we multiply the weighted sum of the Curie temperatures by a variable depending on

x and atomic numbers. Do we have a coincidence again?

In [

3], we found that

h is proportional to the first derivative with respect to

x of the lattice parameters of the compound:

where

g is the gauge parameter,

a is the lattice parameter of ceramics (cubic [

14]). In table 3, we have only 3 points of

x, so it is difficult to understand the properties of

h, for this we consider the following complex compound.

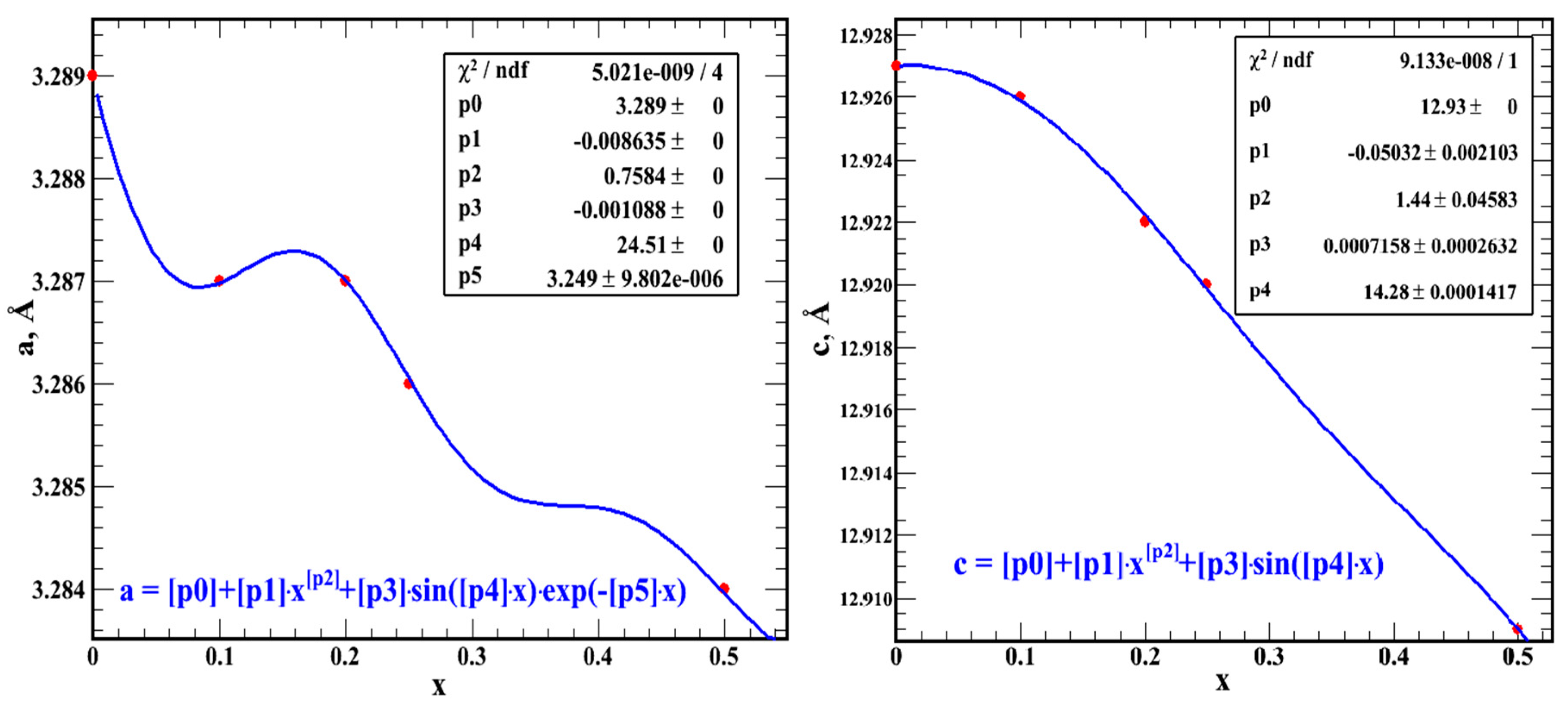

The chromium-intercalated compound Cr

xMoSe

2 [

17] has paramagnetic properties at room temperature, and at lower temperatures ( < 150 K) it has a magnetic ordering close to the ferromagnetic type, with always positive paramagnetic Curie temperatures

Θp (

Table 4). Of the three elements in Cr

xMoSe

2, only chromium has magnetic properties\transitions, but I did not find its paramagnetic Curie temperature, so I took its Néel temperature:

= 311 K [

18]. Probably,

Θp of chromium is absent, since even at temperatures above

the inverse magnetic susceptibility χ

–1 of

Cr decreases, χ

–1 decreases from –195°C to temperatures above 1440°C [

19]. Electonegativities: X(Cr) = 1.66 [

16], X(Mo) = 2.16 [

16], X(Se) = 2.55 [

16] so we relate the parameter

h to

Se in (1.4′):

where atomic numbers:

Cr = 24,

Mo = 42,

Se = 34. The parameters

q and

h change for all

x (

Table 4). The change in the lattice parameters

a and

c depending on

x for the hexagonal crystal structure of Cr

xMoSe

2 [

17] is also shown in

Table 4. The difference between the lattice parameters at the nearest x in

Table 4 shows that

h and

ai –

ai–1 and

ci – ci–1 change synchronously according to the periodic law, so we approximated the lattice parameters by periodic functions (

Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows that such a “good value” of χ

2/ndf (should be around 1) is due to two reasons. First, we need to have more data points. Secondly, we need a good theory, from which the law of changing the lattice parameters with

x follows organically, otherwise we fit the data to the function to which we want to fit the data. In any case, with such an approximation:

where

g1 and

g2 we still need to hack.

Thus, we have obtained that the magnetic properties of various materials can be represented by a molar-weighted sum of the magnetic properties of the elements of the materials. One has to conclude that either these are random coincidences that create the illusion of some kind of law, or these are manifestations of a real law, to clarify which a large database of physical properties of all elements of the periodic table, obtained with various values of internal and external parameters, is needed. With the help of this database, the prediction of a new complex compound with expected unique properties can be made not due to the intuition of the experimenter, as is currently done, but due to a clear knowledge of the relationships between the physical properties of the elements of a complex compound.

References

- Valu et al. The low-temperature heat capacity of the (Th,Pu)O2 solid solution. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 86 (2015) 194–206. [CrossRef]

- V. Kizka. Relationship Between the Mechanical Properties of an Irradiated Metal Alloy and the Mechanical Properties of the Irradiated Elements of the Alloy. Preprints 2023 2023061366. [CrossRef]

- [V. Kizka. Numerical Description of Melting/Solidification Temperature of Oxide Nuclear Fuels. Preprints 2023 2023050174. [CrossRef]

- V. Kizka. Thermal Conductivity of Carbides and Nitrides of Zr, Th and U:Numerical Approach. Preprints 2023 2023030403. [CrossRef]

- V. Kizka. Thermal Conductivity of ZrO2, ZrSiO4, (U,Zr)SiO4 and UO2: Numerical Approach. Preprints 2023 2023020406. [CrossRef]

- K.G. Gurtovoĭ and R.Z. Levitin. Magnetism of actinides and their compounds. Sov. Phys. Usp. 30 (1987) 827. [CrossRef]

- W. Suski. Magnetism of Uranium Intermetallics. Acta Physica Polonica A 91 (1997) 77. [CrossRef]

- D. Shoenberg and M. Uddin. The magnetic properties of antimony. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 32(3) (1936) 499–502. [CrossRef]

- S. Othmani, I. Chaaba, S. Haj-Khlifa, P. de Rango, D. Fruchart. Magnetic and Magnetocaloric Effect of Laves Phase Compounds Er(Fe0.8−xMn0.2−yCox+y)2 with x, y = 0.0 or 0.1. Metals 10 (2020) 1247. [CrossRef]

- Rudy J.M. Konings and Ondrej Beneš. The Thermodynamic Properties of the f-Elements and Their Compounds. I. The Lanthanide and Actinide Metals. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 39(4) (2010) 043102–1 – 043102–47. [CrossRef]

- J. Langner and J.R. Cahoon. Increase in the Alpha to Gamma Transformation Temperature of Pure Iron upon Very Rapid Heating. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 41(5) (2010) 1276–1283. [CrossRef]

- E.B. Zaretsky. Impact Response of Cobalt over the 300-1400 K Temperature Range. Journal of Applied Physics 108(8) (2010) 083525–1 – 083525–7. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Lawson, A.C. Larson, M.C. Aronson, S. Johnson, Z. Fisk, P.C. Canfield, J.D. Thompson, and R.B. Von Dreele. Magnetic and Crystallographic Order in α-Manganese. Journal of Applied Physics 76(10) (1994) 7049–7051. [CrossRef]

- V.N. Shut, S.R. Syrtsov, L.S. Lobanovskii et al. Crystal structure and magnetic properties of (Ni1–xZnx)Fe2O4 composition graded ceramic. Phys. Solid State 58 (2016) 1975–1980. [CrossRef]

- G. Schulze. Metallfhysik. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1967.

- A. L. Allred. Electronegativity Values from Thermochemical Data. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry 17(3-4) (1961) 215–221.

- V.G. Pleshchev, N.V. Selezneva. Magnetic Properties and Nature of Magnetic State of Intercalated CrxMoSe2 Compounds. Phys. Solid State 61 (2019) 339–344.

- Eric Fawcett. Spin-density-wave antiferromagnetism in chromium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 60 (1988) 209.

- T.R. McGuire and C.J. Kriessman. The Magnetic Susceptibility of Chromium. Phys. Rev. 85 (1952) 452.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).