1. Introduction

Our study is based on two factors. First, the company's board of directors (including independent board members) has an influence on the financial performance of the company. Second, the role of the three ESG pillars, namely the environmental pillar, the social pillar, and the governance pillar, and how they affect the above relationship has become the subject of debate among many researchers. In recent years, many authors have noticed the influence of board diversity on ESG practice (Boukattaya et al., 2022; Kahloul et al., 2022; Veltri et al., 2021). Independent directors have an important role in corporate governance (Eeckloo et al, 2004) because it helps firms improve oversight (Fama & Jensen, 1983) and reduce agency costs (Naciti, 2019). Independent directors are expected to expand the debate on the board, helping to increase creativity and innovation; improved problem-solving ability; promote the exchange of ideas, bringing to the board new knowledge and perspectives (Carter et al., 2003; Deloitte, 2019). Therefore, the relationship between independent board members and business performance has become a research issue of interest to many scholars.

Board diversity is classified into structural type, i.e. board independence (Aggarwal et al., 2019), and demographic type, i.e. gender, age, education level, nationality, and tenure (Ben-Amar et al., 2013). The role of the board includes supervisory, advisory, and advisory responsibilities that are relevant to improving business performance from both an agency and resource base perspective (lsidro & Sobral, 2015). In addition, the board of directors has enough dependent and independent directors, which allows them to exercise oversight responsibilities, deal with agency issues, and protect minority shareholders from major shareholders' appropriation (Villalonga et al., 2015). Therefore, board independence can sometimes be a useful complement to diversity and a necessary condition for effective governance (van Essen et al., 2012; Pandey et al, 2022). This helps independent board members which will improve the financial performance of the business.

Environment, Society, and Governance (ESG) is an investment philosophy and evaluation standard that derives from environmental protection, responsibility, and corporate governance rather than financial focus. It arose from corporate social responsibility (CSR), and was initially promoted by the voluntary movement of the public and non-profit organizations (Mar Miralles- Quiros et al., 2019). An ESG (Refinitiv) performance and disclosure assessment system has been steadily developed by Thomson Reuters. These assessments are usually performed by third-party rating agencies (Wong et al., 2021). It represents the company's level of involvement and performance in CSR activities. With increased regulatory enforcement and increased consumer awareness of environmental and social issues, ESG has become an important indicator of market participation. However, in previous studies, the relationship between ESG and firm performance presented different evidence (Gillan et al, 2021), mainly focusing on the causes and effects of ESG (Xu et al, 2021; Zhang et al, 2022). Studies on the mediating role of ESG in the relationship between independent board members and financial performance are relatively limited.

Therefore, this study focuses on providing theoretical and empirical support for the influence of independent board membership on financial performance under the mediation of three ESG components (environmental pillar, social pillar, and governance pillar). Previous research has largely ignored the mediating effects of ESG disclosure on the relationship between the independent director's ratio and financial performance, which has become increasingly important in a period where sustainability is the target of all businesses and countries around the world. This study attempts to contribute further insights by empirically investigating the mediating effects of the 3 ESG pillars on the relationship between board independence and the financial performance of the company.

Our experimental part is based on a sample of data from 173 Taiwanese companies that announced ESG from 2009 to 2021. We collect data from the Refinitiv Eikon data system designed by the Thomson Reuters organization. The results indicate that companies with a high percentage of independent directors have better financial performance. Furthermore, when viewed through the theoretical lens of stakeholders, the findings indicate that the three environmental, social, and governance pillars of the ESG between a mediating role in the relationship between the independent board member and the company's financial performance.

The author's research implies some refinement. First, the author is only interested in companies that have ESG disclosure because these companies are likely to be more sustainable than companies that do not. Second, the author examines the independence of the board of directors from the perspective of stakeholders and representatives to explain the impact of independent board members on the financial performance of the company. Third, the study shows the mediating role of ESG's three environmental, social, and governance pillars in relation to the company, thereby providing a deeper insight into sustainable development approaches for the company. Finally, the results and arguments of the study complement the academic contributions and encourage policymakers and board businesses to determine the proportion of independent board members in a manner that develops sustainably and improves the financial performance of the company.

The remainder of the research paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides the theoretical framework and hypothesis development.

Section 3 describes the research methods, data, techniques, and analysis in detail.

Section 4 reports the research results, section 5 is the discussion, and finally, section 6 is the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Independent Board Member and ESG

Stakeholder theory indicates that independent board members can represent stakeholders and will not be driven by interests within the organization (Kaymak & Bektas, 2017). In addition, the independence of the board of directors discourages behaviors that are not socially beneficial (Naciti, 2019), and encourages companies to fulfill environmental and social responsibilities. According to Foote et al. (2010), a company can succeed by practicing good governance principles and maintaining close relationships with society and the environment. Many previous studies have documented an effective corporate governance mechanism (including an independent board of directors) that encourages companies to engage in CSR practices and reporting (Cucari et al., 2018; Gallego- Alvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2020; Jizi, 2017; Pucheta-Martínez & Gallego- Alvarez, 2019), thus, positively affects CSR performance. Environmental, social, and governance scores have emerged as an important pillar of CSR in developing sustainable strategies that affect the financial performance of multinational companies (Eccles and Serafeim 2013). Consistent with the theory and previous studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a. Board independence is positively related to the environmental pillar

H1b. Board independence is positively related to the social pillar

H1c. Board independence is positively related to the governance pillar

2.2. Independent Board Member and Financial Performance

Eeckloo et al., (2004) indicate that the proportion of independent (non-executive) board members in the board of directors plays an important role in corporate governance. Regulators, researchers, and investors agree that increasing the number of independent directors on the board will objectively monitor management while pursuing the best interests of shareholders (Brandes et al., 2022). Agency theory suggests that the board of directors should include more independent directors to minimize management opportunism and agency conflicts (Shaukat et al., 2016). Consistent with agency theory, most governance rules also dictate that the board of directors should consist mostly of independent directors who do not hold managerial roles within the organization and its subsidiaries (Eeckloo et al, 2004). Fama & Jensen (1983) also believe that more independent board members will improve the firm's oversight and reduce agency costs (Naciti, 2019). Empirical evidence on the effectiveness of independent boards of directors is inconsistent. Some studies suggest that the more independent boards are present, the more effective oversight can be (Core et al., 1999; Goranova et al., 2010; Knyazeva et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016; Nguyen & Nielsen, 2010; Souther, 2021). For example, Knyazeva et al., (2013) suggest that there is a positive association between board independence and firm value. Board independence can increase firm value when taking into account endogenous factors and improve the accuracy of the firm value variable (Souther, 2021). Authors such as (Hamdan & Al Mubarak, 2017; Kumar & Sivaramakrishnan, 2008; Singh & Gaur, 2009) find a negative relationship between board independence and firm performance. Contrary to most assumptions about board independence, firm value can actually decrease as board independence increases (Kumar & Sivaramakrishnan, 2008). Board independence has a negative relationship with operating performance (Singh & Gaur, 2009) as well as with return on assets and return on equity based on accounting (Hamdan & Al Mubarak, 2017). However, other studies have not found evidence of a relationship between board independence and firm performance (Dalton et al., 1998; Bhagat & Black, 2001; Hermalin & Weisbach), 1991; Yer-mack, 1996).

In general, most of the previous studies have relatively comprehensively studied the independence of the board of directors. However, there is very little research on the relationship of independent directors to the financial performance of firms. Among the documents that the author found, only 7 documents study this relationship, only 3 documents show that the independence of management activities has a negative relationship with the company's performance, and the remaining 4 documents indicate no relationship. Therefore, to improve the missing research gap, the author believes that companies with a high percentage of independent directors on the board of directors will ensure the company's governance system works effectively, thereby improving the quality of the board's decisions, helping them to save costs and improve financial performance better, we develop the following hypothesis:

H2.

Independent Board Member is positively associated with financial performance.

2.3. The relationship between ESG practices and financial performance

ESG scores are classified as the added value of CSR practices in environmental, social, and governance activities. Since Taiwan has different conditions than other countries in the world, companies with high ESG levels require more investment. Therefore companies in Taiwan must allocate significant financial resources to practice ESG and improve their own capacity to achieve corporate efficiency. However, the costs associated with ESG enhancement are often not reflected in the financial performance of the business, which may not be carried out in the most efficient manner; it is not visible and the stakeholders of the company often do not really take it seriously.

According to Semenova and Hassel (2008), when an enterprise invests in ESG activities, it will create additional costs, which will affect the financial performance of the business. For example, excessive investments in reducing emissions or improving the use of natural resources (Rassier and Earnhart 2010), and some companies use outdated production technology, leading to the cost of switching to clean technologies being quite high. As a result, when these enterprises decide to invest in environmental initiatives, they find their economic resources compromised and their performance reduced because their environmental and social goals are not their primary goal (Duque-Grisales, E.; & Aguilera-Caracuel, J. 2021).

In addition, high levels of corruption in countries (political scandals and information manipulation) lead to a lack of trust among stakeholders in the corporate environment (Zhang et al. 2013), which forces businesses to invest more in corporate governance (e.g. hiring external auditors, amending regulations or creating more independence for the board) to demonstrate legitimacy in stakeholder questions (Reimann et al. 2012). In general, these initiatives are short-term and have high costs that will affect the company's performance.

Fiaschi et al. (2017) indicate that while companies have made efforts to improve social issues, they have not yet won the trust and loyalty of employees, consumers, and society. This can happen, when companies lack legitimacy due to operating in countries with poor institutions and poor reputations (Fiaschi et al. 2017). Therefore, the interests of enterprises are not recognized, as their socially beneficial activities are little known to the general public (Vives 2012). These activities do not attract stakeholders, do not improve the company's brand image, or provide incentives for companies to participate in this field.

The ESG score of an enterprise is evaluated based on 3 components: environment, society, and governance. Each of these sub-points has a relationship with the firm's FP, which is a subject of much interest in the literature. Friede et al. (2015) showed that ESG is determined by several components, each of which can have different relationships and effects on FP. But what aspect of this ESG score affects its relationship with FP? There is no consistency in the actual impact of ESG on FP. Several studies show that investing in ESG activities improves FP (Cahan et al 2015; Eccles et al 2014; Fatemi et al 2015; Rodriguez-Fernandez 2016; Wang and Sarkis, 2017), researchers Other studies have found negative effects (Branco and Rodrigues 2008; Brammer et al 2006; Lee et al 2009). For example, Lee et al. (2009) found that investing in ESG worsens FP and suggested that this may indicate a lower cost of equity for firms with high ESG scores. The third group of authors concluded that there was, in fact, no association between ESG scores and FP (Galema et al. 2008; Statman 2006; Horváthová 2010). Based on the above assertions, the author proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a: environmental pillar has an impact on financial performance

H3b: governance pillar has an impact on financial performance

H3c: social pillar has an impact on financial performance

2.4. Mediating effects of ESG

Feng and Wu, (2021) point out that the risk of climate change is increasing, and the stakeholder needs for sustainability and corporate social responsibility are also increasing, so ESG is essential to businesses can improve their value. From the people's point of view, businesses with high ESG efficiency will have the right perception of green and low-carbon production, helping to reduce material consumption in the production or recycling process of used materials (Chouaibi et al., 2022). In this case, people will be more inclined to support businesses that protect their living environment, so the business value will increase in their eyes. Jun et al., (2022) believe that CSR programs can promote intangible assets, attract potential customers, capture more market share, and create a good social image.

By moving from shareholder-centered governance towards stakeholder-centric governance, the interests of investors and non-investors are balanced, the level of risk is limited, and the firm's intrinsic value is protected (Di Tommaso and Thornton, 2020). Stemming from investor (Gregory, 2022) indicates that ESG enables people to understand CSR performance and sustainability prospects, which reduces ambiguity about the company's future. Focusing on ESG can attract investors and innovation stakeholders that provide competitive advantages for businesses such as cost savings and brand differentiation (Vadakkepatt et al., 2021). , which gives companies price and brand advantages.

Regarding corporate performance, Broadstock et al., (2021) recommend that ESG can improve a firm's performance in management and reduce portfolio risk. Because ESG is a soft control mechanism that influences risk-taking decisions in improving firm value by limiting undue risk. Pedersen et al., (2021) argue that firms with better ESG performance are more likely to reduce operational risks and are more likely to survive a crisis, which in turn protects reputations better. of the company. Therefore, from a risk perspective, ESG ensures that the business value does not collapse during the economic crisis, bringing life to the business. The lack of capital for business development has the root cause of asymmetric information between investors and enterprises (Chen and Yang, 2020). ESG has a significant impact on the cost of debt and reduces the cost of debt for the firm (Abdi and Omri, 2020). Furthermore, Christensen et al., (2022) reveal that ESG increases with higher volatility of returns and lower difficulty of obtaining external funding. Therefore, ESG will protect and enhance the business value in terms of solvency and profitability. Moreover, ESG can help the company to be valued higher and reduce the burden when the company is undervalued (Bofinger et al., 2022). Through this amplification effect, ESG can more effectively deliver business value. Together with the assumption of board membership independent of the ESG in section 2.1, this leads to the author's fourth hypothesis about the mediating mechanism of ESG performance.

H4.

Independent members of the board of directors can positively influence the financial performance of an enterprise through the three pillars of ESG: the environmental pillar, the social pillar, and the governance pillar.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Refinitiv database

The author collects data from Refinitiv also known as Refinitiv Eikon designed by the Thomson Reuters organization. The author chose Refinitiv because it is one of the most reliable international databases in the world. It contains one of the most comprehensive ESG databases in the industry, including over 450 different ESG indicators. This database is often used by researchers because it has a clear and transparent calculation method for the data.

The authors used ten data parameters in this study detailed in

Table 1. These data are independent board members; environmental pillar points; social pillar points; governance pillar points; boar size; total assets; market to book value; return on assets; return on equity; earnings per share. The data collected for this study was based on the latest Refinitiv framework as of June 2023. Refinitiv database (formerly Thomson Reuters) was used in previous research: banking sector (Esteban- Sanchez et al., 2017; Gangi et al., 2019; Miralles-Quir os et al., 2019; Bătae et al, 2021) or in other fields (Utz, 2017; Chollet and Sandwidi, 2018; Dorfleitner et al, 2015).

3.2. Sample

Our dataset contains 173 different Taiwanese companies that have ESG reports on The Refinitiv database between 2002 and 2022, however, when retrieving the data, most of the ESG data of the companies for the period from 2002-2007 is not available (NA), further the year 2007-2008 took place the global financial crisis so these years' data may not reflect the actual performance of the company. To ensure the balance and completeness of data, the author chooses 2009-2021 as the longest possible time period to perform data analysis (Data for 2022 has largely not been updated).

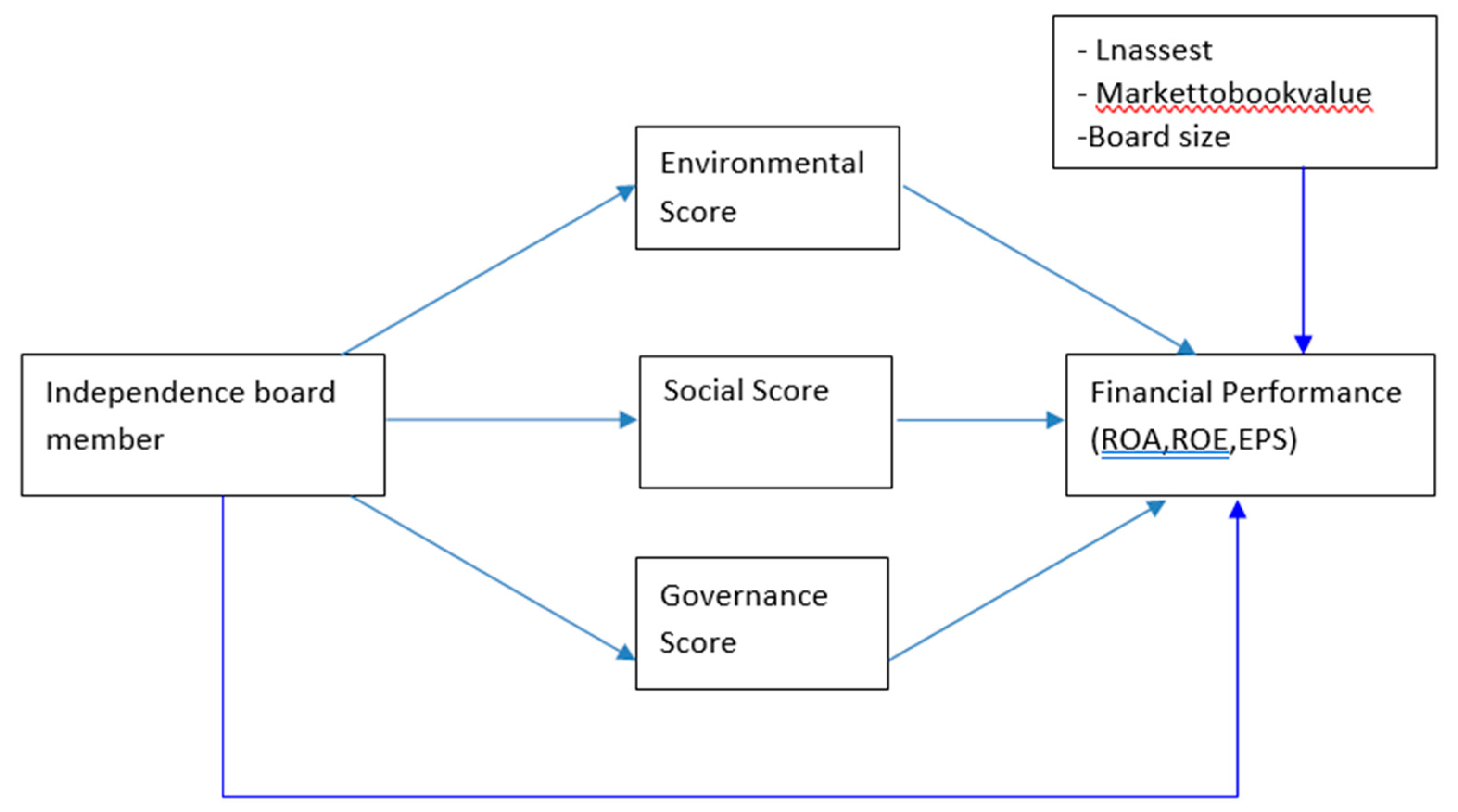

3.3. Statistical models and methods

Figure 1 shows the proposed model, including control variables to study the influence of independent board members on financial performance, in which 3 dimensions of ESG play an intermediary role. The equations of the models were estimated using the static panel data method using the Stata 14 software. The results for the static panel came from the xtgls command. Panel data often provide researchers with a large number of data points, increasing degrees of freedom and reducing multicollinearity between the independent variables. The advantage of fixed and random effects specifications is that they can control for unobserved heterogeneity without having to pinpoint the source of that heterogeneity.

The author uses a static panel data model for estimation after solving the problems of variable variance and autocorrelation using feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) estimates. The Hausman test is used to decide whether a fixed-effects or random-effects model is more appropriate. Experiments show that the fixed effects model is the best estimate.

3.4. Control variables

The author controls for a number of variables that can affect the financial performance of a firm such as firm size, market-to-book ratio, and board size. First, the author controls for firm size as measured by the natural logarithm of total assets (Hasan et al., 2018; Benlemlih et al., 2018). The writer expects a positive relationship between firm size and financial performance (Siueia et al,.2019). Previous studies have shown that large companies perform better financially than they have better management. Second, the author also controls for financial performance as measured by the market-to-book (MTB) ratio. Lewellen (1999) argues that low-growth firms are characterized by low stock prices and low market-to-book ratios. In addition, Bouslah et al (2013) consider companies with poor growth prospects (low MTB) to be more susceptible to market volatility. As a result, the author expects a positive relationship between financial performance and MTB. Finally, board size is measured by the total number of board members at the end of the financial year. Previous evidence suggests that firms with large boards will not achieve financial performance (Compton et al,.2019). Therefore, a negative relationship is expected between board size and financial performance.

4. Results

Table 2 and

Table 3 have shown descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables in the research model. The coefficients of the model are estimated using the static panel data method for the research period 2009 to 2021.

The results show that the percentage of independent board members has an impact on the three pillars of the ESG score and on the financial performance variables (

Table 4). In which, environmental, governance, and social pillars are dependent variables in model 1, model 2, and model 3, respectively. Financial performance variables such as ROA, ROE, and EPS are dependent variables, respectively in the model from 4 to 9. The role of the bridge between the independent variable and the dependent variable of the 3 ESG pillars is also shown very clearly in models 7, 8, and 9.

First of all, the author presents the results of the main effect of the independent variable to test hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1C, and H2. Then, the author presents the impact of the three environmental, governance, and social pillars related to hypothesis H3a, H3b, and H3c. Finally, the author analyzes the mediating role related to hypotheses H4c.

Table 4 shows us that the coefficient of the independent board member variable (IBM) is statistically significant, showing a positive impact on the environmental pillar, governance pillar, and social pillar score, and financial performance of the business. Therefore, we can confirm the hypothesis H1a, H1b, H1c and H2, consistent with previous studies that correspond to the hypothesis H1a, H1b and H1c (Cucari et al., 2018; Gallego- Alvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2020; Jizi, 2017; Pucheta-Martínez & Gallego- Alvarez, 2019) ) and H2 is (Pucheta-Mar-tínez & Gallego-Alvarez, 2020; Wahid, 2019). The higher the proportion of independent members on the board of directors, the higher will help the company performs the function of monitoring and organizing to exercise control over the management in a better way. This will increase ESG practices in the business, which will help businesses reduce risks in the long term, promote innovation and improve efficiency in sustainable and cost-effective operations, strengthen their reputable brand, and attract loyal customers.

Regarding the influence of the three pillars of environment, governance, and society on the financial performance of the enterprise, the coefficients are statistically significant, but only the coefficient of the social pillar has a positive coefficient and the other two coefficients have negative coefficients. This helps us to confirm the hypothesis H3a, H3b and H3c consistent with previous studies (Wang and Sarkis, 2017; Lee et al 2009). The results show that the practice of ESG standards in enterprises has an impact on the financial performance of enterprises.

Models 1, 2, and 3 show the regression results of the board member variable for 3 pillars, environmental, governance, and social (intermediate variables of the model). Models 4, 5, and 6 show the impact of 3 pillars of ESG with financial performance variables ROA, ROE, and EPS. Finally, models 7, 8, and 9 show the regression results of the combined impact of IBM, EnPS, GPS, LA, MBV, and BS on the financial performance of the business. The results of these 1, 2 and 3 regression models show that the coefficients of the IBM variable are quite positive, respectively β1=0.208, β2=0.366, and β3=0.262, respectively. However, compared with the coefficients of IBM in models 7 (β7=0.011), 8 (β8=0.059) and 9 (β9=0.031) it has been weakened. Therefore, when the impact of the 3 pillars of ESG on the model, the influence of IBM on ROA, ROE, and EPS is reduced, indicating that the performance of the 3 pillars (environment, governance, and society) plays a role part of the relationship between IBM and financial performance, which corroborates hypothesis H4.

5. Discussion

5.1. Academic Implications

This study has the following implications. The findings of this study focus on companies that report on the environmental pillar, social pillar, and governance pillar of Taiwanese companies, implying that the independent board member has an important role in corporate governance Eeckloo et al., (2004). Because the author's study only focuses on Taiwanese ESG reporting companies, it is questionable whether this holds true for Taiwanese ESG non-reporting companies. And the role of the independent director must be true for other countries or regions in the world. The implication is that scientists can do more research on the independent member of the board because it is really important. In addition, it is necessary to be more specific because previous empirical studies have shown that there are divergent results between the proportion of independent board members and CSR practices and financial performance, which is a positive relationship, a negative relationship, and no relationship at all. So what percentage of independent directors on the board is good, to what extent has a negative impact, has a positive impact, and is not related to corporate social responsibility practices and financial performance? This is a problem that needs to be studied more deeply by scientists.

5.2. Practical Implication

For the company, the independent director is always an indispensable part. So how to make use of it is a very important thing in corporate governance. The independent director can be said to be a double-edged sword for the development of the company. It can help the company to grow quickly and sustainably because it increases the monitoring capacity of the company (Knyazeva et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016; Nguyen & Nielsen, 2010; Souther, 2021), reduces agency costs (Naciti, 2019) and improve corporate governance (Aboody and Lev 2000; Johnson and Greening 1999; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Also, independent directors can improve CSR practices in enterprises (Cucari et al., 2018; Gallego- Alvarez & Pucheta-Martínez, 2020; Jizi, 2017; Pucheta-Martínez & Gallego- Alvarez, 2019) and bring in significant external resources, such as external networking, expertise, and political connections (e.g. Carpenter and Westphal 2001; Hillman et al. 2009). This helps to improve the reputation and trust of the public and the state of the company.

However, the independent director, if used improperly, can waste resources and have negative effects on the business. Kumar & Sivaramakrishnan, (2008) say that increased board independence can reduce the value of the company. Pathan and Faff (2013) also find evidence against board independence, reporting that small boards and in-house directors perform better in US banks' parent companies. In addition, it has a negative relationship with firm performance (Singh & Gaur, 2009), and ROA and ROE (Hamdan & Al Mubarak, 2017).

5.3. Government Policy Implication

The important role of board independence has been proven. A question arises, what the state and managers will have to do to maximize the role of the company's independent director? There are up to set some standards, regulations, or standards for members who can become independent directors of the company. For example, the independent director of an enterprise has at least one person from a government agency, or these people may be people with good reputations in society or these people must have how specific expertise, to help businesses while helping the government and society. It is a difficult question for regulators, but much of this will bring positive effects to a country if it is studied carefully and properly.

5.4. Limitations and Future Recommendations

This study may also have some limitations. First, it is likely that I have overlooked a few aspects that, according to previous experimental and theoretical research, could change a firm's performance. Second, in this study, we only consider companies that report Taiwan's ESG on the Refinitiv data system. In the future, other studies can be extended to companies in major economies around the world, to make the study more generalizable. Finally, we only use ROA, ROE, and EPS as metrics for financial performance, which leads to limitations for the study of non-publicly traded companies. In further studies, the researchers may use a more diverse approach to data analysis, to investigate how independent board members interact with ESG and financial performance.

In addition, the author identifies potential future research directions. First, we only focused on ESG reporting companies in Taiwan, this study may in the future examine other board compositions under ESG regulation in relation to financial performance, and in the broader world economy. Because similar findings may be true for one country, but not for another. In addition, we also recommend that it is possible to further study the dimensions that make up the environmental pillar, the social pillar, and the governance pillar, in order to identify more accurately and specifically each factor that is related to financial performance.

6. Conclusion

The author investigates the relationship between board membership ratio and corporate financial performance, as well as the impact of the three ESG pillars on this process. We examine the role of independent board members in affecting corporate financial performance using a sample of Taiwanese firms currently reporting ESG from 2009 to 2020. Based on agency theory and related party theory, the author shows that independent board members have a significant influence on the financial performance of the business. We discover a positive and meaningful relationship between independent board membership and financial performance. It shows that the board of directors, especially the independent board of directors, has a positive impact on corporate performance (Aggarwal et al., 2019). A panel consisting of more independent members has more cognitive abilities thus making better decisions (Adams et al., 2015). It is also believed that more independent members of the board of directors will improve corporate oversight and reduce agency costs (Naciti, 2019). This will improve the financial performance of the company. In addition, ESG disclosure has a moderating and partial effect on the relationship between Independent Directors Ratio and financial performance.

References

- Abdi, H.; Omri, M.A.B. Web-based disclosure and the cost of debt: MENA countries evidence. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 2020, 18, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboody, D.; Lev, B. Information asymmetry, R&D, and insider gains. The journal of Finance 2000, 55, 2747–2766. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.B.; de Haan, J.; Terjesen, S.; van Ees, H. Board diversity: Moving the field forward. Corporate Governance-An International Review 2015, 23, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Jindal, V.; Seth, R. Board diversity and firm performance: The role of business group affiliation. International Business Review 2019, 28, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bătae, O.M.; Dragomir, V.D.; Feleagă, L. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: A European study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 290, 125791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Environmental and social disclosures and firm risk. Journal of business ethics 2018, 152, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Francoeur, C.; Hafsi, T.; Labelle, R. What makes better boards? A closer look at diversity and ownership. British Journal of Management 2013, 24, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Black, B. The non-correlation between board independence and long-term firm performance. J. CorP. l. 2001, 27, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofinger, Y.; Heyden, K.J.; Rock, B. Corporate social responsibility and market efficiency: Evidence from ESG and misvaluation measures. Journal of Banking & Finance 2022, 134, 106322. [Google Scholar]

- Boukattaya, S.; Ftiti, Z.; Ben Arfa, N.; Omri, A. Financial performance under board gender diversity: The mediating effect of corporate social practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2022, 29, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, K.; Kryzanowski, L.; M’zali, B. The impact of the dimensions of social performance on firm risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 2013, 37, 1258–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financial management 2006, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Social responsibility disclosure: A study of proxies for the public visibility of Portuguese banks. The British accounting review 2008, 40, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, P.; Dharwadkar, R.; Ross, J.F.; Shi, L. Time is of the essence!: Retired independent directors’ contributions to board effectiveness. Journal of Business Ethics 2022, 179, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Finance research letters 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahan, S.F.; Chen, C.; Chen, L.; Nguyen, N.H. Corporate social responsibility and media coverage. Journal of Banking & Finance 2015, 59, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial review 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Yang, S.S. Do investors exaggerate corporate ESG information? Evidence of the ESG momentum effect in the Taiwanese market. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 2020, 63, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, P.; Sandwidi, B.W. CSR engagement and financial risk: A virtuous circle? International evidence. Global Finance Journal 2018, 38, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S.; Chouaibi, J.; Rossi, M. ESG and corporate financial performance: the mediating role of green innovation: UK common law versus Germany civil law. EuroMed Journal of Business 2022, 17, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? The case of ESG ratings. The Accounting Review 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Y.L.; Kang, S.H.; Zhu, Z. Gender stereotyping by location, female director appointments and financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics 2019, 160, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, J.E.; Holthausen, R.W.; Larcker, D.F. Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. Journal of financial economics 1999, 51, 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucari, N.; Esposito De Falco, S.; Orlando, B. Diversity of board of directors and environmental social governance: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2018, 25, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, D.R.; Daily, C.M.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Johnson, J.L. Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic management journal 1998, 19, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte, L.L. P. (2019). Missing pieces report: The 2018 board diversity census of women and minorities on Fortune 500 boards.

- Di Tommaso, C.; Thornton, J. Do ESG scores effect bank risk taking and value? Evidence from European banks. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 2286–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G.; Halbritter, G.; Nguyen, M. Measuring the level and risk of corporate responsibility–An empirical comparison of different ESG rating approaches. Journal of Asset Management 2015, 16, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. Journal of Business Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management science 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Serafeim, G.; Seth, D.; Ming, C.C. Y. The Performance Frontier: Innovating for a Sustainable Strategy: Interaction. Harvard business review 2013, 91, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckloo, K.; Van Herck, G.; Van Hulle, C.; Vleugels, A. From Corporate Governance To Hospital Governance.: Authority, transparency and accountability of Belgian non-profit hospitals’ board and management. Health Policy 2004, 68, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. Journal of cleaner production 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. The journal of law and Economics 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Fooladi, I.; Tehranian, H. Valuation effects of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Banking & Finance 2015, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, Z. ESG disclosure, REIT debt financing and firm value. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 2021, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaschi, D.; Giuliani, E.; Nieri, F. Overcoming the liability of origin by doing no-harm: Emerging country firms’ social irresponsibility as they go global. Journal of World Business 2017, 52, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of management Journal 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, J.; Gaffney, N.; Evans, J.R. Corporate social responsibility: Implications for performance excellence. Total Quality Management 2010, 21, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of sustainable finance & investment 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar]

- Galema, R.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment. Journal of Banking & Finance 2008, 32, 2646–2654. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Pucheta-Martínez, M.C. Corporate social responsibility reporting and corporate governance mechanisms: An international outlook from emerging countries. Business Strategy & Development 2020, 3, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gangi, F.; Meles, A.; D'Angelo, E.; Daniele, L.M. Sustainable development and corporate governance in the financial system: are environmentally friendly banks less risky? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.P. ESG scores and the response of the S&P 1500 to monetary and fiscal policy during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Review of Economics & Finance 2022, 78, 446–456. [Google Scholar]

- Goranova, M.; Dharwadkar, R.; Brandes, P. Owners on both sides of the deal: Mergers and acquisitions and overlapping institutional ownership. Strategic Management Journal 2010, 31, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: The mediating role of productivity. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 149, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermalin, B.E.; Weisbach, M.S. The effects of board composition and direct incentives on firm performance. Financial management 1991, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváthová, E. Does environmental performance affect financial performance? A meta-analysis. Ecological economics 2010, 70, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M. The influence of board composition on sustainable development disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment 2017, 26, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Shiyong, Z.; Yi, T. Does ESG disclosure help improve intangible capital? Evidence from A-share listed companies. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 858548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.M. M.; Al Mubarak, M.M. S. The impact of board independence on accounting-based performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 2017, 33, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of management 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahloul, I.; Sbai, H.; Grira, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility reporting improve financial performance? The moderating role of board diversity and gender composition. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 2022, 84, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymak, T.; Bektas, E. Corporate social responsibility and governance: Information disclosure in multinational corporations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2017, 24, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazeva, A.; Knyazeva, D.; Masulis, R.W. The supply of corporate directors and board independence. The Review of Financial Studies 2013, 26, 1561–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sivaramakrishnan, K. Who monitors the monitor? The effect of board independence on executive compensation and firm value. The Review of Financial Studies 2008, 21, 1371–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Faff, R.W. Corporate sustainability performance and idiosyncratic risk: A global perspective. Financial Review 2009, 44, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, L. Removing vacant chairs: Does independent directors’ attendance at board meetings matter? Journal of Business Ethics 2016, 133, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellen, J. The time-series relations among expected return, risk, and book-to-market. Journal of financial Economics 1999, 54, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lsidro, H.; Sobral, M. The effects of women on corporate boards on firm value, financial performance, and ethical and social compliance. Journal of business ethics 2015, 132, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Redondo Hernández, J. ESG performance and shareholder value creation in the banking industry: International differences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Redondo-Hernández, J. The impact of environmental, social, and governance performance on stock prices: Evidence from the banking industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.D.; Nielsen, K.M. The value of independent directors: Evidence from sudden deaths. Journal of financial economics 2010, 98, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Kumar, S.; Post, C.; Goodell, J.W.; García-Ramos, R. Board gender diversity and firm performance: A complexity theory perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S.; Faff, R. Does board structure in banks really affect their performance? Journal of Banking & Finance 2013, 37, 1573–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Fitzgibbons, S.; Pomorski, L. Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier. Journal of Financial Economics 2021, 142, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassier, D.G.; Earnhart, D. Does the porter hypothesis explain expected future financial performance? The effect of clean water regulation on chemical manufacturing firms. Environmental and Resource Economics 2010, 45, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, F.; Ehrgott, M.; Kaufmann, L.; Carter, C.R. Local stakeholders and local legitimacy: MNEs' social strategies in emerging economies. Journal of international management 2012, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 2016, 19, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.; Hassel, L.G. Financial outcomes of environmental risk and opportunity for US companies. Sustainable Development 2008, 16, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Board attributes, corporate social responsibility strategy, and corporate environmental and social performance. Journal of Business Ethics 2016, 135, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.A.; Gaur, A.S. Business group affiliation, firm governance, and firm performance: Evidence from China and India. Corporate Governance: An International Review 2009, 17, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siueia, T.T.; Wang, J.; Deladem, T.G. Corporate Social Responsibility and financial performance: A comparative study in the Sub-Saharan Africa banking sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 226, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souther, M.E. Does board independence increase firm value? Evidence from closed-end funds. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2021, 56, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statman, M. Socially responsible indexes: Composition, performance, and tracking error. Journal of portfolio Management 2006, 32, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, S. (2017). Over-investment or risk mitigation? Corporate social responsibility in Asia-Pacific, Europe, Japan, and the United States. Review of Financial Economics.

- Vadakkepatt, G.G.; Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V.; Zinn, W.; Beitelspacher, L.; Aloysius, J. . & Reilman, J. Sustainable retailing. Journal of Retailing 2021, 97, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen, M.; van Oosterhout, J.H.; Carney, M. Corporate boards and the performance of Asian firms: A meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2012, 29, 873–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, S.; Mazzotta, R.; Rubino, F.E. Board diversity and corporate social performance: Does the family firm status matter? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental management 2021, 28, 1664–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R.; Trujillo, M.A.; Guzmán, A. Governance of family firms. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2015, 7, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A. Is socially responsible investment possible in Latin America? Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2012, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.C.; Batten, J.A.; Ahmad, A.H.; Mohamed-Arshad, S.B.; Nordin, S.; Adzis, A.A. (2021). Does ESG certification add firm value? Financ Res Lett 39: 101593.

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. Journal of cleaner production 2017, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, F.; Shang, Y. R&D investment, ESG performance and green innovation performance: evidence from China. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 737–756. [Google Scholar]

- Yermack, D. Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal of financial economics 1996, 40, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y. How does firm ESG performance impact financial constraints? An experimental exploration of the COVID-19 pandemic. The European journal of development research 2023, 35, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Zhu, H.; Ding, H.B. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: An empirical investigation in the post Sarbanes-Oxley era. Journal of business ethics 2013, 114, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).