1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide and is a major contributor to reducing the quality of life (Stamilio and Scifres, 2014). The number of deaths with CVD increases steadily, from 12.1 million in 1990 to 18.6 million in 2019, accounting for 1/3 of the total number of deaths globally (Roth et al., 2020). China is one of the countries with a high burden of CVD. The number of deaths from CVD accounts for 40% of the total deaths, among which, the number of deaths of atherosclerosis cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) accounts for 61% of the total deaths of CVD. In the past 20 to 30 years, the incidence of ASCVD is still on rising, causing a huge economic burden on the country's medical and health system (Zhao et al., 2019).

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a chronic progressive disease caused by lipometabolic disorder and chronic low-grade inflammation. It is the result of complex environmental and genetic factors (Xu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2018). Several studies showed that genetic variation only accounts for a small part of the risk of developing AS, and environmental factors play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of AS. Diet is the most important environmental factor, and metabolic abnormalities caused by changing in diet structure are one of the main reasons for the development of AS (Laitinen et al., 2020). Long-term consumption of a diet inched in high fat, high cholesterol, and high sugar will cause lipid metabolism disorders, increase the risk of AS and promote plaque development in patients with AS (Acosta et al., 2021).

The occurrence and development of AS are involved in the accumulation of vascular lipids, activation of the immune system, inflammation, oxidative stress and oxidized low-density lipoprotein, activation of endothelial cells, the proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells and activation of macrophages, and formation of foam cells. In the early stage of AS lesions, endothelial cells are activated by various injury factors such as intravascular free radicals and abnormal lipid accumulation, thus leading to functional disorders, mainly lipid metabolism disorders. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was oxidized to ox⁃LDL by low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLR). The ox-LDL may bind to endothelial cell surface lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX⁃1) to enter endothelial cells and activate endothelial cells to produce an inflammatory cascade, the interplay of lipid metabolism disorder and inflammatory response promotes the atherogenic development (Lecce et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2018).

The emergence of metabolomics provides a new direction for the study of the pathological mechanism of AS. The differences in the levels of identified metabolites (such as amino acids, lipids, bile acids, etc.) are closely related to the occurrence and development of AS (Iida et al., 2019). However, these small molecule metabolites have the potential to become biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases and the metabolic mechanism of AS has not been fully understood.

Tibetan minipigs are characteristic experimental animals in China. The organ systems of Tibetan minipig and human beings are not only similar in morphology, but also basically the same in physiological function, especially the cardiovascular system, lipid metabolism structure, and AS lesion site. Therefore, they are currently recognized AS suitable model animals for the study of AS (Shim et al., 2016). Our previous study found that Tibetan minipigs are easy to form AS under the induction of a high-fat diet and a variety of risk factors for the formation of AS could be observed (Yang et al., 2022; 郁晨 et al., 2019). This AS model of central obesity is accompanied by insulin resistance and hypertension characterized by chronic inflammation and lipid metabolism disorder, which is very similar to the etiological and pathological characteristics of human AS formation (陈民利, 2018). Therefore, in this study, the AS model of Tibetan minipigs was adopted to study the characteristics of the serum metabolites during the occurrence and development of AS, to screen the relevant differential metabolites and their related pathways, and explain the relevant metabolic mechanism during the occurrence and development of AS.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Laboratory animal

Conventional male Tibetan minipigs, aged 4-5 months, weighing 8-12 kg, 12 pigs, were purchased from Dongguan Songshan Lake Pearl Laboratory Animal Technology Co., LTD. [SCXK (yue) 2017-0030], Certificate No. : 44410500000286. All Tibetan minipigs were raised in the ordinary environment miniature pig laboratory of the Animal Experimental Research Center of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University [SYXK (zhe) 2018-0012], ambient temperature, 22±1 ℃, ambient relative humidity, 40%-60%, the light and dark alternated for 12 h/12 h, the pigs were fed freely, and the pigs were fed two meals a day. All feeding and animal experiment procedures of this study were approved by the Laboratory Animal Management and Use Committee of the Animal Experimental Research Center of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University and strictly abide by the welfare of laboratory animals (IACUC approval number: 20191021-10).

2.2. Animal serum and Aortic vessel

They were fed with a high-fat and high-cholesterol (HFC) diet (HFC feed formula: 15% shortening, 10% yolk powder, 1.5% cholesterol, 0.5% choline, 73.0% basal diet) after 4, 8, 16, and 28 weeks, fasting for 16 h, AS model group (Model group) was compared with the normal control group(NC group) at 28 weeks, 5 mL of blood was collected from the anterior vena cava of Tibetan minipigs in NC group, 3000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was taken by centrifugation. All supernatants were stored in the refrigerator at -80 ℃.

After feeding the HFC diet for 28 weeks, Tibetan minipigs were given excessive anesthesia and bloodletting, and the blood vessels from the aortic arch to the iliac part of the abdominal aorta were taken, the excess fat around the vessels was removed, and fixed in 10% neutral formaldehyde for 24 h.

2.3. Non-targeted metabolomics analysis

All samples were melted at 4 ° C. 100 µL from each sample was placed in a 2 mL centrifuge tube; Each centrifuge tube was added with 400 µL methanol (-20 ℃), shook for 60 s, and thoroughly mixed. After centrifugation at 12000 rpm and 4 ℃ for 10 min, all the supernatant was taken and transferred to a new 2 mL centrifuge tube for vacuum concentration and drying. 150µL 2-chlorophenylalanine (4 ppm) 80% methanol solution was redissolved, and the supernatant was filtered by 0.22µm membrane to obtain the samples to be tested. 20µL was taken from each sample to be tested and mixed into QC samples (QC: quality control, used to correct the deviation of analysis results of mixed samples and errors caused by the analysis instrument itself) and the remaining samples to be tested were used for LC-MS detection.

2.4. Data analysis

Data preprocessing: the Proteowizard software will convert the original data obtained from the computer into mzXML format (xcms input file format); R's XCMS package was used to filtrate peaks identification, peaks filtration and peaks alignment. The data matrix including mass to charge ratio (m/z), retention time and intensity was obtained that was to obtain metabolomics.

All charts using R language statistics drawn, with ±SEM showed that between two groups to compare the t-test test, P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Identification of differential abundance metabolites in the development of AS based on the untargeted metabolome

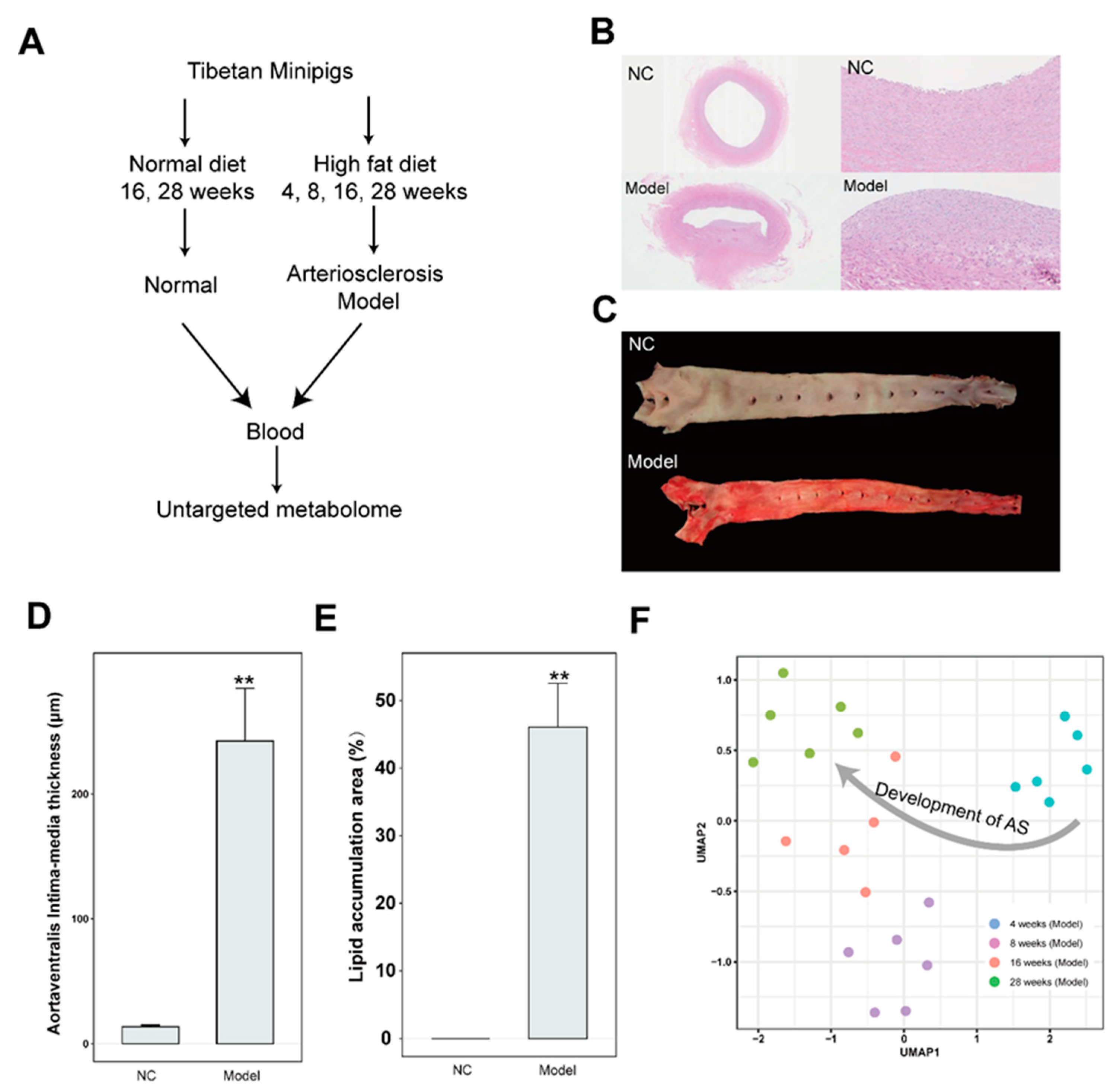

To investigate the metabolic characteristics of AS, the Tibetan minipig was used for building the AS model by feeding the high-fat diet. The blood was collected at 4, 8, 16, and 28 weeks in AS group and at 16 and 28 weeks in the control groups which is fed the normal diet for metabolites identification (

Figure 1A). Within four weeks of high-fat induction, the serum lipid level of Tibetan minipigs is significantly increased and the hyperlipidemia was gradually developing to form the AS plaque at 16 weeks, eventually, a mature plaque was formed at 28 weeks. It is mainly distributed in the abdominal aorta and coronary artery, which is similar to the occurrence and development process and lesion site of human clinical AS (

Figure 1B). There are obvious AS lesions. Compared with the NC group, the Sudan IV staining of aortic vessels showed that, obvious lipid accumulation was observed in the aortic arch of the AS group at 28 weeks (

Figure 1B). Based on semi-quantitative analysis showed that, the aortaventralis intra-media thickness and Lipid accumulation area were significantly increased in AS group compared with NC group (

Figure 1C). Moreover, UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) (Becht et al., 2018) analysis of metabolites in AS group showed that samples from 4, 8, 16 and 28 weeks were clustered respectively. It implied that AS lesion was gradually formed from the early stage to the late stage by feeding a high-fat diet.

3.2. The characteristics of metabolites enriched in the AS model group

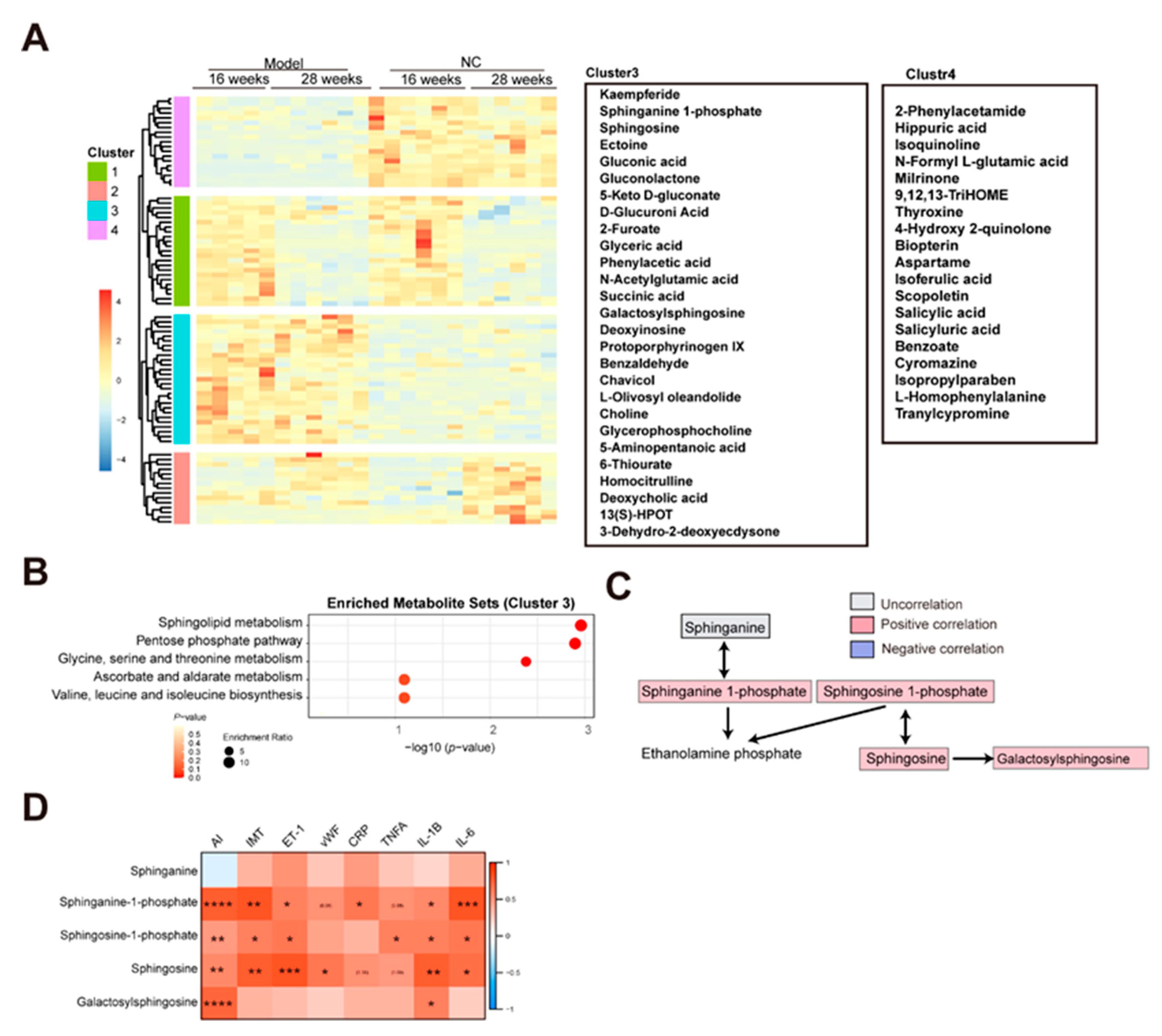

To investigate the metabolites associated with the AS, a hierarchical clustering analysis is performed using the metabolites in the NC and model group at 16 and 28 weeks after filtering with adjusted p-value < 0.05 of ANOVA test. Resultantly, four clusters were observed (

Figure 2A). Based on heat map analysis, the metabolites in clusters 1 and 2 were associated with changing of time and the metabolites in clusters 3 and 4 were associated with AS. A total of 27 metabolites in cluster 3 were increased and 19 metabolites in cluster 4 were decreased in the model group compared with the NC group, regardless of 16 and 28 weeks (

Figure 2A). Then, the metabolites pathway enrichment analysis was performed by MetaboAnalyst (Pang et al., 2022). Resultantly, three pathways such as sphingolipid metabolism, pentose phosphate pathway, and Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism were enriched in AS cluster (

Figure 2B). Increasing evidence showed that the sphingolipid metabolism was associated with AS by promoting inflammatory responses, cholesterol efflux, and aggregation of particles in the aorta (Christoffersen et al., 2011; Schissel et al., 1996; Skoura et al., 2011). In this study, the three sphingolipid metabolism-related metabolites including sphinganine 1-phosphate, sphingosine 1-phosphate, and sphingosine were enriched in the AS cluster (

Figure 2C). Then, the association between sphingolipid metabolism and the AS index, IMT (intima-media thickness), endothelial injury markers (ET-1, vEF), and inflammatory markers (CRP, TNFA, IL-1B, and IL-6) were analyzed. Resultantly, significant positive correlations between sphingolipid metabolism and AS index, endothelial injury, and inflammation were observed (

Figure 2D).

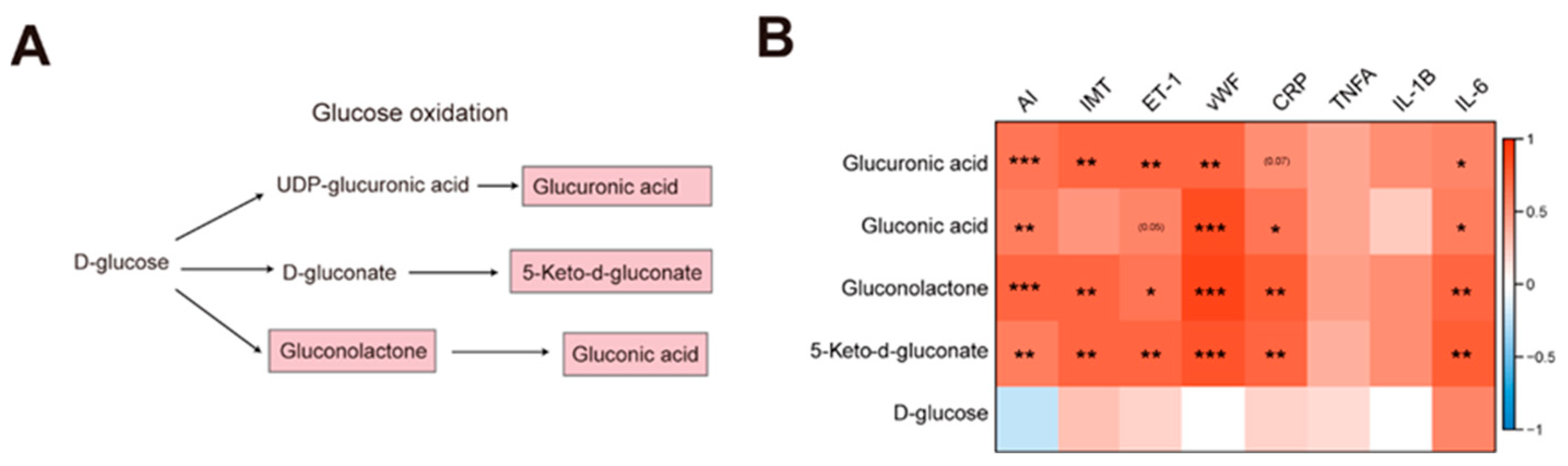

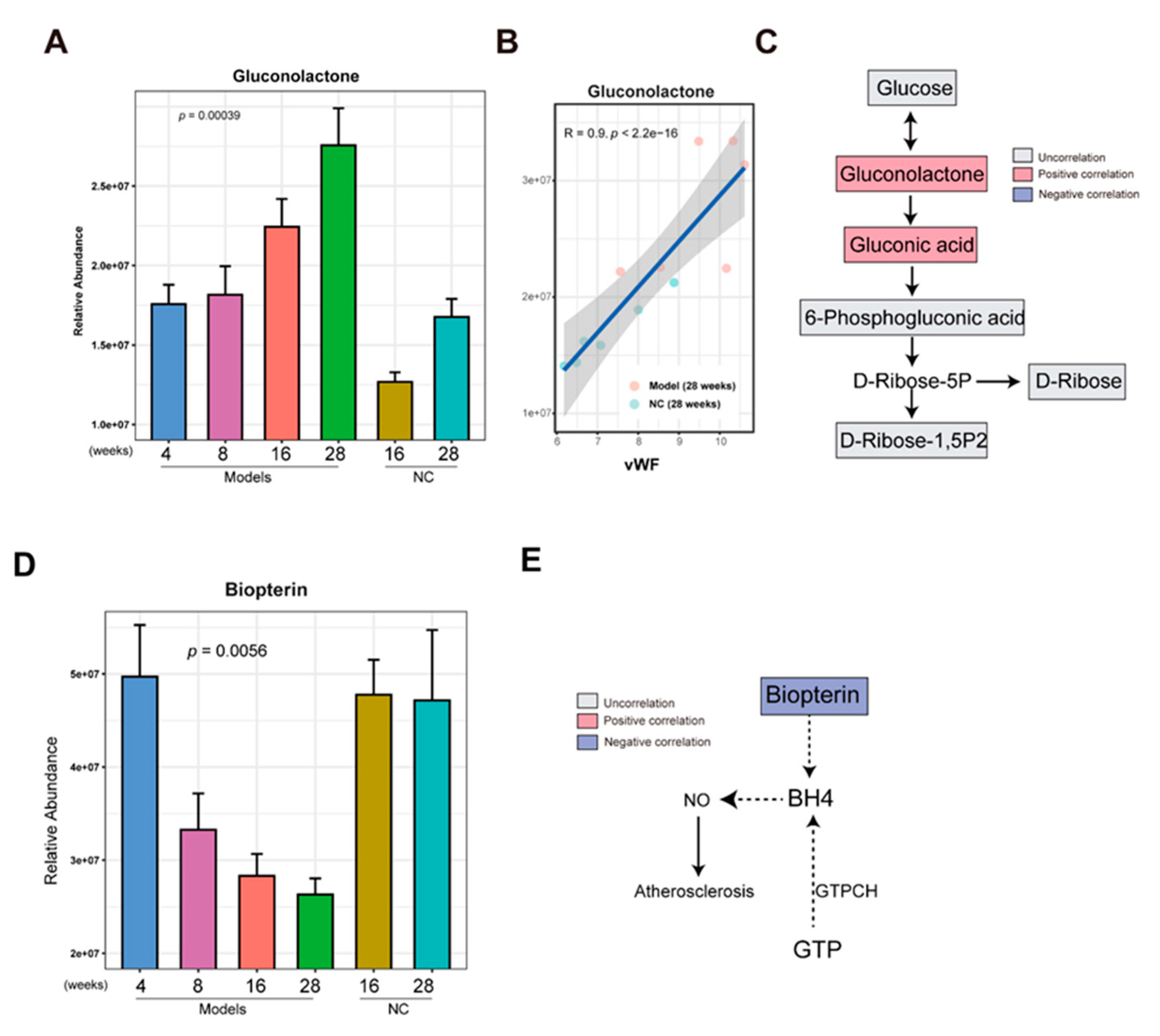

Apart from that, several products of glucose oxidation were identified in the AS cluster, including glucuronic acid, 5-keto-d-gluconate, gluconolactone, and gluconic acid (

Figure 3A). The D-glucose can be oxidized to D-gluconate which can be converted to two 5-keto-D-gluconates (5KGA) and 2-keto-D-gluconate (2KGA) (Toyama et al., 2007). The enriched gluconolactone could be from glucose oxidation by glucose oxidase and lead to produce FADH

2 from FAD and the gluconic acid can be from hydrolysis of gluconolactone catalyzed by lactonase or spontaneously (Wong et al., 2008). The glucuronic acid can be converted from UDP-glucuronic acid which is oxidized from UDP-glucose by NAD+ and UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (Wang et al., 2019). These products of glucose oxidation exhibited a significant positive correlation with AS index, IMT, endothelial injury (ET-1 and vWF), and inflammation (CRP and IL-6) (

Figure 3B). In atherosclerosis, excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) were generated to induce the oxidative stress which is implicated in vascular injury and inflammation (Kattoor et al., 2017). The oxidative stress could contribute to glucose oxidation.

3.3. Phenylalanine metabolism was reduced in the AS model group

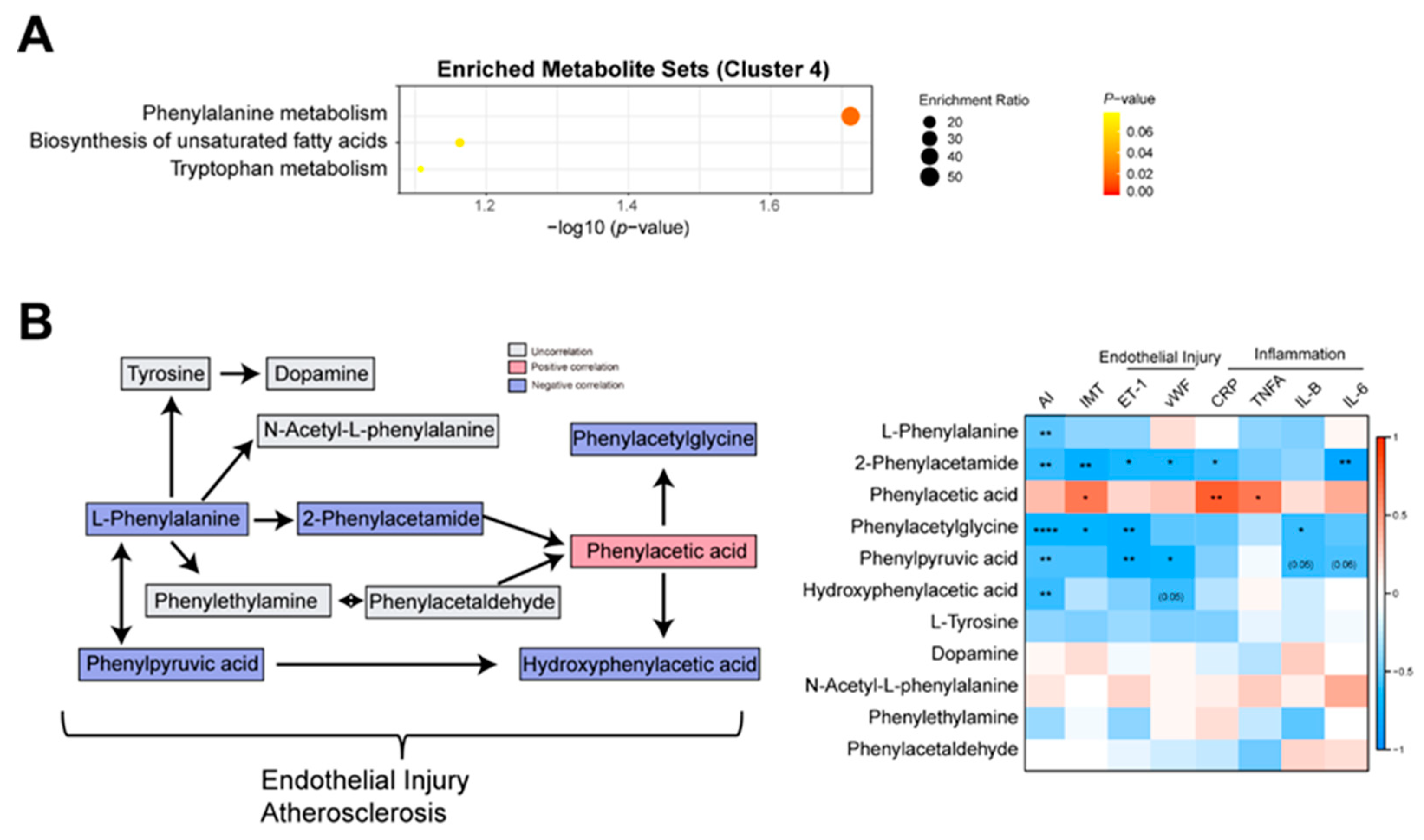

Based on enrichment analysis, the phenylalanine metabolism was reduced in the AS group (

Figure 4A). Then, we analyzed the correlations between AS index and phenylalanine metabolism-related metabolites. The negative correlations between AS index and phenylalanine metabolism-related metabolites such as L-Phenylalanine, Hydroxyphenylacetic acid, Phenylacetylglycine, Phenylpyruvic acid, and 2-Phenylacetamide were observed (

Figure 4B,C). Then, we performed the correlation analysis between these metabolites and IMT, endothelial injury markers (ET-1, vEF), and inflammatory markers (CRP, TNFA, IL-1B, and IL-6). Resultantly, Phenylacetylglycine, Phenylpyruvic acid, and 2-Phenylacetamide were negatively correlated with ET-1, and Hydroxyphenylacetic acid, Phenylpyruvic acid, and 2-Phenylacetamide were negatively correlated with vWF (

Figure 4C). It implied that phenylalanine metabolism related metabolites were associated with vascular injury. Another piece of evidence showed that 3-hydroxyphenyl acetic acid could reduce blood pressure and vascular injury through the release of nitric oxide (Dias et al., 2022). Taken together, the phenylalanine metabolism dysfunction could influence vascular injury and AS by the release of nitric oxide.

3.4. Gluconolactone was enriched in the late stage of AS

In a previous analysis, we found that the metabolites in cluster 3 were enriched in the model group. To determine whether these metabolites gradually increase in the development of AS, the abundance of metabolites in Cluster 3 in the model group at 4, 8, 16, and 28 weeks and the NC group at 16 and 28 weeks were compared. Resultantly, we found that with the increase in time, the gluconolactone is gradually increasing in the model group, and a lower level of gluconolactone in the NC group at 16 and 28 weeks was observed (

Figure 5A). The increasing gluconolactone could be from glucose oxidation by glucose oxidase and lead to produces FADH2 from FAD (Wong et al., 2008). In a previous analysis, we found that gluconolactone and gluconic acid were associated with AS index, IMT, endothelial injury, and inflammation (

Figure 3B). Especially, a higher significantly positive correlation between gluconolactone and AS index (R = 0.74, p= 8.4e-05) (Figure S1) and a higher significantly positive correlation between gluconolactone and vascular injury marker vWF (R = 0.9, p <2.2e-6) were observed (

Figure 5B), respectively. It implied that gluconolactone is associated with vascular injury and AS. Increasing evidence showed that gluconolactone is associated with the dysfunction of cardiovascular disease (Cao et al., 2023). The gluconolactone and gluconic acid were part of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). However, the other metabolites such as glucose, 6-phosphogluconic acid, D-ribose, and ribose 1,5-bisphosphate in the PPP were not correlated with AS index (Figures 5C and S1). Taken together, gradually enriched gluconolactone could play a critical role in the development of AS.

3.5. Biopterin was reduced in the late stage of AS

For the metabolites which were reduced in the model group in cluster 4, using the same comparing method above, we found some metabolites such as biopterin, L-Homophenylalanine, and Tranylcypromine were gradually decreased in the development of AS from 4 weeks to 28 weeks in the model group and kept a higher level in the NC group at 16 and 28 weeks (Figures 5D and S2).

Biopterin is an oxidative product of BH4 which could reduce coronary artery disease and improve endothelial function by decreasing nitric oxide (NO) production (Willibald et al., 2000). The negative correlations between AS index and biopterin (R = -0.63, p = 0.013) were observed (

Figure 5E and Figure S3). Apart from that, biopterin negatively correlated with EF-1 (R = -0.63, p = 0.037) (Figure S3). It implied that biopterin plays an important role in vascular injury and AS.

4. Discussion

Tibetan minipig is a characteristic breed in China, which has been widely used in the research of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Our previous studies showed that Tibetan minipigs are susceptible to the formation of AS lesions in high-fat diets, and obvious lipid disorders and inflammatory reactions can be observed (Yang et al., 2022). Tibetan minipigs as an AS model animal for studying the pathogenesis of human AS have a clear advantage. Using the AS model of Tibetan minipigs, it is helpful to explain the metabolic mechanism of AS induced by high fat and cholesterol diet from the perspective of metabolomics. However, the pathological characteristics and mechanism of the Tibetan minipigs AS model have not been fully clarified. In this study, we built an AS animal model using Tibetan minipigs fed with the high-fat and high-cholesterol diet for identifying the changes of serum metabolites at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 28 weeks and finding related metabolic pathways. Based on the untargeted metabolome, the differential abundance of metabolites in the development of AS. We found that the sphingolipid metabolism and glucose oxidation were enriched in the AS group and the phenylalanine metabolism was reduced in the AS group.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease with a complex pathological mechanism that involves the imbalance of lipid metabolism, oxidative stress response, and the inflammatory response of vascular endothelial cells. Vascular endothelial injury plays a critical role in AS occurrence and development (Wang et al., 2021). In the development of AS, reducing biopterin is significantly associated with the aggravation of endothelial injury. It has been reported that Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a biopterin reduction product, can reduce coronary artery disease and improve endothelial function by decreasing nitric oxide (NO) production (Willibald et al., 2000). It further proves that biopterin plays a key role in the development of AS. In the development of AS, gluconolactone is higher significantly positively correlated with endothelial injury factor vWF. During endothelial injury, stress oxidation occurs in the body, and more glucose is oxidized, which leads to the accumulation of gluconolactone. The increasing gluconolactone could indicate the redox state in the body which is associated with a series of physiological and metabolic effects for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In the development of AS, gluconolactone was enriched in the late stage of AS whereas biopterin was enriched in the early stage of AS. Gluconolactone and biopterin could be potential biomarkers for indicating the development of AS. However, these potential biomarkers needed further confirmation in a larger human cohort.

Author Contributions

Chen Minli is responsible for project administration and funding acquisition. Shen Liye is responsible for conducting experiments, analyzing data, and writing the manuscript. Wang Jinlong is responsible for analyzing data, and writing the manuscript. All the authors are responsible for revising the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the national natural science foundation of China (31970514).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Competing interests: All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This project has been approved by the Ethics Committee.

Consent for publicatio: All authors of this article agreed to be published.

References

- Acosta, S., Johansson, A., and Drake, I. (2021). Diet and Lifestyle Factors and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease-A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 13. [CrossRef]

- Becht, E., McInnes, L., Healy, J., Dutertre, C.A., Kwok, I.W.H., Ng, L.G., Ginhoux, F., and Newell, E.W. (2018). Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Liu, Z., Ma, W., Fang, C., Pei, Y., Jing, Y., Huang, J., Han, X., and Xiao, W. (2023). Untargeted metabolomic profiling of sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14, 1060470. [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, C., Obinata, H., Kumaraswamy, S.B., Galvani, S., Ahnström, J., Sevvana, M., Egerer-Sieber, C., Muller, Y.A., Hla, T., Nielsen, L.B., et al. (2011). Endothelium-protective sphingosine-1-phosphate provided by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 9613-9618. [CrossRef]

- Dias, P., Pourova, J., Voprsalova, M., Nejmanova, I., and Mladenka, P. (2022). 3-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid: A Blood Pressure-Reducing Flavonoid Metabolite. Nutrients 14. [CrossRef]

- Iida, M., Harada, S., and Takebayashi, T. (2019). Application of Metabolomics to Epidemiological Studies of Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis 26, 747-757. [CrossRef]

- Kattoor, A.J. Kattoor, A.J., Pothineni, N.V.K., Palagiri, D., and Mehta, J.L. (2017). Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Current atherosclerosis reports 19, 42. [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, T.T., Nuotio, J., Rovio, S.P., Niinikoski, H., Juonala, M., Magnussen, C.G., Jokinen, E., Lagström, H., Jula, A., Viikari, J.S.A., et al. (2020). Dietary Fats and Atherosclerosis From Childhood to Adulthood. Pediatrics 145. [CrossRef]

- Lecce, L., Xu, Y., V'Gangula, B., Chandel, N., Pothula, V., Caudrillier, A., Santini, M.P., d'Escamard, V., Ceholski, D.K., Gorski, P.A., et al. (2021). Histone deacetylase 9 promotes endothelial-mesenchymal transition and an unfavorable atherosclerotic plaque phenotype. J Clin Invest 131. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Zhou, G., Ewald, J., Chang, L., Hacariz, O., Basu, N., and Xia, J. (2022). Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 for LC-HRMS spectra processing, multi-omics integration and covariate adjustment of global metabolomics data. Nat Protoc 17, 1735-1761. [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A., Mensah, G.A., and Fuster, V. (2020). The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks: A Compass for Global Action. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 76, 2980-2981. [CrossRef]

- Schissel, S.L., Tweedie-Hardman, J., Rapp, J.H., Graham, G., Williams, K.J., and Tabas, I. (1996). Rabbit aorta and human atherosclerotic lesions hydrolyze the sphingomyelin of retained low-density lipoprotein. Proposed role for arterial-wall sphingomyelinase in subendothelial retention and aggregation of atherogenic lipoproteins. J Clin Invest 98, 1455-1464. [CrossRef]

- Shim, J., Al-Mashhadi, R.H., Sørensen, C.B., and Bentzon, J.F. (2016). Large animal models of atherosclerosis--new tools for persistent problems in cardiovascular medicine. The Journal of pathology 238, 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Skoura, A., Michaud, J., Im, D.S., Thangada, S., Xiong, Y., Smith, J.D., and Hla, T. (2011). Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-2 function in myeloid cells regulates vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31, 81-85. [CrossRef]

- Stamilio, D.M., and Scifres, C.M. (2014). Extreme obesity and postcesarean maternal complications. Obstetrics and gynecology 124, 227-232. [CrossRef]

- Toyama, H., Furuya, N., Saichana, I., Ano, Y., Adachi, O., and Matsushita, K. (2007). Membrane-bound, 2-keto-D-gluconate-yielding D-gluconate dehydrogenase from "Gluconobacter dioxyacetonicus" IFO 3271: molecular properties and gene disruption. Applied and environmental microbiology 73, 6551-6556. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Wang, M., Ye, J., Sun, G., and Sun, X. (2021). Mechanism overview and target mining of atherosclerosis: Endothelial cell injury in atherosclerosis is regulated by glycolysis. International journal of molecular medicine 47, 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Liu, R., Zhu, W., Chu, H., Yu, H., Wei, P., Wu, X., Zhu, H., Gao, H., Liang, J., et al. (2019). UDP-glucose

accelerates SNAI1 mRNA decay and impairs lung cancer metastasis. Nature 571, 127-131. [CrossRef]

- Willibald, M., Cosentino, F., Lütolf, R.B., Fleisch, M., Seiler, C., Hess, O.M., Meier, B., and Lüscher, T.F. (2000). Tetrahydrobiopterin Improves Endothelial Function in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 35, 173-178. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.M., Wong, K.H., and Chen, X.D. (2008). Glucose oxidase: natural occurrence, function, properties and industrial applications. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 78, 927-938. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Kamato, D., Little, P.J., Nakagawa, S., Pelisek, J., and Jin, Z.G. (2019). Targeting epigenetics and non-coding RNAs in atherosclerosis: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther 196, 15-43. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Pelisek, J., and Jin, Z.G. (2018). Atherosclerosis Is an Epigenetic Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 29, 739-742. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Xu, Y., Shen, L., Pan, Y., Huang, J., Ma, Q., Yu, C., Chen, J., Chen, Y., and Chen, M. (2022). Guanxinning Tablet Attenuates Coronary Atherosclerosis via Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Tibetan Minipigs Induced by a High-Fat Diet. J Immunol Res 2022, 7128230. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., Liu, J., Wang, M., Zhang, X., and Zhou, M. (2019). Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nature reviews Cardiology 16, 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Xian, X., Wang, Z., Bi, Y., Chen, Q., Han, X., Tang, D., and Chen, R. (2018). Research Progress on the Relationship between Atherosclerosis and Inflammation. Biomolecules 8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).