1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 virus was first identified in Brazil in February 2020, and thereafter disseminated throughout the large metropolitan areas of the state capitals. São Paulo in the southeast was the main disseminator of SARS-CoV-2 during the first three weeks of the epidemic. Shortly thereafter, 16 other cities contributed to the dissemination of cases across the country [

1]. The virus spread further to the interior of the country. By March 22, 2020, 25 days after the first confirmed case, all states had reported cases [

2].

In Ceará State in northeast Brazil, the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed on March 15, 2020 [

3]. One month later, the state capital Fortaleza and its metropolitan region had high detection rates. Other regions in the hinterland were also registering high detection rates, confirming the ruralization of the disease in the state [

4]. By April 2020, 57% of the 184 municipalities in Ceará had confirmed cases. Until May 2023, a total of 1,470,075 cases of COVID-19 and 28,179 deaths were confirmed in Ceará, a case fatality rate of 1.9% [

5]. In the same period, Brazil recorded more than 37 million cases and 700,000 deaths [

6].

During the first epidemic waves, the federal government had not performed coherent responses to confront COVID-19 at the national level, leaving the states, Federal District, and municipalities with their decision-making to implement social distancing and other measures [

7]. The COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Brazil began only in January 2021, initially contemplating priority groups. Despite the delay and little support from the federal government, a total of 513,470,835 vaccine doses were applied until May 2023, due to the efforts of the state governments, and the Unified Health System (SUS) [

7,

8,

9]. Ceará started vaccination against COVID-19 in January 2021, and by May 2023 reached a dose 2 vaccination coverage in the general population of 90.1% [

6]. A study in Ceará showed a massive reduction in COVID-19-related deaths >75 years of age, in the SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated population [

10].

Since the registration of the first cases of COVID-19, the municipality of Itapajé, in the interior of the state, developed control measures. Despite all efforts, the virus spread in the municipality, causing a collapse of health services. Here we describe the temporal and spatial evolution of the epidemic in this small municipality, starting from the index case of COVID-19, and describe control measures adopted by the local government, and their effects on morbidity and mortality patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area

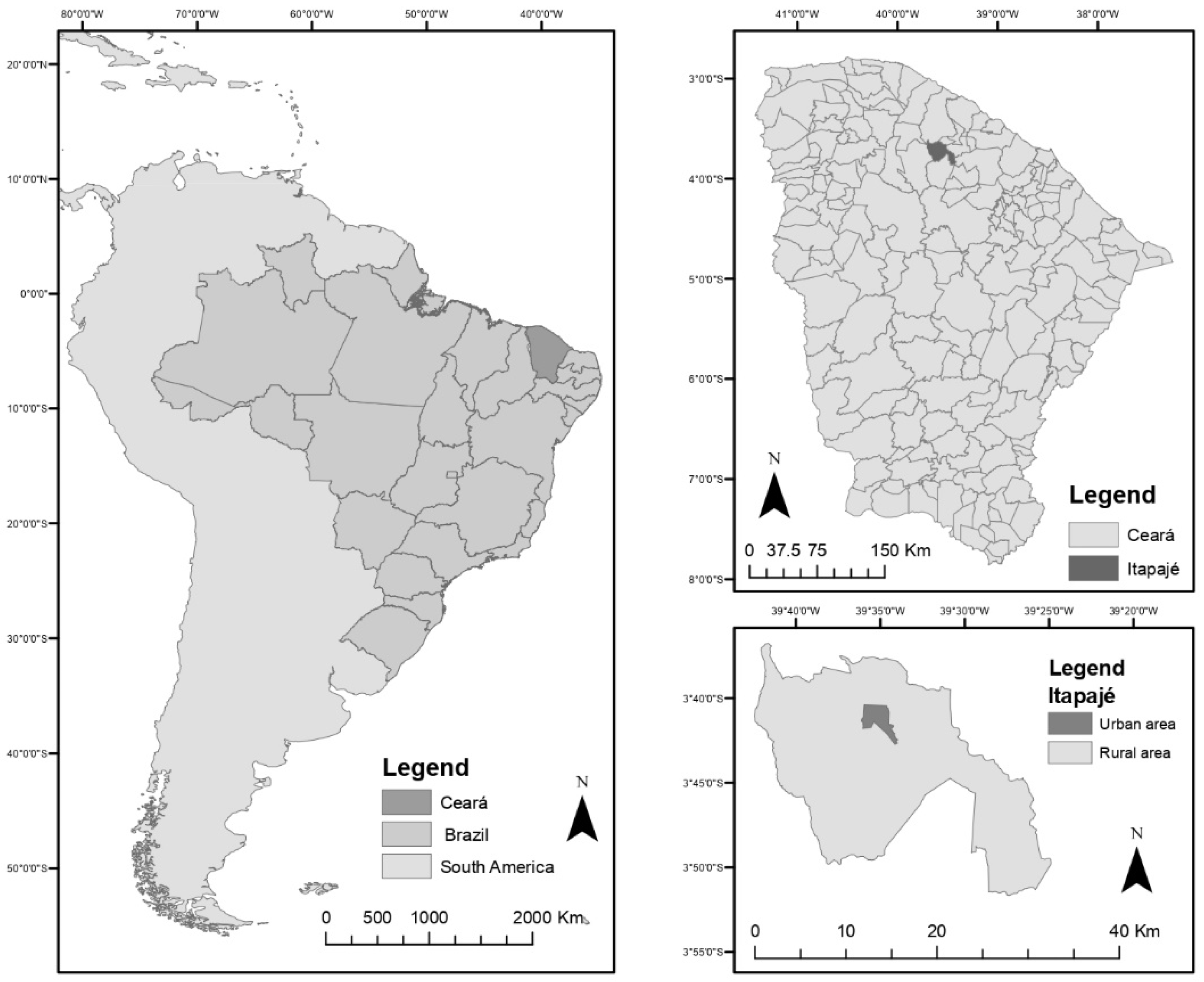

The municipality of Itapajé is located in the northern region of the state of Ceará, 123 km from the state capital Fortaleza (

Figure 1). It has an extension of 431 km², and is characterized by semi-arid tropical hot climate, with average rainfall of 858 mm and average annual temperatures ranging between 26 °C and 28 °C.

The estimated population in 2021 was 53,448 inhabitants, with an urbanization rate of 70.3% and a population density of 110 inhabitants/km2.

2.2. Study population and period

The study population was composed of the 3,020 confirmed COVID-19 cases, registered from April 02, 2020, the date of confirmation of the first case of COVID-19 in the municipality, until December 31, 2021. We included notifications of confirmed cases residing in the municipality, and excluded duplicate entries, and notifications of non-residents.

2.3. Variables and data sources

Data on date of symptom onset, address, case evolution, and date of death were obtained from the local database of the Itapajé Municipal Health Department of the e-SUS Notifica and the Influenza Epidemiological Surveillance Information System (SIVEP-Gripe). E-SUS Notifica is an online system created by the Federal SUS Department of Informatics (DATASUS) registering notifications of suspected and confirmed cases of mild influenza syndrome from COVID-19. The notifications of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) hospitalized in the public and private networks, and the notification of deaths from COVID-19 regardless of hospitalization are registered in SIVEP-Gripe [

11].

Other sources of information included the investigation report of the first case of SARS-CoV-2 detected in Itapajé, Municipal Plan for Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic, report of Sanitary Surveillance inspections and municipal decrees. Demographic data for the municipality were obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

2.4. Data processing and analysis

Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA, USA) was used for data organization and storage, in addition to the elaboration of epidemiological curves, figures and tables, and to calculate the indicators.

The characterization of the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was carried out in a narrative way, based on the municipal epidemiological surveillance report. Additional information was obtained from municipal decrees and the Municipal Plan for coping with the pandemic of COVID-19 for the narrative description of the control measures implemented in the municipality.

In the epidemiologic curve, the confirmed cases of COVID-19 were presented by epidemiologic week (EW) according to the date of onset of symptoms. The epidemic curve of deaths was presented by date of occurrence of death.

From the absolute number of confirmed cases and deaths by COVID-19, we calculated incidence (number of confirmed cases divided by the resident population, multiplied by 100,000 inhabitants), mortality (number of deaths by COVID-19 divided by the resident population, multiplied by 100,000 inhabitants) and case fatality rates (number of deaths by COVID-19 divided by the total of confirmed cases, multiplied by 100).

Spatial analysis was performed using the Terraview 4.2.2 program (INPE - National Institute for Space Research—

http://www.dpi.inpe.br/terralib5/wiki/doku.php?id=wiki:downloads:terraview_terralib_4.2.2). We used the maps of geographic location (latitude and longitude) of the cases and deaths in each of the epidemic waves. In addition to these maps we used a map of census sectors of the urban area of the municipality of Itapajé with the information of the resident population in each of these sectors in the year 2022.

The maps of cases and deaths were obtained by locating the address of each case and death in the urban area of the city, using the program Google Earth. Each address was geographically located in .kml format and then converted to .shp format, and adjusted to Polychonic/SIRGAS 2000 projection.

For the kernel density maps, the following parameters were used: for the support region the option grid over region was selected, in the grid options 1000 columns were used and having as base the map of the census sectors of the urban area of the city, the data sets were the maps of cases and deaths of each one of the epidemic waves, analyzed separately, but in both the algorithm used was with the quadratic function for the calculation of density and with adaptive radius.

For the calculation of the kernel ratio, the support region was gridless, the first data set was composed of the maps of cases and deaths of each of the waves and the second data set was the map of the census sectors, the latter had as attribute the population of each sector. Similarly, to the kernel density analysis, the algorithm used was with the quadratic function for the calculation of the density and adaptive radius.

2.4. Ethical Aspects

Data were extracted from secondary databases. The use of data was authorized by the Municipal Health Secretariat of Itapajé. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) under CAAE 51850221.8.0000.5054.

3. Results

3.1. Index Case

The first diagnosed case of COVID-19 in Itapajé was a 61-year-old housewife. She had traveled to São Paulo to visit relatives on March 1, 2020, where she stayed until March 17, 2020. On March 18, 2020, she returned to Itapajé. She sought medical assistance at the local hospital on March 20, 2020 with complaints of sore throat, dry cough, running nose, fever, and dyspnea. She reported onset of signs/symptoms on March 14, 2020. The patient was immediately treated and reported as a suspected case of COVID-19, and was referred to the state reference hospital for infectious diseases in Fortaleza, the state capital. There, she received medical care and a naso-oropharyngeal swab was collected for real-time RT-PCR examination, with confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 on April 2, 2020. She progressed to complete cure.

3.2. Epidemic

Since the confirmation of the first allochthonous case in Itapajé, 3,020 cases have been registered until December 31, 2021. Of these, 135 (4,5%) progressed to death. The cumulative incidence and mortality rates were 5,650.3 cases and 252.6 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively.

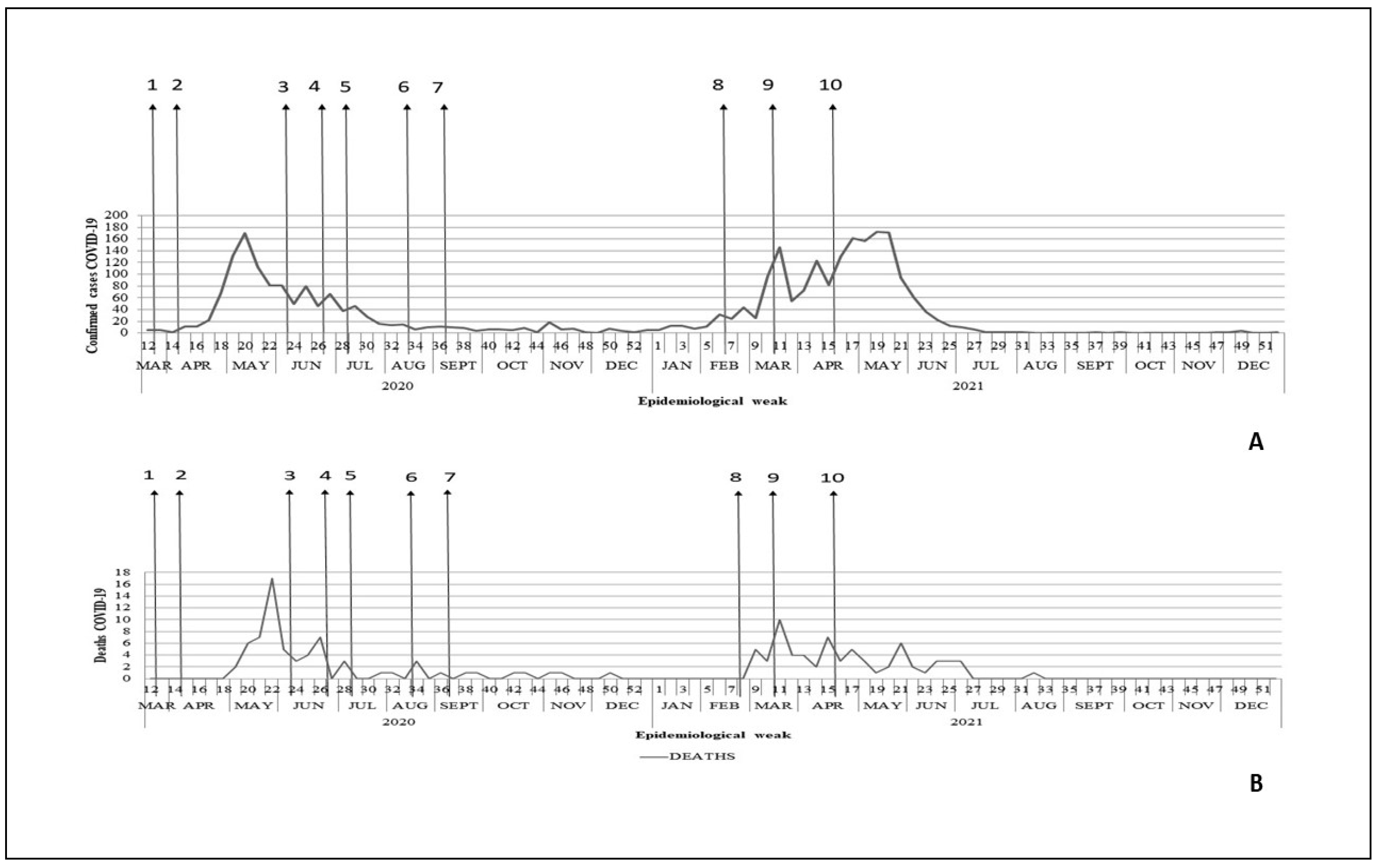

The first autochthonous cases of COVID-19 in Itapajé occurred in mid-March 2020, with a significant increase in late April and early May, and a peak of cases of the first wave of transmission in May 2020 (170 cases) (

Figure 2). This was followed by a reduction from June and stabilization of the number of cases at low levels until December 2020 (

Figure 2). The second epidemic peaked in May of 2021 (172 cases). This was followed by a period of reduction that extended until June, when transmission dropped to very low levels.

The first deaths from COVID-19 occurred in May 2020, 80 days after the first cases. The peak number of deaths occurred in May, followed by a reduction. During the second wave, deaths were recorded in the months of February to early July, with a peak in March (

Figure 2).

The first epidemic wave resulted in incidence and mortality rates of 2,302.7 cases and 126.3 deaths, per 100,000 population, respectively. The case fatality in the period was 5.5%. The second wave, which began by the end of December 2020, had an incidence of 3,364.0 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, a mortality of 127.2 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, and a case fatality of 3.8%.

3.3. Spatial distribution

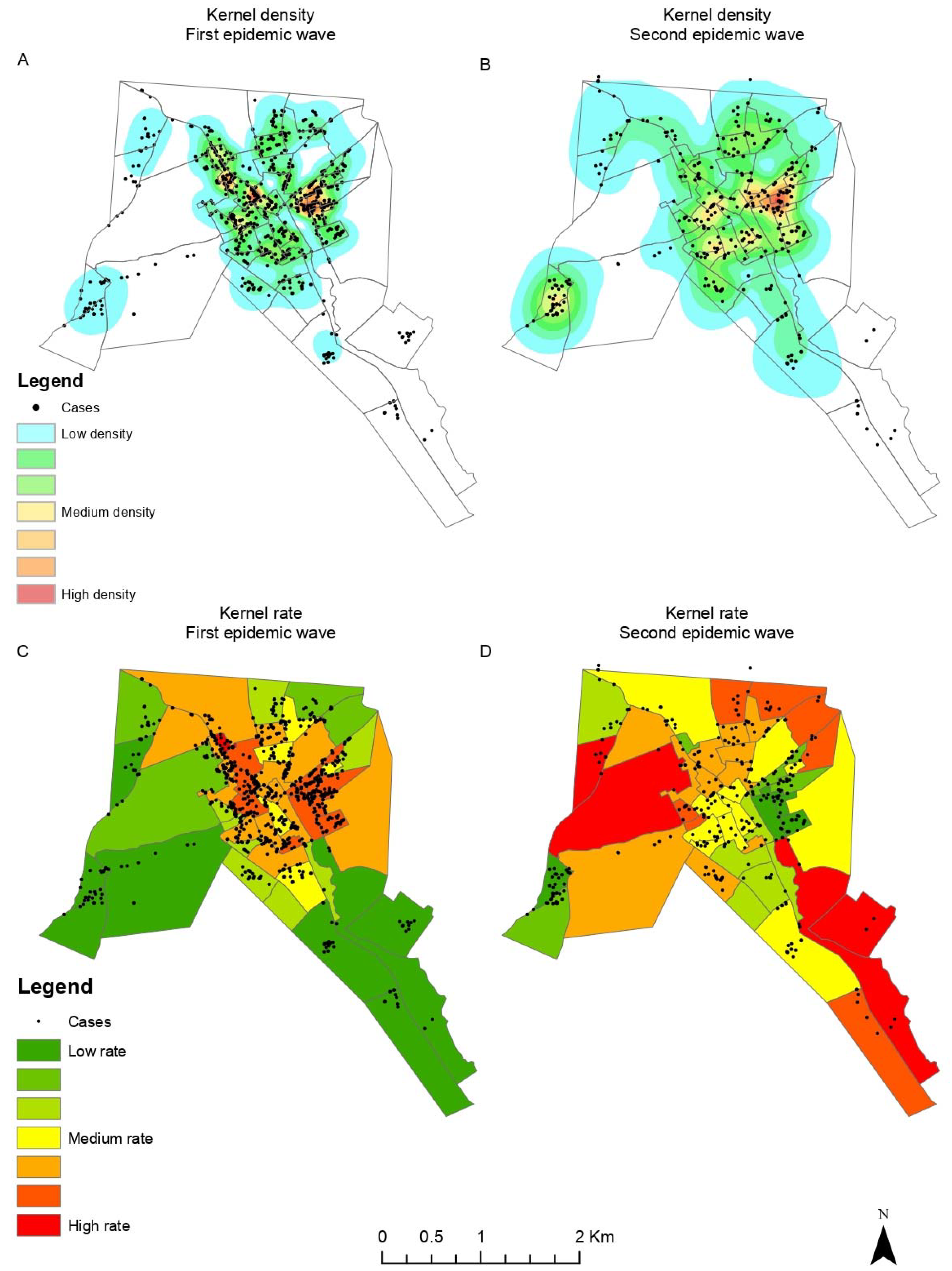

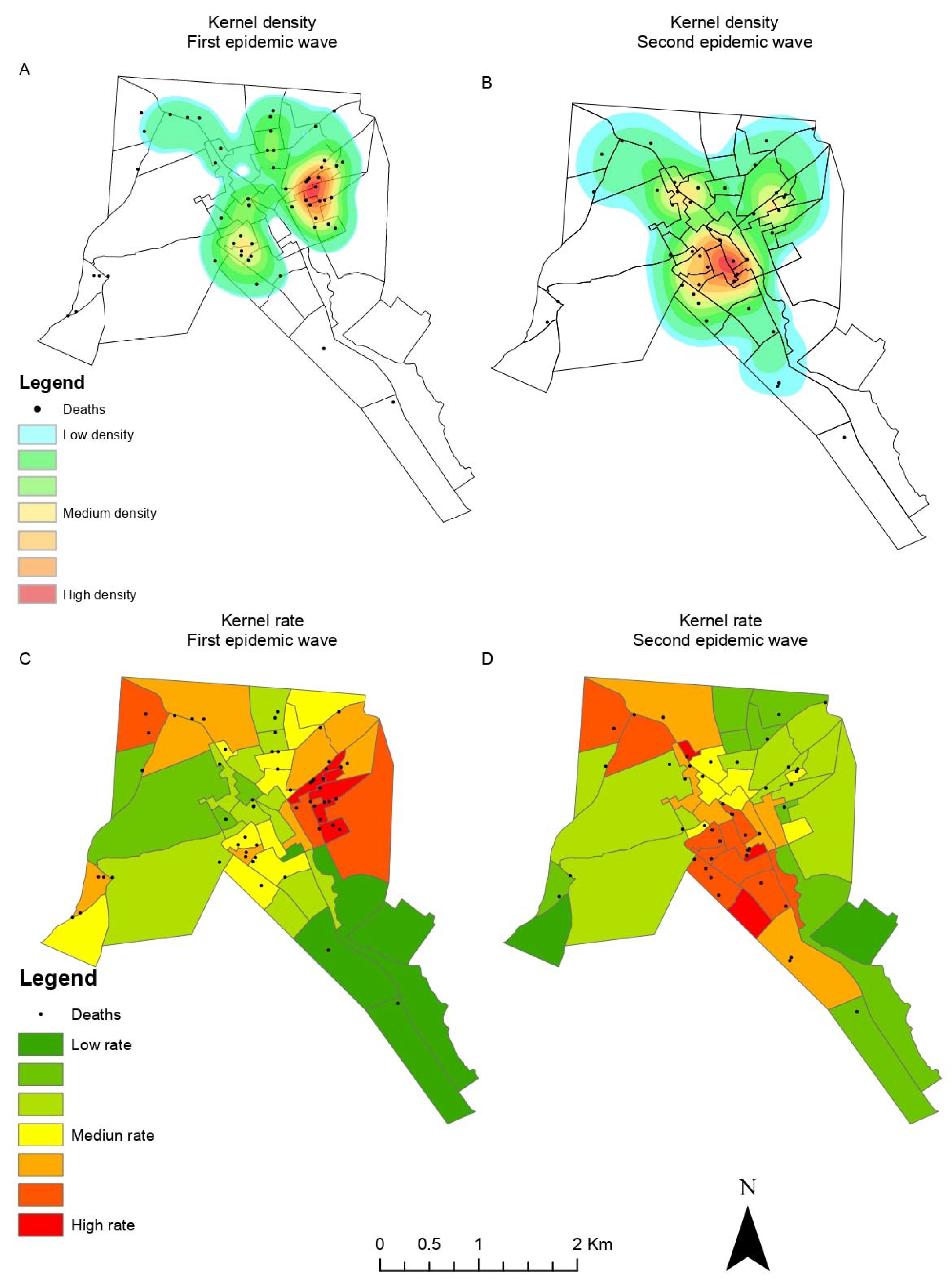

A total of 2,691 confirmed COVID-19 cases were geographically located and mapped, including 132 deaths. The kernel density analysis revealed higher intensities of cases and deaths by COVID-19 located in the city center of Itapajé (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

In the beginning of the epidemic (first wave), cases were concentrated in the central area of the city, with a subsequent expansion to the peripheral neighborhoods during the second wave (

Figure 3). A similar pattern could be observed for high risk clusters for death (

Figure 4).

3.4. Control Measures

The municipality published 69 decrees that dealt with restriction measures, surveillance, and maintenance of social isolation, to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The first decree, published on March 17, 2020, announced a state of health emergency in the municipality, and established restrictive measures: suspension of any public or private events, activities in public schools, gyms, concert halls, municipal stadiums, and commercial establishments with more than 30 people, and collective activities and events in temples and churches. Then, through another decree from April 1, 2020, the municipality intensified the restriction measures by closing non-essential businesses and industries. On May 6, 2020, the obligatory use of industrial or household face masks was established throughout the municipal territory. As of May 31, 2020 the restrictive measures were gradually loosened.

With the advent of the second epidemic wave, on February 15, 2021, the state of public emergency was extended in the municipality. Later, on February 18, 2021, measures were announced: suspending classes and classroom activities in educational establishments; restricting opening hours of businesses and services; prohibiting the use of public spaces from 5:00 PM to 5:00 AM; adopting a remote work regime for the municipal civil service with the exception of essential services; and instituting a "curfew”. On March 13, 2021, strict social isolation was instituted with the establishment of a special duty of confinement, control of vehicle circulation, prohibition of the circulation of people in public spaces and on public roads, prohibition of face-to-face religious celebrations, and closure of non-essential businesses. The rigid lockdown began to be gradually relaxed on April 11, 2021 (

Figure 2).

Vaccination against COVID-19 began in the municipality on January 20, 2021 with the priority public of health professionals who worked in the front line and those aged 75 years or older. In March, vaccinations were extended for those aged 65 to 74 years, in April for 60 to 64 years-olds, and in June for the population with comorbidities in descending order of age and public and private school teachers. Thereafter the vaccination campaign continued with the population aged 5 to 59 years (general population), obeying the priority according to the decreasing order of the age groups. In the year 2021, the vaccination coverage reached 40.63%.

4. Discussion

Our study described the epidemic features, control measures and spatial distribution of SARS-CoV-2 in a small municipality in rural Northeast Brazil. The city of Itapajé borders a federal highway of intense flow of people and goods that connects Fortaleza to cities in the interior of the state and to the states Piauí, Maranhão and Pará. Itapajé is a commercial center for the small neighboring towns for commerce and services. This mobility has possibly contributed to the introduction and maintenance of SARS-CoV-2. Studies have reported that the highest incidences by COVID-19 in general occurred in urban metropolitan regions, being related to higher population, higher population density, and high urban mobility [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Itapajé had a lower incidence per 100,000 inhabitants of COVID-19 than those obtained in Brazil (10,636.7), Ceará State (10,527.0) and the state capital Fortaleza (10,376.2) [

7]. On the other hand, the health system did not have adequate physical infrastructure and human resources to deal with the ongoing epidemic. There was only a secondary level hospital with a capacity of 30 beds. The mortality rate was higher as compared to Brazil (292.4) and Ceará (270.0), presenting similar values in the first and second waves of infection [

6]. Similarly, the case fatality in Itapajé was higher than in Ceará (2.6), and the state capital Fortaleza (4.0) [

6] The scarcity in health services support, especially the availability of intensive care unit (ICU) beds associated with the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 contributed to the higher mortality and case fatality rates by COVID-19 in smaller municipalities [

16].

The spatial analysis showed that the highest density of cases of COVID-19 occurred in downtown Itapajé, where there is a greater flow of workers and people seeking commerce and services, which enabled viral transmission [

17]. Mobility restrictions may have slowed the process of SARS-CoV-2 spread, but they could not change the routes of the expansion of the virus [

18].

The epidemiological curve of COVID-19 showed a pattern similar to that observed in the state of Ceará and in the capital Fortaleza [

19,

20]. In both the first and the second waves, the peaks of cases and deaths in the capital preceded by a few weeks those observed in Itapajé and in the interior of the state of Ceará. In fact, evidence suggests that all northeastern Brazilian states share the same epidemiological characteristics of increase of cases and deaths, extending from capital cities to the inland municipalities [

21]. Our findings confirm previous studies from the state capital Fortaleza – a major metropolitan city – where the epidemic started in higher income neighborhoods and then spread to the more socially vulnerable peripheral neighborhoods [

22,

23]. In most vulnerable neighborhoods, there are deficient urban infrastructure, high unemployment rates, difficult of access to basic health services and lack of household structure, making it difficult to adopt measures to control the disease [

24]. Similarly, higher risks of deaths from COVID-19 have been reported in resource-poor areas, and in regions with high population density, urban mobility and deficienct health services [

25]. However, the higher income neighborhoods also showed high rates of deaths in the second wave, which may be related to non-adherence to vaccination and control measures.

The lack of leadership from the federal government in formulating a national response to mitigate and suppress COVID-19 led the Federal Supreme Court (STF) to assign to the states, federal district, and municipalities the competence to coordinate responses in their territories. Thus, the Government of the State of Ceará took over the coordination of these measures in the state, guiding the municipalities in prevention and control. The first social distancing measures to combat the spread of SARS-CoV-2 were implemented in Itapajé before the notification of the first case in the municipality [

26].

Social vulnerability, informal work, unemployment, and extreme poverty were factors that probably interfered with adherence to control measures.21 People with informal work, such as market vendors, were forced to go out daily in search of income, exposing themselves to infection. Thus, the challenge in implementing social distancing measures was to maximize the desired effects on health and minimize the inevitable economic and social damages [

27]. This required ensuring policies of social protection, minimum income, and labor protection. Consequently, state and municipal governments exempted the most vulnerable population groups from electricity and water bills, and distributed food baskets [

28]. At the national level, the National Congress approved the Emergency Aid to ensure minimum income to the vulnerable population and guarantee the social distancing measures. However, a large part of the population needed to crowd in long lines at the local bank or lottery to receive the benefits. This situation was observed also in Itapaje and, considering that the city is the hub for banking services to small neighboring towns, the increase in local mobility may have impacted the spread of the epidemic.

Another relevant factor was the denial of the serious health situation by some groups and the consequent noncompliance with the measures of social distancing. The denialist posture of the federal government did not contribute to the efforts of state and municipal managers for mitigation of the epidemic [

29].

The relaxation of social distancing measures in Itapajé in the first wave occurred when the epidemiological curve showed inconsistent decrease in the number of cases and critical moment regarding the number of deaths. In fact, the moment of relaxation of social distancing measures in the northeastern capitals occurred prematurely. Despite the limitations of the measures adopted by states and municipalities in the Northeast, there is evidence that the effects of the pandemic were mitigated [

15,

30], with the epidemiological scenario of COVID-19 included directly by the control measures adopted throughout the pandemic [31].

The economic opening and the municipal elections that took place in November 2020 influenced the beginning of the explosive growth of cases of the second wave of COVID-19 in northeastern Brazil [

21]. In Itapajé the municipal elections and the change of management caused a discontinuity in the epidemiological monitoring and the actions to contain the epidemic, due to the relaxation of control measures in the pre-electoral period.

In Brazil there was a delay in the acquisition of vaccines against COVID-19 and the campaign started only in January 2021. The number of doses were initially insufficient to cover the entire population, requiring the initial prioritization of population groups at higher risk and subsequent expansion to the population as more doses of vaccine were acquired. The vaccination campaign in Itapajé progressed slowly, and the adherence of a considerable part of the population to the vaccine was low. The local health system outlined several strategies such as task forces, drive through, active search in homes, industries and public agencies, achieving vaccination coverage by May 2023 of 72.2% of first dose and second/single dose of 70% [

5]. Despite all these difficulties, the Unified Health System (SUS) managed to make the vaccine reach the entire Brazilian territory, achieving the success of the vaccination campaign, contributing to reducing the occurrence and transmission of the disease; and the number of deaths [

7,

10]. SUS played a pivotal role in the planning, coordination, and execution of all the mitigation measures to the epidemic of COVID-19 at the municipal level. SUS guarantees the promotion, protection, and recovery of health to the Brazilian population guided by the principles of universalization, equity, and integrality.

Limitations of our study include the underreporting of cases and deaths at the beginning of the pandemic, due to the scarcity of tests and reagents that led to the recommendation to test only patients older than 60 years, people with comorbidities and with severe condition admitted to hospital units. During the second wave, the expansion of diagnostic tests allowed a better quality of the official data from the Epidemiological Surveillance, enabling an approximation of the size of the epidemic at the local level, and may be related to the higher incidence per 100,000 inhabitants of COVID-19 recorded in this wave of infection in Itapajé.