Submitted:

05 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population and Ethics

2.2. Questionnaires and Measurements

- -

- Part-A finalized to acquire items in maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes (maternal age, ethnicity, country of birth, education level, working status, smoking status, medical and obstetric history, perinatal outcomes). Data reported by patients were confirmed by reviewing electronic medical records.

- -

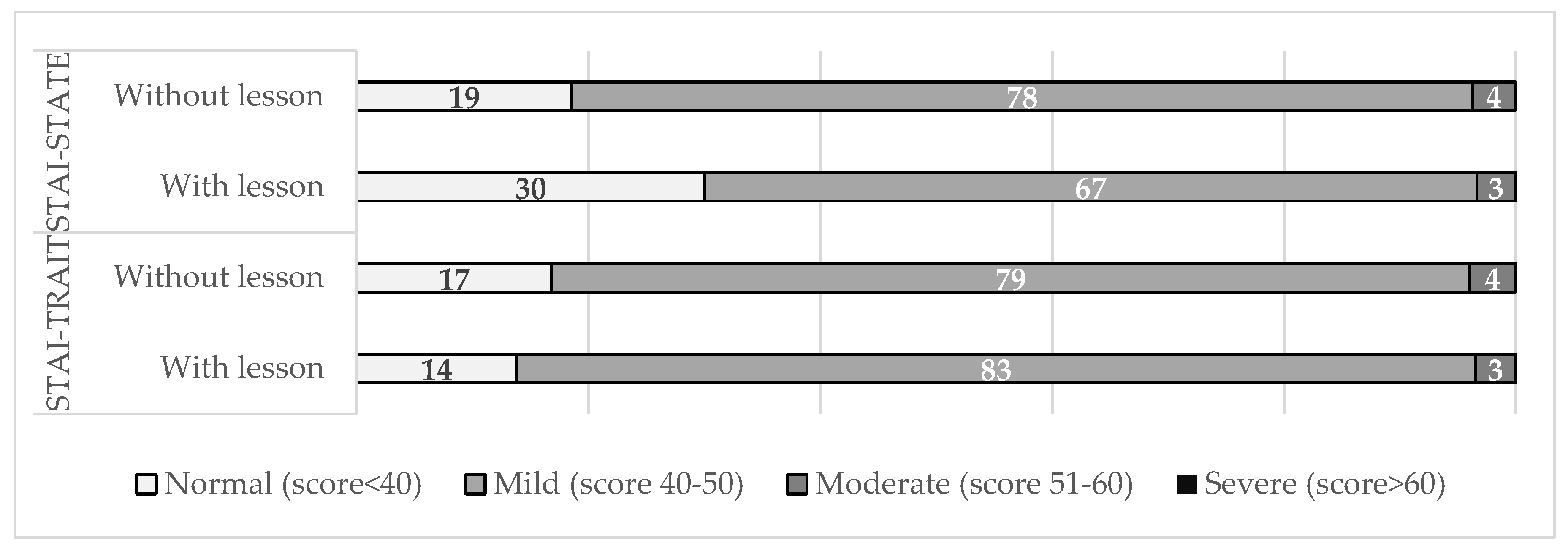

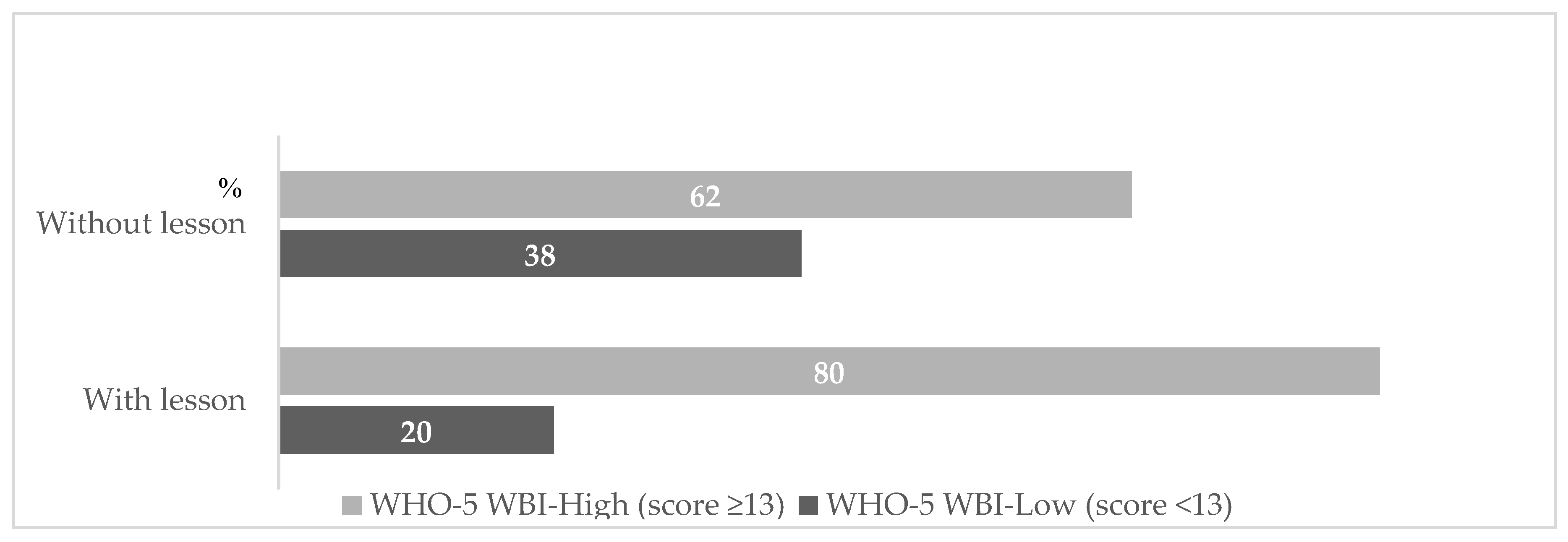

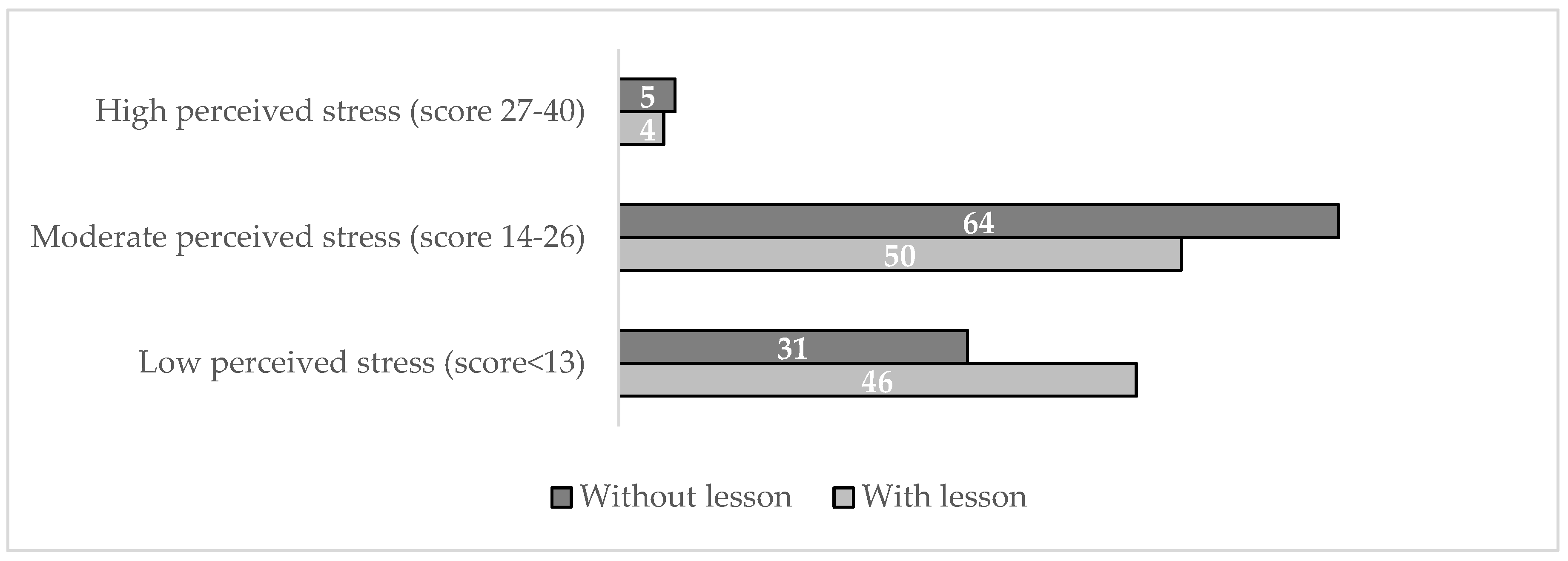

- Part-B finalized to assess the impact of prenatal educational on vaccine measured by using validated questionnaires (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, STAI; Perceived Stress Scale, PSS; World Health Organization- Five Well-Being Index, WHO-5) addressed to the patients. All tests were administrated in Italian translation.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Clinical Implications and Future Challenges

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- https://www.who.int/news/item/18-08-2015-vaccine-hesitancy-a-growing-challenge-for-immunization-programmes.

- https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.

- Scendoni, R.; Fedeli, P.; Cingolani, M. The State of Play on COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: Recommendations, Legal Protection, Ethical Issues and Controversies in Italy. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brabandere, L.; Hendrickx, G.; Poels, K.; Daelemans, W.; Van Damme, P.; Maertens, K. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and social media on the behaviour of pregnant and lactating women towards vaccination: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2023, 13, e066367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgui, J.; Atallah, A.; Boucoiran, I.; Gomez, Y.H.; Bérard A; the CONCEPTION Study Group. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake and reasons for hesitancy among Canadian pregnant people: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2022, 10, E1034–E1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantaki, A.; Kalogeropoulou, V.E.; Taskou, C.; Nanou, C.; Lykeridou, A. COVID-19 Vaccination and Related Determinants of Hesitancy among Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Cos, A.; Marbán-Castro, E.; Nedic, I.; Ferrari, M.; Crespo-Mirasol, E.; Ventura, L.F.; Zamora, B.N.; Fumadó, V.; Menéndez, C.; Martínez Bueno, C.; Llupià, A.; López, M.; Goncé, A.; Bardají, A. “Maternal Vaccination Greatly Depends on Your Trust in the Healthcare System”: A Qualitative Study on the Acceptability of Maternal Vaccines among Pregnant Women and Healthcare Workers in Barcelona, Spain. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.worldometers.

- Vilca, L.M.; Cesari, E.; Tura, A.M. Barriers and facilitators regarding influenza and pertussis maternal vaccination uptake: a multi-center survey of pregnant women in Italy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020, 247, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurici, M.; Dugo, V.; Zaratti, L.; et al. Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women toward flu vaccination: a cross-sectional survey. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 3147–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussink-Voorend, D.; Hautvast, J.L.; Vandeberg, L.; Visser, O.; Hulscher, M.E. A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.J.; Paterson, P.; Jarrett, C.; Larson, H.J. Understanding factors influencing vaccination acceptance during pregnancy globally: A literature review. Vaccine 2015, 33, 6420–6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricola, E.; Gesualdo, F.; Alimenti, L. Knowledge attitude and practice toward pertussis vaccination during pregnancy among pregnant and postpartum Italian women. Hum Vacc Immunother 2016, 12, 1982–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.L. Predictors of maternal vaccination in the United States: An integrative review of the literature. Vaccine 2016, 34, 3942–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Napolitano, F.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Angelillo, I.F. Vaccination knowledge and acceptability among pregnant women in Italy. Hum Vacc Immunother 2018, 14, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poliquin, V.; Greyson, D.; Castillo, E. A systematic review of barriers to vaccination during pregnancy in the Canadian context. JOGC 2019, 41, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scatigna, M.; Appetiti, A.; Pasanisi, M.; D’Eugenio, S.; Fabiani, L.; Giuliani, A.R. Experience and attitudes on vaccinations recommended during pregnancy: survey on an Italian sample of women and consultant gynecologists. Hum Vacc Immunother 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.epicentro.iss.

- DeSisto, C.L.; Wallace, B.; Simeone, R.M. Risk for stillbirth among women with and without COVID-19 at delivery hospitalization — United States, March 2020–September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.G.; Terreri, S.; Terrin, G. SARS-CoV-2 infection versus vaccination in pregnancy: Implications for maternal and infant immunity. Clin Infect Dis Published online 2022.

- Tanne, J.H. Covid-19: Vaccination during pregnancy is safe, finds large US study. Brit Med J 2022, 7, o27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Salvatori, G.; Dotta, A.; Auriti, C. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines during pregnancy and breastfeeding: a systematic review of maternal and neonatal outcomes. Viruses 2022, 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Rosenbloom, J.I.; Gutman-Ido, E.; Lessans, N.; Cahen-Peretz, A.; Chill, H.H. Safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during pregnancy- obstetric outcomes from a large cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, Q.; Du, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women in real-world studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.iss. 2022.

- Huddleston, H.G.; Jaswa, E.G.; Lindquist, K.J. COVID-19 vaccination patterns and attitudes among American pregnant individuals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022, 4, 100507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuckelberger, S.; Favre, G.; Ceulemans, M. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine willingness among pregnant and breastfeeding women during the first pandemic wave: a crosssectional study in Switzerland. Viruses 2021, 13, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Wang, R.; Han, N. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum Vacc Immunother 2021, 17, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triunfo, S.; Marconi, A.M. Promoting the Use of Modern Communication Tools to Increase Vaccine Uptake in Pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triunfo, S.; Iannuzzi, V.; Podda, M. Reducing vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy by the health literacy model inclusive of modern communication tools. Arch Obstet Gynecol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Sanità. Progetto Obiettivo Materno Infantile D.M. 24 aprile 2000 pag.

- Grandolfo, M.E.; Donati, S.; Giusti, A. Indagine conoscitiva sul percorso nascita. Aspetti metodologici e risultati nazionali. I: Roma, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT Gravidanza, parto, allattamento al seno 2004-2005. Roma: Istat, 2006.

- https://www.sigo.it/wpontent/uploads/2021/05/PositionPaper_Gravidanza_Vaccinazione_anti_COVID_05.05.2021.

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983.

- WHO Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/The Depcare Project. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen. 1998.

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1983, 24, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novillo, B.; Martínez-Varea, A. COVID-19 Vaccines during Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2022, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Nayak, A.; Tiwari, D.; Pillai, P.K.; Pandita, A.; Sakharkar, S.; Balasubramanian, H.; Kabra, N. COVID-19 Disease in Under-5 Children: Current Status and Strategies for Prevention including Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Demir, R.; Kaya Odabaş, R. A systematic review to determine the anti-vaccination thoughts of pregnant women and the reasons for not getting vaccinated. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 2603–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisset, K.A.; Paterson, P. Strategies for increasing uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income countries: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2018, 36, 2751–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent Formby, Immunologic Response in Pregnancy: Its Role in Endocrine Disorders of Pregnancy and Influence on the Course of Maternal Autoimmune Diseases. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America 1995, 24, 87–205.

- Tan, E.K.; Tan, E.L. Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013, 27, 791e802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackin, D.W.; Walker, S.P. The historical aspects of vaccination in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021, 76, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, A.D.; Roguski, K.M.; Chang, H.H.; Muscatello, D.J.; Palekar, R.; Tempia, S.; Cohen, C.; Gran, J.M.; Schanzer, D.; Cowling, B.J. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018, 391, 1285–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafond, K.E.; Porter, R.M.; Whaley, M.J.; Suizan, Z.; Ran, Z.; Aleem, M.A.; Thapa, B.; Sar, B.; Proschle, V.S.; Peng, Z. Global burden of influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections and hospitalizations among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021, 18, e1003550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, A.K.; Fiddian-Green, A. Protecting pregnant people & infants against influenza: A landscape review of influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy and strategies for vaccine promotion. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2156229. [Google Scholar]

- Brosio, F.; Kuhdari, P.; Cocchio, S.; Stefanati, A.; Baldo, V.; Gabutti, G. Impact of pertussis on the Italian population: Analysis of hospital discharge records in the period 2001–2004. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabutti, G.; Cetin, I.; Conversano, M.; Costantino, C.; Durando, P.; Giuffrida, S. Experts’ Opinion for Improving Pertussis Vaccination Rates in Adolescents and Adults: A Call to Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjefte, M.; Ngirbabul, M.; Akeju, O. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mappa, I.; Luviso, M.; Distefano, F.A.; Carbone, L.; Maruotti, G.M.; Rizzo, G. Women perception of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during pregnancy and subsequent maternal anxiety: a prospective observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 6302–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engjom, H.; van den Akker, T.; Aabakke, A.; Ayras, O.; Bloemenkamp, K.; Donati, S.; Cereda, D.; Overtoom, E.; Knight, M. Severe COVID-19 in pregnancy is almost exclusively limited to unvaccinated women - time for policies to change. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022, 13, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escott, D.; Slade, P.; Spiby, H. Preparation for pain management during childbirth: the psychological aspects of coping strategy development in antenatal education. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009, 29, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, S. Literature Review of the Association Between Prenatal Education and Rates of Cesarean Birth Among Women at Low Risk. Nurs Womens Health. 2021, 25, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, R.; Hutchinson, A. A narrative review of parental education in preparing expectant and new fathers for early parental skills. Midwifery. 2020, 84, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kelly, S.M.; Moore, Z.E. Antenatal maternal education for improving postnatal perineal healing for women who have birthed in a hospital setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 12, CD012258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Sanità. Progetto Obiettivo Materno Infantile D.M. 24 aprile 2000 pag.8.

- Ricchi, A.; La Corte, S.; Molinazzi, M.T.; Messina, M.P.; Banchelli, F.; Neri, I. Study of childbirth education classes and evaluation of their effectiveness. Clin Ter. 2020, 170, e78–e86. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Absence of lesson | Presence of lesson | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| on vaccines | on vaccines | ||

| (n=33) | (n=112) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 33.9 (4) | 33.7 (5.1) | 0.207 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| - Caucasian | 32 (97) | 106 (93.8) | 0.007 |

| -Latino-American | 1 (3) | 3 (2.7) | 0.916 |

| -Asian | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.443 |

| -African | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.294 |

| Education Level | |||

| -Low | 3 (9.1) | 4 (3.6) | 0.221 |

| -Medium | 11 (33.3) | 44 (39.3) | 0.177 |

| -High | 19 (57.6) | 64 (57.1) | 0.095 |

| Working status | |||

| -Employed | 25 (75.8) | 99 (88.4) | 0.267 |

| -Unemployed | 8 (24.2) | 13 (11.6) | 0.64 |

| Smoking status | |||

| -None | 29 (87.9) | 97 (86.6) | 0.956 |

| -Smokers | 4 (12.1) | 15 (13.4) | 0.121 |

| Marital status | |||

| -Married o living with partner | 31 (93.9) | 110 (98.2) | 0.867 |

| -Unmarried | 2 (6.1) | 2 (1.8) | 0.503 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Substance abuse | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Variables | Absence of lesson | Presence of lesson | |

|---|---|---|---|

| on vaccines | on vaccines | p-value | |

| (n=33) | (n=112) | ||

| Medical condition | |||

| -Diabetes | 2 (6.1) | 5 (4.5) | 0.721 |

| - Hypertension | 1 (3) | 3 (2.7) | 0.916 |

| -Thyroid disease | 2 (6.1) | 15 (13.4) | 0.297 |

| -Neurological disease | 2 (6.1) | 4 (3.6) | 0.547 |

| - Autoimmune disease | 1 (3) | 4 (3.6) | 0.916 |

| Parity | |||

| -Primiparous | 22 (66.3) | 87 (77.7) | 0.622 |

| - Multiparous | 11 (33.3) | 25 (22.3) | 0.329 |

| Labor induction | 11 (33.3) | 46 (41.1) | 0.592 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| -Vaginal delivery | 22 (66.6) | 65 (58) | 0.661 |

| -Instrumental delivery | 2 (6.1) | 13 (11.6) | 0.400 |

| -Elective cesarean section | 2 (6.1) | 14 (12.5) | 0.345 |

| -Emergent cesarean section | 7 (21.2) | 20 (17.9) | 0.721 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).