1. Introduction

Among the many industries impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the food and beverage (F&B) industry is one of the fast-growing industries in the world because of its unique for fulfilling some of the most basic needs of humankind [

1]. As a major user of single-use packaging, the F&B sector plays an important role in addressing plastic pollution. Plastic pollution is an escalating environmental problem affecting nearly every ecosystem globally [

2]. A large percentage of global plastic waste leakage is estimated to come from Asia, and most of this is from food and drink packaging [

3].

Differences are indicated between individuals from developed and emerging countries which suggest that external factors (culture, environmental structures,

and services in each country) may play a relevant role in consumers’ behaviors towards the environment [

4]

. This study selects Taiwan and Indonesia as the case studies of developed and

emerging regions, respectively. In Indonesia, the

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the F&B industry grew positively by 3.49% in 2021 [

5], and meanwhile, the sales of the F&B industry also increased 43% in Taiwan [

6]. The growth of the F&B industry means that the amount of plastic usage subsequently increases.

Education produces strata in society which have their own distinct interests, values, and designs for living [

7]; in

short, education can foster perceived knowledge, and attitude intensity, and eventually influence intention and behavior. Consumers’ actions are commonly explained as being driven by attitudes based on the evaluation of expected costs and benefits. Environmental education is aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to help solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solution [

8]. The associations between general environmental attitude and pro-environmental behavior are heterogeneous and these associations depend on attitude intensity and the specific pro-environmental behavior [

9]. Besides, pro-environmental behavior is a complex concept that may be defined as any behavior that benefits the environment or, in the case of harming it, tries to do as little damage as possible to the environment [

10]. Unless consumers change their behaviors and show a respectful attitude toward the natural environment, we cannot expect the world’s economic prospects and society's welfare to be improved. To resolve the environmental problems, it is necessary to trigger consumers’ environmental awareness and therefore this highlights the importance of education on environmental knowledge.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Education and Environmental Knowledge

The concept of environmental education is now widespread in national educational policies, curriculum documents, curriculum development initiatives, and conservation strategies. The education base provides more information about consumers’ environmental knowledge and attitudes than about their educational experiences and preferences, and more about learning outcomes than about learning processes [

11]. Environmental education is considered to rethinking the relationship between humankind and the biosphere, as a tool for pushing social change toward a sustainable future, raising awareness and interest in environmental issues, and providing the skills to solve them [

12]. The individuals and groups who participate in environmental education programs have a better understanding of the causes and consequences of environmental issues, as well as a greater appreciation for the value of natural resources [

13]

Zsóka et al. reveal that a significant relationship exists between environmental education and environmental knowledge and find a strong correlation between the intensity of environmental education and environmental knowledge [

14]. In conclusion, environmental education is the fundamental part, allowing consumers to know and understand objective and tangible environmental facts and phenomena, and realize how to deal with, solve, or prevent environmental damage or worsening. Meanwhile, environmental education also enhances the understanding of the essence of the tangible natural environment, the unchanged abstract rules behind the natural environment, and the status and role of the natural environment [

15]. The important thing is that environmental education cultivates consumers’ environmental knowledge and environmental value to seek for getting along with the natural environment permanently. Herewith, we propose the following Hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Environmental education positively and significantly influences the consumer’s environmental knowledge perceived.

2.2. Environmental Education and Environmental Attitude

Environmental attitude refers to an individual's feelings, beliefs, and values about the natural environment and their role in protecting it [

16]. Environmental attitude regards the extent and nature of their environmental concern and/or indifference. Consumer’s attitude toward the environment is important because it can promote positive development and empower other people to actively contribute to the environment [

17]. Consumers’ environmental attitudes and knowledge need to be understood in order that they can be more effectively changed through educational interventions [

11]. The history of environmental education reveals a close connection between changing concerns about the environment and its associated problems and the way in which environmental education is defined and promoted [

18]. In short, consumers hold environmental attitudes to be achieved owing to the success of environmental education. An understanding of environmental attitudes is crucial because they are a precursor to pro-environmental behavior, which is the ultimate goal of environmental education [

19].

However, some literature indicates that environmental education may not be sufficient to significantly change consumers’ attitudes toward the environment. For example, Erhabor and Don find that environmental education programs improve environmental knowledge, but do not result in significant changes in environmental attitudes [

20]. One possible explanation for this disparity is that environmental attitudes are influenced by a complex set of factors. While environmental education can help raise environmental awareness and knowledge, it may not be enough to change deeply entrenched attitudes and values on its own. Even though the impact of environmental education on environmental attitudes is debatable, it is clear that education is a valuable tool for encouraging greater engagement and action on environmental issues. Environmental education teaches consumers how to weigh several sides of an issue through critical thinking, and it improves their problem-solving and decision-making in the purchase process [

21]. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: Environmental education positively and significantly influences the consumer’s environmental attitude.

2.3. Environmental Education and Environmental Behavioral Intention

Many studies pose a link between environmental education and pro-environmental intention regarding purchasing green products among college students in the United States, Spain, Mexico, and Brazil [

4]. If a person has received environmental education, they are more likely to act pro-environmentally intentions than if they did not [

22]. Examples of situations where direct measures are adaptable include an assessment of students’ learning after a stream ecology activity through a performance assessment, observations of students’ behaviors related to litter reduction and water pollution, and observations of students’ disposal of liquids into storm drains [

22]. These measures seek to attain their goals by increasing individuals’ pro-environmental behavioral attention as a consequence of increasing their knowledge and awareness about environmental issues. Consequentially, environmental education can enhance the intention of observing, examining, and assessing actual environmental behaviors, by being incorporated into educational measures in different ways. Thus, we posit that,

Hypothesis 3: Environmental education positively and significantly influences the consumer’s environmental behavioral intention.

2.4. Environmental Education and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Considering why a change of behavior needs to be made and how to make that change, the most critical and powerful influence comes from education.

Education is a broad term that encompasses the process of obtaining general knowledge, personal awareness, and skills training [

23].

Effective environmental education represents more than a unidirectional transfer of information; it develops the suite of tools enhancing environmental attitudes, values, and knowledge, as well as builds skills that make

individuals and communities collaboratively undertake well-informed environmental action [

24]

. To turn out the role of environmental education in developing, supporting, and sustaining the environmental actions of individuals and communities,

environmental education's contributions directly and positively relate

to conservation and environmental quality outcomes [

24]. Even though one argument from Boyes and Stanisstreet indicates that environmental education programs may not be designed in a way that encourages behavioral change, rather these programs primarily focus on increasing knowledge and awareness without critical thinking and action learning required [

25]. However, undeniably the researchers consider that education and awareness of environmental protection are important instruments for strengthening engagement and pro-action on environmental issues. Thus, we present Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 4: Environmental education positively and significantly influences the consumer’s pro-environmental behavior.

2.5. Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Behavioral Intention

Knowledge has been shown to be one of the key predictors in several theoretical models of the link between behaviors and attitudes. The consumers’ knowledge of environmental concerns and solutions may determine their selection of green product purchases [

26]. If consumers are fairly aware of general environmental issues, they are more likely to purchase green items. That is, when consumers’ environmental knowledge is higher, their purchase intention is expectedly higher. Most studies mention that increased environmental knowledge can lead to a greater sense of personal responsibility for environmental protection, whether through intention or behavior. For example, some studies verify a directly positive relationship between environmental knowledge and green purchase intention [

27,

28]. Environmental knowledge has an appreciable effect in explaining purchase intention [

29].

In contrast to other empirical scientists, some researchers state that environmental knowledge is a predictor with the lowest value of its influence on green purchase intention [

30]. The existence of gaps in the studies mentioned above encourages this article to conduct similar research elsewhere, for which the hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 5: A consumer’s environmental knowledge is perceived positively and significantly influences the consumer’s environmental behavioral intention.

2.6. Environmental Attitude and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Attitude is a psychological factor that is considered an important variable in predicting action [

31]. Likewise, one of the factors that demonstrate consumers' environmental responsibility for their behaviors is their environmental attitude. Customers with good attitudes toward environmental sustainability are more likely than those with negative attitudes to engage in environmentally friendly practices [

32]. Environmental attitude is crucial in transforming environmental knowledge into behaviors [

30]. As attitude accounts for the highest weight of variance in purchase intention, attitude can be considered a strong predictor of behavior [

29]. Since the environmental movement of the 1960s, green consumption has been identified as a pro-environmental behavior [

33]. Only consumers who are ‘‘true believers’’ in environmental protection can engage in pro-environmental behaviors. A green consumer actually takes physical environmental issues (e.g., environmental preservation, reducing pollution, responsible use of non-renewable resources) into account while making consumption decisions [

34].

In other words, an environmentalist (i.e., a person who aspires to protect the environment and who, one might assume, holds a pronounced pro-environmental attitude) is typically expected to engage in a set of activities that reflect his or her attitude [

35]

. Herewith, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6: The consumer’s environmental attitude positively and significantly influences the consumer’s pro-environmental behavior.

2.7. Environmental Behavioral Intention and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Intention usually can carry out a specific behavior and is also a crucial component of the driving force in the decision-making process [

36]. An individual who has an extremely clear intention of when, where, and how, he/she will strive to carry out the action [

37]. A study primarily focusing on the difference between ethical purchase intention and actual purchasing

behavior, finds that the implementation intention leads to behavior [

38]. On the contrary, some studies argue individuals may face external barriers that prevent them from engaging in pro-environmental behavior, even if they have a strong intention to do so [

39]. For example, if there are no alternative products available or if they live in an area without access to recycling facilities, an individual may find difficulty in reducing the usage of single-use plastics. Besides, personality, values, and beliefs may also play different roles in the relationship between environmental intention and behavior [

40]. Individuals may be more likely to see pro-environmental actions as socially desirable and normative when they understand the environmental consequences due to their behaviors. Thus, we present the Hypothesis

Hypothesis 7: The consumer’s environmental behavioral intention positively and significantly influences the consumer’s pro-environmental behavior.

2.8. Environmental Motivation as a Moderating Variable

A moderator variable is a qualitative

(e.g., gender, SES) or quantitative (e.g., amount of social support) variable that affects the direction and/or strength of the relationship between

an independent or predictor variable and a dependent or criterion variable [

41]

. This exploratory investigation is undertaken to determine if environmental education is a more meaningful predictor of certain aspects of consumers’ pro-environmental behavior when environmental motivation is included as a moderating variable. Moderating and mediating variables, or simply moderators and mediators, are related but distinct concepts in both general statistics and their application in psychology. A moderating variable is a variable that affects the relationship between two other variables [

42]. Since more knowledgeable consumers are more likely to perceive fewer barriers to environmental behavior or intention and then become highly motivated to act in an eco-friendly manner [

43]. Motivation as an important educational component has been recently acknowledged in several educational-related fields. Consumers are aware that doing the right thing sends a positive self-signal; the act of helping actually makes consumers feel good, both physically as well as psychologically [

44]. Individuals who engage in environmental behavior primarily for external rewards or recognition, and may be less likely to internalize pro-environmental values and attitudes. As a result, while designing and implementing environmental education programs, it is critical to consider the role of environmental motivation [

45]. This article stresses the importance of understanding the intrinsic motivational basis between environmental education and pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, the following hypothesis is posited.

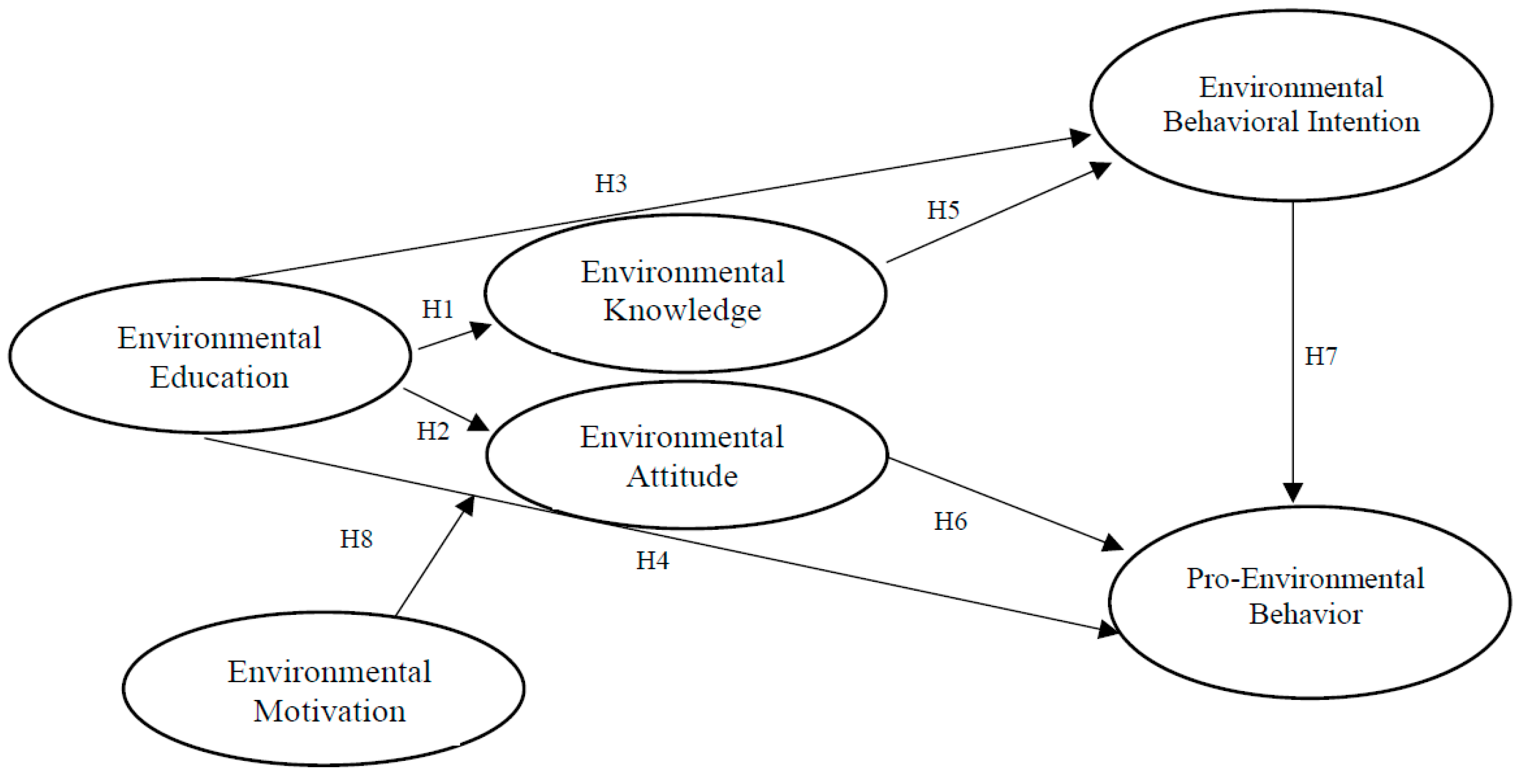

Hypothesis 8: Environmental education positively and significantly affects the consumer's pro-environmental behavior via environmental motivation as a moderating variable. We summarize eight Hypotheses proposed in this article as shown in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Paradigm Design and Collecting Data

Based on the above-mentioned literature review and nine hypotheses proposed, we adopt the post-positivism paradigm which is a philosophical belief that develops and supports objective, patterned, and knowable reality and which makes and testifies claims of this study [

46]. This study uses quantitative research comprising measure variables to testify the relationships between variables. Data generated by quantitative research methods are typically collected through structured questions [

47]. Thus, we do a survey method in the form of an electronic questionnaire for gathering a large number of responses and easily access the valid samples. In conducting the survey, we distribute a total of 350 questionnaires using Google Form links sent to friends, family members, and chatting groups through LINE and WhatsApp from March 11 to April 30 in 2023 and then get the valid 235 samples including 110 Indonesian respondents and 125 Taiwanese respondents.

Basically, data can be divided into numerical and categorical data. Numerical data contains numbers that we can manipulate using ordinary arithmetic operations, in a while, categorical data can be sorted into categories classified as nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio. Under this research conceptual framework and operational definitions, we use an interval scale which means that respondents can store their answers in the form of an agreement level [

46]. The technique of the interval scale used is the Likert scale. A Likert scale is a psychometric scale that has multiple categories from which respondents choose to indicate their opinions, attitudes, or feelings about a particular issue [

48]. Therefore, we employ a five-point Likert scale for measuring personal behavior through questionnaires. Typically, there are five categories of response, from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree.

3.2. Validity and Reliability Test

The confirmatory analysis consists of validity and reliability tests to test the concepts built using several measurable indicators. A validity test is conducted to ensure the accuracy of variable measurement indicators and is classified into two types: convergent validity test and discriminant validity test. This study employs Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) as the tools for testing the validity. Convergent validity refers

to how closely a test is related to other tests that measure the same (or similar) constructs. Meanwhile, discriminant validity shows how unique or different a measure is [

49]; that is, among those constructs, each should have no relationship with others.

The most commonly used internal consistency measure is the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. It is viewed as the most appropriate measure of reliability when making use of the Likert scale [

50]. However, Cronbach's Alpha provides an estimate of the internal consistency of the test, but alpha does not indicate the stability or consistency of the test over time. Besides, construct reliability (CR) provides a higher reliability value than Cronbach's Alpha [

51]. Therefore, this study adopts CR as the instrument for measuring reliability. A confirmatory analysis is good if the CR value is > 0.7 and the variance extracted value is > 0.5.

3.3. Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling

A bunch of literature has considered structural equation modeling (SEM) a mathematical tool for drawing causal conclusions from a combination of observational data and theoretical assumptions Duncan e.g., [

52,

53]. However, the role of causality in SEM research is widely perceived to be, on one hand, of pivotal methodological importance and, on the other hand, confusing, enigmatic, and controversial [

54]. SEM is dominantly practiced in management research that generates theoretical tests rather than developed theory, particularly in covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM). Nevertheless, CB-SEM is measured to illustrate its use in exploring the association between consumer attitude and consumer purchasing behavior. Accordingly, this study employs CB-SEM, which conducts the relationship among latent constructs and how well they fit through measured variables to perform the indicators of constructs using AMOS software.

In working on SEM, there are four assumption tests – large sample size, data normality test, measurement model test, and validity test that must be fulfilled [

51]. The sample size requirement in CB-SEM should not be a problem as long as the sample size used is at least one hundred data [

55]. If the data is not normally distributed, the bootstrapping method can be implemented for testing hypotheses in AMOS software. The valid measurement model can be observed through a validity test. Finally, the measurement scale used in the study must be an interval scale [

51].

3.3.1. Measurement model test

In order to specify the measurement model, we make the transition from factor analysis, in which the researcher has no control over which variables describe each factor, to a confirmatory mode, in which the researcher specifies which variables define each construct (factor). The manifest variables we collected from the respondents are ‘indicators’ for the measurement model because we use them to measure or indicate the latent constructs (factors). The most obvious difference between the measurement model and factor analysis is that the former has a much smaller number of loadings and resembles the exploratory mode of factor analysis. Researchers can specify a measurement model for both exogenous constructs and endogenous constructs [

57].

3.3.2. Structural model test

The structural model test represents the theory that determines how constructs are related to each other which determines whether or not a hypothesis exists. Before testing the hypothesis, we need to check the R-Square. R-Square shows how much percentage of variation in the dependent variable can be explained in the independent variable [

56]. While conducting structural testing, this study uses several measurement standards, CR, and p-value with a minimum of more than 1.65 and > 0.05 [

58].

3.4. Moderation Analysis

The main objective of moderation analysis is to measure and test the differential effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable as a function of the moderator. Special attention is required in moderation analysis since it can be influenced by multi-collinearity, which makes estimates of regression coefficients unstable. In an analysis with a moderating term – i.e., an interaction effect, the product of the variables can be strongly related to either the independent or the moderating variable, or both of them. If two variables are collinear, one of them can be centered on its mean. In this way, half of its value becomes negative, and consequently, collinearity decreases [

42]. Additionally, whichever statistical package is used, researchers must take care of the following three key points while performing a moderation analysis [

59]. First, the research should focus on the significance of the moderating effect (Z). Second, researchers must calculate and report the effect size (

f2), and how much it contributes to

R2 as a function of the moderator. Lastly, researchers must execute and report a simple slope plot for the visual inspection of the direction and strength of the moderating effect.

3.5. Model Fit Test

Various measures evaluate the fit of the model. The use of the chi-square test is reasonable when the study involves a large sample [

60]. The first measure is the likelihood ratio chi-square statistic. While the value has a statistical significance level above the minimum level of 0.05, the statistics support the argument that the differences between the predicted and actual matrices are insignificant, indicative of an acceptable fit. However, as the chi-square was very sensitive to sample size, the degree of freedom could be used as an adjusting standard to judge whether the chi-square is large or small [

61]. The model fit assessment approach is involved, using several diagnostics to judge the simultaneous fit of the measurement and structural models to data collected for this study. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) is another measure. The adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) is an extension of the GFI, adjusted by the ratio of degrees of freedom for the proposed model to the degrees of freedom for the null model. Other types of fit measures include the Comparative-Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). This study uses CFI to explain the difference between the model and the independent model without co-variables. The closer the value is to 1, the better the model fit. The RMR is the square root of the mean of the squared residuals — an average of the residuals between observed and estimated input matrices [

61].

4. Research Result

4.1. Validity and Reliability Testing Result

The first test is to determine the validity of the construct. Furthermore, the value of each indicator is used to determine convergent validity. The concept validity test is classified into two types: convergent validity test and discriminant convergent validity test. In this work, the validity test employs Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

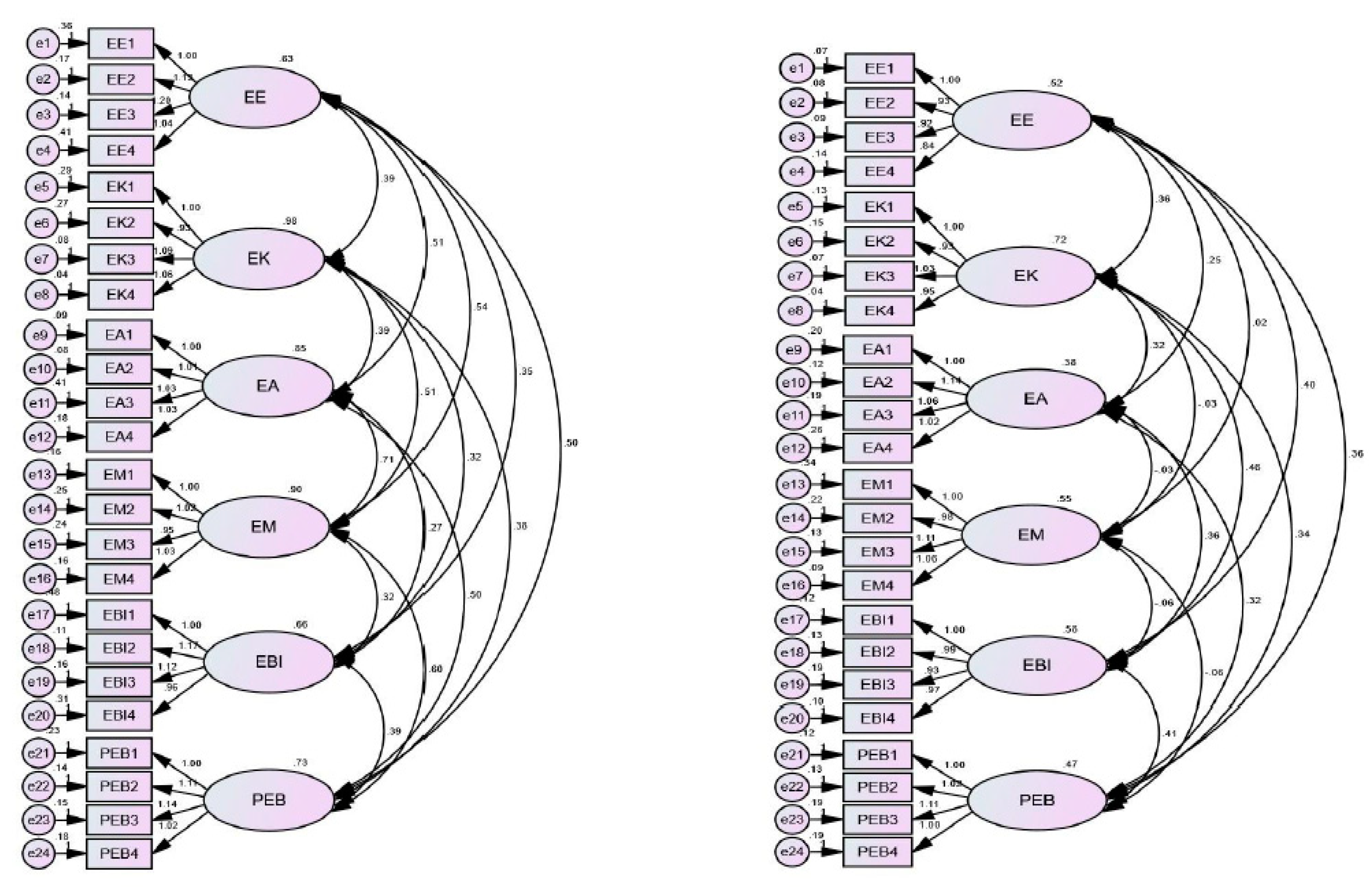

Figure 2A,B illustrate the CFA results for Indonesia and Taiwan. The variables include environmental education (EE), environmental knowledge (EK), environmental attitude (EA), environmental motivation (EM), environmental behavioral intention (EBI), and pro-environmental behavior (PEB). Validity testing can be seen through Average Variance Extracted (AVE) in addition to using the standardized loading estimate.

Table 1 and

Table 2 show that the AVE value of all variables is regarded to be valid because it is more than 0.5. The discriminant validity test comes after the convergent validity test. If the value of the root AVE is greater than the value of the correlation coefficient, the discriminant validity test is valid. Regarding the definitions of EE1, EE2, EE3, EE4, EK1, EK2, EK3, EK4, EA1, EA2, EA3, EA4, EM1, EM2, EM3, EM4, EBI1, EBI2, EBI3, EBI4, PEB1, PEB2, PEB3, and PEB4, please refer the

Appendix A.

Figure 2.

(A,B) The CFA result for Indonesia.

Figure 2.

(A,B) The CFA result for Indonesia.

As for reliability testing results, the CR values for variables of environmental education, environmental knowledge, environmental attitude, environmental motivation, environmental behavioral intention, and pro-environmental behavior are shown in

Table 1 (Indonesia), and

Table 2 (Taiwan), respectively, which are greater than 0.7. That means all variables in this preliminary research study can be declared reliable.

4.2. Normality Testing Result

In testing the measurement model, we need to conduct a normality test. This result can be observed from the CR value of skewness ± 2.58 which indicates the data being normally distributed. Based on

Table 3, all indicators are normally distributed because they have CR values of skewness ± 2.58.

4.2. Structural Model Testing Result

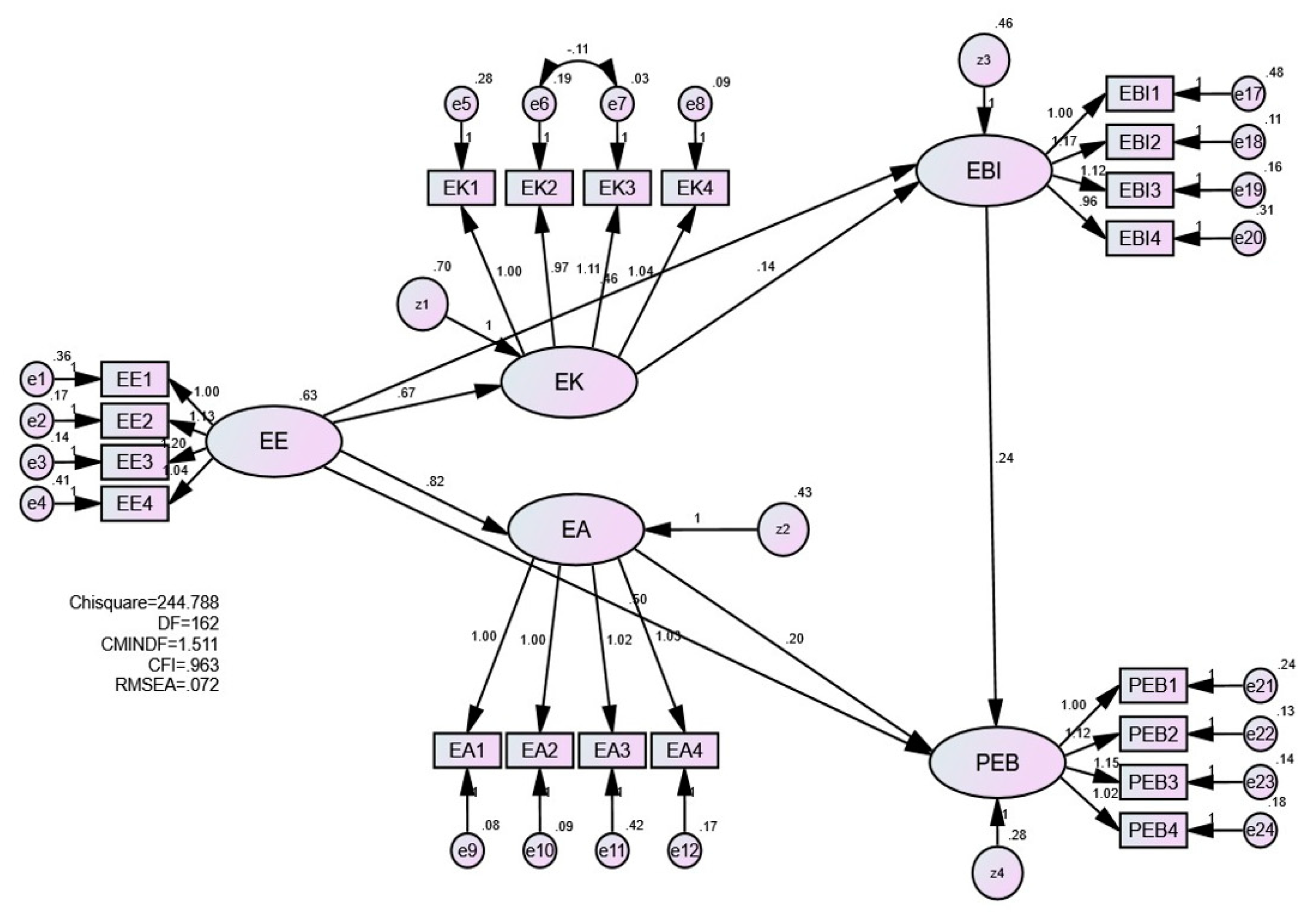

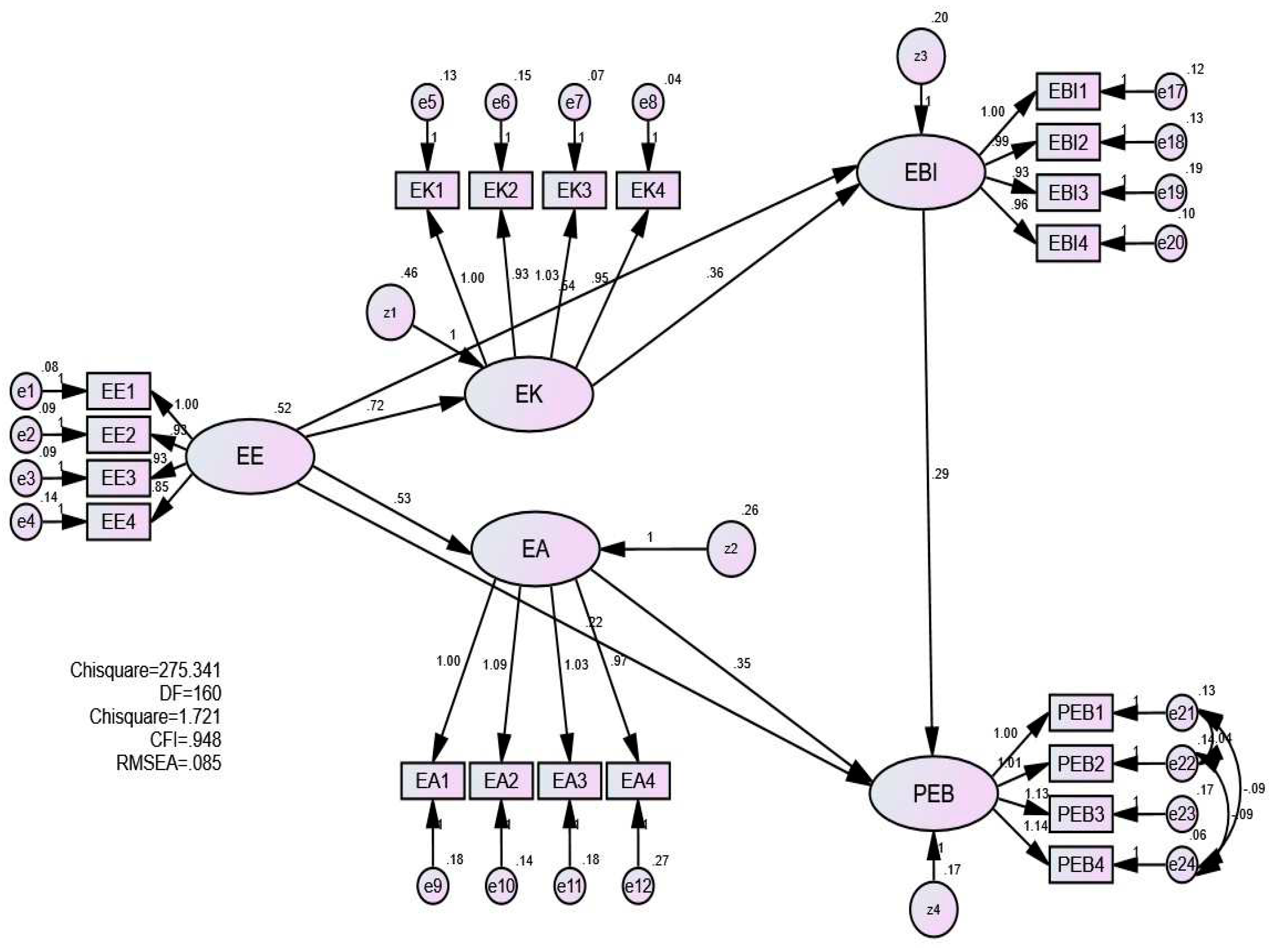

A hypothesis is supported if there is a significant relationship that has a value of ± 1.65. In conducting a structural model, it is also necessary to see the criteria for the model fit.

Figure 3 (Indonesia) and

Figure 4 (Taiwan) illustrate the results of testing the structural model, which describes the endogenous latent variables in this study along with the R-Square value of each endogenous observed from the Squared Multiple Correlations. As the R-Square value of the EK variable, 0.287 for Indonesia, which means that 28.7% of the existing variations can be explained by the EE variable falls into the weak category and 0.367 for Taiwan, which means that 36.7% of the existing variations can be explained by the EE variable is included in the moderate/medium category. Regarding the R-Square value of the EA variable, 0.494 of Indonesia and 36.0% of Taiwan mean that both have a moderate/medium explanation rate. As to the R-Square value of the EBI variable, 0.308 in Indonesia and 0.661 in Taiwan show a moderate/medium or higher explanation rate. With regard to the R-Square value of the PEB variable, 0.621 of Indonesia and 610% of Taiwan mean that both have higher explanation rates. In the final, the result of the hypotheses testified by this study is summarized in

Table 4.

Most of all hypotheses except H5 are supported for the Indonesian survey; on the other hand, in Taiwan’s survey, H7 is rejected, and the rest of the hypotheses are supported. Regarding H1, the findings and results from Indonesian and Taiwanese investigations show that one of the main environmental education’s objectives is to increase individuals’ knowledge and awareness about environmental issues. Some other empirical studies’ evaluations have also found significant changes in environmental knowledge influenced by environmental education [

62]. Consequently, performance assessments in science education test the ability of consumers to use their knowledge for carrying out their activities or behaviors.

Even though some studies show that there is no significant change in children’s attitudes after an outdoor environmental education program [

63]. However, in our study, the empirical test evidence indicates there is a positive and significant relationship between environmental education and environmental attitude. That is, H2 is supported both in Indonesia and Taiwan. As well known, several environmental education programs developed by whatever school or government aim to change attitudes and behaviors, and promote students’ and citizens’ environmental literacy and environmentally sustainable actions [

22].

From the result of H3, the findings state that there is a positive and significant relationship between environmental education and environmental behavioral intention. Environmental education drives consumers to engage in pro-environmental activities and has a positive impact on environmental behavioral intention through improving knowledge and awareness, modifying attitudes, and influencing social norms. Moreover, social norms, which are generated within individuals through informal education and the media, seem to influence pro-environmental behavior through attitudes and behavioral intentions [

64], so informal environmental education seems to be also essential for individuals to acquire environmentally favorable attitudes. Environmental education plays an important role in altering individuals’ willingness to engage in a specific environmental issue [

4].

The result of H4 examined, the findings to prove that there is a positive and significant relationship between environmental education and pro-environmental behavior. The role of environmental education in developing, supporting, and sustaining the environmental actions of an individual and the community directly and positively affects environmental quality and conservation outcomes [

24]. Environmental education encompasses approaches, tools, and programs that foster and support environmentally related attitudes, values, awareness, knowledge, and skills, and further disciplines consumers to prepare and actually take informed environmental action.

Our results are, in general, consistent with previous research that highlights the significance of knowledge and formal education in pro-environmental attitude and behavior. However, while we examine the relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental behavioral intention (H5), the surveys of Indonesia and Taiwan show different results. A positive and significant relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental behavioral intention exists in Taiwanese consumer purchasing, but the phenomenon does not appear in Indonesian consumer purchasing. The main conclusion in regard to differences between emerging and developed regions is that this economic-development-related classification cannot be applied simplistically to environmental performance. Moreover, pro-environmental behavior intention is analyzed as the sum of all components and the results reveal that different patterns occur in each context. These patterns are probably due to the different cultural habits and structures that exist in each region [

24].

Attitude is a significant variable in explaining pro-environmental behavior. Not surprisingly, H6 is supported in both Indonesia and Taiwan contexts. There is a positive and significant relationship between environmental attitude and pro-environmental behavior. In this sense, Indonesian and Taiwanese consumers have the most favorable attitudes towards the environment and consumers from these two regions have the highest levels of pro-environmental behavior. Finally, environmental attitude allocates the most importance to price in consumer activities. Vicente-Molina et al. mentions that the level of environmental knowledge and the role of environmental education in changing and addressing lifestyles and attitudes could be crucial in altering individuals’ behavior and in turning society towards sustainability [

24].

H7 refers to a positive and significant relationship between environmental behavioral intention and pro-environmental behavior. Unexpectedly, this hypothesis is supported in the Indonesian context, but not supported in the Taiwan context. Some studies use the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as a framework for predicting behavioral intention relative to green product (i.e., eco-friendly or pro-environmental) purchases [

65]. In a previous study, Wu and Chen propose that 80% of the variance in actual purchasing behavior (measured by a preference for purchasing green options) is explained by purchase intention with a sample of Taiwanese consumers [

66]. Thus, due to this documented explanatory power of purchase intention in the context of green purchase behaviors, intention alone is selected as the dependent variable. However, Choi and Johnson’s survey of Taiwanese consumer behavior indicates when the three constructs (subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and attitude toward purchasing green products) of the TPB are controlled along with demographic variables, the significance of the variance of perceived environmental effectiveness (PEE) accounted for disappeared [

29]; that means “not supported.’’ PEE is an issue-specific motivation for consumption, an estimate of the degree to which one’s own consumption decision (i.e., purchasing green products) provides an answer to specific environmental issues. Their Findings support the claim that it is situation and issue-specific motivations that are direct constructs of a specific behavior rather than general motivations. Based on the arguments above, we propose “environmental motivation” as a moderating variable for examining the relationship between environmental education and pro-environmental behavior. We present the result of the empirical test in the next section.

4.3. Moderation Testing Result

In this study, a moderation test is conducted by Moderated Regression Analysis (MRA) to examine the effect of specific interactions by entering a third variable (environmental motivation) in the form of the product of two independent variables to serve as a moderating variable.

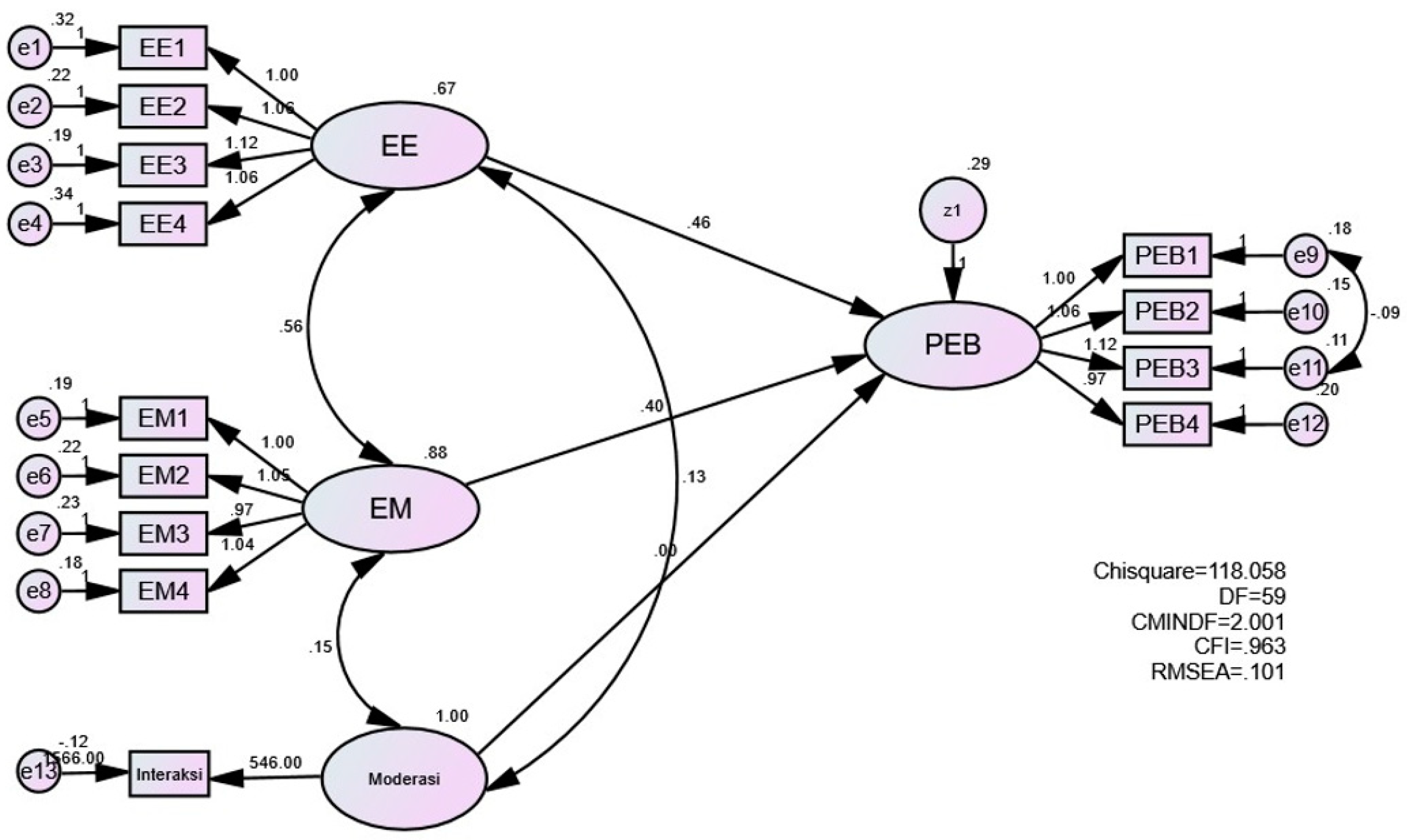

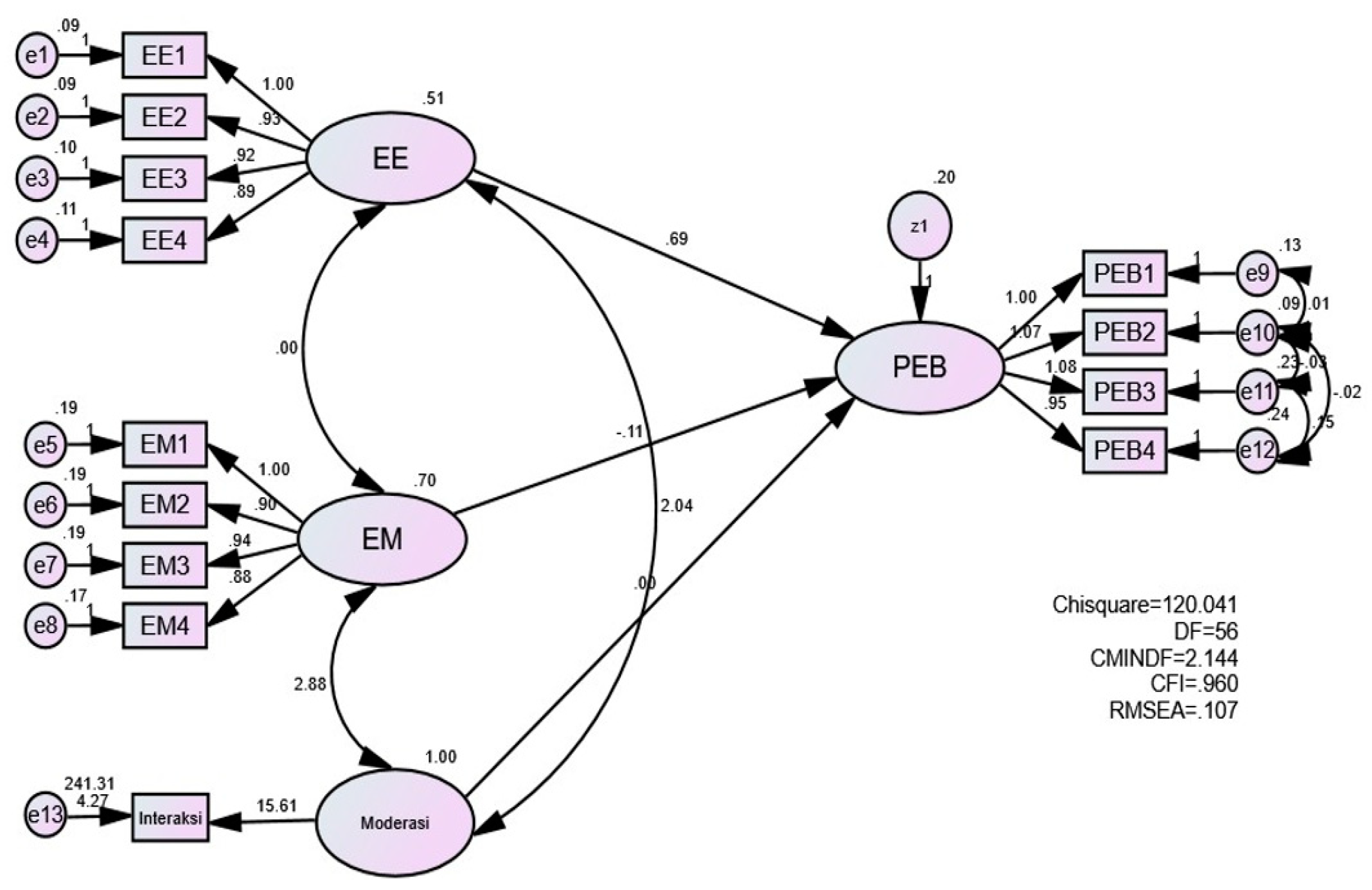

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 below are the pictures after entering the multiplication variable into moderation for Indonesia and Taiwan, respectively.

After completing the MRA test, on the one hand of Indonesia,

Table 4 shows the overall analyses for Indonesia and Taiwan. On one hand, in the Indonesian context, environmental education has a direct effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of 0.460 and significance. Environmental motivation also has a direct effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of 0.405 and significant. The interaction variable between environmental education and environmental motivation indicated no significant effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of -0.010. On the other hand in Taiwan, environmental education has a direct effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of 0.695 and significant. However, environmental motivation has no direct effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of -0.111. Going to the further step, we also find that the interaction variable between environmental education and environmental motivation has no significant effect on pro-environmental behavior with a value of 0.001.

Table 6 shows the model fit index for Indonesian and Taiwanese studies. Consequently, H8 is not supported in the Indonesian context, and also in the Taiwanese context. In the classic assumption test, we get the model fit index using AMOS. This step is indispensable because it can determine whether items are suitable for the specified model through the observed or sample data.

Table 5.

MRA Analyses for Indonesia and Taiwan.

Table 5.

MRA Analyses for Indonesia and Taiwan.

| |

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P-Value |

| Indonesia |

EE→PEB |

0.460 |

0.121 |

3.810 |

0.000 |

| Taiwan |

|

0.695 |

0.086 |

8.057 |

0.000 |

| Indonesia |

EM→PEB |

0.405 |

0.103 |

3.940 |

0.000 |

| Taiwan |

|

-0.111 |

0.060 |

-1.833 |

0.670 |

| Indonesia |

EE→EM→ PEB |

-0.010 |

0.002 |

-0.550 |

0.583 |

| Taiwan |

|

0.001 |

0.002 |

0.413 |

0.680 |

5. Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

The eight Hypotheses have been examined based on the acquired data. This study explores the relationships among environmental education (EE), environmental knowledge (EK), environmental attitude (EA), environmental motivation (EM), environmental behavioral intention (EBI), and pro-environmental behavior (PEB) in two distinct regions, and compares the difference of Indonesia context and Taiwan context. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) has been employed to evaluate the interplay between these variables. The primary motivation behind this research is to provide a comparative analysis and offer recommendations for improvement for both areas. Furthermore, it sheds light on the current state of consumer pro-environmental behavior and provides valuable insights. The findings may contribute to offering suggestions and solutions to enhance consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors in doing purchase process.

This study reveals that both areas exhibit similarities in pro-environmental behavior, but notable differences still emerge. Surprisingly, some of the findings contradict the hypotheses initially proposed. In the Indonesian study, two hypotheses are not supported: H5 and H8. In the Taiwan study, two hypotheses are not supported: H7 and H8. Although the study indicates similar pro-environmental behavior among consumers, this may not totally reflect the reality of everyday life. The similarity occurs because, under moral considerations, individuals possess a general understanding of what actions are beneficial for the environment and thus tend to choose “agree” or “very agree” with most of the indicators.

The finding is similar to recent research revealing that environmental knowledge does not always lead to pro-environmental behavior [

67]. One possible explanation is that consumers know what is wrong or harmful to the environment, but consumers usually choose opportunistic alternatives. Overall, we consider that it is very important to educate consumers aware of local and global environmental issues, knowledgeable about the impact of consumer behavior on the environment, and to foster eco-centrism, a point of view that recognizes the ecosphere, rather than the biosphere to the public.

Additionally, this study proves that motivation is not necessarily an influential factor in transforming tangible or intangible education into realistic behavior. However, this does not imply that environmental motivation is not crucial. Undeniably, motivation evokes the individual’s sustaining effort and drives committed initiative and enthusiasm. Previous researchers state that motivation cannot build itself from everyone's heart (intrinsic motivation), and it still needs encouragement from outside (extrinsic motivation) such as government regulations, circle friends, public or influencer figures, etc. [

44] After the emotional system is activated, there is a higher likelihood for consumers to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. Therefore, numerous consumers hold the belief in doing the right thing and will be motivated to conduct more ecological behaviors.

5.2. Implication

After concluding this research, the subsequent steps involve drawing implications. Based on the findings of the conducted analysis, this study outlines the implications arising from the results. The implications are divided into two parts: one pertaining to Indonesia and the other referring to Taiwan. For Indonesia, three major implications are remarked. Firstly, Indonesia should prioritize and consider implementing environmental education programs. Educators need to be cognizant of these distinct traits and their impact on students, thereby harnessing their innate curiosity and driving them to learn new and more difficult tasks. Furthermore, education must be taken more seriously, as it can generate awareness among individuals, shape societal norms, and gradually transform people’s mindsets. With advancements in technology, people/consumers are no longer limited to learning solely within the confines of educational institutions. Secondly, the government must be assumed a prominent role in society, and launch new environmental-friendly policies or regulations in the communities. The government strongly asks for citizens’ commitment to the policies/regulations. Thirdly, business owners should take proactive measures to produce or provide environmental-friendly alternatives. These efforts aim to facilitate Indonesian progress in fostering consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors. For instance, in the food and beverage industry, businesses take the initiative to ban the use of single-use plastic cups and transit to exploit paper cups instead.

In comparison to Indonesia, Taiwan has made remarkable strides in promoting pro-environmental behavior. This achievement can be attributed to the presence of well-defined regulations and policies, for instance, the implementation of policies facilitating waste separation and limiting the use of single-use plastics in purchasing food and beverage. Nonetheless, three implications are argued for Taiwan to enhance its pro-environmental behavior. Firstly, the government should establish a robust monitoring and evaluation system to ensure the efficient implementation of existing policies by businesses and other sectors. Secondly, Taiwan can prioritize the enhancement of public awareness and engagement by actively promoting environmental education and encouraging increased public participation. This can be achieved through various means, such as organizing impactful awareness campaigns, establishing partnerships with educational institutions, and harnessing the power of social media platforms to reach a wider audience. Similarly to Indonesia, the government can collaborate with influencers or public figures to deliver educational campaigns on environmental topics, leveraging their influence to effectively reach and engage a broader audience. Thirdly, it is necessary to actively promote and encourage collaboration between various stakeholders to advance pro-environmental behavior. These achievements can be completed through the establishment of public-private partnerships. Businesses, government agencies, non-profit organizations, and community groups join forces together to implement sustainable initiatives. By leveraging the diverse expertise, resources, and knowledge of different stakeholders, Taiwan can foster a collective and synergistic effort towards building a more environmental-friendly society with consciousness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-W.L; Methodology, C.-W.L.; Software, Y.-J. L..; Formal analysis, Y.-J. L.; Investigation, S.-J. P.; Resources, S.-J. P.; Data Curation, S.-J. P.; Writing—original draft preparation, C.-W.L; Writing—review and editing, C.-W.L; Supervision, C.-W.L.; Project Administration, Y.-J. L.; Funding Acquisition, S.-J. P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Chung Yuan Christian University (No. 2023510102, 1 March 2023).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Dear, all,

The purpose of this questionnaire is to understand how much importance of environmental education for consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. Please fill in the answers carefully and truthfully based on your actual situation. All information obtained in this questionnaire is only used as a reference for academic research, thank you!

Sincerely yours,

Prof. Ph.D. Cheng-Wen Lee,

Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan

No. 200, Zhongbei Rd., Zhongli Dist., Taoyuan City 320314, Taiwan (R.O.C.)

E-mail: chengwen@edu.edu.tw |

1. Basic information:

Gender: □Male □Female;

Age: □ 17-27 years old □ 28-38 years old □ 39-49 years old □ 50-61 years old

□ 61 years old or over

Educational level: □ High school or community diploma □ Bachelor’s degree

□ Master’s degree □ Doctoral degree

2. Please select it if you feel it is appropriate. Number 5 means “Strongly Agree”,

4 is “Agree”, 3 is “Neutral”, 2 is “Disagree”, and 1 is “Strongly Disagree”.

| |

|

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

| EE1 |

I am knowledgeable about the causes and effects of climate change. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EE2 |

I am familiar with the environmental laws and regulations of my country |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EE3 |

I have received formal education or training related to environmental issues. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EE4 |

I have participated in environmental education programs and events. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EK1 |

I have a good understanding of the benefit of recycling and waste reduction. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EK2 |

I am knowledgeable about the impacts of pollution on human health and the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EK3 |

I am familiar with the principles of sustainable development. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EK4 |

Compared to the average person, I am more familiar with issues related to the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EA1 |

I believe that everyone has a responsibility to protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EA2 |

I am willing to make changes to my lifestyle to protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EA3 |

I believe that government should take more action to protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EA4 |

I think that environmental protection should be a top priority for business and non-business. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EM1 |

I am motivated to protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EM2 |

I believe that protecting the environment is important for future generations. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EM3 |

I feel a sense of responsibility to protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EM4 |

I am willing to volunteer my time to help protect the environment. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EBI1 |

In the near future, I intend to reduce my use of single-use plastic. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EBI2 |

In the near future, I intend to use reusable bags instead of plastic bags when shopping. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EBI3 |

In the near future, I plan to learn more about environmental issues and how to live a more suitable lifestyle. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| EBI4 |

In the next future, I plan to purchase more environmentally friendly products. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| PEB1 |

I recycle and separate waste regularly. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| PEB2 |

I bring my own shopping bag when I am shopping. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| PEB3 |

I bring my own bottle when buying beverages. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

| PEB4 |

I support environmentally responsible businesses and products. |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

References

- Chowdhury, M.T.; Sarkar, A.; Paul, S.K.; Moktadir, M.A. A case study on strategies to deal with the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in the food and beverage industry. Operations Management Research 2022, 15, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; McGivern, A.; Murphy, E; Jambeck, J; Leonard, G. H.; Rochman, C.M. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, A.; Meissner, K.; Humphrey, J.; Ross, H. Plastic pollution and packaging: Corporate commitments and actions from the food and beverage sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 331, 129827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolanda, F. Industri Makanan dan Minuman Tetap Tumbuh Positif Selama Pandemi. Available online: https://ekonomi.republika.co.id/berita/r43izl370/industri-makanan-dan-minuman-tetap-tumbuh-positif-selama-pandemi (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Shih, T.Y.; Wickramasekera, R.; Li, D. Export development of Taiwanese food and beverage processing SMEs: A test of a DOI model. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2022, 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.L.; Rodeghier, M.; Useem, B. Effects of education on attitude to protest. American Sociological Review 1986, 51, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, W.B.; Bennett, D.; Bryan, W.; Fulton, J.; MacGregor, J.; Nowak, P.; Havlick, S. The concept of environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education 1969, 1, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escarioosé, J.-J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2019, 149, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, B. C. (1978). Systems approach to the concept of environment.

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, L. Based on environmental education to study the correlation between environmental knowledge and environmental value. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 2018, 14, 3311–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoya, Y.; Khan, M.S.R. Financial literacy in Japan: New evidence using financial knowledge, behavior, and attitude. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhlerengen, M.; Wiium, N. Environmental attitudes, behaviors, and responsibility perceptions among Norwegian youth: Associations with positive youth development indicators. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 844324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilbury, D. Environmental education for sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environmental Education Research 1995, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, J.A.; o’Connor, M. Environmental education and attitudes: Emotions and beliefs are what is needed. Environment and Behavior 2000, 32, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhabor, N.I.; Don, J.U. Impact of environmental education on the knowledge and attitude of students towards the environment. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2016, 11, 5367–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela-Candamio, L.; Novo-Corti, I.; García-Álvarez, M.T. The importance of environmental education in the determinants of green behavior: A meta-analysis approach. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 170, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C.; Shavelson, R. Direct measures in environmental education evaluation: Behavioral intentions versus observable actions. Applied Environmental Education and Communication 2009, 8, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, K.R.; Johnston, C.A. Advocating for behavior change with education. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2018, 12, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological conservation 2000, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, E.; Stanisstreet, M. Environmental education for behaviour change: Which actions should be targeted? International Journal of Science Education 2012, 34, 1591–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriani, I.A.D.; Rahayu, M.; Hadiwidjojo, D. The influence of environmental knowledge on green purchase intention the role of attitude as mediating variable. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding 2019, 6, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Predictors of young consumer’s green purchase behaviour. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2016, 27, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A.H.L.; Harun, A.; Hussein, Z. The influence of environmental knowledge and concern on green purchase intention: The role of attitude as a mediating variable. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 2012, 7, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paco, A.F.; Raposo, M.L.; Filho, W.L. Identifying the green consumer: A segmentation study. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 2009, 17, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Science of the total environment 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Tamaki, T.; Managi, S. (2019). Effect of environmental awareness on purchase intention and satisfaction pertaining to electric vehicles in Japan. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2019, 67, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Antecedents of Egyptian consumers' green purchase intentions: A hierarchical multivariate regression model. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2006, 19, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; McCarty, J.A.; Lowrey, T.M. Buyer characteristics of the green consumer and their implications for advertising strategy. Journal of Advertising 1995, 24, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Merten, M.; Wetzel, E. How do we know we are measuring environmental attitude? Specific objectivity as the formal validation criterion for measures of latent attributes. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2018, 55, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Prybutok, V.; Blankson, C. An environmental awareness purchasing intention model. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2018, 119, 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Mangmeechai, A. Understanding the gap between environmental intention and pro-environmental behavior towards the waste sorting and management policy of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimehfar, F.; Halpenny, E.A. How do people negotiate through their constraints to engage in pro-environmental behavior? A study of front-country campers in Alberta, Canada. Tourism Management 2016, 57, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, R.; Su, X. Environmental beliefs and pro-environmental behavioral intention of an environmentally themed exhibition audience: The mediation role of exhibition attachment. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211027966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becherer, R.C.; Richard, L.M. Self-monitoring as a moderating variable in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 1978, 5, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milin, P.; Hadzic, O. Moderating and mediating variables in psychological research. Anxiety 2011, 15, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. A multi-dimensional measure of environmental behavior: Exploring the predictive power of connectedness to nature, ecological worldview and environmental concern. Social Indicators Research 2019, 143, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S. Intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behaviour. Nature Climate Change 2015, 5, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L.; Cheung, C.T.Y. Why do young people do things for the environment? The effect of perceived values on pro-environmental behaviour. Young Consumers 2022, 23, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, P. (Ed.) Handbook of Arts-Based Research. Guilford Publications. 2017.

- Babin, B.J.; Zikmund, W.G. Exploring Marketing Research. Cengage Learning. 2015.

- Awang, Z.; Afthanorhan, A.; Mamat, M. The Likert scale analysis using parametric based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Computational Methods in Social Sciences 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, W.S. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. International Journal of Epidemiology 2009, 38, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozali, I. The structural equation model-concepts and applications with the Amos Program 24, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesa. 2017.

- Horn, S.D.; Horn, R.A.; Duncan, D.B. Estimating heteroscedastic variances in linear models. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1975, 70, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.Z. Multiple Regression and Beyond: An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling. Routledge. 2014.

- Pearl, J. The causal mediation formula: A guide to the assessment of pathways and mechanisms. Prevention Science 2012, 13, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Koo, J. The impact of social interaction and team member exchange on sport event volunteer management. Sport Management Review 2016, 19, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.E.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis (8th edition). Cengage Learning EMEA, United Kingdom. 2019.

- Lee, C.W. The success of biotech new ventures when combined with strategic alliances. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development 2007, 4, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Dash, S.; Malhotra, N.K. The impact of marketing activities on service brand equity: The mediating role of evoked experience. European Journal of Marketing 2018, 52, 596–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Cheah, J.H.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Moderation analysis: issues and guidelines. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2019, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelloway, E.K. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling: a researcher's guide; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.W. Strategic alliances influence on small and medium firm performance. Journal of Business Research 2007, 60, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Powell, R.B.; Ardoin, N.M. What difference does it make? Assessing outcomes from participation in a residential environmental education program. Journal of Environmental Education 2008, 39, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; Walker, L.M. Toward a grounded theory for residential environmental education: A case study of the New Jersey School of Conservation. Journal of Environmental Education 2005, 37, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Moser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. , traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.-I.; Chen, J.-Y. A model of green consumption behavior constructed by the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Market. Stud 2014, 2014. 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The importance of environmental knowledge for private and public sphere pro-environmental behavior: Modifying the value-belief-norm theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).