Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

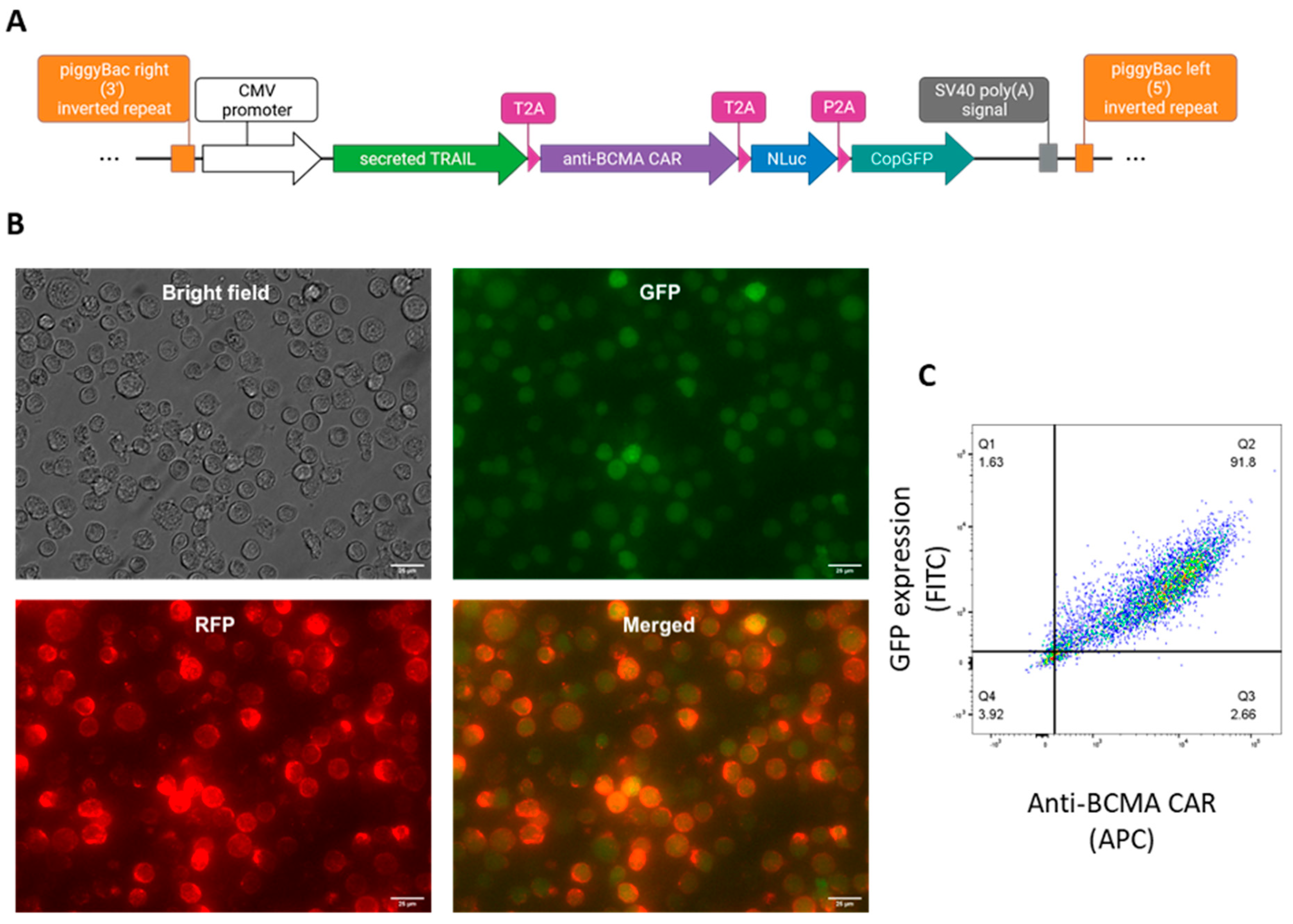

2.1. Generation of anti-BCMA CAR-NK92 cell line expressing sTRAIL

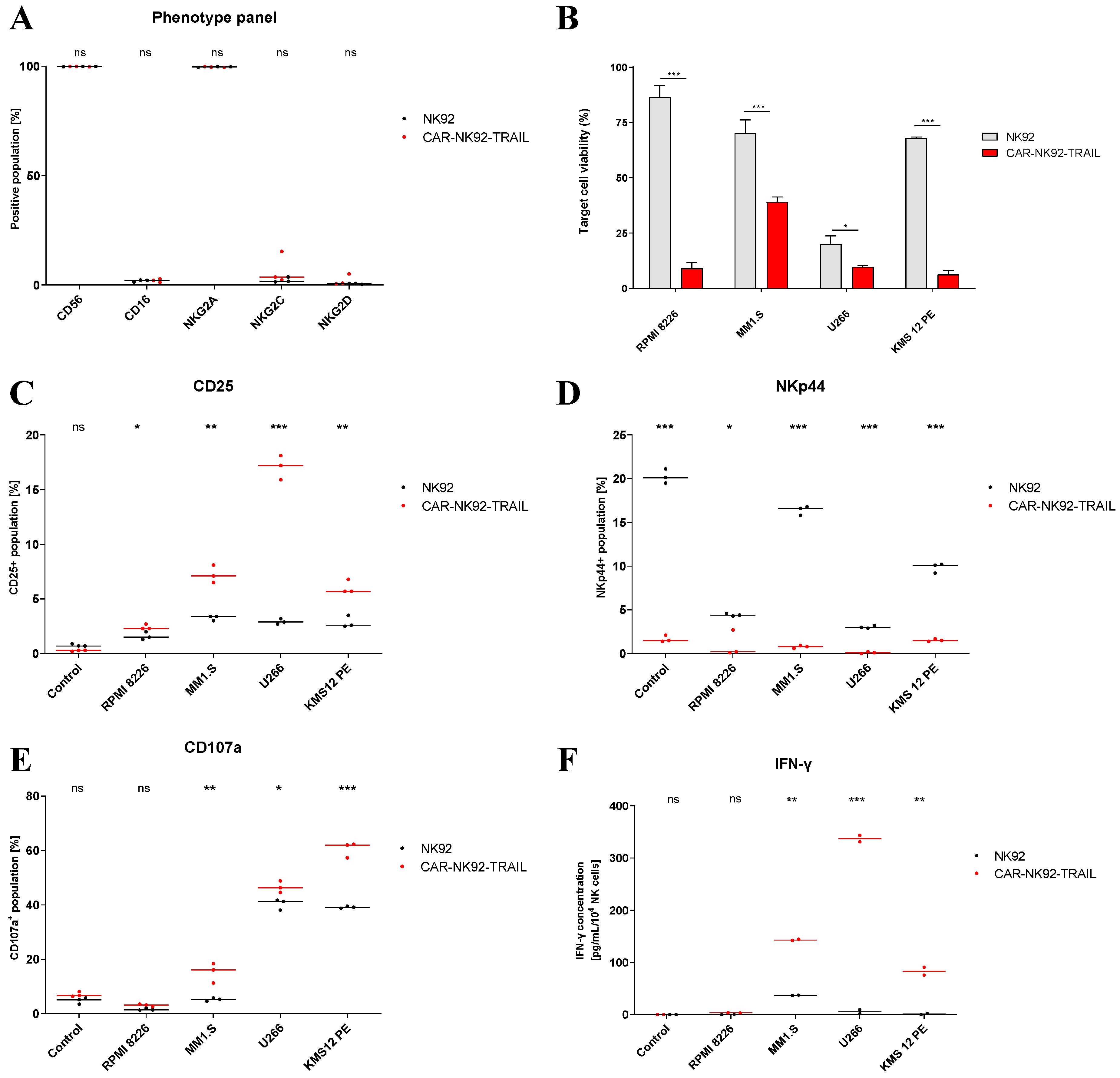

2.2. Phenotype and functional analysis of the CAR-NK92-TRAIL cell line

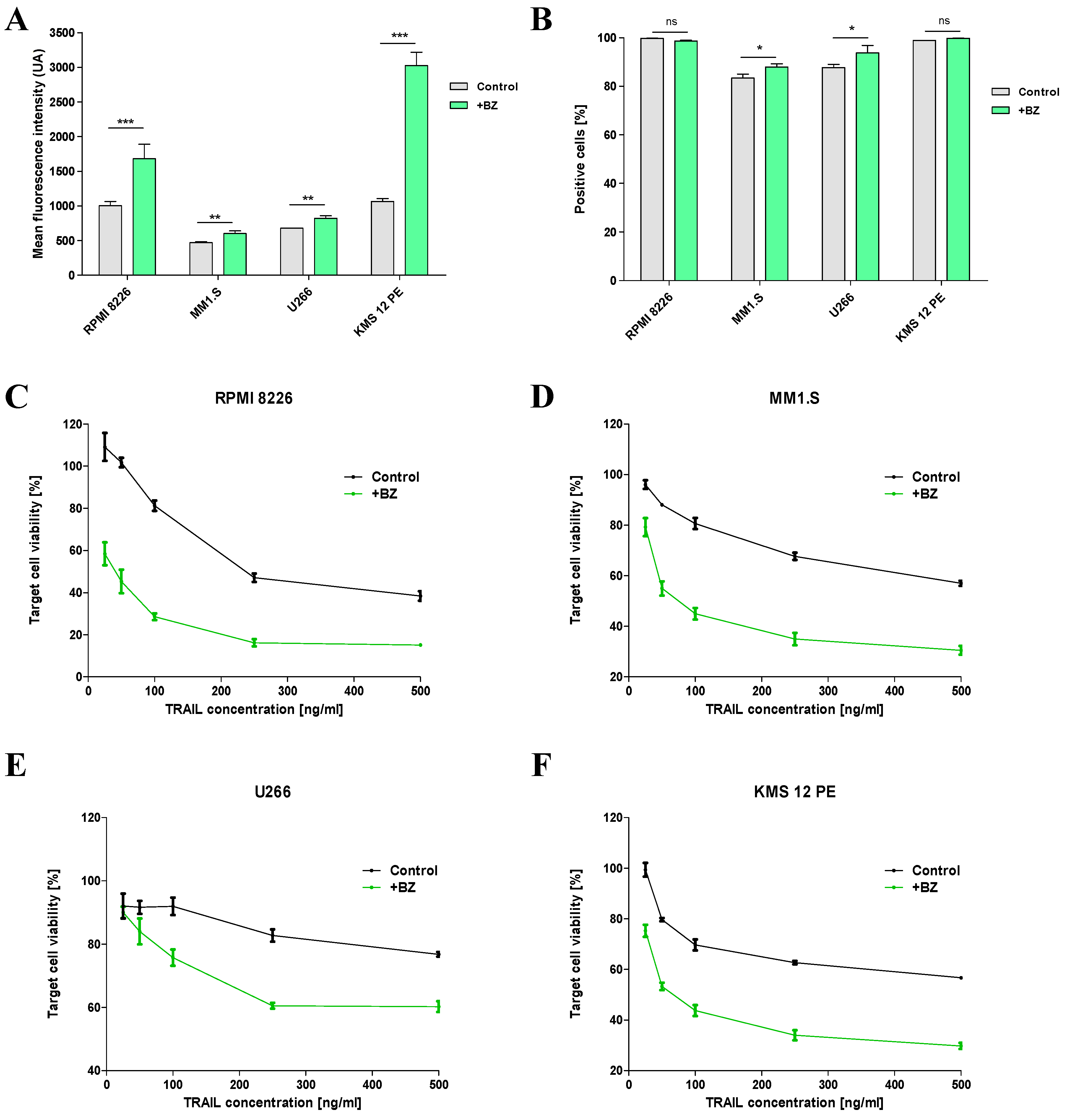

2.3. Sensitization of MM cells to TRAIL by BZ

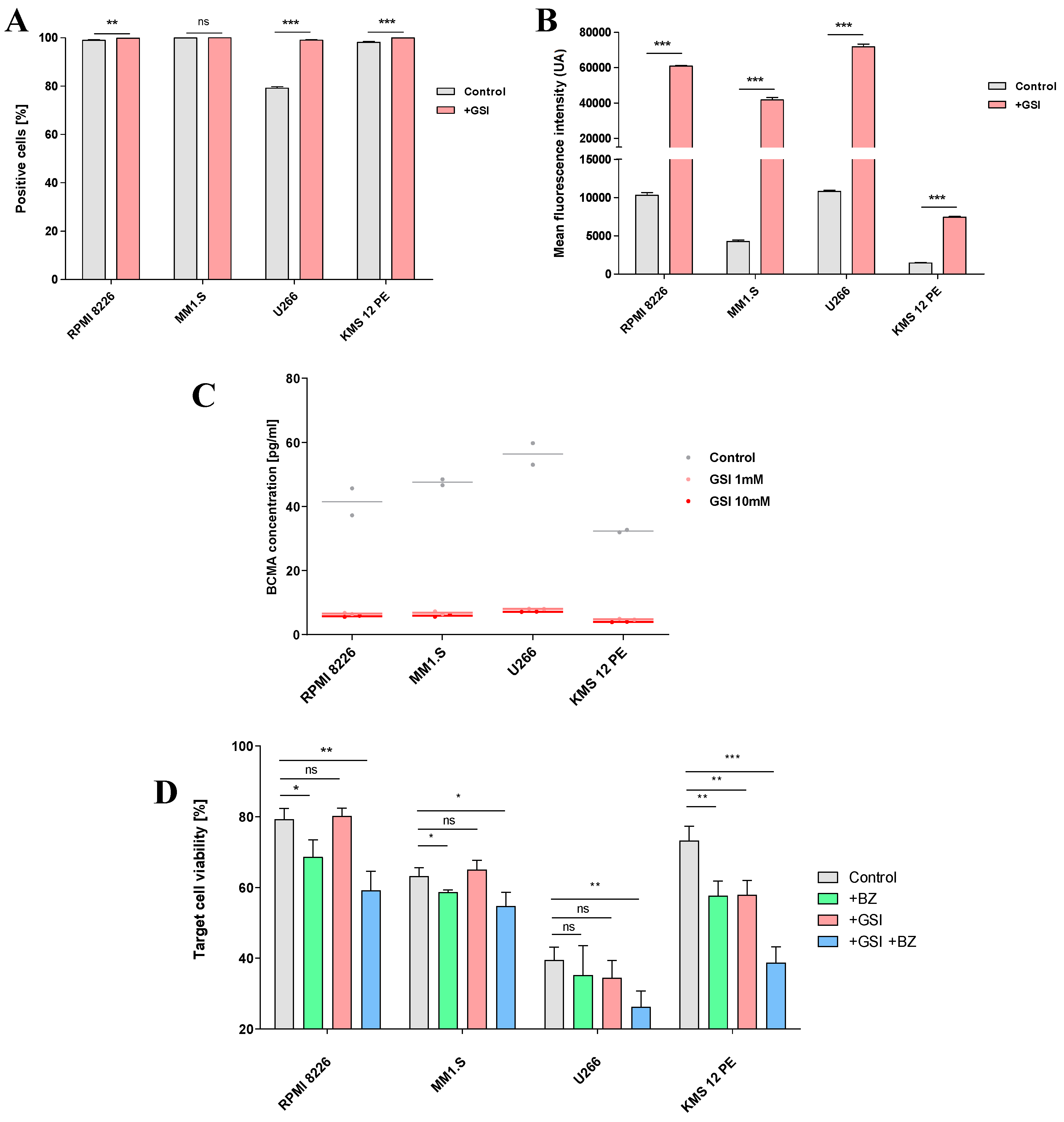

2.4. Combination treatment with GSI

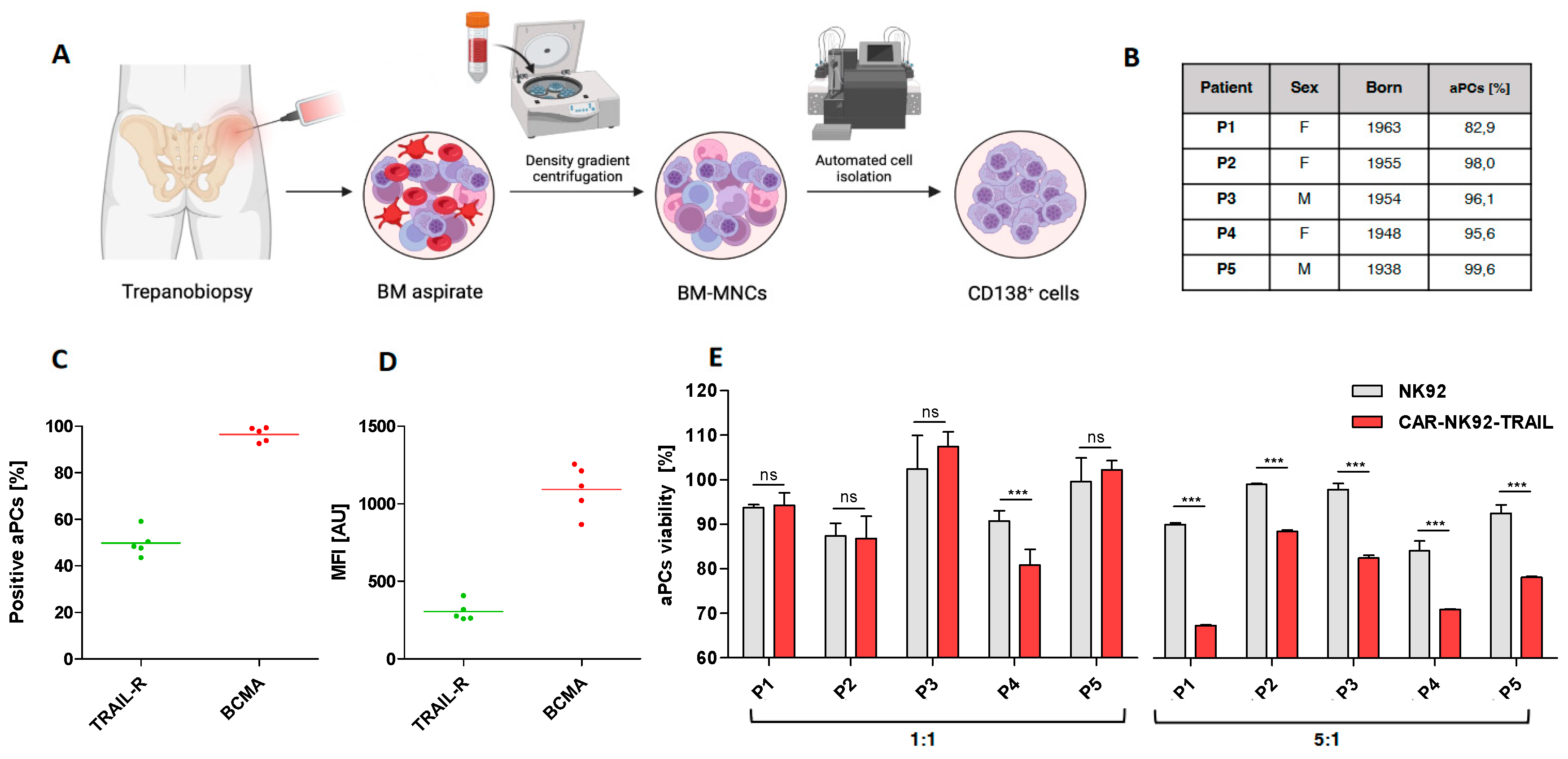

2.5. Efficiency of the engineered CAR-NK92-TRAIL against primary myeloma cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.1.1. Culture conditions

4.1.2. Cell treatments

4.2. Plasmid constructs

4.2.1. Lentiviral plasmids

4.2.2. Expression plasmids

4.3. Gene engineering

4.3.1. Lentiviral transduction of cancer cells

4.3.2. Electroporation of NK-92

4.4. Flow cytometry analyses

4.4.1. Assessment of the purity of CAR-NK92-TRAIL

4.4.2. Phenotype panel analysis

4.4.3. Functional panel analysis

4.5. Cytotoxic assays

4.5.1. Cytotoxic assays on MM cell lines

4.5.2. Cytotoxic assays on patient samples

4.6. Quantification of protein by ELISA

4.6.1. Quantification of shed BCMA from MM cells

4.6.2. Quantification of IFN-γ secretion by CAR-NK92-TRAIL

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| (a)PCs | (aberrant) Plasma cells |

| (c)DNA | (complementary) Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| (s)TRAIL | (secreted) Tumor-necrosis-factor related apoptosis inducing ligand |

| ADCC | Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| APC | Allophycocyanin |

| B2M | β2 microglobulin |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BZ | Bortezomib |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| CRS | Cytokine release syndrom |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| E:T | Effector to target ratio |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EMD | Extramedullary disease |

| FACS | Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| Fluc | Firefly luciferase |

| GC | Glucocorticoid |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GMP | Good manufacturing practices |

| GS(I) | Gamma-secretase (inhibitor) |

| GvHD | Graft versus host disease |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IMiDs | Immunomodulatory drugs |

| IRES | Internal ribosome entry site |

| LTR | Long terminal repeat |

| mAbs | Monoclonal antibodies |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| MGUS | Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance |

| MHC-I | class-I major histocompatibility complex |

| (S)MM | (Smoldering) Multiple Myeloma |

| mRNA | (messenger) Ribonucleic acid |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| Nluc | Nanoluc luciferase |

| P/S | Penicillin/streptomycin |

| PI | Proteasome inhibitor |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| wt | wild type |

References

- Nakaya, A.; Fujita, S.; Satake, A.; Nakanishi, T.; Azuma, Y.; Tsubokura, Y.; Hotta, M.; Yoshimura, H.; Ishii, K.; Ito, T.; et al. Impact of CRAB Symptoms in Survival of Patients with Symptomatic Myeloma in Novel Agent Era. Hematol. Rep. 2017, 9, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, R.; Rakshit, S.; Kumar, S. Extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Xu, B.; Chu, H.; Kourelis, T.; Go, R.S.; Wang, M.L.; Bachanova, V.; Wang, Y. Bortezomib-based consolidation or maintenance therapy for multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punke, A.P.; Waddell, J.A.; Solimando, J.D.A. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone (RVD) Regimen for Multiple Myeloma. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 52, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, H.; Ritchie, D.; Stewart, A.K.; Neeson, P.; Harrison, S.; Smyth, M.J.; Prince, H.M. Mechanism of action of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDS) in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2009, 24, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervoëlen, C.; Ménoret, E.; Gomez-Bougie, P.; Bataille, R.; Godon, C.; Marionneau-Lambot, S.; Moreau, P.; Pellat-Deceunynck, C.; Amiot, M. Dexamethasone-induced cell death is restricted to specific molecular subgroups of multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 26922–26934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, N.K.; Dwiwedi, P.; Charan, J.; Kaur, R.; Sidhu, P.; Chugh, V.K. Monoclonal Antibodies: A Review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 13, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, M.; Laroye, C.; Bensoussan, D.; Boura, C.; Decot, V. Natural Killer cells and monoclonal antibodies: Two partners for successful antibody dependent cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2021, 160, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudhikarn, K.; Wills, B.; Lesokhin, A.M. Monoclonal antibodies in multiple myeloma: Current and emerging targets and mechanisms of action. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2020, 33, 101143–101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Culos, K.; Roddy, J.; Shaw, J.R.; Bachmeier, C.; Shigle, T.L.; Mahmoudjafari, Z. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Efficacy, Toxicity, and Best Practices for Outpatient Administration. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2021, 27, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengsayadeth, S.; Savani, B.N.; Oluwole, O.; Dholaria, B. Overview of approved CAR-T therapies, ongoing clinical trials, and its impact on clinical practice. eJHaem 2021, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Cho, J.-Y. Recent Advances in Allogeneic CAR-T Cells. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, P.J.; Chng, W.J. CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma: more room for improvement. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munshi, N.C.; Anderson, L.D., Jr.; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanber K, Savani B, Jain T. Graft-versus-host disease risk after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: the diametric opposition of T cells. Br J Haematol. 2021, 195, 660–668. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Huang, H.; Cheng, H.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Characteristics and Risk Factors of Cytokine Release Syndrome in Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.S.; Stroncek, D.F.; Ren, J.; Eder, A.F.; West, K.A.; Fry, T.J.; Lee, D.W.; Mackall, C.L.; Conry-Cantilena, C. Autologous lymphapheresis for the production of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, J.N.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 2016, 127, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakekolathu, J.; Rutella, S. T-Cell Manipulation Strategies to Prevent Graft-Versus-Host Disease in Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplantation. Biomedicines 2017, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargett, T.; Brown, M.P. The inducible caspase-9 suicide gene system as a "safety switch" to limit on-target, off-tumor toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, V.; Schleinitz, N.; Brunet, C.; Ravet, S.; Bonnet, E.; Lafarge, X.; Touinssi, M.; Reviron, D.; Viallard, J.F.; Moreau, J.F.; et al. Comparative analysis of NK cell subset distribution in normal and lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocyte conditions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Lal, G. The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Killer Cells Function and Its Importance in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1124–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskoboinik, I.; Whisstock, J.C.; Trapani, J.A. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.; Dong, H.; Liang, Y.; Ham, J.D.; Rizwan, R.; Chen, J. CAR-NK cells: A promising cellular immunotherapy for cancer. EBioMedicine 2020, 59, 102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wallace, D.L.; De Lara, C.M.; Ghattas, H.; Asquith, B.; Worth, A.; Griffin, G.E.; Taylor, G.P.; Tough, D.F.; Beverley, P.C.; et al. In vivo kinetics of human natural killer cells: the effects of ageing and acute and chronic viral infection. Immunology 2007, 121, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.; Trinklein, N.D.; Buelow, B.; Patterson, G.H.; Ojha, N.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Author Correction: Anti-BCMA chimeric antigen receptors with fully human heavy-chain-only antigen recognition domains. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsten, M.; Namazi, A.; Reger, R.; Levy, E.; Berg, M.; Hilaire, C.S.; Childs, R.W. Bortezomib sensitizes multiple myeloma to NK cells via ER-stress-induced suppression of HLA-E and upregulation of DR5. OncoImmunology 2018, 8, e1534664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, D.; Milsom, M.D.; Shaffer, J.; Neuenfeldt, J.; Shaaban, A.F.; Margison, G.P.; Fairbairn, L.J.; Chinnasamy, N. Multicistronic lentiviral vectors containing the FMDV 2A cleavage factor demonstrate robust expression of encoded genes at limiting MOI. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomakina, G.Y.; Modestova, Y.A.; Ugarova, N.N. Bioluminescence assay for cell viability. Biochem. (Moscow) 2015, 80, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluchamy, J.P.; Delso-Vallejo, M.; Kok, N.; Bohme, F.; Seggewiss-Bernhardt, R.; van der Vliet, H.J.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Huppert, V.; Spanholtz, J. Standardized and flexible eight colour flow cytometry panels harmonized between different laboratories to study human NK cell phenotype and function. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Barlogie, B.; Berenson, J.; Singhal, S.; Jagannath, S.; Irwin, D.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Srkalovic, G.; Alsina, M.; Alexanian, R.; et al. A Phase 2 Study of Bortezomib in Relapsed, Refractory Myeloma. New Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manasanch, E.E.; Orlowski, R.Z. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Tung, C.-H.; Yang, K.; Weissleder, R.; Breakefield, X.O. Inducible Release of TRAIL Fusion Proteins from a Proapoptotic Form for Tumor Therapy. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 3236–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Chen, L.; Yan, D.; Dong, W.; Chen, M.; Niu, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Nie, X.; Fang, Y. Effectiveness and safety of anti-BCMA chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatment in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1149138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.A.; Hoffmann, F.S.; Kuhn, P.-H.; Cheng, Q.; Chu, Y.; Schmidt-Supprian, M.; Hauck, S.M.; Schuh, E.; Krumbholz, M.; Rübsamen, H.; et al. γ-secretase directly sheds the survival receptor BCMA from plasma cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pont, M.J.; Hill, T.; Cole, G.O.; Abbott, J.J.; Kelliher, J.; Salter, A.I.; Hudecek, M.; Comstock, M.L.; Rajan, A.; Patel, B.K.R.; et al. γ-Secretase inhibition increases efficacy of BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells in multiple myeloma. Blood 2019, 134, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, S.; Mariani, E.; Meneghetti, A.; Cattini, L.; Facchini, A. Calcein-Acetyoxymethyl Cytotoxicity Assay: Standardization of a Method Allowing Additional Analyses on Recovered Effector Cells and Supernatants. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001, 8, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadakis, G.F.; Spiliotopoulou, M. Investigating the Quality of Life for Cancer Patients and Estimating the Cost of Immunotherapy in Selected Cases. Cureus 2022, 14, e32390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subklewe, M.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Humpe, A. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells: A Race to Revolutionize Cancer Therapy. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2019, 46, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirot, L.; Philip, B.; Schiffer-Mannioui, C.; Le Clerre, D.; Chion-Sotinel, I.; Derniame, S.; Potrel, P.; Bas, C.; Lemaire, L.; Galetto, R.; et al. Multiplex Genome-Edited T-cell Manufacturing Platform for “Off-the-Shelf” Adoptive T-cell Immunotherapies. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 3853–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Fang, C.; Jiang, S.; June, C.H.; Zhao, Y. Multiplex Genome Editing to Generate Universal CAR T Cells Resistant to PD1 Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2255–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, K.P.; Hodge, J.W. The emerging role of off-the-shelf engineered natural killer cells in targeted cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2021, 23, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingemann, H.; Boissel, L.; Toneguzzo, F. Natural Killer Cells for Immunotherapy – Advantages of the NK-92 Cell Line over Blood NK Cells. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 91–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Diao, Y. Natural Killer Cells and Current Applications of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified NK-92 Cells in Tumor Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Bexte, T.; Gebel, V.; Kalensee, F.; Stolzenberg, E.; Hartmann, J.; Koehl, U.; Schambach, A.; Wels, W.S.; Modlich, U.; et al. High Cytotoxic Efficiency of Lentivirally and Alpharetrovirally Engineered CD19-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cells Against Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colamartino, A.B.L.; Lemieux, W.; Bifsha, P.; Nicoletti, S.; Chakravarti, N.; Sanz, J.; Roméro, H.; Selleri, S.; Béland, K.; Guiot, M.; et al. Efficient and Robust NK-Cell Transduction With Baboon Envelope Pseudotyped Lentivector. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Huls, H.; Kebriaei, P.; Cooper, L.J.N. A new approach to gene therapy usingSleeping Beautyto genetically modify clinical-grade T cells to target CD19. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 257, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Yoon, M.; Lee, J.-J.; Shin, M.-G.; Ryang, D.-W.; Kook, H.; Kim, S.-K.; Cho, D. Ex vivo expansion of natural killer cells using cryopreserved irradiated feeder cells. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Motais, B.; Charvátová, S.; Walek, Z.; Hrdinka, M.; Smolarczyk, R.; Cichoń, T.; Czapla, J.; Giebel, S.; Šimíček, M.; Jelínek, T.; et al. Selection, Expansion, and Unique Pretreatment of Allogeneic Human Natural Killer Cells with Anti-CD38 Monoclonal Antibody for Efficient Multiple Myeloma Treatment. Cells 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Loo, J.C.; Wright, J.F. Progress and challenges in viral vector manufacturing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 25, R42–R52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morellet, N.; Li, X.; A Wieninger, S.; Taylor, J.L.; Bischerour, J.; Moriau, S.; Lescop, E.; Bardiaux, B.; Mathy, N.; Assrir, N.; et al. Sequence-specific DNA binding activity of the cross-brace zinc finger motif of the piggyBac transposase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2660–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curio, S.; Jonsson, G.; Marinović, S. A summary of current NKG2D-based CAR clinical trials. Immunother. Adv. 2021, 1, ltab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wolterink, R.G.J.K.; Wang, J.; Bos, G.M.J.; Germeraad, W.T.V. Chimeric antigen receptor natural killer (CAR-NK) cell design and engineering for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samur, M.K.; Fulciniti, M.; Aktas Samur, A.; Bazarbachi, A.H.; Tai, Y.-T.; Prabhala, R.; Alonso, A.; Sperling, A.S.; Campbell, T.; Petrocca, F.; et al. Biallelic loss of BCMA as a resistance mechanism to CAR T cell therapy in a patient with multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimman, T.; Slomp, A.; Martens, A.; Grabherr, S.; Li, S.; van Diest, E.; Meeldijk, J.; Kuball, J.; Minnema, M.C.; Eldering, E.; et al. Serpin B9 controls tumor cell killing by CAR T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mel, S.; Lim, S.H.; Tung, M.L.; Chng, W.-J. Implications of Heterogeneity in Multiple Myeloma. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosicki, S.; Simonova, M.; Spicka, I.; Pour, L.; Kriachok, I.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Pylypenko, H.; Auner, H.W.; Leleu, X.; Doronin, V.; et al. Once-per-week selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus twice-per-week bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma (BOSTON): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, H.; Melear, J.; Faber, E.; Bensinger, W.I.; Burke, J.M.; Narang, M.; Stevens, D.; Gunawardena, S.; Lutska, Y.; Qi, K.; et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed and relapsed multiple myeloma: LYRA study. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 185, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusa, K.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.A.; Bradley, A.; Craig, N.L. A hyperactive piggyBac transposase for mammalian applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingegnere, T.; Mariotti, F.R.; Pelosi, A.; Quintarelli, C.; De Angelis, B.; Tumino, N.; Besi, F.; Cantoni, C.; Locatelli, F.; Vacca, P.; et al. Human CAR NK Cells: A New Non-viral Method Allowing High Efficient Transfection and Strong Tumor Cell Killing. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).