Introduction

Research methodology (RM) teaching is included in the curricula of all scientific disciplines. Its teaching is important for several reasons. First, RM teaches students to analyze and evaluate data and build logical arguments based on evidence, thereby promoting their ability to think critically (McKelvie & Standing, 2018). These skills are essential in any field of study and are highly valuable in the workplace. Second, it prepares students for graduate studies: Many students pursue graduate studies, where RM is an integral part of their coursework. By introducing RM at the undergraduate level, students are better prepared for the demands of graduate research (Madan & Teitge, 2013). Third, encourages evidence-based decision making: RM provides students with the skills to collect and analyze data, which is essential for making evidence-based decisions in a variety of settings, including academia, business, and government (Webber, 2013). Fourth, increases research productivity: By teaching RM, students are better equipped to conduct research, which can lead to increased research productivity and quality (Madan & Teitge, 2013). Fifth, RM teaches students to think creatively and innovatively, which is essential for solving complex problems and developing new ideas (Peachey & Baller, 2015).

Overall, teaching RM in undergraduate education encourages a culture of evidence-based decision making and innovation and supports the acquisition of essential skills for future careers.

Despite these advantages, teaching RM can be challenging. Undergraduate students often approach the course with a negative attitude because they are unaware of its benefits, their experience of learning the subject has been unfavorable, or both (Matos et al., 2023; Sizemore & Lewandowski, 2009).

The study of attitudes as a powerful predictor of behavior mediated by intentions is a well-established field of study (Conner & Sparks, 2015). Ajzen & Fishbein (2000) “use the term ‘attitude’ to refer to the evaluation of an object, concept, or behavior along a dimension of favor or disfavor, good or bad, like or dislike.” (p.3).

There is variability in the results of studies that have addressed the description of psychology undergraduate students' attitudes about science, psychology as a science, or the teaching of research methodology. While some report that students prefer activities requiring less commitment, effort, and initiative than the commonly available psychological research activities (e.g., listening or reading about research vs. helping to conduct it) (Vittengl et al., 2004). Others have found that undergraduates intentions to engage in research-related activities were most influenced by their attitudes toward research in their future career field. These attitudes were found to be more influential than their research activities and perceptions of the research environment (Griffioen, 2019). In addition, the fact that students do not recognize psychology as a science may be suggestive of their low regard for scientific inquiry (Holmes & Beins, 2009).

An underexplored topic is the relationship between attitudes toward research and the perceived experience in research methodology training. Recent qualitative research with Colombian university students revealed that they regarded RM as an annoying, unimportant, and easy-to-pass course. The study also identified the teacher's pedagogical practice and the curricular content of the course as the reasons for the negative perceptions (Álvarez Merlano et al., 2022).

Based on the hypothesis that a satisfactory experience with the course of RM will be associated with more positive attitudes toward research, and that knowledge gained through training will also be positively related to RM, this study examined these relationships in psychology students at a public university in Mexico City.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted between August and October 2022.

Participants

Using non-probabilistic sampling, students from different groups and semesters of a public school of psychology were invited to participate voluntarily in the study. As inclusion criteria, it was established that the participants had to be formally enrolled in some semester of the career or have less than six months of having completed their degree at the time of the measurement.

Variables

Research attitudes. The questionnaire "Attitude toward research in university students" (Barrios & Delgado, 2020). was utilized. The questionnaire consists of twenty-eight statements. Four constructs with seven items each were identified in the original version: research skills, positive appraisal, obstacles to research, and negative appraisal. The responses have a Likert scale format (0 = "strongly disagree"; 1 = "disagree"; 2 = "agree"; 3 = "strongly agree"). The authors reported a coefficient of internal consistency of 0.73 for the complete questionnaire.

Also, based on earlier work with psychology students at the university where the study was conducted (Montero, 2019), another scale of attitudes toward research with a semantic differential structure was also developed. It included a set of ten bipolar adjectives (Research is... interesting - boring, easy - difficult, etc.).

Experience in research methodology courses (ERMC): A 10-point analog scale (from 1 to 10) was used, where 1 equaled the "worst experience in research methodology courses" and 10 equaled the "best experience in research methodology courses".

As covariates, the following sociodemographic and academic performance variables were included: age, gender, subjects failed, Grade point average (in a range from 5 to 10), and semester enrollment.

Procedure

First, judges reviewed the instruments to ensure their face validity. Once corrected, all instruments were uploaded to a form hosted on the Google Forms site. A pilot test was carried out with ten students from the target population to discover potential mistakes in the instructions and form navigation.

Volunteer involvement of students was asked for recruitment purposes through classroom invitations and with the agreement of the professor in charge of the class. Participants used their cell phones to access the form using a QR code. Once on the form, individuals had to explicitly accept their participation through informed consent, in which their confidentiality and anonymity were assured and guaranteed, and those who agreed continued answering the instruments. All of them were thanked at the conclusion for their participation.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic and academic variables was performed. Quantitative variables were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion, and qualitative variables with frequencies and proportions. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the research attitude scale and an exploratory factor analysis of the attitude scale with semantic differential format were performed, respectiveley. The internal consistency of both scales was estimated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Likewise, the type of data distribution was identified using the Shapiro-Wilk test to decide the appropriate approach for the analyses (parametric or nonparametric). Correlations between the two attitude scales and research methodology experience were estimated. The scale scores were compared according to sex, semester, and whether a course had been failed. Finally, multivariate models were estimated, one for each attitude scale, with the experience with the research methodology as the independent variable and the sociodemographic and academic variables as covariables. A value of p < .05 was established as the significance criterion. All analyses were performed with Stata v. 17 software (StataCorp, 2021).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample. A total of 261 participants were recruited, mostly women (62%). No significant differences were observed in the distribution of participants by sex and semester, nor differences between sexes in age or in the percentage of failed students. Females had a slightly and significantly higher-grade point average (GPA) than males.

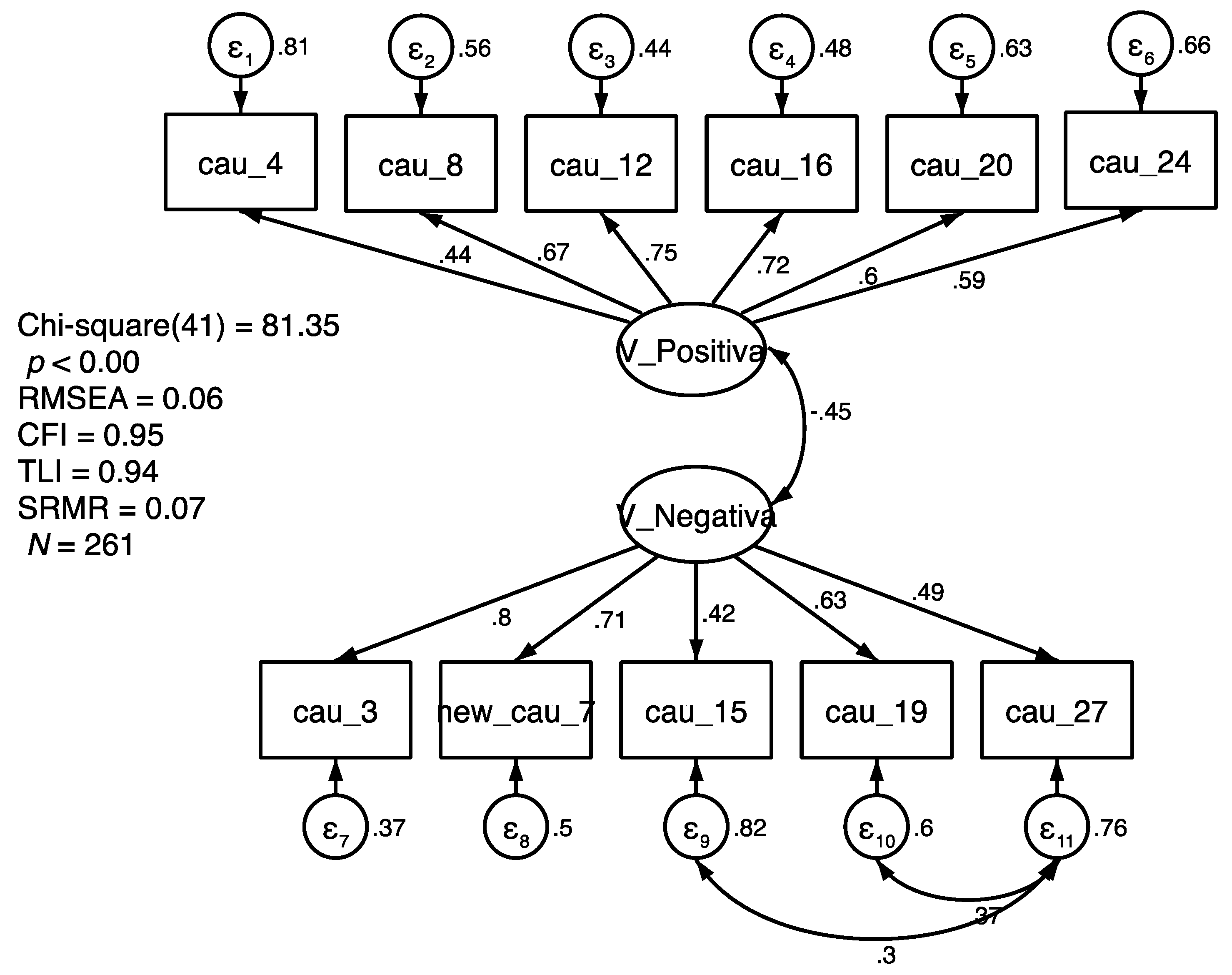

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire.

For the Semantic Differential attitude scale, the matrix determinant was equal to 0.034, Keiser-Meyer Olkin (0.80) and Bartlett's sphericity tests (χ

2=864.36, p < 0.05), which together showed that the exploratory factor analysis was feasible to perform. The AFE with oblique rotation identified three factors that explained 56.5% of the variance of the items.

Table 2 shows the factor loadings of the three factors and the corresponding items. Given that the complexity dimension had an internal consistency coefficient below what is usually recommended (Taber, 2018), it was excluded from subsequent analyses. For interpretation purposes, higher scores indicate a worse assessment of the importance of and interest in research.

Although some of the correlations had low coefficients, most study variables correlated significantly in the predicted directions. As expected, as students' experiences in research methodology courses improved, their attitudes toward research also improved. The correlations support the instruments' validity in general (

Table 3).

Except for the meaningless scale where a marginally significant difference (p = 0.05) was found between men and women (means 6.5 and 5.3, respectively), no significant differences were found in the variables of positive appraisal, negative appraisal, meaningless, boring and ERMC, by sex, semester or having failed courses.

Multivariate analyses

Since the dependent variables did not have a normal distribution, it was decided to perform the regression analyses using a robust method. The four models were adjusted for sex, failing courses and GPA (

Table 4). In all four cases, perceived experience in research methodology courses was significantly associated with research attitudes. Clearly, as the appraisal of the experience improves, negative evaluations decrease, and positive evaluations increase.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between experience and knowledge acquired in RM courses and attitudes towards research in a sample of undergraduate psychology students from a public university in Mexico City.

The findings revealed a positive correlation between learning experiences in RM courses and positive attitudes toward RM. Similarly, negative associations between RM course experience and negative attitudes toward RM were found. These findings were independent of the participants' grade point average, failing courses, academic semester, or gender.

The results are consistent with the study of Landa-Blanco & Cortés Ramos (2021) who identified that regardless of academic degree, number of courses and research projects completed, GPA and gender, attitudes towards research were positively associated with satisfaction with research courses, which seems to indicate that it is the latter variable that is best associated with attitudes towards RM. This underscores the importance of learning experiences on student attitudes.

On the other hand, the results indicated that GPA was slightly and negatively associated with ERMC, but not with attitudes toward RM. In this regard, a study with undergraduate psychology students showed that after attending an RM and statistics course, students' knowledge improved, while their interest and attitudes about perceived usefulness decreased (Sizemore & Lewandowski, 2009). While in Freng's (2020) study, the GPA of students in advanced psychology courses was not associated with the number of RM courses completed, the perception of psychology as a scientific discipline, nor with perceived anxiety about RM which is consistent with the results of this report.

Clearly, the results show the importance of teaching in the development of students' research competencies, both in terms of knowledge and attitude, and confirm what has been described in other studies (e.g., Becerra et al., 2020; Hernandez et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2020) regarding the conflict between the importance of research training and how difficult and discouraging teaching it can be.

Typically, at the undergraduate level, RM is taught to introduce students with research methods and data processing so that they can develop their own research studies, i.e., to produce knowledge, which may impact the perceived disconnection of RM with practice and, consequently, negative attitudes about its usefulness and significance (Griffioen, 2019; Gurung & Stoa, 2020; Strohmetz et al., 2023). In contrast, when a teaching strategy is adopted that explicitly considers students' baseline knowledge, interests, attitudes, and anxiety toward RM, attitudes toward RM improve, and even more so when students are able to investigate topics of personal interest and apply course concepts in non-academic and professional contexts (Wishkoski et al., 2022).

Regarding the limitations of the study, although the instruments employed proved to be an adequate measure of attitudes, the omission of the complexity dimension in the semantic differential scale due to the identified reliability coefficients suggests the need to include more precise descriptors that facilitate the understanding of the perceived complexity of IM by students, as some studies report that difficulty is perceived as a barrier that is negatively associated with attitudes towards IM (Balloo, 2019; Kumar et al., 2020). In addition, it is conceivable that the sample size utilized affected the statistical power of the study, despite the consistency of the identified associations when employing robust statistical analysis methods and controlling for multiple variables.

Conclusions

Effective training in RM is significant in the formation of empirical epistemic thinking, as opposed to intuitive thinking, which is more likely to promote practices without scientific basis (Gaudiano et al., 2011; Landa-Blanco & Cortés-Ramos, 2021; Nussbaumer-Streit et al., 2022).

Students' experiences in research methodology courses appear to affect their attitudes toward research and, consequently, the likelihood of incorporating it into their professional practice following academic training. Research in this area with appropriate designs is warranted.

An approach to teaching RM at the undergraduate level that is based more on the promotion of evidence-based practice than on the production and execution of research projects, which are almost always limited in scope and manufacture, appears to be a potential area of research, with implications for the transformation of teaching strategies and contents.

References

- Acock, A. C. (2013). Discovering structural equation modeling using Stata (1st ed). Stata Press.

- Ajzen, I. , & Fishbein, M. (2000). Attitudes and the Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. European Review of Social Psychology, 11(1), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Merlano, N. , Rodelo Mercado, A. J., & Duncan Pajaro, Y. (2022). Percepción de los estudiantes universitarios colombianos sobre la asignatura de Metodología de la Investigación. Fronteras en Ciencias de la Educación, 1(2), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Balloo, K. (2019). Students’ Difficulties During Research Methods Training Acting as Potential Barriers to Their Development of Scientific Thinking. In M. Murtonen & K. Balloo (Eds.), Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education (pp. 107–137). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E. , & Delgado, U. (2020). Diseño y validación del cuestionario “Actitud hacia la investigación en estudiantes universitarios.” Revista Innova Educación, 2(2). Directory of Open Access Journals. [CrossRef]

- Becerra, J. , Contreras, M., Mercado, A., Servin, A., & Valencia, G. (2020). Módulo de Fundamentos Metodológico-Instrumentales: Opinión de los estudiantes. In M. Contreras (Ed.), Formación del Psicólogo, de las Funciones a las Competencias Profesionales. (pp. 26–55). UNAM, FES Zaragoza.

- Conner, M. , & Sparks, P. (2015). The theory of planned behaviour and the reasoned action approach. In Predicting and changing health behaviour. Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models (3rd ed., pp. 143–188). Open University Press.

- Freng, S. (2020). Predicting Performance in Upper Division Psychology Classes: Are Enrollment Timing and Performance in Statistics and Research Methods Important? Teaching of Psychology, 47(1), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Gaudiano, B. A. , Brown, L. A., & Miller, I. W. (2011). Let your intuition be your guide? Individual differences in the evidence-based practice attitudes of psychotherapists. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(4), 628–634. [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, D. M. E. (2019). The influence of undergraduate students’ research attitudes on their intentions for research usage in their future professional practice. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(2), 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Gurung, R. A. R. , & Stoa, R. (2020). A National Survey of Teaching and Learning Research Methods: Important Concepts and Faculty and Student Perspectives. Teaching of Psychology, 47(2), 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R. M. , Montes-Valer, E., Mamani-Benito, O., Ortega-Pauta, B. I., Saavedra-Lopez, M. A., & Calle-Ramirez, X. M. (2022). Index of Attitude towards Scientific Research in Peruvian Psychology Students. International Journal of Education and Practice, 10(2), 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. D. , & Beins, B. C. (2009). Psychology is a Science: At Least Some Students Think So. Teaching of Psychology, 36(1), 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C. , Geethanjali, A., Agil, S., Jyothi, C., Sasikala, P., & Chandrasekhar, V. (2020). Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Barriers of Research among Medical Students. National Journal of Research in Community Medicine, 9(1). http://journal.njrcmindia.com/index.

- Landa-Blanco, M. , & Cortés-Ramos, A. (2021). Psychology students’ attitudes towards research: The role of critical thinking, epistemic orientation, and satisfaction with research courses. Heliyon, 7(12), e08504–e08504. [CrossRef]

- Madan, C. , & Teitge, B. (2013). The Benefits of Undergraduate Research: The Student’s Perspective. The Mentor: Innovative Scholarship on Academic Advising, 15. [CrossRef]

- Matos, J. F. , Piedade, J., Freitas, A., Pedro, N., Dorotea, N., Pedro, A., & Galego, C. (2023). Teaching and Learning Research Methodologies in Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences, 13(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, S. , & Standing, L. G. (2018). Teaching Psychology Research Methodology Across the Curriculum to Promote Undergraduate Publication: An Eight-Course Structure and Two Helpful Practices. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018. 0229. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, G. (2019). Experiencias en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de la Metodología de la Investigación en estudiantes de psicología de pregrado: Análisis de grupos focales [Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza]. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2019/julio/0791746/Index.

- Nussbaumer-Streit, B. , Jesser, A., Humer, E., Barke, A., Doering, B. K., Haid, B., Schimböck, W., Reisinger, A., Gasser, M., Eichberger-Heckmann, H., Stippl, P., Gartlehner, G., Pieh, C., & Probst, T. (2022). A web-survey assessed attitudes toward evidence-based practice among psychotherapists in Austria. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9374–9374. [CrossRef]

- Peachey, A. A., & Baller. Ideas and Approaches for Teaching Undergraduate Research Methods in the Health Sciences. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 2015, 27(3), 434–442. [Google Scholar]

- Sizemore, O. J. , & Lewandowski, G. W. (2009). Learning Might Not Equal Liking: Research Methods Course Changes Knowledge but Not Attitudes. Teaching of Psychology, 36(2), 90–95. [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata Statistical Software (Version 17). StataCorp LLC.

- Strohmetz, D. B. , Ciarocco, N. J., & Lewandowski, G. W. (2023). Why am I here? Student perceptions of the research methods course. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. [CrossRef]

- Vittengl, J. R. , Bosley, C. Y., Brescia, S. A., Eckardt, E. A., Neidig, J. M., Shelver, K. S., & Sapenoff, L. A. (2004). Why are Some Undergraduates More (and others Less) Interested in Psychological Research? Teaching of Psychology, 31(2), 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Webber, M. (2013). Developing Advanced Practitioners in Mental Health Social Work: Pedagogical Considerations. Social Work Education, 32(7), 944–955. [CrossRef]

- Wishkoski, R., Meter. Wishkoski, R., Meter, D. J., Tulane, S., King, M. Q., Butler, K., & Woodland, L. A. Student attitudes toward research in an undergraduate social science research methods course. Higher Education Pedagogies 2022, 7(1), 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).