Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study setting & participants

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion

2.3. Procedure

- Instruments

- World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL) Group, 1998). [9]

- Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) [27]

- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [40]

- Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) [41]

- Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale (AASE) [42]

- NIMHANS neuro-psychological Battery for Cognitive Functions [43]

- Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) [44]

- The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [45]

2.5. Statistical analysis

2.6. Sample size

2.6. Ethical approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Bryazka, D.; Reitsma, M.B.; Griswold, M.G.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, Z.; Abdoli, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdullah, A.Y.M.; et al. Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020. Lancet 2022, 400, 185–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators: Alcohol use and burden for195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis forthe Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2016, 392, 1015–1035.

- Hagman, B.T.; Falk, D.; Litten, R.; Koob, G.F. Defining Recovery From Alcohol Use Disorder: Development of an NIAAA Research Definition. Am. J. Psychiatry 2022, 179, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.F.; Greene, M.C.; Bergman, B.G. Beyond abstinence: changes inindices of quality of life with time in recovery in a nationally rep-resentative sample of US adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2018, 42, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudet, A.B. The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2011, 6, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirouac, M.; Stein, E.R.; Pearson, M.R.; Witkiewitz, K. Viability of the World Health Organization quality of life measure to assess changes in quality of life following treatment for alcohol use disorder. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.; Scott, C. Managing Addiction as a Chronic Condition. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pr. 2007, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group WHOQOL. (1997). Measuring quality of life. Geneva: The World Health Organization, 1–13.

- Donovan, D.; E Mattson, M.; A Cisler, R.; Longabaugh, R.; Zweben, A. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. J. Stud. Alcohol, Suppl. 2005, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; Cantor, S.B.; Steinbauer, J.R.; et al. Alcohol use disorders, consumption patterns, and health-related quality of life of primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1997, 21, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpaert, K.; De Maeyer, J.; Broekaert, E.; et al. Impact of addiction severity and psychiatric comorbidity on the quality of life of alcohol-, drug-and dual-dependent persons in residential treatment. Eur Addict Res 2012, 19, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.B.; Dawson, D.A.; Smith, S.M.; Grant, B.F. Antisocial behavioral syndromes and 3-year quality-of-life outcomes in United States adults. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012, 126, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.Y.; Landron, F.; Lehert, P. for the New European AlcoholismTreatment Study Group. Improvement in quality of life after treatment for alcohol dependence with acamprosate and psychosocialsupport. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004, 28, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlon, H.A.; Hurlocker, M.C.; Witkiewitz, K. Mechanisms of quality-of-life improvement in treatment for alcohol use disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 90, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Grant, J.E. Relationship between quality of life in young adults and impulsivity/compulsivity✰. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahbairi, N.; Laniepce, A.; Segobin, S.; Cabé, N.; Boudehent, C.; Vabret, F.; Rauchs, G.; Pitel, A.-L. Determinants of health-related quality of life in recently detoxified patients with severe alcohol use disorder. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olickal, J.J.; Saya, G.K.; Selvaraj, R.; Chinnakali, P. Association of alcohol use with quality of life (QoL): A community based study from Puducherry, India. Clin. Epidemiology Glob. Heal. 2021, 10, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, D.; Enewoldsen, N.; Weisel, K.K.; Fuhrmann, L.; Lang, C.; Saur, S.; Berking, M.; Zink, M.; Ahnert, A.; Falkai, P.; et al. Association of impulsivity with quality of life and well-being after alcohol withdrawal treatment. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCastro, J.S.; Youngblood, M.; Cisler, R.A.; Mattson, M.E.; Zweben, A.; Anton, R.F.; Donovan, D.M. Alcohol Treatment Effects on Secondary Nondrinking Outcomes and Quality of Life: The COMBINE Study. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeppen, J.-B.; Faouzi, M.; Sanchez, N.; Rahhali, N.; Bineau, S.; Bertholet, N. Quality of Life Depends on the Drinking Pattern in Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014, 49, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkiewitz, K.; Kranzler, H.R.; Hallgren, K.A.; O'Malley, S.S.; Falk, D.E.; Litten, R.Z.; Hasin, D.S.; Mann, K.F.; Anton, R.F. Drinking Risk Level Reductions Associated with Improvements in Physical Health and Quality of Life Among Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 2453–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisciandaro, J.J.; DeSantis, S.M.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Simultaneous Modeling of the Impact of Treatments on Alcohol Consumption and Quality of Life in the COMBINE Study: A Coupled Hidden Markov Analysis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, F.G.; Barratt, E.S.; Dougherty, D.M.; Schmitz, J.M.; Swann, A.C. Psychiatric Aspects of Impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broos, N.; Schmaal, L.; Wiskerke, J.; Kostelijk, L.; Lam, T.; Stoop, N.; Weierink, L.; Ham, J.; de Geus, E.J.C.; Schoffelmeer, A.N.M.; et al. The Relationship between Impulsive Choice and Impulsive Action: A Cross-Species Translational Study. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e36781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.M.; Critchley, H.D.; Duka, T. The role of emotions and physiological arousal in modulating impulsive behaviour. Biol Psychol 2018, 133, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, J.H.; Stanford, M.S.; Barratt, E.S. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol 1995, 51, 768–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.P.; Lynam, D.R. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Ketzenberger, K.; Forrest, L. Impulsiveness and compulsiveness in alcoholics and nonalcoholics. Addict. Behav. 2007, 25, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Diemen, L.; Bassani, D.G.; Fuchs, S.C.; Szobot, C.M.; Pechansky, F. Impulsivity, age of first alcohol use and substance use disorders among male adolescents: a population based case–control study. Addiction 2008, 103, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Z.W.; Kaiser, A.J.; Lynam, D.R.; Charnigo, R.J.; Milich, R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskunpinar, A.; Dir, A.L.; Cyders, M.A. Multidimensionality in Impulsivity and Alcohol Use: A Meta-Analysis Using the UPPS Model of Impulsivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, R.A.; Alhassoon, O.M.; Allen, K.E.; Wollman, S.C.; Hall, M.; Thomas, W.J.; Gamboa, J.M.; Kimmel, C.; Stern, M.; Sari, C.; et al. Meta-analyses of clinical neuropsychological tests of executive dysfunction and impulsivity in alcohol use disorder. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2016, 43, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol 2009, 14, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, I.; Demeter, I.; Janka, Z.; Demetrovics, Z.; Maraz, A.; Andó, B. Different aspects of impulsivity in chronic alcohol use disorder with and without comorbid problem gambling. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, J.D.; Ashenhurst, J.R.; Cervantes, M.C.; Groman, S.M.; James, A.S.; Pennington, Z.T. Dissecting impulsivity and its relationships to drug addictions. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2015, 1327, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, A.; Bonsu, J.A.; Charnigo, R.J.; Milich, R.; Lynam, D.R. Impulsive Personality and Alcohol Use: Bidirectional Relations Over One Year. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2016, 77, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliedrecht, W.; Roozen, H.G.; Witkiewitz, K.; de Waart, R.; Dom, G. The Association Between Impulsivity and Relapse in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder: A Literature Review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021, 56, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershberger, A.R.; Um, M.; Cyders, M.A. The relationship between the UPPS-P impulsive personality traits and substance use psychotherapy outcomes: A meta -analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 178, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.F.; De La Fuente, J.R.; Grant, M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, R.F. Obsessive–compulsive aspects of craving: development of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Addiction. 2000, 95, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Carbonari, J.P.; Montgomery, RP.; Hughes, S.O. The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy scale. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1994, 55, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopukumar K., Rao Shobini L., Subbakrishna D. K.NIMHANS neuropsychology battery. National institute of mental Health and neuro sciences, Bangalore,2004.

- Hamilton, M. Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM-A). J Med. 1959, 61, 81–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)-17 items. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967, 6, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Bhatia, M. Quality of life as an outcome measure in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2013, 22, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Storr, C.L. Alcohol Use and Health-Related Quality of Life among Youth in Taiwan. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2006, 39, 752–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.M.; Rodríguez-Míguez, E. Using the SF-6D to measure the impact of alcohol dependence on health-related quality of life. Eur. J. Heal. Econ. 2015, 16, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, V.; Gomez, B.; Guo, S.; Low, Y.D.; Koh, P.K.; Wong, K.E. An Exploration of Quality of Life and its Predictors in Patients with Addictive Disorders: Gambling, Alcohol and Drugs. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 2012, 10, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmek, P.; Berlin, I.; Michel, L.; Berghout, C.; Meunier, N.; Aubin, H.-J. Determinants of improvement in quality of life of alcohol-dependent patients during an inpatient withdrawal programme. Int. J. Med Sci. 2009, 6, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, J.J.; Kushner, M.G. Co-Occurring Alcohol Use Disorder and Anxiety: Bridging Psychiatric, Psychological, and Neurobiological Perspectives. Alcohol Res. 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatcioglu, O.; Yapici, A.; Cakmak, D. Quality of life, depression and anxiety in alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 27, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.A.; Najman, J.M.; Plotnikova, M.; Clavarino, A.M. Quality of life, age of onset of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in adolescence and young adulthood: Findings from an Australian birth cohort. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015, 34, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon MAT, Sabari SOT, Srinivasan B. Correlation between age of alcohol dependence and quality of life—A hospital based cross sectional study. 2018 [cité 14 déc 2020]; Disponible sur: https://imsear.searo.who.int/jspui/handle/123456789/187032.

- Choi, S.W.; Na, R.H.; Kim, H.O.; Choi, S.B.; Choi, Y.S. The relationship between quality of life and psycho-socio-spiritual characteristics in male patients with alcohol dependence. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2006, 45, 459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.P.; Randall, C.L. Anxiety and alcohol use disorders: comorbidity and treatment considerations. Alcohol Res. 2012, 34, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flensborg-Madsen, T.; Mortensen, E.L.; Knop, J.; Becker, U.; Sher, L.; Grønbæk, M. Comorbidity and temporal ordering of alcohol use disorders and other psychiatric disorders: results from a Danish register-based study. Compr. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneier, F.R.; Foose, T.E.; Hasin, D.S.; Heimberg, R.G.; Liu, S.-M.; Grant, B.F.; Blanco, C. Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suasnabar, J.M.H.; Nadkarni, A.; Palafox, B. Determinants of alcohol use among young males in two Indian states: A population-based study. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2023, 28, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.H.; Hong, H.G.; Jeon, S.-M. Personality and alcohol use: The role of impulsivity. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, S.; Cimochowska, A.; Kornreich, C.; Hanak, C.; Verbanck, P.; Petit, G. Neurophysiological correlates of response inhibition predict relapse in detoxified alcoholic patients: some preliminary evidence from event-related potentials. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1025–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.V.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F.; Campos, V.R.; Abrantes, S.S.C.; Fuentes, D.; Bechara, A.; Correa, H. Neuropsychological assessment of impulsive behavior in abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Rev. Bras. de Psiquiatr. 2009, 31, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabé, N.; Lanièpce, A.; Pitel, A.L. Physical activity: A promising adjunctive treatment for severe alcohol use disorder. Addict. Behav. 2021, 113, 106667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.G.; Curado, D.F.; Opaleye, E.S.; Donate, A.P.G.; Scattone, V.V.; Noto, A.R. Impulsivity and Mindfulness among Inpatients with Alcohol Use Disorder. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-alcohol user healthy controls (n=44) | Alcohol Use Disorder (n=88) | |||

| Variable | N(%)/Mean (SD) | N(%)/Mean (SD) | P value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Education | School-educated | 14(31.82) | 38(43.2) | 0.207 |

| College-educated | 30 (68.18) | 50(56.8) | ||

| Type of family | Joint family | 30(68.18) | 48(54.4) | 0.133 |

| Nuclear Family | 14(31.3) | 40(45.5) | ||

| Employment status | Part-time Employed | 15(34.09) | 32(36.4) | 0.797 |

| Full-time Employed | 29(65.90) | 56(63.6) | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 11(25.0) | 28(31.8) | 0.338 |

| Married | 33(75.0) | 60(68.2) | ||

| Age at assessmnet | Age(yrs) | 36.06(9.80) | 37.55(8.31) | 0.387 |

| Quality of life domains | ||||

| QOL Physical health | 78.25(14.18) | 59.93(16.74) | <0.001 | |

| QOL Psychological | 75.56(13.45) | 50.75(18.93) | <0.001 | |

| QOL Social Relationships | 77.00(16.75) | 64.39(27.78) | 0.002 | |

| QOL Environment | 75.88(14.21) | 74.77(17.44) | 0.507 | |

| BIS -11 dimensions and total score | ||||

| BIS-11 Attention | 8.69(2.09) | 10.48 (3.29) | <0.001 | |

| BIS-11 Cognitive Instability | 6.23(2.31) | 6.70(2.03) | 0.225 | |

| BIS-11 Motor | 16.15(2.85) | 18.09(3.38) | <0.001 | |

| BIS-11 Perseverance | 6.38(1.44) | 7.95(2.47) | <0.001 | |

| BIS-11 Self-Control | 9.69(1.84) | 12.27(3.45) | <0.001 | |

| BIS-11 Cognitive Complexity | 12.69(2.42) | 14.07(2.43) | 0.003 | |

| BIS-11 Total | 59.84(6.90) | 68.43(8.79) | <0.001 | |

| Total sample 88 |

QOL Physical Health |

QOL Psychological Health |

QOL Social Relationship |

QOL Environment |

||||||||||

| Variables | n(%) | Mean | (SD) | p | Mean | (SD) | p | Mean | (SD) | p | Mean | (SD) | p | |

| Age (mean) | 37.55(8.31) | 59.53 | 16.74 | 0.269* | 50.75 | 18.93 | 0.708* | 64.39 | 27.78 | 0.465* | 74.77 | 17.44 | 0.151* | |

| Education | School Educated | 38(43.2) | 60.79 | (19.49) | 0.771 | 53.42 | 21.08 | 0.421 | 66.79 | 30.02 | 0.623 | 75.84 | 17.75 | 0.727 |

| College Educated | 50(56.8) | 59.28 | (14.70) | 48.72 | 17.28 | 62.56 | 26.44 | 73.96 | 17.53 | |||||

| Employment Status | Unemployed | 32(36.4) | 56.81 | (17.93) | 0.356 | 49.82 | 19.58 | 0.672 | 63.38 | 35.213 | 0.858 | 74.81 | 16.794 | 0.991 |

| Employed | 56(63.6) | 61.71 | (16.09) | 52.38 | 18.24 | 64.96 | 23.232 | 74.75 | 18.112 | |||||

| Type of family | Joint Family | 40(45.5) | 61.65 | (16.46) | 0.541 | 50.80 | 17.79 | 0.987 | 65.35 | 18.79 | 0.837 | 77.05 | 19.86 | 0.436 |

| Nuclear Family | 48(54.5) | 58.50 | (17.11) | 50.71 | 20.14 | 63.58 | 33.91 | 72.88 | 15.32 | |||||

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 28(31.8) | 52.86 | 17.77 | 0.055 | 41.64 | 16.02 | 0.028 | 47.29 | 27.15 | 0.004 | 69.43 | 19.79 | 0.168 |

| Married | 60(63.6) | 63.23 | 15.45 | 55.00 | 18.91 | 72.37 | 24.64 | 77.27 | 15.98 | |||||

| N | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| 1 | QOL Physical Health | 88 | 59.93 | 16.74 | - | ||||||||||

| 2 | QOL Psychological | 88 | 50.75 | 18.93 | .551** | - | |||||||||

| 3 | QOL Social Relationships | 88 | 64.39 | 27.78 | .314* | .346* | - | ||||||||

| 4 | QOL Environment | 88 | 74.77 | 17.44 | .651** | .438** | 0.264 | - | |||||||

| 5 | BIS Attention | 88 | 10.48 | 3.29 | -.655** | -.441* | -.372* | -.547** | - | ||||||

| 6 | BIS Cognitive Instability | 88 | 6.70 | 2.03 | -0.239 | -0.113 | -0.204 | -0.075 | 0.213 | - | |||||

| 7 | BIS Motor | 88 | 18.09 | 3.38 | -0.145 | -0.148 | -0.025 | -0.062 | 0.325* | 0.237 | - | ||||

| 8 | BIS Perseverance | 88 | 7.95 | 2.47 | 0.161 | 0.201 | -0.255 | 0.047 | -0.029 | 0.275 | 0.039 | - | |||

| 9 | BIS Self-control | 88 | 12.27 | 3.45 | -.343* | -.406* | -0.144 | -.462** | .497** | 0.042 | .310* | -0.083 | - | ||

| 10 | BIS Cognitive Complexity | 88 | 14.07 | 2.43 | 0.106 | -0.109 | 0.219 | 0.165 | -0.140 | 0.018 | 0.104 | 0.074 | 0.081 | - | |

| 11 | BIS Total Score | 88 | 68.43 | 8.79 | -.402** | -360* | -0.245 | -.369* | .661** | ..459** | .682** | .305* | .685** | .295 | - |

| 12 | HAM D score | 88 | 3.02 | 3.40 | -.527** | -.433** | -.388** | -.595** | .504** | 0.045 | 0.088 | -0.074 | .347* | -0.124 | 0.310* |

| 13 | HAM A score | 88 | 6.45 | 5.10 | -.658** | -.485** | -.317* | -.637** | .475* | .054 | 0.089 | -0.226 | .255 | -.062 | .239 |

| 14 | AUDIT Total scores | 88 | 31.52 | 5.47 | -0.269 | -.325* | -0.270 | 0.025 | .299* | 0.266 | 0.252 | 0.093 | -0.142 | -0.073 | 0.202 |

| 15 | OCDS Total scores | 88 | 7.80 | 11.40 | -0.229 | -0.171 | -0.142 | -.388** | 0.318* | -0.296 | 0.170 | -0.079 | 0.284 | -0.096 | 0.180 |

| 16 | Age of onset of alcohol use | 88 | 20.11 | 5.33 | 0.083 | 0.029 | 0.083 | 0.129 | -0.126 | -0.042 | -0.007 | -0.198 | -0.123 | -0.201 | -0.191 |

| 17 | Age | 88 | 37.55 | 8.31 | 0.170 | 0.058 | -0.113 | 0.220 | -0.113 | 0.070 | 0.274 | -0.042 | -0.169 | -0.179 | -0.066 |

| 18 | Duration of alcohol use | 88 | 12.77 | 8.04 | -0.001 | -0.114 | -0.173 | -0.087 | .114 | 0.184 | 0.182 | 0.011 | 0.128 | -0.113 | 0.147 |

| 19 | AASE (C)Total | 88 | 58.75 | 19.74 | 0.281 | .345* | 0.285 | .436** | -.476* | -0.023 | -0.218 | -0.075 | -.444** | 0.127 | -.390* |

| 20 | RAVLT Total | 88 | 45.59 | 7.23 | -0.135 | 0.066 | -0.015 | -0.191 | 0.321* | -0.005 | 0.014 | 0.193 | 0.242 | -0.022 | 0.245 |

| 21 | RAVLT IR | 88 | 9.73 | 2.35 | -0.189 | -0.206 | 0.051 | -0.223 | 0.239 | -0.149 | -0.227 | 0.085 | 0.129 | -0.013 | 0.031 |

| 22 | RAVLT DR | 88 | 10.00 | 2.27 | -0.055 | -0.010 | -0.037 | -0.022 | 0.177 | -0.066 | -0.175 | 0.194 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.038 |

| 23 | N 2 BACK Hits | 88 | 6.25 | 1.33 | -0.142 | -0.154 | 0.080 | -0.261 | 0.189 | 0.011 | 0.026 | -0.060 | -0.147 | 0.081 | .034 |

| 24 | N 2 BACK Error | 88 | 3.75 | 1.54 | 0.125 | 0.144 | -0.225 | 0.194 | 0.040 | -0.098 | -0.062 | -0.149 | 0.105 | -0.218 | -0.115 |

| 25 | CFT Copy | 88 | 34.15 | 2.87 | 0.016 | -0.227 | -0.072 | 0.000 | 0.102 | -0.193 | -0.112 | 0.039 | 0.037 | -0.022 | -0.040 |

| 26 | CFT IR | 88 | 19.64 | 6.31 | 0.046 | 0.117 | -0.074 | -0.021 | 0.024 | 0.026 | -0.248 | 0.000 | -0.022 | -0.175 | -0.149 |

| 27 | CFT DR | 88 | 18.78 | 6.38 | 0.118 | 0.189 | -0.073 | 0.030 | -.035 | -0.048 | -0.196 | 0.004 | -0.120 | -0.236 | -0.221 |

| 28 | DSST TT | 88 | 310.20 | 112.41 | 0.016 | 0.144 | 0.240 | -0.183 | -0.073 | -0.153 | 0.116 | 0.028 | -0.088 | 0.053 | -0.034 |

| 29 | ANT Total | 88 | 11.73 | 3.07 | 0.097 | 0.207 | .211 | 0.244 | -.026 | 0.035 | 0.005 | 0.069 | -0.050 | 0.180 | 0.048 |

| 30 | Stroop Effect | 88 | 153.63 | 78.80 | -0.147 | -.046 | 0.100 | -.105 | .202 | -0.292 | 0.145 | -0.144 | 0.057 | 0.142 | 0.093 |

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | |||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| Linear regression results for physical health domain | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 92.111 | 7.021 | 77.9 | 106.31 | <0.001 | |||||

| BIS Attention | -3.327 | 0.593 | -4.523 | -2.131 | <0.001 | -2.272 | 0.672 | -3.631 | -0.912 | 0.002 |

| BIS Self-control | -1.664 | 0.703 | -3.082 | -0.246 | 0.023 | -0.101 | 0.582 | -1.278 | 1.076 | 0.863 |

| HAM D Total Score | -2.589 | 0.645 | -3.890 | -1.288 | <0.00 | -0.393 | 0.796 | -1.217 | 2.003 | 0.624 |

| HAM-A Total Score | -2.160 | 0.381 | -2.928 | -1.391 | <0.001 | -1.642 | 0.517 | -2.687 | -0.597 | 0.003 |

| R2/Adjusted R2 | .587/.545 | |||||||||

| Liner regression results for Psychological domain | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 116.30 | 17.95 | 79.94 | 152.65 | <0.001 | |||||

| BIS Attention | -2.533 | 0.796 | -4.139 | -0.927 | 0.003 | -0.083 | 0.991 | -2.165 | 3.058 | 0.731 |

| BIS Self-control | -2.227 | 0.773 | -3.788 | -0.667 | 0.006 | -1.941 | 0.851 | -3.663 | -0.219 | 0.028 |

| HAM D Total Scores | -2.404 | 0.773 | -3.965 | -0.844 | 0.003 | -0.188 | 1.091 | -2.397 | 2.021 | 0.864 |

| HAM A Total Score | -1.798 | 0.501 | -2.808 | -0.788 | 0.001 | -1.112 | 0.711 | -2.551 | 0.327 | 0.126 |

| AUDIT Total Scores | -1.125 | 0.505 | -2.144 | -0.105 | 0.031 | -1.053 | 0.485 | -2.551 | -0.071 | 0.036 |

| R2/Adjusted R2 | .409/.331 | |||||||||

| Linear regression results for social relationships domain | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 51.526 | 22.038 | 6.95 | 96.101 | 0.025 | |||||

| BIS Attention | -3.137 | 1.208 | -5.574 | -0.700 | 0.013 | -1.332 | 1.389 | -4.142 | 1.478 | 0.344 |

| HAM D Total scores | -3.165 | 1.160 | -5.506 | -0.824 | 0.009 | -1.903 | 1.737 | -5.415 | 1.609 | 0.280 |

| HAM A Total scores | -1.728 | 0.796 | -3.335 | -0.121 | 0.036 | 0.123 | 1.138 | -2.178 | 2.424 | 0.914 |

| Marital Status | 25.081 | 8.236 | 8.460 | 41.702 | 0.004 | 18.1 | 8.772 | 0.457 | 35.742 | 0.045 |

| R2/adjusted R2 | 0.273/.198 | |||||||||

| Linear regression results for Environment domain | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 104.098 | 14.901 | 73.906 | 14.291 | <0.001 | |||||

| BIS attention | -2.896 | 0.684 | -4.276 | -1.516 | <0.001 | -0.877 | 0.779 | -2.455 | 0.701 | 0.267 |

| BIS self-regulation | -2.333 | 0.691 | -3.729 | -0.938 | 0.002 | -1.041 | 0.678 | -2.414 | 0.332 | 0.133 |

| HAM D Total scores | -3.046 | 0.635 | -4.328 | -1.764 | <0.001 | -0.475 | 0.93 | -2.359 | 1.409 | 0.612 |

| HAM-A Total scores | -2.178 | 0.406 | -2.998 | -1.358 | <0.001 | -1.36 | 0.586 | -2.547 | 0.172 | 0.123 |

| OCDS Total scores | -0.594 | 0.218 | -1.033 | -0.155 | 0.009 | -0.09 | 0.225 | -0.545 | 0.336 | 0.692 |

| AASE Total scores | 0.385 | 0.123 | 0.137 | 0.633 | 0.003 | 0.046 | 0.14 | -0.239 | 0.33 | 0.748 |

| R2/adjusted R2 | 0.540/0.465 | |||||||||

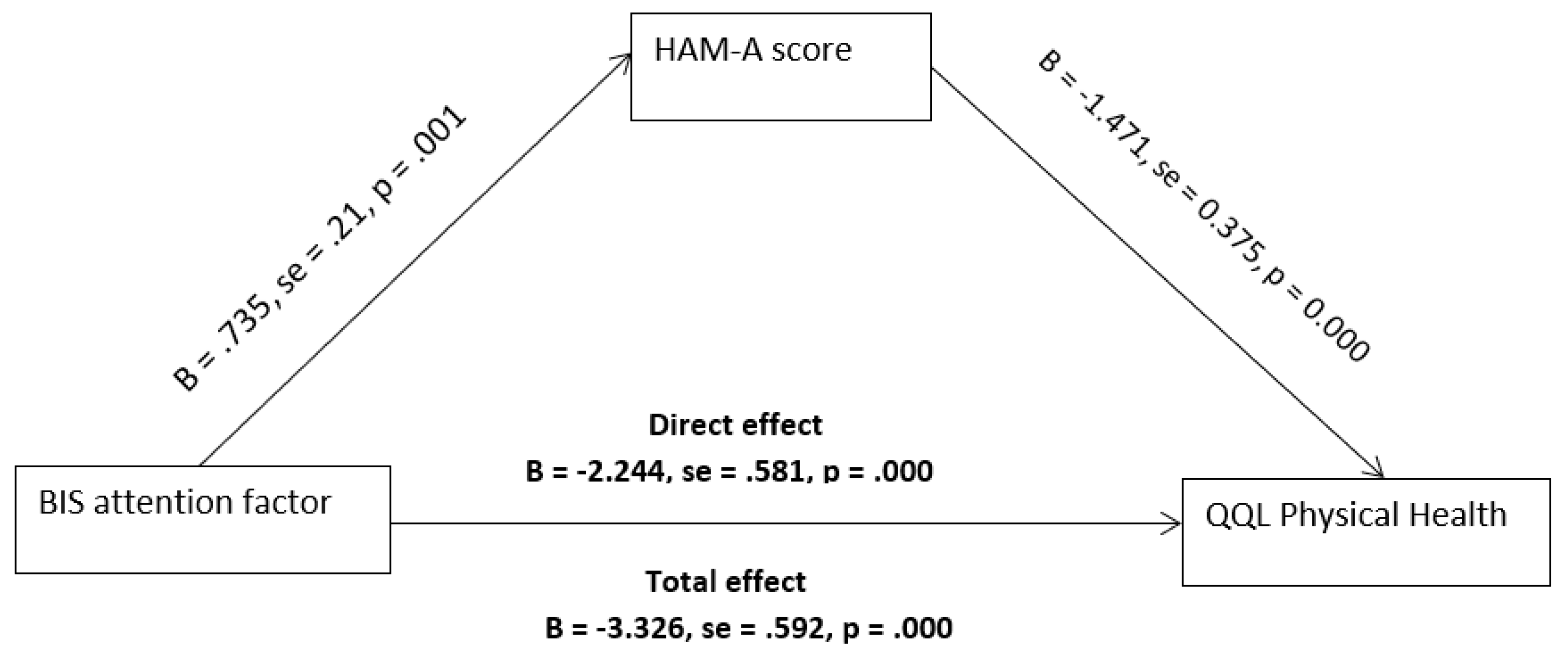

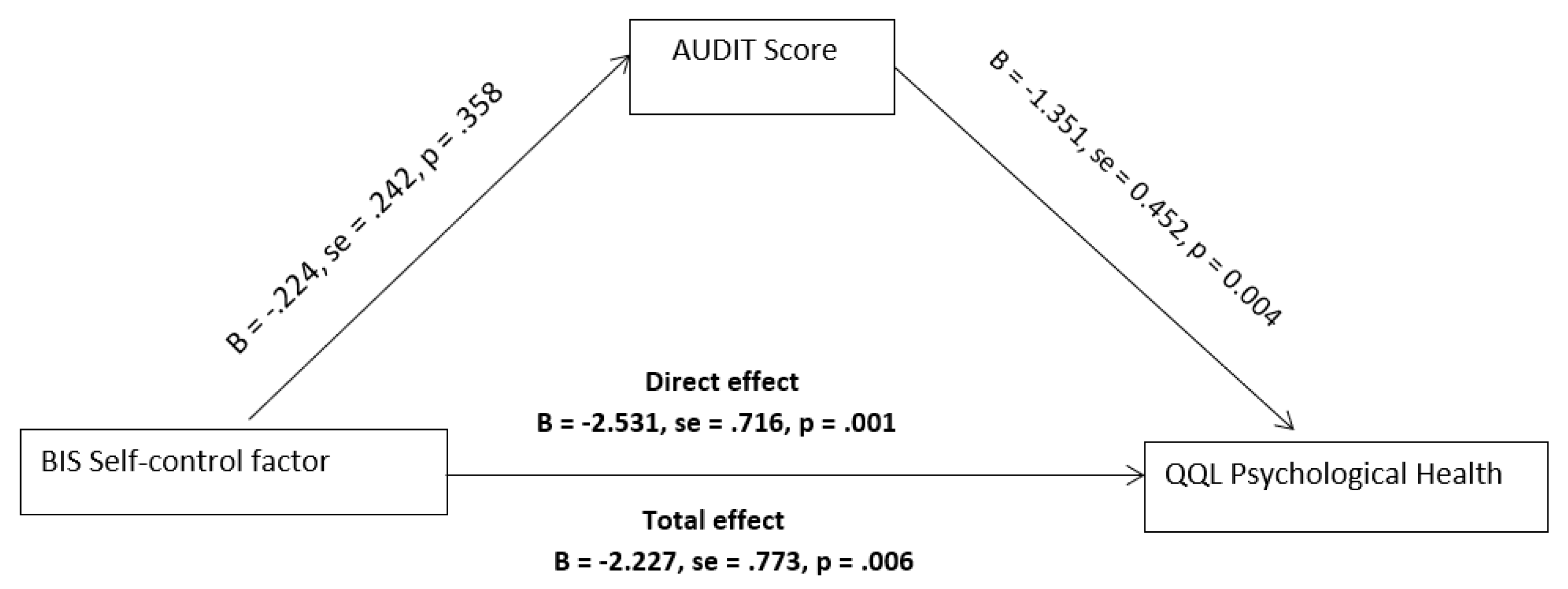

| Relationship | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | 95% CI | Conclusion | |

| LL | UL | |||||

| BIS attention -> HAM-A score -> QOL Physical Health domain | -3.326 | -2.244 | -1.082 | -2.008 | -0.3598 | Partial mediation |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| BIS Self-control -> AUDIT score -> QOL Psychological domain | -2.227 | -2.531 | .303 | -.273 | .900 | No Mediation |

| P value | .006 | .001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).