Introduction

To communicate optimally with horses, bits are used in equestrian sports. However, there is no bit that is equally accepted by every horse and liked by every rider. To ensure fair play at national competitions, the German Equestrian Federation (FN) is responsible for the allowed bits. Similarly, at the international level, the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) is responsible for the rules and regulations for the protection of the health and well-being of horses during international competitions (FEI, 2023). The equipment catalog of the German Equestrian Federation (LPO) specifies that only materials that can withstand appropriate tension and which contours cannot be destroyed by the horse's chewing are permitted. Additionally, the materials must not be harmful to the horse's health, so metal, rubber, plastic, and leather are permitted (Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung e.V., n.d.). Only metals and plastics are allowed for double bridles and snaffles, and various materials can be combined. The pressure exerted by the bit can be used to communicate with the horse but can also cause discomfort or pain to the horse, particularly when bits are used incorrectly or in wrong sizes or types for the individual horse's mouth (Luke et al., 2023). Concerns regarding the welfare of horses in relation to the use of bits include mouth injuries, pain or discomfort, and impairments of the horse's ability to breathe or swallow properly (Uldahl & Clayton, 2019). In equestrian sports, there have long been a variety of opinions and views on how bits should be used to optimize both the horse's welfare and communication between rider and horse. While some argue that bits are necessary to give the rider the necessary control over the horse, others argue that bits can be uncomfortable or even painful for the horse and that there are better alternatives. Regardless of personal beliefs, factors must be considered when using bits to ensure that the horse's welfare is not compromised. This includes careful selection of the right bit type and material, the correct fit of the bit in the horse's mouth, and proper handling and application of the bit by the rider. It is important to note that the use of bits in horses can not only have an immediate impact on the horse's well-being, but can also have long-term effects (Cook, 1999). The use of bits that cause pain or discomfort can lead to the horse becoming unwilling to accept the bit and refusing to wear it in the future. This can not only lead to problems during training but also to a lack of control over the horse, which can endanger the rider's safety (Luke et al., 2023). When a bit is introduced into the horse's mouth, it rests on the tongue and can exert pressure on the palate, lips, and corners of the horse's mouth. Depending on the type of bit and rider's hand, this pressure can be exerted to varying degrees and for different lengths of time. If the pressure is excessive or the bit is used improperly, it can cause discomfort or pain to the horse, leading to a defensive reaction such as head shaking, opening of the mouth, or leaning on the bit. Even sharp bits that are not used incorrectly but may not be suitable for the individual horse can cause these reactions.

The aim of this article was to investigate different bits and the riders' opinions on the use of bits and the actual differences in the horse’s reaction and pain scale with different bits on shows. A total of 250 riders participated in the study and completed an online questionnaire that consisted of 15 questions. The questions covered topics such as the riders’ experience with bits, their understanding of the purpose of bits, and their opinions on the use of bits in different situations with their horses. To investigate the horse’s reactions on different bits, seven jumping competitions with a total of 540 videos were watched and evaluated by a rider and a veterinarian. A pain assessment was done to provide the most accurate analysis of animal pain.

Welfare

Animal welfare is often negatively defined, where well-being is seen as the absence of compromised welfare. This definition can be traced back to one of the earliest attempts to scientifically define well-being. In 1965, the Brambell Committee formulated the five freedoms, assuming that animal welfare is fulfilled when animals are free from:

Hunger, thirst, or insufficient nutrition,

Thermal and physical discomfort,

Injury or disease,

Fear and chronic stress,

As well as animals being free to exhibit normal, species-specific behavioral patterns.

Four out of these five freedoms were formulated based on the perspective that the absence of 'ill-being' implies the presence of well-being. However, these definitions and concepts often overlook the positive aspect of well-being (being well).

Recently, there have been attempts to approach well-being in a more positive manner. (Mench, 1998) suggests that the concept of well-being implies the presence of both positive and negative emotions, not just the absence of suffering. Also (Duncan, 2005), who states that "...well-being encompasses both positive and negative feelings, thus involving the satisfaction of desires and needs" aligns with Mench.

The latest advancement in animal welfare involves a significant progression by considering the animal's own perspective in welfare concepts. According to (Bracke et al. 1999) animal welfare is defined as the subjective experience of the animal, reflecting the quality of its life. These concepts take into consideration both scientific and societal understandings of animal consciousness, which now acknowledge that vertebrate, and partially invertebrate animals not only experience emotions in the moment but also relate them to their surroundings and experiences. Furthermore, they possess a certain degree of emotional adaptability (Ohl et al., 2008).The field of veterinary medicine takes a (patho)biological approach when considering the concept of animal welfare, which involves understanding the continuum between health and illness in relation to ethical values and norms, such as recognizing the intrinsic value of animals. In this context, the concept of well-being is seen as an internal state that is subjectively perceived as positive by the individual. Consequently, an individual experiencing a negative subjective state is considered to be in a state of non-well-being.

To define well-being, it is understood that an individual is in a state of well-being when it can actively adapt to its living conditions and achieve a positive state as perceived by the individual (Bracke et al., 1999).

Understanding the concept of animal welfare, particularly in the context of using bits in horses, is of paramount importance for this research study. By exploring various perspectives and definitions of animal welfare, it is possible to gain valuable insights into the factors that influence a horse's well-being and how it relates to their experiences and perceptions.

Taking a (patho)biological approach allows us to delve into the continuum between health and illness in horses, considering the ethical values and norms associated with their care. This perspective enables us to evaluate the impact of using bits on a horse's well-being by examining their physical and physiological responses, as well as their ability to adapt to their surroundings.

Incorporating the horse's own perception and subjective experience of well-being is a critical aspect. Recognizing that well-being encompasses more than just the absence of negative experiences, but also includes positive emotions and the fulfillment of desires and needs, is essential to our understanding. By taking the horse's subjective experience into account, we can gain deeper insights into how the use of bits may impact their overall well-being.

Furthermore, assessing the horse's adaptive capacity within the context of using bits is crucial. By examining how horses adapt to the presence of bits and identifying any potential limitations in their ability to adjust, we can better comprehend their welfare implications. Detecting behaviors that may indicate poor adaptation or negative experiences can provide valuable information about the potential effects of using bits on a horse's well-being.

Materials and Methods

1.1. Participants:

The study participants were 250 riders of all ages and experience levels, including both amateurs and professionals. Recruitment was conducted through a variety of channels, including social media platforms, equestrian forums, local riding clubs, and professional networks. Participants were asked to share the survey with their colleagues and equestrian networks to help ensure a diverse and representative sample.To participate in the study, participants were required to have experience riding horses and using bits. To ensure that the sample group was diverse and representative of the broader equestrian community, efforts were made to recruit participants with a range of experience levels and backgrounds. To make sure the riders were active in the past year, so they knew about the newest rules in equestrian sports, the participants were asked whether they had ridden a competition in the past 12 months and with how many horses they competed.

1.2. Survey tool:

The survey was designed to gather information on riders' preferences and use of bits. The survey consisted of 12 questions, including both open-ended and multiple-choice questions. The questions were designed to elicit information on why riders use certain bits, how they think about bits, and what factors influence their decision-making.

Some of the open-ended questions included prompts such as "Why do you prefer this particular bit?" and "What factors do you consider when selecting a bit for your horse?". The multiple-choice questions covered a range of topics, including the types of bits riders use, how they learned about different bits, and their opinions on various aspects of bit design and use.

The survey was pre-tested by a small group of riders to ensure clarity and ease of understanding. The questions were designed to allow for a wide range of responses and cover different aspects of bit use. The survey was conducted online, and participants were able to complete it at their convenience.

1.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The survey was conducted online. The data was collected anonymously and collated in an Excel spreadsheet. The results were evaluated quantitatively by calculating the frequencies and percentages of the different responses. The qualitative responses were subjected to a thematic analysis to identify the underlying motivations and practices of the respondents.

The survey was designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of riders' preferences and use of bits, including their reasons for choosing particular bits, their thoughts on different aspects of bit design and use, and the factors that influence their decision-making. The results of the survey were used to identify patterns and trends in riders' preferences and practices, and to gain insights into the reasons behind these patterns and trends.

Video Analyses

2.1. Study Design:

This study was designed to assess the prevalence of pain indicators in horses competing in seven events in Europe on the final day of the show. The study was conducted by a professional rider and a veterinarian who watched videos of the events and observed a total of 540 horses competing. The study utilized a pain assessment tool for ridden horses (ridden horse pain ethogram) based on the work of Dyson (2022), with some modifications. The riders' use of different bits was noted, as well as any observed expression of discomfort (head tilt, head shaking, ears behind the vertical, tail swishing etc.).

Shows included in the study:

Riesenbeck Finale CSI** March 27th, 2022

Z Tour CSI*** Zangersheide April 17th, 2022

CSI Deurne April 24th, 2022

Peelbergen CI**May 8th, 2022

CSI Madrid* May 15th, 2022

CSIO Rome May 29th, 2022

Knokke Hippique June 26th, 2022

Participants:

The study included 540 horses competing in seven outdoor and indoor CSI events in Europe. Regarding the horses observed in the videos, the distribution based on gender and birth year was as follows: 25% mares, 46% geldings, and 29% stallions born between 2000 and 2016.

To make sure the participants were on a similar level of experience only the grand prix was watched, so the riders had to qualify for this competition.

Pain Assessment Tool:

The pain assessment tool used in this study was based on the ridden horse pain ethogram invented by Dyson (2022). The tool was modified to include additional pain indicators observed in ridden horses, such as seeing a horse in cross canter for more than 5 strikes.

The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram, adapted from Dyson et al. 2022.

-

1.

Repeated changes of head position (up/down)

-

2.

Head tilted or tilting repeatedly (left/right)

-

3.

Ears rotated back behind vertical

-

4.

Mouth opening with separation of teeth, for > 10 s

-

5.

Bit pulled through the mouth

-

6.

Tongue exposed

-

7.

Tail swishing repeatedly (up/ down, side/ to side)

-

8.

Tempo must be reduced visibly several times (>1)

-

9.

Sudden change of direction, against rider’s cues

-

10.

Horse canters in cross canter for more than 5 strikes

-

11.

Reluctance to move forward (has to be kicked/ verbal encouragement)

Data Collection:

The professional rider and veterinarian watched the CSI events and observed the horses competing with different bits. The pain assessment tool was used to evaluate each horse's pain level during the competition.

Data Analysis:

The data collected during the study were entered into a database and analyzed using statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, including the prevalence of pain indicators, the type of bits used, the distribution of pain level, the differences between the sexes and many more.

Results

Questionnaire:

1.1. Participant Characteristics:

The study included a total of 250 riders who completed the survey. Of these, 30% (n=75) were professional showjumpers and 70% (n=175) were amateurs. In terms of competition experience, 12% (n=30) of riders had competed in less than 5 competitions, 20% (n=50) had competed in 5-10 competitions, and 68% (n=170) had competed in more than 10 competitions. Professional riders were significantly (<0.05) more likely to have competed in more than 10 competitions.

1.1. Number of Horses:

Most riders (54%, n=135) reported competing with 2-5 horses, while 26% (n=65) competed with only one horse and 20% (n=50) competed with more than 5 horses. Professional riders were significantly (<0.05) more likely to compete with more horses than amateurs.

Bit Use:

Most riders (92%, n=230) reported using different bits for different horses during competitions.

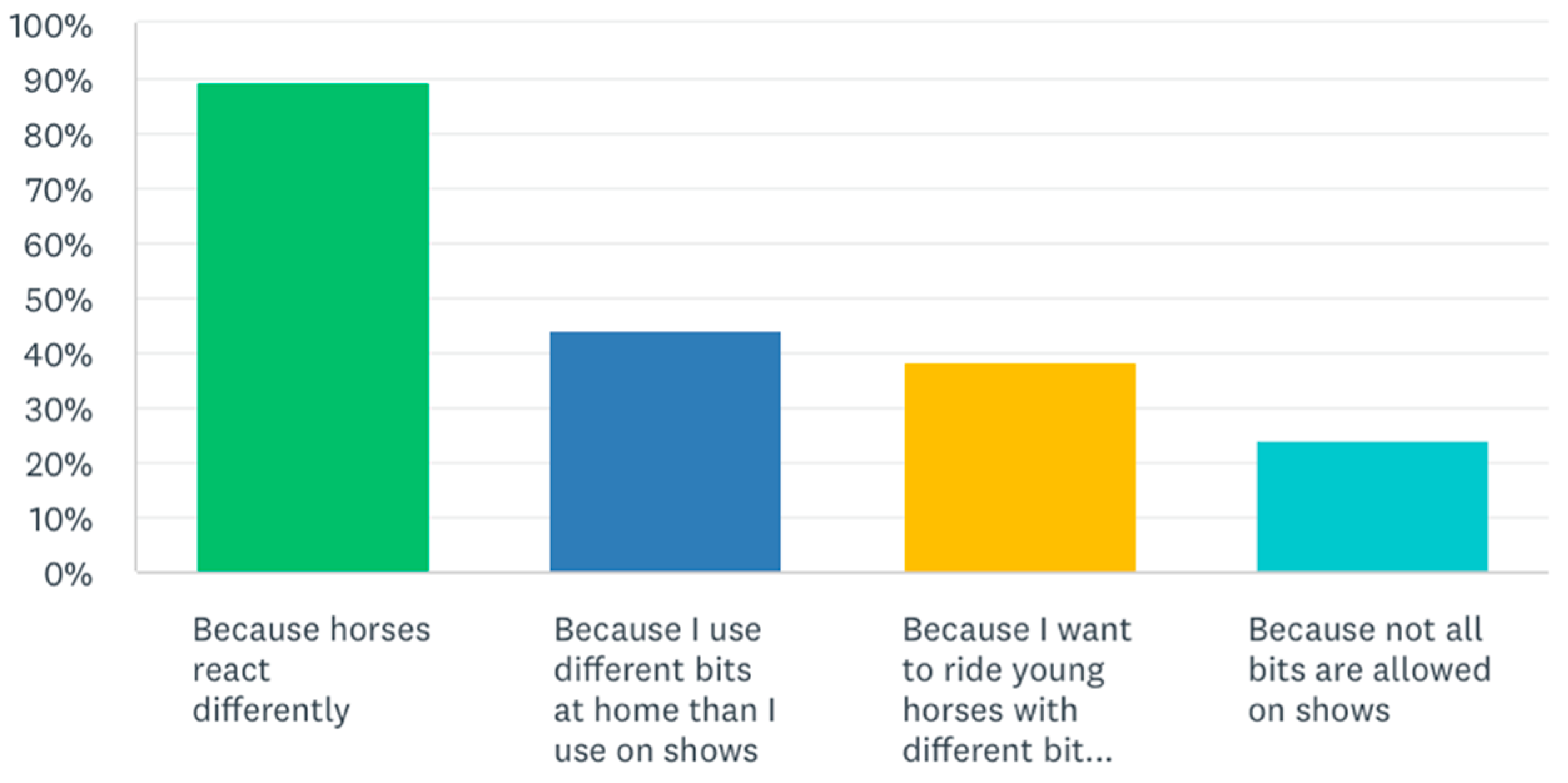

The primary reason cited for this was that different horses respond differently to different bits (89%, n=223). Additionally, 44% (n=110) of riders reported using different bits at home than they did during competitions. Also, 39% (n=98) of the riders said they were using different bits for young horses than for older ones. 25% (n=63) of the riders said that they could not use certain bits because they are not allowed on shows (

Figure 1).

The respondents gave various reasons when asked why they were using different bits at shows than at home. Some reasons included that certain bits are not allowed at shows, the horse is more energetic and excited at shows, that they have different expectations for control at shows, and that there are different requirements for show jumping than for base work at home. The main reason to use a different bit at shows than at home was that the bit at a show should have more impact, so that the riders have more control in unfamiliar or challenging situations, to manage horses that are more excited at shows compared to at home, and to better handle horses that react differently in the show environment. Other reasons included wanting to be able to quickly react to different situations, to not fake riding ability with a sharper bit at home, and to provide variety for the horse. Some riders reported using the same bit for both training and shows, while others used different bits to prevent the horse from becoming desensitized to a particular bit. When it comes to the material used 97% of the riders use metal bits, 65% use rubber and 18% also use leather bits.

In addition, riders were asked about the importance of certain factors when choosing a bit at home or at a show. The riders were asked 6 questions (

Table 1) and rate those answers from one to six (1 = not important to 6 = very important). The questions were asked twice, with the first round directed to the riders in their home-riding context, while the second round required them to answer as if they were on a show. When the participants were asked what they find important when choosing a bit at home, the horses’ satisfaction with the bit (mean = 5.59) and to have a consistent connection with the horses’ mouth (mean 5.22) was the most important. The factor of the horse chewing on the bit was also considered important, with a mean score of 4.27. Being able to turn the horse, having control and that the horse gives the rider pressure was less important for the riders at home (mean = 3.69, mean = 4.18, mean = 4.03, respectively). When asked what the riders find important when choosing a bit on a show, the answers shift a bit. The results showed that the most important factor for riders at shows was still the satisfaction of a horse with a bit with a mean of 5.33, which is significantly lower than when asked whether it is important for them at home. This is the same as with the importance of chewing on a bit (home = 4.27, show = 4.12). The second most important factor for riders was a consistent connection with the horse’s mouth with a mean rating of 5.19. There was no significant difference between the answers concerning riding at home or at a show. That the horse is easy to control at a show got a mean answer value of 4.97, which is significantly higher than when the same questions were asked for riding at home (

Table 1).

Video Analyses

The results of the study indicated a high level of agreement between the veterinary expert and the show jumper, with 95% consensus. The calculated Cohen's kappa coefficient demonstrated strong reliability and validity, with a value of 0.82. This indicates a high level of agreement between the two parties in assessing the behaviors.

However, when examining specific behaviors, it was observed that the two parties were least in agreement regarding the assessment of behaviors related to the movement of the ears. The Cohen's kappa coefficient for these behaviors was the lowest, measuring 0.61.

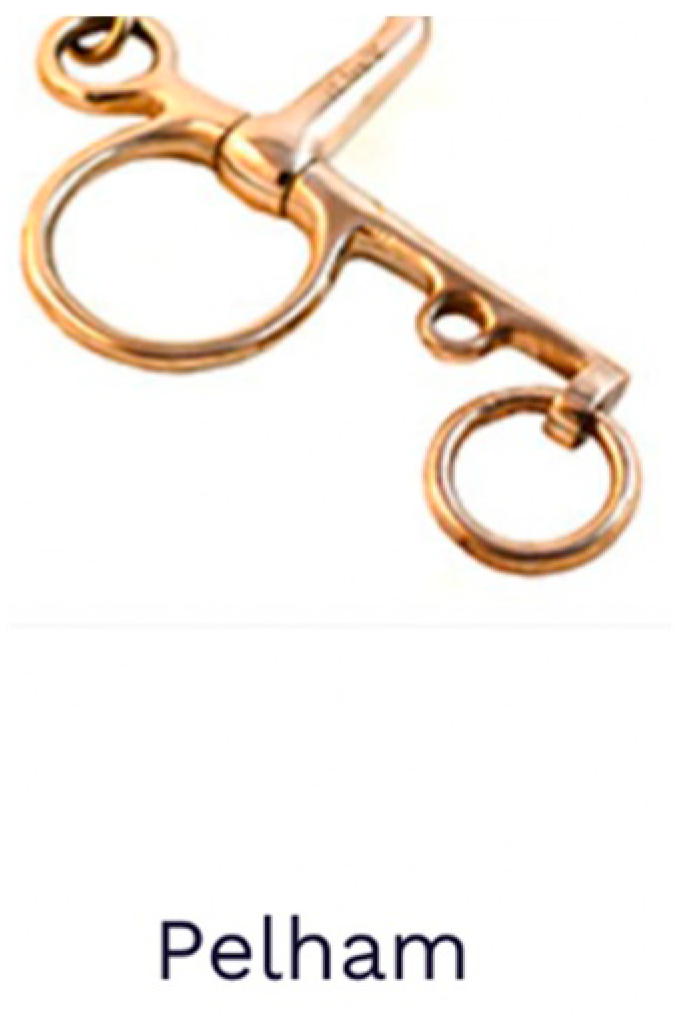

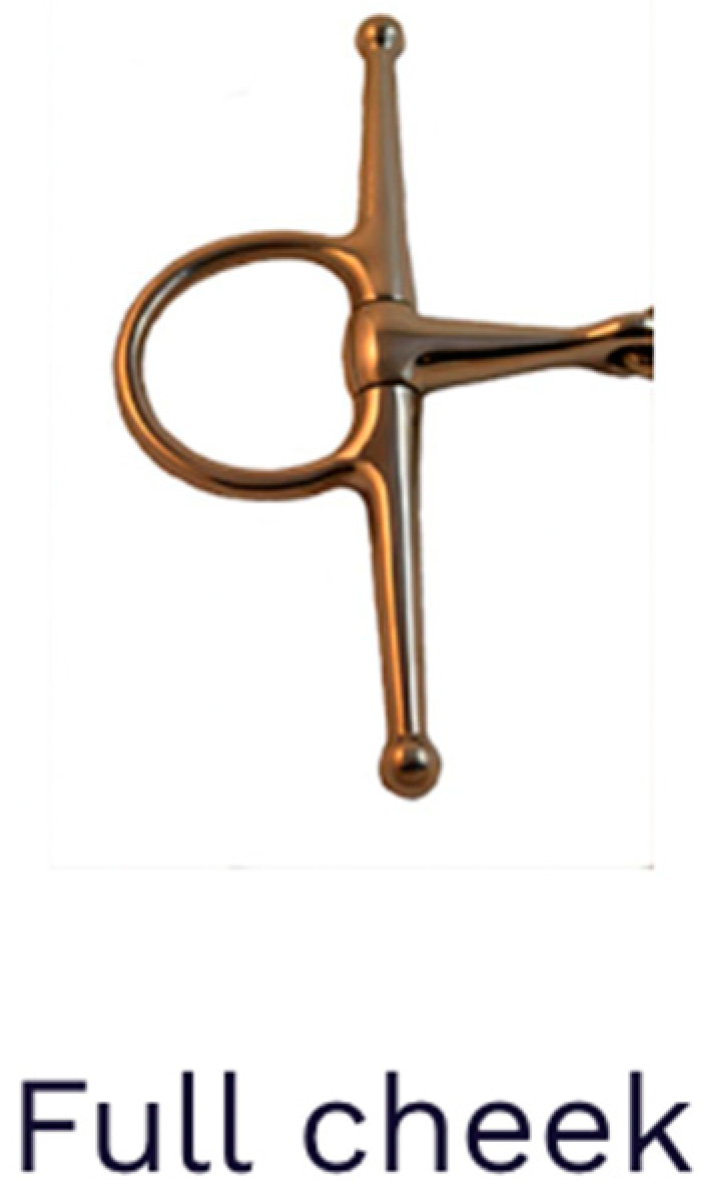

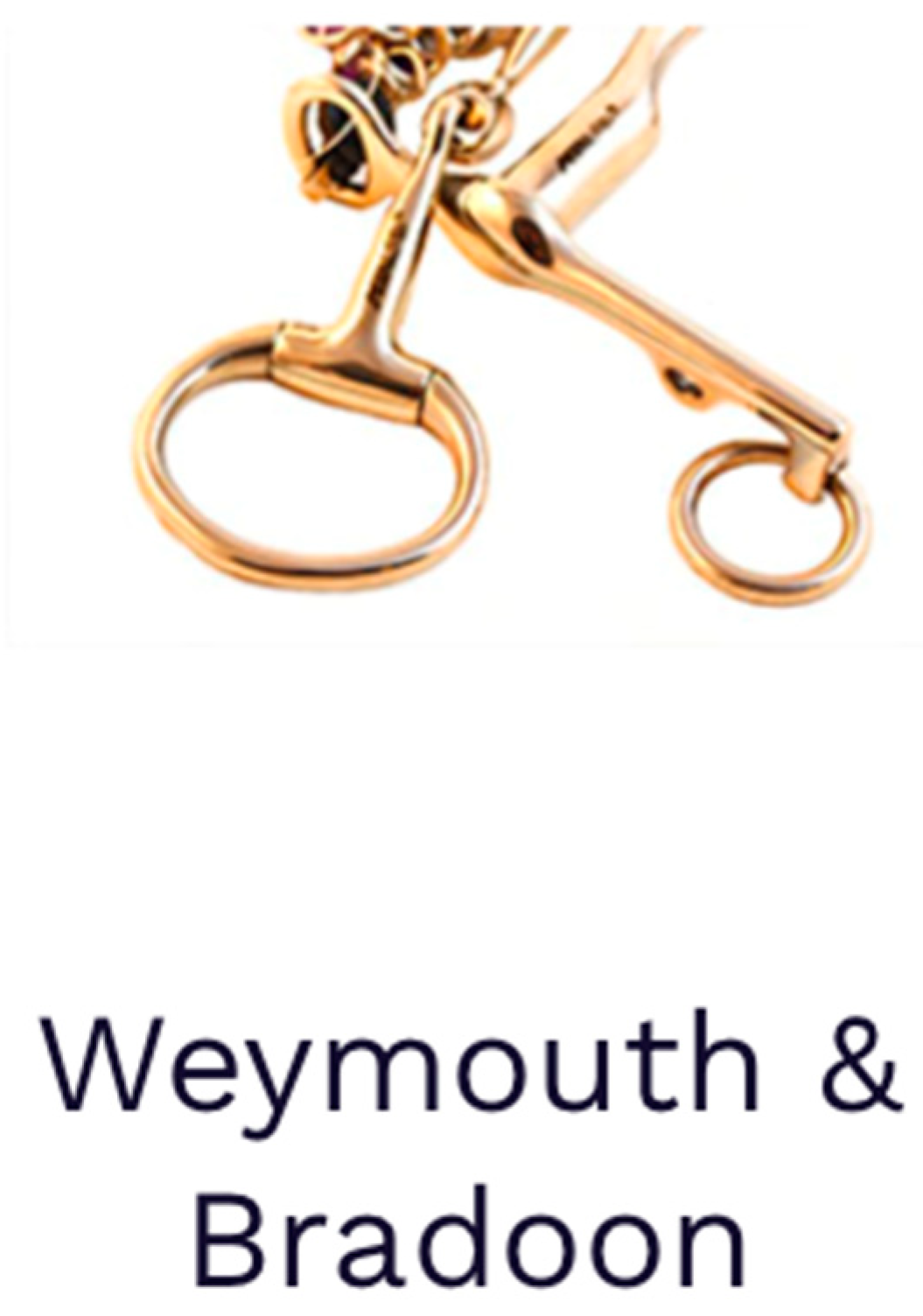

The analysis of the most commonly used bits revealed that the Pelham (Image 1) bit was utilized the most frequently, accounting for 25.4% of the total observations. The loose ring snaffle (Image 2) bit was also widely employed, representing 18.3% of the recorded instances. The full cheek elevator and Weymouth bits were used to a lesser extent, each accounting for approximately 8% of the observations. The curb gag bit was employed in 9.3% of the cases.

Image 2.

Loose ring snaffle.

Image 2.

Loose ring snaffle.

Prior to analyzing the specific bits, we assessed the overall frequency of defense movements exhibited by the horses.

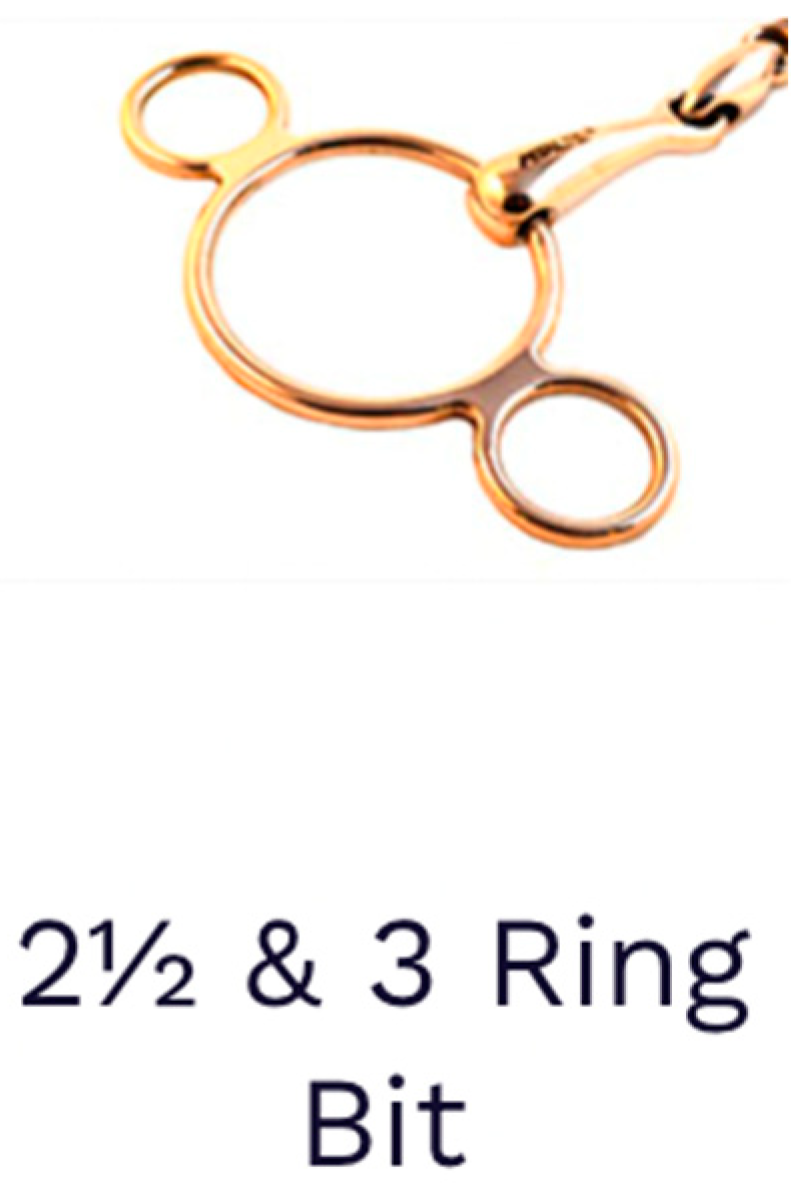

Upon examining the individual bits, it was found that the 3-ring bit (Image 3) and full cheek bit (Image 4) were the most commonly associated with defense movements, each accounting for more than 20% of the observations (21.8%, and 22.9% respectively).

Defense movements were seen in the range 10-20% for several bits (shown in

Table 2). Among the observed bits, the egg butt (Image 5), RNF bit (Butterfly flip bit) (Image 6), and hackamore (Image 7) demonstrated the least defense movements. However, it should be noted that there were only two observations with the RNF bit, limiting the validity of this finding.

Upon detailed analysis of the defense movements observed in the subjects, it becomes evident that the most frequently observed movement is the opening of the mouth, which occurred 254 times, accounting for 47.4% of the total instances. This defensive behavior was most observed with the 3-ring bit, occurring in 65% of the cases. Additionally, the opening of the mouth was observed in conjunction with the Curb gag (Image 8) and Weymouth bit (Image 9) in 60% of the instances, with the Kimblewick bit in 54.5% of the instances, and with the Pelham bit in 50% of the instances.

Image 9.

Weymouth & Bradoon

Image 9.

Weymouth & Bradoon

Notably, the opening of the mouth as a defensive movement was not observed when using the hackamore.

The second most common defense movement was “putting the ears back more than 10s” and it occurred in 32% of the cases and was most seen in mares. Also swishing the tail was mostly seen in mares (p>0.05). Head tilt of the horses to the side occurred in 24.8% and up and down head tilt occurred in 22.6% of the cases.

Discussion

The primary reason cited by riders for using different bits for different horses was that horses respond differently to different bits, as reported by 89% of respondents. This emphasizes the importance of selecting a bit that suits each horse's individual needs and preferences to optimize their comfort and performance. A significant majority of riders (92%) reported using different bits for different horses during competitions. This finding highlights the recognition among riders that horses have unique responses and requirements when it comes to bitting.

Additionally, 44% of riders reported using different bits at home compared to during competitions. This suggests that riders consider the specific demands and expectations of show environments when choosing a bit. The reasons provided by riders for this difference included certain bits not being allowed at shows, the horse being more energetic and excited at shows, different control expectations at shows, and varying requirements for different disciplines such as show jumping versus basic work at home.

When riders were asked about the factors they consider important when choosing a bit at home, two factors stood out: the horses' satisfaction with the bit and the desire for a consistent connection with the horse's mouth. These factors received mean ratings of 5.59 and 5.22, respectively, on a scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 6 (very important). These findings suggest that riders prioritize their horses' comfort and responsiveness when selecting a bit for use during regular training sessions or everyday riding.

Interestingly, the factor of the horse chewing on the bit was also considered important by the riders, with a mean score of 4.27. This indicates that riders recognize the significance of the horse's chewing behavior as an indicator of acceptance and comfort with the bit.

On the other hand, factors such as being able to turn the horse, having control, and the horse giving the rider pressure were deemed less important by the riders at home, with mean ratings of 3.69, 4.18, and 4.03, respectively. These results suggest that, in a home riding environment, riders may place less emphasis on strict control or specific performance outcomes and instead prioritize the overall satisfaction and connection with their horses.

When examining the riders' perspectives on choosing a bit at a show, some shifts in priorities become evident. The most important factor for riders at a show remained the horse's satisfaction with the bit, with a mean rating of 5.33. However, this score was significantly lower than the rating given for the same factor when choosing a bit at home (5.59).

Similarly, the importance of the horse chewing on the bit slightly decreased when riders were considering a bit for a show, with a mean score of 4.12. Although still significant, this decrease may be due to the different context of a show, where riders may focus more on performance and presentation rather than the horse's comfort alone.

The second most important factor for riders at a show remained a consistent connection with the horse's mouth, with a mean rating of 5.19. Interestingly, there was no significant difference between the importance of this factor at home and at a show. This indicates that riders consistently prioritize maintaining a reliable and responsive connection with their horses' mouths regardless of the riding environment.

Finally, the factor of the horse being easy to control at a show received a mean rating of 4.97, which was significantly higher than the rating given for riding at home. This suggests that riders place greater importance on having control over their horse's movements and behavior during show performances, potentially due to the competitive nature and higher expectations associated with shows. Also, it can be seen as dangerous to have less control in an unknown environment and with spectators around.

In summary, the results highlight that riders consider different factors when choosing a bit for their horses at home compared to when participating in shows. At home, riders prioritize their horses' satisfaction with the bit, consistent connection, and to some extent, the horse's chewing behavior. In contrast, at shows, riders still prioritize their horses' satisfaction and consistent connection but place more importance on control over the horse's movements. Understanding that riders choose different bits at a show than at home is crucial for accurately interpreting the consequences from using certain bits at shows. By recognizing and analyzing the reasons behind the variation at home and at shows, trainers, judges, and enthusiasts can gain valuable insights into the dynamics and welfare of the horse and the overall context of equestrian sports.

When looking at the video analyses there was a high level of agreement between the two observers, which indicates that the ethogram used in this study is a reliable and effective tool. The 95% consensus between the two parties demonstrates that they interpret and understand the behaviors in a similar manner. This high agreement rate suggests that the ethogram provides clear definitions and criteria for assessing the behaviors, ensuring consistency in their interpretation by different observers. It is to be mentioned that the Cohens kappa coefficient was the lowest for behaviors involving the movement of the ears. That suggest that there is some subjectivity and discrepancy in the interpretation of ear movements between the veterinarian and the show jumper. This is an important finding to be considered for future studies. In the observed shows, the Pelham bit emerged as the predominant choice, accounting for 25.4% of the total bit usage, closely followed by the loose ring bit at 18.3%. However, when surveying the riders, a noteworthy discrepancy arose. The majority of respondents (74%) indicated using the loose ring bit during jumping activities, while only 25% reported employing the Pelham bit. It is important to note that the survey did not explicitly specify whether the respondents were referring to show conditions alone or including training sessions as well. Therefore, we must consider the possibility that the observed bit usage at shows may not accurately represent the entirety of a horse's daily life.

The variation in reported bit usage suggests that riders may employ different bits during training sessions or in non-show settings. This highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding of bit preferences and usage patterns across various contexts. It is plausible that riders opt for different bits based on individual horse needs, training objectives, and personal preferences. Consequently, the bit choices observed at shows may not be fully representative of the overall bit usage experienced by the horses. We also see this in the open answer section, where riders stress the importance of a “lighter” bit at home, so the horse will be more sensitive to a “sharper” bit at shows. These findings underscore the importance of considering the broader context in which bit usage occurs and avoiding hasty generalizations based solely on show observations. To gain a more comprehensive understanding, future research should explore bit usage patterns in both training and show environments, while also considering individual horse-rider combinations. It is interesting to note that our survey revealed that the loose ring bit and egg butt are considered to be the lightest bits. These findings align with the regulations set by the Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung e.V. (2023), which allow these bits in the lower-level classes, typically attended by amateur riders. However, when we look at defense movements associated with these bits in higher-level classes, it becomes clear that they are not completely harmless.

On the other hand, the hackamore shows better results in terms of defense movements, with a lower occurrence. The hackamore combi, which combines elements of the hackamore and a bit, also performs well in this regard. It is important to note that the hackamore and the hackamore combi is not allowed in classes under 125cm in Germany.

We should think again about what we need from horse equipment and consider creating new designs that work in different ways on the horse's mouth and aim to better steer and control them.

By reevaluating our requirements, we can see if the current bit designs have any limitations and find new and better solutions that allow riders to communicate more effectively with their horses. This might involve working with experts in horse equipment design to create new designs that are more compatible with how horses naturally move and behave.

Introducing new designs that work differently on the horse's mouth or/and head can help us understand how different materials, construction, and pressure distribution affect the horse's reactions. By exploring these new possibilities, we can find gentler and more horse-friendly options that improve communication and overall well-being.

To make sure these new designs work well, we need to do thorough research and testing to see how they affect horse performance and happiness. By working together with equestrian professionals, researchers, and manufacturers, we can develop innovative designs that prioritize the horse's comfort, responsiveness, and partnership with the rider.

In conclusion, by reconsidering our needs and creating new designs that work differently on the horse's mouth and head, we can make improvements in horse equipment.

References

- Bracke, M.B.M., Spruijt, B.M., & Metz, J.H.M. (1999). Overall animal welfare reviewed. Part 3: Welfare assessment based on needs and supported by expert opinion. Available online: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/assawel.

- Cook, W.R. (1999). Pathophysiology of bit control in the horse. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 19(3), 196–204. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, I.J.H. (2005). Science-based assessment of animal welfare: Farm animals. OIE Revue Scientifique et Technique, 24(2), 483–492. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, S. (2022). The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram. Equine Veterinary Education, 34(7), 372–380. [CrossRef]

-

FEI. (2023). Available online: http://inside.fei.org.

- Luke, K.L., McAdie, T., Warren-Smith, A.K., & Smith, B.P. (2023). Bit use and its relevance for rider safety, rider satisfaction and horse welfare in equestrian sport. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 259, 105855. [CrossRef]

- Mench, J.A. (1998). Thirty years after Brambell: whither animal welfare science? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science : JAAWS, 1(2), 91–102. [CrossRef]

- Ohl, F., Arndt, S.S., & van der Staay, F.J. (2008). Pathological anxiety in animals. The Veterinary Journal, 175(1), 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Reiterliche Vereinigung eV, D. (n.d.). Mit Hinweisen zur WBO-Ausrüstung. Retrieved March 30, 2023. Available online: https://www.pferd-aktuell.de/bekanntmachungen.

- Uldahl, M. , & Clayton, H.M. (2019). Lesions associated with the use of bits, nosebands, spurs and whips in Danish competition horses. Equine Veterinary Journal 51(2), 154–162. [CrossRef]

-

View of Overall animal welfare assessment reviewed. Part 1: Is it possible? (n.d.). Retrieved June 14, 2023. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/ojs/index.php/njas/article/view/466/182.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).