1. Introduction

Agricultural modernization is currently the trend of more advanced agricultural development in the world(Cesco Stefano et al., 2023). Many modern digital information technology and agriculture are gradually integrated and developed. The development of digital intelligence enabled agriculture not only greatly improves agricultural production efficiency, but also promotes the development of economies of scale (Walter A et al., 2017; Disha and Mansaf, 2023). The development of tea industry is no exception. China is the birthplace of tea, with a history of over 5000 years in the development of the tea industry (Jing et al., 2021). Its tea production ranks first in the world and plays an important role in the tea industry. In the context of the development of digital intelligence enabled agriculture, Chinese tea's tea industry is gradually undergoing an intelligent transformation, combining the Internet, the Internet of Things, Big data, Cloud computing, Artificial intelligence and other technologies in various fields such as tea planting, production, processing, management and sales. Digital literacy will be an important foundation for intelligent agricultural development. Tea farmers operating on a moderate scale in China have the foundation and conditions for intelligent development of the tea industry (Hall and Leveen, 1978; Yu et al., 2019). Improving the digital literacy of these tea farmers will help them adapt to the intelligent process of tea industry development. This study selects land scale as the basic judgment indicator to determine the moderate scale management of tea gardens, that is, the tea plantation management area of tea farmers. The land scale range for moderate scale management of tea gardens is 1.3 to 3.4 hectares (Li and Hao, 2019; Fu and Fang, 2021).

For the research on digital literacy, both the definition of concepts and connotations, and the establishment of research frameworks have been relatively rich (Eshet Y, 2004). However, from the perspective of research objects, scholars have conducted more research on students, teachers, civil servants, and library staff (Martin et al., 2006; Alexander et al., 2016; Guzman et al., 2016; Havrilova and Topolnik, 2017; Ramírez et al., 2017; Napal et al., 2018). Compared to other research object groups, the research on digital literacy of farmers is relatively small and started relatively late (Littlejohn et al., 2012; Cetindamar Kozanoglu and Abedin, 2020; Hackfort, 2021; Danhua and Zhonggen, 2022; Shahrokh et al., 2022; Gutiérrez-ángel et al., 2022; Catherine and Bertrand, 2022; Campanozzi et al., 2023; Reddy et al., 2023). Moreover, research on the digital literacy of tea farmers is currently scarce. From the perspective of research methods, most studies focus on evaluation and adopt qualitative research methods, with less empirical analysis methods used for research on digital literacy. From a research perspective, most current research on smart agriculture has put forward requirements for farmers' digital literacy, but research on improving their digital literacy is still rare. Overall, the definition of digital literacy in the field of tea farmers' behavior is still relatively vague. Therefore, based on existing research, this study defines tea farmers' digital literacy as their own digital knowledge and skills in the context of digital intelligence empowering agricultural development (Gilster P, 1997; Bawden D, 2001; Dungang et al., 2022).

In summary, although existing literature has conducted research on digital literacy on many subjects, research is rarely based on mature and systematic theoretical frameworks. The overall theoretical framework and explanatory power of the research are weak, and the persuasiveness of the influencing factors revealed in the research needs to be further improved. At present, the UTAUT theoretical model is widely used in the field of digital information technology to conduct research on acceptance willingness and behavior (Molina et al., 2013; Michels and Musshoff, 2020). Although some of the research objects are farmers, most of the research focuses on major food crops or animal husbandry, and little attention is paid to tea farmers or tea as a Cash crop (He and Zeng, 2018; Nejadrezaei et al., 2018; Rusere et al., 2019; Amir et al., 2020; He and Zeng, 2020; Ronaghi and Forouharfar, 2020; Sabbagh and Gutierrez, 2022). Therefore, this study expands the UTAUT original model by introducing Personal innovativeness theory and Self-efficacy theory, improves the theoretical framework of the study, and studies the influencing factors of moderate scale tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior. On the one hand, this study enriches the literature of tea farmers in the field of digital literacy and proposes some targeted strategies, and on the other hand, by integrating personal innovativeness theory and self-efficacy theory, this study improves the universality of the UTAUT theoretical model and provides theoretical reference for other similar research issues.

2. Theoretical foundation

2.1. UTAUT theory

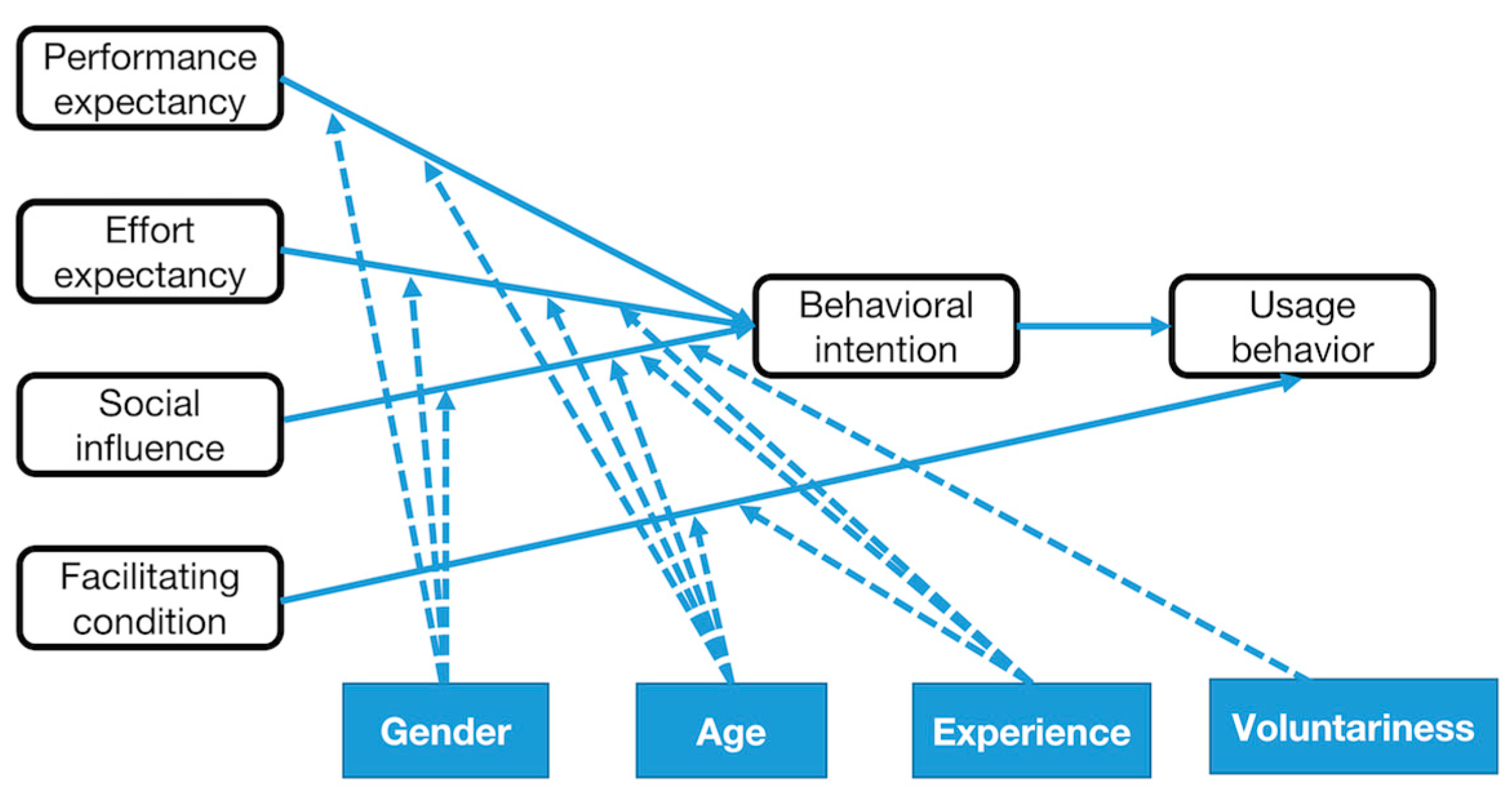

The UTAUT theory was put forward by Venkatesh and other scholars in 2003 on the basis of integrating eight theories, namely, "Technology acceptance model, Theory of reasoned action, Theory of planned behavior, Motivation model, Composite model, PC utilization model, Social cognitive theory and Diffusion of innovations" (Venkatesh V et al., 2003). This theory made up for the defects of the eight theoretical research elements, low prediction and interpretation, and single research perspective, and built the UTAUT theoretical model. Its explanatory power is as high as 70% (Li and Yuan, 2020; Chen and Liang, 2021). The UTAUT theoretical model includes four core independent variables, namely performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating condition. Performance expectancy refer to the degree to which individuals subjectively believe that using information technology will provide assistance and benefits for their work. Effort expectancy refers to the level of effort and perceived difficulty that individuals need to put into the process of adopting and accepting information technology. Social influence refers to the degree to which individuals are influenced by the opinions of others from the outside world when adopting or accepting new information technology, especially the influence of close groups, familiar people, and industry experts around them. Facilitating condition refers to the level of support provided by an individual's organizational or technological infrastructure in the process of using information technology. In this model, the behavioral willingness of the study subjects is influenced by three variables: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence. Facilitating condition and willingness directly affect individual behavior. At the same time, the model has four moderating variables, namely gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of the study subjects.

Venkatesh applied the UTAUT theoretical model to organizations with strong heterogeneity, proving that the explanatory power of the model reached 70%. It has been widely applied by many scholars in fields such as behavior, psychology, and digital information technology, and has become an effective tool for studying the willingness and behavior of digital information technology acceptance. It is a relatively authoritative and typical model (Beza et al., 2018; Narine et al., 2019; Ronaghi and Forouharfar, 2020; Von Veltheim and Heise, 2021). During the application and research process of the UTAUT theoretical model, it is allowed to increase or decrease the variables in the model according to the characteristics and research needs of different research objects, or integrate other research theories to further improve the explanatory power of the model. At present, the UTAUT theoretical model is widely used, and scholars have used the UTAUT theoretical model as the basis for the construction of research models in related studies such as the willingness and acceptance behavior of farmers' digital information technology systems, and the acceptance behavior of new agricultural technologies.

In this study, tea farmers' digital literacy mainly refers to their own digital knowledge and skills. The improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy will be manifested in the learning and acceptance of digital knowledge and skills, and the strengthening of their own digital knowledge and skills, which is farmers' acceptance of digital information technology. Therefore, this study will be based on the UTAUT theoretical model to construct a model of influencing factors on the digital literacy improvement behavior of moderate scale tea farmers (

Figure 1).

2.2. Personal innovativeness theory

The theory of personal innovativeness was proposed by Midgley and Dowling (1978) in 1978, which defines personal innovativeness as the degree of acceptance of new ideas or things by individuals, reflecting their enthusiasm for accepting new things. It is the starting point and driving force for individual innovation activities. Rogers (1979) defined personal innovativeness as the tendency of individuals to try new things or accept new technologies in Diffusion of innovations. The stronger the individual's innovation, the more willing they will be to try and accept new things or technologies, and explore the beneficial aspects of new things or technologies for themselves. Scholars such as Agarwal (1998) have found in their empirical research on willingness and behavior to accept information technology that personal innovativeness has a direct or indirect impact on the willingness and behavior to adopt new information technology. The stronger an individual's innovation, the stronger their willingness or behavior to accept new information technology. Personal innovativeness is an inherent characteristic of individuals, and individuals with different levels of innovation often have different cognitive and processing methods towards new things. For individuals with stronger innovation, they are willing to actively try new things, accept new knowledge or technology, and then engage in innovative practices, while individuals with lower innovation are the opposite. Currently, many scholars have found that personal innovativeness has a certain impact on users' willingness and acceptance behavior of information technology adoption, and personal innovativeness will be considered in research.

2.3. Self-efficacy theory

The theory of self-efficacy was proposed by American psychologist Bandura (1977) in 1977. It believes that self-efficacy is an individual's subjective judgment of their ability to complete a task and achieve expected goals in a certain context. It can also be understood as an individual's level of confidence in organizing and executing a series of actions to produce certain results, which to some extent affects the success of a task. For different research fields or research objects, self-efficacy will show differences and have a certain degree of specificity. In specific studies, self-efficacy can better predict individual willingness and behavior. Studies have shown that self-efficacy can have varying degrees of impact on an individual's cognition, emotions, motivation, and behavior, sometimes mediated by cognition, emotions, and motivation (Bandura Albert and Cervone Daniel, 1986). Self-efficacy is a complex process of self persuasion. The stronger a person's self-efficacy, the not only can they have a positive view of things, but they can also develop a self reinforcement within themselves and externalize it into actual human behavior. Therefore, they voluntarily adhere to and practice, and the greater the possibility of achieving success, while a weaker individual's self-efficacy is the opposite. The UTAUT theory is formed on the basis of eight major theories, including Bandura's social cognition theory, and self-efficacy theory is one of the constituent theories of social cognition theory. Venkatesh did not consider self-efficacy variables when constructing the UTAUT theory model, but self-efficacy can have a certain impact on individual behavior and willingness, and will show differences according to different studies.

Therefore, this study extends the UTAUT original model by integrating Personal innovativeness theory and Self-efficacy theory, taking into account the two influencing factors of personal innovativeness and self-efficacy, and exploring the extent to which personal innovativeness and self-efficacy of tea farmers affect their willingness and behavior to improve digital literacy.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. Performance expectancy and willingness to improve digital literacy

In this study, performance expectancy refer to the degree to which tea farmers subjectively believe that the digital knowledge and skills they possess after improving their digital literacy can provide assistance and benefits for the intelligent development of their tea planting, production, and daily management of tea gardens. Venkatesh's research indicates that the performance brought about by the information technology or information system that individuals receive positively affects their willingness to accept (Venkatesh V et al., 2003). In the field of digital information technology acceptance willingness and behavior, the performance expectancy in the UTAUT theoretical model are considered the most powerful predictive tool. If tea farmers improve their digital literacy and can more easily access relevant information about tea, they can apply relevant digital equipment and platforms in tea cultivation, production, processing, and sales, improve work efficiency and create profits. They will be willing to improve their digital literacy (Zscheischler et al., 2022). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Performance expectancy have a significant positive impact on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy.

3.2. Social influence and willingness to enhance digital literacy

Social influence refers to the degree to which tea farmers are influenced by the opinions of others around them, such as family and friends, industry experts, and government calls, when they adopt digital knowledge and skills to improve their digital literacy. Venkatesh (2003) believes that an individual's willingness and behavior are influenced by important stakeholders, and when social influence is positive, it can positively enhance the individual's willingness and behavior. Lima (2018) found that farmers are more willing to adopt new agricultural related technologies promoted by the government. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Social influence has a significant positive impact on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy.

3.3. Effort expectancy and willingness to improve digital literacy

Effort expectancy refers to the level of effort and perceived difficulty that tea farmers need to put into learning digital knowledge and mastering digital skills in the process of improving their digital literacy. Venkatesh (2003) believes that individuals will weigh the effort and difficulty required before learning and using new technologies, and the expectancy of effort will have a positive impact on their willingness to use new technologies. Davis (1989) believes that individual acceptance and use of any information technology require time and effort in order to understand, master, and apply it. If the cost of time and effort spent on learning and using information technology is too high, then individuals will reduce their willingness to accept it. If tea farmers are willing to invest time and effort in improving their digital literacy and believe that the difficulty level is not high, then tea farmers will be willing to improve their digital literacy. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Effort expectancy has a significant positive impact on the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy.

3.4. Personal innovativeness and willingness to enhance digital literacy

Personal innovativeness refers to the acceptance and enhancement of digital knowledge and skills by tea farmers through innovative attempts to develop the tea industry through smart agricultural technology, leading to the improvement of their digital literacy. Van Raaij and Tom have shown that individuals with stronger innovation are more inclined to embrace and use new technologies (Van Raaij and Schepers, 2008; Tom et al., 2013). Rogers (1979) believes that individuals with a high level of innovation awareness are more willing to accept and use new technologies, and are able to bear the risks or uncertainties associated with the use of new technologies. Obienu and Amadin's (2020) research has shown that if individuals possess high levels of personal innovativeness, they are more likely to master new technologies and apply them more quickly. In the context of digital intelligence empowerment, modern digital information technology and agriculture are gradually being deeply integrated and developed. Farmers developing smart agriculture need to have digital knowledge and skills that match it. Tea farmers have a stronger willingness to innovate and apply digital technology in activities such as tea planting, production, and tea garden management, and will be more willing to improve their digital literacy. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Personal innovativeness has a significant positive impact on the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy.

3.5. Self-efficacy and willingness to improve digital literacy

Self-efficacy refers to the subjective judgment of tea farmers on whether they can improve their digital knowledge and skills and achieve their inner expectancy when improving their digital literacy in the context of the digital age, that is, the level of confidence in improving their digital literacy and achieving certain results. Bandura and Cervone (1986) believes that self-efficacy emphasizes an individual's subjective judgment and is their subjective expectancy of being competent for a certain job. Tsai H S and Kundu believe that an individual's self-efficacy towards new technologies is reflected in their belief in learning knowledge and mastering new skills related to new technologies, and their self-efficacy will have an impact on their behavioral intentions (Tsai H S and Larose, 2015; Kundu et al., 2021). If tea farmers have a high sense of self-efficacy, they will have a positive view of improving their digital literacy, and will be more proactive in adhering to the improvement of their digital literacy. They will confidently overcome the difficulties in the improvement process and be confident that they can achieve their goals. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Self-efficacy has a significant positive impact on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy.

3.6. Facilitating condition and digital literacy improvement behavior

Facilitating condition refer to the degree to which tea farmers can obtain support from relevant organizations or external resources during the process of improving their digital literacy. They can be specifically defined as resources that can be allocated to enhance their digital literacy and acquire relevant digital knowledge and skills, such as economic conditions, land conditions, convenient ways to obtain new agricultural technologies, methods to solve difficulties, and policies and subsidies provided by the government. Venkatesh (2003) believes that if individuals are able to receive new technologies or things with favorable external conditions, they will be more willing to learn and accept them. If tea farmers can receive help from the government or other organizations, as well as support from external resources, in the process of improving their digital literacy, it will help them improve their digital knowledge and skills. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Facilitating condition have a significant positive impact on tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior.

3.7. Willingness and behavior to enhance digital literacy

The willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy refers to the degree to which they are willing to try to improve their digital knowledge and skills. The behavior of improving digital literacy mainly refers to the recent improvement of digital knowledge and skills by tea farmers, as well as the subsequent strengthening of their own digital literacy. Angel, Ahikiriza and other scholars have confirmed that behavioral intention has a significant positive effect on behavior (Angel and Ignacio, 2010; Ahikiriza et al., 2022). Zhang weiwei, Turner and other scholars believe that behavioral intention can predict actual behavior (Zhang Weiwei, 2020; Turner et al., 2021). Most theoretical models on technology adoption and acceptance include two variables: willingness and behavior, which can predict and judge behavior. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7: The willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy has a significant positive impact on their digital literacy improvement behavior.

3.8. The mediating role of willingness to enhance digital literacy

In the original model of UTAUT theory, performance expectancy, social influence, and effort expectancy have a positive impact on willingness, and then affect behavior. From the causal logic of UTAUT theory model, there is an inherent connection between performance expectancy, social influence, and effort expectancy and willingness and behavior. Moreover, the UTAUT theory model has different degrees of influence on willingness and behavior by the influencing factors of the model under different backgrounds and research object conditions. Models have varying degrees of explanatory power for behavior prediction (Anil Gupta et al., 2020). Therefore, this study assumes that the willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy has a mediating effect on performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, personal innovativeness, and self-efficacy in promoting their digital literacy. Based on this, the following hypothesizes are proposed:

H8: The willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy plays a mediating role between performance expectancy and tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior;

H9: The willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy plays a mediating role between social influence and tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior;

H10: The willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy plays a mediating role between effort expectancy and tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior;

H11: The willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy plays a mediating role between personal innovativeness and tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior;

H12: The willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy plays a mediating role between self-efficacy and tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior.

3.9. The moderating effect of gender, age, and experience

According to the characteristics of tea farmers and research needs, adjust the regulatory variables in the original model of UTAUT theory and delete the "voluntariness" regulatory variables. Because the willingness and behavior of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy in this study are initiated independently, tea farmers can choose whether to improve their digital literacy according to their own preferences (Xie Kexiao et al., 2022). Therefore, the "voluntariness" moderating variable cannot be used as a reference in this study model. Firstly this study does not retain the moderating variable of "voluntariness". Secondly, the regulating variable "experience" in the original model of UTAUT theory is concretized as "time spent on tea cultivation". Based on this, the following hypothesizes are proposed:

H13: Gender plays a moderating role in the impact of performance expectancy on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H14: Gender plays a moderating role in the social influence on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H15: Gender plays a moderating role in the impact of effort expectancy on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H16: Age plays a moderating role in the impact of performance expectancy on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H17: Age plays a moderating role in the social influence on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H18: Age plays a moderating role in the impact of effort expectancy on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H19: Age plays a moderating role in the influence of facilitating condition on tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior;

H20: Experience plays a moderating role in the social influence on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy;

H21: Experience has a moderating effect on the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy through effort expectancy;

H22: Experience has a moderating effect on the improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy behavior through facilitating condition.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Research model

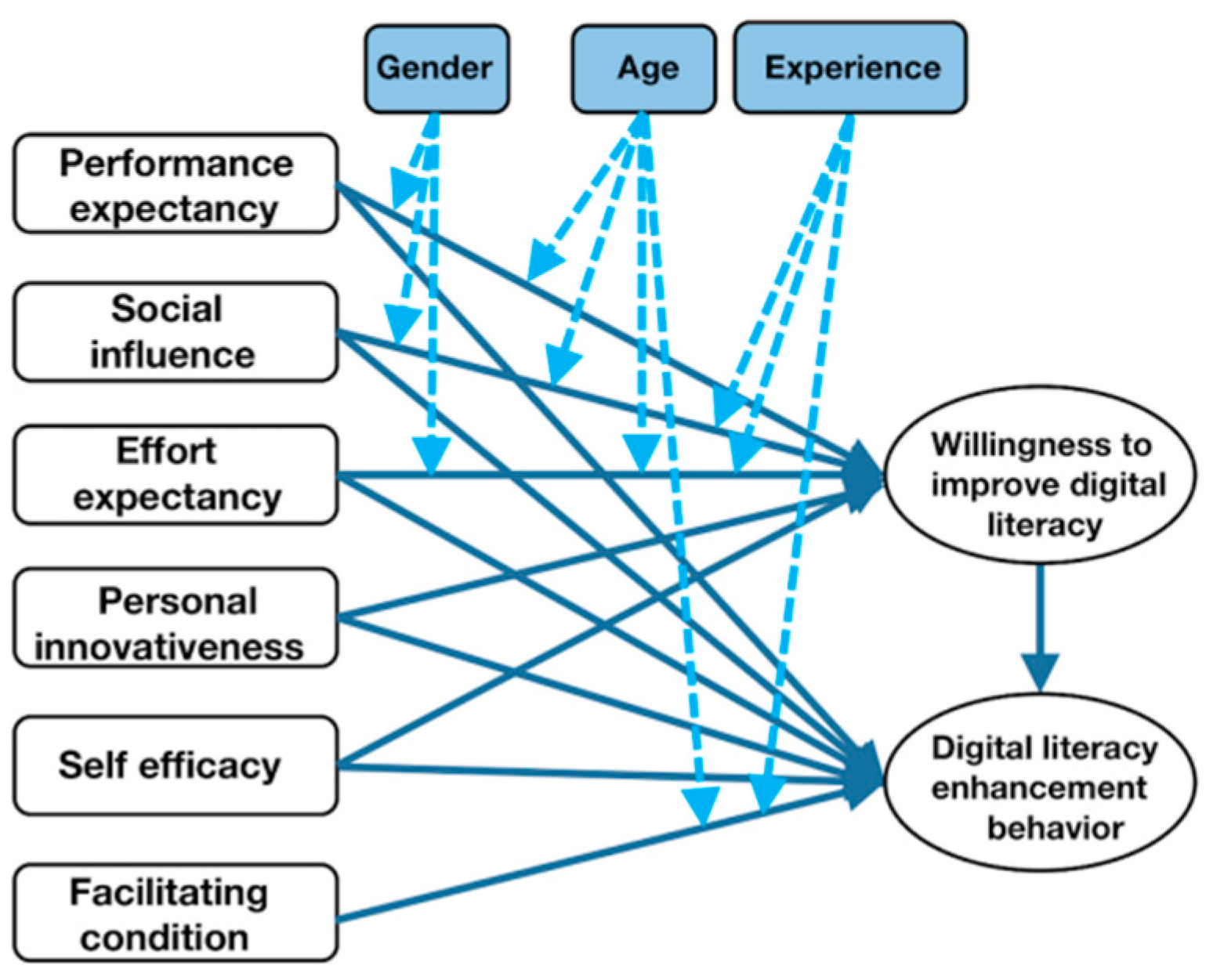

Based on the above theoretical foundations and research hypotheses, this article extends the UTAUT theoretical model and innovatively establishes a new research model to explore the digital literacy improvement behavior of tea farmers in moderate scale operation. The model includes independent variables, intermediary variables, moderating variables, and dependent variables(

Figure 2).

4.2. Questionnaire design

The production of this research questionnaire is based on the existing relevant literature, modified and improved under the guidance of professors from the Department of Tea Science and the Department of Business Economics of Anxi Tea College, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Midgley and Dowling, 1978; Rogers, 1979; Bandura, 1977; Davis, 1989; Venkatesh V et al., 2003; Lima, 2018; Anil Gupta et al., 2020; Ahikiriza et al., 2022; Xie Kexiao et al., 2022). After the completion of the initial questionnaire, a pre survey of tea farmers was conducted, and appropriate adjustments were made according to the feedback, ultimately forming a scientific and reasonable questionnaire. The survey questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part is a questionnaire explanation, which mainly explains the purpose of the questionnaire and explains related concepts, so that the respondents can understand the background of filling out the questionnaire and effectively answer the questionnaire content. The second part is about the basic situation investigation of tea farmers. The third part is the related items of eight variables in the constructed model. These eight variables are respectively tea farmers' performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, personal innovativeness, self-efficacy, facilitating condition, digital literacy promotion willingness and digital literacy promotion behavior. Each variable is represented by four to six items. The Likert five point scale scoring method is used for scoring measurement, with 5 points for strongly agreeing, 4 points for strongly agreeing, generally 3 points, 2 points for strongly disagreeing, and 1 point for strongly disagreeing.

4.3. Data collection and analysis method

The survey time of tea farmers is from September 2022 to November 2022. The survey was carried out in 11 places including Gande Town, Xiping Town, Lutian Town, Huqiu Town, Jiandou Town, Penglai Town, Changkeng Township, Longjuan Township, Xianghua Township, Lantian Township and Daping Township in the contiguous tea area of Anxi County. The data and information required for this study were collected through offline questionnaire surveys and interviews among tea farmers with a relatively contiguous planting area of 1.3 to 3.4 hectares. A total of 464 questionnaires were collected, with a total of 440 valid questionnaires and an effective recovery rate of about 95%.

In this study, SPSS and AMOS software were used to sort out and analyze the collected data. The analysis content mainly includes: descriptive statistical analysis of sample basic characteristics, reliability and validity test of sample data, structural equation model verification, and mesomeric effect and moderation test.

4.4. Demographic profile

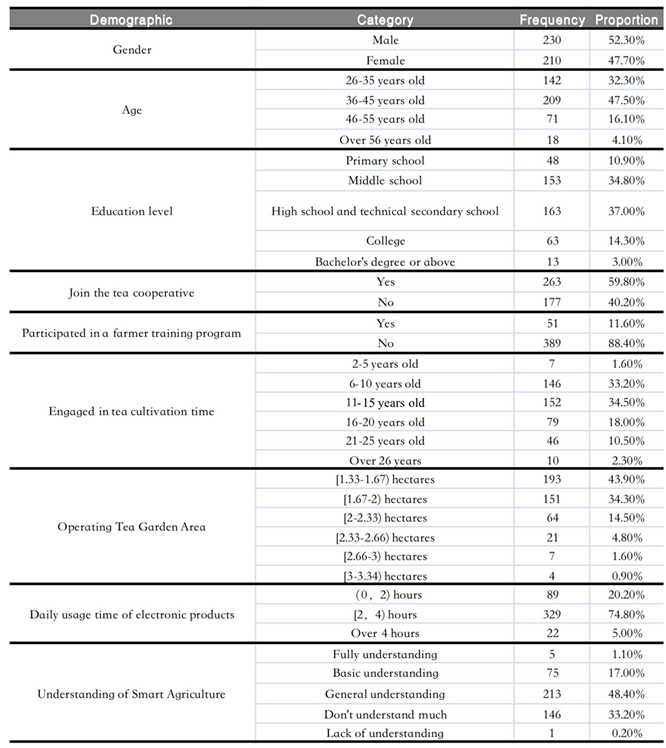

From the

Table 1, it can be seen that in terms of gender, there is not much difference between the proportion of males and females. In terms of age, the proportion of people aged 26 to 45 is relatively large. In terms of educational level, the majority of tea farmers mainly have junior high school, high school, and technical secondary school degrees, with a relatively small proportion of people at or above university level. Moreover, most tea farmers have not participated in farmer training. The proportion of tea farmers engaged in tea cultivation for 6-15 years is as high as 67.7%. In terms of understanding of smart agriculture, the proportion of people who fully understand it is 1.1%, while the proportion of people who basically understand it is 17%. It can be seen that there are not many people who know about smart agriculture.With a general understanding of 48.4% and a lack of understanding of 33.2%, it indicates that most tea farmers are in a state of partial understanding of smart agriculture.

5. Results of statistical analysis

5.1. Measurement model analysis

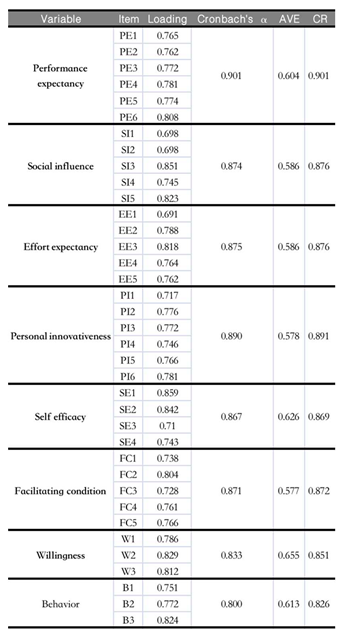

This study applied SPSS software to analyze the reliability and effectiveness of the 8 measurement dimensions in the questionnaire (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). As can be seen from the

Table 2, Cronbach's α for 8 measurement dimensions. The Cronbach's α coefficients are all greater than 0.8. The coefficient test results all meet the qualified standards, indicating that the measurement model has high reliability and good reliability. The factor load of each item corresponding to the 8 variables is above 0.6, meeting the standard requirement of a factor load greater than 0.5, indicating that the items in the scale have good representativeness for the variables to be measured. The extracted difference of two squares AVE value of the eight variables is greater than 0.5, and the combined reliability CR value is greater than 0.8, and the CR value meets the standard requirement of greater than 0.7, which indicates that the measurement model has good internal consistency and aggregation validity (Bontis et al., 2002; Ros and Field, 2006; Hair et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2016).

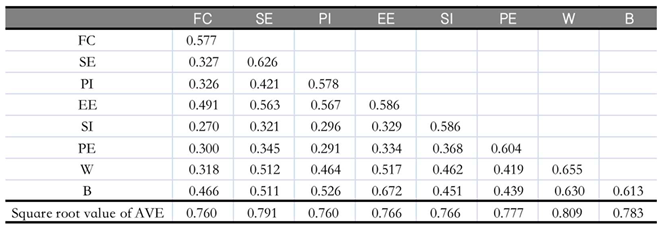

From the

Table 3, it can be seen that the root of each AVE of the 8 variables is greater than the correlation coefficient of each paired variable, indicating that there is good discrimination between the variables in the measurement model (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

5.2. Structural equation model analysis

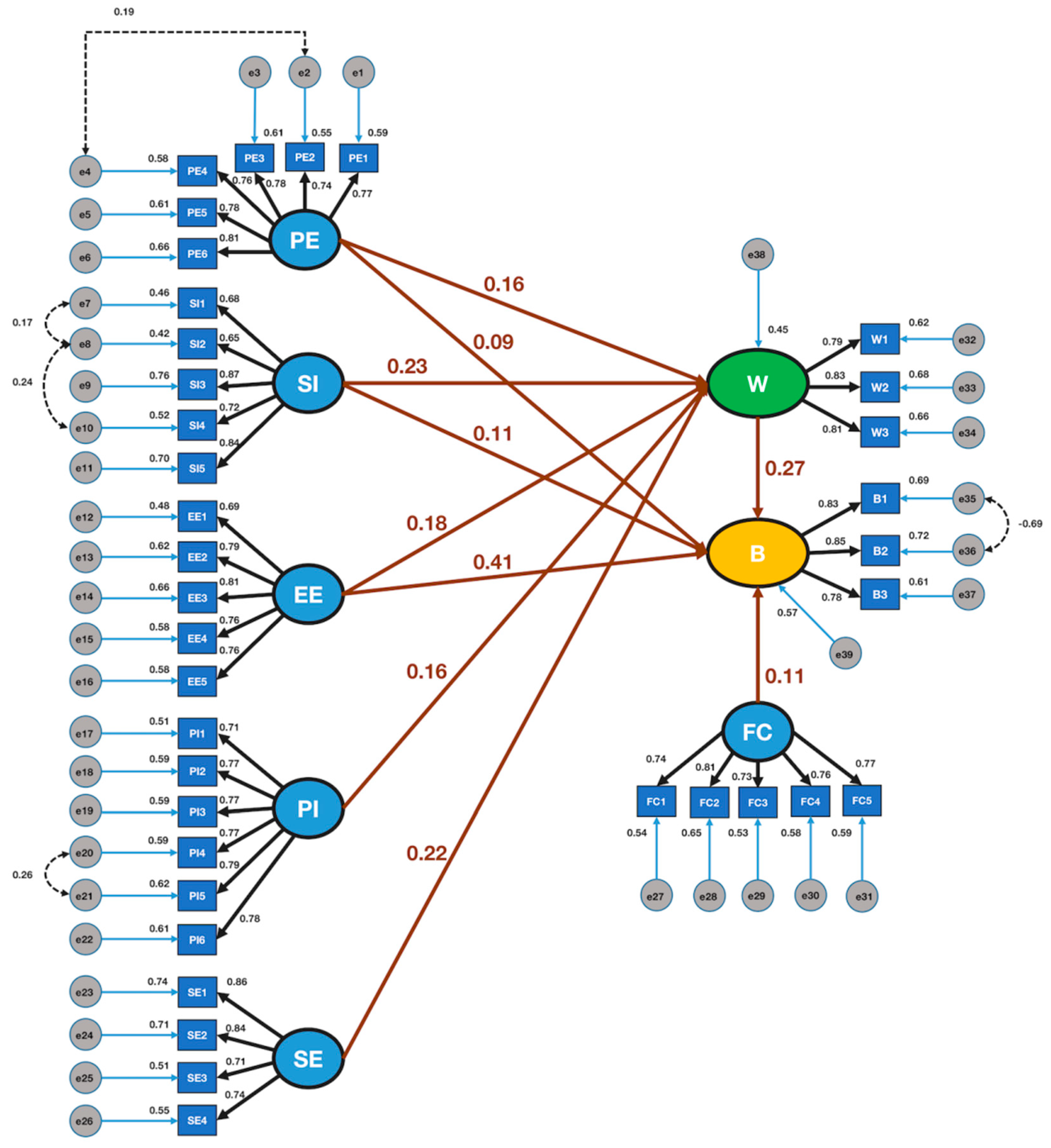

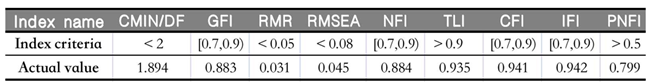

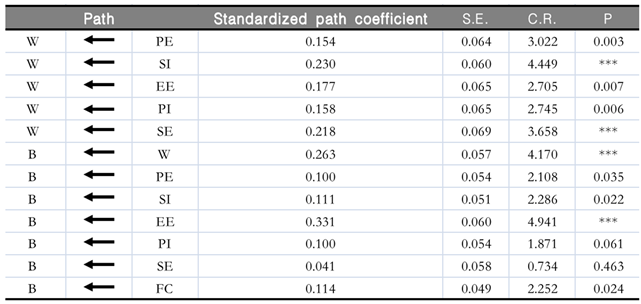

From

Table 4, it can be seen that the various indicators of the initial model of influencing factors on the digital literacy improvement behavior of moderate scale tea farmers are basically on the ideal fit index coefficient standard, with CMIN/DF of 1.894, GFI value of 0.883, RMR value of 0.031, RMSEA value of 0.045, NFI value of 0.884, TLI value of 0.935, CFI value of 0.941, IFI value of 0.942, and PNFI value of 0.799. Therefore, the adaptability of the model in this study is relatively good and theoretically acceptable (Bollen Kenneth A, et al., 2022).

The

Table 5 shows the results of the initial model path analysis report. Performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, personal innovativeness, and self-efficacy all have a significant positive impact on the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy (p<0.05). Assuming that H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 are valid. Facilitating condition and tea farmers' willingness to improve digital literacy have a significant positive impact on their digital literacy improvement behavior (p<0.05), assuming that H6 and H7 are valid. Performance expectancy, social influence, and effort expectancy all have a significant positive impact on tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior (p<0.05), while personal innovativeness and self-efficacy do not have a significant positive impact on tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior (p>0.05). This indicates that tea farmers' willingness to improve digital literacy can play a mediating role, playing a partial mediating role between performance expectancy,social influence, and effort expectancy on digital literacy improvement behavior, and playing a complete mediating role between personal innovativeness and self-efficacy in enhancing digital literacy behavior. Assuming H8, H9, H10, H11, and H12 are valid.

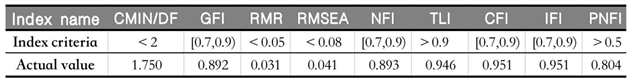

Based on the fitting coefficients of the initial model and the path analysis report, the initial model is modified to remove insignificant paths. At the same time, the residual terms with strong correlation are connected according to the corrected index MI value to obtain a more ideal structural model. From the

Table 6, it can be seen that compared with the overall adaptation results of the initial model, all indicators of the modified model's fitting coefficient have improved and basically meet the standard. The fitting degree of the model in this study is good.

From the

Table 7, it can be seen that the revised path analysis results have reached a significant level.

Figure 3 shows the revised structural equation model and path coefficients.

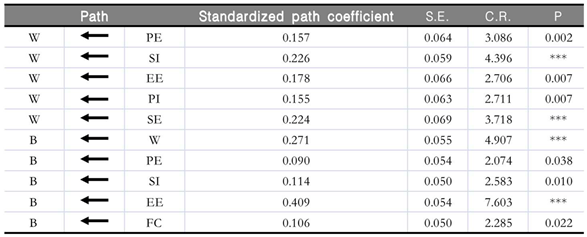

5.3. Test of Mesomeric effect of variables

From the path analysis results, we can see that performance expectancy, social influence and effort expectancy have a direct effect on tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy and their behavior to improve their digital literacy. Therefore, we will test the Mesomeric effect of tea farmers' willingness to improve their digital literacy and explore the proportion of Mesomeric effect. This study uses the Bootstrap method to test the Mesomeric effect. With reference to the Bootstrap Mesomeric effect test procedure, considering the 440 sample data of this study, the sampling times are set to 5000, and the bias correction confidence interval is set to 95%. If the upper and lower limits of the 95% bias correction confidence interval do not contain 0, then the Mesomeric effect is significant.

From the

Table 8, it can be seen that the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy plays a partial mediating role in the impact between performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, and digital literacy improvement behavior. According to the proportion of indirect effects, the order is effort expectancy (27%), performance expectancy (47%), and social influence (49%).

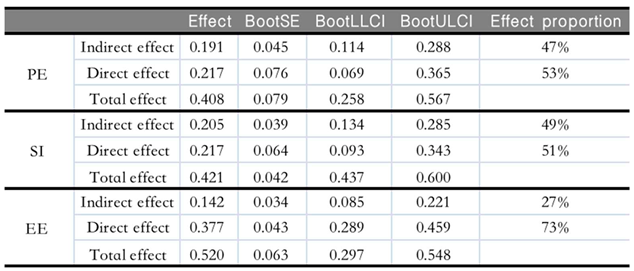

5.4. Verification of the moderating effect of variables

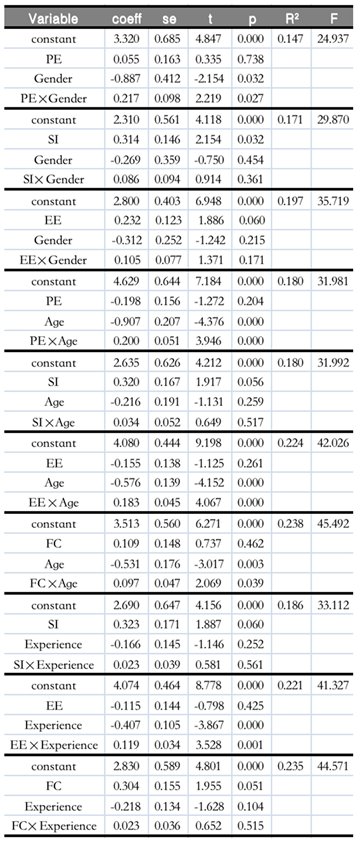

This study used Model 1 in the SPSS plugin Process to test the moderating effects of the three moderating variables of tea farmers' gender, age, and experience in the model (Hayes, 2018).

From the

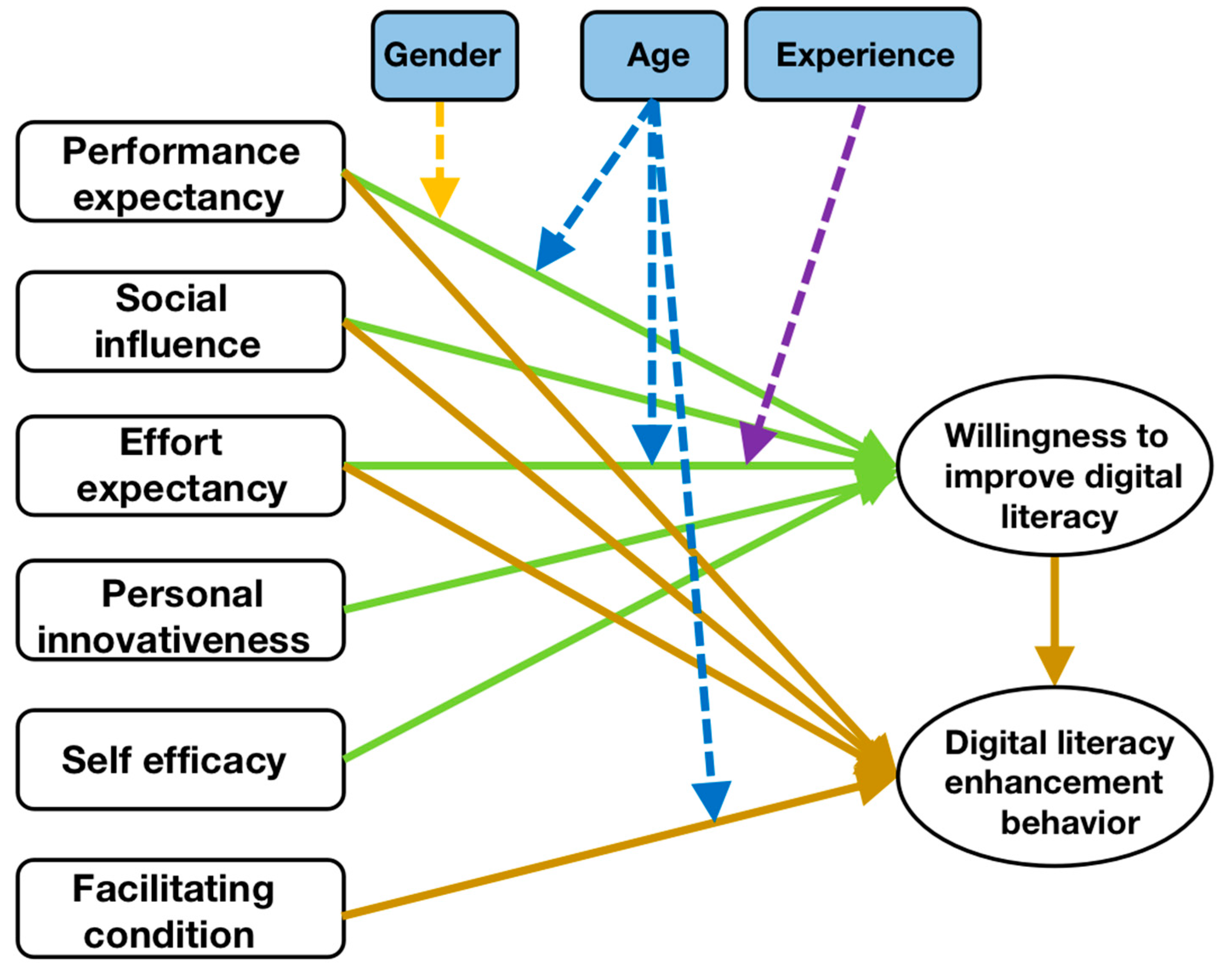

Table 9, it can be seen that the standardized coefficient of the interaction term between tea farmers' gender and performance expectancy on their willingness to improve digital literacy is 0.217, p<0.05. The gender of tea farmers plays a positive moderating role in the impact of performance expectancy on their willingness to improve digital literacy, assuming H13 is valid. The significant p-values corresponding to the interaction terms of gender, social influence, and effort expectancy of tea farmers are greater than 0.05, assuming that H14 and H15 are not valid. The standardized coefficient of the interaction between the age and performance expectancy of tea farmers on their willingness to improve digital literacy is 0.200, the standardized coefficient of the interaction between age and effort expectancy on their willingness to improve digital literacy is 0.183, and the standardized coefficient of the interaction between age and facilitating condition on their willingness to improve digital literacy is 0.097, with significance p-values less than 0.05. This indicates that the age of tea farmers plays a positive moderating role in the impact of performance expectancy and effort expectancy on tea farmers' willingness to improve digital literacy, and that age plays a positive moderating role in the impact of facilitating condition on tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior. Assuming H16, H18, and H19 are valid. The significant p-value corresponding to the interaction between the age and social influence of tea farmers is greater than 0.05, assuming that H17 is not valid. The significance p-value of the interaction term between the experience of tea farmers and social influence is greater than 0.05, assuming that H20 is not valid. The standardized coefficient of the interaction between experience and effort expectancy on the willingness to improve digital literacy is 0.119, with a significance p-value less than 0.05, indicating that the experience of tea farmers plays a positive moderating role in the impact of effort expectancy on their willingness to improve digital literacy. Assuming H21 is valid. The significance p-value of the interaction term between the experience and facilitating condition of tea farmers is greater than 0.05, assuming that H22 is not valid.

Figure 4 is the final model of the influencing factors on the digital literacy improvement behavior of moderate scale tea farmers.

6. Discussion

This study is based on the UTAUT theoretical model, Personal innovativeness theory, and Self-efficacy theory to construct an influencing factor model for tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior. The model is validated through questionnaire data collection, and the following discussions are conducted:

6.1. Mechanism Discussion on the Direct Influencing Factors of Tea Farmers' willingness to Improve Digital Literacy

Performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, personal innovativeness, and self-efficacy all significantly positively affect the willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy. Social influence has the greatest impact on the willingness to improve digital literacy, with a path coefficient of 0.226, followed by self-efficacy, effort expectancy, performance expectancy, and personal innovativeness, with path coefficients of 0.224, 0.178, 0.157, and 0.155, respectively. This indicates that the willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy will increase with the increase of social influence, self-efficacy, effort expectancy, performance expectancy, and personal innovativeness. At the same time, the following five points can be analyzed. Firstly, if the government vigorously promotes and popularizes the development concept of the smart tea industry, empowers tea farmers to enhance their understanding of the development of the tea industry through digital intelligence, and has the opportunity to access the application of smart tea industry equipment and technology. At the same time, tea industry experts provide support and affirmation for tea farmers to improve their digital literacy, and their family and friends support or encourage them to improve their digital literacy, it will enhance their willingness to improve their digital literacy. Secondly, tea farmers have a high sense of self-efficacy and will have strong confidence. They will not feel anxious about the acceptance of new knowledge and technology, and will not stop due to difficulties in improving their digital literacy. Instead, they will become more courageous and enjoy it (Ullah et al., 2022; Aarsand, 2022). Thirdly, tea farmers receive training in digital literacy. If they can find ways to improve their digital literacy and perceive that mastering digital knowledge and skills is not too difficult, they will strengthen their own efforts and expectancy, thereby enhancing their willingness to improve their digital literacy. Fourthly, when tea farmers learn about improving their digital literacy and are able to better engage in tea related work, apply the smart agriculture model for intelligent management of tea gardens, improve tea production efficiency and quality, and use digital platforms to sell tea to increase income and obtain valuable information, it will enhance their willingness to improve their digital literacy (Marcu et al., 2020; Ayu and Satoshi, 2022). Fifthly, tea farmers with strong individual innovation can have a strong interest in agricultural digitization and intelligent technology, and have a strong ability to actively learn emerging agricultural technologies, and tend to try to apply them. The willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy will be enhanced by the enhancement of individual innovation (Al-Qallaf and Al-Mutairi, 2016).

6.2. Mechanism Discussion on Factors Influencing Tea Farmers' Digital Literacy Improvement Behavior

Facilitating condition significantly positively affect the improvement behavior of tea farmers' digital literacy, indicating that if tea farmers have certain economic capabilities, the government provides policy support or training subsidies for the improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy, participating in digital literacy training can effectively improve their digital knowledge and skills, and they can seek help from others when encountering difficulties in mastering digital knowledge and skills, which will promote the improvement behavior of tea farmers' digital literacy (Bhaskara and Bawa, 2021).

The willingness of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy has a significant positive impact on their digital literacy improvement behavior, indicating that when tea farmers learn about the benefits of improving their digital literacy, they will be willing to improve their digital literacy and take practical actions. At the same time, it will promote the benefits of improving digital literacy among people around them and affect their attention to the improvement of digital literacy (Khan et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022).

6.3. Discussion on the Mechanism of Indirect Factors Influencing Tea Farmers' willingness to Improve Digital Literacy

Firstly, the willingness of tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy can mediate the effects of performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, personal innovativeness, and self-efficacy on their digital literacy improvement behavior, indicating that tea farmers will think rationally about their own digital literacy improvement (Newton et al., 2020). The performance expectancy, social influence, and effort expectancy of tea farmers have a direct impact on their digital literacy improvement behavior, indicating that when the performance expectancy, social influence, and effort expectancy of tea farmers are strong enough, it will promote digital literacy improvement behavior. For example, when tea farmers discover that improving digital literacy can greatly improve the efficiency and benefits of tea planting, production, and processing, the government, experts, family and friends express their support and affirmation, at the same time when they perceive that it is not difficult to improve their digital literacy, they will take practical actions to improve their digital literacy (Menant et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023).

In this study, the impact of personal innovativeness and self-efficacy of tea farmers on digital literacy improvement behavior was not significant. There may be two possible reasons. Firstly, based on the UTAUT original model, personal innovativeness and self-efficacy, as newly introduced variables, have an uncertain direct impact on behavior after integration with the UTAUT original model. Through empirical analysis, it was found that these two new variables affect the willingness to improve digital literacy and thus affect the improvement behavior. The second is based on the subjective reflection of personal innovativeness and self-efficacy from the perspective of both variables and tea farmers themselves. When tea farmers are unsure whether new digital knowledge and skills will benefit themselves, the difficulty of mastering them, and whether there are references around them, they will not take immediate action to improve digital literacy (Jain et al., 2022).

6.4. Discussion on the regulatory mechanisms of gender, age, and experience

Gender and age have a significant positive moderating effect on the impact of performance expectancy on the willingness to improve digital literacy, indicating that males and older tea farmers tend to consider more about their willingness to improve digital literacy and focus on the practical value that improving digital literacy can bring to themselves.

Gender, age, and experience do not have a significant moderating effect on the social influence on the willingness to improve digital literacy, indicating that tea farmers currently hold a more traditional development philosophy towards the tea industry. Tea farmers of different genders, ages, and experiences are more cautious when facing new agricultural technologies or digital knowledge and skills. Tea farmers will pay more attention to government support, refer to the opinions and attitudes of tea industry experts, based on the opinions of family and friends around, or considering whether there are currently farmers as a reference, make a comprehensive decision on whether to improve digital literacy.

Age and experience have a significant positive moderating effect on the impact of effort expectancy on the willingness to improve digital literacy, while gender has no significant moderating effect on the impact of effort expectancy on the willingness to improve digital literacy of tea farmers. Tea farmers, who are older and have been engaged in tea cultivation and production for a longer time, have accumulated rich experience in various aspects of tea cultivation, production, and management for many years. In the future, if empower and develop various aspects with digital knowledge and skills that match the requirements, it will be a significant change to the traditional development mode in the past. Tea farmers will consider more based on the actual development situation and their own situation, targeted selection of matching modern digital information technology for empowering development, and efforts to participate in relevant training to improve one's digital literacy level, in order to better adapt to future development needs. Tea farmers of different genders do not have significant differences in their educational background, growth environment, and traditional experience accumulated in tea cultivation, production, and management. Improving their digital literacy requires training and corresponding efforts.

Age has a positive and significant moderating effect on the influence of facilitating condition on digital literacy improvement behavior, indicating that older tea farmers hope to receive more support in digital literacy improvement. Learning digital knowledge and skills requires time to adapt and corresponding assistance, not only considering government policy support and training cost subsidies, but also considering the effectiveness of training (Wu et al., 2022). Experience does not have a moderating effect on the influence of facilitating condition on the improvement of digital literacy behavior, indicating that most tea farmers, regardless of the length of time they have been engaged in tea cultivation, accumulate more traditional experience, and there is not much difference between tea farmers. The development of the digital intelligence empowering tea industry is relatively novel for tea farmers, and the facilitating condition required for them to improve their digital literacy will not differ greatly due to different experiences.

7. Conclusion

This study empirically analyzes the influencing factors model of moderate scale operation of tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior, assuming that H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, H9, H10, H11, H12, H13, H16, H18, H19, and H21 have been validated. Based on the empirical analysis results, six strategies to improve tea farmers' digital literacy are proposed to promote their digital literacy improvement and better engage in the intelligent development of the tea industry.

7.1 Transform the development concept of tea farmers and strengthen the social influence of digital intelligence empowering the development of the tea industry

For moderately sized tea farmers, efforts can be made to promote the development model of smart agriculture, guide tea farmers to change their development concepts, shift towards digital and intelligent development, stimulate tea farmers' enthusiasm and initiative in the development of the "digital empowerment" tea industry, encourage tea farmers to attach importance to and improve their digital literacy, and enjoy the dividends of intelligent development of the tea industry in the future, becoming beneficiaries of digital empowerment. For the government, it is possible to collaborate with tea industry research experts to promote and promote practical smart agriculture technologies or tools to tea farmers operating on a moderate scale based on the practical application of smart agriculture technology in the tea industry. This can reduce the burden on the tea industry's planting and production process, reduce planting production and management costs, improve the quality of tea and increase benefits, and promote tea farmers to improve their digital knowledge and skills. Organize the demonstration role of tea planting technology demonstration large households, allowing them to share their experiences and achievements in digital intelligence empowerment development in a visual way, and exchange digital knowledge and skills. Utilizing the advantages of the Internet and new media to build a digital technology exchange and sharing platform for the tea industry, not only expands the promotion of digital and intelligent agricultural technologies, but also creates a good atmosphere for tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy and promote the improvement of their digital literacy.

7.2. Implement differentiated and tiered training strategies to enhance tea farmers' self-efficacy

Implement differentiation strategies based on different individual characteristics of tea farmers, classify and train tea farmers with different levels of digital literacy, otherwise it will result in lower self-efficacy due to inability to adapt to the training content. Adopting a tiered training strategy, starting with simple digital knowledge and skills, and then moving from easy to difficult, tea farmers gradually learn and master from shallow to deep. During the training process, they gain success, happiness, and a sense of achievement, forming a positive motivation and enhancing their self-efficacy. Improve the corresponding operating equipment and equip technical personnel for guidance, so that tea farmers can preliminarily practice the digital knowledge and skills they have learned, deeply realize the value of digital knowledge and skills, personally experience the benefits of improving digital literacy, enhance self-efficacy, and become more confident and motivated to improve digital literacy in the future.

7.3. Expand training types, channels, and forms to enhance tea farmers' expectancy for hard work

The government can collaborate with universities, research institutions, and other parties to establish a digital literacy training team to provide multi-level and personalized digital knowledge and skills training for tea farmers, meet diversified needs, collaborate with universities or research teams to explore more efficient digital literacy training solutions, and collaborate with enterprises to develop smart agriculture related application software or digital technologies that are easy to understand and operate for farmers, to lower the threshold for tea farmers to participate in digitization. Using smartphone terminals as a support, providing remote guidance and assistance for tea farmers to improve their digital literacy, forming a dynamic coordination and assistance mechanism for time and space, and using live streaming, video, or animation to assist tea farmers in clearing difficulties and obstacles. Promote the development of a digital literacy training model that combines online and offline, theory and practice. Guided by the intelligent transformation and development of the tea industry, effectively connect stage training, continuous training, and systematic training for tea farmers, build a "digital tea farmer" training base that integrates industry and education, carry out "field teaching", strengthen the mastery of digital knowledge and skills, and improve the practical level of digital application.

7.4. Promote the inclusive effect and practical value of digital intelligence empowerment, and enhance the performance expectancy of tea farmers

The government or relevant organizations should make tea farmers truly aware of the usefulness and benefits of improving digital literacy in promoting and promoting the development of the digital empowering tea industry. In the process of popularization, specific practical cases can be combined to enhance tea farmers' effective understanding of the development model of smart agriculture, making them aware that having good digital knowledge and skills will help upgrade tea planting, production, and other links, to achieve intelligent management of tea gardens, intelligent equipment can be applied in tea activities and valuable information can be obtained. Through intelligent equipment or technology, benefits such as energy reduction, quality improvement, yield increase, and income increase can be achieved, enhancing the performance expectancy of tea farmers.

7.5. Explore individual innovative tea farmers and cultivate digital talents in the tea industry

The government, tea cooperatives, and tea associations can explore individual tea farmers with high innovation through certain characteristics, encourage them to develop the tea industry through smart agriculture models, and provide policy and financial support for tea farmers to use smart agriculture technology or equipment. Organize tea farmers with high individual innovation to focus on training, improve the training and incentive mechanism for digital talents in the tea industry, hold digital knowledge and skills competitions, select and evaluate digital talents in the tea industry, cultivate a group of tea farmer elites, and leverage the "head goose effect" of such tea farmers to drive surrounding tea farmers to improve their digital literacy, and promote the transformation of tea farmers' digital literacy into productivity and creativity for the intelligent development of the tea industry, Cultivate batch after batch of digital talents for the intelligent development of the tea industry.

7.6. Strengthen policy support and assistance guarantees, optimize the convenient conditions for tea farmers to enhance their digital literacy

The government should strengthen policy support and training cost subsidies for farmers' digital literacy assistance, and encourage economically capable tea farmers to improve their digital literacy. Emphasize the construction of the teaching staff of institutions or organizations that value digital literacy training, provide policy support or subsidies for digital literacy training related institutions or organizations, establish supervision and incentive mechanisms, and provide guarantee and support for tea farmers' digital literacy training. Establish and improve a long-term mechanism for cultivating tea farmers' digital literacy. The improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy is a dynamic and iterative process, coupled with the rapid development of technology. It is necessary to adjust and optimize the digital literacy cultivation mechanism based on the intelligent development process of the tea industry and the status of tea farmers' digital literacy cultivation, in order to create convenience for the improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy. Track and serve the training effectiveness of moderate scale tea farmers, and upgrade and standardize the training based on feedback from tea farmers.

8. Limitations and future studies

Although this study analyzed the influencing factors of tea farmers' digital literacy improvement behavior in moderate scale operation through standardized empirical research methods, summarized the results of empirical research analysis, and proposed corresponding countermeasures for tea farmers' digital literacy improvement based on empirical conclusions, due to limited personal academic research experience and limited time and energy investment in tea farmers' digital literacy research, this study may have the following limitations.

Firstly, there may be shortcomings in the empirical analysis section of this study in terms of variables and measurement of scale dimensions. This study retains the four main variables of the Utaut theoretical model and introduces two new variables: individual innovation and self-efficacy. In addition to the variables involved in this study, there may be other variables that affect the improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy. Although the scale design of the variables fully considers the characteristics of tea farmers and is based on the original scale and relevant literature, but there may be a problem where the setting of question items is not detailed enough.

The second reason is that the scope of the research sample in this study may not be sufficient. The area investigated in this study is Anxi County, the main tea producing county in China. Anxi County is a world-famous tea producing county. At present, the tea industry is gradually developing intelligently. Considering its representativeness, a total of 440 samples were collected through the investigation of 11 major tea towns in Anxi County, although it meets the requirements of structural equation model for the number of samples. However, the research results may be affected to some extent due to the scope of the research area.

In the process of intelligent development of the tea industry, the digital literacy of tea farmers is the key. Improving the digital literacy of tea farmers can better integrate into the intelligent development of the tea industry, and empower the development of the tea industry through digital intelligence. In order to better promote the improvement of tea farmers' digital literacy, combined with the current shortcomings of this study, future research on tea farmers' digital literacy can be further and improved from the following two aspects. Firstly, when conducting research on the influencing factors of tea farmers' willingness and behavior to improve digital literacy, other influencing factors can be explored to investigate whether there are other factors that have an impact on tea farmers' willingness and behavior to improve digital literacy, or investigate whether there are other mediating and moderating variables that have an impact, and conduct more in-depth research on the willingness and influencing factors of tea farmers to improve their digital literacy. Secondly, different tea producing areas may have different characteristics. Future research can expand the coverage of samples and conduct research on tea producing areas in different places, so that the research conclusions can better guide the practice of improving tea farmers' digital literacy.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Construction of modern agricultural and industrial park for Anxi County in Fujian Province, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, China(KMD18003A)” from Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in China.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

Dongkai Lin constructed the theoretical framework and research model of this study, designed a questionnaire, completed data organization and analysis, and wrote the original draft. Jinke Lin provided guidance and suggestions for the logic and writing of the entire article. Bingsheng Fu is responsible for helping with questionnaire collection. Kexiao Xie is responsible for screening and proposing invalid questionnaires. Wanhe Zheng and Linjie Chang are responsible for modifying the format.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cesco Stefano,Sambo Paolo,Borin Maurizio, et al. (2023). Smart agriculture and digital twins:Applications and challenges in a vision of sustainability. European Journal of Agronomy,2023,146.

- Walter A, Finger R, Huber R, et al. (2017). Opinion: Smart farming is key to developing sustainable agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017, 114(24): 6148-6150.

- Disha, G., and Mansaf, A. (2023). Smart agriculture: a literature review. J. Manag. Anal. [CrossRef]

- Jing Shen , Feng-Tzu Huang , Rung-Jiun Chou. (2021). Rural revitalization of agricultural reclamation - experience from Xiping Tea Ancient Town . Land, 2021-09-03 . [CrossRef]

- Eshet Y. (2004). Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of educational multimedia and hypermedia, 2004, 13(1): 93-106.

- Martin A, Grudziecki J, DigEuLit. (2006). Concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in teaching and learning in information and computer sciences, 2006, 5(4): 249-267.

- Alexander B, Adams S, Cummins M. (2016). Digital literacy: An NMC Horizon project strategic brief. The New Media Consortium, 2016.

- Guzman Mendoza Jose Eder,Munoz Arteaga Jaime,Alvarez Rodriguez Francisco Javier. (2016). An Architecture Oriented to Digital Literacy Services: An Ecosystem Approach. IEEE Latin America Transactions,2016,14(5).

- Havrilova L H, Topolnik Y V. (2017). Digital culture, digital literacy, digital competence as the modern educational phenomena. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 2017, 61(5): 1-14.

- Ramírez-Montoya M S, Mena J, Rodríguez-Arroyo J A. (2017). In-service teachers’self- perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course. Computers in Human Behavior, 2017, 77: 356-364. [CrossRef]

- Napal Fraile M, Peñalva-Vélez A, Mendióroz Lacambra A M. (2018). Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’training. Education Sciences, 2018, 8(3): 104.

- Littlejohn, A., Beetham, H., and McGill, L. (2012). Learning at the digital frontier: a review of digital literacies in theory and practice. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar Kozanoglu, D., and Abedin, B. (2020). Understanding the role of employees in digital transformation: conceptualization of digital literacy of employees as a multi-dimensional organizational affordance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. [CrossRef]

- Hackfort, S. (2021). Patterns of Inequalities in Digital Agriculture: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Danhua, P., and Zhonggen, Y. (2022). A Literature Review of Digital Literacy over Two Decades. Educ. Res. Int. [CrossRef]

- Shahrokh, N., Mark, D. R., and Matin, M. K. (2022). Workplace literacy skills—how information and digital literacy affect adoption of digital technology. J. Doc. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Ángel, N., Sánchez-García, J., Mercader-Rubio, I., García-Martín, J., and Brito-Costa, S. (2022). Digital literacy in the university setting: A literature review of empirical studies between 2010 and 2021. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Catherine, A., and Bertrand, A. (2022). Key factors in digital literacy in learning and education: a systematic literature review using text mining. Educ. Inf. Technol. [CrossRef]

- Campanozzi, L. L., Gibelli, F., Bailo, P., Nittari, G., Sirignano, A., Ricci, G. (2023). The role of digital literacy in achieving health equity in the third millennium society: A literature review. Front. Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P., Chaudhary, K., and Hussein, S. (2023). A digital literacy model to narrow the digital literacy skills gap. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Bawden D. (2001). Information and digital literacies: a review of concepts. Journal of documentation, 2001.

- Gou, K., and Wang, L. (2022). Tripartite Evolutionary Game of Agricultural Service Scale Management and Small Farmers' Interests under Government Preferential Policies. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Gilster P. (1997). Digital literacy[M].John Wiley & Sons,Inc.,1997.

- Li, S. Y., and Yuan, Q. J. (2020). UTAUT and its application and prospect in the field of information system research. J. Mod. Informat. 40, 168–177.

- Chen, M., and Liang, Y. K. (2021). Research on user adoption model of open government data-based on UTAUT theory. J. Journal of Modern Information. 41, 160–168. [CrossRef]

- Ronaghi, M.H.; Forouharfar, A. (2020). A contextualized study of the usage of the Internet of things (IoTs) in smart farming in a typical Middle Eastern Country within the context of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Model (UTAUT). Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101415. [CrossRef]

- Von Veltheim, F.R.; Heise, H. (2021). German farmers’ attitudes on adopting autonomous field robots: An empirical survey. Agriculture 2021, 11, 216. [CrossRef]

- Beza, E.; Reidsma, P.; Poortvliet, M.; Misker Belay, M.; Bijen, B.S.; Kooistra, L. (2018). Exploring farmers’ intentions to adopt mobile short message service (SMS) for citizen science in agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 295–310. [CrossRef]

- Narine, L.K.; Harder, A.; Roberts, T.G. (2019). Farmers’ intention to use text messaging for extension services in Trinidad. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 293–306.

- Michels, M.; Bonke, V.; Musshoff, O. (2020). Understanding the adoption of smartphone apps in crop protection. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 1209–1226.

- Molina-Maturano, J.; Verhulst, N.; Tur-Cardona, J.; Güereña, J.T.; Gardeazábal-Monsalve, A.; Govaerts, B.; Speelman, S. (2021). Understanding smallholder farmers’ intention to adopt agricultural apps: The role of mastery approach and innovation hubs in Mexico. Agronomy 2021, 11, 194.

- Li Qin, Li Yi, Hao Shujun. (2019). Classification estimation of moderate scale management of agricultural land - based on calculations in different regions under different terrains. Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Economic Management, 2019,18 (01): 101-109.

- Fu Lei, Sun Tong, Fang Shiming. (2021). Research on the Factors Influencing the Expansion of Tea Business in Anhui Province . Tea Communication, 2021,48 (01): 153-160.

- Hall B F, Leveen E P. (1978). Farm size and economic efficiency: The case of California. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 1978, 60(4): 589-600.

- Yu Liu,Binjian Yan,Yue Wang,Yingheng Zhou. (2019). Will land transfer always increase technical efficiency in China?—A land cost perspective. Land Use Policy,2019,82.

- Venkatesh V,Morris M G,Davis G B, et al. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly,2003,27(3):425-478.

- MIDGLEY D, DOWLING G R. (1978). Innovativeness: The concept and its measurement. Journal of Consumer Research, 1978, 4 (4): 229-242. [CrossRef]

- Rogers Everett M.,Adhikarya Ronny. (1979).Diffusion of Innovations: An Up-To-Date Review and Commentary. Annals of the International Communication Association,1979,3(1).

- Agarwal R, Prasad J. (1998). The Antecedents and Consequences of User Perceptions in Information Technology Adoption. Decision Support Systems, 1998, 22(1):15-29. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review,1977,84(2).

- LIMA E,HOPKINS T R,GURNEY E,et al. (2018). Drivers for precision livestock technology adoption:a study of factors associated with adoption of electronic identification technology by commercial sheep farmers in England and Wales.PLo S ONE,2018,13(1):e0190489: 1-17.

- Xie Kexiao, Zhu Yuerui, Ma Yongqiang, et al. (2022). Willingness of Tea Farmers to Adopt Ecological Agriculture Techniques Based on the UTAUT Extended Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,2022,19(22).

- Davis F D. (1989). Perceived usefulness,perceived ease of use,and useracceptance of information technology.MIS Quarterly,1989,13(3):319-340.

- Zscheischler Jana,Brunsch Reiner,Rogga Sebastian,et al. (2022). Perceived risks and vulnerabilities of employing digitalization and digital data in agriculture–Socially robust orientations from a transdisciplinary process. Journal of Cleaner Production,2022,358.

- Van Raaij E M,Schepers J J L. (2008). The acceptance and use of a virtual learning environment in China.Computers&Education,2008,50(3):838-852.

- Tom Buchanan,Phillip Sainter,Gunter Saunders. (2013). Factors affecting faculty use of learning technologies: implications for models of technology adoption. J. Computing in Higher Education,2013,25(1). [CrossRef]

- A. C. Obienu , F. I. Amadin. (2020). Education and Information Technologies.2020-10-01. [CrossRef]

- Bandura Albert,Cervone Daniel.(1986). Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,1986, 38(1).

- TSAI H S, LAROSE R. (2015). Broadband Internet adoption and utilization in the inner city:a comparison of competing theories. Computers in human behavior, 2015, 51(10):Part A:344-355.

- Kundu Arnab,Bej Tripti,Dey Nath Kedar. (2021). Investigating Effects of Self-Efficacy and Infrastructure on Teachers' ICT Use, an Extension of UTAUT. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies (IJWLTT),2021,16(6).

- Angel Herrero Crespo, Ignacio Rodriguez del Bosque. (2010). The influence of the commercial features of the Internet on the adoption of e-commerce by consumers. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,2010,(9):562-575. [CrossRef]

- Ahikiriza Elizabeth,Wesana Joshua,Van Huylenbroeck Guido,et al. (2022). Farmer knowledge and the intention to use smartphone-based information management technologies in Uganda. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture,2022,202.

- TURNER A M, TAYLOR J O, HARTZLER A L, etc. (2021). Personal health information management among healthy older adults: Varying needs and approaches [J]. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 2021, 28(2): 322-333.

- Anil Gupta, Anish Yousaf, Abhishek Mishra. (2020). How pre-adoption expectancies shape post-adoption continuance intentions: An extended expectation-confirmation model. International Journal of Information Management,2020,52. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Weiwei. (2020). A Study on the User Acceptance Model of Artificial Intelligence Music Based on UTAUT. Journal of the Korea Society of Computer and Information,2020,25(6).

- Bollen Kenneth A, Lilly Adam G, Luo Lan. (2022). Selecting scaling indicators in structural equation models (sems). Psychological methods,2022.

- Ros, E.X.R.; Field, A. (2006). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006; Volume 37, pp. 189–196.

- Bontis, N.; Crossan, M.M.; Hulland, J. (2002). Managing an organizational learning system by aligning stocks and flows. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 437–469. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Trivedi, H.; Yadav, R.; Das, B.; Bist, A.S. (2016). Effect of drip irrigation on yield and water use efficiency on brinjal (Solanum melongena) cv. Pant samrat. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Res. Technol. 2016, 5, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. J. Psychological Bulletin 103, 411–423.

- Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, J.B.; Zeng, Y.M. (2018). Rural households’ willingness to accept compensation for energy utilization of crop straw in China. Energy 2018, 165, 562–571. [CrossRef]

- Nejadrezaei, N.; Sadegh Allahyari, M.; Sadeghzadeh, M.; Michailidis, A.; El Bilali, H. (2018). Factors affecting adoption of pressurized irrigation technology among olive farmers in Northern Iran. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 190. [CrossRef]

- Rusere, F.; Crespo, O.; Dicks, L.; Mkuhlani, S.; Francis, J.; Zhou, L. (2019). Enabling acceptance and use of ecological intensification options through engaging smallholder farmers in semi-arid rural Limpopo and Eastern Cape, South Africa. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 44, 696–725. [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.F.; Mohammad, K.-K.; Hamid, E. Bilali. (2020). Attitude components affecting adoption of soil and water conservation measures by paddy farmers in Rasht County, Northern Irfan. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104885.

- He, K.; Zhang, J.B.; Zeng, Y.M. (2020). Households’ willingness to pay for energy utilization of crop straw in rural China: Based on an improved UTAUT model. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111373. [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M.; Gutierrez, L. (2022). Micro-irrigation technology adoption in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon: A behavioural model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7685. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Ullah, S., Kiani, U. S., Raza, B., and Mustafa, A. (2022). Consumers’ Intention to Adopt m-payment/m-banking: The Role of Their Financial Skills and Digital Literacy. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Aarsand, P. (2022). Categorization Activities in Norwegian Preschools: Digital Tools in Identifying, Articulating, and Assessing. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Marcu, I., Suciu, G., Bălăceanu, C., Vulpe, A., and Drăgulinescu, A. (2020). Arrowhead Technology for Digitalization and Automation Solution: Smart Cities and Smart Agriculture. Sensors. [CrossRef]

- Ayu, W., and Satoshi, N. (2022). Exploring the characteristics of smart agricultural development in Japan: Analysis using a smart agricultural kaizen level technology map. Comput. Electron. Agric. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qallaf, C. L., and Al-Mutairi, A. S. R. (2016). Digital literacy and digital content supports learning. The Electronic Library. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskara, S., and Bawa, K. S. (2021). Societal Digital Platforms for Sustainability: Agriculture. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. A., Qijie, G., Sertse, S. F., Nabi, M. N., and Khan, P. (2019). Farmers’ use of mobile phone-based farm advisory services in Punjab, Pakistan. Inf. Dev. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. J., Hyung, J. A., and Han, H. (2022). Health literacy and health care experiences of migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Newton, J. E., Nettle, R., and Pryce, J. E. (2020). Farming smarter with big data: Insights from the case of Australia's national dairy herd milk recording scheme. Agric. Syst. [CrossRef]

- Menant, L., Gilibert, D., and Sauvezon, C. (2021). The application of acceptability models to Human Resource Information Systems: A literature review. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Garg, N., and Khera, S. N. (2022). Adoption of AI-Enabled Tools in Social Development Organizations in India: An Extension of UTAUT Model. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Zhang, B., Li, S., and Liu, H. (2022). Exploring Factors of the Willingness to Accept AI-Assisted Learning Environments: An Empirical Investigation Based on the UTAUT Model and Perceived Risk Theory. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Jia, J., and Wu, C. (2023). Factors influencing the behavioral intention to use contactless financial services in the banking industry: An application and extension of UTAUT model. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).