1. Introduction

The 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as the 169 targets are integrated and invisible, and thus demonstrate the holistic view of this universal 2023 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SD) and align with the three perspectives of SD, according to Fonseca, Carvalho and Santos (2023) [

1] as well as other authors [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The sustainability of people, organizations and the planet is a topic increasingly on everyone's agendas. Sustainability, Sustainable Development (SD) and Project Management (PM) have been the main topics of discussion among researchers [

6]. Jensen et al. (2016) [

7] state that projects are becoming a key fundamental factor for economic and social action. According to Vrchota et al. (2021) [

8] sustainability is an integral part of PM practices that maintain the future benefits of the Triple Bottom Line (economic, environmental, and social). Silvius (2017) [

9] states that sustainability has become an established school of thought in PM. However, current best practice in PM does not consider environmental sustainability [

10,

11].

Existing PM methodologies are poorly developed in terms of sustainability and there are few scientific publications relating PM to sustainability. This article aims to help fill this gap by broadening the debate on sustainability in PM and comparing two relatively new PM methodologies - PM² and PRiSMTM - in terms of their approach to sustainability.

This article aims to analyze the presence of sustainability in PM in some PM guides and in scientific publications, obtained through the SCOPUS database. In addition, it was also chosen to study a relatively recent methodology related to sustainability, PRiSMTM., It was decided to study this methodology alongside another methodology, PM², to serve as a baseline for comparison. Thus, a comparison was made between these two methodologies based on their guides and scientific publications. In the search for publications on the PRiSMTM methodology, the P5™ standard was included, since PRiSMTM is based on it.

This article is divided into six sections. In the introduction, section 1, a brief reference is made to the motivations behind the work, as well as the importance of the topic. Next, materials and methods, section 2, includes the research methodology and methodological process, setting out the process used to locate, select, evaluate and analyze the available studies.

Section 3 is dedicated to the theoretical background, with a literature review presenting the basic concepts that underpin this study. The next section, 4, is dedicated to presenting the results regarding the occurrence of the term "sustainability" and the analysis of PM² and PRiSM

TM methodologies. Finally, section 5 presents a discussion of the main findings and section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the research methodology and the methodological process used for the analysis of the occurrence of the term "sustainability" in PM guides as well as in scientific publications and the process used for the analysis of the PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies in scientific publications and through interviews (in the case of the PM² methodology). This study aims to fill the gap in studies related to sustainability in PM and broaden the debate on the subject. It was decided to study a relatively recent sustainability-related PM methodology, PRiSM, in conjunction with another methodology. The second methodology chosen for the analysis was PM², as it is also a relatively recent methodology developed by the European Commission and open to all.

According to Stanitsas et al. (2021) [

12], many studies present cases regarding the need for PM to evolve on the sustainability path, especially in some more specific sectors, such as industry and construction [

13]. The same author, Stanitsas et al. (2021) [

12], states that Silvius (2017) [

14] makes an argument in which he claims that traditional PM (predictive methodologies) doesn't successfully address the basic principles of sustainability as presented in the TBL (Triple Bottom Line) scenario - society, environment and economy.

2.1. Research Methodology

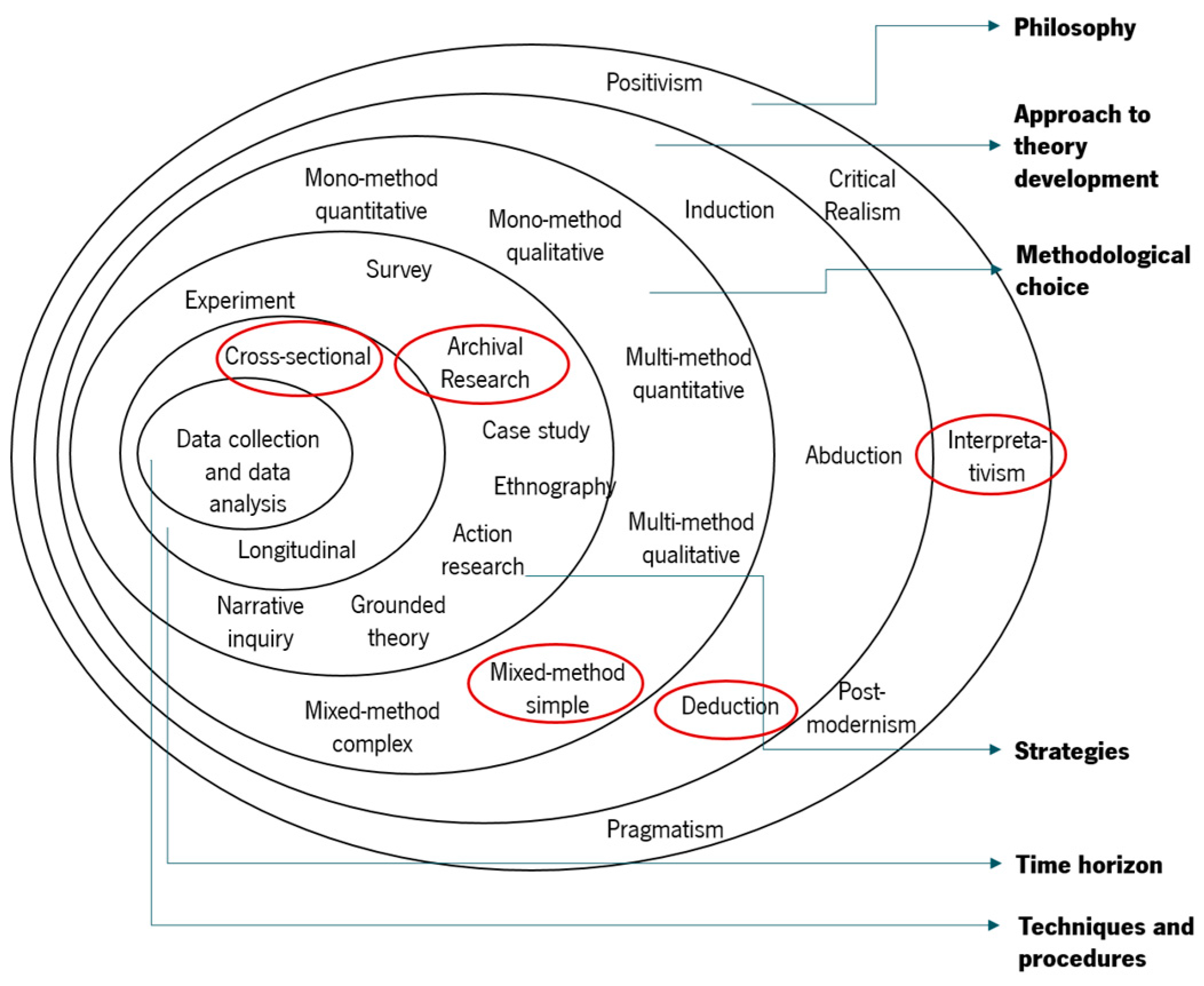

As depicted in the research onion of Saunders et al. (2019) [

15], shown in

Figure 1, the research methodology of this work has the following characteristics:

Philosophy: interpretativism;

Approach to theory development: deduction;

Methodological choice: mixed-method simple;

Strategies: archival research;

Time horizon: cross-sectional.

Techniques and procedures: literature review and analysis, interviews.

Therefore, initially, in this study, a review of the state of the art was carried out on the main topics related to this research project to produce the theoretical background using Scopus, Elsevier, B-on and Google Scholar databases. Then, the number of occurrences of the word “sustainability” in various PM guides was analyzed. After that, the presence of the term sustainability in academic publications and over the years was verified through a search and analysis carried out in the SCOPUS database. Next, the PM² and PRiSMTM methodology guides were analyzed. Also, articles that included the PM² and PRiSMTM methodology and the P5™ standard, found in various databases (Scopus, Web of Science and B-on), were analyzed, from which the features associated with each of them were drawn. It was the researchers' option to include the P5™ standard in the research since the PRiSMTM methodology is based on it.

The methodological process of Systematic Literature Review [

17] was used in the analysis of PM² and PRiSM

TM methodologies based on scientific publications, in a structured way of search and analysis for the collection of the maximum number of articles (valid and relevant), as recommended by Laursen and Svejvig (2016) [

18]. Two interviews were also done to confirm some of the findings based on archival research and to collect opinions.

2.2. Methodological Process

The methodological process is divided into two subsections: i) the occurrence of the term "sustainability" (sustainability in PM guides and sustainability in PM in scientific publications); and ii) PM² and PRiSMTM (PM² and PRiSMTM in scientific publications and PM² interviews). This section will explain the basis and methods used to obtain the results presented in the following chapter, section 3.

2.2.1. The occurrence of the term "sustainability"

In the study of the occurrence of the term "sustainability" it was decided to study this topic in PM guides and scientific publications. This section describes the methods used to obtain the results presented below in section 3.2, which is divided into two sub-sections: i) sustainability in PM guides; and ii) sustainability in PM in scientific publications.

Sustainability in PM guides

Silvius (2017) [

14] argues that traditional PM, namely predictive methodologies, do not successfully address the basic principles of sustainability, i.e. the TBL.

As a first approach and to verify the extent of the occurrence of the word sustainability in the various PM guides, a search for the term "sustainab*" in the English guides and "sustentab*" and "sustentav*" in the Portuguese guides was conducted, to capture the largest number of words associated with sustainability.

Five guides of traditional PM methodologies/knowledge bodies were used for the search:

Sustainable Project Management – The Green Project Management (GPM

®) Reference Guide, by GPM

® [

19];

Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management, by International Project Management Association [

20];

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge – PMBOK

® Guide by Project Management Institute [

21];

Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2

® by AXELOS [

22];

PM² Methodology Guide by PM² ALLIANCE [

23].

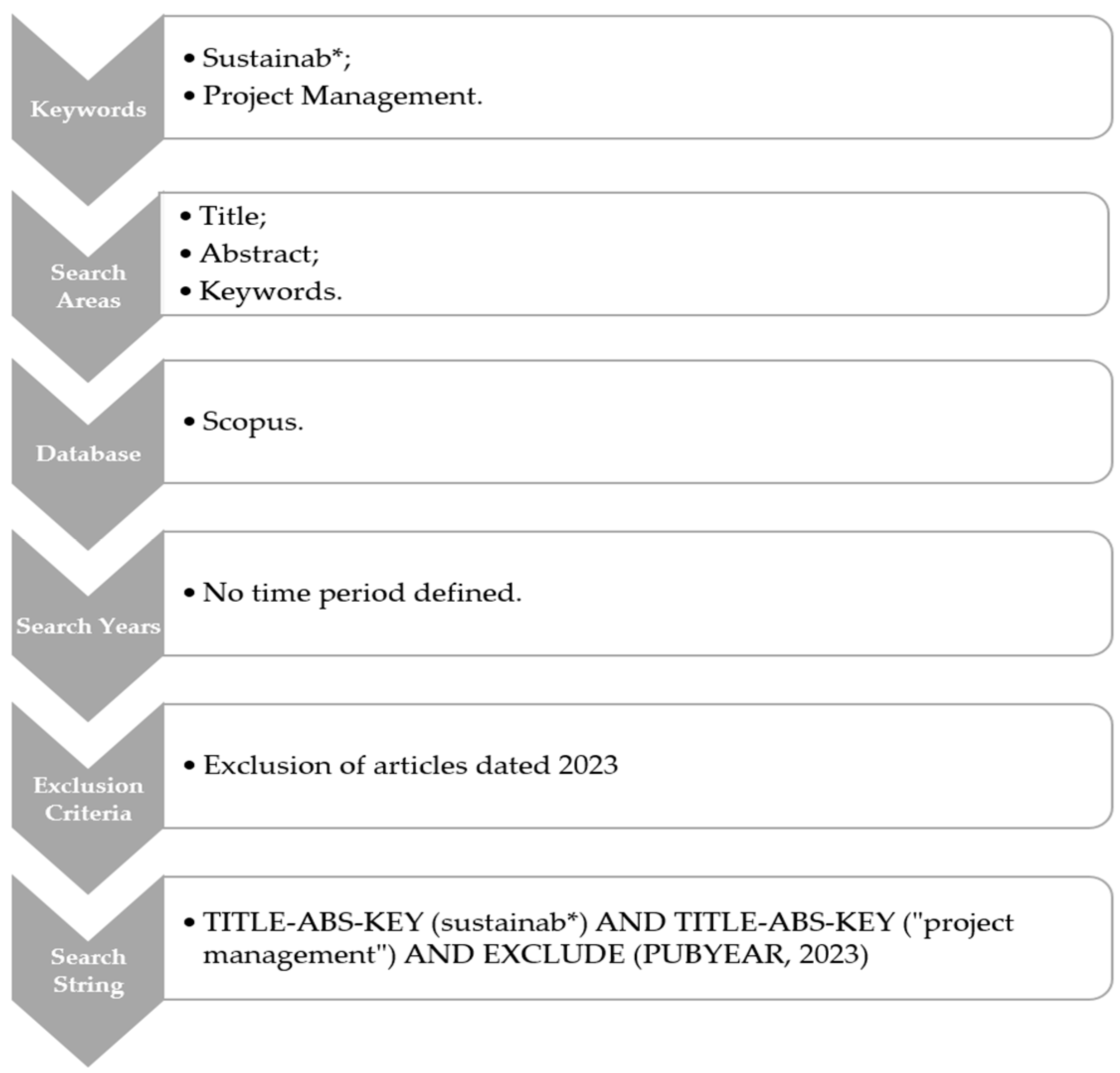

Sustainability in PM in scientific publications

In order to understand the level of dissemination of sustainability in PM around the world and over the years, a search was carried out in just one database to facilitate the process. The database selected was Scopus because of the huge amount of data it captures, its reliability and transparency, and its ease of use. A total of 6769 documents were returned by the SCOPUS database after entering the following search string: TITLE-ABS-KEY (sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("project management") AND EXCLUDE (PUBYEAR, 2023). The search took place in 2022, however, articles with the year 2023 were also returned. Therefore, it was decided to exclude this year from the search.

Figure 2 below shows the search protocol used.

2.2.2. PM² and PRiSMTM

In this section, the publications for the systematic literature review (SLR) on the PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies are selected and the interviews on the PM² methodology are organized. This section describes the methods used to obtain the results presented below in section 3.3, which is divided into three sub-sections: i) analysis based on guides; ii) analysis based on scientific publications; and iii) analysis based on interviews. For the analysis based on guides, only the guides related to the two methodologies under study, PM² and PRiSMTM, were used. The methodological process for the analysis based on scientific publications and interviews is presented below.

PM² and PRiSMTM in scientific publications

The research done previously is essential to identify the state of the art on a particular topic [

24]. According to Donato and Donato (2019) [

25], the SLR allows authors to become knowledgeable about the topic and can develop a range of skills including searching the literature and improving their scientific writing.

According to Furlan et al. (2001) [

26], a SLR answers a specific research question and uses systematic, explicit, and predefined methods to identify, select, and critically evaluate relevant research.

To obtain articles for review on the PM² and PRiSMTM methodology a search was conducted using the SCOPUS, Web of Science and B-on databases.

Given that the PRiSM

TM methodology is based on the P5™ standard, it was decided to include it in the search terms to achieve a larger number of results. The article search period considered was between 2013 and 2022 due to the release dates of the publications. The open edition of the PM² Guide was released in 2016 [

27]. The GPM

® Reference Guide to Sustainability in Project Management, which includes the PRiSM

TM methodology and the P5™ Standard for Sustainability in Project Management, was released in 2013 [

28,

29].

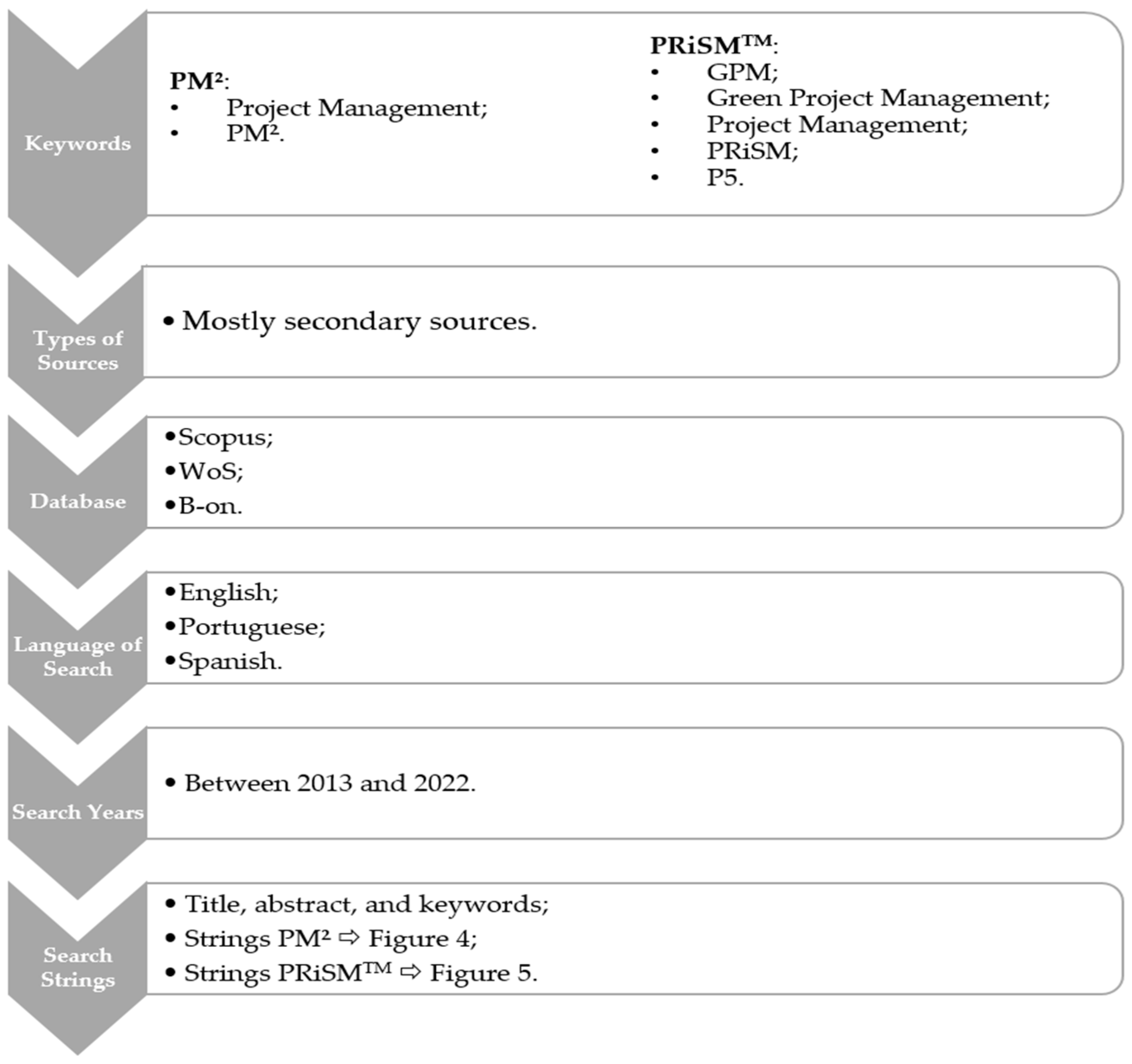

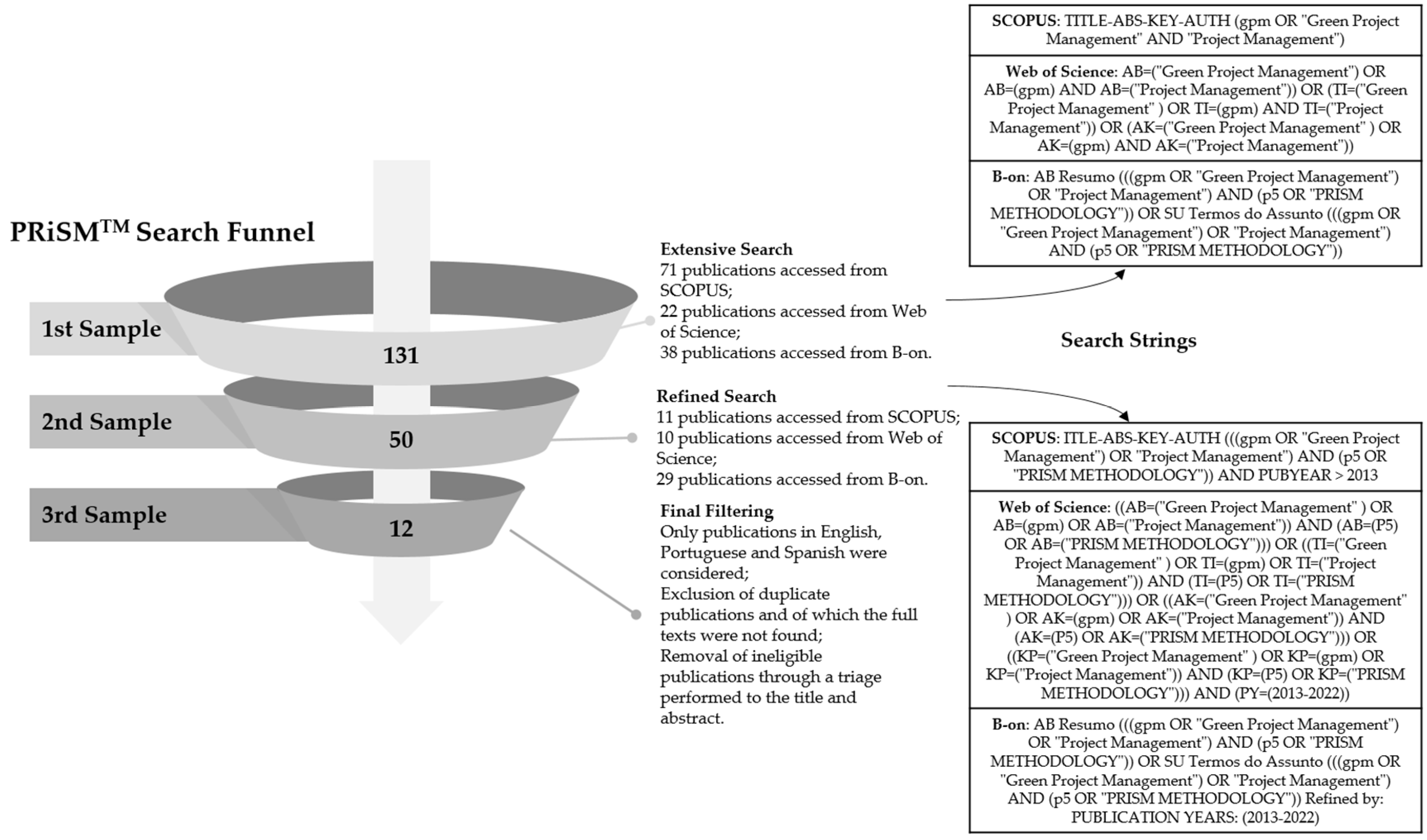

The protocol used in the search is summarized in

Figure 3.

The process and search strings are shown in

Figure 4 for the PM² methodology and in

Figure 5 for the PRiSM

TM methodology. Initially, it was decided to conduct an extensive search that led to the constitution of a 1

st sample of articles. Only the most general terms were used in this search, with no time limits. After that, a refined search was conducted, where the time limits were introduced to the search by changing the strings, considering articles only between 2013 and 2022 and other aspects that were considered important to add, such as the exclusion of the term PM2.5 (since it refers to a different thematic) in the case of the PM² methodology and the insertion of the terms P5 and PRiSM

TM methodology in the case of the PRiSM

TM, leading to the 2

nd sample. Finally, filtering was carried out where some inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, resulting in the final set of papers for analysis. The inclusion criterion applied defined that the publications had as their main subject the keywords described above in

Figure 3. The exclusion criteria applied were the removal of publications that were not in English, Portuguese or Spanish, those that were duplicated, those whose full text was not found and the documents that were not within the scope and did not reflect the main objective of the research by reading the title and abstract.

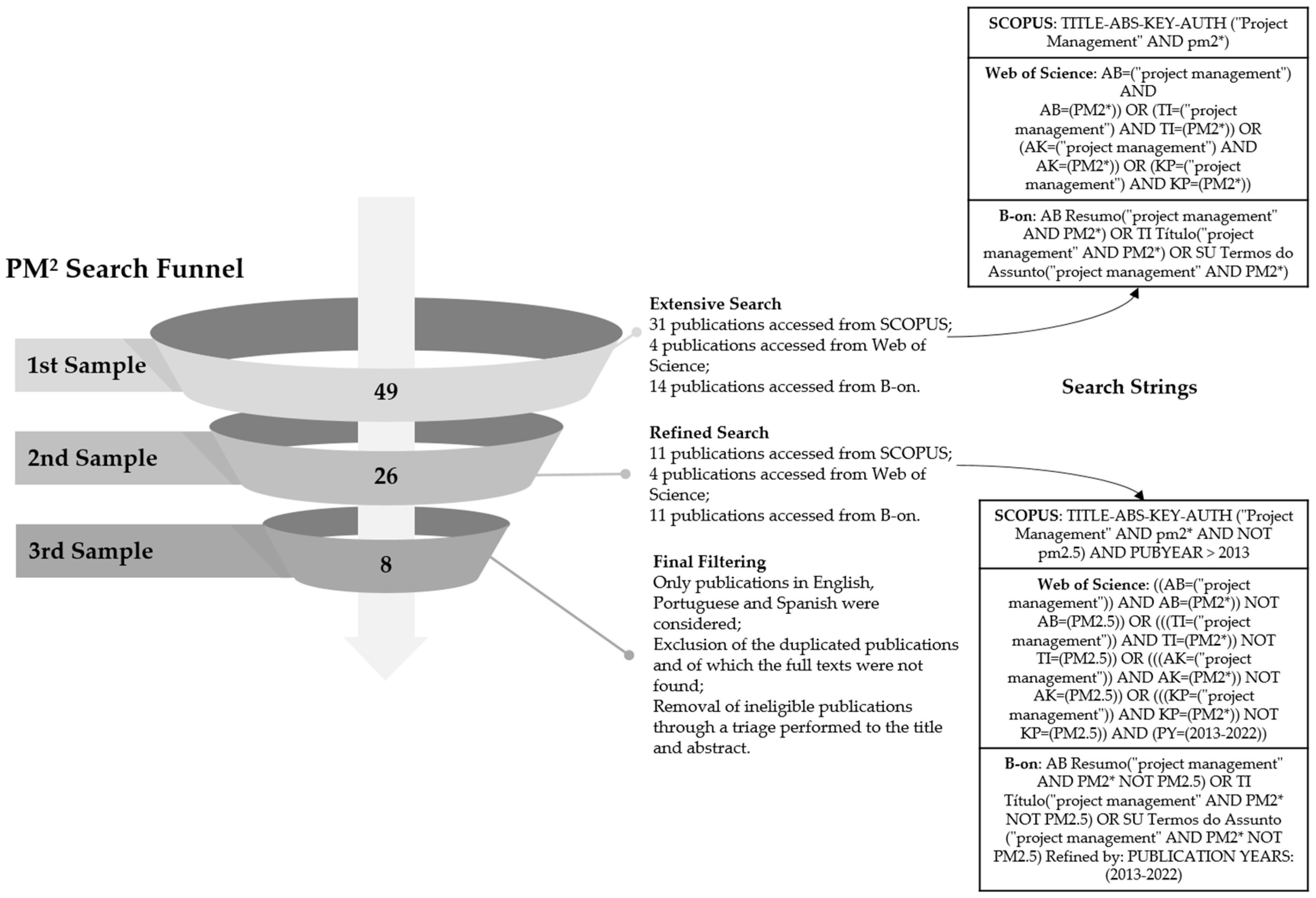

Regarding the PM² search process, as seen in the funnel represented in

Figure 4, an extensive search was performed, from which 31 publications were obtained through SCOPUS, four from Web of Science, and 14 from B-on, totalling 49 publications in the 1

st sample. Next, a refined search was performed, where 11 publications were obtained through SCOPUS, four from Web of Science, and 11 from B-on, completing a total of 26 publications in the 2

nd sample. Lastly, a final filtering was applied (3

rd sample), resulting in a total of eight publications.

Regarding PRiSM

TM search process, as seen in the funnel represented in

Figure 5, an extensive search was performed, from which 71 publications were obtained through SCOPUS, 22 from the Web of Science, and 38 from B-on, totalling 131 publications in the 1

st sample. Next, a refined search was performed, where 11 publications were reached through SCOPUS, 10 from Web of Science, and 29 from B-on, completing a total of 50 publications in the 2

nd sample. Finally, a final filtering was applied (3

rd sample), resulting in a sample of 12 publications to be used in the literature review.

Following the two searches above mentioned, 20 relevant publications to the research project were obtained, eight referring to the PM² methodology and 12 referring to PRiSM

TM. The authors, titles and databases where the documents are founded are shown in

Table A1, in the

Appendix A.

PM² Interviews

The interviews were done following a four-phase process [

30,

31,

32]: i) preparation of the interview; ii) introduction; iii) conducting the interview; and iv) synthesis and conclusion of the interview evaluation.

During the preparation of the interview, the selection of people or entities that have the necessary knowledge to meet the researcher information needs takes place. The researcher should prepare an interview script to have a guide to support conducting the interview. In this stage, the technological means to be used in the interviews should be prepared, as well as the necessary documents to request, for example, authorization to record the interview.

The introduction is the least structured and non-directive phase. This phase should contain the introduction of the subject, the explanation of the researcher's role in the research process, and the presentation of the process to the interviewee.

In conducting the interview, the researcher must obtain, from the interviewees, the information he wants and the phase should consist of two steps. The thematic step, the most in-depth of the interview, in which issues of interest to the study being carried out are addressed. And the mirror step, in which the interviewer clarifies doubts about what was said by the interviewee.

In the synthesis and conclusion of the interview evaluation, the researcher should thank the interviewee for his participation and inform him that the final results of the study, as well as the transcript of the interview, will be sent later.

To understand and explore the knowledge and experience of each of the interviewees concerning the methodologies studied, customized scripts were prepared for each of them, consisting of a range of open-ended questions. The criteria for selecting interviewees were based on their familiarity with the methodology and their pratical experience in applying it to projects, enabling them to provide informed comments – Convenience sampling. The researchers chose to interview a user of the PM² methodology - a researcher who, during the master's thesis research, studied and applied the PM² methodology in the management of projects, - and Nicos Kourounakis - coauthor of the PM² methodology, the Agile PM² Guide and the PfM² Portfolio Management Guide, and president and CEO of the PM² Alliance. The interviews were performed via Zoom platform, allowing recording with the interviewees' permission. Before the interviews were conducted, the interviewees were asked to sign the consent statement for the interview and its recording.

3. Theoretical Background

This chapter presents a literature review of the main concepts related to the themes under analysis – PM, sustainability, sustainability in PM and PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies. The literature review was performed based on a search done on the Scopus, Elsevier, B-on and Google Scholar databases and in the guidebooks.

The literature review process is considered in most cases to be an initial activity that can then be refined throughout the life of the research project. This literature review aims to contextualize the present research in relation to previous research that addresses the same subject. The literature review should analyze the most relevant research on the topic [

16]. In this way, it was decided to review the literature on four themes: i) PM; ii) Sustainability; iii) Sustainability in PM; iv) PM

2 and PRiSM

TM methodologies. The results are presented next.

3.1. Project Management

According to Kerzner (2017) [

33], companies are increasingly starting to consider PM as mandatory for their survival. To better understand the meaning of PM, it is important to start by understanding the meaning of project. Tuman (1983) [

34] defines a project as an organization of dedicated people seeking to achieve a specific purpose and goal. Projects usually involve large, expensive, unique, or high-risk undertakings that must be completed by a certain date, for a certain amount of money, within some expected level of performance. At a minimum, all projects need to have well-defined objectives and sufficient resources to accomplish all necessary tasks.

Once the concept of a project is understood, another concept should be defined: PM. Kerzner (2017) [

35] considers that PM consists of planning, organizing, guiding, and controlling the resources of a company, in a limited time, to achieve specific goals and objectives.

In addition to these definitions, there are many others in the literature. For a better understanding of the project and PM concepts,

Table 3 was prepared, with their definitions according to well-known PM standards.

After understanding these two concepts, it is possible to verify and agree with the statement of Munns and Bjeirmi (1996) [

40], which argue that the project relates to the definition and selection of a task that will generate future benefits for the company, while the PM is more concerned with planning and control.

In addition to, Wagner (2020) [

41], highlights the changes in the world of work that have led projects to become a crucial way to implement innovations, techniques and organizational changes efficiently. According to Wagner (2020) [

42], Midler's (1995) [

43] article coined the word "projectization" describing it as the diffusion of projects as a form of business organization. Midler (1995) uses the term "projectization" to describe the evolution and organizational changes of Renault, which transitioned from a classic functional organization (1960s) to project coordination (1970s) and to autonomous and powerful project teams (1989). According to Jensen et al. (2016) [

44] projects have become a key factor and vehicle for economic and social action.

Finally, Bourne et al. (2023) [

45], referring to the existence of a misalignment between goals and governance, highlight the need to use governance to guide the project over time.

3.2. Sustainability

Sustainable Development (SD) has been on the United Nations (UN) agenda for more than 40 years, since the first conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 [

46]. In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development defined the concept of SD as development that meets the existing needs of current generations without compromising the needs of future generations [

47]. However, some authors highlight that this definition doesn't provide good guidance on how to identify present and future needs, the technologies and resources needed to meet these needs and how to effectively balance organizational responsibilities for the various stakeholders, which makes this definition difficult to apply in practice for organizations [

48,

49]. Furthermore, this definition encompasses social, environmental and economic issues that are generally operationalized through the TBL [

50]. TBL is a SD concept that integrates three dimensions: profit, planet and people [

51].

Figure 6 shows the interconnection of the various elements of this concept and their definitions.

Figure 6 shows that people represent the social variables, profit represents the economic variables and planet represents the environmental variables.

According to Schieg (2009) [

53], TBL is a new understanding of the success of organizations, where their performance must strike a balance between economic, ecological and social criteria. This new understanding suggests that companies should be dedicated not only to socially and environmentally responsible behaviour but also to achieving positive financial gains [

54].

The United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, in 2001, developed SD indicators that encompass guidelines and methodologies to guide decision-making [

55]. Gladwin et al. (1995) [

56] describe SD as a process to achieve human development in an inclusive, connected, equitable, prudent and safe manner. The European Commission describes Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a concept under which companies integrate social and environmental concerns into their operations and interaction with their stakeholders voluntarily [

57].

A survey conducted by the UN Global Compact on Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability concludes that CEOs believe in a new era of sustainability, which encompasses a new way of assessing corporate performance. In this new era, the focus will shift to long-term value creation, involving social and environmental impact, and away from just financial profit and loss [

58].

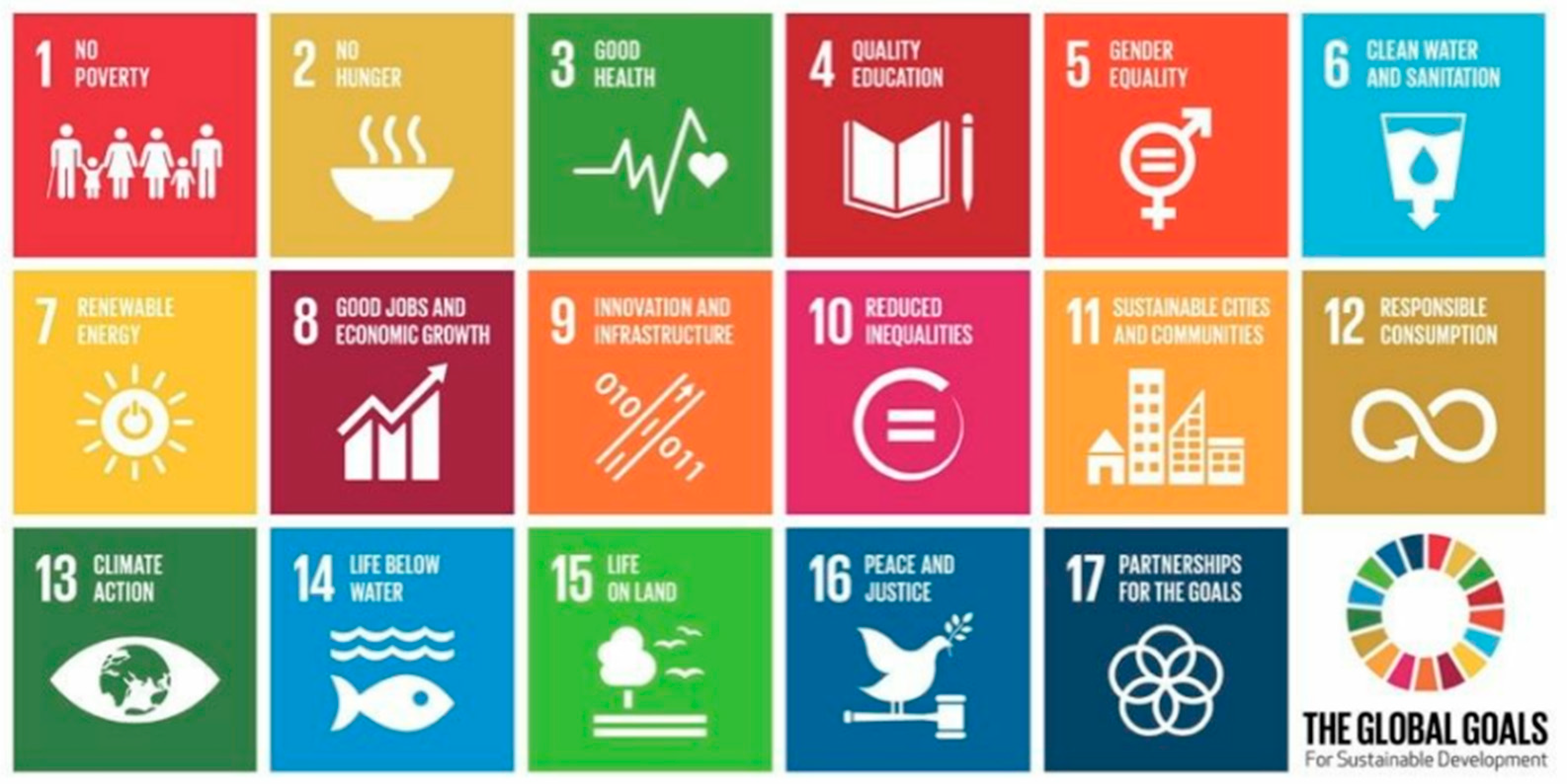

In 2015, the 2030 Agenda defined the 17 SDGs, represented in

Figure 7 [

59].

These SDGs and the targets set were intended to stimulate action for the next 15 years, through an action plan that acts in five key dimensions [

60]:

People - seeks to end poverty and hunger;

Planet - involves meeting present and future needs, but protecting the planet from degradation;

Prosperity - seeks to ensure that all human beings have a prosperous and fulfilling life;

Peace - seeks just, peaceful, inclusive societies, free from fear and violence;

Partnership - seeks the means necessary to implement this Agenda.

Projects generally affect sustainability both directly (by creating pollution and misusing resources) and indirectly (by creating products and/or services that indirectly affect sustainability) [

61]. The study "Insights on Sustainable Project Management", carried out by GPM

®, observed that 96% of respondents believe that projects and PM are essential for SD [

62].

Tsalis et al. (2020) [

63] claim that the pressure on companies to report on sustainability strategies has been increasing. According to the author, many companies have adopted strategies to achieve SD goals.

In 2019, the European Green Deal was presented in Brussels as a way forward to achieve a sustainable economy in the European Union. This pact aims to eliminate net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, making Europe the first climate-neutral continent [

64].

3.3. Sustainability in Project Management

Carvalho and Rabechin (2017) [

65] and Ivanov et al. (2020) [

66] state that it was only in 2010 that the link between PM and sustainability began. However, for other authors, this link started earlier [

12,

67,

68]. Stanitsas et al. (2021) [

12] state that sustainability, SD and PM have become the main topics of discussion among researchers in recent years. For Sabini et al. (2019) [

69], sustainability influences traditional PM tools, techniques and methodologies. Huemann and Silvius (2017) [

70] highlight the importance of PM concerning the SD of organizations and society.

Kerzner (2017) [

35] argues that the result (and success) of a project has moved from being just a delivery, to the creation of business value in a sustainable way. However, there is a lack of a framework that enables the analysis and assessment of sustainability, i.e., a useful and applicable method for projects [

71,

72,

73].

Kerzner (2017) [

35] presents a future definition of the concept of project - a collection of sustainable business value scheduled for realization; programme - a collection of projects designed to achieve a business objective and create sustainable business value within established competing constraints; and success - achieving the desired business value within competing constraints [

35]. PM's role is to identify relevant ecological systems, recognize the internal and external dimensions of social responsibility and test existing Corporate Social Responsibility standards for their applicability in projects [

74].

In PM, Corporate Social Responsibility means a systematic combination of interest in the project with interest in the public welfare [

74]. For PM to add value to projects, it needs to take into account ecological and social aspects [

74]. Eskerod and Huemann (2013) [

75], consider that project stakeholder management in a SD context is a necessity in the future. However, PM standards do not explicitly take into account SD principles [

76].

Silvius and Schipper (2014) [

77] consider that sustainable PM takes into account the environmental, economic and social aspects of the life cycle of project resources, processes, deliverables and effects. However, some authors, [

78,

79,

80], consider that there is a lack of a common framework and language to analyze and assess sustainability that can be applied to projects [

78,

79,

80]. Schieg (2009) [

74] and Goedknegt and Silvius (2012) [

81] stress the importance of project managers taking responsibility for sustainability.

Also Valdes-Vasquez and Klotz (2013) [

82], point out that integrating social considerations of end-users and considerations of the project's impact on society will improve not only the long-term performance of the project but also the quality of life of those affected by the project.

Business leaders are switching from current economic models, which devalue natural resources and only consider profit as the indicator of success, to new models that reward environmentally sustainable products and services [

29].

Although the presence of sustainability in PM events is intense [

70], Brones et al. (2014) [

83] and Silvius and Schipper (2014) [

77] claim that current PM best practices do not consider environmental sustainability. In the same line of thought, Eskerod and Huemann (2013) [

76] state that PM standards do not explicitly consider SD principles. According to Carboni et al. (2018) [

29], PM should make greater efforts to address social and environmental impacts in each project. According to some authors, sustainability has a positive impact on project success [

84,

85,

86]. Other authors enhance the importance of integrating sustainability into methodologies and bodies of knowledge in order to respond to market needs [

87,

88,

89,

90]. On the other hand, A. Silvius and Schipper [

77], argue that performing sustainable management of a project will lead to minimizing waste.

3.4. PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies

This section presents in a nutshell two relatively recent methodologies, PM² and PRiSMTM, which were studied in this research.

3.4.1. PM²

The PM² methodology, developed by the European Commission, aims to “… enable Project Managers (PMs) to deliver solutions and benefits to their organizations by effectively managing the entire lifecycle of their project” [

36] (p. 1). This methodology, although it can be used by any organization, was created to respond to the needs of the institutions and projects belonging to the European Union [

36].

The PM² methodology, according to PM² ALLIANCE (2018) [

36], has the following advantage:

Uses universally accepted PM best practices;

Has a common vocabulary, which allows easy communication and application of the concepts;

Establishes a link to the PM² Agile and PM² Project Portfolio Management models;

Is simple and easy to apply;

Improves the effectiveness of PM;

Provides templates and guidelines for the process and artefacts used.

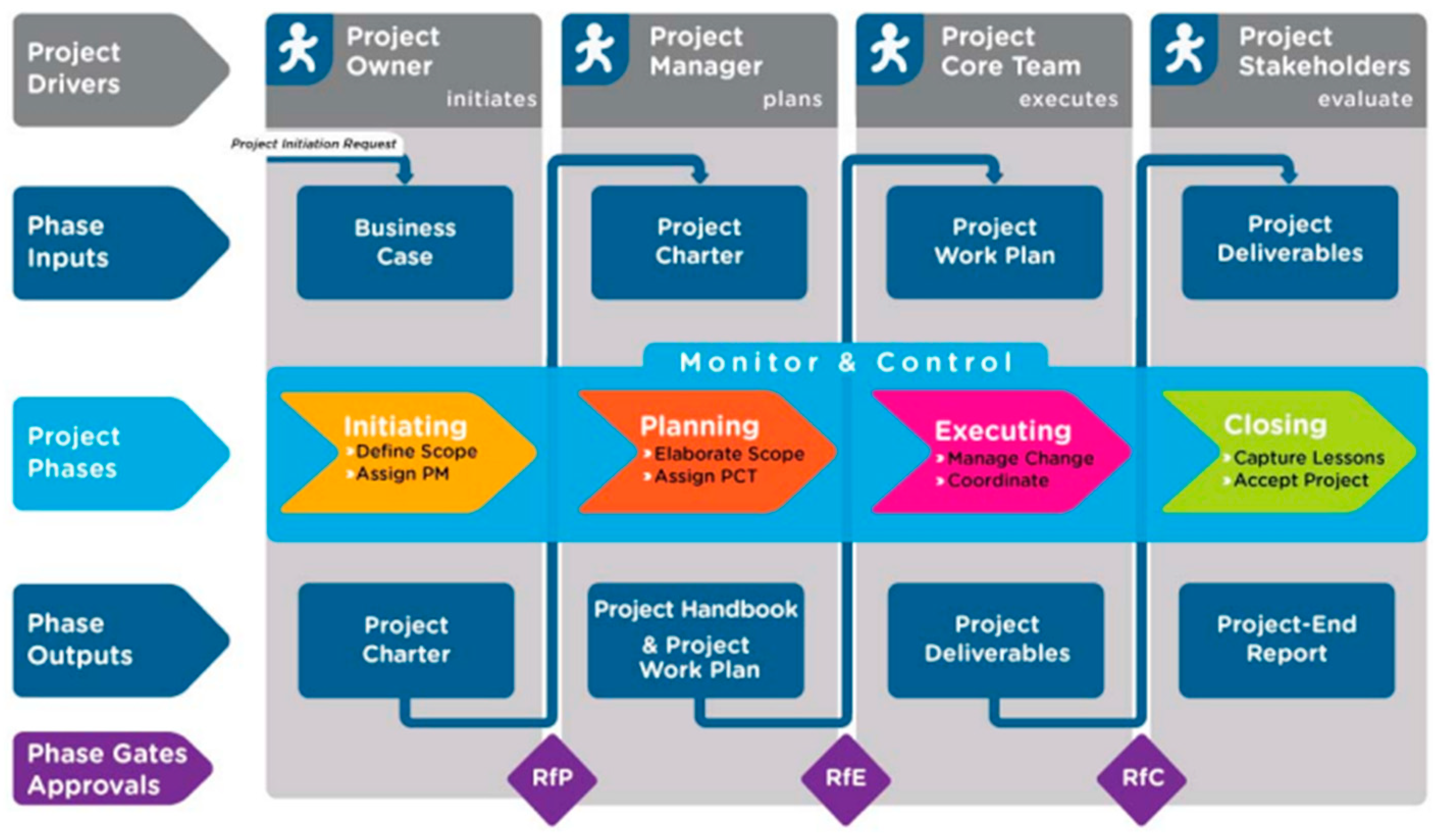

Figure 8 summarizes all phases of the PM² methodology, with the inputs, outputs and key activities of each phase.

The PM² methodology has four phases: Initiation Phase, Planning Phase, Execution Phase and Closing Phase. In addition to these phases, the methodology provides and advocates the use of monitor and control activities throughout the project life cycle.

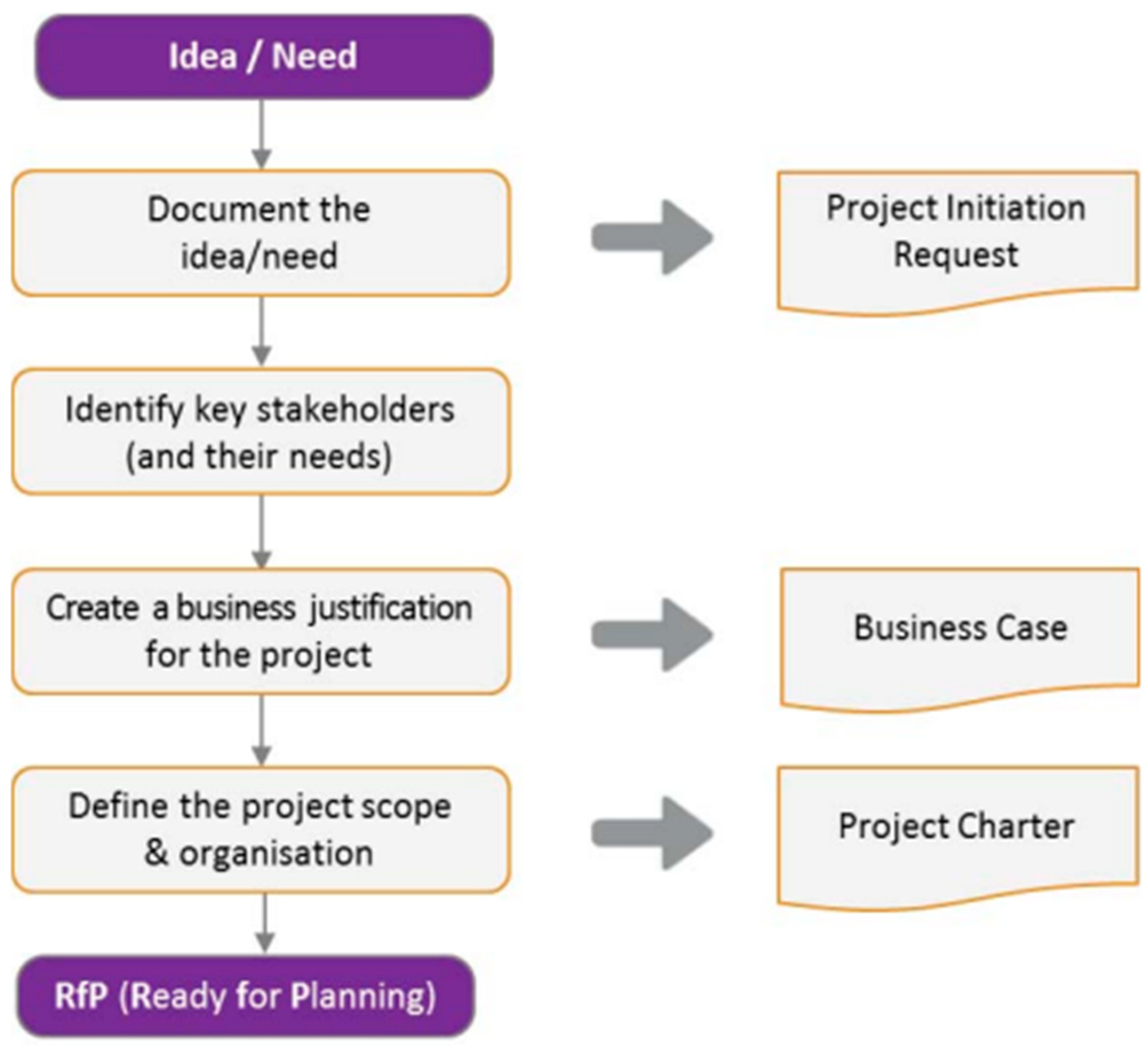

The Initiation Phase includes the definition of the intended results, the elaboration of the Business Case and the definition of the project scope. This phase starts with the Project Initiation Request, where an idea or need is identified. This is followed by the identification of stakeholders and their needs. After that, the project is defined in more detail and the economic justification for the project occurs, giving rise to the Business Case. Finally, the scope and organization of the project are defined and the Project Charter is created (includes more details about the scope, cost, time, quality, risk and constraints, general requirements, and establishes project milestones and deliverables). The flowchart of the Initiation Phase is shown in

Figure 9, where the activities and main deliverables are presented [

36].

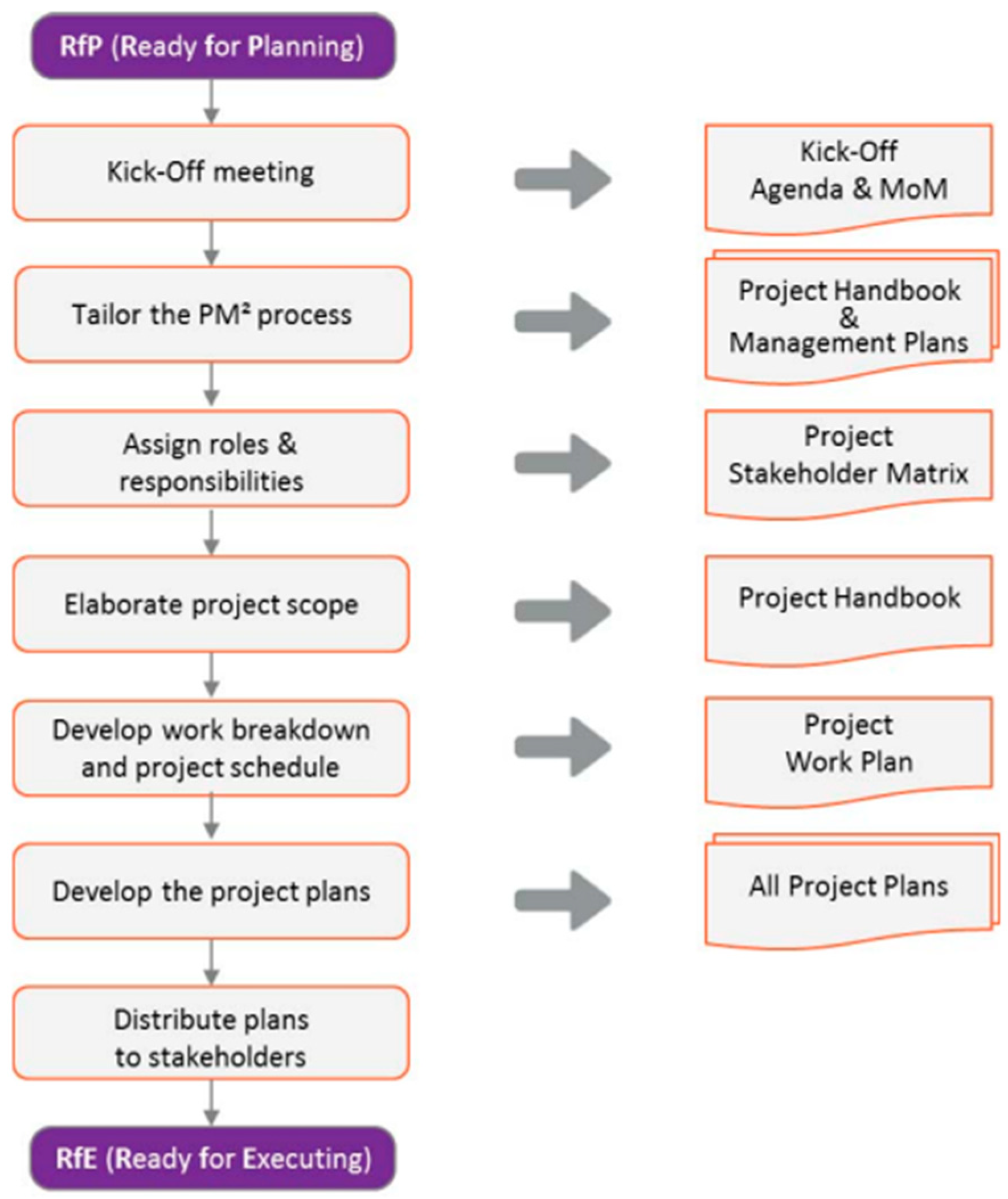

The Planning Phase starts with a Planning Kick-off Meeting. After that, the PM² process is adapted, originating the Project Handbook and Management Plans. Then the roles and responsibilities are assigned, developing the Project Stakeholder Matrix. This is followed by the Project Work Plan, which breaks down the work and defines the project schedule. In addition, there are other important plans, such as the Outsourcing Plan, the Deliverables Acceptance Plan, the Transition Plan and the Business Implementation Plan. After the approval by the Project Steering Committee, the Execution Phase follows. The flowchart of the Planning Phase is shown in

Figure 10, where the activities and main deliverables are presented [

36].

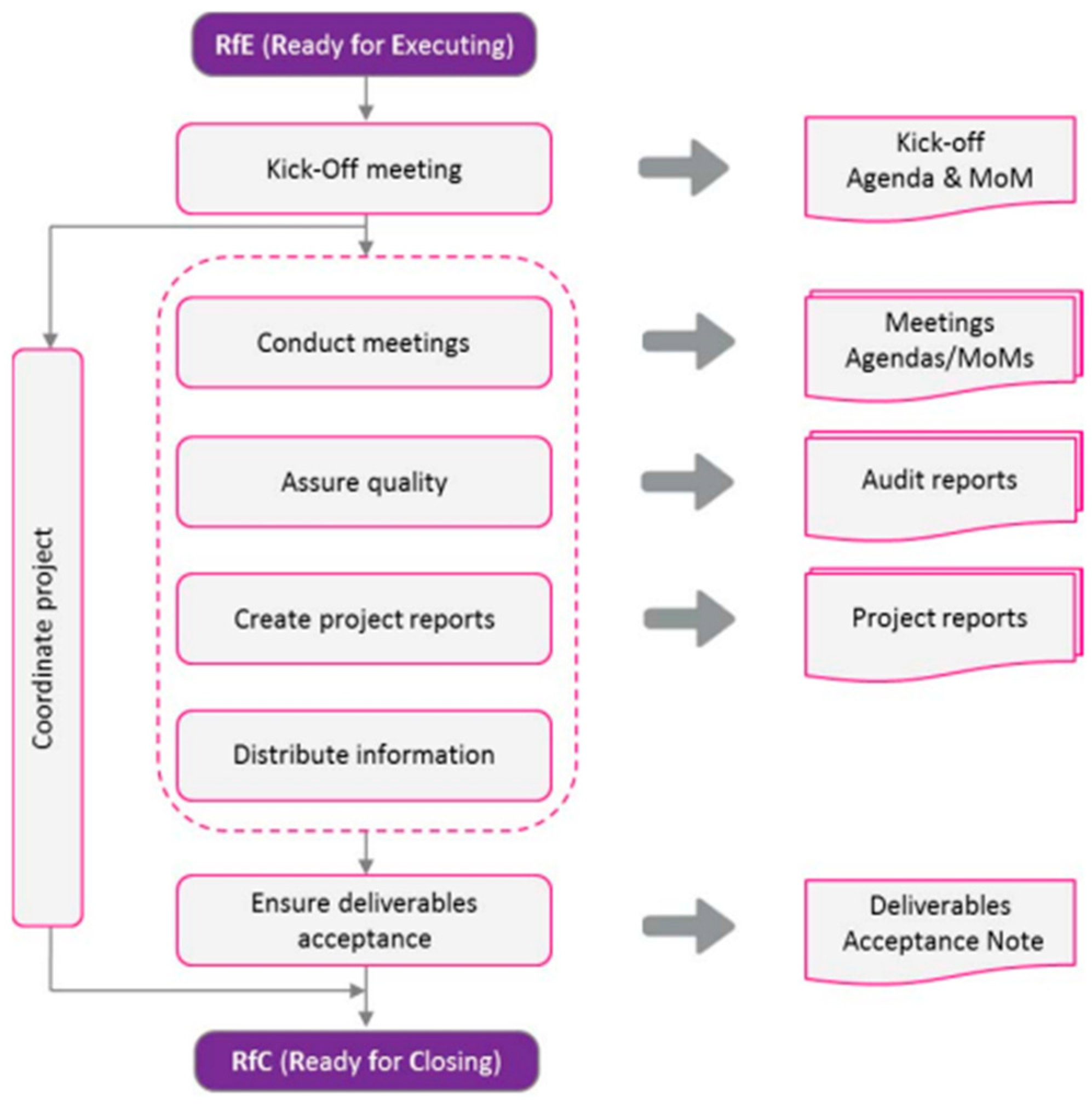

The Executing Phase starts with an Execution Kick-Off Meeting. The Project Coordination starts simultaneously with the beginning of the project and ends with its completion. To certify that the project work follows the best practices and standards there is the Quality Assurance activity, defined in the Quality Management Plan (allowing to certify that the project will have the intended scope and quality requirements and that it will be considering the project constraints). In this phase, the Project Reports are elaborated, allowing to document the evolution of the project to keep the relevant stakeholders informed. After the Project Owner accepts the project deliverables and the Project Steering Committee authorizes them, the Project Manager can move on to the Closing Phase. A summary of the Executing Phase is shown in

Figure 11, where the activities and main deliverables are presented [

36].

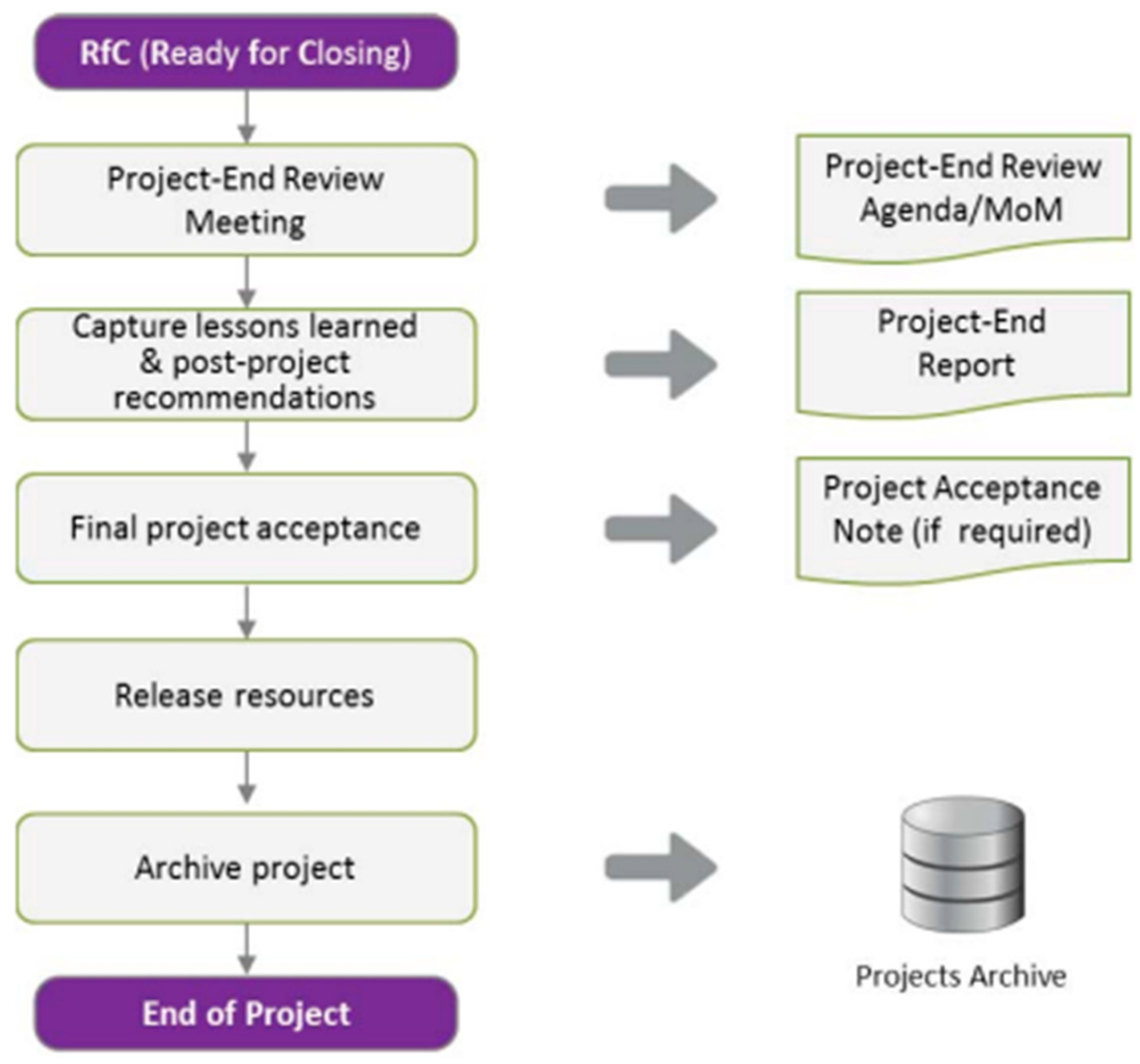

The Closing Phase involves finishing all activities, drawing lessons learned and recommendations, and closing and archiving all documents relating to the project. This phase starts with a Project-End Review Meeting. All the experience taken from the project is summarized in the Project-End Report (where the lessons learned are found). Once all the activities of this phase have been completed and after the Project Owner's approval, the project is officially closed. The flowchart of the Closing Phase, with its activities and main outputs, as recommended by the PM² methodology, is shown in

Figure 12 [

36].

Monitor and Control is a set of activities, according to PM², that occurs throughout the project life cycle, although it has greater relevance in the Executing Phase. Monitoring and controlling encompasses the control of all work by the Project Manager, such as measuring progress, managing changes, risks and problems, identifying and applying corrective measures and monitoring activities [

36].

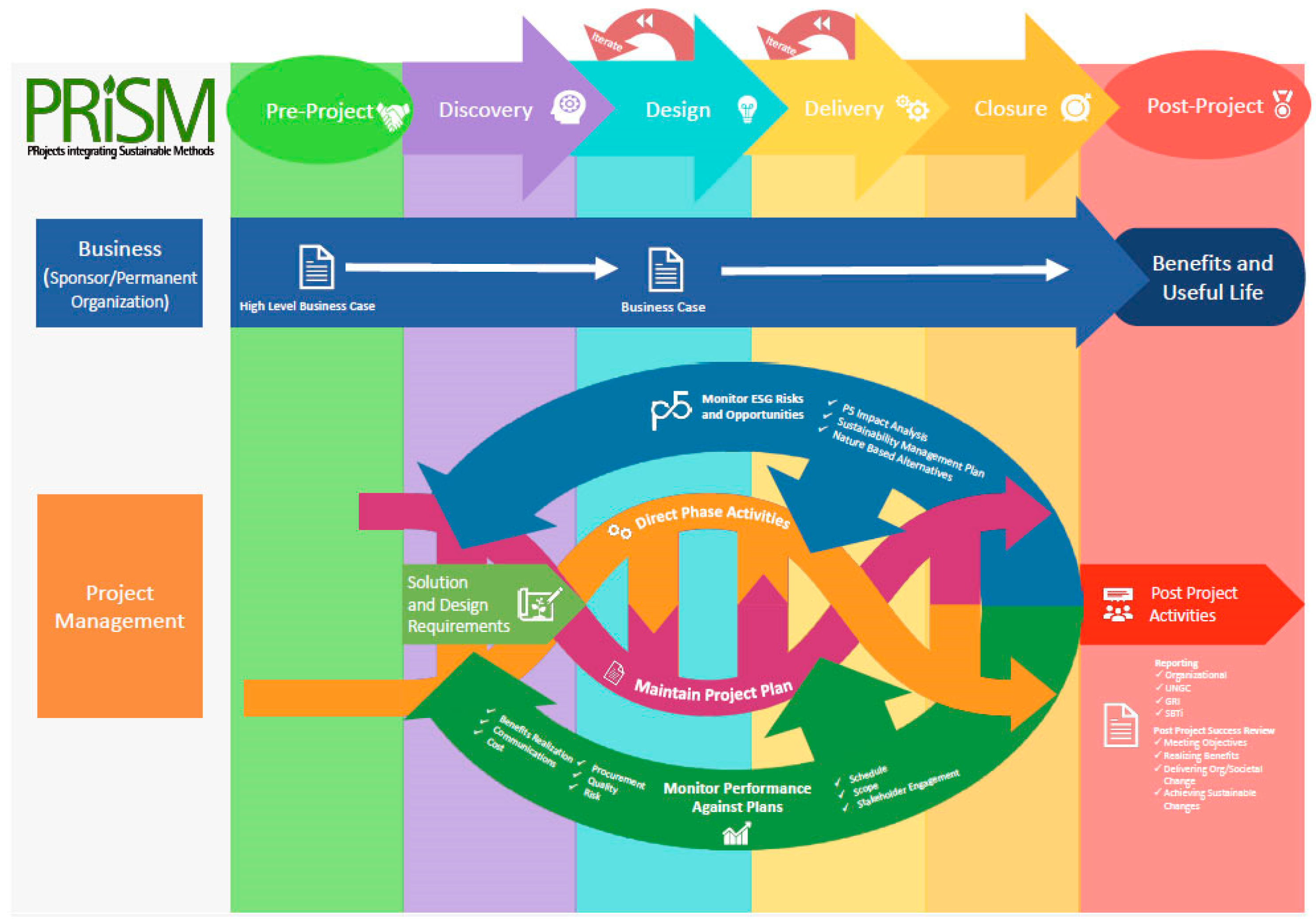

3.4.2. PRiSMTM

The PRiSM

TM methodology is based on the P5™ Standard for Sustainability in Project Management and aims to make the PM process more sustainable [

29]. For this reason, a short explanation of the P5™ standard is presented.

The P5™ standard is based on internationally recognized standards, among them the 2030 Agenda for SD, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact, ISO 20400:2017, ISO 37001:2016 and ISO 14001:2015. The main objective of P5™ involves the identification of possible negative and positive sustainability impacts, to be analyzed and presented to management for informed decision-making and effective resource allocation [

61].

The PRiSM

TM methodology has five phases: Pre-project Phase, Discovery Phase, Design Phase, Delivery Phase and Closure Phase. The Design and Delivery phases can be repeated several times.

Figure 13 shows the workflow of the PRiSM

TM methodology, encompassing the five phases, which are summarized below, according to the GPM

® reference guide [

29].

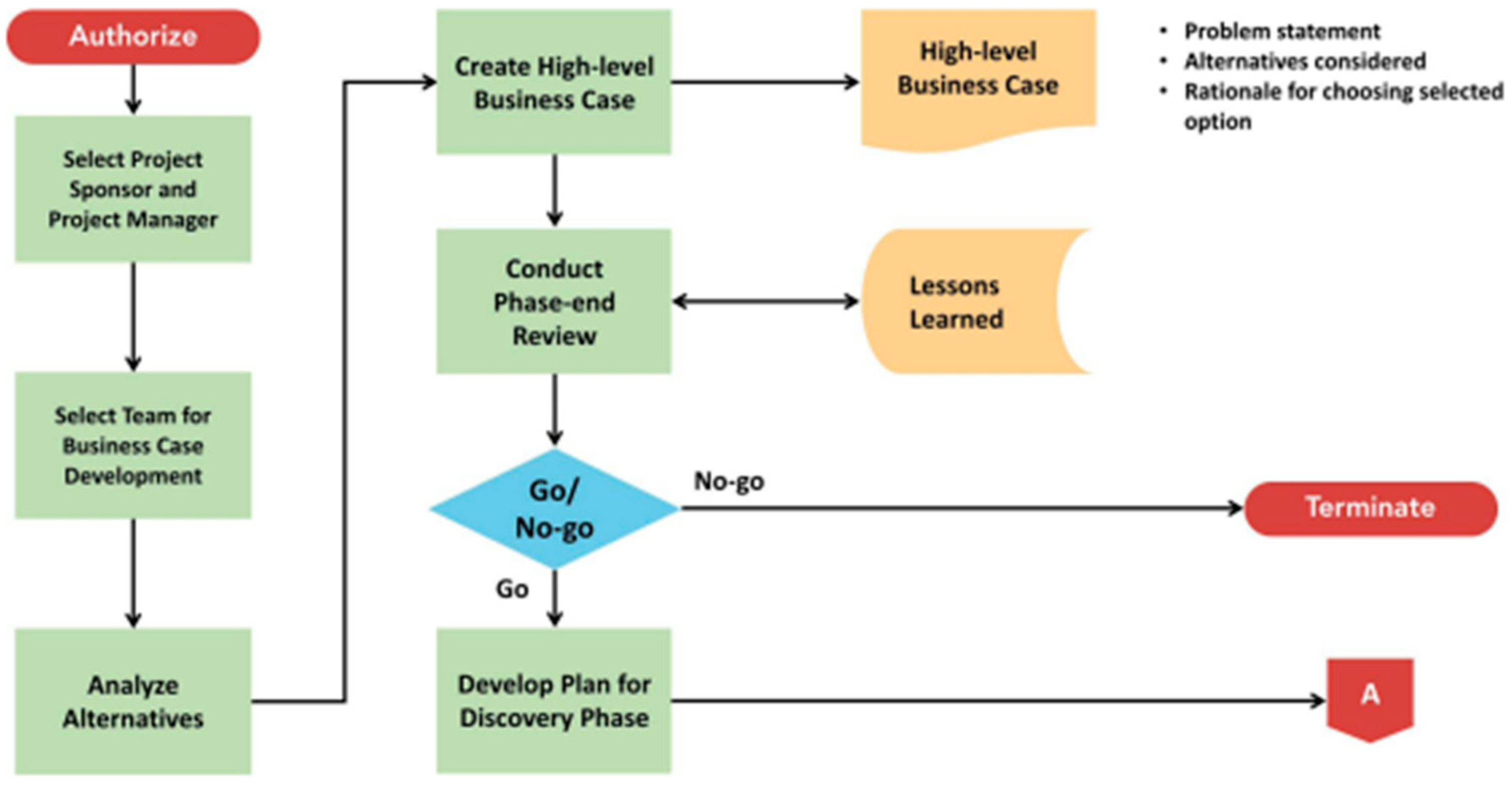

The Pre-Project Phase includes identifying the project objectives, determining the project sponsor and project manager partnership, beginning the development of the Business Case, and reviewing previous lessons learned. The Business Case may include, and in most cases does include, a high-level project plan (which has key deliverables, schedule targets, cost estimates, assumptions and possible primary constraints and risks). At the end of each phase, the Phase-End Review takes place, where the PM team must evaluate what has been accomplished to define whether the project should move on to the next phase. The summary of the Pre-Project Phase is shown in

Figure 14 [

29].

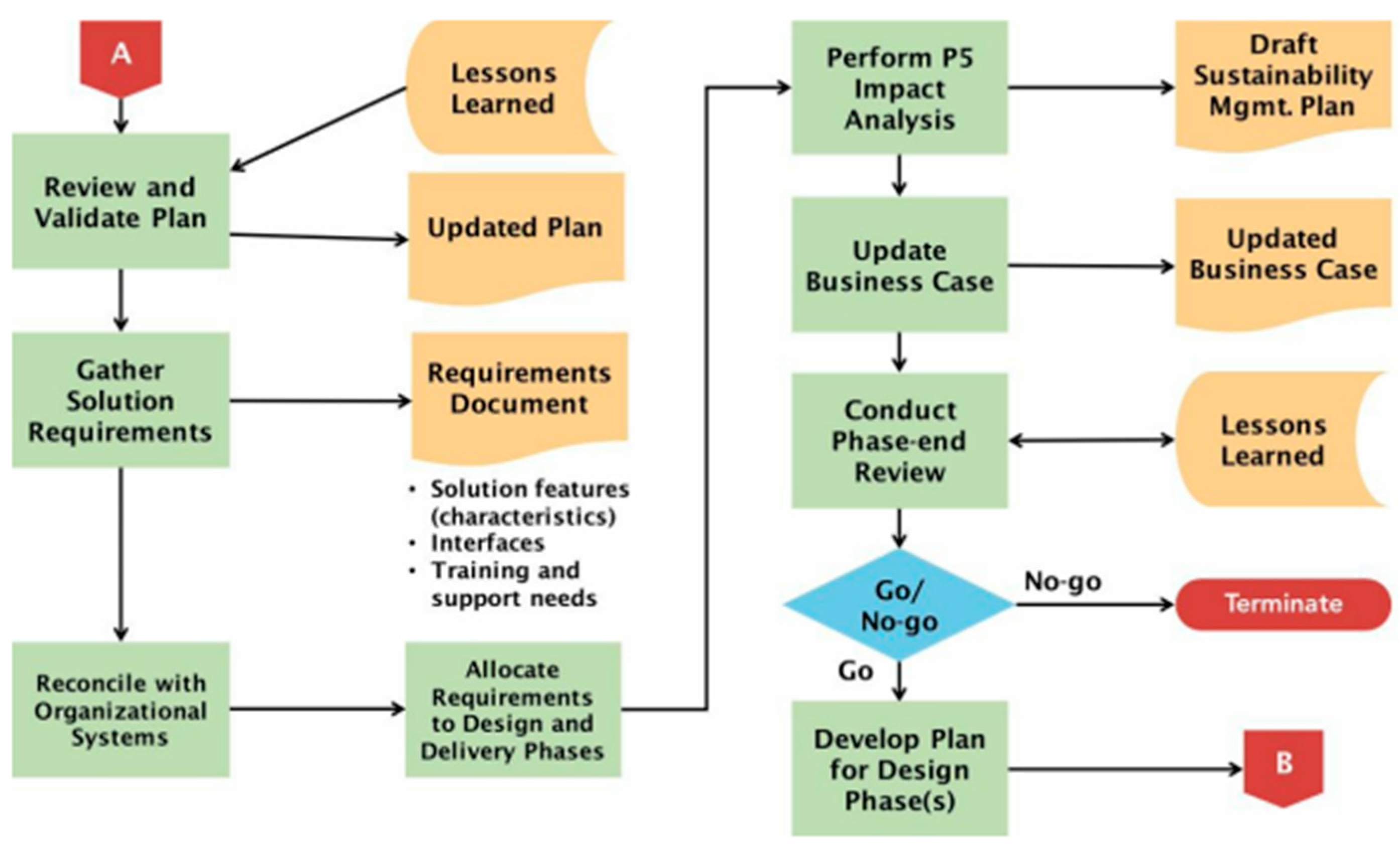

The Discovery Phase includes the definition of requirements, the alignment of the Business Case with the organization's systems, and the identification, analysis and conversion into opportunities of sustainability impacts.

This phase starts with the review of the plan developed in the Pre-design Phase by the PM team to ensure it remains relevant and useful. In this stage, the process of collecting the necessary information to complete the requirements documents (sustainability, user, functional, non-functional and implementation) takes place.

After, it is necessary to reconcile the project objectives and plans with the organization's systems. Furthermore, this phase encompasses the determination of the requirements that will be addressed in each phase of the project and in the delivery. Another step belonging to this phase involves the P5 Impact Analysis, which involves analyzing environmental, social and economic criteria, to achieve sustainable results. Also in this phase, it becomes important to check the validity of the Business Case. If necessary, it should be updated. Finally, the Phase-End Review takes place and the decision to move forward with the project to the next phase or to close it by the sponsor. The summary of the Discovery Phase is shown in

Figure 15 [

29].

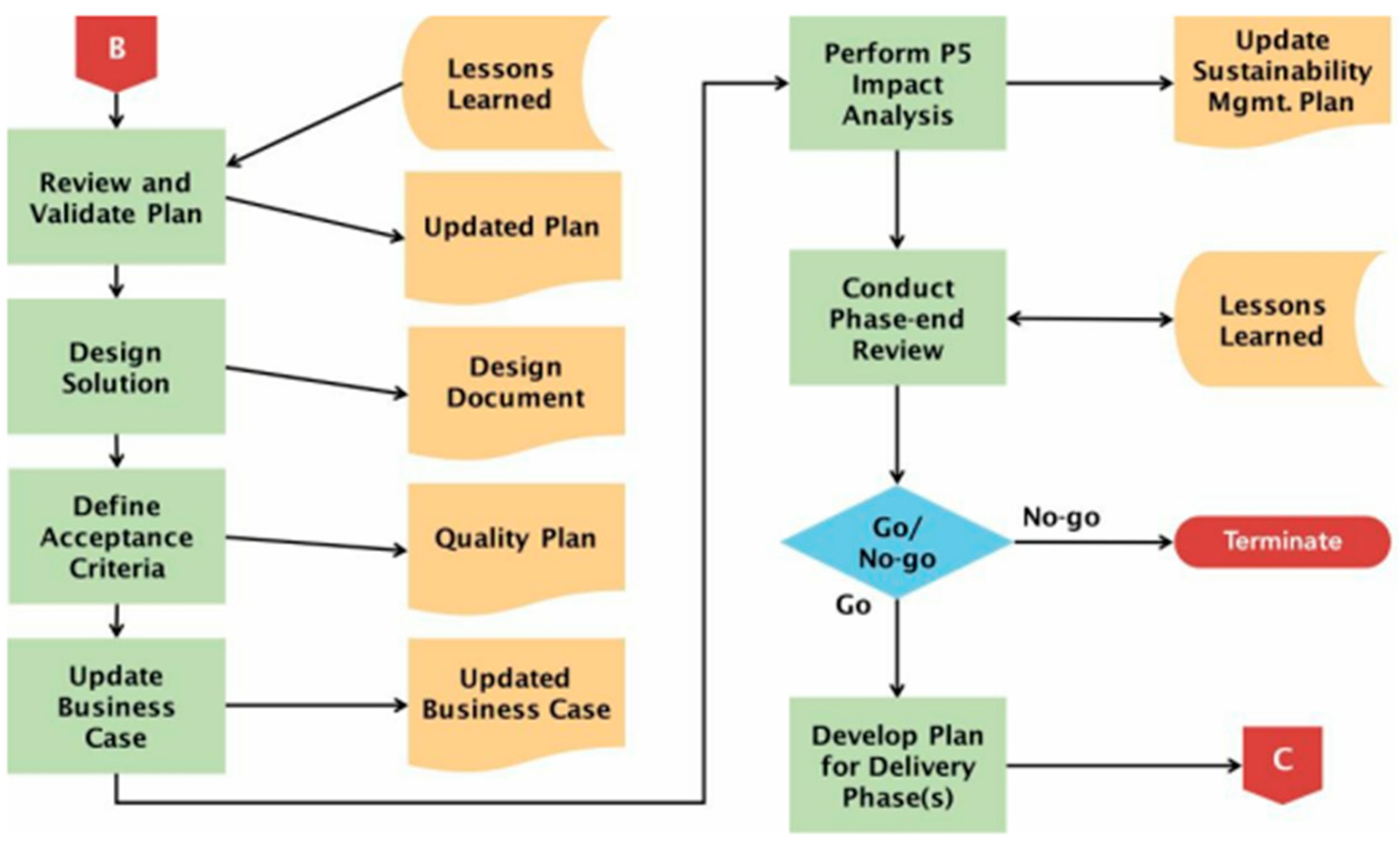

In the Design Phase, the solution is designed, a sustainability analysis is carried out and acceptance criteria are established. The Design Phase begins with the review and validation of the plan developed by the project team in the previous phase. Next, the projection of a product or service of the project takes place, to determine the needs related to resources, costs, schedule, risk, value, benefits and impacts. After that, the definition of acceptance criteria follows, where criteria to be met before the approval of the project deliveries by the sponsor are documented. At this stage, it is also important to update the Business Case, so that it remains valid. In addition, the execution of the P5 Impact Analysis takes place, where the design processes are analyzed concerning environmental, social and economic criteria, to ensure that the results are considered sustainable. As in the previous phases, at the end of the Design Phase, the Phase-End Review takes place. The summary of the Design Phase is shown in

Figure 16 [

29].

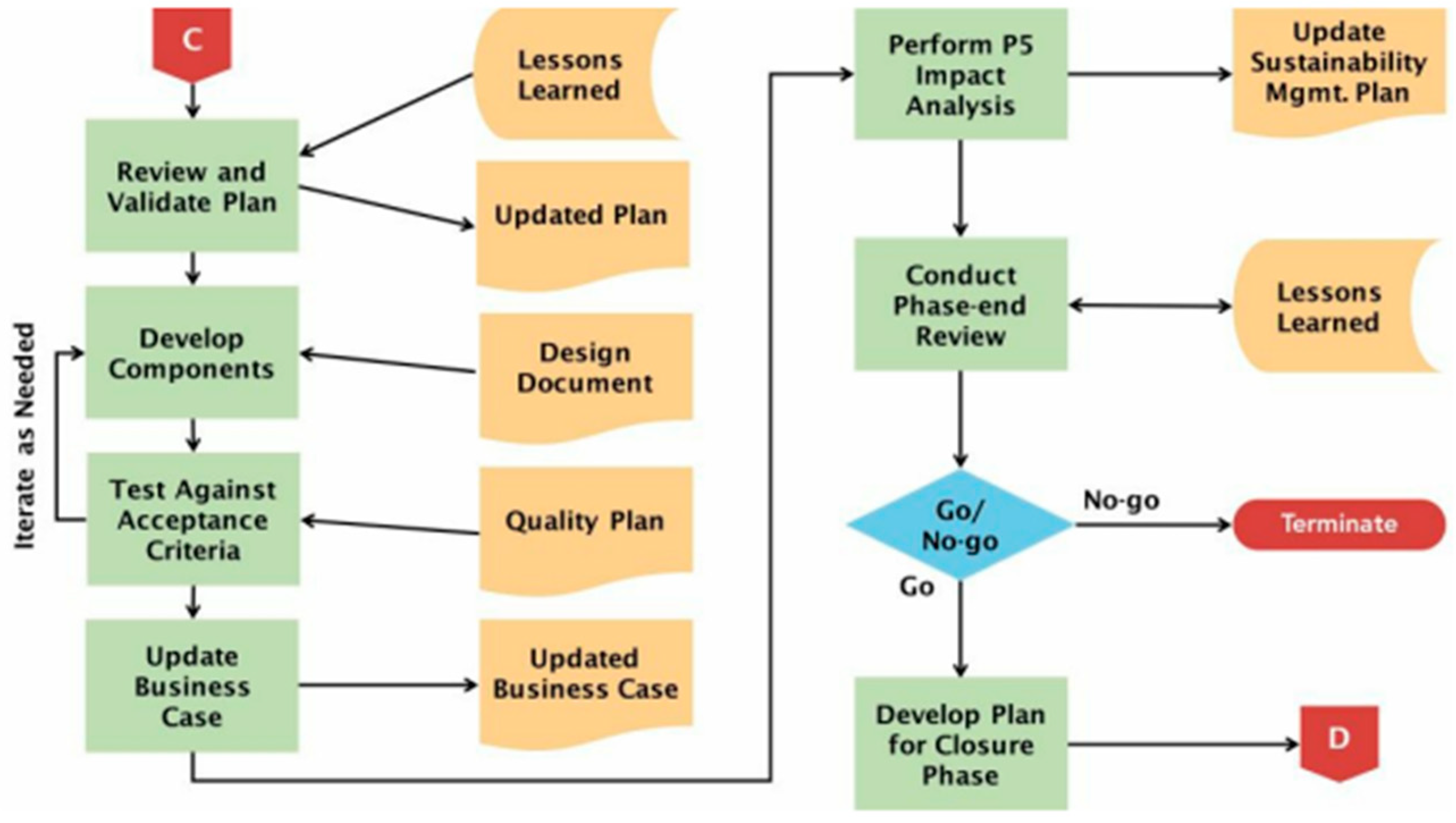

The Delivery Phase includes the production of the required deliverables by the project team, to achieve the expected objectives and benefits. This phase also starts with the review and validation of the plan developed at the end of the previous phase. From that moment on, components are developed, and the project deliverables are made or purchased. In addition, the testing of the acceptance criteria takes place, so that the sponsor can decide on the project deliveries and the update of the Business Case. In this phase, a P5 Impact Analysis is also carried out, where the delivery processes are analyzed concerning environmental, social and economic criteria. At the end of this phase, the Phase-End Review also takes place. The summary of the Pre-Project Phase is shown in

Figure 17 [

29].

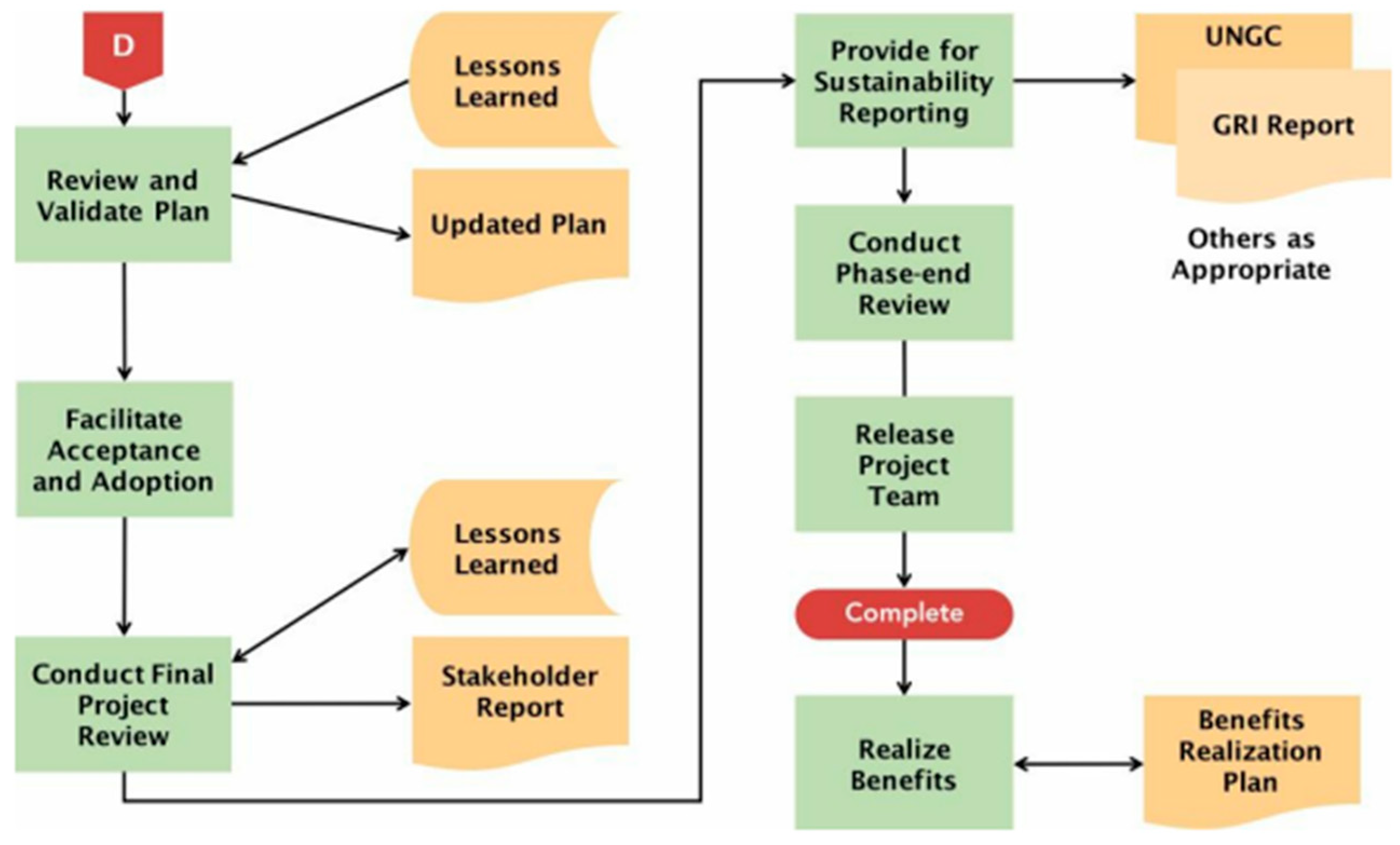

In the Closure Phase, the adoption of the project deliverables by the project team is facilitated and the project is administratively closed. This phase starts with the review and validation of the plan developed at the end of the previous phase. After that, acceptance and adoption facilitation takes place, where deliverables to relevant parties and their adoption are coordinated, which may include support to ongoing operations and maintenance, organizational changes and end-of-life planning. In addition, a final project review takes place, where successful or unsuccessful elements of the project are reviewed by the project team. Also, in this phase, information for the Sustainability Report is provided, through the production of an organizational materiality report of the Sustainability Management Plan. Finally, the formal release of the project team and the realization of business benefits as a result of the project takes place. The summary of the Closure Phase is shown in

Figure 18 [

29].

4. Results

This chapter contains the results obtained from the analysis of the presence of the term "sustainability" in PM guides and scientific publications and the analysis of PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies based on guides, scientific publications and interviews.

4.1. The presence of the term "sustainability"

This section presents the results obtained from the analysis of the presence of sustainability in some PM guides and scientific publications obtained through the SCOPUS database.

4.1.1. Sustainability in project management guides

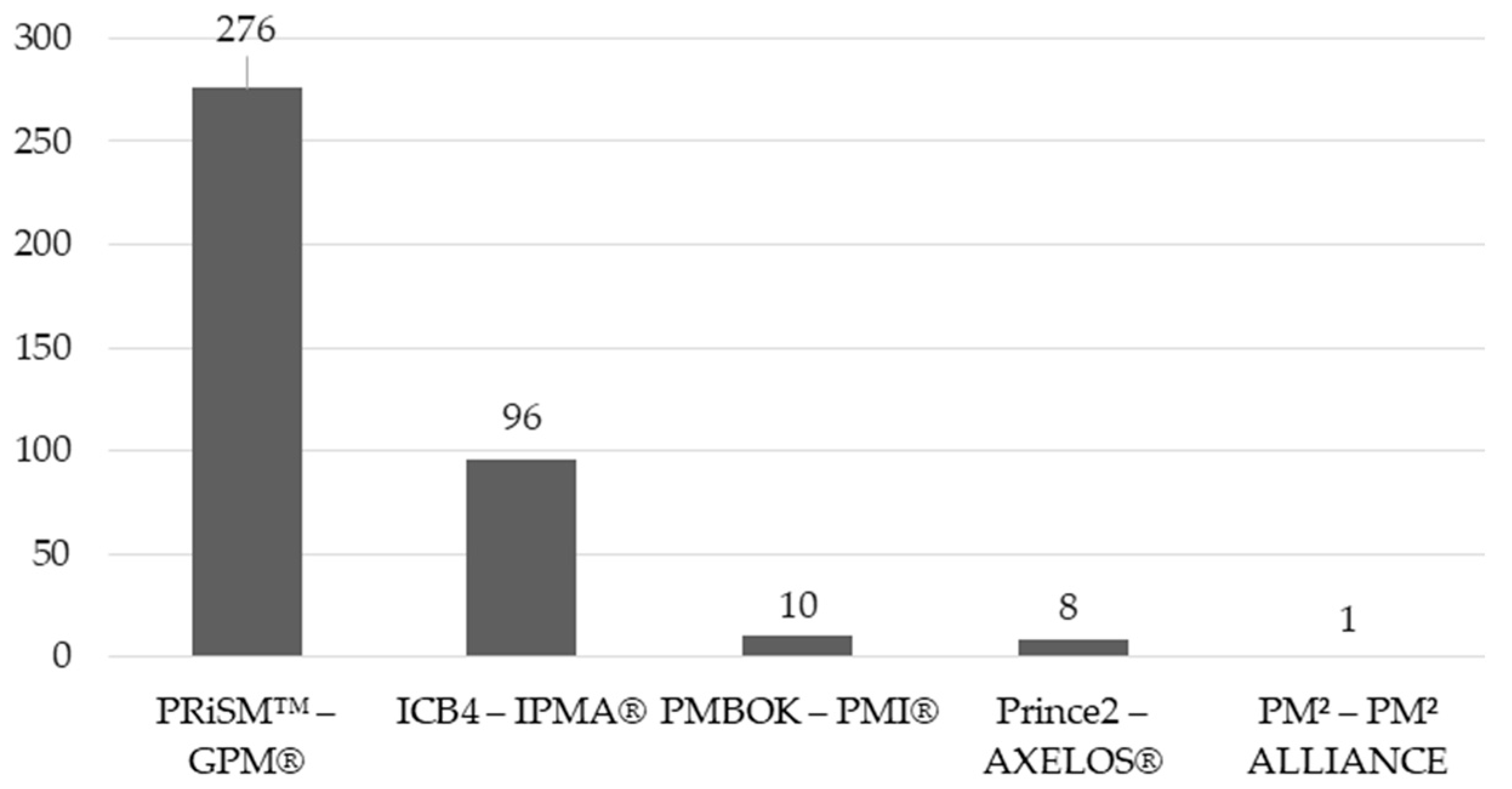

From the previously mentioned guides, section 2.2.2., it was removed the number of times the words mentioned previously, in the same section, appeared, originating in

Figure 19.

Through the analysis of this figure, it can be concluded that the standard that most mention sustainability is the GPM® standard, with a total of 276 mentions, which would already be expected since its vision focuses on the "green" PM. The PM² methodology was, among the standards analyzed, the one which mentioned sustainability the least, with only one mention. ICB4 mentions this topic 96 times, PMBOK® 10 times and PRINCE2® eight times.

4.1.2. Sustainability in project management in scientific publications

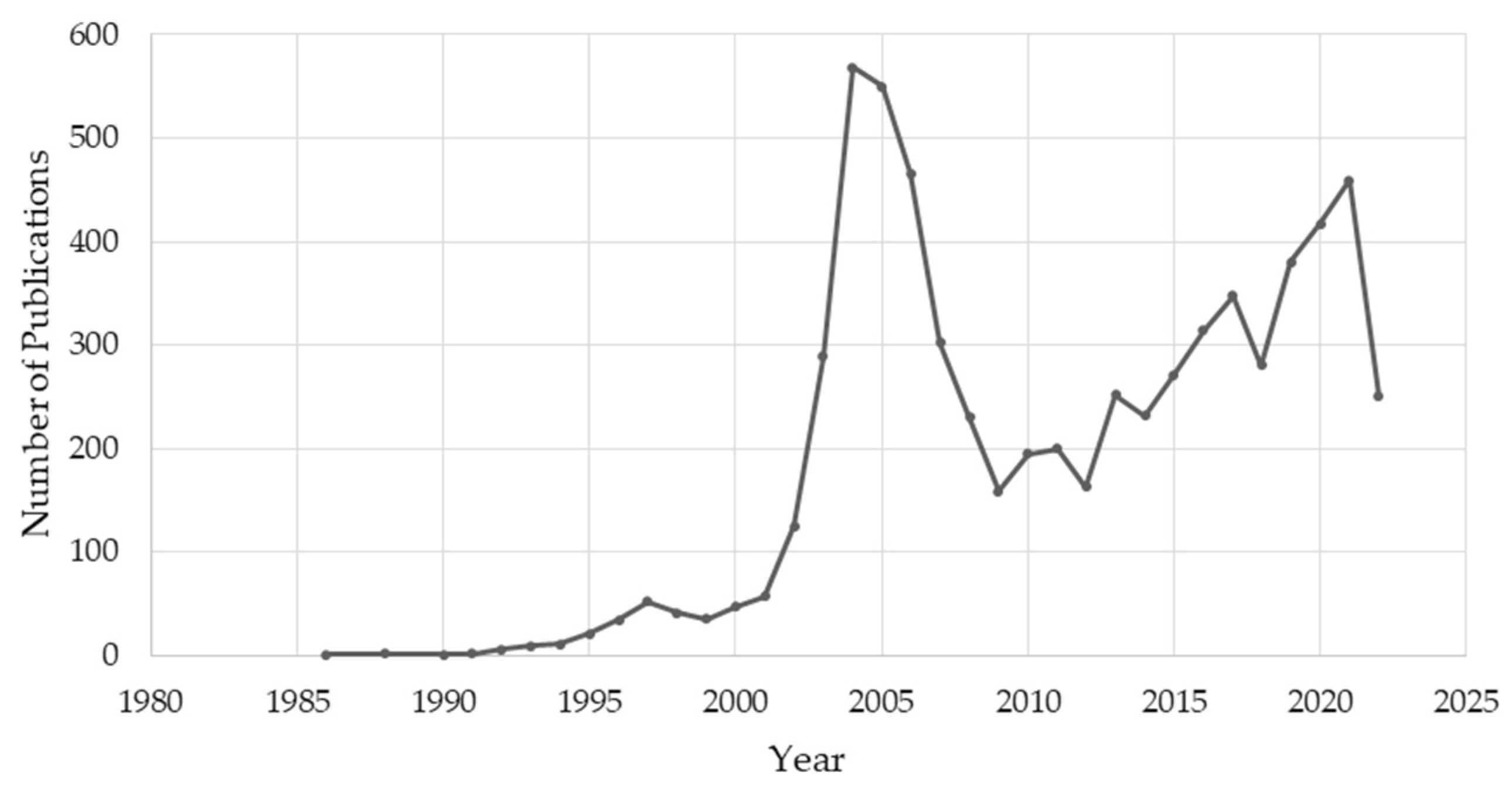

To understand to what extent sustainability in PM is disseminated throughout the world and over the years, the 6769 documents, returned by the SCOPUS database mentioned earlier in section 2.2.2., were analyzed. The results are present in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21.

The number of papers found is considered relatively small, a fact also noted and justified by Stanitsas et al. (2021) [

12], and is due, according to the same author, to the fact that the area under analysis is relatively new and under development.

The separation of the articles by continents from which they originated is shown in

Figure 20.

Through the analysis of

Figure 20, it can be seen that North America, Europe, Asia and Australia have more publications on sustainability in PM than Africa and South America.

The United States, China and the United Kingdom are the three countries with more documents on this subject. It should be noted that in Portugal the number of documents on these themes seems to be relatively small.

Next, the temporal distribution of the documents was carried out to see the trend over the years, which resulted in the graph of

Figure 21.

The junction of the two themes appears in the 80s, more precisely in the year 1986, with only one publication;

Between 1985 and 1994, the number of published articles can be considered insignificant;

An abrupt growth in the number of publications between the years 1999 and 2004;

2004 and 2005 were the years with more papers that include the sustainability theme in PM;

A decreasing trend in the thematic from 2004 to 2009;

A gradual rise between 2009 and 2021, with some occasional exceptions.

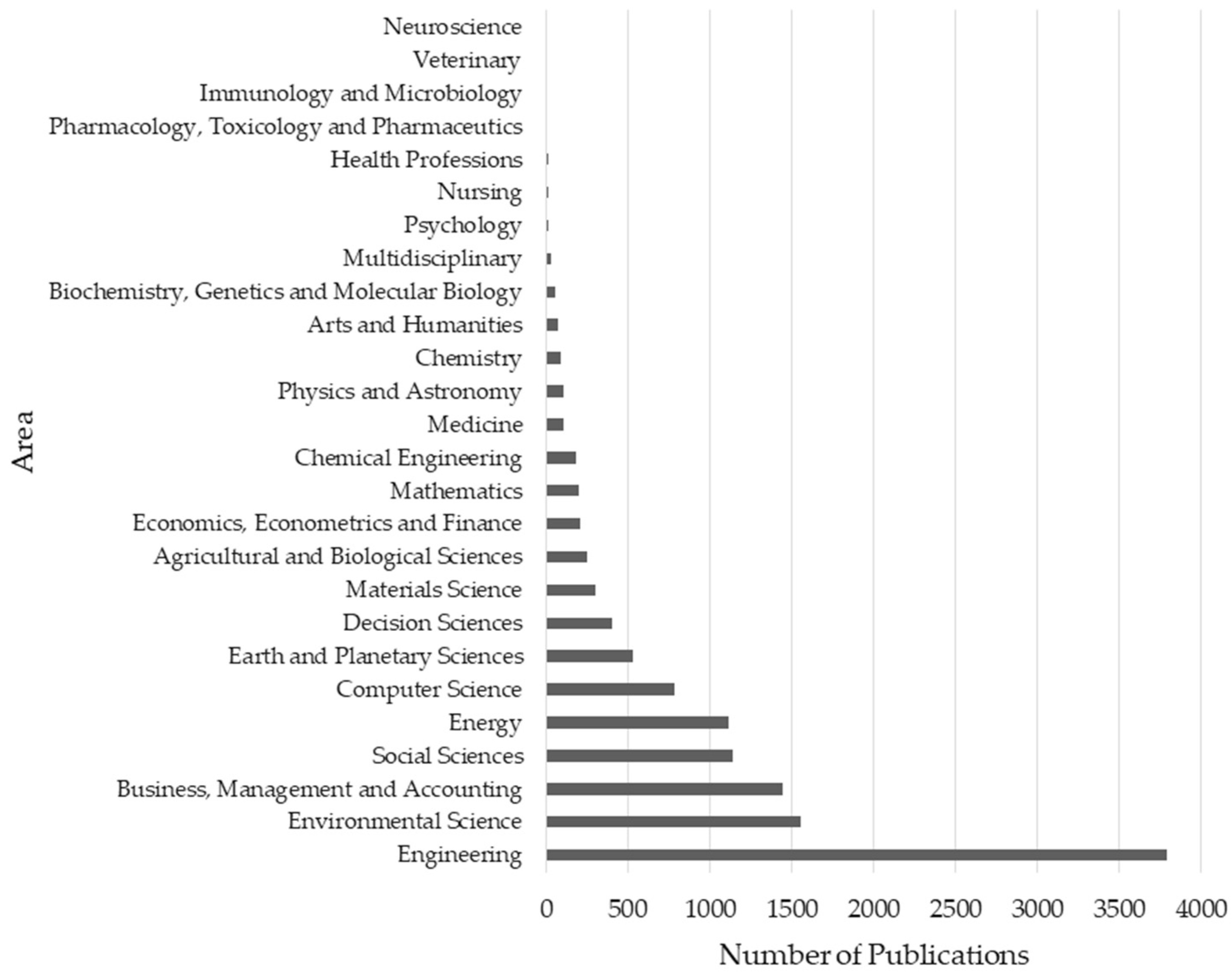

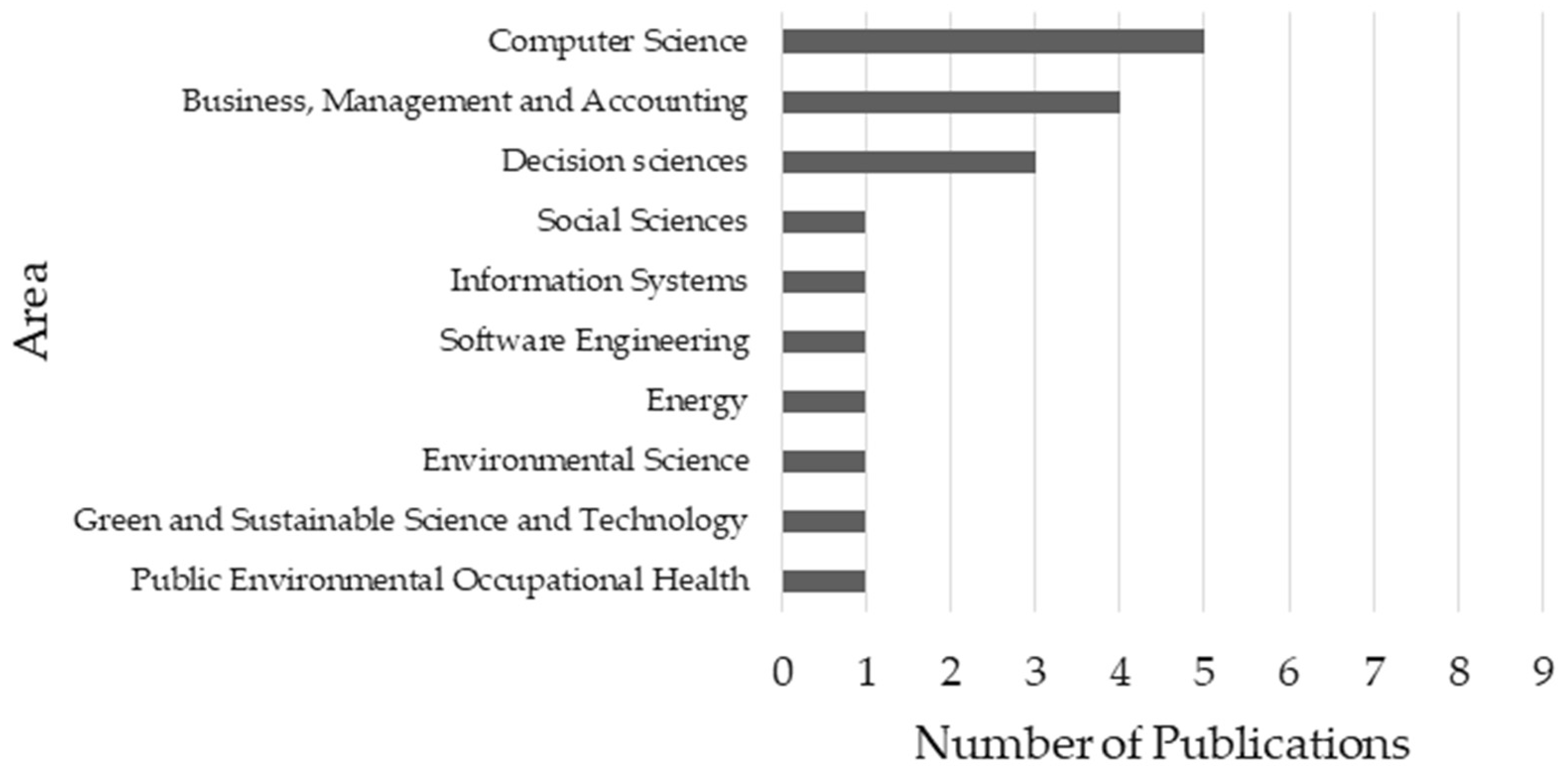

The chart present in

Figure 22 was elaborated to depict the most "active" areas in terms of scientific writing on the topic of sustainability in the PM.

From the analysis of the graph in

Figure 22 it can be concluded that the three areas that produce the majority of the documents with the theme of sustainability in the PM are: i) engineering; ii) environmental science; and iii) business, management and accounting. The last three positions are: i) immunology and microbiology; ii) veterinary medicine; and iii) neuroscience.

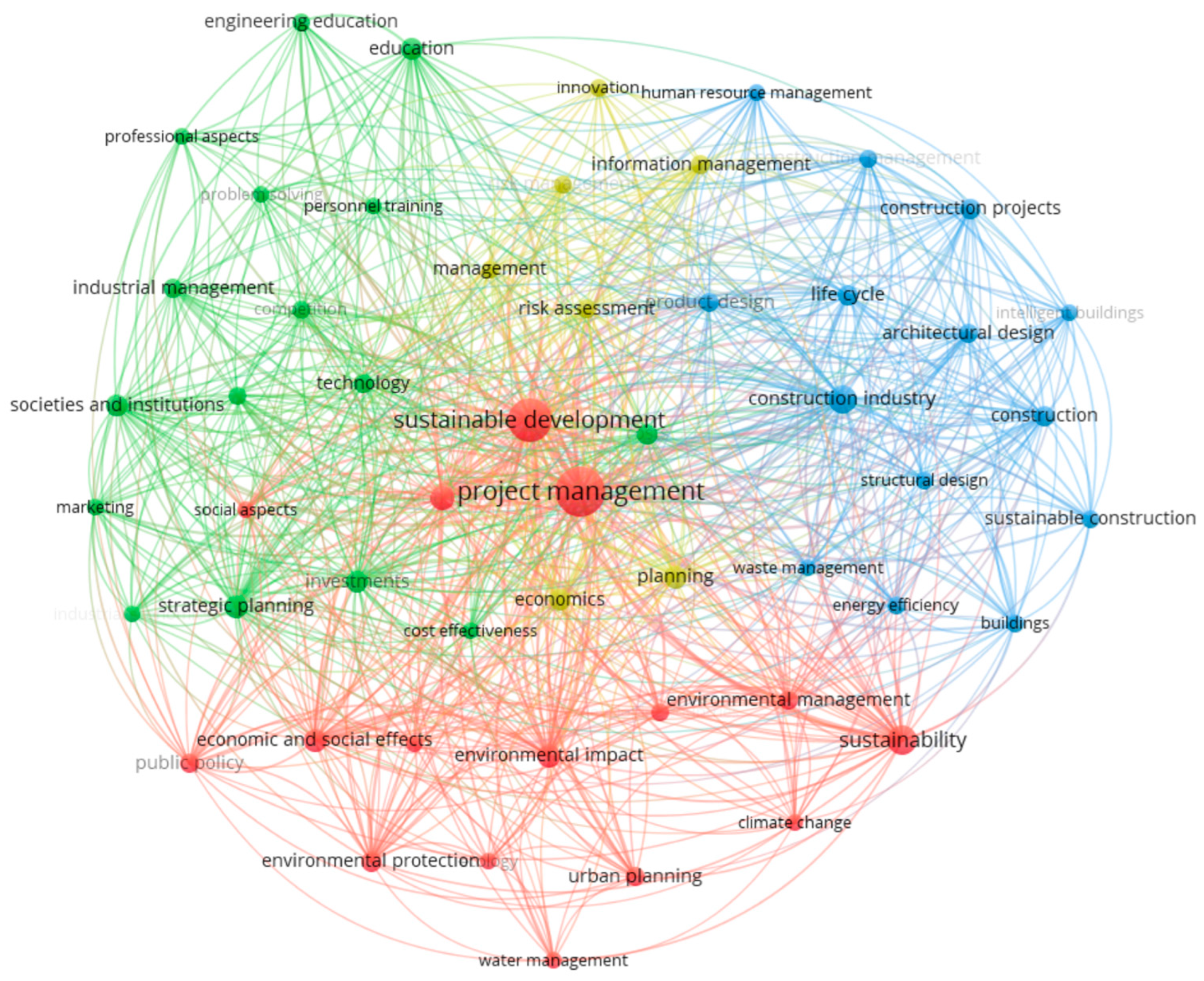

After the analysis presented above, an analysis was performed, in the VOSVIEWER software, to make the separation by word clusters. The result is shown in

Figure 23.

On the one hand, the ten most mentioned topics are PM, SD, construction industry, sustainability, decision-making, environmental impact, economic and social effects, strategic planning, planning, societies and institutions.

On the other hand, the ten least mentioned topics are water resources management, climate change, ecology, problem-solving, employee training, cost efficiency, waste management, innovation, marketing, and social aspects. It should be noted that the construction industry cluster is one of the clusters that, judging by the number of publications, is giving more importance to the topic of sustainability in PM.

4.2. Analysis of PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies

This subsection presents the results of the analysis carried out on the two methodologies under study - PM² and PRiSMTM - in order to verify where the differences and similarities lie, both in terms of the approaches and the tools/techniques proposed by the methodologies. This analysis is divided into three parts, analysis based on their guides, scientific publications and interviews.

4.2.1. Analysis based on guides

One of the major differences between these two methodologies can be found in their main objective:

Next, the similarities and differences between the definitions of "project" and "PM" of the two methodologies were analyzed. Results are shown in

Table 4.

By analyzing

Table 4 it can be observed that the project definition presented in PRiSM

TM and PM² appear to be very similar. Common points are the finite period of time, with a defined beginning and end and the intention to create a unique result, which has not been created before. However, while the PRiSM

TM methodology defines a project as an investment, PM² defines it as an organizational structure. PM definitions have the same objective: to coordinate projects and achieve goals effectively and efficiently.

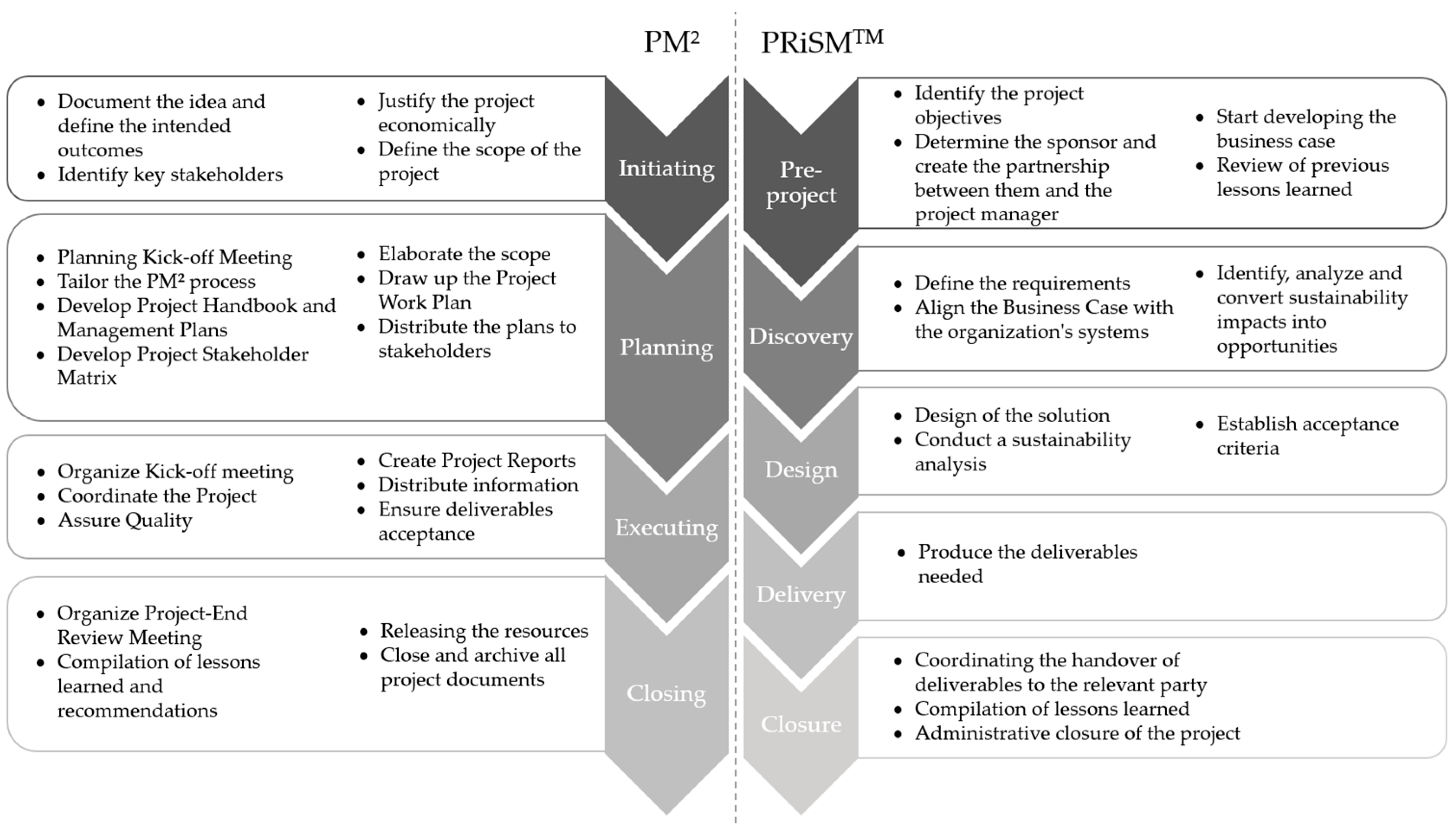

To simplify the comparison of the life cycle of the two methodologies, a summary is presented in

Figure 24.

Another difference that can be highlighted relates to the number and name of the phases of the project life cycle. The "PM² project" is divided into four phases: i) Initiating Phase; ii) Planning Phase; iii) Executing Phase; and iv) Closing Phase. The "PRiSMTM project" is divided into five phases: i) Pre-project Phase; ii) Discovery Phase; iii) Design Phase; iv) Delivery Phase; and v) Closure Phase. The only phase with a similar name is the Closing/Closure Phase.

Through the analysis of

Figure 24, it can be seen that the PRiSM

TM methodology identifies and analyses sustainability impacts, converts them into opportunities in the Discovery Phase and refines a sustainability analysis in the Design Phase. So there is a great focus on the question of sustainability during the design of the project. The PM² methodology doesn’t mention this issue - sustainability - directly in any of its phases. As mentioned earlier (

Figure 19), the word sustainability is only mentioned once in the entire guide. The mention of the word "sustainability" appears in the appendices, in the PM² programme management in PM² extensions, in the Closing Phase: "The Lessons Learned and Post-Programme Recommendations are formulated in the Programme-End Report, facilitating the sustainability of the realised benefits after the programme has ended" [

36] (p. 108). Thus, it can be verified that sustainability appears, in a direct way, only associated with the future benefits associated with the project and is never mentioned during the project Executing Phase.

Next, an analysis and comparison of the deliverables of the two methodologies was conducted (see

Table 5).

By analyzing the artefacts, in

Table 5, it can be observed that in the PM² methodology, there is no artefact related to sustainability. In the PRiSM

TM methodology, there is the P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan as an artefact directly linked to sustainability. In common, the methodologies have the Business Case and the Requirements Document. Most of the remaining deliverables seem similar, in terms of scope, but with slightly different names which may be an obstacle to their simultaneous use in the same organization. Therefore, it can be confirmed what is referred to in the methodology itself about the P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan are the main differentiators from other approaches [

29].

The PRiSM

TM methodology establishes success criteria (Structured Success Criteria, Product Success Criteria, Project Management Success Criteria and Criteria for Good Success Criteria) concerning the product and the PM in the Business Case. In addition, in monitoring and control, the success criteria are also referred to, since the objective of controlling is presented as the best way to achieve the project success criteria. It is still proposed the application of corrective actions to improve the opportunity to achieve the success criteria and it is up to the sponsor to verify the viability of a project considering the success criteria in the various phases [

29]. The PM² methodology establishes success criteria with which the project will be evaluated, in the Project Initiation Request [

36]. Therefore, it can be stated that the success criteria are more detailed in the PRiSM

TM methodology, which in itself is a guarantee of a better understanding by all stakeholders.

4.2.2. Analysis based on scientific publications

The 20 publications, referred to previously, were analyzed according to their areas of study, years, geographical dispersion and features of the methodologies.

Of the eight publications referring to PM², five are Conference Papers and three are Journal Papers. Of the 12 publications referring to PRiSMTM, five are Conference Papers and seven are Journal Papers. Thus, it can be seen that the publications relating to the PM² methodology are mostly Conference Papers, while those of the PRiSMTM methodology are Journal Papers.

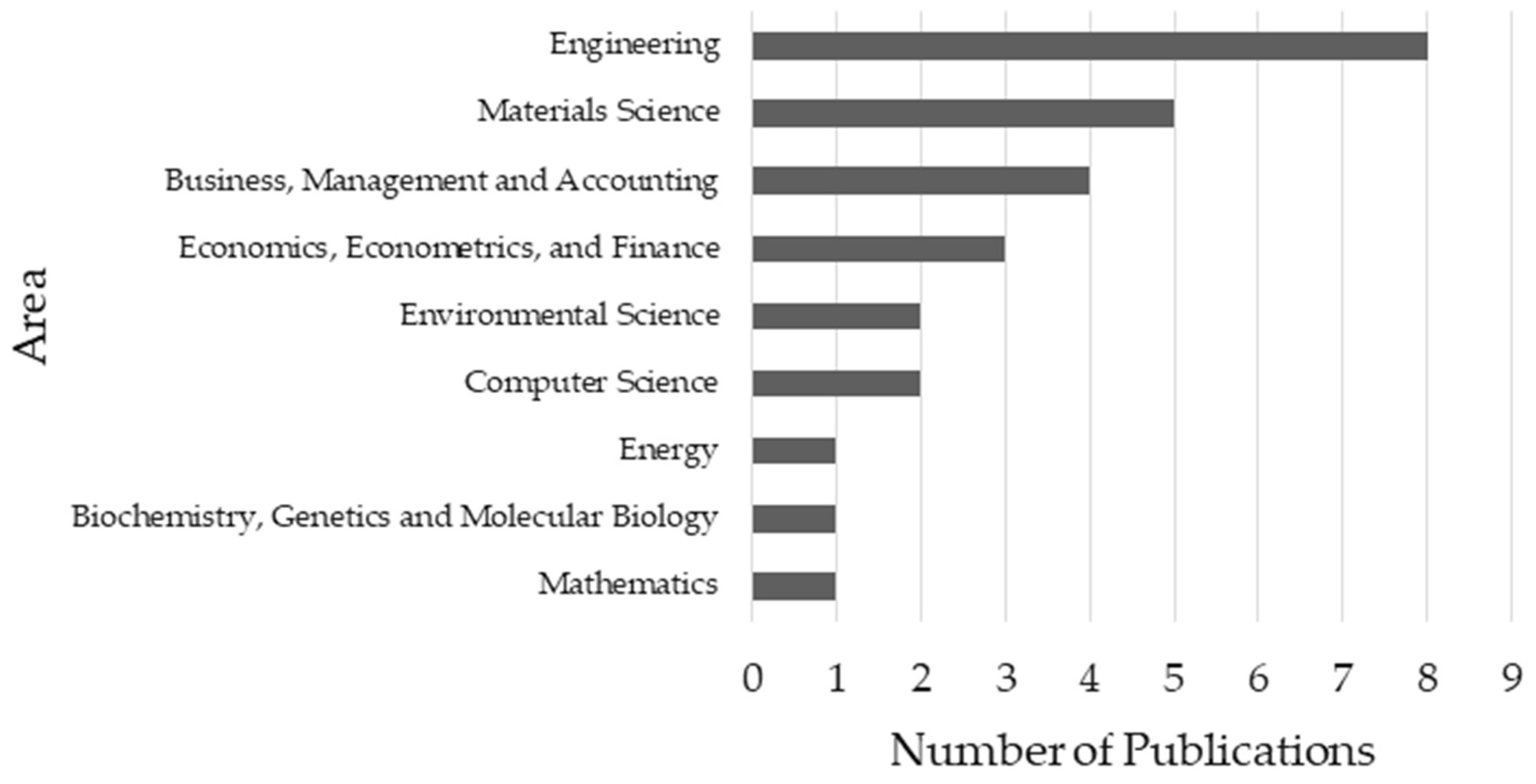

Initially, the publications were analyzed according to their areas of study, which resulted in the histograms of

Figure 25 and

Figure 26.

Through the analysis of the histograms, it is clear that the publications of the PM² methodology are more concentrated in the areas of computer science and business, management and accounting. In the case of the PRiSMTM methodology, the publications are more concentrated in the areas of engineering and materials science, different from the PM² methodology.

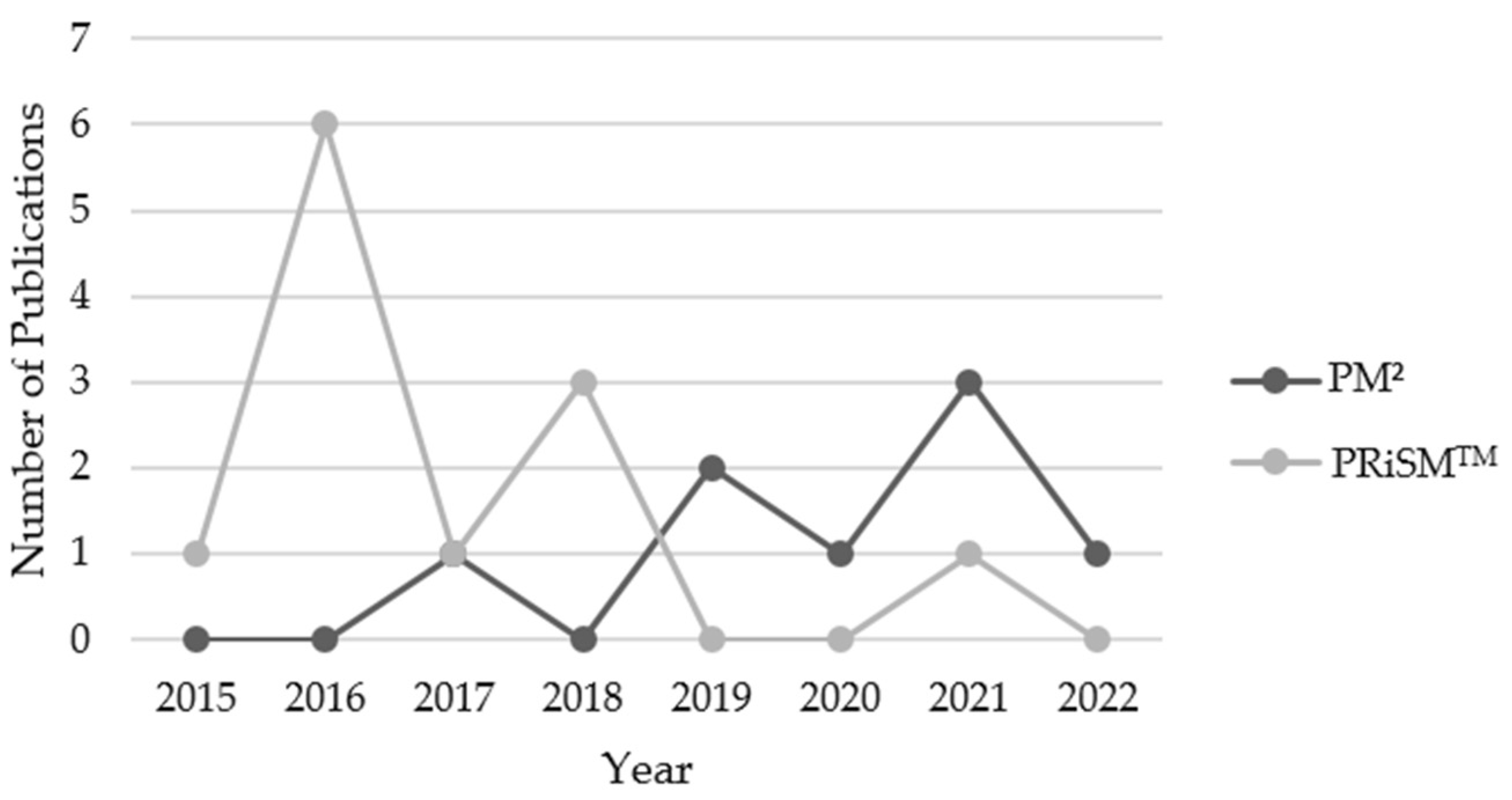

The number of articles published per year regarding the two methodologies is shown in

Figure 27.

Through the analysis of the graph (

Figure 27), there is an increasing trend in the number of publications that address the PM² methodology. Those that address the PRiSM

TM methodology, contrary to expectations, show a decreasing trend. From the analysis of the graph, it is also possible to conclude that the two methodologies - PM² and PRiSM

TM - went in a counter-cycle: while one gained traction the other decreased in number of publications between 2015 and 2019. Only between the years 2020 and 2022, the methodologies are aligned in terms of publication number trends - when one grows the other also grows and when one declines the other also declines although with small differences in pace.

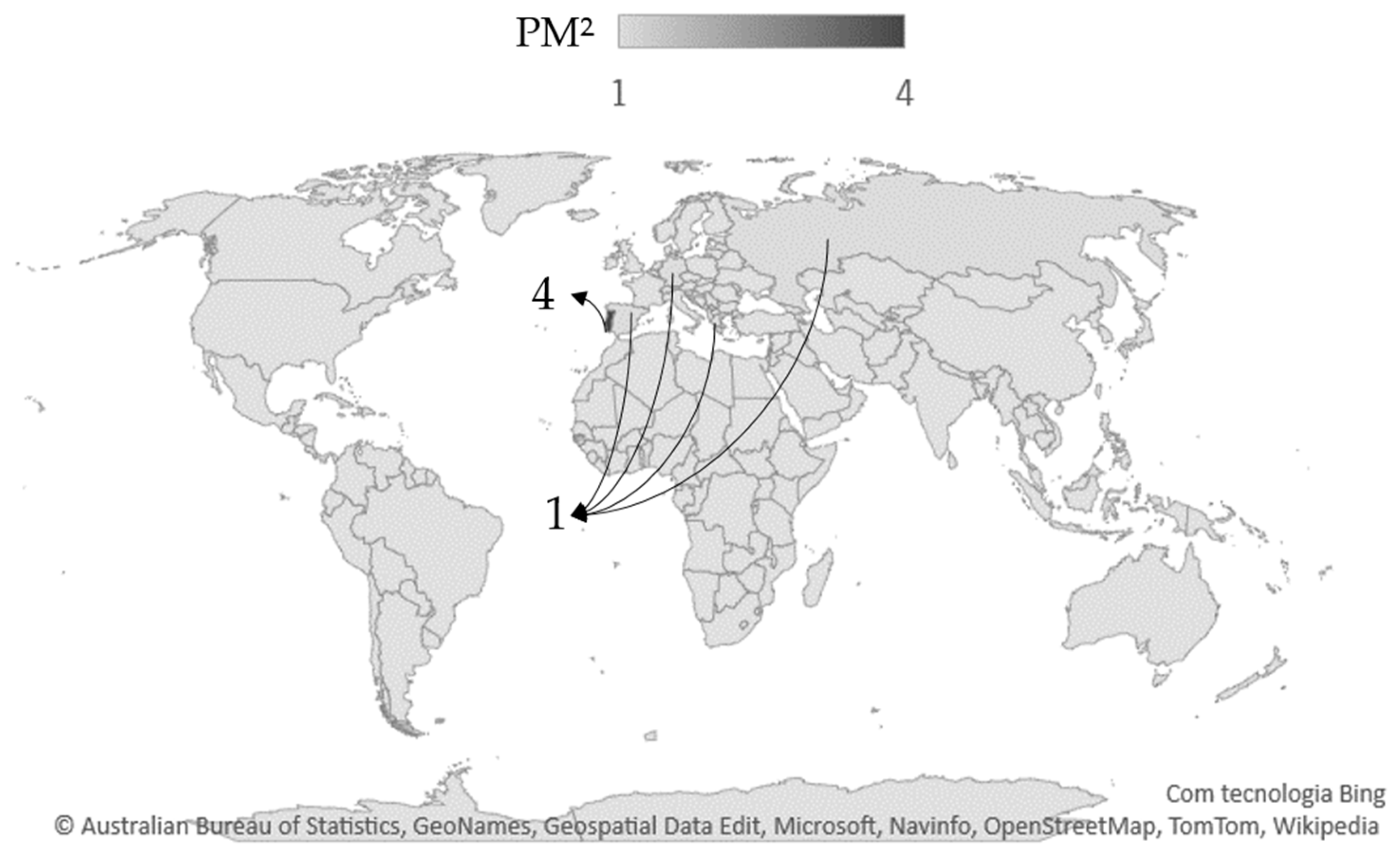

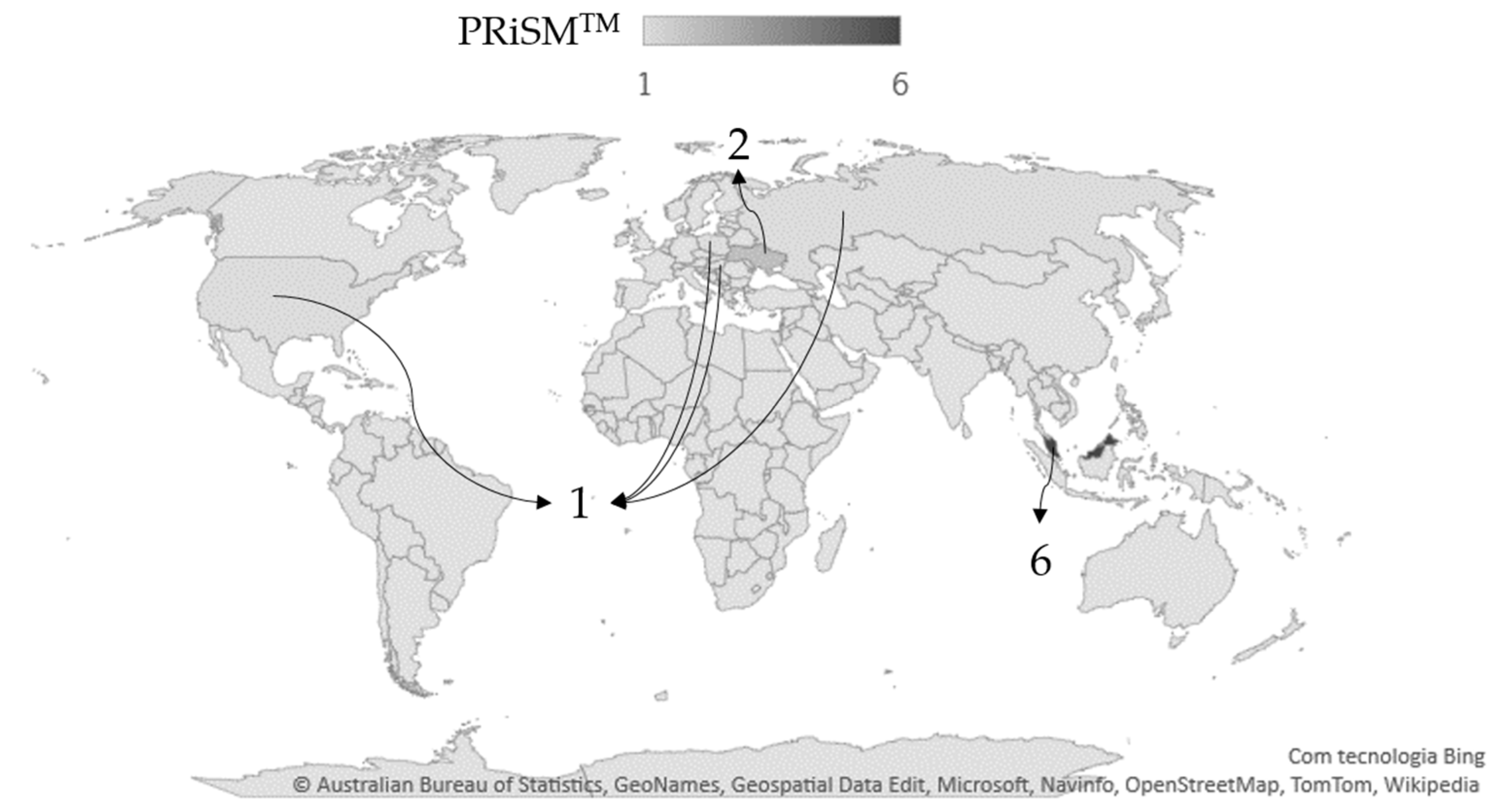

To analyze how the 20 selected publications are distributed throughout the world map - based on the identified country of publication - two graphs were produced (

Figure 28 and

Figure 29), one for articles referring to PM² and another for articles referring to PRiSM

TM.

By analyzing

Figure 28, it can be noted that most publications belong to the European continent. This fact may be due to the PM² methodology being developed by the European Commission. It should be noted that the only country which has a publication on this methodology and does not belong entirely to the European continent is Russia, a country which belongs to both the European and Asian continents. Another relevant fact is that Portugal is the country that has the most articles on the topic, with a total of four publications. However, three of these publications are related to the same theme, successful management in PM, and belong to the same authors [

92,

93,

94].

By analyzing

Figure 29, it can be verified that 50% of the previously selected publications on the PRiSM

TM methodology and the P5™ standard belong to Malaysia, a Southeast Asian country and that only four out of 12 total publications belong to Europe, not including Russia, a Euro-Asian country. Contrary to the PM² methodology, the selected publications mainly belong to continents other than the European continent. The GPM

® aims to encourage sustainable business and achieve the 2030 SDGs presented by the UN, an organization that is present all over the world. This may justify this dispersion across the globe.

Through the reading and analysis of the selected papers, some important considerations regarding the two methodologies under study were drawn. Some features concerning the PM² methodology are shown in

Table 6.

Through the table, it can be seen that, in the opinion of the authors of the publications, the most mentioned feature relates to the fact that the methodology includes best practices from other bodies of knowledge, followed by the fact that it is a free methodology.

On the other hand, an analysis of the same authors' articles was conducted to draw considerations concerning the PRiSM

TM methodology and the P5™ standard. The respective taxonomy was built, which resulted in

Table 7.

By analyzing

Table 7 it can be seen that the most mentioned feature is related to the fact that it is an extension of the TBL - profit, planet and people - since it also includes the product and the process, followed by the fact that the P5™ standard can be a training path, which includes sustainability, for engineering students.

4.2.3. Analysis based on interviews

This section presents the results obtained from the interviews conducted with a user of the PM² methodology and with Mr. Nicos Kourounakis, co-author of the PM² methodology.

Interview with a user of PM² methodology

This section presents the results obtained from an interview with a former researcher from the University of Minho who carried out a project, which involved the use of the PM² methodology.

Table 8 shows the key points from this interview.

Interview with Mr Nicos Kourounakis

Table 9 presents a summary table encompassing the key points of the interview with Mr Nicos Kourounakis.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to fill an existing gap in studies on sustainability in PM and to broaden the debate on the subject. This study also made it possible to analyse the presence of sustainability in PM guides and in scientific publications. Sustainability is a very topical issue, which is why it was decided to study a relatively recent sustainability-related PM methodology, PRiSM, in combination with another methodology. The methodology selected for the comparative analysis was PM² because it is also a relatively recent methodology and is freely available. To this end, the two methodologies were compared on the basis of their guides, and scientific publications about them were selected and analyzed. Finally, interviews were conducted on the PM² methodology. This study contributes to broadening readers' knowledge of these two methodologies and the integration of sustainability into PM.

With the analysis of the presence of sustainability in some current PM guides it was concluded that in PMBOK

®, PRINCE2

® and PM² the reference to sustainability is not significant. These results are in line with the statements made by Brones et al. (2014) [

83], Silvius and Schipper (2014) [

77] and Eskerod and Huemann (2013) [

76] related to PM best practices not considering environmental sustainability.

Through the analysis of the scientific publications present in the databases it was found that the United States has more publications on sustainability in PM and engineering is the area that produced more publications on this theme.

In addition, the number of articles found is considered to be relatively small, which is in line with the fact pointed out by Stanitsas et al. (2021) [

12], who justify this by stating that the area under analysis is relatively new and under development.

The main difference between the PM² and PRiSM

TM methodologies is their main objective. The PRiSM

TM methodology seeks to make the PM process more sustainable, while the PM² methodology aims to address the needs of institutions and projects belonging to the European Union. The project definitions of the two methodologies are very similar, however, PM² defines it as an organizational structure and PRiSM

TM as an investment. The PRiSM

TM methodology has two differentiating deliverables compared to other approaches, including PM², the P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan, which is in line with Carboni et al. (2018) [

29].

While in the PRiSMTM methodology, sustainability is very present in the project life cycle, in the PM² methodology this theme is not explicit in any of the project phases. The PRiSMTM methodology identifies and analyzes sustainability impacts, converts them into opportunities, and produces a sustainability analysis. The PM² methodology does not directly address the issue of sustainability in any of its phases. This may happen because the methodology aims to be generic and adaptable to any project and type of activity. Both PM² and PRiSMTM have the Business Case and the Requirements Document as deliverables. In general, the other deliverables seem to be quite similar in scope, but they have slightly different names. The Closure/Closing Phases are similar in both methodologies. Both methodologies, PM² and PRiSMTM, refer to success criteria, however, these are more developed in the PRiSMTM methodology.

The publications analyzed for the PM² methodology belong mostly to the European continent, which is expected since this methodology was developed by the European Commission. Contrary to what happens in PM², in the PRiSMTM methodology and P5™ standard, the publications belong mostly to other continents, being dispersed around the globe. The goal of the GPM® is to promote sustainable business and achieve the 17 SDGs by the horizon year 2030, as planned when it was created by the UN. Since the UN is a global organization, it is expected that there are publications all over the world, which was the case observed.

After analyzing the selected publications, it was found that the most mentioned feature regarding the PM² methodology is related to the fact that the methodology includes best practices from other bodies of knowledge, followed by the fact that it is an open and free methodology. Concerning the PRiSMTM methodology and P5™ standard it was found that the most mentioned characteristic is related to the fact that it is an extension of the Triple Bottom Line since it also includes the product and the process, followed by the fact that the P5™ standard can be a training path, which includes sustainability, for engineering students.

Lastly, through the interview with Mr Nicos Kourounakis and the user of PM² methodology, it was concluded that PM² methodology is intended to be generic and adaptable to any type of project. Therefore, adding sustainability to the PM² methodology might not be appropriate. However, users who choose to include sustainability in their PM and use another approach than PRiSMTM, such as the PM² methodology, can include it in the additional objectives of the project and use a sustainable-related deliverable, for example, the P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan. These templates are available online for free. Thus, it can be concluded that PRiSMTM is an option to complement PM² in terms of integrating sustainability with its differentiating products.

Due to the unavailability of schedules, it was not possible to conduct interviews with professionals who are used to working with/implement the PRiSMTM methodology, which is a limitation of this study. In future work, interviews with users and experts in the PRiSMTM methodology are planned.

6. Conclusions

Although PM best practices do not make reference to environmental sustainability, there is a new methodology that aims to make PM more sustainable, PRiSMTM. PM² is a PM methodology developed by the European Commission that aims to enable Project Managers to provide solutions and benefits to organizations. Although the PM² and PRiSMTM methodologies are relatively recent, they have very different objectives and characteristics. The first major difference between the two methodologies lies in their main objectives, PRiSMTM seeks to make the PM process more sustainable and PM² aims to meet the needs of institutions and projects belonging to the European Union. The P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan are the main differentiating deliverables in relation to other approaches such as PM². It is considered that these deliverables can be quickly and easily added to other PM approaches.

The PM² methodology does not take sustainability into account, as it aims to be a generic methodology that can be adapted to any project and type of activity, which was discovered through interviews with Mr Nicos Kourounakis and the user of the PM² methodology. In this way, this methodology is an example of a methodology in which sustainability and the deliverables mentioned above can be added to the scope of the project.

Both methodologies have positive and negative points according to the authors. The most cited characteristic in relation to PM² is related to the fact that the methodology includes best practices from other bodies of knowledge, followed by the fact that it is an open and free methodology. The most cited characteristic in relation to PRiSMTM and the P5™ standard is the fact that it is an extension of the Triple Bottom Line as it also includes the product and the process.

Finally, it is concluded that both methodologies are valid and advantageous. However, they are quite different and have different objectives. Furthermore, PRiSMTM is an option to complement PM² in order to integrate sustainability. To this end, sustainability can be added to the project’s additional objectives and the P5 Impact Analysis and the Sustainability Management Plan can be added to project deliverables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; methodology, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; software, P.F.S.; validation, P.M.S. and A.T.; formal analysis, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; investigation, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; resources, A.T.; data curation, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.; writing—review and editing, P.F.S. and A.T.; visualization, P.M., P.F.S. and A.T.; supervision, P.F.S. and A.T.; project administration, P.F.S. and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia within the R&D Units Project Scope: UIDB/00319/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sofia Lopes and Mr Nicos Kourounakis for their availability and fundamental contribution to this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Articles extracted from SCOPUS, Web of Science and B-on databases.

Table A1.

Articles extracted from SCOPUS, Web of Science and B-on databases.

| |

Authors |

Title of the document |

Database* |

| S |

W |

B |

| PM² |

Takagi and Varajão (2019) [110] |

Integration of success management into project management guides and methodologies - Position paper |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Pantouvakis (2017) [111] |

How can IPMA contribute to new PM² EU commission standard? |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Moya-Colorado et al. (2021) [112] |

The role of donor agencies in promoting standardized project management in the Spanish development non-government organizations |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Ribeiro-Lopes et al. (2022) [99] |

Application of the PM² Methodology in the Project Management of the Portuguese Project Management Observatory Creation - Initiating Phase |

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Takagi and Varajão (2020) [113] |

Success management in information systems projects - Work-in-progress |

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Takagi et al. (2019) [114] |

Integrating success management into EU PM² |

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Fiddicke et al. (2021) [115] |

A Phased Approach for preparation and organization of human biomonitoring studies |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Katunina and Fomina (2021) [116] |

In search of excellence in social entrepreneurship project management: experience and standards of the European Union |

|

|

✓ |

| PRiSMTM

|

(Piterska, Kolesnikov, et al., 2018) [117] |

Development of the Markovian model for the life cycle of a project's benefits |

✓ |

|

✓ |

| (Turan & Johan, 2016) [118] |

Assessing sustainability framework of automotive related industry in the Malaysia context based on GPM P5 standard |

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Piterska, Rudenko, et al. (2018) [119] |

Development of the method of formation of the architecture of the innovation program in the system "University -State-Business" |

✓ |

|

|

| Johan and Turan (2016) [120] |

Industrial training approach using GPM P5 Standard for Sustainability in Project Management: A framework for sustainability competencies in the 21st century |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Turan et al. (2016) [121] |

Development of Systematic Sustainability Assessment (SSA) for the Malaysian Industry |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Johan and Turan, 2016b) [122] |

The development of Sustainability Graduate Community (SGC) as a learning pathway for sustainability education - A framework for engineering programmes in Malaysia Technical Universities Network (MTUN) |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Wan Lanang et al. (2017) [123] |

Systematic Assessment Through Mathematical Model for Sustainability Reporting in Malaysia Context |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| (Trzeciak (2021) [124] |

Sustainable risk management in it enterprises |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Lanang et al. (2018) [125] |

Incorporating attitudinal parameter in assessing sustainability of Malaysia manufacturing industry |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Verba and Ivanov (2015) [126] |

Sustainable Development and Project Management: Objectives and Integration Results |

|

✓ |

✓ |

| Salcedo Díaz et al. (2016) [127] |

Corporative social responsibility: model of process development for products with base on PRiSM and the p5 strategy |

|

✓ |

✓ |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Interview scripts.

Table A2.

Interview scripts.

| Interviewee |

Previous PM² methodology masters’ researcher |

CEO of PM² Alliance - Mr. Nicos Kourounakis |

| Questions |

How many methodologies did you use before PM²?

How did you learn about PM²? Was it only for your thesis or did you know about it before? If it was only for your thesis, ask: Was it a university thesis proposal or did you choose to use it yourself?

Now I would like you to tell me about your experience of using the PM² methodology, what the project consisted of, and what it was like for you.

What are the main advantages that you have observed with the use of the methodology?

What are the main disadvantages you found with the use of the methodology?

What challenges have arisen or had to be overcome by using the methodology?

Did you use all the artefacts of the methodology? If not: Do you consider that some are not important or were not relevant to your project in particular?

One disadvantage presented by the authors relates to success management. The PM² methodology identifies success factors in the initiation phase and defines the criteria for evaluating project success in the planning phase. But after this identification and definition, PM² does not provide management activities on these artefacts, and there is no monitoring and control throughout the project. Do you think these aspects should be incorporated into the methodology?

What do you think is missing in the methodology, what do you think is important to be there and is not? Or do you think nothing is missing? Why?

Do you think that including sustainability in this methodology would be a topic to think about in the future and an added value? If yes, why?

Do you know the PRiSMTM methodology? And the P5™ of the GPM®?

Do you think there is anything else we should talk about this methodology or another topic that we haven't talked about yet that you think is important? |

After doing a literature review, it was found that sustainability is not found in almost any of the PM methodologies. Do you consider sustainability a relevant issue to be considered in PM?

Do you consider that incorporating sustainability in the next version of the PM² methodology would add value? If yes, how?

Are you familiar with the GPM® P5™? Do you think it could be used to complement the PM² methodology?

One of the disadvantages raised by some authors [92,93,94] is related to success management. The PM² methodology identifies the success factors in the initiation phase (in the Project Initiation Request and the Business Case) and defines the project success evaluation criteria in the planning phase, which are included in the Project Handbook. However, after this identification and definition, PM² does not provide management activities on these artefacts, there is no monitoring and control throughout the project. Why were these activities not considered? Do you consider that it could be a topic to think about in the next version?

As a solution to the issue, Takagi and Varajão (2019) [92] propose a success management process integrated into the PM² methodology. This integrative model aims to increase the robustness of success management and integrate the management of success criteria and factors into the planning, execution, closure, monitoring and control phases. What do you think about it?

Another disadvantage raised, by some authors [99], is related to the lack of clarity and difficulty in understanding the explanation of the artefacts, even with guidance. As a solution, the authors advocate adding a project example that includes all the completed documents. What are your thoughts on this?

Do you have anything else you would like to say about the PM² methodology that would be useful for research? |

References

- Fonseca, L.; Carvalho, F.; Santos, G. Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11904. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Addressing the SDGs in Sustainability Reports: The Relationship with Institutional Factors. J Clean Prod 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca; Carvalho The Reporting of SDGs by Quality, Environmental, and Occupational Health and Safety-Certified Organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5797. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhao, W.; Fu, B.; Meadows, M.E.; Pereira, P. Key Axes of Global Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. J Clean Prod 2023, 385, 135767. [CrossRef]

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Leopoulos, V. Integrating Sustainability Indicators into Project Management: The Case of Construction Industry. J Clean Prod 2021, 279, 123774. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Thuesen, C.; Geraldi, J. The Projectification of Everything: Projects as a Human Condition. Project Management Journal 2016, 47, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Vrchota, J.; Řehoř, P.; Maříková, M.; Pech, M. Critical Success Factors of the Project Management in Relation to Industry 4.0 for Sustainability of Projects. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G. Sustainability as a New School of Thought in Project Management. J Clean Prod 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.; Schipper, R. Sustainability in Project Management: A Literature Review and Impact Analysis. Social Business 2014, 4, 63–96. [CrossRef]

- Brones, F.; De Carvalho, M.M.; De Senzi Zancul, E. Ecodesign in Project Management: A Missing Link for the Integration of Sustainability in Product Development? J Clean Prod 2014, 80, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Leopoulos, V. Integrating Sustainability Indicators into Project Management: The Case of Construction Industry. J Clean Prod 2021, 279, 123774. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.H.; Nazzal, M.A.; Darras, B.M. A General Framework for Sustainability Assessment of Manufacturing Processes. Ecol Indic 2019, 97, 211–224. [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G. Sustainability as a New School of Thought in Project Management. J Clean Prod 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; 8th Ed.; Pearson: Harlow, 2019; ISBN 978-1292208787.

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; 8th Ed.; Pearson: Harlow, 2019; ISBN 978-1292208787.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Laursen, M.; Svejvig, P. Taking Stock of Project Value Creation: A Structured Literature Review with Future Directions for Research and Practice. International Journal of Project Management 2016, 34, 736–747. [CrossRef]

- Carboni, J.; Duncan, W.; Gonzalez, M.; Milsom, P.; Young, M. Sustainable Project Management - The GPM Reference Guide; GPM Global, Ed.; 2nd Ed.; 2018.

- IPMA ICB4 - Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management, Version 4.0; International Project Management Association: Nijkerk, 2015.

- PMI PMBOK Guide - Seventh Edition; Project Management Institute, Inc.: Newton Square, Pennsylvania, 2021; ISBN 9781628256642.

- AXELOS Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2®; 6th Ed.; 2017.

- PM2 ALLIANCE Metodologia de Gestão de Projetos - Guide 3.0; PM2 Alliance: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Pais Ribeiro, J.L. RESEARCH REVIEW AND SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE. Psicologia, Saúde & Doença 2014, 15. [CrossRef]

- Donato, H.; Donato, M. Stages for Undertaking a Systematic Review. Acta Med Port 2019, 32, 227–235. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, A.D.; Clarke, J.; Esmail, R.; Sinclair, S.; Irvin, E.; Bombardier, C. A Critical Review of Reviews on the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001, 26, E155–E162. [CrossRef]

- European Union Evolution of PM2.

- GPM Media Release: GPM Releases New P5 Standard for Sustainable Project Management.

- Carboni, J.; Duncan, W.; Gonzalez, M.; Milsom, P.; Young, M. Sustainable Project Management - The GPM Reference Guide; GPM Global, Ed.; 2nd Ed.; 2018.

- Silva, N.R. Normalização de Publicações Técnicas e/Ou Científicas: Guia Prático Para Docentes, Pesquisadores e Discentes de Cursos Técnicos, Superiores e Pós-Graduação: Atualizado Conforme a Norma ABNT NBR 6023/2018; 1a Ed.; Editora Appris, 2021; ISBN 9786525005188.

- Nogueira, A. Metodologia Do Trabalho Científico 2015.

- Moura, D.L. Pesquisa Qualitativa: Um Guia Prático Para Pesquisadores Iniciantes; 1a Ed.; Editora CRV, 2021; ISBN 9786558686118.

- Kerzner, H. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling; 12th Ed.; Wiley, 2017; ISBN 978-1119165354.

- Tuman, G.J. Development and Implementation of Effective Project Management Information and Control Systems. In Project Management Handbook; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, 1983; pp. 495–532.

- Kerzner, H. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling; 12th Ed.; Wiley, 2017; ISBN 978-1119165354.

- PM2 ALLIANCE Metodologia de Gestão de Projetos - Guide 3.0; PM2 Alliance: Luxembourg, 2018.

- APM APM Body of Knowledge; 6th Ed.; Association for Project Management: Reino Unido, 2012; ISBN 978-1-903494-82-0.

- APM APM Body of Knowledge; 6th Ed.; Association for Project Management: Reino Unido, 2012; ISBN 978-1-903494-82-0.

- IPMA ICB4 - Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management, Version 4.0; International Project Management Association: Nijkerk, 2015.

- Munns, A.K.; Bjeirmi, B.F. The Role of Project Management in Achieving Project Success. International Journal of Project Management 1996, 14, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R. Projectification and Its Impact on Societal Development in Germany. PM World Journal 2020, 2330–4480.

- Wagner, R. Projectification and Its Impact on Societal Development in Germany. PM World Journal 2020, 2330–4480.

- Midler, C. “Projectification” of the Firm: The Renault Case. Scandinavian Journal of Management 1995, 11, 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Thuesen, C.; Geraldi, J. The Projectification of Everything: Projects as a Human Condition. Project Management Journal 2016, 47, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.; Bosch-Rekveldt, M.; Pesämaa, O. Moving Goals and Governance in Megaprojects. International Journal of Project Management 2023, 41, 102486.

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development. In The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press, 2015 ISBN 0231173148.

- WCED Our Common Future; First Ed.; Oxford University Press, Oxford, GB, 1987; ISBN 019282080X.

- Starik, M.; Rands, G.P. Weaving An Integrated Web: Multilevel and Multisystem Perspectives of Ecologically Sustainable Organizations. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9512280025 1995, 20, 908–935.

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. The Academy of Management Review 1995, 20, 986. [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, C.; Sierra, V.; Rodon, J. Sustainable Operations: Their Impact on the Triple Bottom Line. Int J Prod Econ 2012, 140, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC; Stony Creek, CT, 1998; ISBN 0865713928 9780865713925.

- Dalibozhko, A.; Krakovetskaya, I. Youth Entrepreneurial Projects for the Sustainable Development of Global Community: Evidence from Enactus Program. SHS Web of Conferences 2018, 57, 1009. [CrossRef]

- Schieg, M. The Model of Corporate Social Responsibility in Project Management. Verslas: teorija ir praktika 2009, 315–321.

- Gimenez, C.; Sierra, V.; Rodon, J. Sustainable Operations: Their Impact on the Triple Bottom Line. Int J Prod Econ 2012, 140, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- UNCSD Indicators of Sustainable Development: Guidelines and Methodologies.; United Nations, 2001.

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.-S. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of management Review 1995, 20, 874–907.