Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

28 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

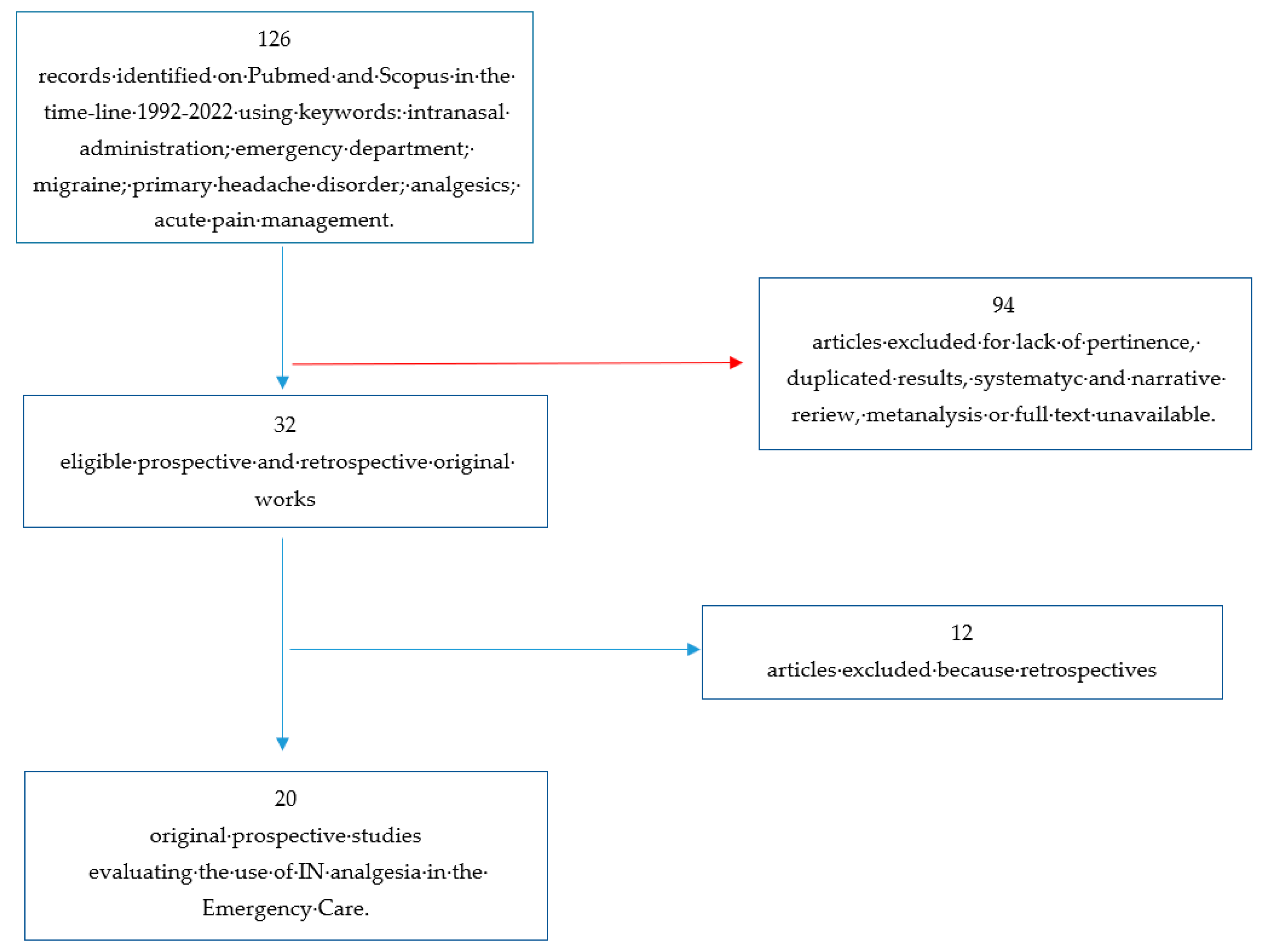

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Headache

3.2. Trauma and injuries

3.3. Renal colic

3.4. Other situations

3.4.1. Prehospital

3.4.2. Breakthrough cancer pain

3.4.3. Acute pain (back and abdominal pain)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Summary

References

- Saunders M, Adelgais K, Nelson D. Use of intranasal fentanyl for the relief of pediatric orthopedic trauma pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Nov;17(11):1155-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, Tanabe P; PEMI Study Group. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain. 2007 Jun;8(6):460-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, DL. Emergency Departments Increasingly Administering Medications through the Nose. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017 Nov-Dec;37:132-133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires A, Fortuna A, Alves G, Falcão A. Intranasal drug delivery: how, why and what for? J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2009;12(3):288-311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole J, Shepherd M, Young P. Intranasal fentanyl in 1-3-year-olds: a prospective study of the effectiveness of intranasal fentanyl as acute analgesia. Emerg Med Australas. 2009 Oct;21(5):395-400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin B, Wiafe J, Ciaramella C, Valdez L, Motov SM. The use of intranasal analgesia for acute pain control in the emergency department: A literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Feb;36(2):310-318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Silberstein S, Winner PK, McAllister PJ, Tepper SJ, Halker R, Mahmoud RA, Siffert J. Early Onset of Efficacy and Consistency of Response Across Multiple Migraine Attacks From the Randomized COMPASS Study: AVP-825 Breath Powered® Exhalation Delivery System (Sumatriptan Nasal Powder) vs Oral Sumatriptan. Headache. 2017 Jun;57(6):862-876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodick D, Brandes J, Elkind A, Mathew N, Rodichok L. Speed of onset, efficacy and tolerability of zolmitriptan nasal spray in the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(2):125-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith JT, Wait S, Brewer KL. A prospective double-blind study of nasal sumatriptan versus IV ketorolac in migraine. Am J Emerg Med. 2003 May;21(3):173-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avcu N, Doğan NÖ, Pekdemir M, Yaka E, Yılmaz S, Alyeşil C, Akalın LE. Intranasal Lidocaine in Acute Treatment of Migraine: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Jun;69(6):743-751. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benish T, Villalobos D, Love S, Casmaer M, Hunter CJ, Summers SM, April MD. The THINK (Treatment of Headache with Intranasal Ketamine) Trial: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Intranasal Ketamine with Intravenous Metoclopramide. J Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;56(3):248-257.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarvari HR, Baigrezaii H, Nazarianpirdosti M, Meysami A, Safari-Faramani R. Comparison of the efficacy of intranasal ketamine versus intravenous ketorolac on acute non-traumatic headaches: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Head Face Med. 2022 Jan 3;18(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha R, Pant S, Shrestha A, Batajoo KH, Thapa R, Vaidya S. Intranasal ketamine for the treatment of patients with acute pain in the emergency department. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7(1):19-24. [CrossRef]

- Shimonovich S, Gigi R, Shapira A, Sarig-Meth T, Nadav D, Rozenek M, West D, Halpern P. Intranasal ketamine for acute traumatic pain in the Emergency Department: a prospective, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. BMC Emerg Med. 2016 Nov 9;16(1):43. [CrossRef]

- Blancher M, Maignan M, Clapé C, et al. Intranasal sufentanil versus intravenous morphine for acute severe trauma pain: A double-blind randomized non-inferiority study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(7):e1002849. Published 2019 Jul 16. [CrossRef]

- Chew KS, Shaharudin AH. An open-label randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of adding intranasal fentanyl to intravenous tramadol in patients with moderate to severe pain following acute musculoskeletal injuries. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(10):601-605. [CrossRef]

- Lemoel F, Contenti J, Cibiera C, Rapp J, Occelli C, Levraut J. Intranasal sufentanil given in the emergency department triage zone for severe acute traumatic pain: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Intern Emerg Med. 2019 Jun;14(4):571-579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tongbua S, Sri-On J, Thong-On K, Paksophis T. Non-inferiority of intranasal ketamine compared to intravenous morphine for musculoskeletal pain relief among older adults in an emergency department: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2022 Mar 1;51(3):afac073. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golzari SE, Soleimanpour H, Rahmani F, Zamani Mehr N, Safari S, Heshmat Y, Ebrahimi Bakhtavar H. Therapeutic approaches for renal colic in the emergency department: a review article. Anesth Pain Med. 2014 Feb 13;4(1):e16222. [CrossRef]

- Farnia MR, Jalali A, Vahidi E, Momeni M, Seyedhosseini J, Saeedi M. Comparison of intranasal ketamine versus IV morphine in reducing pain in patients with renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Mar;35(3):434-437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouraghaei M, Moharamzadeh P, Paknezhad SP, Rajabpour ZV, Soleimanpour H. Intranasal ketamine versus intravenous morphine for pain management in patients with renal colic: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. World J Urol. 2021 Apr;39(4):1263-1267. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili M, Shirani F, Entezari P, Hedayatshodeh M, Baigi V, Mirfazaelian H. Desmopressin/indomethacin combination efficacy and safety in renal colic pain management: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Jun;37(6):1009-1012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozafari J, Maleki Verki M, Motamed H, Sabouhi A, Tirandaz F. Comparing intranasal ketamine with intravenous fentanyl in reducing pain in patients with renal colic: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Mar;38(3):549-553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazemian N, Torabi M, Mirzaee M. Atomized intranasal vs intravenous fentanyl in severe renal colic pain management: A randomized single-blinded clinical trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;38(8):1635-1640. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickard C, O’Meara P, McGrail M, Garner D, McLean A, Le Lievre P. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal fentanyl vs intravenous morphine for analgesia in the prehospital setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2007 Oct;25(8):911-7. [CrossRef]

- Andolfatto G, Innes K, Dick W, Jenneson S, Willman E, Stenstrom R, Zed PJ, Benoit G. Prehospital Analgesia With Intranasal Ketamine (PAIN-K): A Randomized Double-Blind Trial in Adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;74(2):241-250. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banala SR, Khattab OK, Page VD, Warneke CL, Todd KH, Yeung SJ. Intranasal fentanyl spray versus intravenous opioids for the treatment of severe pain in patients with cancer in the emergency department setting: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020 Jul 10;15(7):e0235461. [CrossRef]

- Sin B, Jeffrey I, Halpern Z, Adebayo A, Wing T, Lee AS, Ruiz J, Persaud K, Davenport L, de Souza S, Williams M. Intranasal Sufentanil Versus Intravenous Morphine for Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Pilot Trial. J Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;56(3):301-307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Snieneh HM, Alsharari AF, Abuadas FH, Alqahtani ME. Effectiveness of pain management among trauma patients in the emergency department, a systematic review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2022 May;62:101158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi-Hiebl S, Ndieyira JW, Al Enzi Y, Al Akkad W, Koch T, Geldner G, Reyher C, Eberhart LHJ. Pharmacokinetic Characterisation and Comparison of Bioavailability of Intranasal Fentanyl, Transmucosal, and Intravenous Administration through a Three-Way Crossover Study in 24 Healthy Volunteers. Pain Res Manag. 2021 Nov 29;2021:2887773. [CrossRef]

- Nave R, Schmitt H, Popper L. Faster absorption and higher systemic bioavailability of intranasal fentanyl spray compared to oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate in healthy subjects. Drug Deliv. 2013 Jun-Jul;20(5):216-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez AR, Bourn SS, Crowe RP, Bronsky ES, Scheppke KA, Antevy P, Myers JB. Out-of-Hospital Ketamine: Indications for Use, Patient Outcomes, and Associated Mortality. Ann Emerg Med. 2021 Jul;78(1):123-131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzer N, McLeod SL, Walsh C, Grewal K. Low-dose Ketamine For Acute Pain Control in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2021 Apr;28(4):444-454. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016 Jul;37(7):865-72. [CrossRef]

- Zanza C, Piccolella F, Racca F, Romenskaya T, Longhitano Y, Franceschi F, Savioli G, Bertozzi G, De Simone S, Cipolloni L, La Russa R. Ketamine in Acute Brain Injury: Current Opinion Following Cerebral Circulation and Electrical Activity. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Mar 17;10(3):566. [CrossRef]

- Zanza C, Romenskaya T, Zuliani M, Piccolella F, Bottinelli M, Caputo G, Rocca E, Maconi A, Savioli G, Longhitano Y. Acute Traumatic Pain in the Emergency Department. Diseases. 2023 Mar 3;11(1):45. [CrossRef]

- Bouida W, Bel Haj Ali K, Ben Soltane H, Msolli MA, Boubaker H, Sekma A, Beltaief K, Grissa MH, Methamem M, Boukef R, Belguith A, Nouira S. Effect on Opioids Requirement of Early Administration of Intranasal Ketamine for Acute Traumatic Pain. Clin J Pain. 2020 Jun;36(6):458-462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green SM, Roback MG, Kennedy RM, Krauss B. Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation: 2011 update. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 May;57(5):449-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassin-Delyle S, Buenestado A, Naline E, Faisy C, Blouquit-Laye S, Couderc LJ, Le Guen M, Fischler M, Devillier P. Intranasal drug delivery: an efficient and non-invasive route for systemic administration: focus on opioids. Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Jun;134(3):366-79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoust R, Paquet J, Cournoyer A, Piette È, Morris J, Lessard J, Castonguay V, Williamson D, Chauny JM. Side effects from opioids used for acute pain after emergency department discharge. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Apr;38(4):695-701. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanza C, Longhitano Y, Lin E, Luo J, Artico M, Savarese B, Bonato V, Piccioni A, Franceschi F, Taurone S, Abenavoli L, Berger JM. Intravenous Magnesium - Lidocaine - Ketorolac Cocktail for Postoperative Opioid Resistant Pain: A Case Series of Novel Rescue Therapy. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2021;16(3):288-293. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Gri N, Bavestrello Piccini G, Longhitano Y, Zanza C, Piccioni A, Esposito C, Ricevuti G, Bressan MA. Emergency Department Overcrowding: Understanding the Factors to Find Corresponding Solutions. J Pers Med. 2022 Feb 14;12(2):279. [CrossRef]

- Zanza C, Tornatore G, Naturale C, Longhitano Y, Saviano A, Piccioni A, Maiese A, Ferrara M, Volonnino G, Bertozzi G, Grassi R, Donati F, Karaboue MAA. Cervical spine injury: clinical and medico-legal overview. Radiol Med. 2023 Jan;128(1):103-112. [CrossRef]

| First Author | Randomization process | Deviation from intended intervention | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodich et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Meredith et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Avcu et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Benish et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sarvai et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Shrestha et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Shimonovic et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Blancher et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chew et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Leomoel et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tongbual et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Silberstein et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pouraghaei et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Jalili et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mozafari et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nazemian et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rickard et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Andolfatto et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Banala et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sin et al |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Author | Year | Intervention | Population | Objective | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodick et al | 2005 | IN zolmitriptan for headache | afer exclusions 1740; 886 zolmitriptan, 854 placebo | Headache reduction at 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h | Response rate superior in zolmitriptan (66,2%) vs placebo (35,0%) p<0,001 |

| Meredith et al | 2003 | IN zolmitriptan vs IV ketorolac for headache | 29; 16 sumatriptan, 13 ketorolac | Headache reduction at 1 h | Both achieved significant pain reduction, however ketorolac was superior in reducing VAS |

| Avcu et al | 2017 | IN lidocaine for headache | after exclusion 162; 81 lidocaine, 81 placebo | Headache reduction at 15 and 30 min | No difference in pain reduction |

| Benish et al | 2019 | IN ketamine vs IV metoclopramide for headache | after exclusion 53; 27 ketamine, 26 placebo | Headache reduction at 30 min and requirement for rescue analgesia at 60 min | No difference in pain reduction |

| Sarvari et al | 2022 | IN ketamine vs IV ketorolac for headache | afer exclusions 140; 70 ketamine, 70 ketorolac | Headache reduction at 30, 60, 120 min | Ketamine had more analgesic effect than intravenous ketorolac in a shorter time |

| Shrestha et al | 2016 | Effectiveness of IN ketamine in pain reduction (various acute injuries) | 39 patients | Pain reduction at 15, 30, 60 min | IN ketamine reduced VAS pain scores to a clinically significant degree in 80% of patients |

| Shimonovic et al | 2016 | IN ketamine vs IV morphine vs IM morphine in acute traumatic pain | 90 patients; 34 IN ketamine, 26 IV morphine, 30 IM morphine | Pain at 5 min interval from 0 to 60 min | IN ketamine may provide analgesia clinically equal to IV or IM morphine |

| Blancher et al | 2019 | IN sufentanil vs IV morphine in acute pain | 157 patients; 77 IN sufentanil, 80 IV morphine | Non-inferiority study | IN sufentanil was non-inferior to IV morphine |

| Chew et al | 2017 | IN fentanil plus IV tramadol vs IV tramadol in acute pain | 20 patients; 10 IN fentanil plus IV tramadol, 10 IV tramadol | Pain reduction at 10 min | Greater reduction in the mean VAS score among the patients in the fentanyl + tramadol arm |

| Lemoel et al | 2019 | IN sufentanil vs IN placebo in acute pain (all plus IV multimodal analgesia) | 144 patients; 72 IN sufentanil, 72 IN placebo | Proportion of VAS < 3 at 30 min | IN sufentanil determines a 20% absolute increase in proportion of patients reaching pain relief |

| Tongbual et al | 2022 | IN ketamine vs IV morphine in musculoskeletal pain in ED | 74 patients; 37 IN ketamine, 37 IN morphine | Pain reduction at 30 min | IN ketamine provides analgesic efficacy comparable (non-inferior) to IV morphine |

| Silberstein et al | 2017 | Sumatriptan nasal powder (with IN delivery system) vs oral sumatriptan in migraine | 1531 migraine events; 765 nasal powder, 766 oral sumatriptan | Headache reduction at 30 min | Sumatriptan powder provided greater reduction in migraine pain intensity |

| Pouraghaei et al | 2021 | IN ketamine vs IV morphine in renal colic | 200 patients; 100 IN ketamine, 100 IV morphine | Pain reduction at 15, 30, 60 min | IN ketamine has the same efcacy as IV morphine in renal colic pain control |

| Jalili et al | 2019 | Indomethacin plus IN desmopressin vs indomethacin plus IN placebo in renal colic | 124 patients; 62 IN desmopressin, 62 IN placebo | Pain reduction | Desmopressin as an adjunct to NSAIDs in the management of renal colic, does not significantly improve pain relief |

| Mozafari et al | 2020 | IN ketamine vs IV fentanil in renal colic | 130 patients; 65 IN ketamine, 65 IV fentanil | Pain reduction at 5, 15, 30 min | The effect of IN ketamine was less significant than of IV fentanil |

| Nazemian et al | 2020 | IN fentanil plus IV ketorolac vs IV fentanil plus IV ketorolac in renal colic | 220 patients; 110 IN fentanil, 110 IV fentanil | Pain reduction at 60 min | The mean pain score was higher in the IN group. Nevertheless, the pain intensity significantly and consecutively reduced in bothg roups during the study |

| Rickard et al | 2007 | IV morphine vs IN fentanil in prehospital analgesia | 258 patients; 122 IV morphine, 136 IN fentanil | Difference between baseline and destination pain score | No difference in pain reduction |

| Andolfatto et al | 2019 | Effectiveness of IN ketamine in pain reduction in prehospital setting | 120 patients; 60 IN ketamine, 60 IN placebo | Pain reduction at 2 and 30 min | Intranasal ketamine provides clinically significant pain reduction and improved comfort compared with intranasal placebo |

| Banala et al | 2020 | IN fentanil vs IV hydromorphone in cancer pain in ED setting | 82 patients; 42 IN fentanil, 42 IV hydromorphone | Pain reduction at 60 min | Two of three analyses supported non-inferiority of INF versus IVH, while one analysis was inconclusive |

| Sin et al | 2019 | IN sufentanil vs IV morphine in acute pain in ED | 60 patients; 30 IN sufentanil, 30 IV morphine | Efficacy and safety of IN sufentanil in ED | IN resulted in safe analgesia, comparable with IV morphine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).