Submitted:

26 August 2023

Posted:

28 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1

2.1.1. Content validity

2.1.2. Face validity

2.2. Phase 2

2.2.1. Design

2.2.2. Study population

2.2.3. Sampling and sample size

2.2.4. Data collection tool and variables of the study

2.2.5. Data collection

2.2.6. Data analysis and interpretation

2.2.7. Ethical considerations

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1

3.1.1. Content Validity

3.1.2. Face validity and pilot study in a target population

3.2. Phase 2

3.2.1. Descriptive analysis of the sample and the items

3.2.2. Construct validity by factor analysis

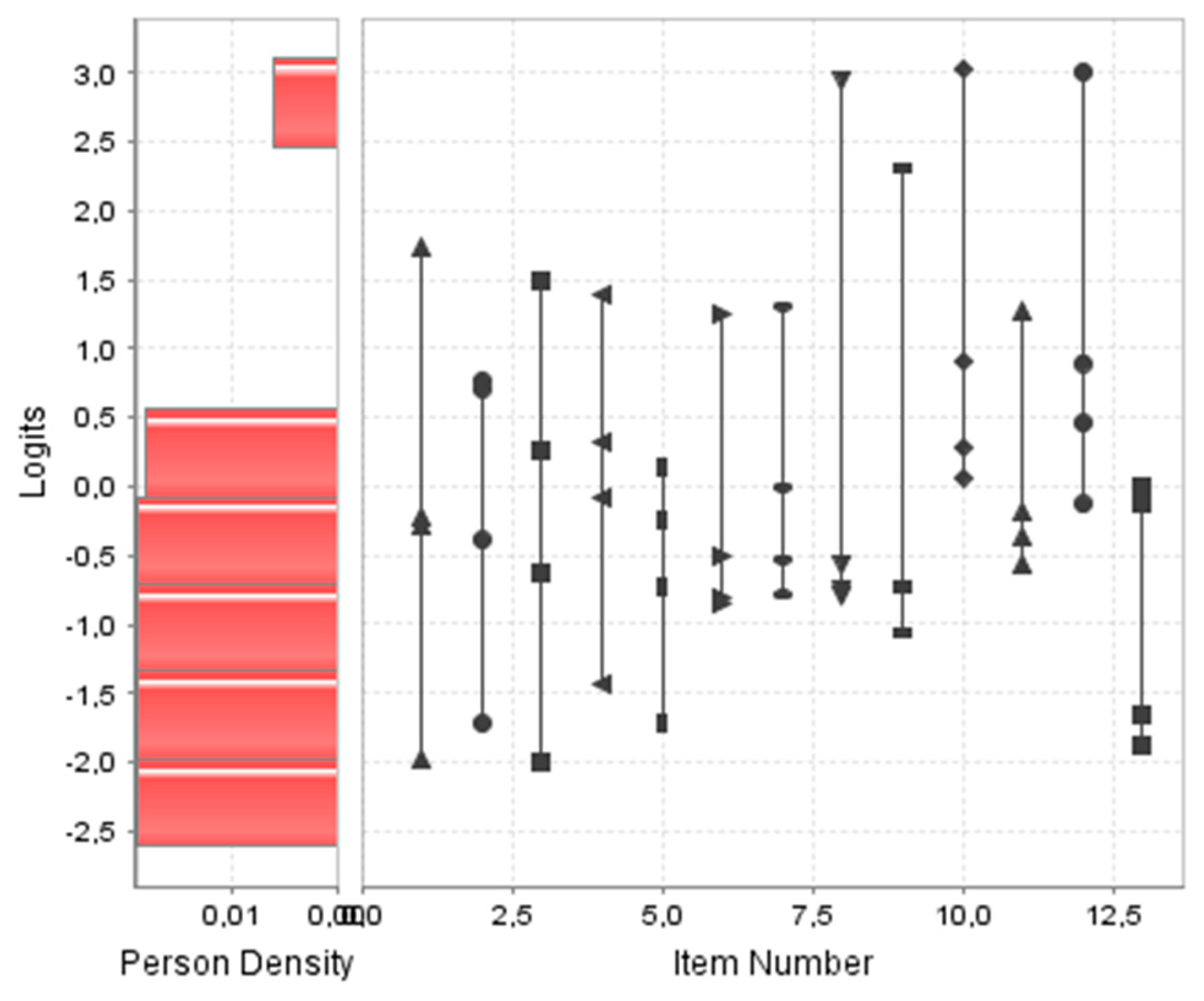

3.2.3. Construct-structural validity by Rasch analysis

3.2.4. Reliability

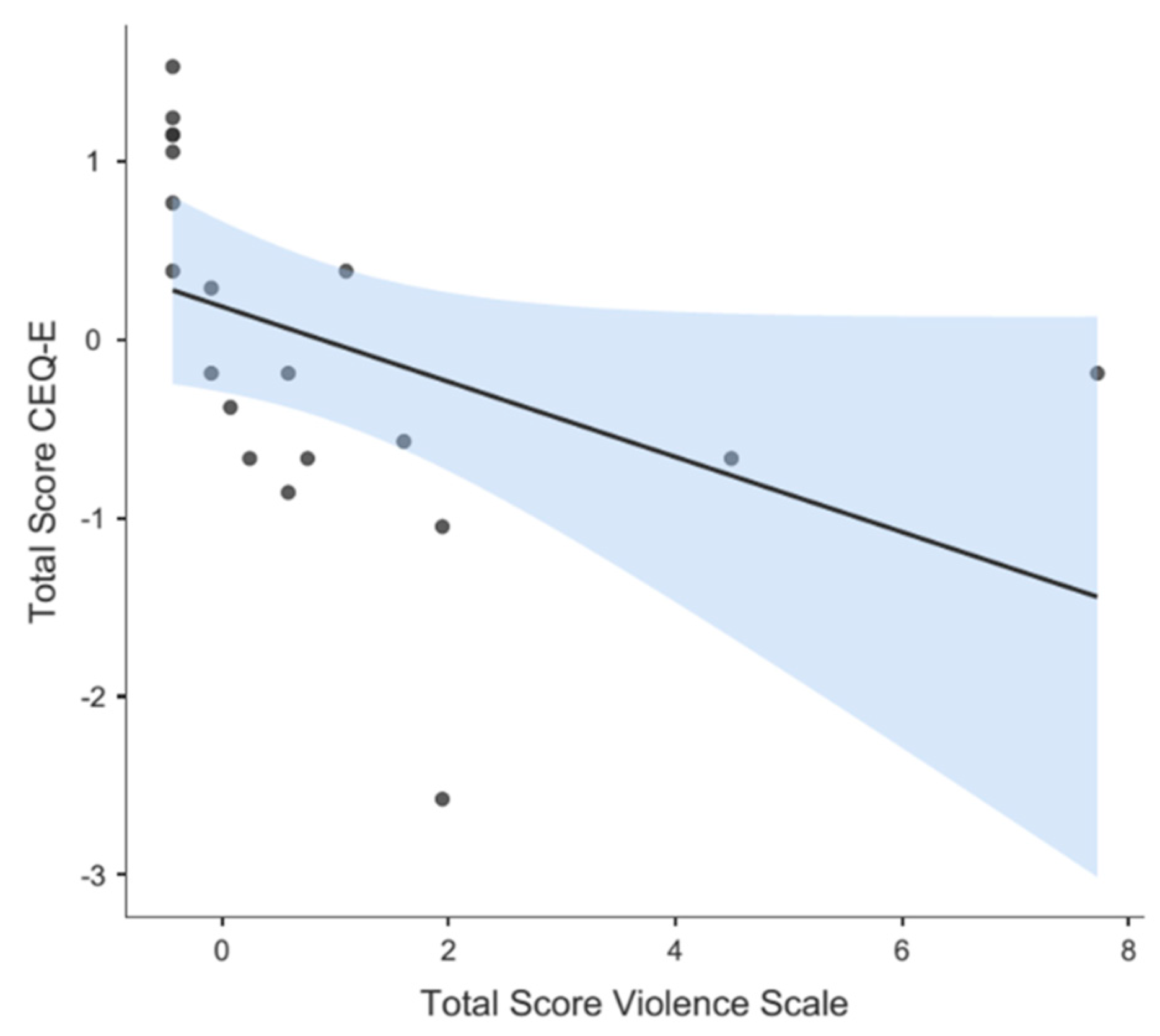

3.2.5. Divergent validity

3.2.6. Final proposed scale and known groups validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J. Obstetric violence in Spain (Part I): Women’s perception and interterritorial differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Roman, P.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Rodriguez-Arrastia, M.; Gutiérrez-Cascajares, L.; Ropero-Padilla, C. Experiences with obstetric violence among healthcare professionals and students in Spain: A constructivist grounded theory study. Women Birth. 2023, 36, e219–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darilek, U. ; A Woman's Right to Dignified, Respectful Healthcare During Childbirth: A Review of the Literature on Obstetric Mistreatment. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, V.; Castro, A. Measuring mistreatment of women during childbirth: a review of terminology and methodological approaches. Reprod Health. 2017, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betron, M.L.; McClair, T.L.; Currie, S.; Banerje, J. Expanding the agenda for addressing mistreatment in maternity care: a mapping review and gender analysis. Reprod Health. 2018, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Mir, J.; Martínez Gandolfi, A. La violencia obstétrica: una práctica invisibilizada en la atención médica en España [Obstetric violence. A hidden practice in medical care in Spain]. Gac Sanit. 2021, 35, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Cuauro, J.C. Obstetric violence: a hidden dehumanizing practice, exercised by medical care personnel: Is it a public health and human rights problem?. Rev Mex Med Forense. 2019,4,1-11. WHO. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth.

- WHO statement. World Health Organ [Internet]. 2015,4. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_cze.pdf.

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Rubio-Álvarez, A.; Ortiz-Esquinas, I.; Ballesta-Castillejos, A.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Obstetric Violence from a Midwife Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, A. The nature of obstetric violence and the organisational context of its manifestation in India: a systematic review. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021, 29, 2004634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part II): Interventionism and Medicalization during Birth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, X.; Carroli, G.; Garner, P. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 2, CD000081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, J.M; Weidman, A.; Huynh, S.; Delgado, D.; Easthausen, I.; Kaur, G. Painful gynecologic and obstetric complications of female genital mutilation/cutting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G.M.V.; Hosoume, R.S.; de Castro Monteiro, M.V.; Juliato, C.R.T.; Brito, L.G.O. Selective episiotomy versus no episiotomy for severe perineal trauma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2020, 31, 2291–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabot, S.C. We birth with others: Towards a Beauvoirian understanding of obstetric violence. Eur J Womens Stud, 2021, 28, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, M.; Santos, M.J.; Ruiz-Berdún, D.; Rojas, G.L.; Skoko, E.; Gillen, P.; Clausen, J.A. Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters. 2016, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C., Saraiva Coneglian, F.; Diniz, A.L.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Javadi, D.; Oladapo, O.T.; Khosla, R.; Hindin, M.J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Krewski, D.; Wen, S.W.; Zhang, L.; Xie, R.H. The incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder following traumatic childbirth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023, 162, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, D.; Hingray, C.; Burlacu, E.; Sterlé, A.; El-Hage, W. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry. 2021, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T.; Gable, R.K. A mixed methods study of secondary traumatic stress in labor and delivery nurses. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 747–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshef, S.; Mouadeb, D.; Sela, Y.; Weiniger, F.C.; Freedman, S.A. Childbirth, trauma and family relationships. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2157481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vázquez, S.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M. Relationship between perceived obstetric violence and the risk of postpartum depression: An observational study. Midwifery. 2022, 108, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuther, M.L. Prevalence of Obstetric Violence in Europe: Exploring Associations with trust, and care-Seeking Intention. Bachelor's thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands, August 3, 2021.

- Miller, S.; Lalonde, A. The global epidemic of abuse and disrespect during childbirth: History, evidence, interventions, and FIGO's mother-baby friendly birthing facilities initiative. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015, 131, S49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Carasso, K.B.; Kabakian-Khasholian, T. Exposing Obstetric Violence in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Review of Women's Narratives of Disrespect and Abuse in Childbirth. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022, 3, 850796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R.V.; Solórzano, E.H.; Iñiguez, M.M.; Monreal, L.M.A. Nueva evidencia a un viejo problema: El abuso de las mujeres en las salas de parto. Rev. Conamed. 2015, 18, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Terán, P.; Castellanos, C.; Gonzalez Blanco, M.; Ramos, D. Violencia obstétrica: Percepción de las usuarias. Rev Obstet Ginecol Venez. 2013, 73, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Molla, W.; Wudneh, A.; Tilahun, R. Obstetric violence and associated factors among women during facility based childbirth at Gedeo Zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022, 22, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sando, D.; Ratcliffe, H.; McDonald, K.; Spiegelman, D.; Lyatuu, G.; Mwanyika-Sando, M.; Emil, F.; Wegner, M.N.; Chalamilla, G.; Langer, A. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalley, A.A. “We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana. Women. 2023, 3, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, A.C.; Sim-Sim, M.; Almeida, V.S.; Zangão, M.O. Analysis of the Concept of Obstetric Violence: Scoping Review Protocol. J Pers Med. 2022, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Cervera-Gasch, Á. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part III): Healthcare Professionals, Times, and Areas. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahnberg, I.M.; Wijma, B. The NorVold Abuse Questionnaire (NorAQ): validation of new measures of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and abuse in the health care system among women. Eur J Public Health. 2003, 13, 361–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, P.; Gamble, J.; Creedy, D.K.; Newnham, E. Development of a tool to assess students' perceptions of respectful maternity care. Midwifery. 2022, 105, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, P.; Creedy, D.K.; Gamble, J.; Newnham, E.; McInnes, R. Effectiveness of an online education intervention to enhance student perceptions of Respectful Maternity Care: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022, 114, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çamlibel, M.; Uludağ, E. The Turkish version of the students' perceptions of respectful maternity care scale: An assessment of psychometric properties. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023, 70, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Cervera-Gasch, A.; Alemany-Anchel, M.J.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; González-Chordá, V.M. Design and Validation of the PercOV-S Questionnaire for Measuring Perceived Obstetric Violence in Nursing, Midwifery and Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Alemany-Anchel, M.J.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Peris-Ferrando, E.; Mahiques-Llopis, J.; González-Chordá, V.M. Perception of obstetric violence in a sample of Spanish health sciences students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022, 110, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biurrun-Garrido, A.; Brigidi, S.; Mena-Tudela, D. Perception of health sciences and feminist medical students about obstetric violence. Enferm Clin (Engl Ed). 2023, 33, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, M.; Salinero, S. Validación de la escala de violencia obstétrica y pruebas de la invarianza factorial en una muestra de mujeres chilenas. Interdisciplinaria. 2021, 38, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Parto es nuestro. Test de violencia obstétrica. Available online: https://www.elpartoesnuestro.es/blog/2014/08/18/test-de-violencia-obstetrica. (Accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Penfield, R.D.; Giacobbi, P.R. Jr. Applying a score confidence interval to Aiken’s item content-relevance index. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science. 2004, 8, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cantalejo, I.M.; Simón-Lorda, P.; Melguizo, M.; Escalona, I.; Marijuán, M.I.; Hernando, P. Validación de la Escala INFLESZ para evaluar la legibilidad de los textos dirigidos a pacientes. Anales Sis San Navarra. 2008, 31, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Hernández-Dorado, A.; Muñiz, J. [Decalogue for the Factor Analysis of Test Items]. Psicothema. 2022, 34, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. Exploratory Item Factor Analysis: a practical guide revised and updated. Anal. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Oliver-Roig, A.; Cabrero-García, J.; Congost-Maestre, N.; Dencker, A.; Richart-Martínez, M. The Spanish version of the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ-E): reliability and validity assessment. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016, 16, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-de la Torre, H.; Miñarro-Jiménez, S.; Palma-Arjona, I.; Jeppesen-Gutierrez, J.; Berenguer-Pérez, M.; Verdú-Soriano, J. Perceived satisfaction of women during labour at the Hospital Universitario Materno-Infantil of the Canary Islands through the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ-E). Enferm Clin (Engl Ed). 2021, 31, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. The exploratory factor analysis of items: guided analysis based on empirical data and software. Anal. Psicol. 2017, 33, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O. Rethinking Construct Reliability within Latent Variable Systems. In: Structural equation modeling: Present and future.; Cudeck, R..; du Toit, S.; Sörbom, D., Eds; Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software, United States of America, 2001; pp. 195-216.

- Ferrando, P. J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Assessing the quality and appropriateness of factor solutions and factor score estimates in exploratory item factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 2018, 78, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences,2nd. ed.; Mahwah. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, United States of America, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.B.; Makransky, G.; Horton, M. Critical Values for Yen’s Q3: Identification of Local Dependence in the Rasch Model Using Residual Correlations. Appl Psychol Meas. 2017, 41, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Mir, J.; Martínez Gandolfi, A. Obstetric violence denied in Spain. Enferm Clin (Engl Ed). 2022,32 Suppl 1,S82-S83. [CrossRef]

- Khsim, I.E.F.; Rodríguez, M.M.; Riquelme Gallego. B.; Caparros-González, R.A.; Amezcua-Prieto, C. Risk Factors for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after Childbirth: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 12, 2598. [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.M.; Segovia, J.L. [Confidence intervals for the content validity: A Visual Basic computer program for the Aiken's V]. Anal. Psicol. 2009, 25, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Charter, R. A. A breakdown of reliability coefficients by test type and reliability method and the clinical implications of low reliability. J Gen Psychol. 2003 Jul;130(3):290-304. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.; McDonald, R.P. NOHARM: Least squares item factor analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 1988, 23, 267–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. El Análisis Factorial Exploratorio de los Ítems: algunas consideraciones adicionales. Anal. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord FM. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems, 1st. ed.; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; New York, USA, 2012.

- Escobar Bravo, M.A. Adaptación transcultural de instrumentos de medida relacionados con la salud. Enferm Clin. 2004, 14, 102–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, M.; Kottorp, A.; Suhonen, R. The use and quality of reporting of Rasch analysis in nursing research: A methodological scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022, 132, 104244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we'll take it from here. Psychol Methods. 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Martínez-Vazquez, S.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Hernández-Martinez, A. The magnitude of the problem of obstetric violence and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth. 2021, 34, e526–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOE-A-2002-22188. Ley 41/2002, de 14 de noviembre, básica reguladora de la autonomía del paciente y de derechos y obligaciones en materia de información y documentación clínica. Spain,2002.

- Medeiros, R.M.K.; Figueiredo, G.; Correa, Á.C.P; Barbieri, M. Repercussions of using the birth plan in the parturition process. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2019;40,e20180233. [CrossRef]

- Mirghafourvand, M.; Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi, S.; Ghanbari-Homayi, S.; Jahangiry, L.; Nahaee, J.; Hadian,T. Effect of birth plans on childbirth experience: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019, 25, e12722. [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.H.; Muggleton, S.; Davis, D.L. Birth plans: A systematic, integrative review into their purpose, process, and impact. Midwifery. 2022, 111, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, B.; Doroszewska, A.; Kubicka-Kraszyńska, U.; Pietrusiewicz, J.; Adamska-Sala, I.; Kajdy, A.; Sys, D.; Tataj-Puzyna, U.; Bączek, G.; Crowther, S. Is there respectful maternity care in Poland? Women's views about care during labor and birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019, 19, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazy-Nancy, E.; Mattern, C.; Rakotonandrasana, B.I.; Ravololomihanta, V.; Norolalao, P.; Kapesa, L. A qualitative analysis of obstetric violence in rural Madagascar. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galera-Barbero, T.M.; Aguilera-Manrique, G. Women's reasons and motivations around planning a home birth with a qualified midwife in Spain. J Adv Nurs. 2022, 78, 2608–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Expert 1 |

Expert 2 |

Expert 3 |

Expert 4 |

Expert 5 |

Expert 6 |

Expert 7 |

Expert 8 |

CVI-i[CI95%]* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.92 [0.74-0.98] |

| Item 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.71 [0.51-0.85] |

| Item 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.79 [0.60-0.91] |

| Item 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.83 [0.64-0.93] |

| Item 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.88 [0.69-0.96] |

| Item 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.00 [0.86-1.00] |

| Item 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.79 [0.60-0.91] |

| Item 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.83 [0.74-0.93] |

| Item 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.88 [0.69-0.96] |

| Item 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.83 [0.64-0.93] |

| Item 11 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.92 [0.74-0.98] |

| Item 12 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0.75 [0.55-0.88] |

| Item 13 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.75[0.55-0.88] |

| Item 14 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.88[0.69-0.96] |

| Item | M [CI95%]* |

SD** | Symmetry*** | Kurtosis*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Members of the healthcare staff made ironic or derogative comments or made jokes about your behavior. | 1.22 [1.09-1.36] |

0.85 | 3.90 | 13.91 |

| 2- You were addressed to with nicknames or diminutives (e.g., mummy, chubby, etc.) or treated as if you were unable to understand the processes you were going through. | 1.10 [1.02-1.19] |

0.55 | 5.90 | 35.06 |

| 3- You felt treated as a child or neglected by the staff, as if you were unable to make decisions about what was happening to you before, during or after delivery. | 1.25 [1.13-1.39] |

0.82 | 3.55 | 12.11 |

| 4- You were somehow criticized for expressing your emotions (cry, scream of pain, etc.) during labor or delivery. | 1.24 [1.10-1.38] |

0.86 | 3.70 | 12.54 |

| 5- It was impossible for you to ask queries or express your fears or concerns because nobody answered, or they answered in a bad way. | 1.18 [1.07-1.31] |

0.74 | 4.34 | 18.20 |

| 6- You were subjected to medical procedures without asking your consent or without explaining why such procedures were needed. | 1.37 [1.21-1.54] |

1.03 | 2.79 | 6.47 |

| 7- At the moment of delivery, you were compelled to keep lying on your back despite you expressed you discomfort with that position. | 1.27 [1.13-1.42] |

0.90 | 3.32 | 9.83 |

| 8- You were compelled to stay in bed and prevented from walking or seeking the position you needed. | 1.21 [1.09-1.35] |

0.79 | 3.88 | 14.26 |

| 9- You were not allowed to be accompanied by someone you trusted in. | 1.15 [1.04-1.27] |

0.71 | 4.75 | 21.46 |

| 10- You were prevented from having immediate contact with your newborn, before the doctor took him/her away (caressing, holding him/her in your arms, etc.). | 1.21 [1.09-1.35] |

0.83 | 3.83 | 13.36 |

| 11- After delivery, they make you feel you had not behaved up to what was expected of you (that you had not "helped"). | 1.08 [1.00-1.16] |

0.48 | 6.55 | 44.21 |

| 12- Your childbirth care experience made you feel vulnerable, guilty or insecure in any sense. | 1.23 [1.11-1.37] |

0.80 | 3.59 | 12.22 |

| 13- After delivery, you were denied the opportunity to use a birth control device or procedure (IUD, tubal ligation, etc.). | 1.09 [1.01-1.17] |

0.50 | 6.17 | 39.37 |

| 14- During or after labor, you felt exposed to the gaze of other people unknown to you (exposure to strangers). | 1.46 [1.28-1.65] |

1.16 | 2.41 | 4.24 |

| Items | Factor 1 | IC95%* |

| 1- Members of the healthcare staff made ironic or derogative comments or made jokes about your behavior. | 0.721 | [0.354-0.878] |

| 2- You were addressed to with nicknames or diminutives (e.g., mummy, chubby, etc.) or treated as if you were unable to understand the processes you were going through. | 0.645 | [0.299-0.892] |

| 3- You felt treated as a child or neglected by the staff, as if you were unable to make decisions about what was happening to you before, during or after delivery. | 0.842 | [0.594-0.963] |

| 4- You were somehow criticized for expressing your emotions (cry, scream of pain, etc.) during labor or delivery. | 0.748 | [0.387-0.912] |

| 5- It was impossible for you to ask queries or express your fears or concerns because nobody answered, or they answered in a bad way. | 0.884 | [0.470-1.000] |

| 6- You were subjected to medical procedures without asking your consent or without explaining why such procedures were needed. | 0.745 | [0.364-0.868] |

| 7- At the moment of delivery, you were compelled to keep lying on your back despite you expressed you discomfort with that position. | 0.486 | [0.188-0.739] |

| 8- You were compelled to stay in bed and prevented from walking or seeking the position you needed. | 0.790 | [0.377-0.918] |

| 9- You were not allowed to be accompanied by someone you trusted in. | 0.695 | [0.334-0.898] |

| 10- You were prevented from having immediate contact with your newborn, before the doctor took him/her away (caressing, holding him/her in your arms, etc.). | 0.771 | [0.375-0.911] |

| 11- After delivery, they make you feel you had not behaved up to what was expected of you (that you had not "helped"). | 0.891 | [0.491-1.000] |

| 12- Your childbirth care experience made you feel vulnerable, guilty or insecure in any sense. | 0.957 | [0.734-1.000] |

| 13- After delivery, you were denied the opportunity to use a birth control device or procedure (IUD, tubal ligation, etc.). | 0.473 | [-0.489-0.764] |

| 14- During or after labor, you felt exposed to the gaze of other people unknown to you (exposure to strangers). | 0.755 | [0.460-0.949] |

| Item | Difficulty Index* | Infit-WMS** | Outfit-UMS** |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Members of the healthcare staff made ironic or derogative comments or made jokes about your behavior. | -0.09 | 1.09 | 1.17 |

| 3-You felt treated as a child or neglected by the staff, as if you were unable to make decisions about what was happening to you before, during or after delivery. | -0.08 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| 4-You were somehow criticized for expressing your emotions (cry, scream of pain, etc.) during labor or delivery. | -0.11 | 1.18 | 1.39 |

| 5-It was impossible for you to ask queries or express your fears or concerns because nobody answered, or they answered in a bad way. | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.58 |

| 6-You were subjected to medical procedures without asking your consent or without explaining why such procedures were needed. | -0.32 | 1.08 | 1.06 |

| 7-At the moment of delivery, you were compelled to keep lying on your back despite you expressed you discomfort with that position. | -0.11 | 1.06 | 1.08 |

| 8-You were compelled to stay in bed and prevented from walking or seeking the position you needed. | -0.00 | 0.93 | 0.76 |

| 9-You were not allowed to be accompanied by someone you trusted in. | 0.10 | 1.16 | 1.16 |

| 10-You were prevented from having immediate contact with your newborn, before the doctor took him/her away (caressing, holding him/her in your arms, etc.). | -0.03 | 1.02 | 0.95 |

| 11-After delivery, they make you feel you had not behaved up to what was expected of you (that you had not "helped"). | 0.54 | 0.86 | 0.37 |

| 12-Your childbirth care experience made you feel vulnerable, guilty or insecure in any sense. | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.45 |

| 13-After delivery, you were denied the opportunity to use a birth control device or procedure (IUD, tubal ligation, etc.). | 0.53 | 1.09 | 1.13 |

| 14-During or after labor, you felt exposed to the gaze of other people unknown to you (exposure to strangers). | -0.46 | 1.21 | 1.17 |

| Variables | M(SD)* | p-value** | Effect size*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | |||

| Primiparous (n=159) | 3.59 (7.39) |

0.040** |

0.23 |

| Multiparous (n=97) | 2.11 (4.75) | ||

| Episiotomy | |||

| No (n=224) | 2.63 (5.97) |

0.012** |

0.50 |

| Yes (n=32) | 5.84 (9.32) | ||

| You were asked consent for episiotomy | |||

| No (n=15) | 8.93 (9.87) |

0.010** |

0.65 |

| Yes (n=17) | 3.12 (8.13) | ||

| Artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) | |||

| No (n=173) | 2.38 (6.43) |

≤0.001** |

0.31 |

| Yes (n=83) | 4.40 (6.62) | ||

| You were asked consent for ARM | |||

| No (n=18) | 9.78 (7.26) |

≤0.001** |

1.14 |

| Yes (n=65) | 2.91 (5.63) | ||

| Inducing labor | |||

| No (n=140) | 2.81 (6.80) |

0.195 |

0.07 |

| Yes (n=116) | 3.29 (6.24) | ||

| You were asked consent for inducing labor | |||

| No (n=18) | 6.83 (7.23) |

≤0.001** |

0.68 |

| Yes (n=99) | 2.70 (5.85) | ||

| Prohibition of receiving food | |||

| No (n=192) | 2.74 (6.52) |

0.018** |

0.18 |

| Yes (n=64) | 3.89 (6.61) | ||

| Epidural analgesia | |||

| No (n=70) | 1.56 (3.84) |

0.006** |

0.31 |

| Yes (n=186) | 3.59 (7.24) | ||

| Presentation of a childbirth plan | |||

| No (n=182) | 2.40 (5.75) |

0.066 |

0.34 |

| Yes (n=74) | 4.58 (8.03) | ||

| Your childbirth plan was observed | |||

| No (n=12) | 12.42 (12.93) |

≤0.001** |

1.28 |

| Yes (n=62) | 3.04 (5.70) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).