1. Introduction

Massification in higher education has made the satisfaction of students’ needs a difficult conundrum among university lecturers. Over the past 5 years, there has been an increase in the intake of students in the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture; Department of Science Foundation Programme at the University of Venda. The trend has seen an increase from 150 student intakes to 200 intakes per annum since the 2019 academic year. High enrolments within a specific course led to different students’ appetites brought by students’ dimensions of differences. Generally, massification leaves institutions of higher learning with an increased number of enrolments of diverse students from all walks of life to learning and teaching activities that are set out through a single set of curricula. This sets out a one-size-fits-all approach to learning and teaching activities which poses shortcomings in students’ mastery of concepts within the curriculum. In addressing this shortcoming, a traditional learning approach that is teacher-centered is likely not to address students’ appetite in and off the classroom. Biggs (2012); Biggs (1999) alluded that learning-related activities within any prescribed curriculum should stimulate the academic focus and zeal for learning of the students, as they jointly affect students’ levels of engagement in each task. Although the curriculum is one-size-fits-all, learning and teaching activities within such a curriculum should lead students to mastery either through individual or collaborative learning. In contrast, the use of innovative design for collaborative learning enhances student engagement in the populous student’s context. Moreover, this paper aims to extensively explore innovative designs for fostering student engagement and collaborative learning among first-year students at the University of Venda.

2. Literature Review

Oliveira et al (2022) argued that several studies that have been done on gamification indicated that most studies only consider students’ gamer types to tailor the systems, yet not providing sufficient statistical and empirical evidence, on students learning and performance using gamified systems in the curriculum. Oliveria et al (2022) highlighted that most empirical studies in gamification findings were as follows:

- (i)

Gamification aims to improve students’ concentration, engagement, performance, and/or decrease students’ frustration and demotivation in educational systems (Cozar-Gutierrez & Saez-Lopez, 2016; Shi & Cristea, 2016; Lopes et al., 2019; Metwally et al., 2020);

- (ii)

gamification can offer different ways for students to perform desired educational activities associated with game elements (Majuri et al., 2018; Koivisto & Hamari, 2019; Bai et al., 2020);

- (iii)

gamification yields benefit to students, e.g., increasing students’ motivation, enhancing learning performance, or improving training processes (Kapp, 2012; Larson, 2020; Shi et al., 2014; Cozar-Gutierrez & Saez-Lopez, 2016; Stuart et al., 2020; Lo & Hew, 2020; Zainuddin et al., 2020).

Several studies highlight the importance of gamification to aid students’ performance and enhance mastery of the taught concepts within the curriculum. Toda et al., (2017); Koivisto and Hamari, (2019) agreed that gamification in an educational context does not necessarily improve student outcomes. Nevertheless, it is generally expected that gamification may help students towards some highly dense mastery of the concepts being taught. Generally, various students' and teachers’ tastes on gamification concepts may differ, with some teachers and students not subscribing to gamification as part of their learning and teaching activities but rather prefer traditional learning and teaching. Moreover, there are some students and teachers who may find gamification to be helpful in the quest to master threshold concepts. However, it is upon teaching practitioners to help each student individually or collectively in aiding them towards understanding critical curriculum concepts either using the traditional methods or innovative methods such as gamification in their learning and teaching roll-out. Therefore, it is critical to highlight that amid the use of gamification and collaborative learning, students’ satisfaction is likely not going to be holistically achieved. Students’ taste in learning varies and this is brought about by their dimension of differences.

Giannakis and Bullivant (2016) as argued by Hornsby and Osman (2014), stressed that the global increase in student enrolment in higher education qualifications may imply an inverse relationship with higher education service quality. This notion was also stressed by several researchers (McKeachie 1980; Cooper and Robinson, 2000; Ehrenberg et al. 2001; Cuseo, 2007; Mulryan-Kyne 2010 and Hornsby and Osman, 2014). The contrast is that there is a general norm of belief that the number of students in a class has a correlation with learning and teaching quality and performance. Giannakis and Bullivant (2016) argued that massification affects the service quality of learning and teaching activities in higher education. Although class size is not the only determinant of students’ performance, class size matter in the delivery and experiences of learning and teaching to the overall participants in a classroom (McKeachie 1980).

Our foundation programme massification grew from 150 to 200 students since 2019, thus an increase in enrolment of 33,33%. The enrolments have some impacts on learning and teaching deliverables as well as students’ experiences on the learning and teaching activities. In addressing challenges posed by increased enrolments threatening the quality of education, this study explored innovative designs for fostering student engagement and collaborative learning. This is a learning and teaching activity in a curriculum that sought to address students’ dimensions of differences within collaborative learning by demonstrating their understanding of certain content in the module via given class tasks, assessments, and/or assignments.

2.1. Game-based Learning and Gamification

In an education context, game-based, gamification and collaborative learning are used to improve students focus on learning, engagement with learning activities facilitated by their peers or teachers, and performance, as well as to alleviate students’ frustration and demotivation in teaching and learning (Oliveira, et al, 2023). Tan Ai Lin, Ganapathy and Kaur (2018) highlighted that both game-based learning and gamification should be used in a manner that allows learners the opportunity to be fully involved in the learning activities. They further argued that this kind of student-focused engagement aids learners’ full concentration and mastery of concepts due to its ‘play nature’. In our context, we used students’ collaborative learning in fostering engagement, attention, and promotion of knowledge whilst they do their assigned activity.

Wiggins (2016) differentiated between game-based and gamification learning: (i) game-based learning which is the use of actual games in the learning and teaching context to enhance students’ mastery, (ii) gamification is the use of game-design elements in a non-game context. This study was solely focusing on gamification and collaborative learning and not on game-based design and methodologies pertaining to game-based learning. Zicherman (2011) and Kapp (2012) highlighted that gamification is a process in which people make use of the thinking and mechanics behind games for problem-solving and audience engagement. This study focused on the use of gamification to enhance and foster student engagement and collaborative learning. Students used their artistic and game aesthetics abilities to write up and present their assignments. A hidden curriculum in this activity was that students were learning through social constructivism which led students into researching a particular concept, understand the concepts, and interpret it through gamification.

2.2. Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning is an educational approach to students’ interaction in learning and teaching that happens within peers or groups of learners working together to solve a given problem, task completion, or in creating a product (Laal and Ghodsi, 2012). Oxford (1997) asserted that collaborative learning has a "social constructivist" philosophical base, which views learning as the construction of knowledge within a social context and therefore encourages the acculturation of individuals into a learning community. In this phenomenon, collaborative learning is achieved through interaction and knowledge construction among the learners and the teacher. In this philosophy of learning, learners are seen and perceived as knowledge communities. This means that learners are core creators of knowledge simultaneously with the teacher. This is achieved through social constructivism amongst the learners in creating, sharing, and adding to knowledge construction with the “more capable others”.

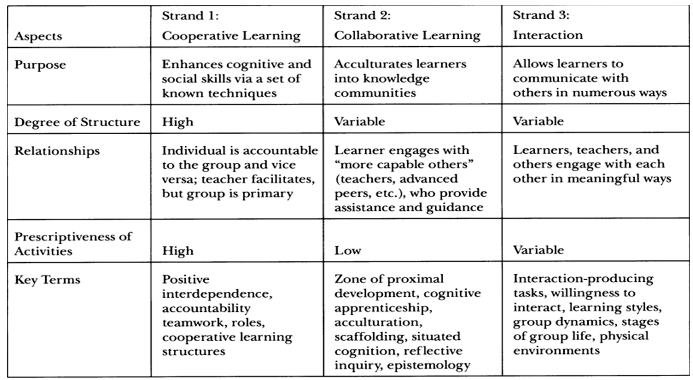

This is a distinct difference between cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and interaction highlighted by Oxford (1997).

Table 1 below expands on the differences.

This study’s objective is to explore innovative and creative strategies for fostering students’ engagement and collaborative learning. The collaborative learning philosophy was explored wherein students worked in groups to create and constructing knowledge amongst themselves and with the “more capable others”.

2.3. Theoretical Framework

Vincent Tinto (2003, 2017a) as the proponent of the social integration theory argues that students ‘perceptions of their social integration into the institution represent an important factor in their persistence. This means that students who feel connected to their peers and feel satisfied with their educational experience tend to persist. Students who feel isolated or unsupported by their peers and faculty or who do not feel engaged in the life of the institution are more likely to drop out. In line with this study, the innovative and creative designs were integrated through collaborative learning where students were assigned tasks to work in groups. Moreover, the students could use their talents to express their conceptualisation of key concepts and course content through presentations. This social engagement may enable the students to feel connected to the learning environment and more satisfied with the experience through peer-to-peer feedback helping them feel less isolated as students.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study design

This study employed a purposeful sampling research approach on selected students enrolled for Foundation Biology 1140 (FBI 1140) and Foundation English Skills (FGS 1140) at the University of Venda. The study is based on a collaborative design that aims to explore the effects of project-based learning focusing on students’ different talents to promote their mastery of Biology content and English-speaking skills. Students were first pre-tested to evaluate their language-speaking skills and biology content knowledge. For the data collection, students were first asked to identify their various talents to execute the projects. In the second step, students were provided with different topics related to Biology. In addition, they were given a period of seven weeks to work on their various projects. Subsequently, students were post-tested on their collaborative participation skills after they were finished with their various projects. Consequently, interviews were conducted to reflect on students’ perceptions of the use of collaborative projects to understand certain content of the selected foundational modules.

3.2. Different stages of the projects

The current projects consist of three steps which are 1) the planning stage, 2) the implementation stage, and 3) the creation of the product (Fried-Booth, 2002). The initial step is about planning, and it requires discussions between students and lecturers regarding the scope and content of the project (Sirisrimangkorn, 2018). Primarily, the purpose of the study was clearly outlined before the commencement of the project (Sirisrimangkorn, 2018). Four different talents: talk shows, poetry, singing, and drama were identified for the project. The second step was the implementation phase which assisted students to work on their different tasks for the projects. In this case, lecturers were available to provide guidance in times when challenges arose, support and monitor the progress to enhance students learning. At this stage, projects were structured to accommodate the exploration of the topics through various tasks which include script writing, songwriting, poem writing, information compiling, and a series of rehearsals. Moreover, the lecturers assisted students with challenges, for example, the lecturers intervened whenever the students could not reach a consensus or when the students required more clarity on aspects of the projects.

To conclude the projects, students were granted opportunities to perform their projects in approximately 25 minutes. Students’ performances took place in the presence of the lecturers and peers. Conveyance of academic content understanding through various talents is beneficial to students in a variety of ways: English speaking skills reinforcement, self-confidence development or improvement, and mastery of the content (Maley and Duff, 2006). Furthermore, feedback based on proper usage of the English spoken language, improper usage of the English spoken language, and mastery of the biology content was provisioned.

3.3. Research tools

The results of this study emerged from the utilisation of two instruments: participation observation (wherein the spoken English of participants was evaluated) and narrative inquiry (wherein semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain the students’ perceptions on the directives of the project-based learning focusing basically on singing, poetry, talk shows and drama to promote their vocabulary and mastery biological content (Sirisrimangkorn, 2018).

3.4. Data analysis

The descriptive analytical approach was used to analyse students’ reflections. In this case, the descriptive analysis includes frequencies and percentages of students’ responses. Microsoft Excel 5.0/95 was used to generate the graphical interpretation of the gathered information.

3.5. Ethical considerations

Explicit explanations of the purpose, objectives, and significance of the project guided all the students enrolled in the two foundational modules to participate in this survey. In this study, ethical approval was not required as the participants were students enrolled in the course. Moreover, informed consent was sought prior to students’ participation in this study. Therefore, participation in this study was voluntary and students were at liberty to withdraw from the research at any time without any direct or indirect implication to the study or their enrolled course.

4. Results

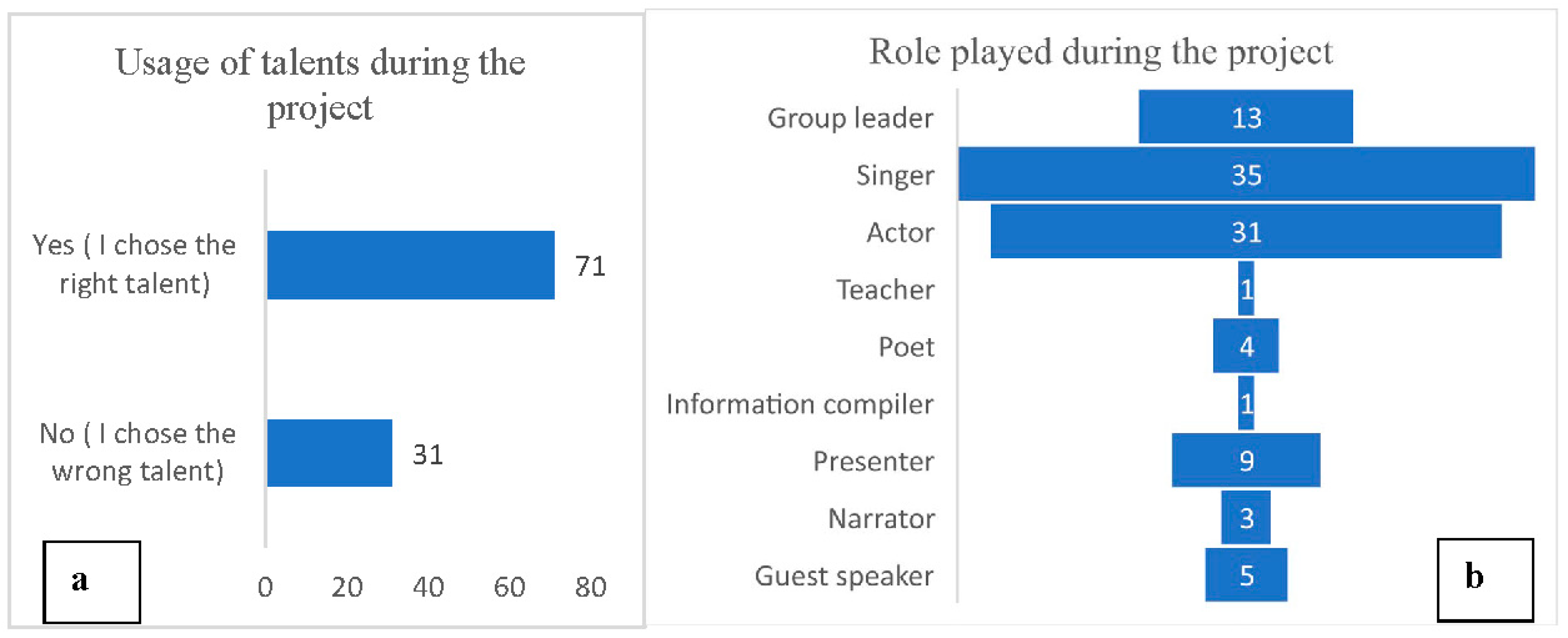

The findings of this study emerged from the four different talents used to explore innovative and creative strategies for fostering student engagement and collaborative learning. A total of ten questions about students’ perceptions were evaluated to explore the benefits of project-based learning. Students used different talents to execute the project. A total of 71 students chose the appropriate talents whereas 31 students indicated the inappropriate choice of talents due to the lack of space within those groups (

Figure 1a). To expedite different talents, students played 9 distinct roles that could be interchangeably within each group amid their presentation. There was no static order on how each group and students were supposed to present their talent. It was within each group's discretion to choose which talent they were going to employ to execute the project. Amongst the chosen talents, singing and acting roles were most preferred by most students and groups (

Figure 1b).

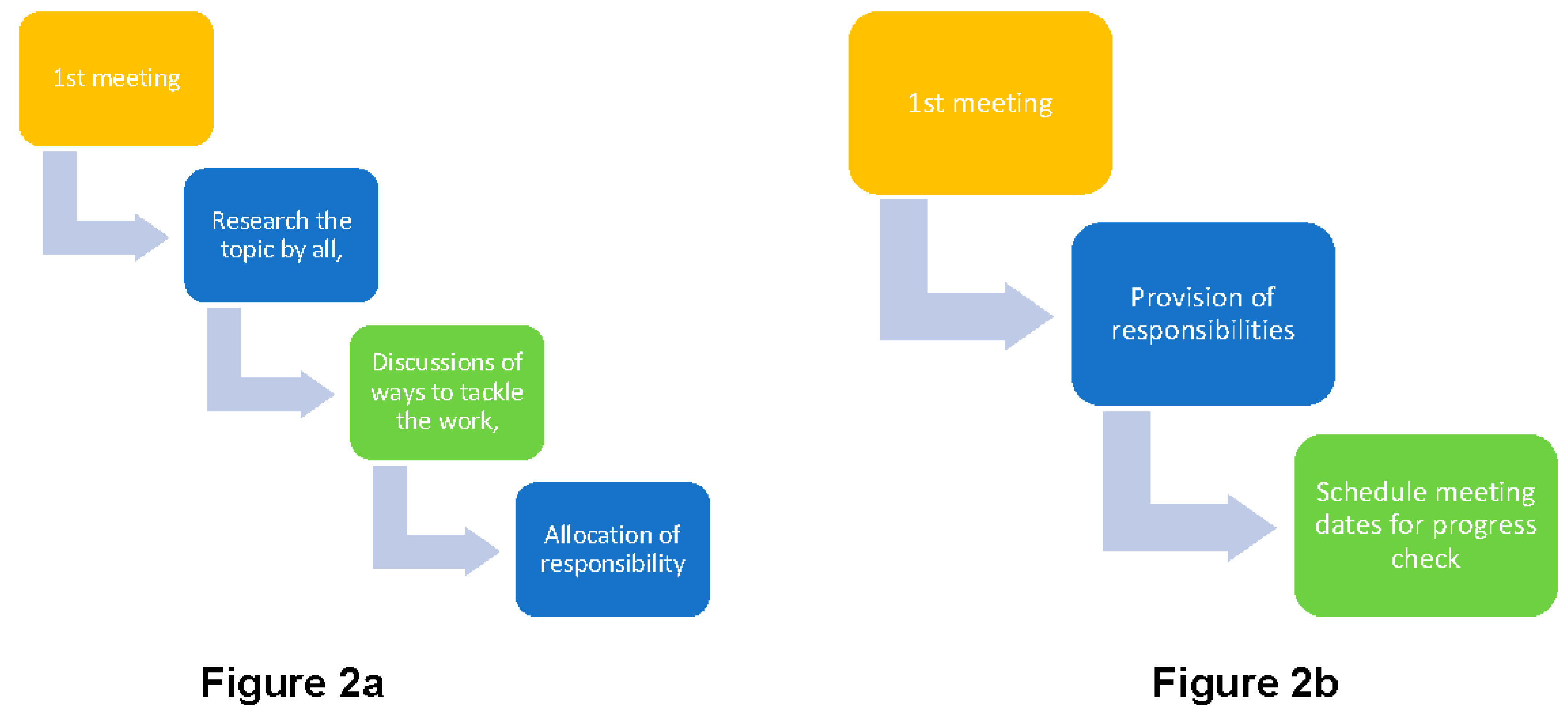

During the planning phase of the projects, students followed two approaches wherein 78 students used a 4-way approach, and 27 students used a 3-way approach (

Figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 2a and 2b above shows the approaches followed by students when allocating different tasks to each group member to aid and ease the execution of the project. Although the allocation of tasks as per

Figure 2a and 2b slightly differs, most students opted to make extensive research on the biology concepts embodied in the project. Thereafter, presentation formalities and responsible individuals were allocated to individuals within the group. Moreover,

Figure 2b shows that some students and groups allocated responsibilities as soon as their initial meeting, thereafter, followed by a scheduled meeting purposed to check the group's progress through individual tasks allocated.

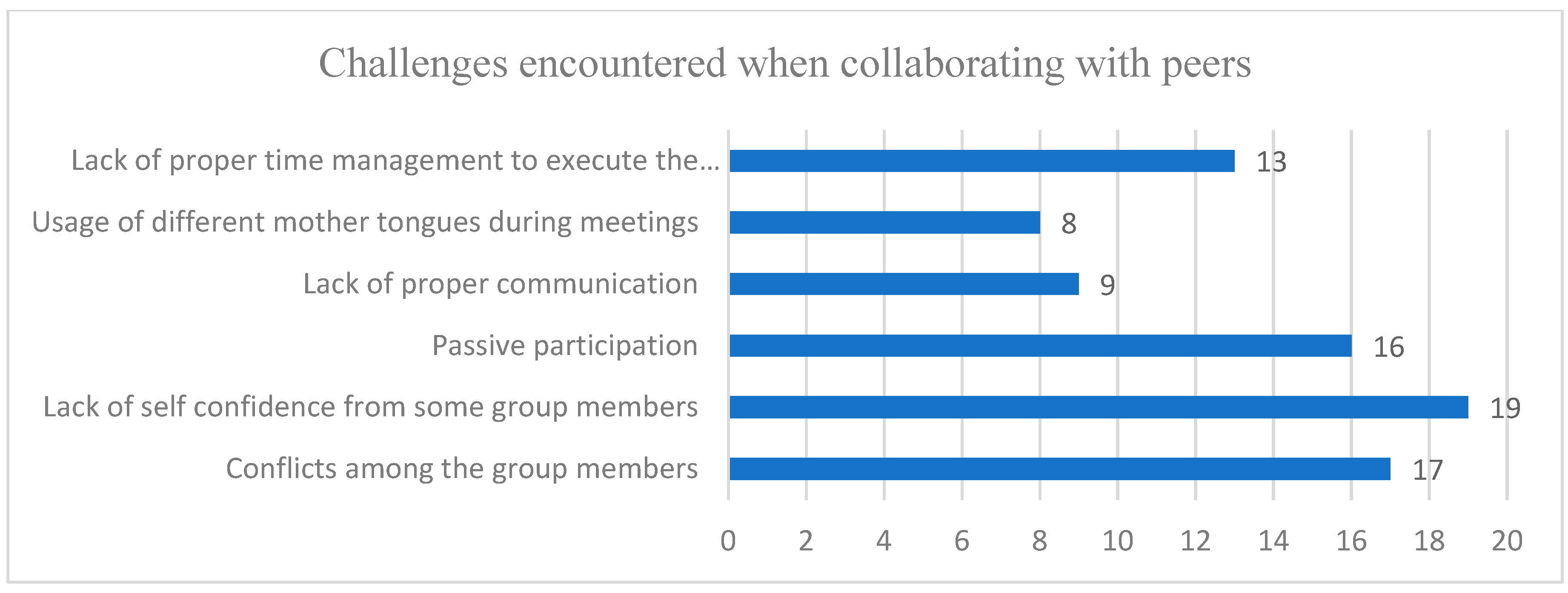

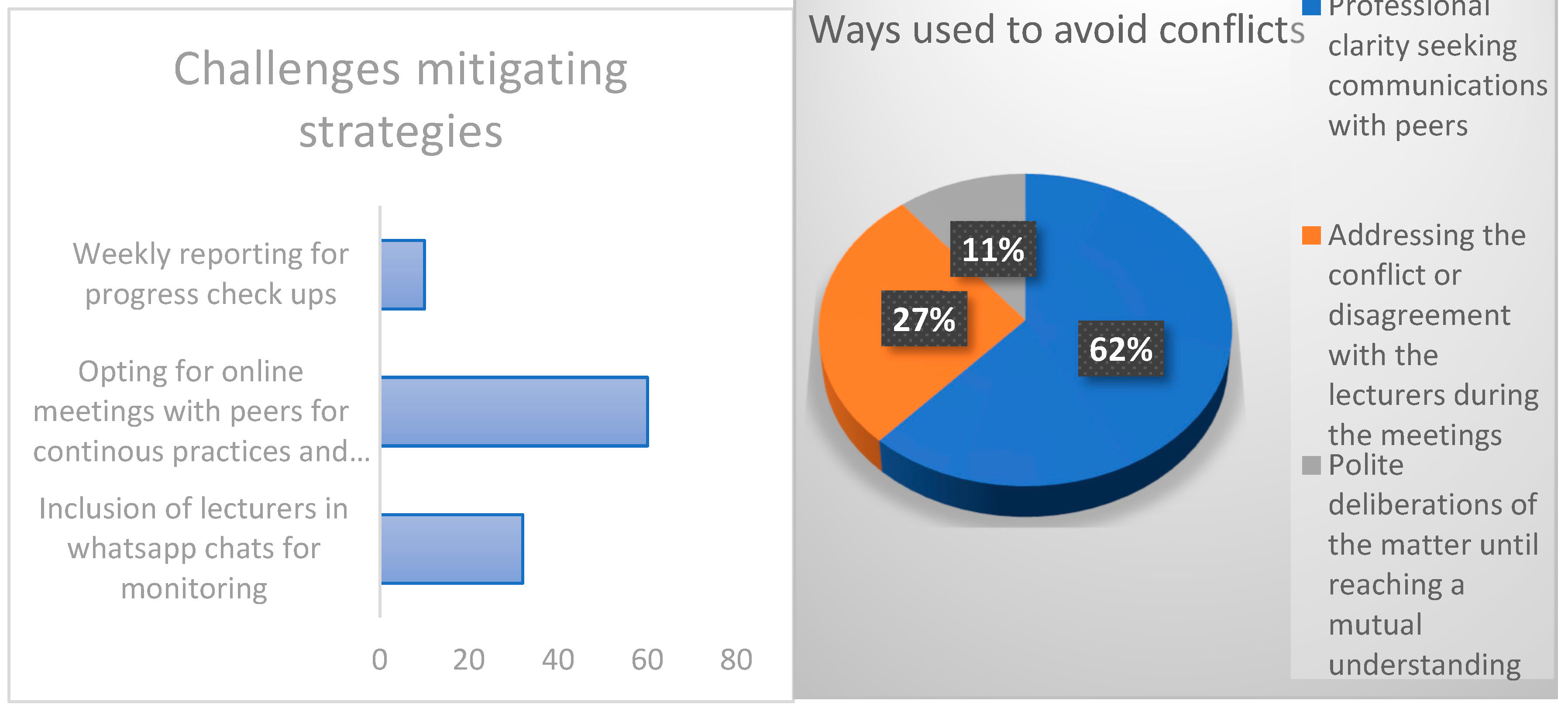

Implementation of collaborative learning or project-based learning has some challenging aspects especially when the interaction is between peers. Various challenges attested from the activity include lack of self-confidence from some of the group members, conflicts among the group members, passive participation, lack of proper time management to execute the project, and lack of proper communication and usage of different mother tongues during planning or progress check meetings (

Figure 3). Nevertheless, three meditative mitigation strategies were put in place to promote a cooperative spirit (

Figure 4a) and additional ways were adopted to avoid conflicts (

Figure 4b).

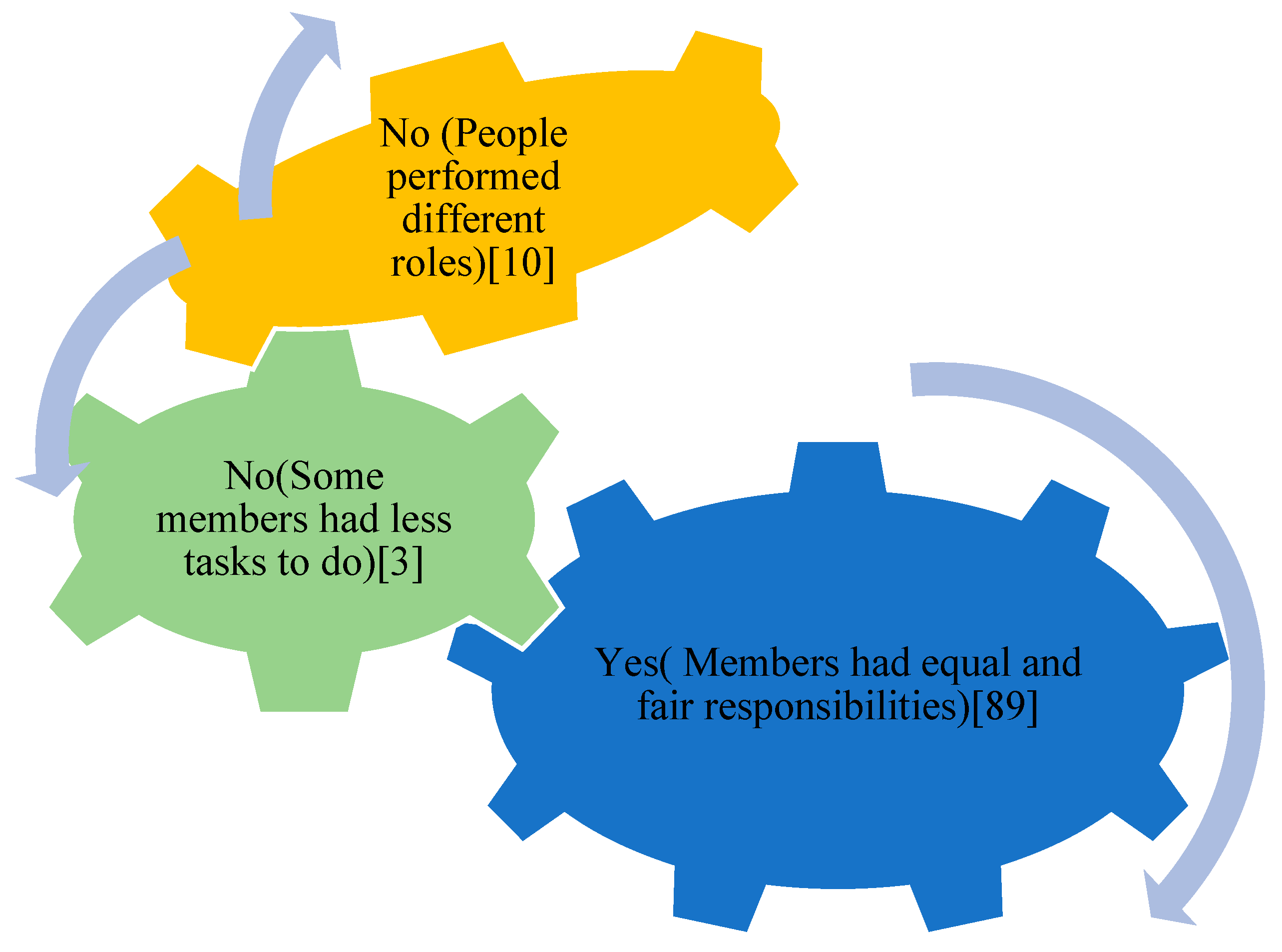

It was apparent that students used their potential to perform various roles toward the completion of the projects. The results of this study indicated that a total of 89 students felt that members had equal and fair responsibilities to execute within their groups. On the other hand, 10 students attested that the responsibilities were not the same since group members performed different roles. On the contrary, only 3 students stated that some were reasonably given fewer responsibilities whereas some were tasked with a high workload toward the completion of the projects (

Figure 5).

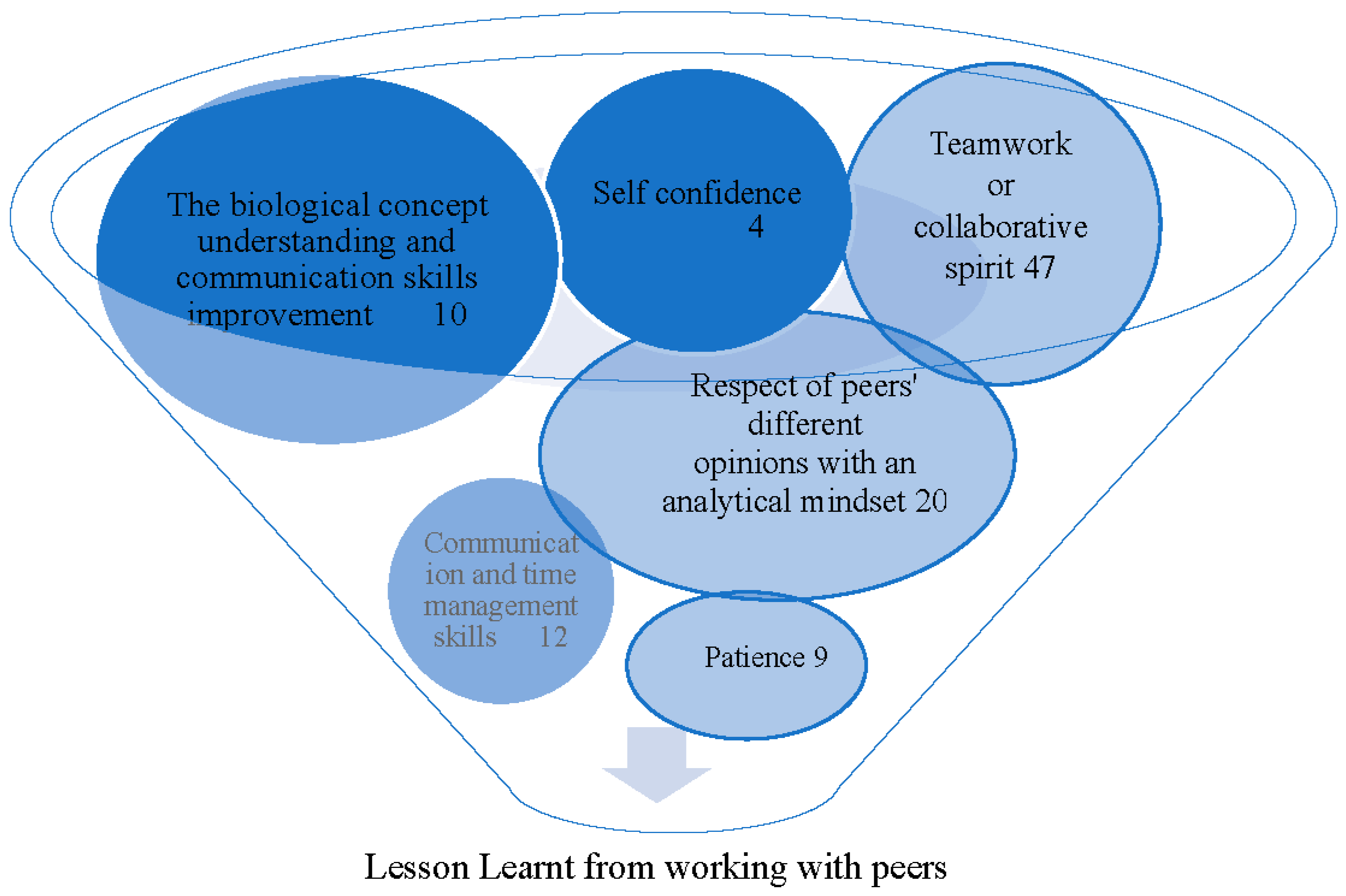

Based on the results, students mentioned the development of collaborative skills, respect for peers’ different opinions with an analytical mindset, communication, and management skills. Some students benefited from the overall activity by gaining a better understanding of the biological sciences concepts (

Figure 6).

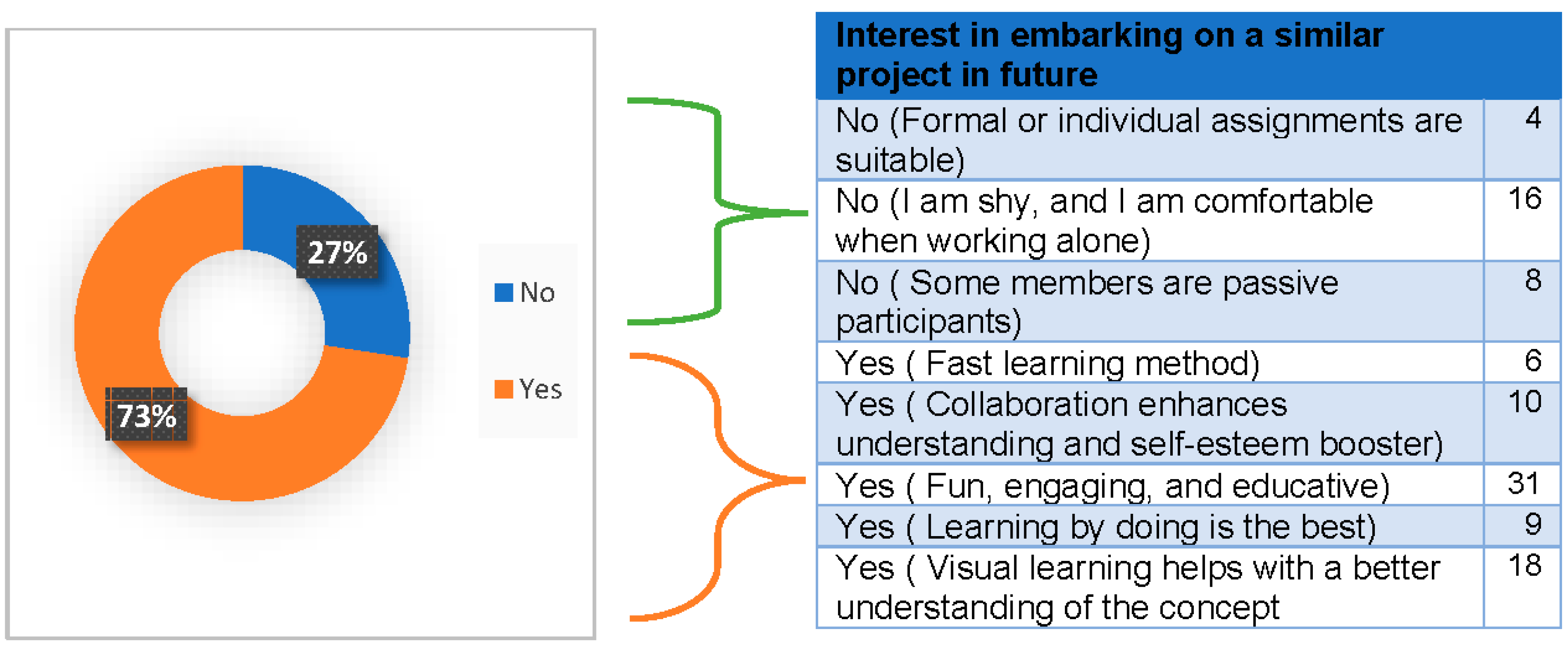

Essentially, the highest percentage of 73% showed interest in embarking on a similar project because they found it to be a fast-learning method, collaboration enhancer, and self-esteem booster. Some students elucidate that they had fun, and moreover found the activity to be more engaging and educative. A reasonable number of students indicated the significance of learning by doing which increasingly instilled a better understanding of the biological content knowledge, furthermore, enhancement of their communication skills. Opposingly, some students (n=28) are not in concurrence with previous testimonies as they felt pressurised when collaborating with passive team members and as such, they prefer formal or individual assignments. On the same note, some students from this category mentioned that they are shy and therefore prefer to work alone (

Figure 7).

5. Discussion

The collaborative learning space should inspire or propel students socially, mentally, emotionally, and intellectually depending on student type and motivation to learn.

5.1. Challenges encountered when collaborating with peers

The findings of this study report conflict among the group members during the collaborative projects. The lack of self-confidence from some group members has been observed as a critical concern in various groups working on the task collaboratively. The students were not confident to play their roles on the stage prior to the actual performance of the task. The usage of different mother tongues during the meeting wherein Tshivenda, Tsonga, or Sepedi became the dominant medium of communication tended to disadvantage the speakers of other languages who could not understand the major points of discussion. The studies in retrospect are in congruence with this study by Koivisto and Hamari (2019) argued that linguiça franca exacerbates disagreement among the students. This shortcoming has been reported by the study of Hornsby and Osman (2014) which articulate that collaborative learning usually has conflicting ideas among the students which turns into argumentation in certain aspects of what is correct and what is not. On the contrary, passive participation in some groups was a major conundrum for the group leaders to monitor and evaluate the individual member’s progress.

5.2. Students ‘interests in embarking on similar projects in the future

The report indicated that 73% of the students are comfortable in executing this project in the future while 27% of the students feel uncomfortable embarking on this project owing to the notion that their group members are passive and reluctant to participate in their assigned tasks. Moreover, the students reported that collaborative projects are a fast and quick method for learning and knowledge acquisition. The students indicated that collaborative learning enhances their understanding of complex and tricky course content. Significantly, learning by doing is the best as they were afforded the opportunity to use their talents to unleash untapped potential (Biggs, 2012). This is congruent with the study of Laal and Ghodisi (2012), who articulated that collaborative learning is quite beneficial in the co-construction of knowledge and finding deeper meaning in concepts through different viewpoints. Significantly, the students were hugely interested in participating in similar projects.

5.3. The role played during the project.

Some students took as the group leaders in their respective teams to monitor and evaluate the progress of each member. Other students were expected to demonstrate their understanding of the content and concepts of the subject through music wherein the students played the role of Singers. This study is consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Oliveira et al (2023) which bring about the use of active learning such as debates, role-plays, experiments, or simulations to make the learning experience more engaging. Subsequently, the students were afforded an opportunity to be actors and actresses. In congruence with the findings of the study by Stuart et al (2020) articulated that this can help students connect with the content on a deeper level. Fundamentally, the other groups opted to be Poets to use poetic devices and diction to strategically incorporate their skills and talents. Moreover, it shows forth the understanding of the content knowledge and practical application of some concepts in different contexts.

Consequently, the role-plays contribute prolifically to the student’s learning and understanding of the concepts of the course in their assigned tasks which encompass; Information Compiler, Presenter, Narrator, Guest Speaker, and so forth to create a meaningful learning experience. This study is validated by the findings of a study conducted by Mulryan-Kyne (2010) which indicated and suggested a dynamic approach to establishing student involvement in the ongoing lesson.

5.4. Usage of talents during the project

The seventy-one (71) students indicated that they used their talents effectively in executing the project. This resonates with the study conducted by. The thirty-one (31) students reported that they used their talents unsatisfactorily. This study is consistent with the study by Majurin et al (2018), who elucidate that the use of talents among the students enables them to have a sense of belonging in the institution through social engagement with their peers. Furthermore, the students were satisfied with the unprecedented experience of having social engagement in their mastery of difficult concepts of English and Biology. This is consistent with Mokganya and Zitha’s (2023) intervention strategies for leveraging the students’ knowledge regardless of their educational backgrounds. This is to ensure that the decontextualisation among students from homogeneous backgrounds is possibly mitigated. Moreover, this further strengthens engagement with students by enabling the students to make deeper connections with those who have similar talents. Integrating talents into lessons can make them more creative, and innovative and expedite the mastery of the content knowledge.

5.5. Approaches followed by the students when allocating different tasks for the execution of the project.

The approaches employed by the students were to allocate different sections of the research topic to all members to expedite the completion of the project and to each student conducting research on their specific allocated section(s). This study is validated by Shi and Crist (2016) 's findings on the techniques employed by the students in their cooperative learning or group discussion to complete the project. The students scheduled meeting dates for the inspection of progress among the group members. The approaches afforded the students could not understand the task to grasp the notion of the task (Tan Ai Lin et al, 2018). Furthermore, this encouraged the students to work together in an innovative way through collaborative learning this was to enforce thorough student engagement.

5.6. Distribution of responsibilities among the group members

The findings of the study elucidate that the students were assigned responsibilities among the group members. While the ten (10) students performed different roles. Three (3) students had fewer tasks to do. Consequently, eighty-nine (89) students had equal and fair responsibilities. Moreover, the students further reported that they were able to identify and monitor those who are either lazy or reluctant to work on their assigned tasks. This study is corroborated by the findings reported by Bai (2020) who stated that the distribution of roles among the students brings about effective learning. Based on the observation, this project ran smoothly as the group leaders in respective groups were constantly following up with the members who were not actively involved in the assigned task. In the same vein, the study of Kapp’s (2012) observation reported similar changes with respect to impediments to student participation.

5.7. Lessons learned from the collaborative project.

The findings of this paper reported that the students were impressed by this collaborative and creative learning and for some students, the project boosted self-confidence. This study is corroborated by the study which elucidated that the students tend to believe in themselves when their efforts and achievements. Teamwork or collaborative spirit. Effective communication and time management skills. Patience. Respect for peers’ different viewpoints with an analytical mindset. Some studies are in support of the findings that this type of project enables students to understand the significance of peer-to-peer learning and group work (Shi & Cristea, 2016).

Significantly, Giannakis and Bullivant (2016) stressed that when students are comfortable and at ease with their learning and teaching methods, they are more likely to demonstrate the best quality of work. This is achieved via a collaborative engagement of innovative learning where students discussed, shared, and presented their ideas openly and freely whilst others constructively gave some insights for improvement and the betterment of the project. Suggestions and inputs are more informed by their personal experiences, research, and mastery of concepts during the project write-up. As such, in agreement with Giannakis and Bullivant (2016) the students, lecturers, teaching and learning approaches, and the desire to foster a positive classroom culture skewed to concept mastery are seminal ingredients in collaborative learning.

Moreover, when teaching in a classroom with various students' differences, students with greater attempts towards interaction, research, and collaboration make a noticeable difference in their written assignments in terms of content, mastery, and grades obtained. Through collaborative learning and gamification, the deployment of various forms of communication (discussions, presentations, debates, and write-ups) by students within the classroom and in their respective collaborative groups improves the quality of their final work and aids toward the development of topic, subtopics, and concepts mastered by each student within their groups. This approach of collaborative learning by students satisfies many important lecturer objectives, goals, and pacing of the syllabus leaving more time for learning and mastering some of the troublesome threshold concepts.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of innovative strategies inculcates harmonious involvement and active engagement among the students as they master the fundamental concepts and subject content through a collaborative learning strategy in place. In addition, the student-centered pedagogical approach and integration of talents, role-plays, and collaborative learning yielded positive results among the students in their learning and acquisition of subject concepts.

Conversely, collaborative learning and active learning are imperative in establishing a deep scholarship. Subsequently, they should be perceived as fundamental techniques to teaching in universities and colleges given the demands placed on students in the broader sense of life. It is establishing collaboration and fostering active learning can enhance many positive results in student performance and can usually be understood in a short period of time. It is imperative for lecturers to set the standard and pace for student engagement as expeditiously as possible in a class, bridge the student-lecturer divide, and empower students with a sense of agency over their own learning.

Since students share a common learning space, they should feel a sense of common engagement, a sense of harmonious involvement, and co-construction of knowledge instead of remote participation among their peers. Furthermore, the learning environment is a shared space as much as the activity that occurs in, it is a shared experience. As such, lecturer-led participation and teaching should be initiated and established in concurrence with this perception, connecting students as assets to uplift the essentiality of what is already occurring in the higher learning space.

7. Implications and Recommendations

The study has the following implications and recommendations that the lecturers should provide context and conditions where students can confidently learn among their peers. There is a need to incorporate technology tools, and multimedia resources to make the learning experience more interactive and visually appealing to the students. The lecturers should create a positive and inclusive classroom environment where students feel comfortable expressing their opinions, asking questions, and engaging in discussions. There should be room for building rapport with the students and creating a sense of belonging which can contribute to increased interest. The academics should encourage students to work together on projects, assignments as collaboration can foster engagement and provide opportunities for peer learning and support. The students should be provided with timely and constructive feedback on their work, highlighting their strengths and areas for improvement. Giving them a sense of ownership should be encouraged to ensure that the students increase their investment in the course.

References

- Bai, S, Hew, K F, & Huang, B 2020. Does gamification improve student learning outcomes? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J., 1999. What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher education research & development, 18(1), pp.57-75. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J., 2012. What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher education research & development, 31(1), pp.39-55. [CrossRef]

- Cuseo, J. 2007. The empirical case against large class size: Adverse effects on the teaching, learning, and retention of first-year students. Journal of Faculty Development, 21, 5–21.

- Ehrenberg, R. G., Brewer, D. J., Gamoran, A., & Willms, J. D., 2001. Class size and student achievement. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(1), 1–30.

- Giannakis, M. and Bullivant, N., 2016. The massification of higher education in the UK: Aspects of service quality. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(5), pp.630-648. [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, D.J. and Osman, R., 2014. Massification in higher education: large classes and student learning. Higher education, 67, pp.711-719. [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M., 2012. The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Koivisto, J, & Hamari, J., 2019. The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. [CrossRef]

- Laal, M. and Ghodsi, S.M., 2012. Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences, 31, pp.486-490.

- Larson, K., 2020. Serious games and gamification in the corporate training environment: A literature review. TechTrends, 64(2), 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Lo, C K, & Hew, K F 2020. A comparison of flipped learning with gamification, traditional learning, and online independent study: The effects on students’ mathematics achievement and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(4), 464–481. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V, Reinheimer, W, Bernardi, G, Medina, R, & Nunes, F B 2019. Adaptive gamification strategies for education: A systematic literature review. In Brazilian Symposium on computers in education, (Vol. 30 p. 1032).

- McKeachie, W. J. 1980. Class size, large classes, and multiple sections. Academe, 66(1), 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A H S, Yousef, A M F, & Yining, W. 2020. Micro design approach for gamifying students’ assignments. In 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (pp. 349–351). IEEE.

- Majuri, J, Koivisto, J, & Hamari, J 2018. Gamification of education and learning: A review of the empirical literature. In Proceedings of the 2nd international GamiFIN conference, GamiFIN 2018. CEUR-WS.

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. 2010. Teaching large classes at college and university level: Challenges and opportunities. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 175–185. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A.M., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P.T. and Isotani, S., 2023. Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), pp.373-406. [CrossRef]

- Oxford, R.L., 1997. Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and interaction: Three communicative strands in the language classroom. The modern language journal, 81(4), pp.443-456. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. and Cristea, A.I., 2016. Motivational gamification strategies rooted in self-determination theory for social adaptive e-learning. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems: 13th International Conference, ITS 2016, Zagreb, Croatia, June 7-10, 2016. Proceedings 13 (pp. 294-300). Springer International Publishing.

- Stuart, H, Lavoue, E, & Serna, A. 2020. To tailor or not to tailor gamification? An analysis of the impact of tailored game elements on learners’ behaviours and motivation. In 21st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (pp. 216–227).

- Tan Ai Lin, D., Ganapathy, M. and Kaur, M., 2018. Kahoot! It: Gamification in higher education. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 26(1).

- Wiggins, B.E., 2016. An overview and study on the use of games, simulations, and gamification in higher education. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 6(1), pp.18-29. [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z, Shujahat, M, Haruna, H, & Chu, S K W. 2020. The role of gamified e-quizzes on student learning and engagement: An interactive gamification solution for a formative assessment system. Computers & Education, 145, 103729. [CrossRef]

- Sirisrimangkorn, L. 2018. The use of project-based learning focusing on drama to promote speaking skills of EFL learners. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 9(6), 14-20. [CrossRef]

- Fried-Booth, D. L. 2002. Project work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maley, A. & Duff, A. 2006. Drama techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mokganya, G. and Zitha, I., 2023, February. Assessment of First-Year Students’ Prior Knowledge as a Pathway to Student Success: A Biology Based Case. In The Focus Conference (TFC 2022) (pp. 233-246). Atlantis Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).