Background of the study

In the contemporary world, unemployment is one of the primary concerns in both developed and underdeveloped nations. Youth, which the United Nations describes as those between the ages of 15-24, are more subjected to joblessness. Youth are more susceptible to a lack of experience, social networks, and various talented capacities that would have made it hard for them to hunt down businesses. In numerous parts of the globe, youth was almost three times more probably to be unemployed when compared to adults (ILO, 2012).

According to estimates, the COVID-19 pandemic's economic situation would increase global unemployment by more than 200 million people the following year, disproportionately affecting women and young workers in urban areas. (Alen Cameron et al., 2021). Youth are among the most massive menacing essentials and assets a nation needs to construct its social and economic development. Similarly, they are immense in number; they are passionate and courageous and produce novel ideas that can transform social and economic development if they are well-managed and participate in the country's economic activities. Autonomous of such standing, youth, especially from urban areas, have faced considerable challenges, including joblessness (Tu, 2022).

One of the significant issues in both developed and developing countries is youth unemployment (LFS, 2013). Youth unemployment results in disappointment, hopelessness, and grief. These situations are sure to worry young people who engage in risky and harmful behavior. Young people's risky behavior adversely affects their well-being, family networks, and the country's general population. They could potentially be ineffective, depressed, and at high risk of drug and alcohol abuse, delinquency, and criminal activity, which might eventually lead to social unrest and civil unrest. (Mroz and Timothy, 2006).

Unemployment continues to be a severe social concern in Ethiopia, regardless of some improvements that have been made in current years. Ethiopia's unemployment rate for 2020 was 2.79%, a 0.75% upsurge from 2019. At the national level, Ethiopia's youth unemployment rate was 27%. (LFS, 2013). In 2011, the young and children's population alone made up 41% of Ethiopia's total population, demonstrating the country's enormous predominance of people, especially young people from metropolitan regions (CSA, 2012). Youths from Ethiopia's metropolitan regions encounter job market challenges, such as unemployment, low-paying, low-skilled positions without opportunities for professional growth, and typically working amid insufficient vernacular economic activity. Youth work spreads discrepancies from one country to the next, and some countries have more significant issues than others.

Despite recent improvements, underemployment has remained a severe societal issue in Ethiopia, according to Martha (2012), who also found that unemployment is an urban phenomenon. Ethiopia's urban youth unemployment issue is getting worse very quickly.

The entry of young people into the workforce has long-term effects on the socioeconomic development of their countries and their own lives. Several governments at various development stages are trying to solve this issue. According to the International Labor Organization's definition from 2015, unemployed people are those who, when asked, claim to be keen and competent to work more hours than they are presently putting in. Additionally, persons who choose not to be prepared for employment, full-time students, the elderly, and children, are excluded from this category. Therefore, unemployment represents a situation in which people are capable and want to work but cannot land their ideal position. The issue of youth unemployment affects most nations. Youth involvement in practical activities impacts that nation's social and economic dynamics. However, young people in most countries are more likely than adults to be unemployed. As more and more young employees enter the African labor market each year, the preadolescence unemployment rate in North Africa was 30.2 percent in 2019, compared to an overall unemployment rate of 12.1 percent and 8.7 percent in sub-Saharan Africa. Building employment possibilities is becoming progressively more essential. The current employment situation in Africa shows that youthful workers encounter deeply established honorable work deficits and enduring occupations (ILO World Employment and Social Outlook Trends, 2020).

The concept of unemployment has many facets and affects people on political, social, and economic levels. We cannot offer a general definition of youth unemployment since it depends on any individual nation's social, cultural, economic, institutional, and educational systems. United Nations defines "youth" as people between 15 and 24 years who do not have their definitions influenced by those of the Member States. In Ethiopia, youth are defined as individuals between the ages of 15 and 29. According to the World Health Organization, "Young People" encompasses those between the ages of 10 and 24. "Adolescents" are defined as those between the ages of 10 and 19, and "Youth" as those between the ages of 15 and 24.

According to ILO (2018) figures, Sub-Saharan African labor markets are distinct from those in North Africa. Sub-Saharan employment revealed widespread low-productivity involvement in smallholder farming. This percentage is expected to increase due to the sub-slower regions' average rate of poverty decline. With 89.2 percent of workers, informal employment is the norm. Even without agricultural employees, the informality rate remains at 76.8% (ILO, 2018).

Youth's poor work position has several political, ethical, and social repercussions (Berhanu et al., 2005; Toit, 2003). Drug abuse among youth is one of the effects of unemployment. Unemployed young ones are more likely to devour illegal substances than employed ones. According to the UN (2003) report, most drug users in Sub-Saharan Africa are young people without jobs, making up 34 million young individuals and 7.7% of Africa's youth. The data also demonstrates that marijuana, or Cannabis, is the immediate drug used by young people in the region. Likewise, Curtain (2001) noted that misbehavior, criminality, and drug abuse are on the rise among young people without jobs in the continent.

One of Ethiopia's most pressing socioeconomic issues is the country's high rate of unemployment and underemployment. Despite an alarmingly high proportion of young people entering the labor force, more than job growth is required to attract new workers. Youth are consequently negatively impacted by unemployment. Additionally, young people may be operating in low-quality positions, underemployed, working longer hours for lower pay, employed in dangerous jobs, or obtaining only temporary or daily wage type of employment positions (Berhanu et al., 2005).

For urban young people in Ethiopia, unemployment is a more serious issue than it is for adults. According to data from Ethiopia's central statistics survey, the unemployment rate among young people was higher than it was for the adult and older age groups (CSA, 2020).

Therefore, identifying the pronounced traits contributing to the unemployment of youth living in urban areas should be the foremost measure in developing alternative strategies to solve the issue. Even though extensive studies on the factors that contribute to young unemployment in Ethiopia have been conducted (Duguma et al.,2019; Ahemedteyib, 2020; Tsegaw, 2019; Gebeyaw, 2011; Asalfew, 2011; Tegegne, 2011; Asmare, 2014; Nganwa et al., 2015; Aynalem et al., 2016; Dejene et al., 2016 and Getinet, 2003), Depending on the specific socioeconomic situation and methodological discrepancies of the subject location, the results of such investigations vary. Therefore, the current study investigates the factors contributing to urban youth unemployment in Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode and Dollo Addo in Ethiopia's Somali Regional State.

Problem Statement

One of Ethiopia's serious socioeconomic problems is its high unemployment rate, which occurs as a growing share of young people enter the labor force, particularly those from metropolitan areas. Urban youth are hence particularly affected by unemployment. Additionally, young individuals from metropolitan areas often work in low-quality occupations (Shah, 2017). Only temporary or informal employment situations are available to those unemployed, working long hours for low earnings or performing unsafe work (Mroz & Timothy, 2006; Shah, 2016).

Ethiopia now faces significant issues with unemployment, just like many other developing nations. Unstable economic conditions are brought on by the unjustified unemployment rate, which has a detrimental effect on the economy. Because resources are not adequately utilized in these countries, total production in those nations is below its potential level, which contributes to the decline of a healthy society (Maqbool et al., 2013). In addition to managing their lives as expected to support parents and dependent families, youth from metropolitan regions are particularly affected by unemployment, which has broader implications for Ethiopia (Shumet, 2011; Shah, 2016).

Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode and Dollo Addo being urban towns in the region, manifest the problem of youth unemployment. The unemployment results of these cities are demonstrating urban youth pessimism and social marginalization, which necessitates comprehensively examining the factors influencing young unemployment in such metropolitan areas.

The current study reveals the numerous difficulties that urban youth unemployment and particular circumstances provide for the possibilities for work in these locations. Numerous young people in these areas are constrained by the difficult circumstance of unemployment, which has generally forced them to endure unspeakable agony and live in substandard conditions. To create chances like giving capital through microfinance institutions, the state and other parties like NGOs and the corporate sector have worked hard. However, the educated have remained unemployed, and numerous government initiatives to address the challenge of young urban unemployment have yet to be as effective as anticipated.

Despite repeated efforts by the government and development partners, Ethiopia needs help with urban youth unemployment. It causes numerous social and economic issues in the nation's economy. Even though unemployment is a severe issue at the national level, this study was limited to just five cities in the Somali regional state due to a lack of funding. To fill the research gap, the current study was concentrated on factors influencing urban youth unemployment in the the Somali regional state.

Significance of the study

Youth unemployment standing a tormenting crisis in Ethiopia, notably in the Somali region. The study by Ahemed Teyib Kemal, 2020; Tsegaw Kebede, 2019; and Esay Solomon, 2020 attempts to indicate the determinants or the explicit factors that lower youth employment. This study is interesting since it discusses the factors contributing to the high young unemployment in the five city administrations of Somali regional state.

Since the study is limited to large cities in the Somali regional state, it will be helpful to analyze the causes of young urban unemployment in Ethiopia. It offers some hints as to the nature and scope of the difficulties brought on by the high level of youth unemployment. The government and policymakers must assess the policy gaps related to country employment to manage the unemployment issue. Therefore, knowledge of the factors that determine urban youth unemployment is crucial. Employers and other labor market participants will find the study's findings helpful in understanding the determinant factors that have left a significant portion of the workforce in the country's young unemployed. Additionally, the study simultaneously provides information to help young people in the Somali region understand the determinant factors of unemployment and provide potential solutions. The study's findings will also serve as a benchmark for additional examination and further research in market policy issues.

Materials and Methods

This section demonstrates the research strategy to finish the study, including the research design, sample size, population size, and data collection method. This research assessed determinant factors impacting urban youth unemployment in the Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode and Dollo Addo towns of the Somali regional state. IBM SPSS and STATA software have been used to test the data obtained from the questionnaire using descriptive, inferential and econometric analysis.

In this research, the case study and deductive approach were used. This research aims to describe what is happening in more detail and increase our understanding of existing knowledge.

The instrument used for primary data collection

The primary data was compiled using an interview schedule enfolding all the needed factors. The Interview schedule was used to collect data from the youth belonging to the urban areas of Somali regional state specifically from Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode and Dollo Ado cities, as mentioned. For the easy understanding of questions by the respondents, translation of the questionnaire into the local language (Somali) was done. The study area was used to find skilled enumerators. Before the in-person Interview, a pre-testing study was conducted with a small number of responders. The interview questions were then changed to maintain the integrity or credibility of the study.

Pre-testing

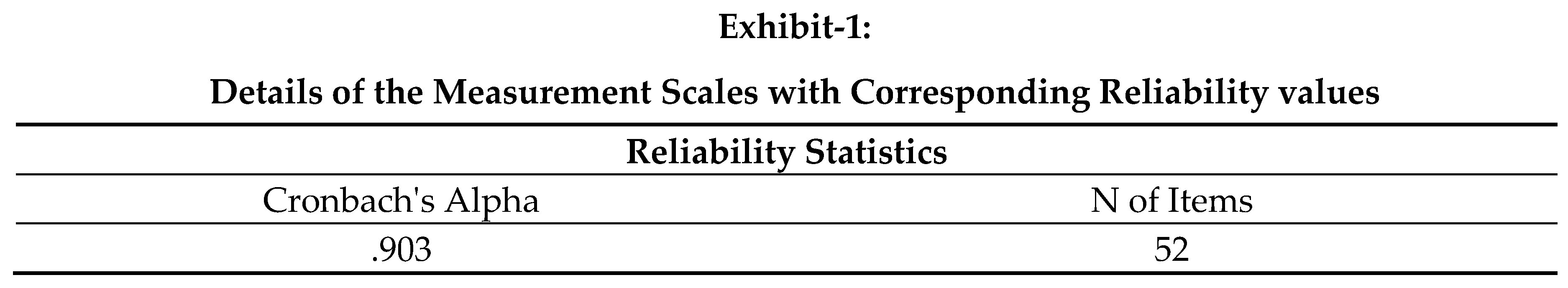

To assess the internal validity of the current research, a pilot study was conducted (questionnaire). 60 respondents provided the primary data that were needed for this goal. The outcomes of the pilot research proved the instrument's internal reliability. Therefore, the same method was applied to identify sampling sites to gather the primary data required for the current investigation.

Survey Instrument Reliability

The survey instrument underwent proper reliability testing, which included computing Cronbach's alpha. All the study variables included in the survey instrument had an alpha value significantly higher than the advised level of 0.730 (Nunnally, 1978). The following table displays the precise information regarding the alpha value for each study variable that makes up the current work:

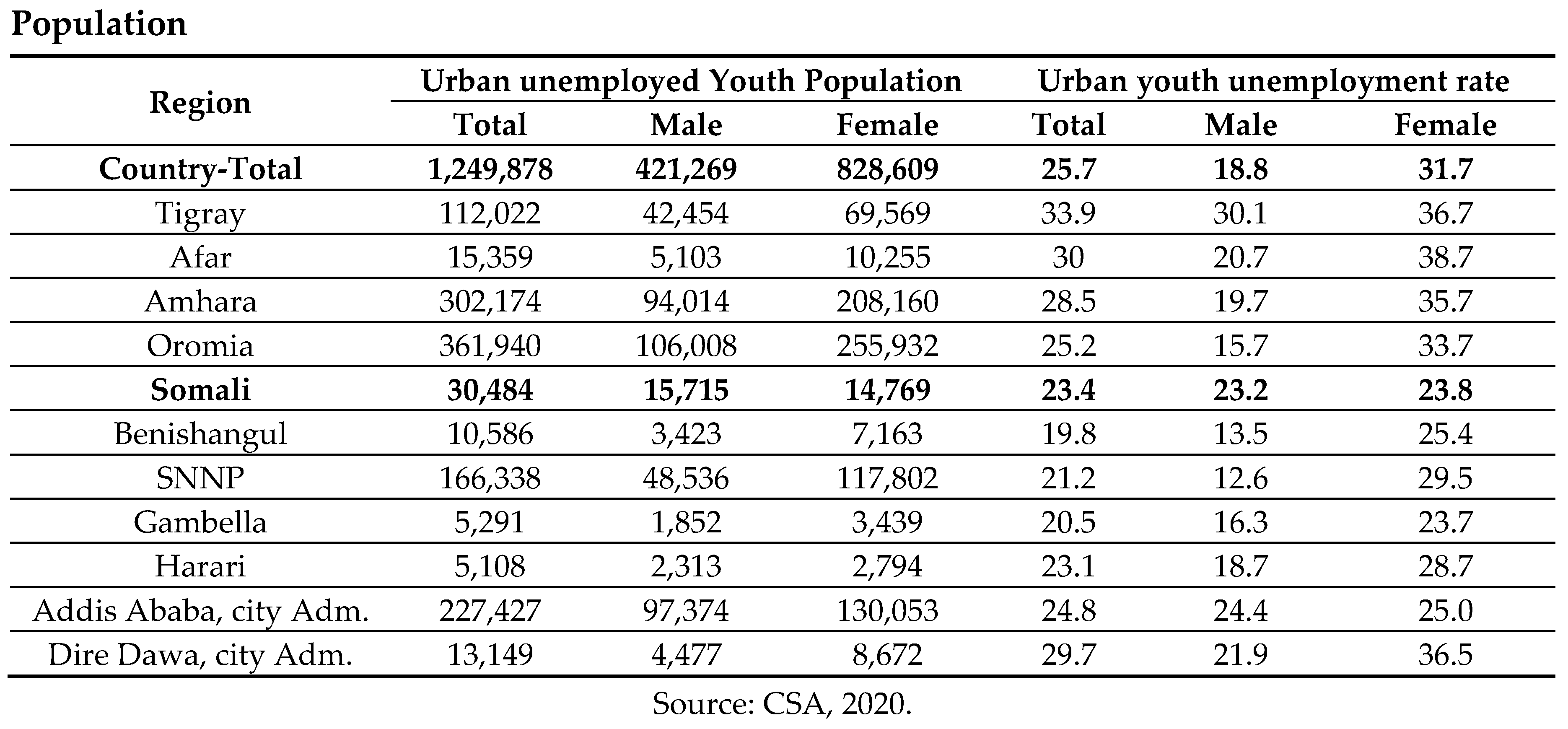

Population

Due to the country’s rapid population growth and burgeoning economy, the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia conducts several population-related surveys, including inquiries into youth employment and unemployment rates, to ensure good management and effective use of the country's labor force. In order to offer information about the economically engaged urban youth population in Ethiopia's regional states, the CSA collected the data presented below in Table BBB in January 2020. This study used 30,484 urban unemployed youth population in Somali Regional State as the study population and the sample size was calculated using Kothari's (2004) sample size determination formula.

Sampling Size

The sample size of the respondents can be chosen by using Kothari's (2004) sampling design procedure:

Where n = sample size; N = total of urban unemployed youth population in Somali regional state (30,484); Z = 95% confidence interval; e = permissible error term (0.05), and P and q are estimations of the ratio of the population to be sampled (P = 0.5 and p + q = 1). 5% of the error term (e = 0.05) was utilized to collect samples for this study. The sample size for the analysis was decided as follows:

By considering non-responding rate the study sample were increased by 4% which makes the final sample size as a 395 and finally the data were collected successfully from 385 sample respondents.

Sampling Technique

The sample is considered a subset of the population; sampling is selecting a piece representing the total population (Biondo et al., 1998). A multi-stage sampling technique has been used for this study. In the first stage, the Somali regional state was selected purposefully; in the second stage, five cities in the region were selected based on the large number of youths living in those cities; in the third stage, 15 kebeles (three from each town) were selected based on city administration recommendations; and in the fourth stage, respondents were selected using a simple random sampling technique. An authorization letter was conjoined at the commencement of the questionnaire; if somebody was unwilling to fill it out, they had an option to not partake in the survey. In the final stage, further questions would appear if the respondent were keen to fill out the questionnaire.

Method of Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and econometric data analysis models were used to analyze the sample respondents' data. Descriptive statistical methods of data analysis were also employed. Concerning inferential statistics, logistic regression, chi-square, and ANOVA techniques were used to compare the informational aspects of the unemployed urban youths in the study area. The methodological framework and choice of statistical tools based on research objectives were tested. Based on this fact, the binary choice econometric model (logistic) estimation method was employed to examine the socioeconomic determinants of urban youth unemployment in the study area.

Dependent and Independent Variables description (Operationalization)

Fourteen numbers of explanatory or independent variables are stated and estimated in the model of this study, which uses one dependent variable to derive key statistical conclusions about unemployment status.

Model Specification

Urban youth unemployment is the dependent variable of this study. This latent variable allows people to be classified as either employed or jobless. The binary logit or probit estimation approach is the appropriate econometric method for analyzing such a binary decision. In order to analyze the socioeconomic causes of urban adolescent unemployment in the research area, this study used a binary probit regression model. The probit model can be determined as:

Where y* is the likelihood of being unemployed for the individual i and linear relationship with the potential factors specifying urban youth unemployment, Xis whereas β is the slope parameters of determinants and µi is the stochastic error term which takes consideration for all potential determining aspects of urban youth unemployment.

Young people's unemployment in metropolitan areas is influenced by personal traits like age, gender, education, marital status, social network, and family traits like parents' jobs, educational attainment, income, job preference and location. Most studies examining the factors responsible for unemployment in broad, specifically youth unemployment, use these elements extensively. (Abebe Fikre, 2012; Alhawarin and Kreishan, 2010, and Bhorat, 2008).

Unemployment = f (gender, age, educational level, family size, social network, work experience, parents' education, parents' income, access to credit, access to information, job preference, time applied for job, and location).

Although it is impossible to monitor a person's unemployment status directly, potential causes can be inferred from their reaction. We can track the determinants' overall impact on the likelihood of getting employed (

) or unemployed (

=1)

The error term, has a binomial distribution and its variance conditional on is:

Using Equation (1) and (2), the probability of getting unemployment can be modeled as:

Φ (.) symbolizes a cumulative distribution function (CDF). The parameters of binary choice models are calculated using the maximum likelihood estimation method. For each person, the probability of being unemployed is conditional on several factors like age, gender, educational level, family size, marital status, social network, parents' employment status, parents' education, parents' income, location or living city, and access to credit. The same is calculated as:

The log likelihood for each individual can then be set as:

The log-likelihood for each individual can then be set as follows:

Probit and logit estimation are two generally used estimation techniques for binary choice models. The distinction between these two models is that the probit model's incremental distribution function (IDF) follows the normal distribution. However, such a type of distribution does not operate for the logit model. It has logistic distribution.

Standard logistic distributions have a mean of 0 and a variance of 5, compared to the standard normal distribution's mean and variance of (Verbeek, 2008). Both estimation approaches yield identical results in applied work, excluding the cumulative distribution function difference. This study will use the logistic/probit estimation approach to assess the factors specifying unemployment in the study areas. This method was used in various studies to study the determinants of unemployment in Ethiopia (Abebe Fikre, 2012; Cattaneo, 2003).

It is difficult to directly understand the estimated parameters following analysis of the probit or logit model since they only represent the sign of the shift in the variable, which is dependent on a shift in the descriptive variables (Abebe Fikre, 2012). As a result, the following table shows how each determinant's impact on the likelihood of unemployment changes:

Equation (7) shows that the derivative of the distribution function evaluated at the latent variable ( and the effect of the determinant ( on the latent variable ( are the factors that determine how a change in a particular determinant ( affects the chance of being unemployed.

Source of Data

There were both primary and secondary data sources used. The primary data was gathered using an interview schedule that included all the necessary parameters. As previously noted, the interview schedule was utilized to collect data from young people living in Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode and Dollo Addo. To make the questionnaire easier for the respondents, it was translated into Somali. The study area was used to find skilled enumerators. Before the in-person Interview, a pre-testing study was conducted with a small number of responders. The interview questions were then changed to maintain the accuracy or reliability of the study.

Data Analysis

Data were examined in the study using IBM SPSS and STATA software. Data processing included editing, coding, and tabulation, which were crucial steps in the research process. The data were cleansed before entering the latest version of IBM SPSS software 28 and STATA software 64.

Descriptive and Inferential Analysis

To have a clear picture of the socio-economic characteristics of the sample units and present research results, descriptive statistics such as mean, standard error, standard deviation, percentages, and inferential statistics like the student t-test (for continuous variables) and the chi2-test (for categorical variables) have been used.

According to

Table 1, the study sample respondents (385 in number) were asked whether they were currently employed or not, and 144 (37.40%) of the sample respondents answered that they were employed, whereas the majority of the respondents, 241 (62.60%), were currently unemployed. This table also indicates that the response rate of this study is 100 percent with a total sample size of 385.

Student t-test analysis for continuous variables

Age of the respondents: According to the study result presented in

Table 2, the mean age of the sample respondents who are employed was 25 years (Std. Dev. =4.22), whereas the mean age of the sample respondents in the unemployed group was 23 years (Std. Dev. =3.73), respectively. The age differences between the two groups (employed vs. unemployed) were found to be statistically significant (p-value = 0.02) with a t-value of -3.12, which indicates that age has a significant effect on individual employment status in the study area.

Work experience: According to the study result presented in

Table 2, the mean years of working experience of employed sample respondents was almost 5 years (Std. Dev. = 2.56), whereas the mean years of working experience for unemployed group was found to be almost one year, respectively. This indicate that the mean years of experience between the two groups was found to be statistically significant at 1% level of significance (p-value=0.00) and having the t-value( of t= -22.03). This implies that working experience effect on employment status of the interviewed sample respondents.

Time applied for job: Time applied for job was included into the variables or questions that has been asked the sampled respondents which indicate how many times they were applied for jobs. The sample respondents who are employed were answered they were applied for open job vacancy on average 6 (six) times whereas unemployed sample respondents where answered they were applied for job vacancy 2.701 times which is almost 3 (three) times. According to this finding individual in sample who are employed were applied more time than those who are not employed and the difference in their mean times applied for job was statistically significant (p-value = 0.00) with at t-value (t = -15.92). This indicate that time applied for job has significant effect on the individual employment status in the study area.

Education level: According to the study results presented in

Table 2 below, the mean years of schooling for employed sample respondents was 13.92 (Std. Dev. = 3.24) whereas the mean years of schooling for unemployed sample respondents was found to be 8.278 (Std. Dev. = 4.70). This indicate that there was a significant difference between the two groups (employed Vs. unemployed) in their mean year of schooling at (p-value = 0.00). Therefore, study results reveal that increasing in the year of schooling has a significant effect in employment status of the respondents in the study area.

Household monthly income: According to the study result presented in

Table 2 below, the mean monthly household income of the employed sample respondents was 8209.23 Ethiopian birr (Std. Dev. = 6118.54), whereas the mean monthly household income of the unemployed sample respondents was 5835.35 (Std. Dev. = 7629.55), respectively. The mean monthly household income differences between the two groups (employed vs. unemployed) were found to be statistically significant (p-value = 0.02) with a t-value of -3.17, which indicates that monthly household income has a significant effect on individual employment status in the study area.

Household family size: The study results presented in

Table 2 below, indicate that the mean household members of the sampled respondents were 2.46 and 2.45 for employed and unemployed sample respectively. This indicate that there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of their household size (p-value = 0.95). Therefore, this study result reveal that the mean difference in household size between the two group has no effect on employment status of the individuals in the sample.

Chi2-test analysis for dummy and categorical variables

The descriptive analyses of Pearson’s chi-square proportion difference test between employed and unemployed individuals in the study sample for both dummy and categorical variables were presented in the below

Table 3, and the result of each variable was presented separately as follow:

Sex of the respondent: According to research finding presented in

Table 3, the total sample of 240 (62.34%) were male youth whereas 145 (37.66%) were female youth, respectively. Employed male youth represent 82.64 percent whereas employed female youth represent only 17.36 percent in the study area. Similarly, unemployed male youth 50.21 percent and unemployed female youth were 49.79 percent in the study area. The difference in employment status between male and female urban youth in the study area was statistically significant at 1% significance level (p-value = 0.00) with chi2-value of 40.38 which implies that, female youth has less chance to be employed than female in the study area.

Access to credit: According to study results presented in

Table 3, the total sample of 174 (45.19%) have access to the credit whereas 211 (54.81%) of the total sample respondents were have no access to the credit, respectively. Based on the study finding 139 (96.53%) of employed youth have access to credit whereas only 5 (3.47%) of employed youth have no access to credit in the study area. Similarly, 206 (85.48%) of unemployed youth have no access to the credit whereas only 35 (14.52%) of unemployed youth have access to the credit in the study area. This indicate that the difference between employment status between the two groups (access to credit Vs. No access to credit) was found to be statistically significant at 1% percent significance level (p-value=0.00) with chi2-value of 244.73 which implies that access to credit has significant effect on employment status of the urban youth in the study area.

Access to job vacancy information: According to study results presented in

Table 3, the total sample of 165 (42.86%) have access to the job vacancy information whereas 220 (57.14%) of the total sample respondents were have no access to the information related with open job vacancy, respectively. From the sample 115 (79.86%) of urban youth who have access to job vacancy information were employed whereas 29 (20.14%) of urban youth who have no access to information to the job vacancy where also employed. Similarly, 50 (20.75%) of unemployed urban youth where have access to the credit whereas the majority 191 (79.25%) of unemployed urban youth have no access to the credit in the study area. This indicate that there is a significant difference between the two groups (access to job information Vs. no access) in their employment status and this difference is statistically significant at 1% level of significance (p-value = 0.00).

Active job seeker: According to study results presented in

Table 3, the total sample of 230 (59.74%) were active job seeker whereas 155 (40.26%) of the total sample respondents were not actively seeking job due to different reasons. From the sample 139 (96.53%) of active job seeker urban youth were employed whereas 91 (37.76%) of active job seeker urban youth are not employed. Similarly, the majority 150 (62.24%) of those who were no active job seeker were unemployed only 5 (3.47%) of those who were not active job seeker were employed. This indicate that being active job seeker has a significant effect on employment status of urban youth in the study area and this is statistically significant at 1% percent level of significance (p-value = 0.01).

Having social network: The study finding presented in

Table 3 below, indicate that the total sample of 236 (61.31%) had a social network with their friends, clan elders and government officials whereas 149 (38.75%) of the sample respondents have no social network. Based on this study finding 134 (93.06%) of urban youth who have strong social network had employed whereas 102 (42.32%) of the sample respondents who have social network were unemployed. Similarly, 139 (57.68%) of the unemployed urban youth have no social network whereas very small number 6.94% of who have no social network were employed. This indicate having strong social network with friends, clan elders, business man and government officials had significant effect on employment status of urban youth in the study area (p-value = 0.00).

Job Preference: It was hypothesized that the job preference of youth can determine the employment status of urban youth in both a negative and positive way. According to the study findings presented in

Table 3 below, 60.4 percent (87) of youth who prefer self-employment are currently employed, while 18.26 percent (44) of them are not employed. In addition to this, this study indicates that a large number of youths who prefer paid jobs both in the public and private sectors were not employed (75.52 percent), and only 26.39 percent (38) of youth who prefer paid employment were employed. Therefore, this study argues that job preference by youth has an effect on youth employment status, as hypothesized by the researcher, and there is a significant difference among the youth in their job preference and employability, with a significant difference at the 1 percent significance level.

Youth unemployment and resident: The sample consists of youths from Jigjiga, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, Gode, and Dollo Addo. According to the study findings presented in the below

Table 3, the percentage of youth unemployed in these towns was 26.16%, 21.58%, 20.33%, 16.6%, and 15.35% in Jigjiga, Dollo Addo, Dagahbour, Kebridahar, and Gode, respectively. This indicates urban youth unemployment is higher in Jigjiga, followed by Dollo Ado, as compared to other towns in the Somali regional state. Therefore, this study argues that there is a significant difference between towns in the region in respect of their youth employment status, and this difference is statistically significant at the 1% level of significance (p-value = 0.02).

Multicollinearity test

The variance inflation factor (VIF) has been used to calculate the correlation matrix of the independent variables. To report multicollinearity, this study tried to apply methods such as feature selection to the chosen subset of independent variables that are not correlated with each other at a higher level. The technique of VIF describes the strength of the correlation among the independent variables. This is forecasted by selecting a variable and regressing it compared to the other variable. And from the below table, we can see that all the values are below 2.17, and the mean VIF also stands at 1.53, so it is evident that there is weak multicollinearity among the independent variable and the other variables. This means that the independent variables cannot be forecasted by other independent variables in the data set, but rather by the dependent variable.

Table 4.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) result.

Table 4.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) result.

| Variable |

VIF |

1/VIF |

| Gender, male |

1.22 |

0.822232 |

| Age |

1.24 |

0.805851 |

| Education level |

1.54 |

0.647335 |

| Family size |

1.06 |

0.942045 |

| Work experience |

2.17 |

0.459914 |

| Household income |

1.24 |

0.807608 |

| Parental Educ |

1.18 |

0.846042 |

| Access to credit |

2.05 |

0.488619 |

| Access to Info |

1.72 |

0.581041 |

| Time applied for job |

1.55 |

0.646635 |

| Active job seeker |

1.48 |

0.677796 |

| Social network |

1.34 |

0.745122 |

| Job preference |

1.13 |

0.883149 |

| Living in Jigjiga |

1.85 |

0.540564 |

| Living in Dagahbour |

1.66 |

0.601356 |

| Living in Kebridahar |

1.75 |

0.572371 |

| Living in Gode |

1.75 |

0.570058 |

| Living in Dollo Ado |

1.65 |

0.605694 |

| Mean VIF |

1.53 |

Econometric Model Results

This study used the econometric technique of odds ratios for the binary logistic model to compare the odds of two events, which are unemployment and employment. The technique helps us to understand the likelihood of the presence of unemployment at odds with the likelihood that unemployment ceases to exist. So, we can see from the below table that the odds ratios for variables like gender, education level, family size, work experience, household income, access to credit, access to information/job vacancy, time applied for a job, activeness of the job seeker social network, and youth living in cities like Dagahbour, Kebridahar, and Gode have odds ratio values greater than 1, which indicates that the event is less likely to occur as the predictor increases. And on the other hand, the odds ratios for the variables like age of respondent, parental education level, and job preference for paid employment, whose values are less than 1, indicate that the event is more likely to occur as the predictor decreases. In these results as shown in the below table, the model uses the different independent variables to predict the presence or absence of employment among the respondents.

The logistic regression method was used to identify the various determinants of unemployment in the study areas. The dependent variable which is urban youth unemployment status of the youth and the same takes the value equal to 0 if the individual is employed or 1 otherwise. As specified in the below table 5, the general goodness of the fit of the model test shows that the model is correctly quantified, at the 1 percent significant level and 88.7 percent variation in the dependent variable is clearly explained by independent variables included in the model.

Discussing the results presented in the below table 5, gender plays a major role and it is visible that young males compared to the females have lesser risk of unemployment in the study area. The coefficient is significant at the 5 percent significance level, which shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a factor of 4.50 for the males when compared to the females in the study area.

There are also differences in the educational or skill training level of the youth; those who are highly educated are associated with lower levels of unemployment risk. According to the results, the coefficient is significant at the 10 percent significance level, which shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a factor of 1.20 for the highly educated youth when compared to the low educated youth in the study area.

The variables like activeness of the youth for job seeking and the role of social network for reducing the unemployment levels in the study area are also clearly demonstrating that both the variables are highly influencing the dependent variable. According to the results, the coefficient is highly significant at the 1 percent significance level, which shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a large factor of 48.93 for the youth who are the active job seekers, when compared to the less active job seeker youth in the study area.

Having social network and actively using social media, by holding other factors constant the results depict the coefficient as highly significant at the 1 percent significance level, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a large factor of 45.40 for the youth who have strong social network (having network with clan elders, government officials, respected business man, active using social media) as a tool for job searches, when compared to the youth who do not have such social network for the same in the study area

Regarding the work experience it is found that youths who have higher work experience were less likely to be unemployed. The odds ratio of being unemployed increases by 4.49 if the individual has a higher experience compared to those who are having less experience.

Access to information, and job vacancies plays a major role in the study area. The coefficient is highly significant at the 1 percent significance level, which shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a factor of 13.75 for the youth having access to the information about the jobs when compared to the youth who are lacking the information about the jobs in the study area.

Likewise, the youth who are continuously searching and applying for the jobs are found to be less unemployed as compared to the ones, applying recently. The coefficient is highly significant at the 1 percent significance level, which shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a factor of 2.56 for the youth having access to the information about the jobs when compared to the youth who are lacking the information about the jobs in the study area.

Concerning the family size, it is found that youths who live in a large family were less likely to be unemployed. The odds ratio of being unemployed decreases by 1.61 if the individual is a member of a large family compared to those who are living with a small family. And nearly the same results are found regarding the access to credit by the youths, it is found that youths with access to credit were less likely to be unemployed. The odds ratio of being unemployed decreases by 1.79 if the individual has the access to the credit compared to those who are lacking the access to credit.

There is very less or no differences regarding the household income of the youth and their unemployment status. According to the results, the coefficient shows that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio is not having much decreasing effect for the whose income is high when compared to the less income households.

The variables like age of the youth, their parental education, and their job preference for the paid employment are also clearly demonstrating that all these three variables are not influencing the dependent variable. According to the results, the coefficients show that, holding other factors constant, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a meagre factor of 0.88 for the youth who are the aged more, when compared to less aged youth. Similarly, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a meagre factor of 0.96 for the youth whose parents are highly educated, when compared youth whose parents are less educated. In the same way, the odds ratio in favor of being unemployed is decreased by a meagre factor of 0.86 for the youth who prefer paid employment, when compared with the youth who have no preference for the paid employment.

Five towns/cities administration variables were entered in the estimation model to understand and analyze differences of unemployment among the various towns in the Somali regional state. The result demonstrates that, controlling for other variables, the occurrence of unemployment is found to be to be lesser in the cities like Kebridahar and Gode with significance level of 5 percent and 10 percent, respectively. Similarly, the model coefficients of Dagahbour and Dollo Ado shows that the occurrence of youth unemployment found to be lesser but their respective coefficients indicated as insignificant. The model results also illustrate that youth living in Jigjiga are more likely to become unemployed. From this result, it can be understood that the more urbanized areas of the Somali region, like Jigjiga, have a higher prevalence of youth unemployment. It may be due to the high migration of labor into Jigjiga town from other places, including other urban areas of the region, by the youth in the hope of job searches.

Table 5.

Determinants of urban youth unemployment -logistic model results.

Table 5.

Determinants of urban youth unemployment -logistic model results.

| Variables |

Odds Ratio |

Std. Err. |

Z-value |

P>IzI |

[95% Conf. Interval] |

| Gender, male |

4.501674** |

3.830135 |

1.770 |

0.077 |

0.8494755 |

23.85598 |

| Age of respondent |

0.880524 |

0.115063 |

-0.970 |

0.330 |

0.6815713 |

1.137551 |

| Education or skill training level |

1.201957* |

0.145901 |

1.520 |

0.130 |

0.9474685 |

1.524810 |

| Family size |

1.610416 |

0.631184 |

1.220 |

0.224 |

0.7470008 |

3.471805 |

| Work experience |

4.494417*** |

1.775463 |

3.810 |

0.000 |

2.1592160 |

9.748321 |

| Household income |

1.000840 |

0.000295 |

0.158 |

0.889 |

0.9999464 |

1.000856 |

| Parental education level |

0.962392 |

0.128184 |

-0.294 |

0.778 |

0.7412762 |

1.249465 |

| Access to credit |

1.795969** |

0.584025 |

1.803 |

0.072 |

0.9495096 |

3.397021 |

| Access to Information, vacancy |

13.75985*** |

13.00197 |

2.770 |

0.006 |

2.1592160 |

87.68626 |

| Time applied for job |

2.567959*** |

0.590106 |

4.130 |

0.000 |

1.6367620 |

4.028937 |

| Active job seeker |

48.93078*** |

63.33948 |

3.301 |

0.003 |

3.8701270 |

618.6406 |

| Social network |

45.40834*** |

63.63821 |

2.720 |

0.006 |

2.9221010 |

708.0516 |

| Job pref., paid employment |

0.869003 |

0.569209 |

-0.210 |

0.830 |

0.2406961 |

0.137406 |

| Living in Jigjiga |

0.490808** |

0.1626909 |

-2.15 |

0.032 |

0.2563059 |

0.9398621 |

| Living in Dagahbour |

3.286249 |

4.170243 |

0.940 |

0.348 |

0.2732294 |

39.52514 |

| Living in Kebridahar |

26.60592 |

39.18085 |

0.223 |

0.026 |

1.4841150 |

476.9067 |

| Living in Gode |

6.822366** |

9.168674 |

1.430 |

0.153 |

0.4897713 |

95.03351 |

| Living in Dollo Ado |

3.753853 |

6.324995 |

0.790 |

0.432 |

0.1381207 |

102.0225 |

| Log likelihood |

= -28.72659 |

| Number of Obs. |

= 385 |

| LR chi2 (18) |

= 18 |

| Pro > ch2 |

= 0.000 |

| Pseudo R2 |

= 0.887 |

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

In every nations of the world, youth are its best hope for the future. One of the most pressing socioeconomic issues in Ethiopia is youth unemployment. In this regard, several studies have been carried out so far in order to examine the causes of youth unemployment and its consequences on the nation’s economy. These efforts generate a broad range of results. This study focuses on the factors that determine urban youth unemployment in Somali regional state.

As it was discussed earlier, this study focuses on the assessment of urban youth unemployment determinant factors from a socioeconomic and demographic perspective. Therefore, this conclusion part presents the major findings of the study and the variables that significantly determined the dependent variable (urban youth unemployment status in the Somali region).

Using cross-sectional data collected from urban youth in the region, specifically from Jigjiga, Degahbour, Kebridahar, Gode, and Dollo Addo towns, this study investigated the socio-economic determinant factors affecting youth unemployment status in urban areas. The study results state that almost 63% of the urban youth in the Somali regional state were unemployed, according to data collected from 385 youth respondents living in these towns. Both descriptive statistics and econometric model results reveal that urban youth unemployment is high in Jigjiga and Dollo Ado towns of the region as compared with other urban areas of the Somali region.

A binary logistic econometric model is employed to understand the determinants of urban youth unemployment, which compares the odds ratio of the two events (employment and unemployment). The general goodness of fit of the model test shows that the model is correctly quantified at the 1 percent significant level, and the 88.7 percent variation in the dependent variable is clearly explained by independent variables included in the model. According to the model results, variables like gender (being male), education level, work experience, access to credit, access to information, time applied for job vacancy, active job seeker, having social network (network with clan elders, government officials, businessmen, and other friends), and living in Gode town are significantly and negatively determining urban youth unemployment in the Somali regional state. In contrary to this, living in Jigjiga as a variable is statistically significant and positively determining urban youth unemployment.

This study found that gender plays a great role in determining urban youth unemployment in the Somali regional state and basically showed that female youth have a high risk of being unemployed as compared to males. This shows that there is gender inequality for any job available in the region, which needs proper policy and government intervention. Therefore, this study recommends that the regional government and local city administration develop effective policies and strategies to address the underlying causes of gender inequality in employment opportunities and provide opportunities for female graduates. In addition to this, awareness creation for female urban youth is highly recommended since they are not yet active in job seeking, even those who graduated from college or universities.

Education or life skills training level is found to be one of the major determinants of urban youth unemployment in the study area. Study results reveal that by holding other determinant factors constant, the risk of being unemployed is decreased for urban youth who have a high education or skill training level as compared to others. Therefore, this study recommends that access to education and life skills training for urban youth should be improved by the regional government and local city administrations. And also, other stakeholders, like Jigjiga University, Kabridahar University, and TVET colleges located in the Somali regional state, should actively participate in educating and giving short- and long-term life skills training to urban youth in the region.

Work experience and having a strong social network were found to be significant determinant factors for urban youth unemployment in the study area. Urban youth who have no experience and have no strong relationship with clan elders (ugaas), government officials, or respected business owners have a high risk of being unemployed as compared to those who have experience and a strong social network. This implies that there is an unfair employment system in the region in which social bonds have a significant role in the employability of youth, irrespective of their qualifications. Therefore, this study recommends that employment opportunities in the region should be fair and based on merit. Additionally, university or college freshmen graduates should be given attention in both the government and private sectors.

Access to credit is found to be one of the determinants of urban youth unemployment in the study area. The study results found that access to credit by youths has a significant role in youth employment status, and it was found that youths with access to credit were less likely to be unemployed as compared to those who have no access to credit. Loan provision by microfinance institutions like Somali microfinance (current Shabelle Bank) has had a positive impact on increasing employment opportunities in the region, and urban youth who have access to Somali microfinance are less likely to be unemployed. Therefore, this study recommends the implementation of accessible credit provision institutions. Regional macro-policies entail guaranteeing macroeconomic stability, maximizing the potential for public investment to create jobs, enhancing the financial sector, like encouraging Shabelle Bank, and modernizing credit service to make it more accessible and fairly provided. The regional government should also follow up with the government and private banks operating in the region to see how active they are in giving credit services to urban youth in the region.

Access to information for vacancies and time applied for were found to be highly significant determinants of urban youth unemployment in the study area. Urban youth who had access to information about jobs and applied more time for open vacancies were less likely to be unemployed. In order to help urban youth in job searching, regional government and local city administrations should make job postings available to everyone and provide access to job vacancy information. Additionally, in terms of providing employability training, public funding for apprenticeship and internship programs, and on-the-job training subsidies, regional governments should adopt clear policies and strategies.

Living in Jigjiga, the region's capital city, has a significant association with the likelihood of youth unemployment, which may be due to the significantly larger number of youths who migrated to the city for employment. Another probable explanation is that Jigjiga, the capital city of the region, has an increasing youth population and low employment opportunities in both the government and private sectors, which is putting greater stress on the labor force. Therefore, this study recommends that the regional government should develop a clear and adoptive market policy for urban areas of the region, specifically Jigjiga City, which is facing great challenges related to youth unemployment. Youth migration to Jigjiga also needs separate strategies to manage the high movement of youth from other urban or rural areas to Jigjiga to find employment opportunities.

Finally, local city administrations, in support of regional and federal governments, should take responsibility for locally managing youth unemployment and mobility. This can happen by giving youth an equal chance to apply for jobs based on their qualifications. And giving short-term training and life skills to uneducated youth who have migrated from rural areas to their respective cities.

Author Contributions

Abduselam Abdulahi Mohamed and Mohd Asif Shah have equally contributed to conceptualization, literature analysis, review drafting, supervising and analyzing data.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All the authors confirm the final authorship for this manuscript. We acknowledge that all listed authors have made a significant scientific contribution to the research in the manuscript, approved its claims, and agreed to be an author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to this article's content.

References

- Abera, Asalfew. Demographic and Socio-Economic Determinants of Youth Unemployment in Debere Birhan Town, North Showa Administrative Zone, Amhara National Regional State. Diss. Addis Ababa University, 2011.

- Ahemed Teyib (2020), “Determinants of Youth Unemployment; the case of Adama”. Master's Thesis. University of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Alhawarin, Ibrahim M., and Fuad M. Kreishan. "An analysis of long-term unemployment (LTU) in Jordan’s labor market." European journal of social sciences 15.1 (2010): 56-65.

- Allen, Cameron, et al. "A review of scientific advancements in datasets derived from big data for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals." Sustainability Science 16.5 (2021): 1701-1716. [CrossRef]

- Asmare, Yohannes, and Missaye Mulatie. "A tale of youth graduates’ unemployment." Global Journal of Human Social Science (A) 14.4 (2014): 46-51.

- Berhanu et.al. "Characteristics and determinants of youth unemployment, underemployment and inadequate employment in Ethiopia." Employment Strategy Papers (2005).

- Bhorat, Haroon. "Unemployment in South Africa: descriptors and determinants." commission on growth and development, World Bank, Washington DC (2007): 16-22.

- Cattaneo, Cristina. "The determinants of actual migration and the role of wages and unemployment in Albania: an empirical analysis." (2004).

- CSA (2020), Urban Employment /Unemployment Survey. FDRE, Central Statistics Authority. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Curtain, Richard. "Youth and employment: A public policy perspective." Development Bulletin 55.1 (2001): 7-11.

- Dejene et al. "Determinants of Youth Unemployment: The Case of Ambo Town, Ethiopia." International Journal of Economics and Business Management 2.2 (2016): 162-169.

- Duguma, Amenu Leta, and Fufa Tesfaye Tolcha. "Determinants of urban youth unemployment: the case of Guder town, Western Shoa zone, Ethiopia." International Journal of Research-Granthaalayah 7.8 (2019): 318-327.

- Gebeyaw, Tegegn. "Socio-demographic determinants of urban unemployment: the case of Addis Ababa." Ethiopian Journal of Development Research 33.2 (2011): 79-124. [CrossRef]

- Gebeyaw, Tegegn. "Socio-demographic determinants of urban unemployment: the case of Addis Ababa." Ethiopian Journal of Development Research 33.2 (2011): 79-124. [CrossRef]

- Haile, Getinet Astatike. "The incidence of youth unemployment in urban Ethiopia." 2nd EAF International Symposium on Contemporary Development Issues in Ethiopia (2003).

- ILO (2012), World Employment [Report]. Employment Productivity and Poverty Reduction.

- ILO (2015), Labour: World youth Employment outlook, Geneva.

- ILO (2018), Decent work and the Sustainable Development Goals, Geneva.

- ILO (2020), Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: A generation at risk / International Labour Office - Geneva.

- Kassa, Abebe Fikre. "Unemployment in Urban Ethiopia: Determinants and Impact on household welfare." Ethiopian Journal of Economics 21.2 (2012): 127-157.

- Kibru, Martha. "Employment challenges in Ethiopia." Addis Ababa University (2012).

- Labor Force Survey, Statistical Report on the 2013 National Labour Force Survey, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2013).

- Maqbool, Muhammad Shahid, et al. "Determinants of unemployment: Empirical evidences from Pakistan." Pakistan Economic and Social Review (2013): 191-208.

- MoYSC, The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia National Youth Policy, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2004).

- Mroz, Thomas A., and Timothy H. Savage. "The long-term effects of youth unemployment." Journal of Human Resources 41.2 (2006): 259-293. [CrossRef]

- Nganwa, Peace, Deribe Assefa, and Paul Mbaka. "The nature and determinants of urban youth unemployment in Ethiopia." Nature 5.3 (2015): 197-203.

- Nunnally, Jum C. "An overview of psychological measurement." Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders (1978): 97-146.

- Shah, Mohd Asif, and A. Anbuvel. "Cropping pattern change in Jammu & Kashmir-A case study of district kulgam." Golden Research Thoughts (GRT-IMRJ) 6.6 (2016): 1-13.

- Shah, Mohd Asif. "Determinants Crop Diversification in Jammu & Kashmir-A Case Study of District Kulgam." Indian Streams Research Journal (ISJR-IMRJ) 6.10 (2016): 70-77.

- Shah, Mohd Asif. "Socio-Economic Impacts of Apple Production in Kulgam District of Jammu and Kashmir." EPRA International Journal of Research & Development Journal (IJRD) 2.11 (2017): 67-73.

- Shina, Esay Solomon. "Determinants of Youth Unemployment: The Case of Hawassa City." IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) 22.4 (2020): 01-07.

- Shumet, G. "A Glimpse of Urban Youth Unemployment in Ethiopia." Ethiopian Journal of Development Research 33.2 (2011).

- Tegegne, Tsegaw Kebede. "Socioeconomic Determinants of Youth Unemployment in Ethiopia, the Case of Wolaita Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia." Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 10.23 (2019): 46-53.

- Tu, Yan, Jian Chu, and Mohd Asif Shah. "Industrial Demand and Innovation: An Application of Binomial Regression Model to Project Statistics of NSFC of China." Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022 (2022). [CrossRef]

- UN, World Youth Report: The Global Situation of Young People. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York (2003).

Table 1.

Summary table about employment status of sample respondents.

Table 1.

Summary table about employment status of sample respondents.

| Are you currently employed? (N=385) |

|---|

| |

Freq. |

Percent |

Cum. |

| Employed |

144 |

37.40 |

62.60 |

| Unemployed |

241 |

62.60 |

100.00 |

| Total |

385 |

100 |

|

Table 2.

Summary statistics and mean difference t-test for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Summary statistics and mean difference t-test for continuous variables.

| Variable |

Employed |

Unemployed |

|

| |

Unit |

Mean |

Std. Err. |

Std. Dev. |

Mean |

Std. Err. |

Std. Dev. |

t-value |

p-value |

| Age |

year |

25 |

0.35 |

4.22 |

23 |

0.241 |

3.73 |

-3.12 |

0.02** |

| Work exp. |

year |

4.94 |

0.21 |

2.56 |

1.099 |

0.044 |

0.69 |

-22.03 |

0.00*** |

| Time applied for job |

number |

6 |

0.22 |

2.70 |

2.701 |

0.121 |

1.88 |

-15.92 |

0.00*** |

| Educ. level |

Sch. year |

13.92 |

0.27 |

3.24 |

8.278 |

0.303 |

4.70 |

-12.70 |

0.00*** |

| HH Income (Monthly) |

ETB |

8209.23 |

509.88 |

6118.54 |

5835.35 |

491.462 |

7629.55 |

-3.17 |

0.02** |

| Family size |

number |

2.46 |

0.11 |

1.33 |

2.45 |

0.068 |

1.06 |

-0.07 |

0.95 NS |

Table 3.

Summary statistics and proportional differences chi2-test for categorical variables.

Table 3.

Summary statistics and proportional differences chi2-test for categorical variables.

| Variable |

Category |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Total |

ꭓ2 |

p-value |

| N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

| Sex |

Male |

119 |

82.64 |

121 |

50.21 |

240 |

62.34 |

40.38 |

0.00*** |

| Female |

25 |

17.36 |

120 |

49.79 |

145 |

37.66 |

| Access to credit |

Yes |

139 |

96.53 |

35 |

14.52 |

174 |

45.19 |

244.73 |

0.00*** |

| No |

5 |

3.47 |

206 |

85.48 |

211 |

54.81 |

| Access to Inform |

Yes |

115 |

79.86 |

50 |

20.75 |

165 |

42.86 |

128.62 |

0.00*** |

| No |

29 |

20.14 |

191 |

79.25 |

220 |

57.14 |

| Active job seeker |

Yes |

139 |

96.53 |

91 |

37.76 |

230 |

59.74 |

129.44 |

0.01*** |

| No |

5 |

3.47 |

150 |

62.24 |

155 |

40.26 |

| Social network |

Yes |

134 |

93.06 |

102 |

42.32 |

236 |

61.31 |

97.79 |

0.00*** |

| No |

10 |

6.94 |

139 |

57.68 |

149 |

38.75 |

| Job preference |

Self-employment |

87 |

60.4 |

44 |

18.26 |

131 |

34.03 |

90.12 |

0.00*** |

| Paid employment |

38 |

26.39 |

182 |

75.52 |

220 |

57.14 |

| Any job available |

19 |

13.19 |

15 |

6.22 |

34 |

8.83 |

| Town |

Living in Jigjiga |

27 |

18.75 |

63 |

26.14 |

90 |

23.38 |

19.71 |

0.02*** |

| Living in Dagahbour |

21 |

14.58 |

49 |

20.33 |

70 |

18.18 |

| Living in Kebridahar |

35 |

24.31 |

40 |

16.6 |

75 |

19.48 |

| Living in Gode |

43 |

29.86 |

37 |

15.35 |

80 |

20.78 |

| Living in Dollo Ado |

18 |

12.50 |

52 |

21.58 |

70 |

18.18 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).